HISTORIES

GIOVANNI BONELLO

First published by Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti and Kite Group Ltd, 2024

Editorial Copyright © Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti, 2024

Literary Copyright © Giovanni Bonello, 2024

Photographic Copyright © Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti, photographers, and institutions, 2024

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without prior conditions, including this condition, being imposed on any subsequent publisher.

This new series is being generously supported by the Francis Miller Memorial Fund

Creative Director

Michael Lowell

Design and Layout

Lisa Attard

Editor Giulia Privitelli

Produced by Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti

ISBN 978-9918-23-141-6

Printed in Malta Progress Press Co. Ltd in partnership with

HISTORIES

1

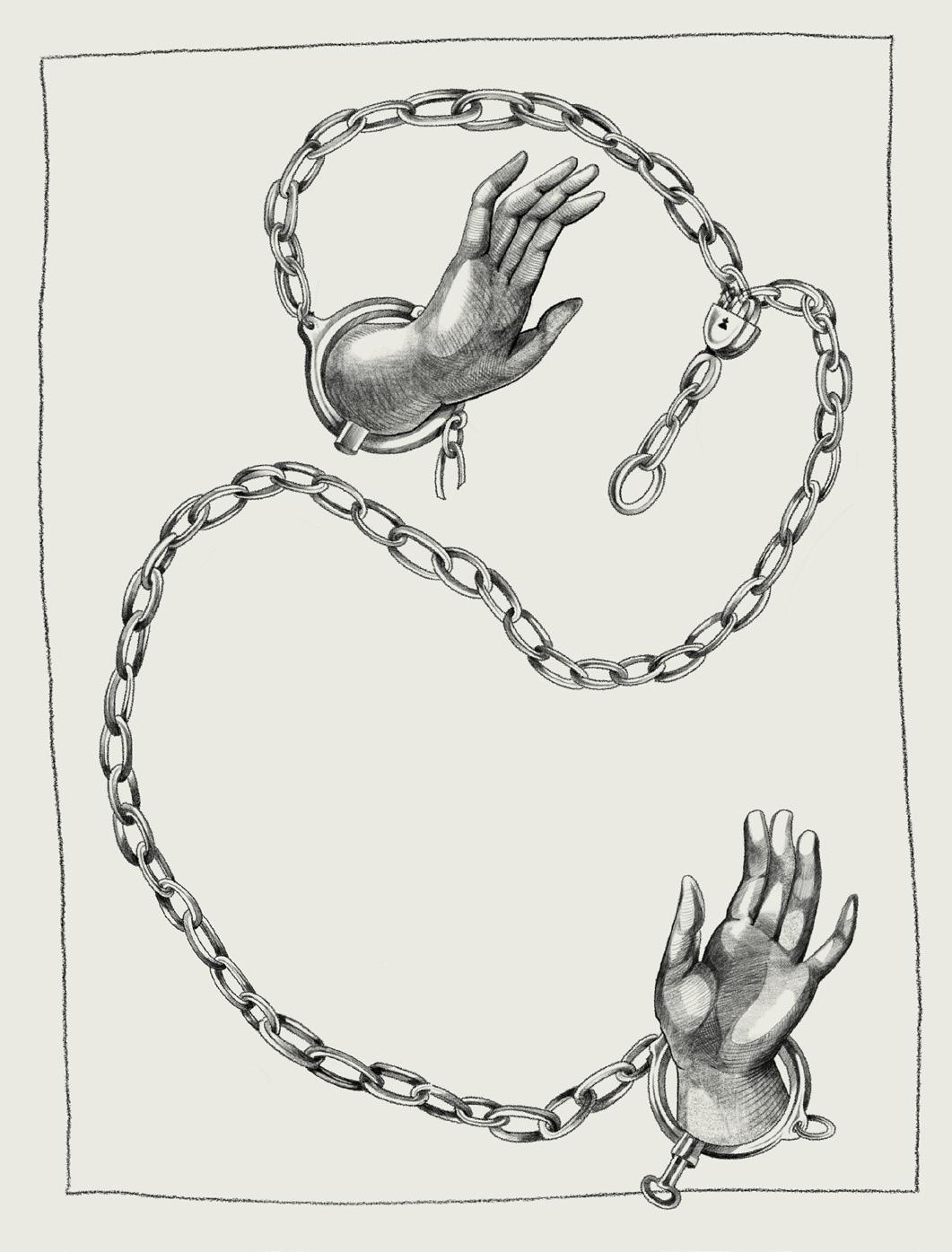

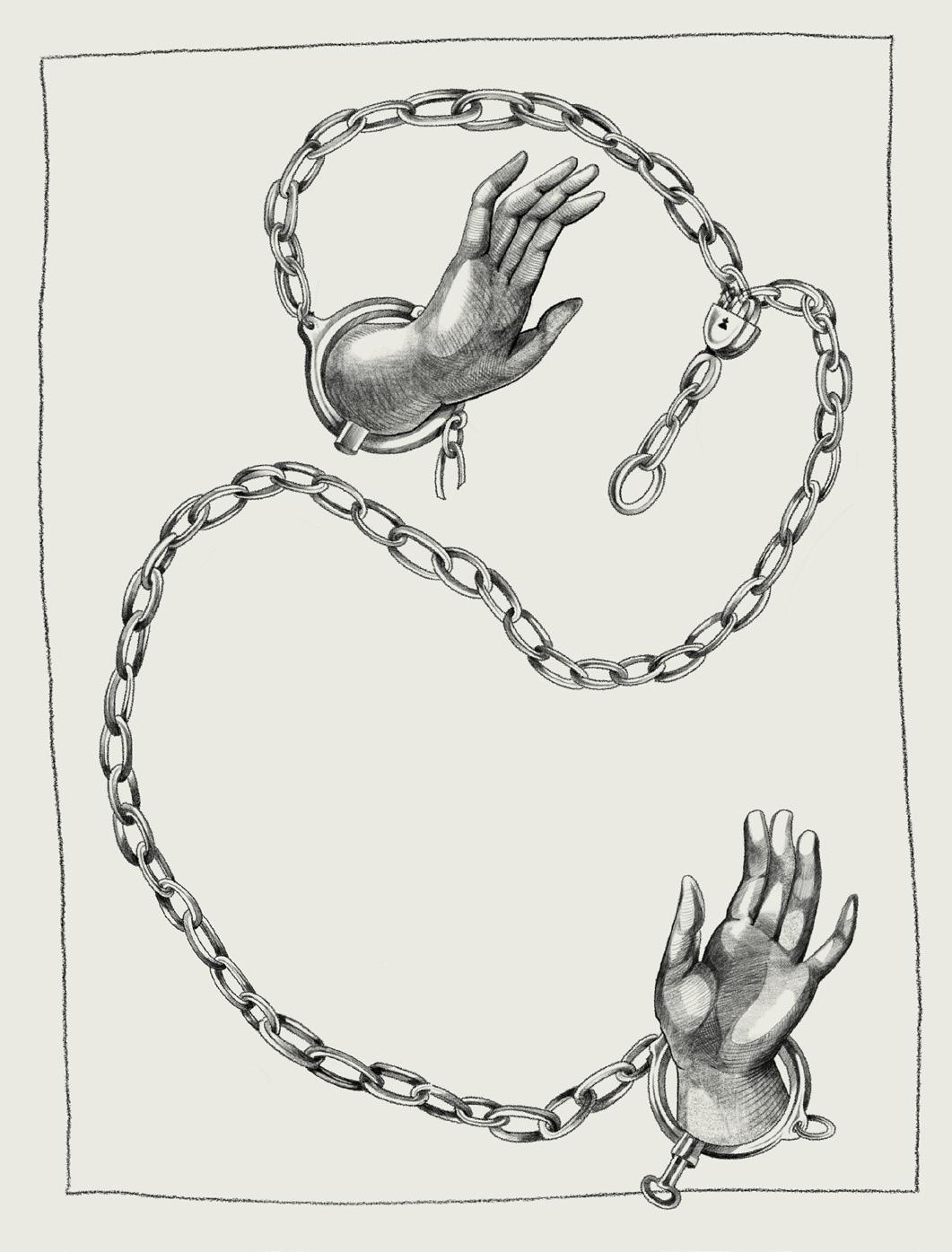

The title page illustration, by Rebecca Bonaci, features uniquely designed interrelated motifs that reflect the themes of each volume of this new series, More Histories.

Just over ten years ago, in 2013, Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti published the last volume of Histories of Malta, a twelve-part series which overflows from the narrowest and darkest corners into the most iconic and unforgettable aspects of the Maltese Islands’ history and heritage. Archival and visual records, literature, artefacts and artworks, hearsay, and local knowledge, passed from generation to generation to the perked ears and readied pen of the author, Giovanni Bonello. They fed and shaped that microcosmic narrative, inviting the reader down foreboding corridors and exciting and unexpected turns into, not quite the heart, but the outskirts of Malta’s labyrinthine history. There are many leading actors, both heroes and villians, in these stories, but ultimately it is the one holding the pen who also wields the sword that will deliver the final blow. With this new series, it is as though Bonello feels that time has not yet come; there is still more to discover about the monster lurking within before we even dare face it. Some steps ought to be retraced, stories revisited, and others viewed from different angles.

To help us, as if equipping us with Ariadne’s thread, stories previously published and scattered among several issues of local newspapers and periodicals have been collected, many widely reworked, and presented here thematically. Though this new series will not be as extensive as its forerunner, its content is nonetheless a potent mix of humanity, crime and creativity, and illustrates some of the most haunting (and hopeful?) questions concerning the human condition: Why do humans err? Who or what can be blamed for such error? How can it be dealt with, transformed, or even, remembered? None of these questions are addressed in a direct way, but read closely and you might catch them watching you, perhaps quietly gesticulating the way onwards. Remember where you are in this labyrinth: the periphery. But, even if against all reason, it is the heart, the centre of all things, that we desire most to reach. And so, we are compelled to thread on, guided by the author’s hand, and with uncertainty accompanied hand in hand with our curiosity.

Faltering, with bowed heads, our altered parents Slowly descended from their holy hill, All their good fortune left behind and done with, Out through the one-way pass Into the dangerous world, these strange countries.

