7 minute read

Biking for the Best of Reasons

Deputy town supervisor of the town of Chili embarking on a 1,800 mile bike trip to raise money to three nonprofit organizations

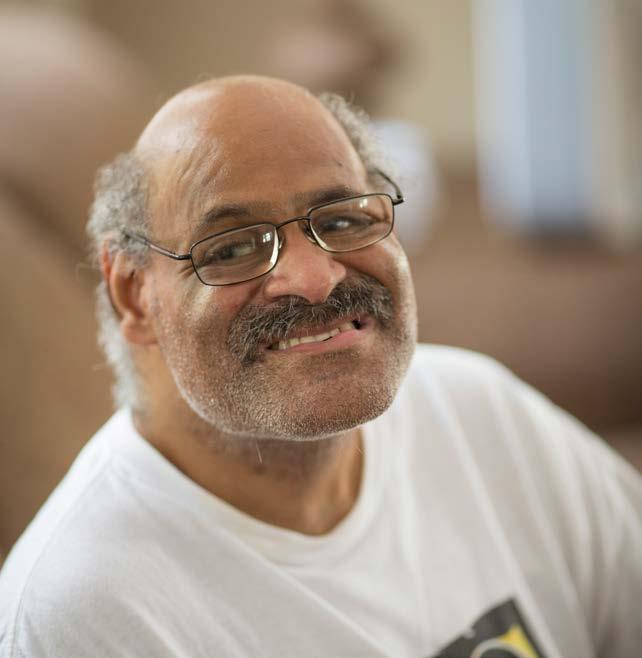

Michael Slattery just loves putting miles on his bicycles.

Advertisement

“I average about 5,000 miles a year,” says the deputy town supervisor of the town of Chili.

The married, 57-year-old grandfather plans to put his love for cycling to use for worthy causes on May 8, when he sets out on an over 1,800 mile jaunt down the Eastern Seaboard to raise money for three nonprofits.

The money Slattery brings in will go to the Pirate Toy Fund, the

By Mike Costanza

National Center for Missing and Exploited Children and Honor Flight Rochester.

Slattery plans to start his trip in Charlotte and head south, rolling through Penns ylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North and South Carolina and Georgia before ending up in Florida 25 days later. Along the way, he’ll stop at the Alexandria, Virginia headquarters of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) as part of his fundraising efforts.

NCMEC, the largest and most influential nonprofit child protection organization in the U.S., helps find missing children, strives to decrease child sexual exploitation and tries to prevent child victimization.

“We lead the fight to protect children, creating vital resources for them and the people who keep them safe,” says Edward Suk, executive director of NCMEC’s New York branch.

Slattery says the deaths of two young women, 20-year-old Fairport resident Lisa Eisman and 17-yearold Brittanee Drexel of Chili, made NCMEC’s fight particularly important to him. Both young women died violently.

Eisman was Slattery’s cousin. She and her college roommate, who were students at the State University College at Buffalo, were beaten to death in 1985 while hitchhiking to Fort Lauderdale on spring break. Drexel disappeared in 2009 while on a trip to Myrtle Beach. Slattery coached her for a time when she was on the team Chili Soccer.

“My daughters grew up with Brittanee,” he says. “For me, it’s personal.”

NCMEC aided the search for Drexel.

“We had our local and national case management team involved in cultivating leads with law enforcement,” Suk says. “We also handled targeted poster distribution, and media outreach through our media team.”

Raymond Moody, Drexel’s killer, was convicted of kidnapping, murder and first-degree sexual in late 2022. He was sentenced to life in prison on one charge and 30 years each on the other two charges. Slattery plans to visit the place where Drexel’s remains were found while en route to Florida, and to visit NCMEC’s Washington offices as part of his fundraiser.

Slattery’s upcoming journey south is just one of the rides he’s taken to raise money for NCMEC. Just last year, he participated in The Ride for Missing Children, NCMEC’s annual fundraiser. Mounting his bike, he pedaled through Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, Utica and Albany, covering about 100 miles in each city.

Since 1995, the Pirate Toy Fund has headed to hospitals and other locations in the greater Rochester area to distribute new toys to needy children free of charge. As Slattery pedals along to raise money for the nonprofit, he’ll have a friend at his back—literally. Otto Harnischfeger, the Pirate Toy Fund’s executive director, will follow him down the road in an RV, providing aid.

“I can’t believe he’s doing it,” Harnischfeger says of his good friend. “I ride five minutes and I’m sore. I want to get off the bike.”

Harnischfeger has known the Slattery family since he became friends with Raymond Slattery, Michael’s father, when the two were on the Rochester Police Department.

“It’s a caring family, they really are,” Harnischfeger says.

The money Slattery raises on his long-distance ride should be welcome.

“Our first year we gave out 300 toys,” Harnischfeger says. “Last year, we gave out over 36,000 toys free of charge, all because of the good nature of the Rochester community.”

In addition to raising money for the Pirate Toy Fund, Slattery sits on the nonprofit’s board of directors.

Six times a year, about 60 veterans and their helpers, called “guardians,” head out of Rochester for a weekend in the nation’s capital, courtesy of Honor Flight Rochester.

