33 minute read

Features and Reviews

were a strong reminder of where Trump stands.

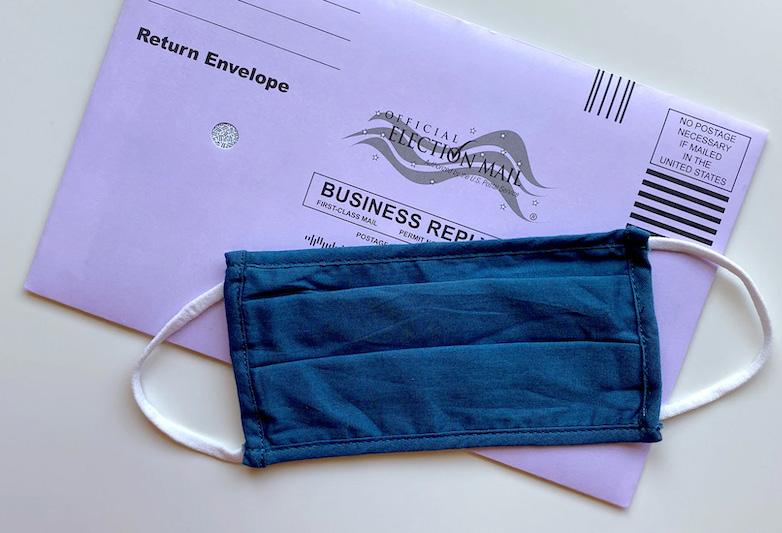

The other major theme of the 2020 election is of course, Coronavirus. During the 1918 flu pandemic, Woodrow Wilson never publicly spoke about it in the US, despite suffering from it himself. Many comparisons have been made throughout the year comparing 2020’s pandemic to the one of 1918. The pandemic did impact the midterm election, with very low turnout rates, mandatory mask wearing, and less in-person campaigning. However, the 1918 pandemic pre-dates welfare, the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, and any form of Medicare or Medicaid. In 2020, we recognise the need for governmental involvement and regulation to limit the damaging impact of COVID-19. Whilst many Western countries have failed to prioritise collective security over personal freedom, the US is unique in how politicised preventative measures have become. Throughout his campaigning in the summer, Trump refused to wear a mask; held large, infectious rallies (like that in Tulsa); and declared the US as ‘re-opened’ at the end of April. Even when recovering from his own bout of the virus, Trump downplayed its severity to the American public. Elections against an incumbent tend to be a referendum on their presidency, and in 2020 the referendum on Trump’s handling of the pandemic was resoundingly clear. More important than the 1918 midterms then perhaps, was the 1920 presidential election. Harding, the Republican who would go on to win, called for a return to ‘normalcy’, amid social and political upheaval. Wilson had failed in his promise to prevent US involvement in World War I and failed in his negotiations of the Treaty of Versailles. Harding’s win in 1920 saw the biggest margin in popular vote in presidential history, suggesting that perhaps Trump’s loss was less surprising given historical context.

Advertisement

Given the examples of how prejudice impacted the 1964 election, and the pandemic in 1920, the 2020 Presidential election seems somewhat less unique. Trump’s failure to denounce white supremacy, his incitement of violence, and primarily white base all cost him significantly as did Goldwater’s failure to denounce extremism and reliance on white southerners as his base. Equally, Wilson’s refusal to comment on the Spanish flu and massive failure at the polls in 1920 are an example of how poor handling of a virus can severely impact the polls. Trump’s failure to act on Coronavirus, however, was much more significant in 2020, as society has acknowledged the need for big government.

Public History in the Age of COVID-19

By Mhairi Ferrier

2020 has been a significant and eventful year, which has seen the spread of Coronavirus and lockdown restrictions across the world, as well as a global fight against social injustice and systemic racism. This is a good time to discuss and reflect on what it has been like working in history-related roles during this time. Thank you to Dr Sarah Laurenson, Rosie Klutz, Dr Sheonagh Martin, Craig Woollard, and Catherine MacPhee for reflecting on their work in 2020.

For Dr Sarah Laurenson, Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary History at the National Museum of Scotland, COVID-19 became a priority collection project due to the significant contemporary nature of the pandemic. Sarah explains that due to the interdisciplinary way that the museum collects “there was an opportunity to collect the material impact of COVID-19 in a way that was different to how other organisations might go about it”. The museum has been collecting across six themes: public health, hospitals and treatment, politics, the economy, tourism, education and everyday life. Curators have been utilising ‘post-it’ note collecting, by identifying items and asking people to keep them until curators have a chance to review the material, and until restrictions on movement are eased in a way that enables the objects to be collected.

