22 minute read

REGIONAL ROUNDUP

For Innovation Report 2020 we decided to take a closer look at Mississippi’s four major research universities—the University of Mississippi, Mississippi State University, Jackson State University, and the University of Southern Mississippi—and the innovation ecosystem around each. What we found was surprising and intriguing.

In two cases—UM and USM—there’s a new partnership initiative aimed at making the school and community more responsive to entrepreneurial needs.

Advertisement

In Oxford, it’s the “Delta Force” which includes both on-campus and municipal leaders looking at ways to build businesses in the area. At USM, it’s “The Hatchery,” an efort spearheaded by the Trent Lott National Center to better focus a variety of university resources—from the Pine Belt down to the Marine Research Center on the Gulf Coast—on economic development and entrepreneurship.

At MSU and JSU, new maker spaces are the centerpiece of efforts to bring students, faculty, and community together to prototype new ideas and breed innovation.

And partnerships abound, as well. Allyson Best, director of the Department of Technology Commercialization at Ole Miss mentioned three:

JSU is helping UM bring the I-Corps program to its campus.

UM has a partnership with JSU to work with eight other states for funds and mentors for biomedical startups.

UM and MSU are part of the XOR partnership among SEC schools to fnd CEOs for startups from within the pool of alumni from Southeastern Conference schools.

Read on for a look at four diferent parts of the state and how entrepreneurship, higher education, and economic development are putting startup businesses and public-private partnerships front-and-center in 2020.

STARKVILLE

Jefrey Rupp is still pretty much a mayor. Once the elected mayor of Columbus, Miss., Rupp is now the director of outreach for the Mississippi State University College of Business. But when he tours you around Starkville, he’s just as likely to talk about “mayor” stuf as “college” stuf.

Just ask him about “Pumpkinpalooza” in downtown Starkville in the fall of 2019. In front of the Idea Shop, a project of the university’s business school, Rupp spearheaded the inaugural “Talledegourd 500.” Participants used Idea Shop tools to add “two axles and four wheels” to their pumpkins. They then raced the pumpkins down a big ramp built in the street.

Talledegourd 500

“Hundreds of people were watching. You should have seen the pumpkin carnage,” he laughed. “Next year, it’s a ‘thing.’ The part of me that is a former mayor loves this stuff.”

The Idea Shop is a storefront and maker space in downtown Starkville that is run by the MSU Center for Entrepreneurship and Outreach, or E-Center, where Rupp has his ofce. Members of the Idea Shop have access to the Turner A. Wingo Maker Studio, which features tools for woodworking, electronics, laser engraving, and 3-D printing. Idea Shop members can also display and sell their products to the general public in the storefront.

The Idea Shop

Membership in the Idea Shop is open to students, MSU employees, and the general public. Newcomers can take workshops to get acquainted with the tools.

“We have over 90 paying community members of the Idea Shop,” said Rupp. “We’re looking at adding another building downtown.”

Rupp calls the overall idea that the university is pursuing “blurring the line between ‘town and gown.’” By investing in the town, the university improves the quality of life for everyone who lives in it. As the quality of life improves, more students and faculty decide to keep their startup businesses in Starkville.

So far, the plan is working. At the Greater Starkville Chamber Partnership in downtown Starkville, student and former-student companies have low-cost offices away from campus, with shared reception and conference facilities. As a result, those young companies remain a part of the entrepreneurial ecosystem represented by the blending of the university’s resources with the city and county economic development efforts.

“As a company and as individuals, we’ve been given nothing but support, encouragement, and enthusiasm from the Starkville community in our journey to grow and thrive,” said Rahul Gopal, CEO of student-founded CampusKnot. “The proximity to the university has helped us understand our goal of classroom engagement even better with the cooperation of educators and students.”

Just down the street from the main downtown strip, Glo, another student-founded company behind Glo Cubes and Glo Pals, has a charming, porch-wrapped headquarters for its burgeoning empire.

The company, which just announced a partnership with Sesame Street for its Glo Pals products, overfowed with boxes from its Black Friday orders when we visited in December 2019.

