Overview of the delivery approach

Report produced for Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

14th August 2019- Draft Version 1.4

Robin Todd & Dan Waistell

Report produced for Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

14th August 2019- Draft Version 1.4

Robin Todd & Dan Waistell

To provide an assessment of the effectiveness of the ‘delivery approach’ in education in Africa and Asia through the development of several case studies which examine the strengths and limitations of various applications of the approach.

•

In recent years there has been growing interest across Governments, Multilateral and Bilateral Development Agencies in looking beyond the formulation of best practice policies and focusing on implementation and ‘getting things done’.

• At the heart of this interest has been a set of ideas and structures which can be termed the ‘delivery approach’. These ideas and structures are intended to bring about a transformative shift in attitudes and behavior towards public service delivery and achieve rapid results at scale by overcoming barriers to effective implementation, usually focused on government services such as health and education.

• The purpose of this assignment is to provide an assessment of the effectiveness of the ‘delivery approach’ in education, primarily in Africa and Asia, through the development of case studies which examine the strengths and limitations of various applications of the approach. This assessment took the form of a desk review of existing literature supplemented by face-to-face, phone interviews and emailed requests for information to individuals involved in the specific cases including government and district officials (including headteachers and teachers) facilitated through our in-country teams.

The first 3 sections of this report look at the ‘delivery approach’ as a whole, drawing lessons from existing research and practical experience. Section 4 lays out the specifics of delivery in certain locations through a series of case studies.

• Section 1 - Definition of the delivery approach, key principles and relationship to system strengthening

• Section 2 - Origins, evolution and variants of the delivery approach

• Section 3 - Impact of the delivery approach and assessment of its strengths, weaknesses and potential application in various contexts

• Section 4 - Country Case Studies

− Tanzania

− Sierra Leone

− Punjab, Pakistan

− Haryana, India

− Ethiopia

− Selected shorter case studies (PMDU UK, PEMANDU Malaysia, Indonesia, Colombia, Ghana)

Attempts to implement policies which improve education service delivery are often beset by challenges. Despite important contextual differences between countries there are a number of common public service delivery challenges which include:

• Lack of clarity as to the practical steps needed to turn national policy commitments into tangible outcomes at an institutional level i.e. within schools or colleges.

• Lack of joined up working at national level- policy priorities falling across or between various Councils, Boards or Agencies with unclear accountability for results.

• National level challenge to ensure quality of delivery when responsibility is devolved to local level. If results are poor in a local area, it is still often the national government which gets the blame for this.

• Focus in government on process and procedures rather than outcomes. This can lead to a limited sense of urgency to make a positive difference within schools.

• A lack of sufficient human and financial resources throughout the education system and a general sense of acceptance that these constraints mean that policy goals may never be achieved.

• Lack of local level understanding of national commitments means that intended results are never realised.

• Lack of understanding at the centre of government and among other stakeholders as to what is needed at an institutional level (school, college, etc.) to deliver high-quality services as well as lack of awareness of the day-to-day constraints faced by front-line professionals in delivering these services.

“I realised that the problems may not necessarily lie in the quality of policy making processes or policies themselves, but on the mechanisms in place for implementation, monitoring and evaluation. I noticed that much of the time we are bogged down by processes and bureaucratic inertia.”

President Jakaya Kikwete of Tanzania, opening remarks at the 12th Forum of Commonwealth Heads of African Public Service, 13th July 2015, Dar es Salaam

• In recent years there has been growing interest across Governments, Multilateral and Bilateral Development Agencies in looking beyond the formulation of best practice policies and focusing on implementation and ‘getting things done’. At the heart of this interest has been a set of ideas which can be termed the ‘delivery approach’.1

• The World Bank under the leadership of President Jim Yong Kim has played a role in advancing thinking on the delivery approach or what it terms the ‘science of delivery’. Dan Hymowitz from the Africa Governance Initiative (AGI) think-tank rightly points out that achieving results through this approach is as much of an ‘art’ as it is a ‘science’, requiring a shrewd understanding of politics and incentives.2

• The delivery approach involves the application of a set of best practice principles initially popularised in the early 2000s by the UK Government’s Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit (PMDU).