‘All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.’ Sounds familiar? This is, of course, Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), published just over 350 years after the earliest story recounted in this anthology in which such human dignity, such reason, such conscience, and such brotherhood were but forgettable and difficult concepts yet to be set in stone. That is, if we were to regard the infamous story of the new, then broken, then renewed stone tablets recounted in the Old Testament as just that: an old testament, an ageing witness to truths revealed, with an agenda to enslave those poor and believing souls for the sake of freedom, equality, dignity…

But what freedom, what equality, what dignity in the fifteenth or sixteenth or nineteenth century? Rights were for those who could pay to have them unearthed from their sleeping chamber buried deep beneath duty and responsibility, and often deemed non-existent if you simply had the misfortune of being born where and as you are. Meanwhile, dignity, like those so-called rights, was a title or a concession to be bestowed. And equality? A matter of lineage, luck, and melanin. Human beings? In most cases, as you will soon have the pleasure to discover, was

a condition some felt the need to justify or write off as simply being human. And that would include anything between love and pride, despair and hope, success and failure, rising and falling.

In this anthology there is much to be said about ‘falling’. What is it that drives a human being over the edge, to think the unthinkable, to carry out the undoable, to record the unsayable? There is not much that the records can, in fact, reveal; much is left up to your own discernment, dear reader. But whatever could be patched up together in some form of coherent narrative, Giovanni Bonello did, with a distinctive wit that makes his storytelling light, shocking, forgiving, and hilarious, all at the same time. And who better qualified, too? With at least twelve years of experience as a Judge at the European Court of Human Rights, and around 170 defended human rights lawsuits in domestic and international courts under his belt, who could have a better vantage point to review and retell such episodes which, more often than not, are relegated to the margins of our history books or, a fate worse still, reduced to a footnote?

Here, then, is the result, albeit a selection of it, with slightly different versions of these anecdotes, perhaps, being told elsewhere. Thread and read with care, mindful that these stories are just a part, a dark mirror reflecting what might have happened. Observe and consider all you can but please, I beg, leave judgement aside. For there is, indeed, something that unites and ‘humanises’ all human beings through their waking, breathing lives: the predisposition to err, even if with all good intentions. Falling is as much of mankind’s journey on earth and is, if for no other reason, worth recalling.

Giulia Privitelli Editor

A 1588 Homicide by a Knight of Malta

Lawyers and Lawyering in Malta before 1600

A 1636 Murder in Birgu … and its Fall-Out

Mischievous Books in the Times of the Order

Thefts from Churches in Malta

Tragic Tales of Slaves in Malta

Caterina Scappi Revisited

The 1832 Beheading of a Young Woman in Senglea

The Tragic Prince of Abyssinia in Malta

Mankind in the Red-Light District

(More of) Mankind in the Red-Light District

Counting on Dishonour among Thieves during Early British Rule

How Early British Rule Affected the Legal Profession in Malta

‘For what difference is there between provoker and provoked, except that the former is detected as prior in evil-doing, but the latter as posterior?’

The luxuriant criminal energies prevalent in Malta during the first century of the rule by the Order of St John have not been properly studied so far. Many reasons account for this information blackout—mostly the poor documentation available. The Order of Malta generally suffered from compulsive record-keeping manias during its stay on the islands, and most of its written data have been preserved. Not so those of the two major systems of criminal justice: the one of the Knights for the knights, and that of the Prince for the rest of the population.

These were two completely autonomous and independent organisations— the Castellania criminal justice for the people, while the Sguardio system regulated exclusively crimes committed by knights or those committed against knights. The first was left almost entirely in the hands of the natives: Maltese judges, lawyers, prosecutors, registrars, jailers, and executioners. The second remained the jealously guarded preserve of the Order. In 1781, the internationally famed jurist Giandonato Rogadeo, invited to Malta to reform the laws and the court system, confessed he had never seen anything as appallingly corrupt and inept as the Maltese administering justice.

The written records of the Order’s criminal trials have disappeared. Virtually nothing is left of the thousands of fat files that documented in clinical, but often gory, detail the reports of criminal offences committed by knights or against knights, the investigations, the evidence, the statements of witnesses, the pleadings by the lawyers, the final judgements. Nobody seems to know when or why this mountain of history was wasted, or by who, when most of the other records were, more or less conscientiously, preserved. The fact remains that today we can only attempt to reconstruct the criminal scene through the flimsiest of evidence, the most evanescent of documentation.

All that remains, and because they were recorded in a different set of volumes, are the skeletal minutes of final deliberations by the adjudicating council. The precious Libri Conciliarum, which register the decisions of the Council of the Knights, have thankfully survived. But these only contain the skimpiest and most economical annotations imaginable: today Fra XY was condemned to prison for

theft; today Fra AB was found guilty of the homicide of CD and sent to the guva. In the otherwise bleak circumstances, thanks providence for little mercies. These records are the equivalent of what we still today refer to in old Italian legal jargon as prime note. Nothing else. The full criminal files have vanished.

The Council of the Order met regularly and frequently in the Grand Master’s Palace in Valletta, and generally it had a very loaded agenda to go through—administrative and diplomatic matters, promotions, supplies and services, commissioning and examination of reports—and criminal proceedings. Strangely and quite unusually, for the meeting of 12 July 1588, the Council placed only one item on its agenda: the trial of the knight Fra Andrea de Chiambaly, accused of homicide. Usually, these criminal trials did not take up a lot of the time of the Grand Master’s counsellors: they examined the report drawn up by the two commissioners delegated to compile the evidence and draw their conclusions, and then they took a secret vote on its contents—guilty or not guilty (called lo scrutinio delle palle). In the former case, the Grand Master in Council also deliberated on the punishment to be awarded.

Fra Andrea’s real family name was Ciambanin, not Chiambaly, but scribes, in those days, jotted down proper names quite approximately, not according to any strict protocol but just as they believed they sounded phonetically. The fact that the clerk recorded him as ‘de Chiambaly’ possibly indicates that the delinquent was believed to be of French origin.

Fra Andrea stood charged with the wilful homicide of a Maltese subject, Nicola Borg, known as Cola. The Council found him guilty and condemned him to a five-year term of imprisonment. Quite likely, the Counsellors could not reach a unanimous verdict as the minutes would otherwise have recorded nemine discrepante—no one disagreeing. That is all the surviving records state—the name of the accused, that of the victim, the nature of the crime charged, and the sentence passed. Nothing about the date and the circumstance of the crime, its motive, in what way it was carried out, the weapons used, the defence of the accused, the details of the penalty.1

This bleak dearth of information has, in this particular instance, been somehow relieved by a fortuitous find in the Notarial Archives. Among the thousands of loose papers, unclassified documents, and what-is-this-doing-here bric-a-brac, the staff working there under Dr Joan Abela spotted a cinquecento petition connected with a murder investigation, which she kindly drew my attention to.

I instantly recognised this was linked to the Cola Borg homicide. It is the original of a petition filed by Pietro Ciambanin, the grieved father of the accused knight, to Grand Master Hughes de Loubenx de Verdalle. The supplica does not have a date, but the deliberations which follow it on 20 January 1588, allow us to establish the temporal sequence. The petitioner wrote quite legibly, though the subsequent annotations by the Grand Master’s bureaucrats prove more difficult to decipher.

The father of the knight accused of murder, himself a member of the lower ranks of the Order (a Fra donato, not professed with solemn vows, and only authorised to wear a six-pointed cross, not the full eight-pointed one) wanted the Grand Master to be aware that ‘the wife, the mother, sons and relatives of [the late] Cola Borg, not satisfied with having accused and proceeded with the alleged homicide of the said Cola, against Fra Andrea Ciambanin, servant at arms, his son, who, in fact had been provoked, insulted and ill-treated (maltrattato) suffering wounds; but to inflict further pain on the petitioner’, pressed their criminal charges not only in front of the Grand Master’s tribunal in the Castellania, but also in front of the tribunal of the Order of St John, to show how he has been unjustly accused and prove his innocence. The father humbly petitioned the Grand Master to instruct two impartial (non suspetti) knight Commissioners to compile the evidence to establish the true facts of the case and refer to the Council in order that justice be done.

The Ciambanins had already left faint, unremarkable footprints of their presence in Malta. In 1575, Pirro Ciambanin had put his name down as a founder of the Corpus Christi confraternity in the parish church of Porto Salvo, St Dominic, Valletta.2 Pirro, as a Christian name, is an old Italianate variant of Piero, Pietro.

Parts of the rest of the texts following the supplica appear rather illegible to me, both because the ink has faded and because it has seeped onto the other face of the paper, interfering with the writing’s legibility. The Council appointed the two investigating Commissioners, the senior knights Commendatore Nicola Sciortino from Noto, who had joined the Order immediately after the Great Siege, and Fra Antonio Caccialepre, who I have been unable to trace. The only Antonio Caccialepre I know of was one of the two brothers of Greek descent who established in Malta the devotion of the Risen Christ by erecting the chapel of the Annunciation, Rabat, and endowing it with an image of the Resurrection. But this Antonio does not seem to have been a Knight of Malta.3 Were two Antonio Caccialepre concurrently in Malta when the homicide took place? Possibly but unlikely. These notes also mention the relatives of the murder victim: Pauluccia his widow, and Mario and Martino Borg his sons.

The name of the priest Giuseppe Famigliomeno appears in the records too, though the poor condition of the petition does not make it easy to establish why.4 Quite possibly, this document includes his name as the Council had, in 1587, appointed him acting Vice-Chancellor of the Order during the absence in Rome of the incumbent Vice-Chancellor, Fra Didaco de Ovando.5

Fr Famigliomeno happened to find himself at the centre of another unruly brawl at exactly the same time as the homicide of Cola Borg, though the two episodes do not seem to be connected. He got involved in an argument during which the young troublemaker Fra Cassano Bernizzone6 from Genova slapped him soundly across the face. After a full trial, Bernizzone first ended in jail, and later lost his seniority, and Fra Giulio Cesare Raspa from Vercelli was defrocked; the Council also expelled the nobleman de Gabot from the Order for having perjured himself when giving evidence at their trial.7

This was neither Bernizzone’s first nor his last brush with the criminal law. In 1587, the Council had tried him for wounding grievously Fra Filippo Cesarino ‘with copious shedding of blood’. Condemned to jail, he escaped and had to face a second trial for absconding from prison. Shortly later, the Council

charged him with the murder of Fra Giuseppe d’Aragon and, having served his sentence, he resolved his criminal record needed further embellishment and he added a duel against Fra Filippo la Surda.

