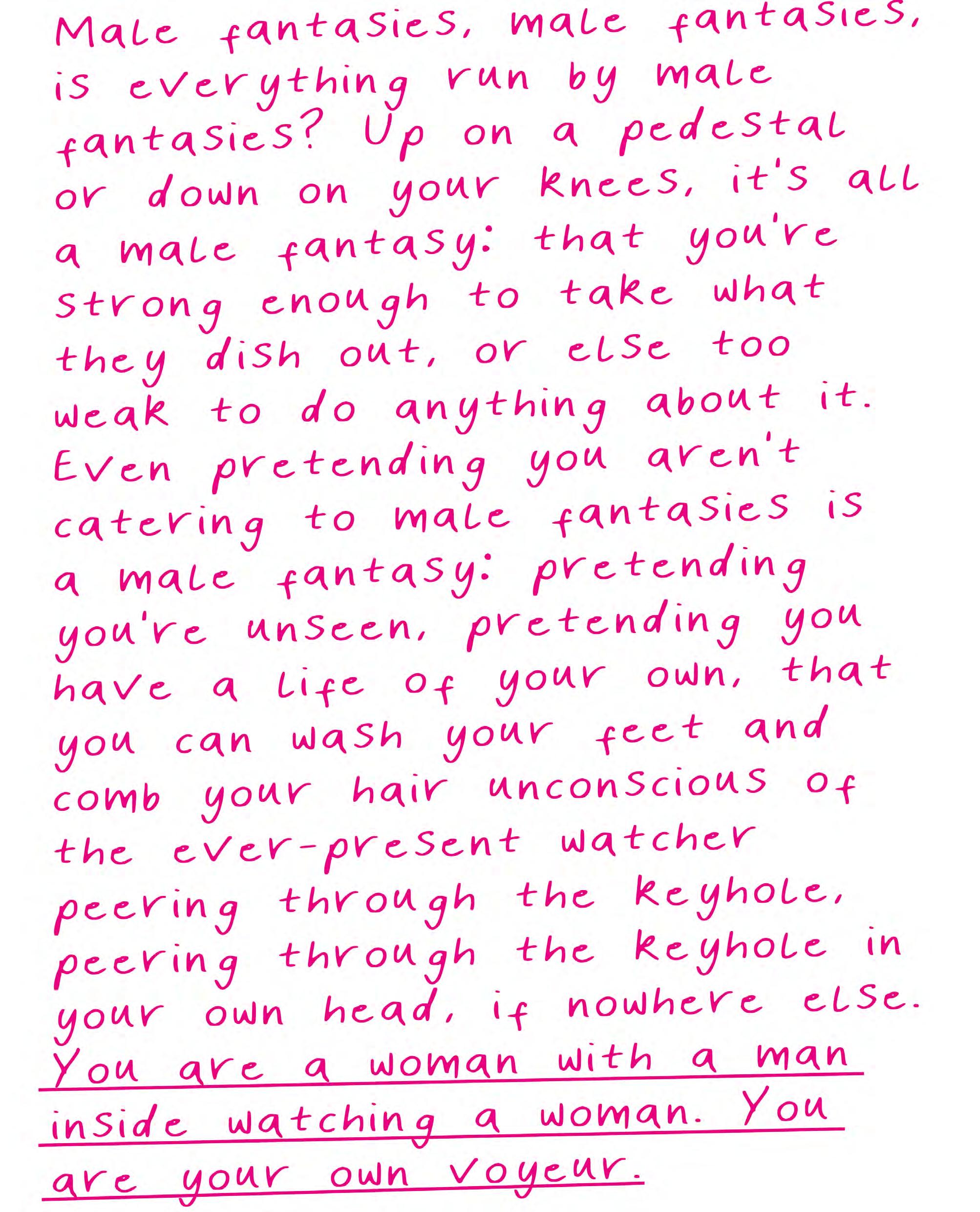

From being disguised in the murky depths of the supply chain manufacturing garments for next to nothing, being restricted by the ‘glass runway’ in corporations, to being valued based on the nature of their clothing, women are feeling the effects of gender inequality from all sides of clothes production.

This magazine, through a medium women have used to communicate for centuries, aims to shed light on some of this misogyny still guiding the fashion industry.

Brands thrive in the disconnect between garment workers and us as it enables them to reduce production costs, benefiting owners and fashion purchasers at the expense of employees. They withhold information about the realities of the garment supply chain, in order to guarantee a market for cheap clothing which adapts seamlessly to micro-trends.

No one wants to buy a shirt knowing that it has been sewn by someone for a fraction of their supposed minimum wage, nor a dress handembroidered by another who faces daily harassment and unsafe working conditions. By revealing this information, the fast fashion model that relies on cheap, unsafe labour would certainly collapse. Companies like Zara and Nike are at the very centre of the industry, where placing profits above human rights is a given. This lack of transparency impacts our ability to make informed choices about the clothes we buy, and inadvertently funds the continued exploitation of workers.

After all, keeping the problem hidden negates the possibility for any real accountability.

According to the International Labour Organisation, in some regions, nearly 80% of garment workers are women.

This is not a coincidence. Women’s integration into the initial stages of garment development has played a crucial role in the streamlining of our industry. Factory owners have been exploiting women’s systematic disadvantages in society in order to establish a “cheaper, more docile” workforce.