As a result of restrictions across the country, Sarah points out that “social media has played an interesting role in collecting our objects”. Social media has allowed potential objects, such as a painted pebble decorated by a family in Shetland, to be identified. This is an object that tells a story about more than just its face value - the pebble highlights different experiences of lockdown across Scotland: while some felt lucky to have a beach on the doorstep, others living in urban areas did not have the same access to outdoor spaces during lockdown. This item also brings an international connection as the family also ran fundraising concerts of traditional music online to raise money for a local NHS appeal which was watched and enjoyed by people across the globe.

Image: Interior of the National Museum of Scotland, image sourced from Google Arts and Culture.

Helping people understand what contemporary curating is all about has become easier in some ways, as Sarah notes that people “understand that this is a moment in history that they are living through and that it should be documented.” That idea of these COVID times being recognised by the general population as historically significant has also been something we have seen reflected in the media throughout 2020.

Visitor heritage attractions have seen many changes, such as introducing a one-way system, restrictions of visitor numbers as well as having less than half the staff and volunteers on shift at any one time. This has brought several changes to both the National Trust for Scotland’s Georgian House, as well as Kiplin Hall. The Georgian House is a restored building designed by Robert Adam in Edinburgh’s New Town located on Charlotte Square, while Kiplin Hall and Gardens is a Jacobean house dating back to the 1620s in North Yorkshire.

Image: Interior of the Georgian House. Source: The National Trust for Scotland. “Returning to Kiplin [Hall] was a very different experience as the processes I had been used to for four and a half years had changed and it felt like starting a new job all over again,” says Rosie Klutz, Front of House Manager, who was placed on furlough until June. Due to social distancing measures, the number of volunteers has had to be reduced by half. “Without our dedicated team of volunteers, we simply cannot open,” Rosie states. “Thankfully, with the help of staff, we managed to open safely and still provide a COVID-safe and enjoyable experience for our visitors.”

Similarly, at the Georgian House volunteer numbers have been reduced significantly. A typical day would see three sets of volunteers working approximately two and a half hour shifts, however, in these COVID times, to keep the number of households to a minimum, there is only one volunteer shift per day, with shifts lasting four and a half hours. Many volunteers are enjoying this new challenge. “After forty-five years of having those rotas and now having a break from that, volunteers see that it’s not so bad,” says Dr Sheonagh Martin, The Georgian House’s Visitor Services Manager.

The everchanging guidelines have meant that visitor attractions need to be quick to react and implement new operating guidelines. “We had five weeks to prepare for the opening and part of that was asking how we could do that safely for staff, volunteers and visitors,” Sheonagh adds. “We opened with a capacity of eight and within four days we had to reduce the capacity to six [due to changing government guidelines] every half hour.” Rosie agrees that this has also been a challenge but concludes that “luckily our marketing and communications officer is very much on the ball, and she made sure all of the info was updated quickly and put onto our social media channels as well as making sure we had newspaper coverage.”

Craig Woollard, an Archive Digitizer at Motorsport Images, has had to adapt to working at home when the bulk of his role involves scanning motorsport related photographs dating back to the late 1800s. With the cancellation of the Australian Grand Prix, the Formula One Season opener, Motorsport Images pre-empted restrictions and began working at home two weeks before the national lockdown started.

“We have been able to adapt quite nicely, we’ve got machines in the office that we can connect to remotely that we can use to sort out our servers or uploading to the website,” Craig explains. Projects, such as the 1970s Formula Two photographs Craig was digitizing, had to be placed on hold while working at home, while others could be continued, such as keywording of pictures.

Motorsport Images was preparing for a move to a new building when the lockdown was imposed and as such many items in the archive were boxed away. Prior to the second English lockdown, staff were able to work in the office for part of the week, Craig observes “the whole environment is different, so it’s almost like starting a completely different job in some ways”.

Recent events, such as the Black Lives Matter Movement, have also offered the opportunity to reflect on the narratives being presented to visitors at many heritage sites and museums. “There is a project which is called ‘Facing Our Past’ and it is to do with looking at the connection of Trust [National Trust for Scotland] properties with the Transatlantic Slave Trade and also now we are opening it out to the wider impact of the Empire,” says Sheonagh Martin. “I’m part of a research group for that and I think that’s very important.” Catherine MacPhee, a trainee archivist at Skye and Lochalsh Archive Centre, felt strongly about

Image: Exterior of Skye and Lochalsh Archive Centre. Source: Highlife Highland, https://www.highlifehighland.com/skye-and-lochalsh-archive-centre/

the need to collect protest materials from local BLM protests on the Isle of Skye. Usually, archives do not actively collect; rather, they have items donated to them, but Catherine was determined this is a moment that would not be missed by the archive. “Before the pandemic hit in March, we had already been having discussions about the underrepresentation of groups in the archives, so these materials link in quite well with a number of projects,” Catherine says.