Despite Bernizzone’s familiarity with the insides of prisons, the Grand Master selected him as special envoy with a delicate mission for the Pope and the King of Spain.8 And, to confirm his rather unsteady piety, in the 1590s he built from his own purse the chapel of Our Lady of Graces in the new church of Porto Salvo, St Dominic, Valletta, and also pledged to endow it with an artistic altarpiece. That he failed to maintain this last promise is quite beside the point.9

This supplica allows us to reconstruct some clues of how the trial proceeded: who the Commissioners investigating the crime were, the fact that the victim’s family took an active part in the prosecution, and what defence the accused pleaded: extreme provocation and self-defence. Still, plenty of questions remain unanswered. One is: why and how did this supplica find itself in the Notarial Archives when, apparently, it has no connection with anything notarial?

The usual penalty for wilful homicide committed by a knight was expulsion from the ranks of the Order, as this then enabled the culprit to be handed over to the lay criminal courts and condemned to death (the statutes and custom exempted those who were still knights from the death penalty). The fact that the Council only inflicted a five-year term of imprisonment on Fra Andrea Ciambanin confirms that his judges accepted his pleas of provocation and selfdefence in mitigation.

The year of the homicide, 1588, was not a particularly spectacular or turbulent one for Malta. Pope Sixtus V had promoted Grand Master Verdalle to the rank of Cardinal Deacon of the Holy Roman Church and he had been lavishly welcomed in Rome when he travelled there to receive the princely hat. Not everyone, however, approved of that promotion: Cardinal Ascanio Colonna openly slighted and ridiculed the new Cardinal Deacon during an official banquet given in Verdalle’s honour in the Pope’s city, because he made no secret of considering Verdalle unworthy of becoming a Cardinal.

On his return to Malta in 1588, the freshly promoted Cardinal Grand Master built Verdala Palace in the Boschetto, limits of Rabat, but he also needed to settle scores with Cardinal Colonna, whose coat of arms was an upright column. Verdalle’s escutcheon showed a wolf. A malicious sense of humour inspired his vendetta. He ordered that Palace Square be embellished with a column, on which a wolf squatted, defecating. Verdalle wanted his revenge on Cardinal Colonna to last through the centuries and in his will he even established a substantial legacy for the maintenance and repair of his wolf crapping on Colonna.10

We know that after the trial, the Ciambanins remained in Malta, occasionally aspiring to some degrees of fame or notoriety. An entry in the Udienze records of 1609 shows that a certain Signor Ciambanin had erected a building on his own land but had, no doubt absent-mindedly, nicked a large tract of public land, incorporating it stealthily in his property.11 In 1619, Caterina Ciambanin married Pietro Caxaro, descendant of the Cantilena poet. Pietro Ciambanin bought the vineyard ‘tas-Sinjur’ in St Julians, and in 1634 he petitioned the Grand Master to allow him to enlarge it by encroaching on public land.12 Trophimo Deodato Ciambanin (1631–1658), son of Pietro and Argenta, took holy orders. Though baptised in St Paul’s church, Valletta, he was buried in Porto Salvo, St Dominic’s, when he died only twenty-seven years old.13

In 1679, another Pietro Ciambanin (Pietro must have been a distinctive name in the Ciambanin family) married the noblewomen Agostina Perdicomati—a family related to the ancestors of the former Prime Minister of Malta Sir Gerald Strickland. One of their daughters, Maria Teresa Ciambanin, strayed from the straight and narrow. She became the long-term mistress of a leading knight of Malta, the Balì Louis-Alphonse de Lorraine-Armagnac. I dare anyone to find a more supremely rarefied lineage than that. The Lorraine-Armagnacs counted as one of the most aristocratic and well-connected families in Europe, related by marriage alliances to half the sovereigns of the continent.

Maria Teresa Ciambanin never married Louis-Alphonse, but she, rather carelessly, bore him at least three daughters, informally known as d’Armagnac.

The eldest, Anna d’Armagnac, married Gio Nicolὸ Baldacchino in 1715; the middle one, Teresa d’Armagnac, that same year married Francesco La Speranza, while Pietro Galea took the younger one, Giovanna Maria d’Armagnac, as his spouse the following year. Miss Ciambanin, with her three illustrious bâtardes, must have magnetised the combined frowns of the rest of the God-fearing Maltese community. The target of blithe and rather jealous gossip, no doubt.14

Though by nobility of birth Balì Louis-Alphonse Lorraine-Armagnac ranked among the highest possible dignitaries of the Order, he never seems to have distinguished himself in anything at all, good, bad or indifferent, except for his commitment to flouting his solemn vow of chastity and providing tangible evidence to anyone who doubted his dedication. He died in Malaga on his twentyninth birthday, on 24 August 1704. His father was the brother of Philippe de Lorraine-Armagnac, also a knight of Malta, but better known for his legendary beauty and for having been the lifelong gay lover of Philippe d’Orleans, the transvestite younger brother of Louis XIV, King of France.

Hints of Ciambanin DNA and of the dazzlingly blue blood of the Lorraine-Armagnacs must still lurk discreetly in the crannies of Maltese arteries and veins.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My heartfelt thanks to Dr Joan Abela who put me on the right track, to Maroma Camilleri, who just cannot help being helpful, and to Dr Theresa Vella who introduced me to the Udienze reference.

P.x Engraving after Cavalier d’Arpino showing knights imprisoned in the Castellania with the Conventual Church of St John the Baptist in the background, from Grand Master Verdalle’s Statuta Hospitalis Hierusalem, chapter 18 ‘De Prohibitionibus Et’ (Rome: Titi & Pauli de Dianis, 1588). (Courtesy of the National Library of Malta)

P.4 Supplica by Pietro Ciambanin, 1588, from the loose-leaf collection at the Notarial Archives in Valletta. (Courtesy of the Notarial Archives Foundation)

P.8 Engraving after Cavalier d’Arpino showing a criminal trial of a knight of Malta, from Grand Master Verdalle’s Statuta Hospitalis Hierusalem, chapter 7 ‘De Concilio et Iudiciis’ (Rome: Titi & Pauli de Dianis, 1588). (Courtesy of the National Library of Malta)

1 AOM 97, f. 139.

2 George Aquilina and Stanley Fiorini, Documentary Sources of Maltese History. Visita Apostolica Pietro Dusina, 1575, Part IV, No. 1 (Malta: Malta University Press, 2001), 16.

3 Mikiel Fsadni, Qlubija, Twegħir u Faraġ f’Sekli Mqallba (Malta: Pubblikazzjoni Dumnikana, 1997), 74.

4 NAV [Notarial Archives, Valletta], sixteenthcentury loose-leaf collection, 1588 supplica by Pietro Ciambanin.

5 AOM 97, f. 109v.

6 Also Bernissone.

7 AOM 97, ff. 127-128, 131v.

8 Giovanni Bonello, Histories of Malta, Vol. 10 (Malta: Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti, 2009), 54.

9 Mikiel Fsadni, Id-Dumnikani fil-Belt (Malta: Veritas Press, 1971), 24-25, 48-49.

10 Victor Mallia-Milanes, Descrittione di Malta. Anno 1716: A Venetian Account (Malta: Bugelli Publications, 1988), 103.

11 AOM 663, f. 126v. The text says Chamberlain, but the phonetic French pronunciation of Ciambanin would be Ciambanin.

12 AOM 1184, f. 91.

13 Vincent Borg, Melita Sacra, Vol. 3 (Malta, 2015), 273.

14 See, www.maltagenealogy.com—‘Ciambanin’.

‘Formerly we suffered from crimes; now we suffer from laws.’

Tacitus

Let’s face it: so far, we know virtually nothing about the origins of the legal profession in Malta or what it was like when the Order of St John of Jerusalem received the islands from the King of Sicily, the Emperor Charles V, in 1530. We take it for granted that lawyers were present and practised their profession on these islands. Yes, but who were they? Where did they study and graduate? How were they regulated? What was their career path?

Albert Ganado’s invaluable book—half biography of his father Judge Robert Ganado and half chronicle of the Maltese civil service from 1815 and of the legal profession from 1666—has fleshed out lists of lawyers who exercised their profession in Malta. The first name on these lists is that of Dr Gio Andrea Cangialanza, but he is only recorded as active as late as 1666.1 I sought to find out if I could push that date further back and fill in some gaps.

The vast Malta documentation of the Castellania Regia of the Court of Palermo, brilliantly and meticulously transcribed by Stanley Fiorini, repeatedly has mentions of advocates (jurisperitus, legum doctor, Doctor Utriusque Juris, IUD) present and working in Malta, many mentioned by name. These sources range all the way between 1259–1500. Many of these Doctors of Laws were obviously not Maltese, but (mostly Sicilian) lawyers who dealt with Maltese controversies in Sicily, or were specifically sent over to Malta to resolve complex legal issues. Most delegations from the Court of Sicily to Malta included advocates.

But some of those mentioned might perhaps have been Maltese, like Raimondo Implomaceri, legum doctori, appointed in 1409 to take over all civil and criminal lawsuits in Malta and Gozo, and determine them without right of appeal, except directly to Queen Bianca of Sicily.2 Again, Leonardo Bartolo, legum doctorem, is tasked in 1434 with certifying the ability of Andrea de Beniamino from Gozo to exercise the profession of notary.3 In 1456, the Court of Palermo overrides the Maltese Universitas and appoints officials in Malta directly, among them Pietro di Modica, legum doctorem, as appeals judge, and Lanza Dasti, Nicola Raficano, and Nicola de Zarlo as judges of the civil court. Were these lawyers Maltese?4

There are two Doctors of Laws, Geraldo Aglata and Mariano Aglata, both chief notaries (protonotari), who appear repeatedly in the records, particularly in the examination and approval of Maltese and Gozitans to exercise the notarial profession, and other public offices, from 1462 to 1487. Were they established in Malta? Did the candidates travel to Sicily for these exams?5 One thing seems certain: Doctors of Laws repeatedly appear in Maltese controversies. Whether they were Maltese or Sicilian is often quite difficult to establish.