GloPals from Vibe LLC

“I don’t think Glo would still be around had we not stayed in Starkville. Having such a close association with the talent at Mississippi State has allowed us to grow incredibly quickly, while also fostering amazing community support,” said Hagan Walker, CEO of Glo. “I feel like everyone in Starkville has rallied around us, and it truly has allowed us to continue to grow and to give back.”

The hub of all this innovation activity is on campus, at the MSU E-Center, inside the business school. Glass walls covered in dry-erase marker divide conference rooms from offices and open collaboration space.

On the day we visited, the student entrepreneurs behind DueT Technology sat around a table and told us their story. DueTT has developed a new type of electric clippers for barbers, specifically aimed at African American and Latino barbers. Rupp said later that DueTT, which has funding from the Bulldog Angel Network, would soon be moving into a new office in downtown Starkville.

“A large percentage of Mississippi State’s students are frst-generation college students,” said Eric Hill, director of the E-Center. “Getting any student to start a business—and believe they can do it—depends on how well we deliver the message that MSU is the place for entrepreneurial ventures.”

The MSU E-Center

Students or faculty can make use of the E-Center, where the core offering is MSU VentureCatalyst. The curriculum helps prospective entrepreneurs build their business plan, test their product ideas, and learn to pitch their company to investors. Along the way, entrepreneurs can raise up to $7500 by reaching predefined benchmarks.

MSU eCenter

Many of the businesses that succeed in the E-Center go on to pitch the Bulldog Angel Network, which focuses on funding high-growth businesses started by MSU alumni. Hill says that in FY2018, over 100 companies went through the program, raising over $600,000 in seed capital, mainly from the Mississippi Seed Fund and the Bulldog Angel Network. Many of those companies have remained in Mississippi; not a few of them are still in Starkville.

“Wins bring more wins,” Hill said. “We want our entrepreneurs to stay and set up shop here. We need to make it make sense for them. A $100,000 investment goes three times as far here. And when you have a huge order, our team will come and help you stuf boxes.”

Hill notes that there are now fve successful student startups in downtown Starkville, which shows student entrepreneurs that success is attainable. He credits the university’s leadership and Jefrey Rupp for embracing the town and gown philosophy.

“It’s going to be very exciting to see where things are in fve years,” Hill said.

OXFORD

Jon Maynard gets visibly excited when he talks about what he calls the “Delta Force.” It’s an ad-hoc group of people from the University of Mississippi and the economic development community in Oxford-Lafayette County who have been meeting over the past six months to talk about entrepreneurship and economic opportunities.

“In the past, there have been initiatives from the University that were more about plugging users into programs at the University,” said Maynard, the CEO and president of the Oxford-Lafayette County Economic Development Foundation. “Now, there’s a strong push to work strategically with of-campus partners. We’ve noticed that really growing in the past 12 months.”

With the full name “Entrepreneurial Delta Force,” there’s no doubt that these meetings have been a signifcant step to grow the entrepreneurial ecosystem in and around Oxford.

“Delta Force” members said repeatedly that there is strong support for entrepreneurial initiatives from the university’s highest levels of leadership.

“It seems like there’s been a new push from the top, from the university, especially from Provost Noel Wilkin, to empower their folks to go out and accomplish things for economic development and entrepreneurship,” said Allen Kurr, vice president of the Oxford-Lafayette County EDF.

Maynard says that the University of Mississippi’s new chancellor, Glenn Boyce, has said that he’s an innovator and is on board with fnding ways for the university to get out into the community to make things better.

“I’ve been at Ole Miss 25 years now, and I’ve never seen such a culture of cooperation and support for economic development and all that implies such as workforce development and partnership with industry,” said Allyson Best, director of the ofce of technology commercialization at UM.

Insight Park @ University of Mississippi.

What the economic developers hope is that this push from the university will lead to more jobs and growth in a community that is already economically strong. But with the university’s resources brought to bear on issues such as turning academic discoveries into products and companies, all the boats in the region could start rising. On the edge of campus, just down the street from the softball field, sits Insight Park, where several new projects are in the works. A big one is the expansion of the Catalyzing Entrepreneurship and Economic Development (CEED) program, to its new space in the facility, which will be a virtual reality lab installed by Jackson-based Lobaki.

