8 minute read

MARTIN SCORSESE

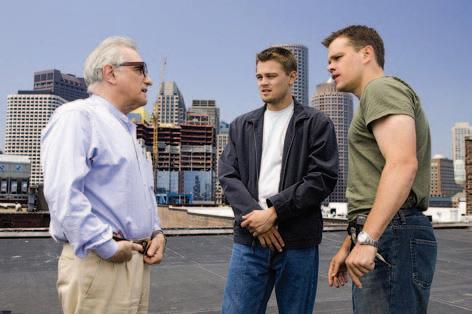

FILM INTERVIEW MARTIN SCORSESE Still Edgy After All These Years

ITH EIGHT OSCAR nominations over the past 27 years, few directors have enjoyed more critical acclaim over the course of their ca reers than Martin Scorsese. Born in Queens, NY in 1942, Scorsese emerged as a maverick filmmaker during the same ‘70s Hollywood heyday that produced George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, with early works such as Taxi Driver and Raging Bull becoming cultural touchstones for generations to come. But perhaps what’s most impressive is the fact that the diminutive Italian doesn’t seem to be getting any softer with age. Inspired by his ongoing creative partnership with Leonardo Di Caprio, Scorsese’s last three films have earned a combined 26 Oscar nominations, while documentaries such as No Direction Home: Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones’ Shine A Light gave him even more aging hipster cred. And with four films listed in development on the Internet Movie Database, Scorsese doesn’t appear to be in danger of slowing down any time soon. We recently spoke with the esteemed film legend on subjects ranging from his early career and working with Robert DeNiro to finally winning an Oscar for The Departed and his place in the annals of film history. W BY BRET LOVE

Advertisement

You’ve made numerous films about the criminal underworld over the course of your career. How did you originally become fasci nated with the subject? My father was born in 1913 in the New York tenements, and he became acutely aware of the struggles of being an Italian immigrant. He worked for Con-Edison digging ditches until he got his own grocery store, trying to provide for his working class family. But he knew there were organized crime elements around him, and it permeated the world in which he lived. It affected the lives of everyone in my family because they weren’t educated, so they had to live with this ele ment.

Have you ever had any concern that the ex treme violence at the heart of many of your films might ultimately limit your audience? Not really. That’s why we have an R rating. In some cases I’ve trimmed more of the violence to get the film the way I want it AFTER getting an R rating. But when you’re depicting a violent world, you have to be true to it, though in recent years I’ve tried to do it less graphically [than in the past]. I can certainly look at the movies I’ve made and know that I don’t have to prove I can do violence. (Laughs) Now I try to do most of it through editing, sound effects and the implication of violence so that you never see it graphically. I don’t know, maybe it might put some people off from seeing my films, but I hope it doesn’t. You made some of your best films with Robert DeNiro. What was it about him that made the two of you such a greatteam? Back in the ‘70s, we found that we shared a similar sensibility. Not only about work, but about life and about people. That just made it easier to work with him. We had the same taste, not so much in movies, but in the result. We never discussed these things directly. We always talked more about the truthfulness of what we were trying to get in a scene. In the ‘70s, the combination of him as an actor and myself as the director made it possible for us to get risky films like Taxi Driver and Raging Bull made. I don’t know if I could’ve gotten Taxi Driver made without him, and I certainly wouldn’t have been involved with Raging Bull, because that came from him. After King Of comedy we stopped, because we felt we’d gone as far as we could. Now it seems you’ve got that same sort of partnership with Leonardo DiCaprio, with Shutter Island filming now and the Teddy Roosevelt project after that.

I feel a great emotional and intellectual connection with Leo’s sensitivity as an actor, and we work well together to find the truth of how a character would react to a situation. It’s funny, because I’m in my sixties now and have had the luck to team up with actors like DeNiro and Daniel Day Lewis. So it was extraordinary to come across an actor like Leo, who has similar drive, a similar sense of honesty, likes my pictures, likes the same movies I like and totally gets them. I can show him a film like The Bicycle Thief and it knocks his socks off. To find that again in a young person and be able to do multiple pictures with him, and get that dedication and new energy in front of the lens is a real fortunate event. that I grew up on– were Irish filmmakers. We Italians felt very close to the family culture of the Irish. There were some differences when they first moved into the same neighborhood, but Irish literature is very important to me. The poetry of the Irish is extraordinary, and the Irish sense of Catholicism is a very interesting contrast to the Italian sense of Catholicism. Those are just my personal reasons. Major studios seem to be taking more chances on edgy young filmmakers. How do you feel about today’s crop of maverick di rectors, and do you see any similarities with your generation? I certainly do, but I’d like see more people like Wes Anderson, Paul Thomas Anderson and Spike Jonze getting the backing of a studio for a personal vision. You have to cater to the box office, because you gotta let people know what’s there, and to let people know what’s there it’s usually good to get a big movie star. They’re the vessel in front of the lens, and you have to live the movie through the persona of the actors. That’s great, but the danger is that you need actors who are not afraid to take chances. If they’re making too much money and you get a young director who wants to make a film with some edge to it, the actor may have a say in that, which could dilute the final product. In the ‘70s, there was no dilution. We all took a lot of chances with a lot of money, and hope fully that’ll be the next step for these young filmmakers.

I’M LEARNING NOW. FROM

THE SIZE O F THE FRAME AND THE C LOSE-UPS TO THE ENERGY AND PACING O F THE

EDITING, IT’S A LMOST AS

With films like Gangs of New York and The Departed, you seem to be focusing more on Irish storytelling than Italian in the last few years. That’s an interesting point. I’ve always felt a close affinity for the Irish, particularly coming out of the same area of New York City, even though by the 1920s-1930s most of the Irish had moved out of that neighborhood. I have a very strong love for Hollywood cinema, and some of the greatest filmmakers that have come out of Hollywood– some of the films

Did getting robbed of numerous Best Direc tor Oscars over the years give your win for The Departed a feeling of vindication?

I don’t know, it probably is better that I didn’t win in the ‘70s or ‘80s. When you’re young and do five or six pictures in a row that tell the stories you want to tell, you think maybe you should have won the Oscar. But after Raging Bull I never had a problem with the trade-off. I didn’t win any Oscars, but I got to work with interesting actors and producers and make some really interesting films. I felt like I got away with something! (Laughs)

As a respected film historian, are you able to step outside yourself to judge your place in the pantheon of great filmmakers? That’s a good question. I consider myself more a film lover than a film historian. I like films too much to be a critic of them. But as the years go by, when people say, “Oh Marty, this is an extraordinary work!” I say, “You haven’t seen as many films as I have.” I know where the levels are, and as far as I’m concerned I just do the best I can. When I gauge myself in my mind against the filmmakers I admire, there’s no way I can compete.

Do you feel like you’ve gotten any less edgy with age?

I’m a somewhat different person, but still basically the same. IfI took every second of the day to be incensed or get riled up like I used to, I wouldn’t make it through. I do still feel the same passion for the craft, but the question is, what am I to learn from the craft now? It’s a real challenge, because I don’t wanna get bored doing the same things I’ve always done. But on the other hand, why turn the camera upside down when every director can do that? If the camera doesn’t have to move, don’t move it. That simplicity is what I’m learning now. From the size of the frame and the close-ups to the energy and pacing of the editing, it’s almost as if my entire slate has been wiped clean and I’m starting all over again. It’s really a scary proposition, because you don’t know if you have it anymore. How to tell a story with pictures is frighteningly challenging.