• These principles (set out overleaf) have evolved over the past two decades as they have been applied across numerous country and sectoral contexts with varying degrees of success. This evolution means that it has become quite difficult to define precisely what is meant by the ‘delivery approach’ as its application covers a range of strategies and techniques ranging from the very prescriptive, centralised and all-encompassing to the more flexible and localised application of specific tools or techniques.

• In summary the delivery approach consists of a set of tools and techniques which can assist in ‘getting things done’ but the application of these tools and the incentive structures and accountability mechanisms which surround them are absolutely critical. What works in one country, district or region will not necessarily be successful if rigidly applied elsewhere.

Through our involvement and observation of delivery approach processes in various countries we have identified the following key principles which are associated with the successful application of the approach, with consistent and active senior system leadership required across all principles.

Focus on a limited number of key priorities which are clearly understood across the delivery system. Ensure that there is a strong link between priorities and resources so adequate budgets are available.

Develop a clear understanding of tangible outcomes so that key priorities are viewed from the perspective of what is achieved at the level of the individual citizen e.g. in schools rather than what government spends or does at a Ministerial level.

Use regular data as the basis for establishing effective performance management routines. Develop good quality data and metrics to measure what matters. Collect reliable data for a small number of priorities and then ensure that data is analysed and used regularly to inform decision-making.

Engage stakeholders in analysing issues & owning outcomes. Involve front-line workers in analysing problems and developing solutions. Develop understanding of delivery systems to identify the drivers of successful outcomes and the motivations and perceptions of system actors. Develop a support and challenge function at national and local levels.

Develop a communications strategy to assist in rapidly engendering change and reform to reverse a perceived decline or deficit in standards of service delivery.

Ensure accountability for performance throughout the delivery system.

Strike the right balance between planning and delivery, recognising which areas can achieve rapid results and which may take a longer time.

To send a message throughout the delivery system that priorities are important , that progress and issues will be monitored and acted on regularly and that people at all levels of the delivery system will be held accountable for progress and results.

• None of the principles set out on the previous page are revelatory, complex or exceptional. These are common sense things which every Government should be looking to do in one form or another.

• In many countries however these principles are not being applied effectively or consistently. Thus, when looking to apply the delivery approach, countries should start from an assessment of their existing strengths and weaknesses. Building on existing strengths rather than focusing predominantly on weaknesses is an important part of the approach. It is also critical that any priorities, processes and structures are genuinely country-owned rather than imposed from outside.

• The aim of the delivery approach should be to strengthen existing systems so that they are better able to deliver citizen-centred outcomes rather than bypassing systems and establishing new delivery mechanisms- this may drive short-term results but runs the risk of making systems weaker over the medium and longer-term.

The delivery approach is not something completely new and actors in any education system are likely to have been applying some of the key principles in aspects of their work. What is different about the delivery approach is how the four principles come together in a coordinated, catalytic manner to address a specific problem or issue, focusing ‘like a laser’ until performance has improved. This ‘flow diagram’ of processes required to enable this to happen is set out opposite.

We have turned the delivery approach principles set out on Slide 4 into a set of hypotheses and statements on critical success factors. These are set out below and will be used as the framework to examine country case studies.

Critical Success

Factor 1: Senior system leadership & commitment

The delivery approach will not work unless there is a genuine desire from system leaders to achieve results and a willingness to devote significant time to ensuring that accountability flows through the delivery system. System leaders will usually be senior politicians but they can also be prominent public servants and will have genuine authority which is respected at local level.

Critical Success

Factor 2: Prioritization

The initial prioritisation of issues is not easy for system leaders and politicians who often have to deal with many priorities. Genuine prioritisation means accepting trade-offs, focusing on success in one area and, by implication, de-prioritising other potentially important areas.

Critical Success

Factor 3: Data and routines

Critical Success

Factor 4: Understanding and analysis

Regular and reliable performance data are used to monitor progress against milestones and targets. Data informs action plans which are then adapted, targeting support where needed. Feedback mechanisms are in place to ensure that local level actors are using data effectively.