The records of the Maltese notary Giacomo Zabbara also glimpse at the working of the legal profession. In 1488, Imperia Ziguchi, who owed money to Notary Lorenzo Falzon, entered into an agreement with him in Zabbara’s acts: Falzon would be her advocatus in a lawsuit for the recovery of a house she claimed as hers. The contract also included the stipulation that she would only pay her advocatus his professional fees if he succeeded in winning her court case.6 In another claim which Bartolomeo de Astis had won in 1494 in the Maltese courts, he had been assisted by two lawyers, Giovanni di Bonaiuto and Jacobo de Basilico, Utriusque Juris Doctorum (UJD). The lawyer Bonaiuto had already been mentioned earlier as a commercial partner in the export of barley and other merchandise from Malta to North Africa.7

The Mdina Cathedral Archives house the documents of the Universitas of Malta (roughly the local government in the pre-Knights’ period). These are not very lavish with information about Maltese lawyers but do at times let slip some data. When in 1482 a court case came about between the bishop and the Universitas regarding an inheritance, each party appointed a notary to collect and record the evidence—Pietro Caxaro and Andrea Falzon. The two parties objected to their adversary’s choice on the ground of partiality as both notaries had previously acted as advocates for the party now appointing them. The Viceroy of Sicily cut the bickering short: the two notaries must carry out the task jointly.8

The ambassador of the Universitas to the Court of Sicily in 1526 was the lawyer Antonio Bonello UJD. He carried back an order to the Maltese authorities to stop delaying merchants from leaving the harbours immediately

when the weather turned favourable as this caused damage to the merchants and to the wellbeing of the island. 9 Dr Bonello was kept very busy by the Universitas, as lawyer and as ambassador.10

The Universitas functioned also by means of capitula, written queries to the sovereign in Sicily for guidance in anything which fell outside its jurisdiction, and these occasionally referred to Maltese lawyers, like one in 1494. The jurats told the Viceroy that Lorenzo Falzon and Giovanni Ciantar ‘were well versed in the law (curiali docti) but are not avvocati. They could however well serve the people, as very often lawsuits are lost due to the dearth of lawyers, and the population therefore suffers’. Sicily refused, almost indignantly.11

There are other sporadic mentions of Maltese lawyers much earlier than the 1530 watershed. Godfrey Wettinger reported ‘four or five Christian lawyers’ practising in Malta in the 1480s. One he mentions by name: Leonardo de Calavà, who acted as defence counsel of some Jews who allegedly had been, rather forcibly, baptised and had later returned to their Jewish faith, thus committing the capital crime of apostasy. In their 1486 trial, Calavà displayed creative forensic skills. He mostly attacked the credibility of prosecution witnesses, one with a formidable argument: how can the court give credibility to a witness known to fart shamelessly in the public street? The Calavà pleadings are the very first instances of a Maltese lawyer’s skills known to have survived in their entirety.12 It is rather sad that Maltese legal oratory starts with flatulence.

The final period of the Universitas, before the Order of St John took over in 1530, proves rather rich in Doctors of Laws working in Malta. There is the ubiquitous Dr Antonio Bonello, but also many other UJDs, like Dr Pietro Cassar, Dr Signorello Varisano, Dr Giovanni Bernardo Petrarca, Dr Antonio Bono (sometimes de Bono), Dr Blasco Lancia.13 Of these, only Dr Pietro Cassar, son of the Jurat Matteo was certainly a Maltese lawyer. He later rose to the rank of judge in the Captain’s court.14 All the others were Sicilian or Italian jurists sent to Malta by the Viceroy to investigate or determine legal issues that constantly bedevilled the island.

By now we have ascertained that lawyers were active in Malta well before the establishment of the Order in 1530. These seem to have fallen into two broad types: the advocatus, a person somehow versed in the law but without a formal doctorate conferred by a university, and the Utriusque Juris Doctor, or Doctor of Both Laws—UJD (or IUD, more commonly used in Malta, but which I discard, as those initials now refer to a contraceptive).

Doctors of Laws were entitled to be addressed by the honorific title of Magnificus, Magnifico, today only reserved for Notaries Public. In fact, in the earlier Libri Conciliorum the names of lawyers and judges are often followed by their law degree, but in the later ones this is sometimes omitted and substituted by the title Magnificus before their name.

Very incidentally, it is to a Doctor of Laws that we owe the very first known mention of pizza in Malta and in Europe. As early as 1583, Dr Salvatore Xerri UJD was hauled before the Inquisitor, charged with having eaten pizza in public on a Saturday. The Consultants of the Tribunal faced a wrenching dilemma: was it permissible to eat pizza on a day of penance when no other food was available?15

Was everyone charged with a criminal offence entitled to be assisted by a lawyer? The records do not furnish a clear answer, though the little evidence that survives seems to exclude this right. Fra Pierre de Sacconay, the Marshal of the Order, stood accused in 1587 of multa crimina, among others, of having vehemently contrasted the new rule that knights should not carry weapons, of having freed with violence a servant convicted of theft, and of having insulted the judge of the Castellania in the presence of the Grand Master. Sacconay expressly pleaded to be allowed to be assisted by a defence lawyer, but his request was turned down and he had to conduct his defence in person. Six years later, the whole criminal proceedings against Sacconay were annulled by the Pope in Rome, though not for lack of a defence lawyer.16

The Libri Conciliorum , besides throwing some light on lawyers, very occasionally help us to understand how Maltese judges operated. One

instance is in 1582 when the question arose whether the judges of the Mdina jurisdiction, the Corte Capitanale, were entitled to pocket a percentage of the fines they had imposed on delinquents in the criminal court. They petitioned Grand Master la Cassière not to deprive them of this privilege. The Grand Master in Council complied.17 This terrible abuse was only abolished in the early British period.

The question remains: how and where did Maltese lawyers obtain their law degree? Doctorates are only awarded by universities, which Malta lacked up to 1769.

The UJD degree in law refers to a ‘doctorate in both laws’, Canon and Civil, granted from the late Middle Ages by Catholic and Germanic universities, in Malta now substituted by LL.D. which means more or less the same, Doctor of Laws, not Law. But where did Maltese students obtain their law degree prior to 1769?

The situation is clear for those who graduated with a Doctorate in Both Laws to further their career in the church. For these, plentiful evidence survives that they earned their UJD mostly from the universities of Rome and Naples. Prof. Vincent Borg has undertaken very extensive research into the legal training of Maltese students in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and how many of them proceeded to Italy, sometimes on scholarships made available by the Cathedral Chapter; these, however, refer to those studying for the priesthood.18

But Mgr Borg also gives the following lists of Maltese laymen who obtained their law degree in Italy in the sixteenth century:

BEFORE 1550

Dr Antonio Bonello, before 1520

Dr Antonio Desguanez

Dr Giovanni Vassallo

Dr Nicola Xerri

Dr Michele Allegritto

Dr Antonio Bonello

Dr Ludovico Platamone

AFTER 1550 – ROME

Dr Francesco Xerri, 1553

Dr Nicola Pietro Xuereb, 1553

Dr Francesco Surdo, 1561

Dr Melchiorre Cagliares, 1563

Dr Valerio Micallef, 1563

Dr Giovanni Vassallo, 1563

Dr Giovanni Vincenzo Lubrano, 1570

Dr Giovanni Xara, 1580

Dr Cipriano Caxar, 1584

Dr Nicola Antonio Muscat, 1587

Dr Aurelio Vassallo, 1588

Dr Ascanio Surdo, 1591

Dr Antonio Bosio, 1594

Dr Giuseppe Turrense, 1594

Dr Valerio Mizzi, 1598

Dr Placido Abel, practised as Notary

Dr Martino Zammit, practised as Notary

AFTER 1550 – NAPLES

Dr Bartolomeo Tabone, 1590

Dr Giovanni Angelo Anastasio, 1593

It will be observed that some of these names do not appear in the bio-notes compiled below. This may be due to several reasons. Foremost, that the notes refer to lawyers who took up public offices, mostly with the Order. The others may have pursued their law career in the private sphere, village lawyers in the

better sense of the word. Or they may simply not have practised as lawyers after obtaining their doctorate.

As these lists do not contain several names of other known Maltese Doctors of Laws, it is fair to assume that those not mentioned obtained their law degrees from other Italian universities, like Catania, Palermo, Florence, or Bologna, not from Naples and Rome.

Dr Fabrizio Cagliola UJD (1604–1665) a leading Maltese lawyer, wrote a fascinating semi-autobiographical memoir, but fails to mention where and how he obtained his law degree.19 And Dr Ignazio Saverio Mifsud, himself a lawyer, who later wrote Cagliola’s biography describing him as ‘an excellent jurist and a superlative advocate’, similarly fails to mention anything about his training in law.20 Mifsud wrote about and praised several early Maltese lawyers, but not once does he reveal where they obtained their law degree.

There seem to have been very few dull moments in the lives of legal practitioners in Malta in the cinquecento—murders, woundings, torture at the rack, brothels, multiple mistresses, bribery and corruption, gay sex, pimping for virgins. Judge Cagliares was reputed to run three mistresses concurrently, while Judge Micallef frequented high-class bordellos. Dr de Spluchi was murdered, Judge Calli was grievously wounded. The Inquisition took a loving interest in Dr Cadamusto, Dr Xerri, Dr Cumbo, Dr Bonello, and others. Dr Bonello was also accused of attempting to murder the Grand Master. Dr Torrense availed himself of the services of a pimp to enjoy a young virgin, Dr Spatafora smarted under physical violence, Dr Xerri was embroiled in a gay sex scandal, and Judge Cumbo suffered public accusations of bribery and corruption. These are the ones we know of.

The data recorded in this article would have been more focussed and relevant had it been profiled together with clearer information about the legal structures within which the legal profession operated—the different courts, the professional hierarchies, the support systems. But, again, so very little is so far known about them. Just the barest outlines will have to suffice at this stage.

When the Order of St John took over Malta, various separate justice systems were in place. One catered exclusively for criminal justice against members of the Order suspected of having committed felonies. The Council of the Order transformed itself into a criminal court (called the Sguardio) which investigated, prosecuted, and adjudged the suspect knight. As the Order could not inflict the death penalty, in those cases in which it believed death to be the right reward, the Council first expelled the delinquent knight, and then handed him over to the ordinary criminal courts for a retrial which could end in execution.