In Portree, young people held a socially distanced protest in Sommerled Square, while more rurally located people had their own local acts of solidarity – materials and images have been collected from events across the island. Catherine observes that “this whole movement has opened the floodgates for this discussion, and I think it’s great.” She also tells me that we must “encourage people to be critical of their history”, an extremely important observation. Catherine hopes to keep the discussions going in the archive and across the island as she does not want the items just to be boxed away. the benefit of COVID changes in terms of how spreading out visitor areas – admissions, shop and tea-room – has been useful and is something they are looking to incorporate permanently. At the Skye and Lochalsh Archives Centre, the new prebooked appointments have led to a changing demographic of people visiting the archive, and this is something Catherine hopes will continue, and they can build on for the future, ensuring the archive represents all groups who live on the island. Collecting COVID related items continues for Sarah, as they are working to navigate this safely with more restrictions again being implemented and the varying restrictions across Scotland.

2020 has been a time for change, and we can definitely see that reflected in historyrelated fields. It has also allowed people to revisit or begin projects that normally there would not be time for. At the Georgian House, Sheonagh hopes to revisit the resources they produce for primary aged children, while also creating a secondary school programme. Craig has found the time to correct incorrect information on Motorsport Images’ online cataloguing, which has been caused by algorithms adding the wrong information, this is something that there is not usually time for. At Kiplin Hall, they have seen

The Portrayal of the AIDS Pandemic and Homophobia in ‘Dallas Buyers Club’

By Kat Jivkova

A major twentieth century pandemic was undoubtedly the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), caused by the HIV virus. This disease was first identified in 1981 following the publication of an article concerning the causes of a rare lung infection – Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) – by the U.S. Centre for Disease Control (CDC). The article focused on the impacts of PCP on five gay men whose immune systems had deteriorated after their diagnosis: this came to be known as the first official reporting of AIDS. The events that ensued saw rigorous research surrounding this ‘mysterious fever’ and an urgency to suppress the pandemic, as demonstrated by the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) mitigation strategy in the 1990s. All of this was coloured by a persistent homophobia.

The 2013 film Dallas Buyers Club illustrates the gritty realities of the pandemic through the tale of real-life character Ron Woodroof (played by Mathew McConaughey) and his experiences after testing positive for HIV. Opening in 1985, the film shows Woodroof’s daily life before the diagnosis – his work as an electrician and part-time rodeo cowboy. He abandons both following a harrowing hospital visit in which he is told that he has only thirty days to live. The film circles the subject of fighting death, reinforced by the narrative theme of Woodroof’s interest in AIDS treatment. The protagonist begins by obtaining samples of azidothymidine (AZT), after learning that pharmaceutical companies in Texas have been trialling this possible cure. However, the medication soon takes a toll on him, partly due to his persistent alcohol abuse. This portrayal of AZT is accurate in various aspects. Despite passing stringent tests, the drug caused serious sideeffects, including nausea, chronic headaches, and muscle fatigue. Essentially, it was not a cure for patients, but rather a means of surviving for longer, arguably causing more problems than it solved. Nonetheless, it was fast-tracked for approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) due to immense public pressure, resulting in human testing at a very early stage and controversial studies with skewed results. In real life, Woodroof also publicly campaigned against the use of AZT, as the film suggests, stating “that stuff will eat you up”, further illustrating the controversy surrounding AIDS treatment at the time.

It is of no surprise that Woodroof actively sought out and intensely researched different treatments to discover new ways of helping HIV/AIDS patients. In the film, he begins to smuggle non-FDA approved drugs from Mexico and later establishes a membership-based institution in which he supplies illegal drugs to people in the same position as him with the help of Rayon (played by Jared Leto), a trans woman and AIDS patient. Once again, the film coincides with the reality of Woodroof’s situation in the 1980s. He used elaborate disguises, usually dressing up as doctors or priests, to bring drugs across borders, even hiding this medication in a suitcase of dry ice when moving through customs in Japan. Furthermore, the film accurately recognises Woodroof’s involvement in several lawsuits with the FDA. For example, he sues the Food and Drug Administration over his right to supply members of his club with Peptide T for dementia, a symptom of AIDS. The film provides valuable insight into the difficulties involved in seeking reliable treatment for AIDS, and the FDA’s failure to invest more time into the approval of other drugs to treat the virus.