Priorities and targets are understood across the delivery system from the national through to local levels. Systems actors are clear of the role they must play to achieve targets. Plans and targets are based on a solid understanding of issues and what is required to achieve change.

Critical Success

Factor 5:

Accountability

Accountability structures personally chaired by the system leader meet regularly to examine performance data and progress against plans. These structures have a mandate to discuss issues and take action to resolve blockages and constraints to achieve results.

Literature on the delivery approach has often equated the adoption of the approach with the establishment of Centre of Government Delivery Units (at either Presidential, Prime Ministerial or Ministerial level). Recent reports have charted the rise and fall of Delivery Units worldwide but it is important not to see the establishment of a Delivery Unit as synonymous with the application of the delivery approach. Countries can still apply the principles of the delivery approach without necessarily establishing a Delivery Unit and there may be instances where it is advantageous to not establish a separate Unit. They can also establish a Delivery Unit without necessarily following the principles of the delivery approach 3, 4. It may therefore be inaccurate to point to the abolition of a Delivery Unit as evidence that the delivery approach has ‘failed’ in a particular country context.

Do I need to establish a Delivery Unit in order to apply the delivery approach? A series of questions for governments

Does the Government have a clear set of delivery priorities?

Is the Centre of Government using data to regularly analyse performance and take action to improve results?

Do officials at the centre of Government understand what is required to deliver positive results in schools? Do they have sufficient understanding of what motivates teachers?

If YES then a Delivery Unit may not be necessary.

If YES then a Delivery Unit may not be necessary.

If YES then a Delivery Unit may not be necessary.

Does the centre of Government have an existing and effective mechanism for monitoring and performance managing results?

If YES then a Delivery Unit may not be necessary.

Even if you answer No to the questions above a Delivery Unit may not be the most suitable approach depending on the country context. While Delivery Units can be useful in kick-starting an underperforming system and ensuring the effective application of the delivery approach they can also have several drawbacks including:

• Cost: new structures cost money and it is often easier to create new things rather than fix problems in existing systems.

• Recruitment Issues: getting recruitment right is important and not easy. Sometimes too many senior staff are employed or staff are employed who are ‘stuck’ in the existing ways of thinking. Recruiting outsiders is not always the answer either as they may not understand how government functions or they may be resented by the civil service, particularly if they are on higher salaries.

• Establishment of Parallel Structures: actually weakening delivery systems by establishing separate data collection or analysis systems which remove responsibility from mainstream system actors or by seen to be ‘responsible for delivery’ rather than system strengthening.

• Conflict with the Delivery System: Actors in the delivery system refuse to cooperate with the Delivery Unit and seeking to sabotage it by refusing to share information or sharing deliberately inaccurate data.

The delivery approach was initially applied in education systems which had a relatively high level of capacity. There were specific delivery issues which required addressing in the UK, Malaysia etc. but in these systems there were i.) skilled people; ii.) data systems which could be used to monitor and track progress and iii.) the existence of functional delivery systems with relatively well defined roles and responsibilities from national through to school level.

In some of the country contexts in which the delivery approach has been applied these basic enablers do not exist (Sierra Leone for example where, in 2015, District Education Offices had only a handful of staff and no meaningful way of monitoring the hundreds of schools under their jurisidiction).

In these instances the answers to the four questions on the previous slide about establishing a Delivery Unit would suggest that a Unit is the answer. But care should be taken in coming to this conclusion. A Delivery Unit in a low capacity system may end up substituting for the system, particularly if dedicated structures are created through to local level to deal with capacity constraints (this occurred in Sierra Leone with the creation of District Delivery Teams who reported to the President’s Delivery Team).

Such an approach may have merit in enabling the effective project management and delivery of basic results in priority areas but, if the focus is predominantly on delivering the ‘outputs’ in the diagram above and not considering how to establish and sustain the ‘enablers’ in the existing delivery system then there is a danger that, once the dedicated support around the delivery approach is withdrawn, then the system may actually be weaker than before the intervention started.