CEED Students

CEED, run by Dr. J.R. Love out of the McLean Institute, offers scholarships to students to help them engage with business and community leaders in surrounding counties. The students gain both entrepreneurial and economic development experience, working on projects such as the James C. Kennedy Wellness Center in Charleston, Miss., where students served as interns while completing market research and surveys to determine the viability of the workout facilities and outreach programs for public health.

Insight Park will also soon be home to the new UM Biomedical Research Facility, complete with a cadaveric biomechanics lab, biomechanics testing lab, and co-working space (in separate areas, thankfully).

William Nicholas, director of economic development for the University of Mississippi, noted that the biomedical facility will support the medical device industry and productizing other innovations by faculty and students. After a trip to Memphis, where Nicholas and others learned that 41 medical device companies are headquartered, they realized Oxford was missing out in a big way.

“We believe the impact of the research center could be significant. If we begin to conduct research and testing in Oxford, it will attract startups as well as mature medical device companies. Nicholas said. “Regardless of whether we support a startup or attract an existing company, the economic impact over time could be notable.” When you talk to members of the “Delta Force,” the emphasis on enterprising faculty members and administrators comes up often. “Noel Wilkin, UM’s provost, takes the lead; Josh Gladden, vice chancellor for research; Allyson Best, director of the office of technology commercialization; Dave Puleo, dean of engineering; Matt O’Keefe, executive director of the Center for Manufacturing Excellence; Darren Van Pelt a recent addition to engineering did amazing things with SpaceX and Lockheed-Martin, and now he’s back at Ole Miss, Nicholas said. “This strong commitment from leadership trickles down to our faculty and students. Adam Jones in computer science teaches virtual reality enabling UM students to create original applications for VR and AR.”

Oxford is already known for several successful startups in the past decade or so, such as FNC, NextGear, mTrade. And the fow from university to the city and back is palpable. General Atomics moved from the Oxford Enterprise Center (a large barn of a business incubator where mTrade still has offices) to Insight Park, because of the close proximity to the National Center for Physical Acoustics.

“We work well together; they have diferent requirements of their tenants for them to move into Insight Park,” said Holly Kelly, executive director of North Mississippi Enterprise Initiative, which runs Oxford Enterprise Center. “When William (Nicholas) has somebody who pops up there, and he can’t fulfll what they need, he’ll send them to me.”

Maynard wants to see those shared spaces for businesses expand in Oxford, and has his eye on real estate in diferent parts of town where that could happen. Successful businesses sharing space with research facilities and startups could create synergies that beneft them all.

That’s one of the best outcomes possible from the “Delta Force”—networking and communication that makes it easier for entrepreneurs to fnd the resources they need on or of campus.

“It’s about building an ecosystem instead of just what one entrepreneur needs,” said Maynard, who, as an economic developer, is a critic of subsidizing large industrial relocations. “The real issue is helping startups answer the question ‘Is this a good idea or a bad idea?’”

That comes from all of the players in that ecosystem—the “Delta Force”—talking to one another. “It’s a continuum of diferent assets: idea generation, startup assistance, maker spaces, a database of talent,” Nicholas said. “And as we all work together, the solutions will become more apparent.”

HATTIESBURG & GULF COAST

“You don’t have glasses. Take these.” Dr. Monica Tisack, director of the Mississippi Polymer Institute, handed me a pair of plastic safety glasses and led the way into a secure lab where scientists test materials to see how they hold up under extreme temperatures.

“[Imagine a device] is going to go into space,” she said while pointing to a hulking Instron testing machine that scientists use to determine how materials change in diferent conditions. “What properties will it have when it gets really cold?”

From there we moved to the “wet lab” where chemists were hard at work checking instruments and jotting down notes. Beyond that, we entered another room with a human-scale “walk-in hood” and oversized stainless-steel chemistry equipment.