“Honor Flight Rochester provides airplane trips for veterans to travel together to see their memorials in Washington DC to receive that long-delayed thank-you that they’d not received many years ago,” says Richard Stewart, the nonprofit’s president and CEO.

The trip to the nation’s capital in- cludes hotel accommodations, tours of the World War II, Korean War and Vietnam War memorials and other important sites and a gala dinner in honor of those who once served their country. The veterans travel free, but their guardians, who are usually fam ily members or friends, have to cover part of the cost of the trip.

Slattery says he plans to stop in Washington this May to accompany an Honor Flight Rochester group as it visits memorial sites. After that, he’ll have lunch with them and get back on his bike.

“I plan on leaving Washington in the early afternoon, so I can get in about 30 miles or so,’ Slattery says.

Honor Flight Rochester, an all-volunteer organization, spends about $500,000 a year on its services to veterans, and is supported by donations. Stewart says the nonprofit is able to cover its current costs, but will have to fund new trips to Wash ington in the future.

“We have a fly-list of 1,000 veter ans,” Stewart says. “If we don’t have money, we don’t fly.”

Slattery’s ride south is just his latest effort to help his community.

He has also raised money for other nonprofits, including Camp Good Days & Special Times, which offers residential camping programs and recreational and support activities to children who are affected by cancer or sickle cell anemia and their families. In addition, Slattery sits on the Chili Town Board.

“It’s a passion for me,” Slattery says. “I enjoy giving back.”

The father of two grown daugh ters and grandfather of four children recently retired from the Monroe County Department of Transportation, where he was the highway maintenance manager.

How to Donate

For more information about Slattery’s upcoming ride or do donate to his fundraiser, go to: michaelscharityride.com.

For more information on the nonprofits for which he plans to raise money, go to: www.missingkids.org/ footer/about/newyork, www. piratetoyfund.org or https://honorflightrochester.org.

Shortage: Attracting Nurses to the Bedside

By Deborah Jeanne Sergeant

The pandemic exacerbated the longstanding shortage of bedside nurses. Tougher conditions, supply scarcity, employee illnesses and many sicker patients prompted many hospital nurses to quit the profession or move into a non-hospital role in nursing.

In addition, waves of retiring nurses have also affected the number of hospital nurses, according to Lydia Rotondo, associate dean of education and student affairs at the University of Rochester School of Nursing.

“We have a lot of people aging out,” she said. “Most of our faculty are over 50, so there are fewer educators.”

To properly care for patients, many hospitals temporarily reduced capacity or paused services. Some are still not operating at full capacity, as that would place the patient-to-nurse ratio at unsafe levels. Some also use agencies dispatching travel nurses, which seems to Rotondo a bit like a “shell game,” shifting nurses from working for hospital systems to better-paying traveler positions. Some agencies pay four to five times what regular nurses receive.

“The financial piece is significant,” she said. “Team and culture and expense of orienting people is affected by travel nurses. That’s all part of it.”

A lack of nurses at long-term care facilities further worsens the problem, as sick people who need shortterm rehabilitation or long-term care have no place to go and must therefore stay at the hospital longer, filling beds needed by still sicker people.

“We have at any given time 100 ‘boarders,’” Rotondo said. “The lack of ability to get people out of acute care and into LTC over stresses every hospital.”

Rotondo can’t blame people who turn to lucrative travel nursing to pay off school debt. But she added that the tide is beginning to change as students interested in nursing realize that many organizations offer education benefits.

Representing another factor, nursing school applications are down 6 to 7% and Lisa Kitko, dean of the University of Rochester School of Nursing, is not sure why, although she theorizes that the uptick of people applying during the pandemic’s acute period has leveled out once people fully realized the challenges of the work.

She believes that hospital nursing recruitment and retention requires extra creativity.

“Early in the pandemic, we offered a traveling position to our own employees without benefits,” Kitko said. “Salary needs to come down to a happy medium between travelers and the pre-COVID rates.”

Many healthcare organizations are grappling with payrates, as many travelers have been receiving four to five times the rates of non-travelers. But engaging traveling nurses is not ideal for many reasons.

“Right now, obviously, we have to use agencies more than we’d like to,” said Kara Silkiewicz, talent acquisition supervisor and human resources for Finger Lakes Health. Although they can fill in the gaps, travelers cost more to employ, both through higher administrative overhead and higher wages, and do not tend to contribute to camaraderie and continuity of care with regular nurses. But Silkiewicz said that Finger Lakes Health is working to draw on new nursing program graduates with the lure of tuition reimbursement.

Like many other organizations, Finger Lakes Health also tries to “grow its own” nurses by hiring high school students for entry level nutritional services positions. When they graduate, they can enter the CNA program, then move on to the LPN school and eventually RN education.

Finger Lakes Health also works to hire mid-career job seekers, using social media now more than job fairs, which Silkiewicz said “aren’t as effective anymore. It’s instant now. People want to click and apply and converse through text message.”

Kathy Mills, dean of the college of nursing at Finger Lakes Health College of Nursing & Health Sciences, wants to see New York State allow simulation hours to account for onethird of RNs’ 600 required clinical hours.

“That will open up clinical spots to get students in,” she said. “Right now, it’s bottlenecked. I can only put so many students through. More nurses will be able to be accepted into a program this way.”