9 minute read

The Renaissance in Northern Italy

Rooms

1

Advertisement

2

The Advent of Reality

Light and Colour in Venice

Northern Italy and its flourishing urban centres were the scene of a splendid period in the arts during the fifteenth century, marked by the slow decline of Late Gothic taste intertwined with the gradual establishment of the Renaissance. An emblematic figure in this transitional phase was Pisanello, who combined the elegance and chivalrous ideals typical of the world of the medieval courts with the first fervour of humanism.

The throbbing heart of the Renaissance renewal was Padua. The presence in the city of the Florentine sculptor Donatello between 1443 and 1453 prompted artists to engage more directly with the Tuscan innovations: the perspectival construction of space, the study of classical models and the possibility of faithfully representing human life and emotions.

Padua witnessed the growth and emergence of Andrea Mantegna, Northern Italy’s leading Renaissance figure. His severe, solemn style, which drew heavily on ancient art, represented an almost incomparable benchmark for artists of his generation, often striving to combine aspects of the fable-like narration of the court world with a more confident spatial rendering of figures and architecture.

Instead, in Venice, the second half of the fifteenth century was marked by the emergence of Giovanni Bellini. His painting was based on the skilful use of light and colour, which gave his compositions a sweetness and verve that had never been seen before. But first and foremost, he was the first great interpreter of the human figure in a natural landscape setting.

Also working in the city, besides Bellini, were masters with different approaches, strongly influenced by the work of Antonello da Messina, the Sicilian artist who sojourned in Venice around 1475. Standing out from among the others was Vittore Carpaccio, who specialized in producing large narrative canvases for the lay confraternities known in the lagoon as scuole or “schools”.

1441-1444 (?) tempera on panel 29 × 19.5 cm Giovanni Morelli Collection, 1891

Pisa, Verona or San Vito (?) c. 1395 - Naples c. 1455

Pisanello (Antonio Pisano) Portrait of Leonello d’Este

Pisanello was the last exponent of the highly elegant court culture known by the name of International or Late Gothic. An itinerant artist working between Verona and Venice, Mantua and Milan, Rome and Naples, he was for a long time in the service of Leonello d’Este, the refined Marquis of Ferrara. The Carrara portrait was probably executed in a celebrated painting competition in 1441, which saw Pisanello pitted against Jacopo Bellini. The set of the profile takes up the model of ancient medals, but the distinctive features of the face are carefully investigated. Leonello’s thick head of hair, the brocade of his attire and the herbarium flowers of the rose garden are meticulously described with the soft, molten brushstrokes typical of the artist’s refined and profane taste.

c. 1440 - 1445 tempera and gold on panel 58.4 × 32.7 cm 58.1 × 34 cm gift of Antonietta Noli Marenzi, 1901

documented from 1441 - Padua before 1450

Giovanni d’Alemagna Saint Apollonia with her Teeth Torn Out Saint Apollonia Blinded

Giovanni d’Alemagna was an artist of German origin who worked between Venice and Padua in the 1440s. Together with his brother-in-law Antonio Vivarini, with whom he often collaborated, he was one of the most lively interpreters of the period of transition between the Middle Ages and Renaissance in the Veneto. The Accademia Carrara panels are part of a larger whole whose original appearance is unknown, but which included two other small panels depicting scenes from the life of Saint Apollonia, held in the Museo Civico di Bassano del Grappa and the National Gallery of Washington. The fable-like narrative tone, the profane taste in clothes and headdress, and the freely imaginative reinvention of the classical repertoire in the architecture make the scenes from the life of Saint Apollonia one of the most fascinating examples of the intermingling between the Gothic tradition and new Renaissance impulses in painting.