“You wouldn’t think it looks really special, but (the walk-in hood) is highly coveted in the world of scale-up,” she said. That day, it had been taken over by Chromis Technologies, a New Jersey-based company that came to Mississippi for some development work with MPI. The company eventually opened a permanent lab in the Accelerator, with plans to expand in 2020.

As we toured the Accelerator with Robbie Ingram, director of the Innovation and Commercialization Park, it became increasingly apparent that the Mississippi Polymer Institute is a big deal. Its capabilities and expertise draw private companies to Hattiesburg to set up labs for testing the materials in their products. Some then build production facilities for bringing innovative products to market and shipping them out. And MPI’s services are offered at relatively low cost, particularly for Mississippi companies, as they’re ultimately a part of the University of Southern Mississippi.

The Accelerator

The Accelerator sits on a 500-acre park where Ingram says over the next ten years he hopes there are ten or more new buildings, many of which could be research-driven companies or corporate R&D departments newly located in Mississippi. That’s a big piece of the strategy for USM and Hattiesburg economic development: Attract companies to Mississippi because of the polymer and materials expertise, and fnd ways to spin research out from the university into companies that locate on campus or close by.

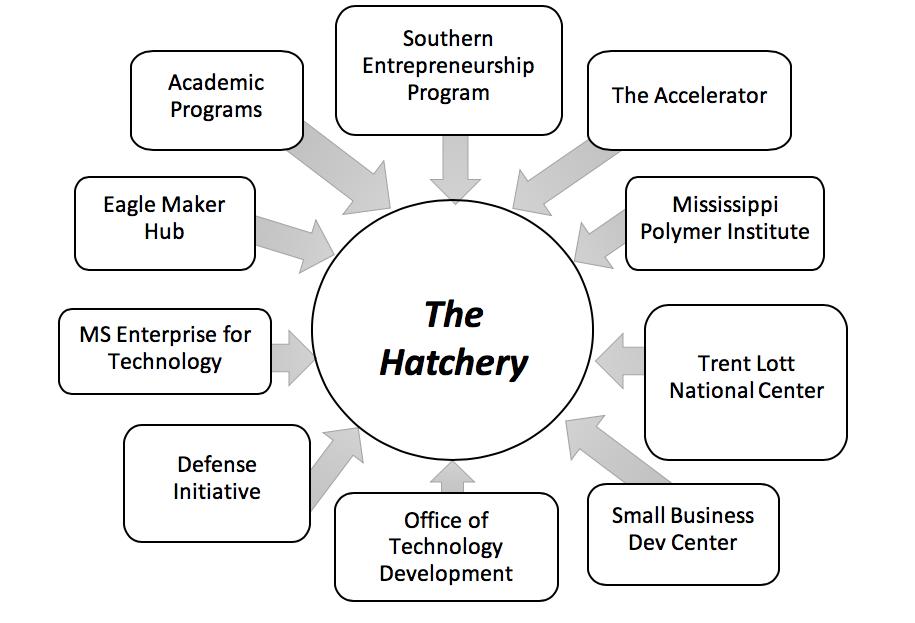

But that’s just one puzzle piece. Recently, an initiative called “The Hatchery” has sought to identify the other pieces—entrepreneurial and economic development resources on campus—and get them all working and thinking together.

“’The Hatchery’ is an internal title we use to describe the ways innovation can happen with a research university. It’s how we connect faculty and the new technologies and innovations they’re discovering with product development—and even launching new businesses,” said Dr. Shannon Campbell, director of the Trent Lott National Center for Economic Development and Entrepreneurship. “We are also encouraging our students to think more entrepreneurially as they’re going through the diferent programs they’re studying.”

The Trent Lott National Center is celebrating 40 years of ofering an advanced degree in economic development, and Campbell said it’s one of the few degree programs of its kind in the country. That also makes the Lott Center a logical “hub” for connecting USM’s research expertise with the companies that need those services.

“We look for ways to connect with industry sectors and business needs so that what we’re working on is relevant for job growth and business growth,” she said. “It brings more value to the companies and the university when we can partner.”