The second system of justice was the Castellania, in place for anyone who was not a member of the Order. It comprised three courts: civil, criminal, and appeal. The judges, prosecutors, lawyers, and officials who manned the Castellania were almost exclusively Maltese. But Mdina also had its own regional courts, the Corte Capitanale and there was the Gozo Court which exercised general civil and criminal jurisdiction.

Besides the ‘lay’ jurisdictions, two separate ecclesiastical tribunals helped to clutter the legal panorama. The Bishop’s tribunals were mostly manned by ecclesiastical UJDs. Quite active too were the Inquisitor’s courts. Many Maltese lawyers found work there: as legal assessors (virtually deputy Inquisitors), as Promotori Fiscali, that is, directors of prosecutions, or as Advocates for the Poor.

The many Maltese lawyers identified below spent a busy life in these various courts. I have here reconstructed a tentative checklist for this period, with the sketchiest of bio-notes, some rather shocking. Lawyers elevated to the judiciary often reappear later as practising advocates. This is because judges did not, before 1815, have a lifetime’s security of tenure. They were appointed or reappointed periodically for short periods, usually for two years, in alternate autumns.

DR GUGLIELMO (BARTOLOMEO) ABELA (HABEL) UJD was, in 1567, delegated Advocate for the poor, widows and orphans or minors (pauperum, viduarum et pupillorum).21 Fra Gabriel Frias de Lara lost a court case against Dr Abela and appealed.22 In 1590, the Council elected him auditor of acts of governance of Valletta, Birgu (also known as Vittoriosa), Notabile, and Gozo.23 The Grand Master, in 1594, issued a decree favouring Dr Abela.24 There must have been bad blood between Dr Abela and Judge Giovanni Maria Mamo sitting in Gozo. The Council was called upon to adjudicate their difficulties on three separate occasions.25 Still active in 1599, Dr Abela is delegated to audit the affairs on Malta and Gozo.26

Ignazio Saverio Mifsud adds that Abela was universally acknowledged as the leading criminal lawyer of his times in Malta. In 1563, the Inquisition appointed him prosecutor. Grand Master Hugues Loubenx de Verdalle (1531–1595) also made use of his services when he came to redraft the Leggi e Costituzzioni Prammaticali in 1593.27

DR ANTONIO BONELLO UJD. There were two lawyers called Antonio Bonello in the sixteenth century, very likely father and son, and their periods of forensic activity overlapped. At this stage it is sometimes not possible to distinguish which of the two the records are referring to. Dr Bonello Sr graduated Doctor of Laws in the University of Catania, the oldest in Sicily, round the turn of the century,28 and was already very prominent as a jurist before the arrival of the Knights and quite likely the first Maltese to have obtained a Doctor of Laws; he found favour with the Order too. In 1565, the Council substituted him to Dr Nicola De Naro UJD in the criminal trial for sodomy against Fra Alvaro Fasano.29 In 1582, the Council appoints Dr Bonello (probably Jr) to audit the affairs of the officials in charge of Malta and Gozo.30

One criminal case in which Dr Bonello was involved is emblematic of the mobility of Maltese lawyers and their close interaction. In June 1595, Fra Girolamo Piscina stood accused of various crimes.31 Shortly after, he was murdered. On the

19 December, the Council plays around with five Maltese lawyers: it substitutes Dr Bonello to Dr Valerio Micallef in the Piscina proceedings and appoints Dr Pietro Muscat instead of Dr Paolo Cassar on the case of Dr Francesco Torrense.32 Incidentally, the Council found Fra Vincenzo Minardo guilty of the Piscina homicide and condemned him to a term of imprisonment.33 Dr Bonello had a very chequered career. Grand Master la Cassière accused him of attempting to poison him, in conspiracy with Inquisitor Domenico Petrucci.34 But Bonello had himself been a victim of the Inquisition when the physician Giulio Gratioso, his sworn enemy, had framed him with Domenico Cubelles, Bishop and Inquisitor, alleging he had turned Lutheran.35 In fact, the Inquisition did find Dr Bonello guilty of heresy in 1575.36

DR BARTOLOMEO BONELLO UJD, described as jurisperitus, is, in 1568, nominated Advocate for the poor, widows, orphans, or minors.37 In 1619, he appeared as witness in the will of the disturbed philanthropist Caterina Vitale.38

DR ANTONIO BOSIO UJD, better known as the leading archaeologist of the Roman catacombs, was born in 1575. Before channelling his energies to archaeology, he had a flourishing legal practice in the Roman Curia. He died in 1629.39

DR GALEAZZO CADAMUSTO UJD. In 1551, the Council ordered that a mislaid pouch, containing documents which identified the properties in Gozo belonging to those captured by the Ottomans in the great razzia of 1551, should be returned to Judge Cadamusto. 40 In 1569, the Council appoints Dr Cadamusto to audit the acta et gesta of the jurats of Notabile.41 Six years later, the appointment is renewed with the inclusion of the affairs of all the captains of the towns and of the forts of the islands. 42

Judge Cadamusto too had a close brush with the Inquisition. In 1582, he was investigated for witchcraft for having secretly written a book about divination through communicating with the dead.43

DR MELCHIORRE CAGLIARES UJD, also Cagliareno, Cagliarense, all indicating he was from Cagliari, was the father of the only Maltese bishop during the rule of the Order, Baldassare Cagliares (1575–1633). He first appears in the records in 1570, when he was appointed to audit the work of the Maltese officials of Mdina.44 Three years later he served as an Advocate for the poor, widows, orphans, or minors,45 and repeats the same audit.46 In the 1577 investigation into the atrocious murder (crudelissima morte) of Fra Giorgio Correa, Dr Cagliares played a leading role.47 Five years later, Cagliares, as criminal prosecutor, petitioned the Council in Italian to query the validity of certain legal enactments.48

Cagliares suffered excommunication at the hands of Bishop Tommaso Gargallo, known for his incompetence in anger management. In one of the Bishop’s several confrontations with the Grand Master in 1579, Dr Cagliares sided against Gargallo, who promptly excommunicated him. The Rector of St Paul’s in Valletta cut his excommunicated former friend dead when they crossed each other on Palace Square. The Inquisitor recorded Cagliares’ threat in its original Maltese: ‘Le tibzax, hecde kif fixkilt l’ohrajn, infixkil lilik’. 49

In the 1584 high-profile criminal proceedings against Fra Francesco Sommaia, captain of the San Giovanni, one of the Order’s galleys, Fra Francesco was charged with responsibility for the loss of his galley to the Venetians, of having abandoned a captured Ottoman vessel after having looted its merchandise, of having personally killed a soldier of his crew, and most unpardonable crime of all, of having served wretched meals on board, tavola sordidissima. The council arrested him and put him on trial. Dr Cagliares played a leading role in the prosecution.50 His career took an unexpected turn in 1589 when he tried to join the Order as a knight in the priory of Portugal, facing the strong, but unsuccessful opposition of the knights of that priory.51

But Cagliares, besides fathering bishops, left his mark in history for keeping three mistresses concurrently. To contain the prurient scandal, he slept with Marietta, her sister Caterina, and Marietta’s daughter. He believed strongly in family values.52

DR GIOVANNI CALAVÀ UJD was very likely the first Maltese lawyer to be promoted or confirmed judge after the Order had settled in Malta. It is reputed he advised Grand Master L’Isle-Adam in his negotiations with Charles V about the transfer of Malta to the Order, and helped with the drafting of the 1530 legal minefield, the deed of cession. The Grand Master rewarded him by granting him a title of nobility with an endowment of territories at Għajn Qajjet. Some lands of the wealthy Secretia, the Maltese office which administered the properties of the Sicilian crown on the island, were willed to the minor Joannella de Guevara, and Calavà was appointed to act as curator during her minority. Calavà numbered with those well in with the new rulers: ‘fideliter et diligentes obsequies Religionis nostre intendent’.53

DR GIOVANNI CALLI (OR CALI) UJD. In 1574, Calli is appointed to audit the affairs of the public officials of Valletta and Birgu.54 But the Grand Master later

removed him as suspectus, that is, because of a possible conflict of interest.55 The following year he was involved in the proceedings against Fra Onofrio Acciauoli, receiver of the Order in Messina, accused of having abused his office.56 In 1577, Fra Alberto Arrighi from Florence, professed only two years earlier, wounded Judge Calli ‘with copious bloodshed’.57 Dr Paolo Vella was appointed to compile the evidence, but shortly after was substituted by Dr Francesco Torrense.58 For wounding Calli, the Council condemned Arrighi to one year detention in the tower.59 The Council in 1590 imprisoned the turbulent knight for killing Polidoro Bernardino Mattei.60

The jurist later received the commission to audit all the affairs that fell under the jurisdiction of the Mdina officials,61 repeated in 1579.62 Shortly after, the minutes of the Council record that a challenge by Dr Paolo Vella and Dr Giovanni Vassallo against Dr Calli, was to be deemed unfounded.63 The Council again makes use of Calli’s services in the criminal proceedings against Fra Antonio de Vega and Fra Pedro Queiroz.64

But Calli was aware of his linguistic limitations. In 1584, when judge of the civil court, he petitioned the Grand Master to be relieved of hearing minor cases on the ground that his grasp of Maltese was poor. He recommended the appointment of the lawyer Dr Giovan Paolo Micci (Mizzi) who had a good command of Maltese, in his stead.65

In 1595, the Council substitutes Dr Gio Domenico Vella to Dr Cagliares in the criminal proceedings against Fra Andre de Martine called ‘Pellubier’.66 1597 saw Calli’s promotion to the Court of Appeal,67 confirmed in 1601.68

Dr Calli, son of Michele, drew up his last wills on 30 July 1616 and 26 June 1623 in the records of Notary Giovanni Carabott.