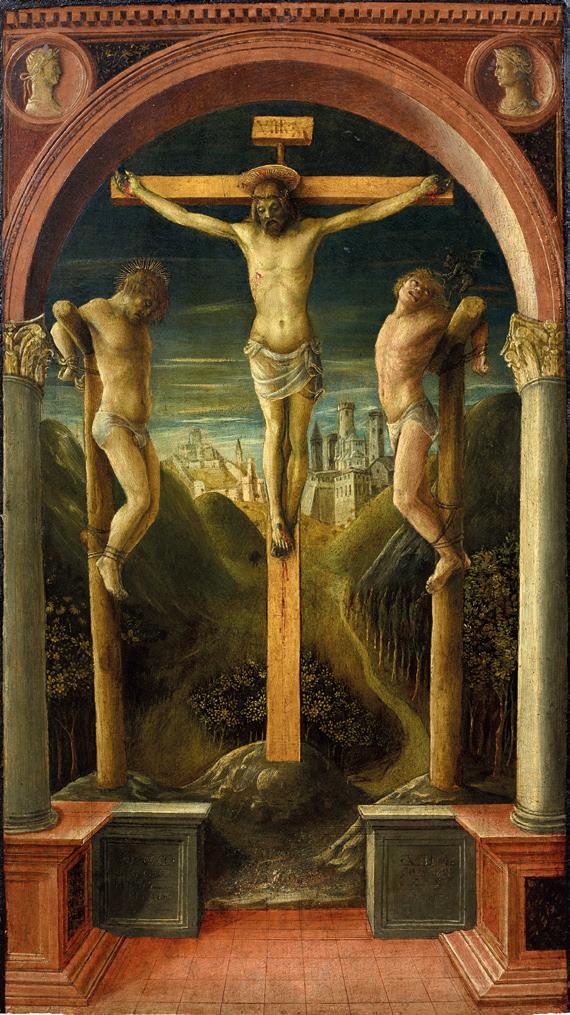

6th April 1450 or April 1456 tempera on panel 69 × 39 cm Giacomo Carrara Collection, 1796

Bagnolo Mella, Brescia, c. 1427 - Brescia 1515/1516

Vincenzo Foppa Three Crucifixes

The painting is one of Foppa’s first works, executed when the young artist was trying to combine the enchanted world of Gentile da Fabriano with the reenactment of antiquity by Jacopo Bellini and the intense expressiveness of Donatello’s sculpture, which he had encountered in Padua. It is an immensely powerful devotional image, presenting the worshipper with the solitary agony of Christ, accompanied by the two thieves but without the comfort offered by the customary figures of Mary, the Magdalene and Saint John. The light of sunset falls upon the bodies and the harsh landscape of forests and turreted cities. The antique triumphal arch leads the viewer’s gaze into the scene and at the same time softens the emotional involvement, thus favouring a more cerebral approach to the meaning of the Passion.

c. 1485 - 1490 tempera and gold on canvas 45.5 × 35.5 cm gift of Carlo Marenzi, 1851

Isola di Carturo, Padua, 1431 - Mantua 1506

Andrea Mantegna Madonna and Child

A promising young artist in the Padua of Donatello and Squarcione, Andrea Mantegna soon became one of the most celebrated painters of his age, a pre-eminence sealed when he moved definitively to the Gonzaga court in Mantua. The Carrara Madonna and Child dates to the middle of the artist’s career, and was produced after his works for the Camera degli Sposi. This austere yet moving image of motherhood foretells Christ’s future sacrifice on the Cross, alluded to by the red coral bracelet worn by the Child and the Virgin’s distant gaze, tinged with melancholy. The work’s muted colours are the result of Mantegna’s use of tempera, his favourite medium, which he applied in thin layers on a very fine linen canvas.

c. 1472 - 1473 tempera and oil on panel 34 × 27.5 cm Guglielmo Lochis Collection, 1866

Venice c. 1430 - 1516

Giovanni Bellini (?) Portrait of a Young Man

The portrait is set out as a classical bust and immediately recalls the stern models of Andrea Mantegna, who had married Bellini’s sister Nicolosia. The solid arrangement of volumes and the intense gaze directed at the viewer by the young man attest to an interest in the portraits of Antonello da Messina, active in Venice around 1475. A fragmentary inscription on the rear (“IACOBUS D”), initially interpreted as a reference to the work’s author, is instead the only faint clue to the identity of the painting’s mysterious subject.