Along with the Mississippi Polymer Institute, another example of that public-private outreach is the Marine Research Center at the Port of Gulfport on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. USM designed the MRC specifcally to work with private companies or organizations such as the U.S. Navy or the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association. The goal is to create a space for prototyping and testing devices or products that happens closer to real-world applications.

“This isn’t necessarily bench-type research. It’s late-stage development,” Campbell said. “It’s very appealing to be able to walk out the back door, launch those devices, and be able to test them in the bay area of the Port.”

Marine Research Center

A second facility, the Roger F. Wicker Center for Ocean Enterprise, is under construction now at the Port.

Eagle Maker Hub

Back on campus in Hattiesburg, the Eagle Maker Hub is a 3000-square foot maker space in the student union. It opened in 2016, and it was the first publicly available maker space offered by a Mississippi university. While its array of 3D printers, laser cutters and woodworking tools are different from the tools available at MPI, in a way, the mission is similar—finding ways to make research and science accessible and practical for USM students and faculty.

“Since I’m a teacher-educator, I focus on our future teachers being able to use this technology in their classrooms,” said Dr. Anna Wan, director of the Eagle Maker Hub. “Most of the schools out there have this technology; it’s just the math and science teachers don’t have access to it.”

Wan, a mathematics professor, travels the state working with secondary education professionals to help them integrate hands-on prototyping tools into K-12 curricula to make learning more fun and relevant.

“When I told [USM] my research was integrating this kind of technology in teaching K-12, the university put money behind that,” Wan said, when telling the story of being recruited to the university. “I felt very welcomed by that.”

Ingram lists the USM departments and projects that comprise the Hatchery: Mississippi Polymer Institute; Eagle Maker Hub; the School of Ocean Science and Engineering. He also name-checks Dr. Brian Cuevas in the Ofce of Technology Development, Dr. James Wilcox of the Center for Economic and Entrepreneurship Education, and Dr. Campbell at the Trent Lott National Center. Plus, there’s the Southern Entrepreneurship Program for teaching startup basics to Mississippi’s youth. And USM’s course “Hacking for Defense” is an initiative with the Department of Defense that exposes students to lean startup principles as they seek to build tools for military and frst responder applications.

Given all those components now working more closely together than ever, Ingram predicts success. “I think when you come back to do this report in ten years, it’s going to be a much more dynamic and robust entrepreneurial and innovative ecosystem,” he said.

“I’ve been here three years; I worked in industry for 20 years before that,” Tisack said while we sat in the Accelerator after our tour of MPI. “And what’s attractive is that it’s so diferent from most of the places I’ve been. I realized that here’s a good chance to make a diference.” Campbell says she hopes the Hatchery improves outcomes for students and faculty over the next decade.

“We have more students coming out who have not just core knowledge in particular programs, but they’ve learned from an entrepreneurial perspective how to be a better employee or even own their own business,” said Campbell.

“And helping faculty members think about how something could be applicable in business and valuable to society—that’s an innovation,” she said. “Helping faculty get exposure to the concepts of entrepreneurialism broadens their perspective.”

JACKSON

Get a tour from Dr. Almesha Campbell of the new Center for Innovation at Jackson State University, and it’s easy to believe she had a busy 2019. The Center, located on the second floor of H.T. Sampson Library, had a formal opening in January of 2020. It includes a virtual-reality lab; 3D printers; computers for graphic design work, 3D modeling and sofware development; machines for textiles and button-making; reconfigurable lecture space, and small rooms for entrepreneurial breakout sessions.

As director of technology transfer and commercialization for Jackson State University, Campbell realized a few years ago that the role of “tech transfer” was changing. Traditionally, universities have helped faculty or employees license or otherwise monetize the intellectual property they create through discoveries and inventions. But Campbell sees that role as evolving. “I’ve been doing tech transfer and commercialization for about ten years, and then began moving into the entrepreneurial space because... tech transfer has changed,” Campbell said. “We are now expected to take you through the entire process of commercialization. Traditionally, we would do licensing, but now we are expected to get these startups going, teach them entrepreneurship, and help them fnd investors and industry partners.”