From Francesco Saverio Mifsud we learn that Grand Master Verdalle eventually promoted Calli to be his Uditore and the lawyer’s wisdom helped Verdalle solve ‘tutti gli intrigatissimi affari’ of the Order. Calli’s top legal achievement was the redrafting, together with other Doctors of Laws, of the Leggi e Costituzzioni Prammaticali, published by Verdalle in 1593. His speciality was criminal law, and

this earned him the post of prosecutor of the Inquisition in Malta. His legal opinions and reports, bound in two manuscript volumes, retained their popularity and authority for many years after his death.69

DR ALFONSO CASSAR UJD. Very little is known of this Maltese lawyer. He is not mentioned in the Libri Conciliorum, but he accompanied Dr Ludovico Platamone on the Maltese embassy to the Viceroy of Sicily in 1591. Mifsud refers to him as a Maltese advocate who enjoyed great credit and high reputation on the island.70

DR PAOLO CASSAR UJD was appointed auditor for the affairs of the local governments of Malta and Gozo in 1597 and again in 1601.71 He was the legal Assessor in the Inquisition proceedings against Giorgio Scala in 1598.72 The Inquisition employed Dr Cassar as legal Assessor between 1609 and 1614.73

DR GIOVANNI VINCENZO CAVALEVECCHIO UJD. He is found mentioned only once.74

DR AGOSTINO CUMBO UJD. Jurist who worked alternatively as a lawyer and as a judge. He remained notorious for his submission to Grand Master d’Homedes to pervert the course of justice. When Tripoli, belonging to the Order, fell to the Ottomans in 1551, the indignant eyes of the Christian world fell on Malta. D’Homedes, who had grossly neglected the defence of Tripoli, found himself accused of ineptitude. To shift the universal blame from himself, he had to find a scapegoat. The blame fell on the defenders of Tripoli, the valiant Fra Gaspar de Valies and all the other surviving knights.

D’Homedes accused them of passivity and cowardice in the face of the enemy and had them all defrocked. No longer knights, they were sent to the ordinary criminal courts, presided over by Judges Cumbo and Giovanni Vassallo, who condemned them to death. Fra Durand de Villegaignon publicly

and in a printed pamphlet accused d’Homedes of having bribed Judge Cumbo (‘a man easily corrupted, being always ready to sacrifice his conscience to his love of money’) to shift the blame from himself onto de Valies and the surviving defenders. A substantial sum of money, paid in gold in advance, did the trick.75

Cumbo is mentioned again in 1559 when the Council appointed him to assist the commissioners delegated to examine and report on a court case pending between three knights.76 Agostino may have been one of the first of the illustrious, often infamous, dynasty of Cumbo jurists who dominated the legal panorama of Malta during the whole duration of the Order’s rule.77 In 1563, the Council appointed the usual board of enquiry to investigate his conduct as judge.78 The year before the Great Siege, the Council tasked Cumbo to audit the performance of the Jurats of Birgu.79

Dr Cumbo, too, had fallen foul of the Inquisition. He was suspected of Lutheran sympathies, and either he, or his co-accused, suffered torture at the rack.

DR CAMILLO CUMBO UJD. Found mentioned only once.80

DR PIETRO CUMBO UJD first appears in the Libri Conciliorum when he was appointed Advocate for the poor in 1556.81 Like several other Maltese lawyers, the Inquisition investigated him on suspicion of Lutheran sympathies.82

DR NICOLA D’AGATHA UJD. The records mention him in 1546 when he was already a Judge, charged with a criminal trial. He asked the Council of the Order to suspend proceedings against Giovanni from Salonika for crimes he was accused of having committed in Tripoli when the North African town still belonged to the Order.83 D’Agatha was a Sicilian Notary from Mazara del Vallo who had settled in Malta with his wife Isolde, very likely the parents of the very first Maltese Jesuit, Fr Luigi D’Agatha SJ.

DR PASQUALE DE FRANCHIS UJD. His first mention in the Libri Conciliorum dates to 1574, when the Council appoints him to examine the affairs of Mdina, its Captain of the Rod, its jurats, the Castellan and the judges.84 In 1577, he, together with Dr Francesco Turrense, is appointed arbitrator in an important law suit between Fra Pietro Giustiniani, Prior of Messina and leader of the Order’s fleet at the Battle of Lepanto, and Fra Giuseppe Arborio. The two lawyers published their joint award, drafted exceptionally in Italian, in the Council.85

DR FRANCESCO GARIBO UJD was in 1586 made Advocate for the Poor86 and appointed judge of the civil court in 1599.87

DR GIORGIO GIANPIERI UJD was named in 1575 Advocate for the Poor, Widows, Children or Orphans.88 His public legal career included the auditing of the affairs of the cities of Malta and of Gozo in 1577,89 and commissioner for housing.90 After obtaining a Doctorate in Laws, Gianpieri entered the priesthood as a conventual chaplain in 1580, and eventually reached the very highest positions:

Vice-Chancellor, Uditore, all the way up to Grand Prior in 1592, though his election to the Grand Priorate was legally, though unsuccessfully, challenged in Rome.91 The following year, the Council imprisoned Fra Andrea Salvatore for ‘verba injuriosa et immmodesta’ bawled at Dr Gianpieri.92 His juridical expertise was determining in the promulgation and publication of the Leggi e Costituzzioni Prammaticali issued by Grand Master Verdalle in 1593.93 It is touching to record that on his deathbed, Verdalle wanted to receive the last sacraments at the hand of the former lawyer and of the Capuchin friars he had patronised.94

DR PIETRO DE GIOVANNI UJD is only mentioned in 1591 when the Council appoints him to audit the affairs of Valletta, Birgu, Mdina, and Gozo.95

DR FEDERICO DE GROMO UJD. The Council appoints this Doctor of Laws in 1598 to act as the conservator of the Order’s privileges.96

DR JACOBO LO PERNO UJD is mentioned in 1561 in connection with his appointment to audit the work of the Captain of the Rod of Mdina, and again the following year.97

DR ANTONIO MAHNUQ UJD. The ‘Mahnuq’, an old, notable and wealthy family from Gozo, had the surname italianised to Maccanuzio (once to Mahanne). The Order appointed him Judge of the Castellania in 159798 and of the civil court in August 1602,99 but in November the Jurats petitioned the Council to have him removed from some legal affair, and he is substituted by Judge Ascanio Surdo.100

DR GIOVANNI MARIA MAMO UJD. He was judge in the Gozo Court in 1599.101 The following year, the Council ordered the auditors to determine according to justice a petition by Dr Mamo.102 Dr Mamo acted as judge of the Castellania,

married Leonora Vassallo, and among his children numbered Dr Gregorio Mamo UJD, who, in turn, married Paola, daughter of Judge Ascanio Surdo UJD.103

DR FRANCESCO MEGO UJD. This very high-profile jurist, born in Malta of noble Rhodiot parents who had followed the Order after its expulsion from Rhodes in 1523, is repeatedly mentioned in the Libri Conciliorum; the first time in 1552 when Grand Master Juan d’Homedes appoints him as judge in all civil and criminal proceedings.104 By 1557, Grand Master de Valette entrusts him with the highest civil responsibility, that of Uditore, minister with judicial authority, the most powerful office in the civil governance of the island.105

Mego was also one of the Commissioners delegated in 1557 to report on the Moretto affair, which had significant international resonance.106 The following year the Council appoints Mego to the official investigation into a nasty brawl between two leading knights.107 Another major career leap came in 1560, when the Council appoints Mego as lieutenant and coadjutor of the Vice-Chancellor of the Order.108 And other promotions follow,109 including his nomination as Acting-Chancellor.110

Mifsud supplements some information about Mego. The Council eventually elevated him to Uditore, although the statutes laid down that only professed knights could aspire to that rank. He must have been among the first of a long series of Maltese Uditori, generally lawyers. Mego, together with Giovanni Vassallo, was responsible for the updating and redrafting of the Statutes of the Order willed by Grand Master Verdalle. Bishop and Inquisitor Domenico Cubelles appointed Mego assessor of the Inquisition, a post almost invariably held by a leading jurist.111

DR VALERIO MICALLEF UJD. In 1579, the Council entrusted Dr Micallef to represent it in the matter of its privileges and prerogatives in the Order’s disputes with the fiery Bishop Tommaso Gargallo.112 The following year, news of the theft of one the most treasured relics of the Knights from the sacristy of St John—a segment of the skull of St John encased in a disk of solid gold studded with

precious stones—shocked the Order. Micallef was one of the commissioners chosen to investigate the sacrilegious robbery. He found the culprit—Fra Vincenzo Pesaro, who had, sadly, already broken up the relic for melting.113

A number of knights, charged with having committed ‘various excesses’ in Messina in 1587, were investigated by Micallef.114 And when the terrible plague broke out in 1592, one of the measures taken was to appoint Micallef ‘assessor in causa de regimine sanitatis’.115 By 1594, the Council had selected him to audit the affairs of Valletta, Mdina, and Gozo.116 The following year, Micallef became judge of the Castellania (see also Dr Antonio Bonello, above).117

But Micallef left traces in the records not solely for his undoubted forensic skills. He was an assiduous frequenter of an exclusive, high-class bordello kept by Nardu Mamo in Ħaż-Żebbuġ. Mamo only admitted the highest knights and the classiest whores to his home in the village.118

DR GIOVAN PAOLO MICCI (MIZZI) UJD; DR VALERIO MICCI (MIZZI)

UJD. Two Micci lawyers are mentioned towards the end of the century. In 1584, Judge Calli proposed Dr Giovan Paolo Micci UJD to stand in for him in minor civil cases as Micci had a better grasp of Maltese than he did.119 Meanwhile, in 1614, the Inquisition promoted Dr Valerio Micci UJD, who had until then worked as Advocate of the Poor in that institution, to Assessor.120

DR NICOLA MUSCAT UJD is recorded in 1589 when the Council chose him to audit the affairs of Valletta, Birgu, Mdina, and Gozo.121

DR PIETRO MUSCAT UJD was elected auditor of the affairs of Malta in 1595122 and judge of the Castellania in 1597 (see also Dr Antonio Bonello, above).123

DR NICOLA DENARO (OR NARO) UJD is first mentioned in 1564 in connection with the criminal proceedings against the British knight Sir John James Sandelands, later convicted of the sacrilegious theft of precious silverware

from the church of St Anthony in Birgu. DeNaro’s instructions included the order to obtain evidence by ‘indicia, conjecturas et presuntiones’ (circumstantial evidence and legal presumptions) and, of course, recourse to torture.124 DeNaro also investigated Fra Alvaro Fasano, accused in 1565 of sodomy. He was, however, later removed from the case and substituted by Dr Antonio Bonello UJD.125 The Inquisition employed Dr DeNaro as legal Assessor in 1565 and 1566.126