Women in the Global South often earn less than their male counterparts, face promotion barriers, and are expected to balance paid work and unpaid domestic labour.

Some companies even require women to take a pregnancy test as part of the hiring process. Pregnant women or those who refuse to be tested are automatically dismissed, and those who remain are forced to sign a document confirming they will not start a family during their employment.

By subjecting themselves to these terrifying sexist practices, these women are inadvertently reproducing it—but risk their livelihoods if they don’t.

It can feel empowering for women (especially from poorer backgrounds) to earn a salary to economically contribute to their families—and Naila Kabeer, a social economist, shows that garment workers tend to be more aware of their rights and are more critical about their treatment. This has led to many women creating and joining unions to demand safer working conditions, and better, more reliable wages, and has become a platform to demand responsibility from brands worldwide.

Women purchasing goods made with their earned money, as highlighted in Leslie T Chang’s Voices of China’s Workers TED talk, has also contributed to transforming societal norms and their perceived role. She also higlights the danger of “see[ing] workers as faceless masses, to imagine that we can know what they’re really thinking”—because we can’t. And that’s why it’s so important that we uplift their voices and listen, especially to those facing intersectional inequality, than risk drowning them out entirely.

The fashion industry relies heavily on women accepting and working minimum-wage jobs for its success. Women also spend upwards of three times more on clothing than men—and yet, they fill only 14% of the top executive positions at major brands. There are even fewer from ethnic minority backgrounds, meaning women of colour aiming for top roles in the industry are disadvantaged twice over.

The British Fashion Council’s 2022 report on diversity and inclusivity highlights how many businesses still hire based on ‘culture fit’ and prioritise previous experience from ‘aspirational’ brands. This means the industry’s talent pool is small and features similarly-minded people who reflect the traditional values of the sector. By employing a more diverse workforce, brands will be more likely to develop products and services that are actually inclusive and fit the needs of all people.

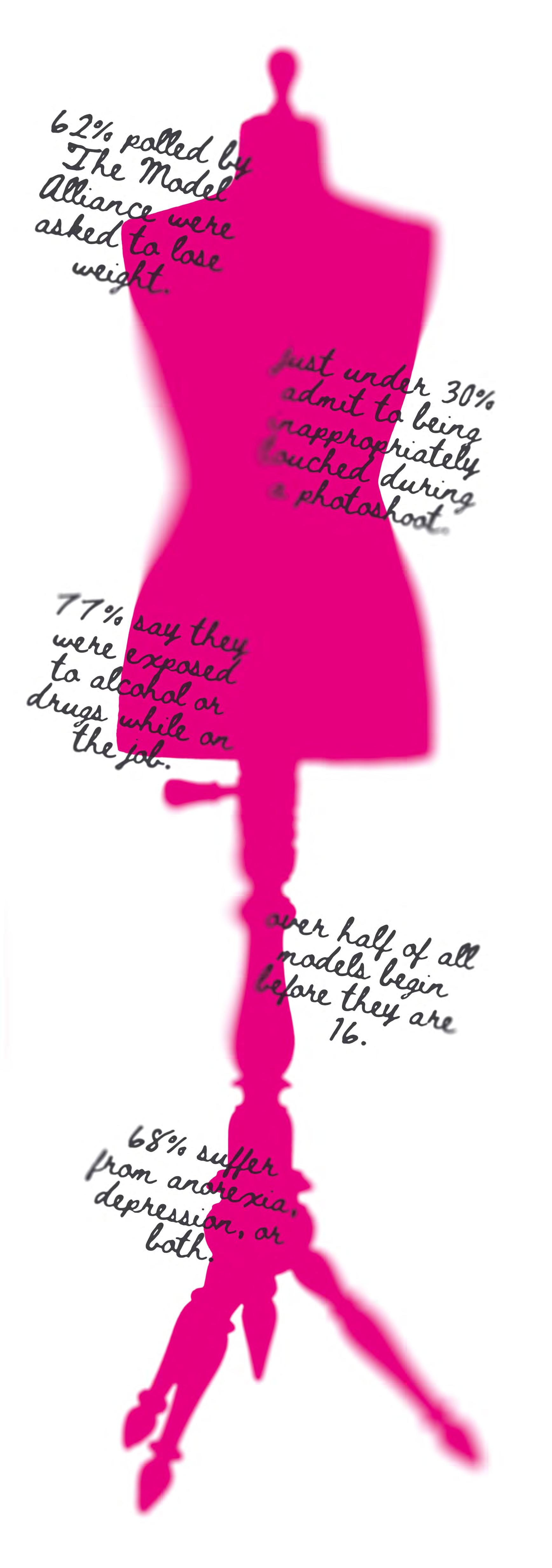

Modelling is another side of the industry which often subjects those it employs to sexual violence and exploitation, usually at the hands of their employers. Unregulated contracts in combination with the greed of fashion management companies and unequal power dynamics leave models with little control over their finances and well-being.

Esmeralda Seay-Reynolds, in conversation with

Variety, discusses how she was encouraged by her agent to stay catwalk-ready by swallowing cotton balls “to make [herself] feel full”. She also talks about the dangerous conditions she was required to model in, such as climbing near a glacier and jumping over 20-foot crevices, just for a photoshoot.