One reason for the FDA’s ineffectiveness concerning AIDS is rooted in the homophobic attitudes which ran rife in the 1980s and were fuelled by the media’s depiction of the virus as a ‘gay plague’. The epidemic was assumed by some to have arisen in the U.S. after the Stonewall Riots in New York City, a revolution in 1969 which electrified an international gay rights movement. Widespread unprotected sex within densely populated cities such as New York resulted in a large proportion of young gay adults testing HIV positive at this time, informing these prejudicial attitudes. It was in another publication released by the CDC in 1981 that the ‘official’ target of AIDS transmission became ‘homosexuals’, an idea subsequently reinforced

by a New York Times article that described AIDS as the ‘gay cancer’. The subject of homophobia is addressed throughout Dallas Buyers Club, with Woodroof initially exhibiting homophobic attitudes. The film is exceptional in showcasing his character development: after it is revealed that Woodroof is HIV positive, his friends turn against him, leaving Woodroof to experience first-hand the isolation that the gay community undeniably felt at the time of the crisis. The film strays from fact by introducing Rayon as his business partner in the running of the club and, although Rayon is a fictional character, it is assumed that director Jean-Marc Vallee introduced her in order to more explicitly capture Woodroof’s personal growth. By the end of the film, the LGBT+ community is what Woodroof depends on the most.

Dallas Buyers Club deserves praise for several reasons. Firstly, Mathew McConaughey’s exceptional performance as Ron Woodroof evokes an appreciation for the ambition Woodroof must have channelled in order to battle against his illness and distribute drugs to other sufferers, managing to push his morals forward even in the face of adversity. The measures McConaughey personally employed for this representation surpassed expectations – he lost an extreme amount of weight in order to depict Woodroof’s physical frailty. The film also relies predominantly on research into the real-life person responsible for the buyers’ club. This was a meticulous process, which began over twenty years prior to the film’s release. It was a reporter for the Dallas Morning News, Bill Minutaglio, who first conducted research into buyers’ clubs for AIDS patients, catching the interest of screenwriter, Craig Borten. Ultimately, Borten was able to interview Woodroof just before his death with the hope of creating a film about his life. The film deals with topics that were taboo during the 1980s: it raises awareness of the AIDS pandemic and the hardships of the LGBT+ community, who were victims of a homophobic society at a time of acute suffering.

However, one of the biggest flaws of the film is the lack of queer representation. By not hiring any queer actors to play important roles within the film, despite its focus being on the experiences of those within the LGBT+ community, Jean MarcVallee missed a brilliant opportunity to represent marginalised people in film. If a remake of this film is ever made, representation should be at the forefront of the next director’s thoughts.

Ultimately, Dallas Buyers Club portrays AIDS in a unique way, demonising the FDA and its problematic fast-tracking of an AIDS ‘cure’ in response to growing pressures during the pandemic. Although the film is ambiguous in its presentation of the AZT drug, this was achieved intentionally, to help the viewer understand Woodroof’s perspective on FDA-approved medication, and his anger at its side effects after trialling it. The film also shows the way that the media’s representation of AIDS triggered specific societal attitudes which labelled the virus a ‘gay disease’. Of course, studying the flaws of Dallas Buyers Club is also essential as it will enable directors tackling AIDS-related topics to improve the virus’ depiction in future films and avoid issues around queer representation.

Lovecraft Country: History Through Poetry

By Rebeka Luzaityte

Lovecraft Country is effortlessly evergreen. Based on a 2016 novel of the same name, the HBO series explores some of the supernatural horror elements developed by the infamous writer H.P. Lovecraft, with added themes of racial segregation in mid-twentieth century United States. The use of historical events as both a backdrop and an integral part of the narrative is unparalleled by any other TV series in recent times. Lovecraft Country employs many of the same filmmaking techniques as Hollywood blockbusters, including but not limited to time traveling, a love story, and a hero upon whom a whole community relies for survival. However, instead of providing blockbuster escapism, the programme’s use of poems such as Gil Scott-Heron Whitey’s ‘On The Moon’ and Sonia Sanchez’s ‘Catch Your Fire’ yields a poignant and nuanced socio-political critique regarding the way the African American community has been consistently marginalised in the US.

The show’s main character, Atticus (Tic) Freeman, played by the incredibly talented Jonathan Majors, is a young veteran who has come back home from serving in the Korean War, 1950-1953. Upon his return, he discovers a letter from his missing father, Montrose, (Michael K. Williams) inviting him to discover his family legacy in Ardham, Massachusetts, a fictional town based on Salem, Massachusetts. It is a trap, but Tic doesn’t know it as he, his uncle George (Courtney B. Vance) and school friend Leti (Journee Smollett) set out to find him. What follows are some of the most intricately delivered representations of the reality of black Americans in mid-twentieth century USA.

Specifically, Lovecraft Country relays the ways in which Jim Crow laws, which were introduced in former Confederate states after the abolishing of slavery in 1865, and which then spread across the country as black people migrated in search of employment and a better life, effectively upheld white supremacy in the US. The social effects of this are explored in the series by way of poetry, which can be heard recited in the background of several scenes. In a series where a shot of a group of white men generates as much horror as a human morphing into a vampire-like beast, the fusing of horror and the supernatural with socio-political critique is what makes the show stand out from almost anything else of the last few years.