DR GIROLAMO NICCO UJD is mentioned only once, in 1581, in the Libri Conciliorum, when the Council authorised the Prior of Lombardy to substitute Dr Nicco for himself in the lawsuit to recover the property of Matteo Minali.127

DR LUDOVICO PLATAMONE UJD from Gozo went through a brilliant legal career. In 1570, the Council required from him a complete audit of all that the Captain of the Rod, the Jurats, the Treasurer, and all the public officials of Mdina had done.128 Five years later, Fra Philip de Foissy was investigated for outrageous words hurled at Platamone, who was then judge.129

Platamone, like many other Maltese lawyers, had troubles with the Inquisition; he was investigated twice, the first time in 1574, the second time in 1579.130 One of the penalties the lawyer incurred in 1576 at the hands of the Inquisition was to subsidise to the tune of twenty scudi the purchase of liturgical books needed by the church of the Annunciation in Birgu.131 When in 1593 a bomb exploded on the doorstep of the twenty-seven-year-old Caterina Vitale, a turbulent pharmacist and sex-worker, the Council appointed Dr Platamone and two knights to investigate this ‘extremely serious and dastardly crime … an atrocious and pernicious example’.132 Platamone became judge of the Appeal Court in 1595.133

Mifsud adds that Platamone, when in private practice as a lawyer, had ‘interminable queues of clients’, and eventually rose to the highest ranks of the legal profession: various times judge of first instance and of the Supreme Court of Appeal, and Uditore of Grand Masters de Valette and la Cassière. He was designated ambassador of Malta, together with Dr Alfonso Cassar, to the Viceroy of Sicily in 1591. Apart from his great expertise in legal matters, Platamone was renowned for his outstanding integrity. He died in 1604.134

DR ROLANDO SCERRI UJD. In 1569, the Council appointed Dr Scerri to examine the work of the jurats of Birgu.135

DR ORTENSIO SPATAFORA UJD is the very first Maltese lawyer mentioned in the Libri Conciliarum, in connection with an outrage he suffered in the ‘public archives’ at the hands of an irascible knight, Fra Bartolomeo Vasco, in I542. The knight slapped the lawyer violently across the face. The Council of the Order

took a rather dim view of Vasco’s bravado and sentenced him to be detained in the smaller underground guva in Gozo for two months.136

DR ANTONIO DE SPULCHI, UJD is only known because a knight, Fra Antonio Bracalona (from Rome, professed in 1569), murdered him in 1579. As the Order had abolished the death penalty for its members, the knight was defrocked so that he could then be handed over to the ordinary criminal court to be tried and if found guilty, executed.137

DR ASCANIO SURDO UJD, son of another lawyer, Dr Francesco Surdo UJD, was born in 1563. He was made judge of the Castellania in 1597138 and after four years, raised to the Court of Appeal.139 Two years later he was confirmed in that Court140 and, in 1602, substituted Judge Dr Antonio Mahnuq at the request of the jurats in some legal matter.141 He rose to a meteoric and intense legal career, reaching the highest offices of judge and Uditore to Grand Master Alof de Wignacourt ‘for his doctrine and integrity’. He died aged 93.142

DR BARTOLOMEO TABONE UJD. He was appointed judge of the civil court in 1601.143

DR GIO DOMENICO TESTAFERRATA UJD mostly worked as lawyer for the Inquisition in the office of Promotore Fiscale, roughly, director of prosecutions. In 1598, he directed the investigation and prosecution of Giorgio Scala144 and served the Inquisition in a legal capacity all his professional life. He was later promoted to Assessor of the institution.145 According to Ciantar, Dr Gio Domenico was closely related to two other Maltese lawyers, Dr Giacomo Testaferrata, later judge of civil cases in the Corte Capitanale of Mdina, and Dr Paolo Testaferrata. He died in office around 1614.

DR FRANCESCO TORRENSE (OR TURRENSE) UJD. In 1570, the Council tasked Dr Torrense to audit the acts of governance of the Castellan of Birgu, Fra

Francesco Marzilla.146 Two years later, he was appointed Advocate for the poor, widows, orphans or minors.147 This lawyer, too, fell foul of the Inquisition. He was arraigned in 1574, found guilty, but pardoned after he retracted.148

After the wounding of Judge Calli in 1575 by Fra Alberto Arrighi, Dr Torrense replaced Dr Paolo Vassallo in the case against the vile-tempered knight.149 He was then delegated as arbitrator in the controversy between the Prior of Messina and Fra Giuseppe Arboreo (see Dr Pasquale de Franchis).150 His turn to act again as Advocate for the Poor, Widows, Orphans, or Minors came in 1588.151 But, in 1595, the prosecutor of the auditors petitioned the Council to have Torrense removed (see also Dr Antonio Bonello, above).152

Dr Torrense’s real surname was Rocchione (Turrense was the approximate Latin translation), and he was born in Savoia. By the time of the Great Siege he had already settled in Malta. He drew up his last will on 7 October 1599. He fathered two sons, both lawyers: Antonio, an illegitimate offspring, and Giuseppe. The two married into lawyer dynasties, the Cumbo and the Pontremoli.153 Dr Torrense, too, found himself embroiled in the wiles of Maltese whores. Domenico Carceppo accused the procuress Margherita Zammit of having prostituted his still-virgin sister-in-law, Lauria, with the lawyer. The affair lasted a couple of months and only ended when Domenico started turning heavy on Torrense.154

DR GIOVANNI VASSALLO UJD. The records first mention him when already a judge in 1547 in connection with the insults and invectives hurled his way by Fra Domenico de Sbach.155 Five years later, the Council subjected him to an investigation about his activity as a judge.156 Since these enquiries into the conduct of judges are rather common, it is not clear whether these were routine audits of members of the judiciary or specific investigations into some alleged misdeed. In 1561, Dr Vassallo was submitted to a similar ‘enquiry’.157 The year after the Great Siege, the Council appointed Vassallo Advocate for the poor, widows, and minors or orphans.158 By 1595, the Council designated him judge of the Castellania.159

Vassallo had already been judge of Corte Capitanale in Mdina in 1534. Ignazio Saverio Mifsud praises the lawyer’s forensic virtues: ‘always ready to take up the defence in lawsuits, shrewd in solving the difficulties that arose, sombre, but at the same time welcomed by everyone, especially by the illustrious Order of St John of Jerusalem’. Grand Master la Sengle entrusted to him the amendment, amplification, and commentary of the Statutes of the Order and rewarded him with liberali donativi. In 1590, Vassallo was honoured as Senator of Mdina.160 The major blot on Vassallo’s reputation was his participation in the conspiracy to condemn to death the knights who survived the loss of Tripoli in 1551 (see Agostino Cumbo above).

DR GASPARE VELLA UJD first appears as Advocate for the poor in 1601.161

DR GIO DOMENICO VELLA UJD. In 1596, Dr Vella substitutes Dr Calli in the criminal proceedings against Fra Andre de Martine.162 Three years later Dr Vella is made judge of the criminal court.163 That same year, the Council orders him to start criminal action against Fra Joseph de Guevara for subreptitia (deceptions) against the privileges of the Order.164 At the same time Dr Vella had also landed a job with the Inquisition as Advocate for the poor.165

The Dominican friars in Valletta appointed Dr Vella as their lawyer, and in 1603 rewarded him by the grant of a chapel in their church in lieu of payment. Dr Vella was the son of Salvatore and Antonella, and in 1589 married the bishop’s sister, Maddalena, daughter of Dr Melchiorre Cagliares.166 Between 1605 and 1609, the Inquisition employed Dr Vella as its legal Assessor.167

Dr Vella is described in the most flattering terms: ‘the depth of his knowledge, the wise prudence in all his acts, and the maturity of his deliberations’ earned him the post of Assessor and Consultor of the Inquisition and of judge in the local courts; he took part in the compilation of the municipal laws. He fathered another lawyer, Dr Melchiorre Vella UJD.168

DR PAOLO VELLA UJD. In 1576, Dr Vella was appointed Assessor in the criminal proceedings against Fra Antonio Brancaleone (probably Bracalone) and others.169 The following year he also took part in the prosecution of Fra Alberto Arrighi who had wounded Judge Calli.170 In 1576 and 1577, Dr Vella was appointed judge of the Corte Capitanale. Another member of the same family, Dr Giandomenico Vella UJD, occupied the same post in 1594.171 Dr Paolo is mentioned before in the records, but not as UJD.

DR GIUSEPPE XARA UJD. Found mentioned only once.172 Ciantar mentions another lawyer, Dr Orlando Xara UJD, active after 1530.173

DR FRANCESO XERRI UJD. Found mentioned only once.174 He took a prominent role in a gay scandal that ended in the lap of the Inquisition. The Doctor of Laws Nicola Pietro Xuereb, when a student in Naples, had succumbed to a strong physical attraction towards another student, Francesco de Buzietta, the couple living ‘like one soul in two bodies’ and everyone knew they committed the unmentionable crime—crimen nefandum.