1480 oil on panel 64.6 × 45 cm Giacomo Carrara Collection, 1796

Messina c. 1456 - Venice (?) before 1488

Jacopo di Antonello (Jacobello di Antonello) Madonna and Child

The painting is the only signed and dated work of Antonello da Messina’s son, and also the only one that can be attributed with certainty. Upon his father’s death in February 1479, Jacobello inherited the workshop and undertook to complete the unfinished works, which probably included the Carrara Madonna and Child. In fact, in the powerfully three-dimensional construction of the faces, in the virtuoso glimpse of the hand holding the cup of transparent glass, and, finally, in the landscape, described with a meticulousness reminiscent of Flemish painting, Jacobello drew on some of the ideas of his father, who, as the scroll resting on the parapet affirms, was “not human”, in other words, truly incomparable.

c. 1487 tempera and oil on panel 84.6 × 65 cm Giovanni Morelli Collection, 1891

Venice c. 1430 - 1516

Giovanni Bellini Madonna and Child (Alzano Madonna)

This painting is one of the mature masterpieces of Giovanni Bellini, the artist who left an indelible mark on Venetian painting in the second half of the fifteenth century. The image is distinguished by the relationship between the monumental group of the Madonna and Child and the clear landscape stretching out behind them, in which the hand of another painter was suspected. Mary is clasping the Child in an affectionate embrace that is a kind of heartfelt prayer, and her absorbed gaze reveals that she is aware of her son’s future sacrifice on the Cross. Sitting on the marble parapet is a pear, which, by virtue of its sweetness, is often associated in Christian symbology with the figures of the Madonna and of Jesus as a symbol of the love uniting them.

c. 1502 - 1504 oil on canvas 128.5 × 127.5 cm Guglielmo Lochis Collection, 1866

Venice c. 1465 - 1525/1526

Vittore Carpaccio and workshop Birth of Mary

Carpaccio was the first great exponent of the city view, but also a marvellous painter of interiors, as shown by this painting, in which time seems to stand still. The canvas is part of a series of scenes from the life of Mary produced for the Scuola degli Albanesi in Venice. The Virgin’s mother, St. Anne, is resting after childbirth, assisted by servants and a midwife, who is preparing a bath for the new-born child. Anne’s elderly husband Joachim observes the scene from a slight distance. The story is enriched with apparently secondary but highly symbolic details: the two rabbits nibbling at a cabbage leaf allude to Mary’s virginity; the Hebrew words “Holy Holy Holy in Heaven blessed is He who comes in the Name of the Lord” ties in with the name of Christ engraved, again in Hebrew characters, on the door jamb.

1505 - 1510 tempera and oil on canvas 66 × 58.5 cm Giovanni Morelli Collection, 1891

Vicenza (?) c. 1449 - Vicenza 1523

Bartolomeo Montagna (Bartolomeo Cincani) Saint Jerome in Bethlehem

Trained in Vicenza and Venice, and influenced by the painting of Giovanni Bellini and Antonello da Messina, Montagna was active prevalently in the inland areas of the Veneto. Coexisting in his work is a fondness for inserting the figure into the landscape, typical of the Venetian tradition, and an interest in the Lombard culture of perspective. Saint Jerome is a fully mature painting showing the artist’s moving efforts to keep up with the innovations of the age without foregoing the pleasure of a detailed narrative. The author of the Latin version of the Bible is not depicted as a religious recluse, or robed in the red attire of a cardinal, but dressed as an abbot and accompanied by the customary lion. Visible behind him is the monastery of Bethlehem, to which the elderly theologian retreated. Men and animals coexist peacefully, intent on their daily tasks, while in the distance the mountains and sky are tinged by the early evening light. The image celebrates the life of the cloister, of which Jerome is seen as a perfect emblem.