One of the historical events used in the series is the Tulsa massacre of 1921, during which white supremacists set the thriving Black neighbourhood of Greenwood, Oklahoma ablaze. An eyewitness account of the events was discovered in 2015, written by Buck Colbert Franklin. The manuscript details all the horrifying ways in which the so-called ‘Black Wall Street’ was destroyed by bombs raining from the planes above: ‘“Where oh where is our splendid fire department with its half dozen stations?” I asked myself. “Is the city in conspiracy with the mob?”’ In this episode, titled ‘Rewind 1921’, Lovecraft Country incorporates Sonia Sanchez’s poem ‘Catch the Fire’ (the full title is ‘Catch the Fire (For Bill Cosby)’, but, naturally, the latter part is omitted these days). In a heart-wrenching scene during which a gang of white people set a house on fire with a black family still in it, Sonia Sanchez’s voice is heard reciting:

“Where is your fire, the torch of life full of Nzingha and Nat Turner and Garvey and DuBois and Fannie Lou Hamer and Martin and Malcolm and Mandela”

Sanchez’s poem, written in 1994, is inspired by the need for change in the socio-economic and political status of black Americans in the US.

While the Lovecraft Country episode is set in the 1920s, the unerlying causes of a decades-long fight for black liberation unifies the poem and the events on screen. It also services as a reminder of the brutal past of African Americans and the

Image: A scene from Lovecraft Country, courtesy of HBO. Source: New York Times, https://www.nytimes. com/2020/08/07/arts/television/living-while-black-in-lovecraft-country.html

While the Lovecraft Country episode is set in the 1920s, the underlying causes of a decadeslong fight for black liberation unifies the poem and the events on screen. It also serves as a reminder of the brutal past of African Americans and the ways in which their activism relies on the unification of the community, of maintaining and passing on ‘the fire’.

Another way in which the series utilises a historical event and the poetic criticism that followed it is seen in the episode ‘Whitey’s On The Moon’, named after Gil Scott-Heron’s poem of 1970. In the episode, Tic discovers his powerful magical heritage, which the show’s white villain attempts to exploit in order to become immortal. When Tic is forced to perform a ritual that may potentially kill him, Scott-Heron’s poem is the preliminary non-diegetic sound of the scene:

“I can’t pay no doctor bill But Whitey’s on the Moon Ten years from now I’ll be payin’ still While Whitey’s on the Moon”

Scott-Heron’s poem was inspired by NASA’s successful 1969 Moon landing; more specifically, the amount of resources being funnelled into this mission, while Americans, particularly black Americans, were destitute. The US government were quick in portraying the Moon landing as an achievement for all mankind, despite the black Americans who protested on the day of the launch. Thus, the distorted priorities of the government and its economic exploitation of black Americans were effectively overridden in favour of positive PR for the US. Not unlike Sonia Sanchez’s poem and its transparent socio-political commentary, the show’s use of Scott-Heron’s poem further exemplifies the structurally racist confines of black people’s economic and social contributions to American society, which is then utilised for the advancement and mythologising of white Americans and their history.

Lovecraft Country expertly balances socioeconomic and political critique of the fundamental attitudes on which the US is built, while avoiding diminishing the African American community to a monolith or their characters as mere motifs. By way of using Scott-Heron’s and Sanchez’s poems, the series effectively demonstrates the ways in which the marginalised African American community is forced to fight prejudice in a society built on those very principles. Lovecraft Country is a series that explores history through the very people that made it.

Plague and Paganism: An Experimental Take on the Greek Gods.

By Simone Witney

Thucydides’ famous description of the outbreak of typhoid fever in 430 BCE contains details with which we are ourselves familiar: the lack of sufficient knowledge to enable physicians to respond adequately, the lack of any preparedness from the government, the despair of those suffering severe effects, the rapid nature of its spread. Yet, we hear little about the consequences on the economy and the institutions.

Can we imagine experiencing a pandemic without the internet? As Covid has come upon us at a time when the web is intrinsic to our civilization, there has been a huge shift in the part it plays. The virus has shown us that so many of our ways of conducting our lives and business can be completely transformed. The high rent office in London, for example, with attendant lunches, cappuccinos, after work drinks, and international travel has simply dropped away while the environment begins to sing. The fall-out of Covid for our economy is extreme in its diversity, but while this is a time requiring imaginative solutions, it is also a time not to be naïve about the benefits of chaos for capitalism. This has been discussed in relation to great political changes, but there are comparisons to be made with the current situation (see bibliography for further reading). It is time for some Apollonian thinking.

How is it constructive to think about Greek Mythology?

Over centuries of being redescribed for the culture of the day, the potency of the Greek gods has drained away (this is not quite true, of course, nor do I wish to imply that artists should not be free to use the imagery that comes to hand). Their rich complexity is called ‘irrationality’, their fluid relationships ‘dysfunctional’. A few survive as brand names: Hermes, the delivery company, Athena, the poster company. The reduction is so endemic that even scholars seem puzzled on how to take this preposterous pagan prescientific tangle of folksy tales seriously.