The Inquisition in Malta took an interest in Xuereb—for his inquisitiveness about Lutheran and Calvinist literature. Xuereb was Dr Xerri’s first cousin, and the Inquisitor homed on Dr Xerri too, also under suspicion of sympathy for Lutheran heresies. In his pleadings to the Inquisition, Xerri capitalised on his honour—during the trial of a man charged with sodomy, Julio Xeibe had tried to corrupt him in favour of the accused. But, being a man of integrity, he had proceeded all the same with the torture of the gay suspect.175

DR GREGORIO XERRI UJD was Judge and Assessor of the Corte Capitanale in 1512.176

DR ORLANDO XERRI UJD was Judge and Assessor of the Corte Capitanale in 1581. 177

XUEREB UJD is mentioned in the gay scandal and the Inquisition investigation (see Dr Francesco Xerri, supra), became judge of civil cases in 1558, and Judge of the Corte Capitanale in 1562. He left Malta permanently for Sicily shortly after the Great Siege. He married twice: Margherita, daughter of Ugolino Bonnici, and Leonora Lagunna, and had numerous children from both spouses.178

P.12 An unidentified lawyer at the time of the Order. (Private Collection, Malta)

P.18 The lawyer Gaetano Bruno, Uditore of the Order. (Courtesy of the National Library, Malta)

P.23 Unidentified Maltese judge, eighteenth century. (Casa Vella, Attard / Courtesy of George De Gaetano)

P.27 (left) Portrait of a lawyer by Francesco Zahra. (Private Collection, Malta)

P.27 (right) Portrait of an unidentified Maltese lawyer, by Antoine Favray. (Private collection, Malta)

P.30 (left) The lawyer and judge Vincenzo Bonavita. (Courtesy of the Chamber of Advocates, Malta)

P.30 (right) A Maltese lawyer, eighteenth century. (Private Collection, Malta)

P.35 Antoine Favray, Portrait of Giovanni Nicola Muscat, Auditor of Grand Master Rohan, in his studio explaining a will to common folk, oil on canvas, 102 x 142cm. Ferdinando Inglott purchased the painting from the heirs of the Muscat family estate, as registered in the Acts of Notary Achille Micallef, 25 May 1888. (Private Collection, Malta)

1 Albert Ganado, Judge Robert Ganado. A History of the Government Departments from 1815 and Lawyers from 1666 (Malta: BDL Publishing, 2015), 251.

2 Stanley Fiorini, ed., Documentary Sources of Maltese History, Part II, No. 2 (Malta: Malta University Press, 2004), 133, 136, 138.

3 Ibid., 369.

4 Ibid., 660.

5 Ibid., and Part II, No. 4 (2013), passim

6 Ibid., Part I, No. 1 (1990), 309.

7 Ibid., 6.

8 Ibid., Part III, No. 1 (1996), 41.

9 Ibid., 167.

10 Ibid., passim.

11 Ibid., Part III, No. 2 (2014), 239.

12 Godfrey Wettinger, The Jews of Malta during the Late Middle Ages (Malta: Midsea Books, 1985), 62, 96, 102.

13 Stanley Fiorini, Documentary Sources of Maltese History, Part III, No. 3 (Malta: Malta University Press, 2016), 1197.

14 Ibid., 994, 1001.

15 Vincent Borg, Melita Sacra, Vol. 2 (Malta, 2009), 416.

16 AOM [Archivum Ordinis Melitae] 97, f. 95v, f. 98v; Bartolomeo dal Pozzo, Historia, Vol. 1 (Verona: Giovanni Berno, 1703), 280-281.

17 AOM 96, f. 66v.

18 Borg (2009), 73 et seq

19 NLM [National Library of Malta], Lib. Ms. 654.

20 Ignazio Saverio Mifsud, Biblioteca Maltese (Malta: Niccolò Capaci, 1764), 276.

21 AOM 92, f. 34v.

22 AOM 95, f. 198v.

23 AOM 98. f. 35.

24 AOM 98, f. 198v.

25 AOM 100, f. 130v, f. 145, f. 155.

26 AOM 100, f 127v.

27 Mifsud (1764), 82-83.

28 Giovanni Antonio Ciantar, Malta Illustrata, Vol. 2 (Malta: Giovanni Mallia, 1780), 402.

29 AOM 91, f. 134.

30 AOM 96, f. 79v.

31 AOM 99, f. 27.

32 AOM 99, f. 56.

33 AOM 99, f. 113v.

34 AOM 95, f. 224v; dal Pozzo (1703), 171.

35 Roger Ellul Micallef, ‘Sketches of Medical Practice in Sixteenth Century Malta’, in P. Xuereb, ed., Karissime Gotifride (Malta: University of Malta Press, 1999), 111.

36 Michael Fsadni, ‘The Dominicans’, in L. Bugeja, M Buhagiar, and S. Fiorini, Birgu, A Maltese Maritime City, Vol. 2 (Malta: University of Malta Press; Central Bank of Malta, 1993), 698.

37 AOM 92, f. 52v.

38 Notary Vincella de Santoro, 8.7.1616, and AOM 1990, f. 135. See, in this publication, the essay: ‘Tragic Tales of Slaves in Malta’, 105-113.

39 Mifsud (1764), 88-96.

40 AOM 94, f. 61.

41 AOM 92, f. 173,

42 AOM 94, f. 71.

43 AIM [Archivum Inquisitionis Melitae] Crim. 5C, f. 1037.

44 AOM 92, f. 212.

45 AOM 93, f. 101.

46 AOM 93, f. 156v.

47 AOM 94, f. 161.

48 AOM 96, f. 80r-v.

49 Carmel Cassar, Society, Culture and Identity in Early Modern Malta (Malta: Mireva, 2000), 160.

50 AOM 96, f. 179; dal Pozzo (1703), 248.

51 AOM 97, f. 189v, f. 190v; AOM 98, f. 15v.

52 Carmel Cassar, ‘The First Decades of the Inquisition, 1546–1581’, Hyphen, Vol. 4 No. 6 (1986), 225.

53 AOM 416, f. 193; AOM 414, f. 273v, f. 203; Lorenzo Schiavone, Pietrino del Ponte nella Storia dell’Ordine Gerosolimitano (Asti: Litografia Minigraf, 1995), 195.

54 AOM 94, f. 29.

55 AOM 94, f. 35.

56 AOM 95, f. 58, f. 63.

57 AOM 95, f. 37.

58 Ibid.

59 AOM 95, f. 52v.

60 AOM 98, f. 32.

61 AOM 95, f. 95v.

62 AOM 95, f. 151.

63 AOM 95, f. 162.

64 AOM 97, f. 181.

65 Cassar (2000), 161.

66 AOM 99, f. 107.

67 AOM 100, f. 20v.

68 AOM 100, f. 196v.

69 Mifsud (1764), 80-82.

70 Ibid., 78.

71 AOM 100, f. 22v, f. 196v.

72 Dionisius A. Agius, ed., Georgio Scala and the Moorish Slaves (Malta: Midsea Books, 2013), passim.

73 Alexander Bonnici, Medieval and Roman Inquisition in Malta (Malta: Franġiskani Koventwali, 1998), 307.

74 AOM 438, ff. 261r-v.

75 AOM 98, f. 94v; Louis de Boisgelin, Ancient and Modern Malta, Vol. 2 (London: Richard Phillips, 1805), 46-55. Boisgelin’s source is probably Villegaignon’s pamphlet, De Bello Melitensi (Paris, 1555).

76 AOM 90, f. 64.

77 Giovanni Bonello, Histories of Malta, Vol. 9 (Malta: Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti, 2008), 140-153.

78 AOM 91, f. 109v.

79 AOM 91, f. 176.

80 AOM 436, f. 272.

81 AOM 89, f. 94v.

82 Bonnici (1998), 13.

83 AOM 87, f. 82v.

84 AOM 94, f. 156v.

85 AOM 95, f. 6.

86 AOM 100, f. 47.

87 AOM 100, f. 121v.

88 AOM 95, f. 85v.

89 AOM 97, f. 143v.

90 AOM 97, f. 181.

91 Dal Pozzo (1703), 334.

92 AOM 100, f. 106.

93 Mifsud (1764), 73-76.

94 AOM 99, f. 6v, f. 16.

95 AOM 98, f. 57v.

96 AOM 100, f. 22.

97 AOM 91, f. 42v, f. 81v.

98 AOM 100, f. 20v.

99 AOM 100, f. 249v.

100 AOM 100, f. 258.

101 AOM 100, f. 130v, f. 135, f. 145.

102 AOM 100, f. 155.

103 Ciantar (1780), 457.

104 AOM 88, f. 120v.

105 AOM 89, f. 120v.

106 AOM 89, f. 99, f. 100. For the Moretto affair see Bonello (2008), 96-111.

107 AOM 90, f. 18v.

108 AOM 90, f. 126.

109 AOM 91, f. 61.

110 AOM 91, f. 87v.

111 Mifsud (1764), 30-31.

112 AOM 95, f. 142v, f. 143.

113 AOM 95, f. 197, f. 199v, f. 204v. See, in this publication, the essay: ‘Thefts from Churches in Malta’, 97-103

114 AOM 97, f. 91v.

115 AOM 98, f. 98.

116 AOM 98, f. 178v.

117 AOM 99, f. 34v.

118 Carmel Cassar, Daughters of Eve. Women, Gender Roles, and the Impact of the Council of Trent in Catholic Malta (Malta: Mireva, 2002), 38.

119 Cassar (2000), 161.

120 Alexander Bonnici, Storja tal-Inkizizzjoni ta’ Malta, Vol. 1 (Malta: Franġiskani Koventwali, 1990), 191.

121 AOM 97, f. 188.

122 AOM 99, f. 35.

123 AOM 99, f. 41.

124 AOM 91, f. 132, f. 133v. See, in this publication, the essay: ‘Thefts from Churches in Malta’, 97103.

125 AOM 91, f. 133v, f. 134.

126 Bonnici (1998), 307.

127 AOM 95, f. 283v.

128 AOM 92, f. 211v.

129 AOM 94, f. 48v.

130 Cassar (2000), 218.

131 Fsadni (1993), 700.

132 AOM 98, f. 147v.

133 AOM 99, f. 34v.

134 Mifsud (1764), 76-80.

135 AOM 92, f. 173.

136 AOM 86, f. 130v.

137 AOM 95, f. 126, f. 129.

138 AOM 100, f. 20v.

139 AOM 100, f. 196v.

140 AOM 100, f. 121v.

141 AOM 100, f. 258.

142 Mifsud (1764), 103-106.

143 AOM 100, f. 196v.

144 Agius (2013), passim.

145 Ciantar (1780), 484.

146 AOM 92, f. 195v.

147 AOM 93, f. 81v.

148 Fsadni (1993), 698.

149 AOM 95, f. 37.

150 AOM 94, f. 190v.

151 AOM 97, f. 143.

152 AOM 99, f. 40.

153 Mikiel Fsadni, Id-Dumnikani fil-Belt (Malta: Veritas Press, 1971), 49

154 Cassar (2002), 39.

155 AOM 87, f. 129v.

156 AOM 88, f. 118.

157 AOM 91, f. 25, f. 26.

158 AOM 91, f. 178.

159 AOM 99, f. 41.

160 Mifsud (1764), 27-29.

161 AOM 100, f. 175v.

162 AOM 99, f. 107.

163 AOM 100, f. 121v.