VR at JSU's Center for Innovation

Campbell said when she started with the university, the focus was on faculty-driven licensing and businesses. But now the university wants to help both student startups and established businesses outside of the university.

“I love dealing with students; I’ve seen how entrepreneurial they are and how they have all these ideas, but they don’t know what comes next.”

JSU has implemented the National Science Foundation’s I-Corps model, where a JSU student works with a STEM faculty member and a business mentor to test a science-driven idea for commercialization. The model requires a lot of customer interaction to validate potential product ideas, which Campbell says is good. But, in the past, students would have to go to the engineering school or other parts of campus for prototyping while meeting elsewhere to discuss building the business.

Instead, she liked the idea of ofering tools for prototyping and business-building in one central location: the Center for Innovation.

“A lot of this equipment was already on campus; they just had to go to a lot of diferent places to use it,” she said. “I’m bringing it all to a location that is more visible, more utilized, where students are trying to use all aspects of it to create a business. Then I’m here to help them with technology transfer, commercialization and entrepreneurship.” Along with prototyping and design equipment from other parts of campus, The Center for Innovation has a new VR lab installed by Lobaki, which has established labs at the University of Mississippi and Mississippi State University as well. Campbell said that one thing she likes about the VR lab—and encourages throughout the Center—is the fact the students in a variety of majors can engage with the equipment and accomplish things. “After taking some VR design courses myself, I realized I need art students; I need computer science students; I need engineers,” she said. “But I need marketing and journalism students, too, because I need them to help do some stuf in this space.” The Center has a small, soundproofed studio with a fully contained vlogging and podcasting system; Campbell sees journalism and marketing students using that equipment to help student startups communicate, market, and get the word out.

The Center pays a handful of student fellows to learn how to use all of the equipment and then help students, faculty, and community members who come to the center for product prototyping or other entrepreneurial support.

Campbell also expects the Center to be a resource for the community. In the basement of the library, she can ofer incubator space for local startup businesses, which can then take advantage of the 3D printers or other resources in the Center. She says that organizations such as Innovate Mississippi or The Bean Path can use the facilities for meetings or programming.

Campbell hopes to see some of her student startups qualify for Mississippi Seed Fund awards and national I-Corps funding, and would like to feed angel networks with good prospects.

For now, exposing students to the tools and principles of entrepreneurship is already rewarding. “At this point for the Center, success would be for the students to have this experience on their resumes,” she said.

Dr. Nashlie Sephus, the founder of The Bean Path, said the initial goal of her non-proft organization is something similar: helping regular people in Jackson gain exposure to technology. Sephus, who works for Amazon on artifcial intelligence initiatives, was part of a startup, PartPic, that sold to Amazon in 2016. A Jackson native, she spends a few days most months back in Jackson working on her non-proft and planning a new development in downtown Jackson that will be a live-work-play “Tech District.”

The Bean Path

The Bean Path, in 2019, helped over 200 people with their technology problems or challenges during volunteer-driven

“Ofce Hours” held once per month at a Hinds County library. While many of the people they are helping are senior citizens and lower-income citizens who need help with computing basics such as posting on social media or building a website, the Bean Path’s volunteers help potential entrepreneurs from a variety of backgrounds as well.

“At least fve potential founders sought guidance, and four of those have formed companies and will soon launch apps,” Sephus said. She notes that simply giving people more exposure to technology can empower them to come up with creative ideas.

“Our target is the people who you would least see in tech areas. What is simple to many people, others are afraid to tackle these things,” she said. “We can peel back those layers one-by-one. Eventually, you will see a community in the city of Jackson that embraces technology and tech entrepreneurship.”

Sephus said she’s excited about the Center for Innovation and hopes to continue working with Campbell on joint outreach and entrepreneurship opportunities.

“I think what she is doing is pretty amazing. A lot of companies get business advice but not technical guidance,” she said. “Creating that safe space is what she’s doing and what the Bean Path is all about.”