However, the ancient Greeks – with a few exceptions – did take their rituals and myths seriously and, while this may not be a difficulty if religious practice is intrinsic to your life, the secular among us need to be reminded that ritual and myth were as integral to their lives as the internet is to ours.

I suggest two ways of restoring our respect for the gods. One is to recognise that in a time before scientific humanism gave us such power over our fate, when we had a less aggrandised conception of ourselves in relation to the natural world, this entailed an honouring of this relationship as a given principle governing all aspects of life. Rituals, sacrifices and festivals were the vehicles of this honouring: whether you poured a glass of wine to Hermes – who took spirits to Hades – before bed to ensure waking in the morning, or to the nymph of a stream that watered your crops. You acknowledged your vulnerability to forces outside your control. In our present circumstances, and with the ethical shift from exploiting to sustaining the environment, this is not hard to embrace.

The second is that we try to inhabit the diachronic symbolism of these deities so that we may reconnect with them. In other words: how might we think of them as beings active and powerful in our own times? Indeed, why should we think about them particularly in relation to the current pandemic? Let’s take Apollo for example, the god who sent a plague on the Greeks at Troy.

Apollo: Back to Black or Sunny Afternoon?

He is often called the sun god, but this is due to his link to Helios, who is the sun god, and to

Egyptian Horus. They do all shine, however, and like the sun, Apollo can both heal and destroy. Due to his mastery of memory through poetry, he can illumine the future with a prophesy or withhold it just as the sun suppresses its own light. His is the kind of light which sends a ray to the end of a tunnel, or over a mountain. His vision is unerring, his mind functions in shafts, at high speed, with unwavering accuracy. Rarely seen without his bow, he operates like a Zen archer.

The quality of his thinking can be seen in the following story: the god Hermes, finding a tortoise one day, immediately saw its potential. He killed it and used it to invent the lyre. He then stole some of Apollo’s sheep and used it to win Apollo’s forgiveness and having done so, promptly lost interest. His is the mobile genius of the moment, but Apollo’s genius lies in taking the longer view. He knew exactly how to realise the potential of this new invention. He strode up to Olympus and, playing his lyre, lit up the deities with joy until they found themselves singing and dancing, for the first time, in a state of rapture (Iliad 1.603). He had given them – and human beings via the Muses – the gift of memorialising experience through poetry and music, the gift of learning from the past and of bringing ecstasy to the present. and water for growth and Apollo made the laurel sacred to him. So, Daphne became a symbol of integration and emergence. Apollo spent his youth travelling over Greece looking for places to found his sanctuaries. (Homeric Hymn 1 14045 and 2. 214-254). While Hermes is the god of journeys and transitions, Apollo is a god of the networks that make civilisation possible: a god of roads, of architecture, of infrastructure.

At the beginning of the Iliad, he sent a plague to the Greek army because their leader, Agamemnon, had overstepped the boundary between the human and divine by taking captive the daughter of Apollo’s priest, placing self-interest above the well-being of his army. What boundaries do we disrespect? Apollo can constellate for us a combination of the ecstatic and the pragmatic, which helps us appreciate why he was one of the most feared and revered of the Olympians. It also helps us turn our own attention to the way in which imagination can function in both these modes to help us look beyond the present and envisage our own future.

He was, as all the gods were, energetic in his loving. Daphne was the daughter of a river god – but fire and water? It would not have lasted. Gaia, the personification of the Earth, turned her into a laurel tree whose nature it is to use sun

Images: Apollo and the Muses, oil on canvas pentyptych by Charles Meynier, Cleveland Museum of Art. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Bibliography

Morality Vice: Combatting Venereal Disease in Progressive Era America

Adams, James H. Urban Reform and Sexual Vice in Progressive-Era Philadelphia: The Faithful and the Fallen. Lanham: Lexington, 2015. Alonso, Harriet. Peace as a Women’s Issue: A history of the U.S. Movement for World Peace and Women’s Rights. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1993. Brandt, Allan M. No Magic Bullet: A Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States since 1880. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985. Jenkins, Philip. “A Wide-Open City:” Prostitution in Progressive Era Lancaster’, Pennsylvania History: A Journal of MidAtlantic Studies 65, No. 4 (1998): 509-526. McGerr, Michael E. A Fierce Discontent: the Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870-1920. New York: Oxford university Press, 2005. Matsubara, Hiroyuki. “The 1910s Anti-Prostitution Movement and the Transformation of American Political Culture.” The Japanese Journal of American Studies 17 (2006): 53-69. Perry. Nicole. “Diseased Bodies and ruined reputations: Venereal disease and the Construction of Women’s Respectability in Early 20th Century Kansas.” PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2015. Shah, Courtney Q. “’Against Their Own Weakness’: Policing Sexuality and Women in San Antonio, Texas, during World War I”. Journal of the History of Sexuality 19, No. 3 (2010): 458-482.

The Metic in the Wake of the Athenian Plague

Kamen, D. Status in Classical Athens. Princeton University Press, 2013. Loraux, N. Born of the Earth: Myth and Politics in Athens. Cornell University Press, 2000. Martínez, J. “Political Consequences of the Plague at Athens.” Graeco-Latina Brunensia 22 (2017): 135–146. Morens, D. M.; Littman, R. J. “Epidemology of the Plague of Athens.” Transactions of the American Philological Association 122 (1992): 271–304. Papagrigorakis, M. J., Yapijakis, Ch., Synodinos, Ph. N., & BaziotopoulouValavani, E. “DNA examination of ancient dental pulp incriminates typhoid fever as a probable cause of the Plague of Athens.” International Journal of Infectious Diseases 10 (2004): 206–214. Pappas, G., Kiriaze I. J., Giannakis P. and Falagas M. E. “Psychological consequences of infectious diseases.” Clinical Microbiology and Infection 15, no. 8 (2009): 743 – 747. Powell, C. A Philological, Epidemiological and Clinical Analysis of the Plague of Athens. John Carroll University Press, 2013. Thucydides. The Peloponnesian War, edited by B. Jowett. Oxford Claredon Press. Walters, K. R. “Perikles’ Citizenship Law.” Classical Antiquity 2 (1983): 314 – 336.

How Manifest Destiny Fuelled Racial Prejudice The Sovereignty Pandemic, the Paris Peace Conference, and the Contestation of National Space

Geography, edited by Stuart Elden, 223- the Cure of the Plague, as for Preventing 244. Abingdon: Routledge, 2007. the Infection. Edinburgh, 1721 in Royal Heffernan, Michael. “The Politics of the College of Physicians of London, Map in the Early Twentieth Century.” Eighteenth Century Collections Online, Cartography and Geographic Information (Edinburgh: London, Printed 1665: and Re-Science 29, no. 3 (2002), 207-226. printed at Edinburgh, 1721). Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. ‘Bring out your dead,’ Back to Blog: Mercat London: Wiley-Blackwell, 1991. Tours, 19 February, 2016. https://www.Legg, Stephen. “An International anomaly? mercattours.com/blog-post/bring-out-your-Sovereignty, the League of Nations and dead [Accessed 19/02/2020].India’s princely geographies.” Journal of Historical Geography 43 (2014), 96-110. Racialised Disease: The Bubonic Pinder, David. “Mapping worlds: cartography Plague in Honolulu, 1899-1900and the politics of representation.” In Abbot, Carl. “The ‘Chinese Flu’ Is Part of Cultural Geography in Practice, edited a Long History of Racializing Disease.” by Alison Blunt, Pyrs Gruffudd, Jon May, Bloomberg CityLab (2020). Accessed 28 Miles Ogborn, and David Pinder, 172-187. November 2020. https://www.bloomberg.London: Routledge, 2003. com/news/articles/2020-03-17/whenSeegel, Steve. Map Men. Transnational racism-and-disease-spread-together Lives and Deaths of Geographers in the Echenberg, Myron. “Pestis Redux: The Making of East Central Europe. Chicago: Initial Years of the Third Bubonic Plague University of Chicago Press, 2018. Pandemic, 1894-1901.” Journal of World Smith, Leonard V. Sovereignty at the Paris History 13, no. 2 (2002): 429-49. Peace Conference of 1919. Oxford: Oxford Frith, John. “The History of Plague – Part University Press, 2018. 1. The Three Great Pandemics.” Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health 20, no.2 The Sand Creek Massacre and the Death (2012). of Native American Culture Ikeda, James K. “A Brief History of the Brown, Dee. Bury My Heart at Wounded Bubonic Plague in Hawaii.” Proceedings, Knee: An Indian History of the American Hawaiian Entomological Society 25 (1985): West. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 75-81. 1970. Iwamoto, Lana. “The Plague and Fire of Horwitz, Tony. ‘The Horrific Sand Creek 1899-1900 in Honolulu.” Hawaii Historical Massacre Will Be Forgotten No More’. Review 2, no. 8 (1967): 379-393. 2014. Accessed: 22 November 2020 Mohr, James C. “Lessons for the https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/ coronavirus from the 1899 Honolulu horrific-sand-creek-massacre-will-be- plague.” Oxford University Press Blog forgotten-no-more-180953403/ (2020). Accessed 28 November 2020. “Kill the Indian, and Save the Man”: https://blog.oup.com/2020/03/lessons-for-Capt. Richard H. Pratt on the Education the-coronavirus-from-the-1899-honoluluof Native American http://historymatters. plague/ gmu.edu/d/4929/ accessed 22/11/20 Mohr, James C. Plague and Fire. (Oxford: citing Richard H. Pratt, “The Advantages Oxford University Press, 2006). of Mingling Indians with Whites,” Richter, Charles and Emrich, John S Americanizing the American Indians: “How Honolulu’s Chinatown ‘Went Up Writings by the “Friends of the Indian” in Smoke’” The American Association 1880–1900 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard of Immunologists, (2020). Accessed 28 University Press, 1973), 260–271. November 2020. https://www.aai.org/ About/History/History-Articles-Keep-for-Edinburgh’s Infrastructure, the Spread Hierarchy/How-Honolulu’s-Chinatown-of Disease and the Plague Outbreak of Went-Up-in-Smoke-The-Fi 1645 Tansey, Tilli. “Rats and racism: a tale of Allen, Aaron, and Spence, Cathryn. US plague.” Nature 568, no. 7753 (2019): “Edinburgh Housemails Taxation Book, 454-455. 1634-1636”. Woodbridge: Scottish History Society, 2014. Plague in Bombay in the Late 19th Chambers, Robert. ‘TRADITIONS OF THE Century: When Colonial Medicine gets PLAGUE IN EDINBURGH.’ The Edinburgh Political and Politics Meets the People Literary Journal, Or, Weekly Register of Primary: Gatacre, W. F. Report on Criticism and Belles Letters, no. 29 (1829): the Bubonic Plague in Bombay : By 415-16. W.F. Gatacre, Chairman of the Plague Davies, Gareth. ‘Edinburgh’s Plague Committee, 1896-97. (Bombay: Times of Laws,’ Edinburgh Expert Walking Tours India, 1897), Available at the University of - Blog, 17 November, 2015. https://www. Edinburgh Centre for Research Collections edinburghexpert.com/blog/edinburghs- Couchman, Malcolm Edward. Account plague-laws [Accessed 19/02/2020]. of Plague Administration in the Bombay Grierson, Flora. Haunting Edinburgh. Presidency from September 1896 till Edinburgh: R & R Clark, 1929. May 1897 (Bombay: Government Central Harrison, Mark. Disease and the Modern Press, 1897) Available at the University of World: 1500 to the Present Day. Cambridge: Edinburgh Centre for Research Collections Polity Press, 2004. Secondary: Michael, Worboys, “Colonial McLean, David. ‘Lost Edinburgh: The Medicine.” In Companion to Medicine in Great Plague of 1645,’ The Scotsman, 24 the Twentieth Century edited by Roger March, 2014. https://www.scotsman.com/ Cooter, and John V. Pickstone. (London; news-2-15012/lost-edinburgh-the-great- New York: Routledge, 2003) pp.67-79 plague-of-1645-1-3351337 [Accessed Michael Worboys, “Germs, Malaria and 19/02/2020]. the Invention of Mansonian Tropical Perfect, Hugh. “The Canongate.” (2019) Medicine: From ‘Diseases in the Tropics’ https://www.ed.ac.uk/education/about- to ‘Tropical Diseases” in Warm climates Image: The map made by Romer showing us/maps-estates-history/estates/the- and western medicine: the emergence of the border between Poland and Russia in canongate [Accessed 19/02/2020]. tropical medicine, 1500-1900 (Amsterdam: red, as agreed in 1920. Image sourced from Sir William Brereton, ‘A Visitor’s Impression Rodpoi, 1996) pp.181- 207 Pamięć Polski. The map is currently stored of Edinburgh, 6th June 1634,’ Scotland: David Arnold, Colonising the Body: State at Jagiellonian University Library in Cracow. The Autobiography: 2,000 Years of Scottish Medicine and Epidemic Disease in 19th [pamiecpolski.archiwa.gov.pl]. History by Those Who Saw It Happen ed. Century India, (Los Angeles: University of Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Rosemary Goring (Overlook Press, 2008), California Press, 1993) Communities: Reflections on the Origins pp.83-4. Mark Harrison, Public Health in British and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso, Convention of the Royal Burghs, ‘Proposal India: Anglo-Indian Preventive Medicine 1983. for Carrying Out Certain Public Works 1859-1914, (Cambridge: Cambridge Crampton, Jeremy W. “Maps, Race and in the City of Edinburgh,’ 1752 in Minto, University Press, 1994) Foucault: Eugenics and Territorialization Gilbert, Eighteenth Century Collections Mark Harrison, “Science and the British Following World War I.” In Space, Online, (Edinburgh, 1752). Empire”, Isis, 2005, Vol.96 (1) pp.56-63 Knowledge and Power: Foucault and Certain Necessary Directions, as Well for Deepak Kumar, Science and Empire,