This suggests that careful thought is needed when considering how to apply the Delivery Approach in systems where these ‘enablers’ do not exist. It is important to consider how the delivery approach can achieve short-term results whilst also strengthening the existing system by developing these enablers.

Whilst the main motivation for the application of the delivery approach in many instances is to achieve short-term results and ‘get things done’ there is an implicit assumption that, by achieving such results, delivery systems will also be strengthened. The system strengthening diagram introduced on the previous slide illustrates the main components required to achieve improved educational outcomes. It consists of a set of 4 outputs required to improve learning outcomes and these outputs are supported by the existence of 5 enablers. In the diagram below we have just presented the ‘outputs’ section of this diagram to illustrate how the four outputs of the system strengthening model are very closely aligned with the four delivery approach principles.

At an output level the delivery approach provides all that is needed within this model to achieve improved learning outcomes- it provides support and capability to analyse and unblock problems; introduces effective management routines linked to timebound implementation plans with clear metrics and ensures that these plans are focused on an agreed set of genuine priorities. If we just look at outputs of the system strengthening model then the delivery approach appears to be a very relevant set of tools and techniques to enable countries to improve educational outcomes. However we must remember that achievement of the four system strengthening outputs is reliant on the existence of five enablers- good data, strong relationships and a culture of collaboration, skilled people, clear roles and responsibilities and clear accountabilities. The relationship between the delivery approach and these five enablers will be discussed on the next slide.

Achievement of the outputs in the system strengthening model is reliant on the existence of five enablers . As the diagram below illustrates there is a certain degree of overlap and correlation between these enablers and 3 of the 4 delivery approach principles. This illustrates that effective application of the delivery approach is reliant on existing conditions within the delivery system. If, for example, good data does not exist then this will need to be produced. In systems where these enablers are not already in place there is a temptation, in order to achieve short-term results, to establish parallel or temporary data collection, roles & responsibilities and accountability systems. These may help to achieve short-term results but will not strengthen systems. Ultimately therefore the delivery approach by itself is insufficient to bring about sustained system strengthening although it can play a contributory role.

It is also noteworthy that one of the key enablers - skilled people - has not generally been a key priority when applying the delivery approach. Yes there has generally been a focus on building skills and capacity at a national level amongst a small core team of staff in the Delivery Unit or similar structure but this has rarely extended down to district or school level. Instead the focus has been on achieving quick results, measuring progress and holding people to account for their performance. Likewise, in some applications of the delivery approach, there has been a much stronger focus on accountability and responsibilities than there has on collaboration and relationship building. Collaboration and cross-departmental working has played an important role in the UK’s PMDU, Malaysia’s PEMANDU and Sierra Leone’s PRP although there is less evidence of this from some of the other case studies in this report.

The 5 ‘enablers’ from the system strengthening diagram discussed in the previous slides appear to be a necessary pre-condition for sustainable system change.

In our country case studies we will examine the extent to which the delivery approach succeeded in bringing about sustained improvements in data collection, analysis and use; established clear roles and responsibilities for delivery; and strengthened and clarified accountability for achieving results. All three of these ‘enablers’ are aligned with the principles of the delivery approach(as the diagram above illustrates) and should be an explicit part of the package of activities and support introduced alongside the approach.

We will also examine the extent to which:

i.) strong relationships and a culture of collaboration (which has been a key principle in the application of some variants of the delivery approach e.g. PMDU 2007-2010 with its focus on cross-departmental Public Service Agreement (PSA) boards) and

ii.) skilled people existed as a possible pre-condition for success (or failure) within each country’s education delivery system.

The delivery approach relies on the premise that a small team of people working in the centre of the education delivery system can introduce prioritized performance management routines backed up by good data which will in turn improve learning outcomes for potentially millions of children. In order for this premise to hold there must be i.) a sufficiently strong and collaborative system to enable instructions and incentives from the centre to reach sub-national and school levels and ii.) a sufficiently skilled workforce to respond effectively to these instructions and incentives so that outcomes and results improve. As mentioned previously, if such enablers are not in place there is a temptation to establish ‘quick fix’ parallel data and accountability systems or roles and responsibilities in order to achieve improvements against a set of activities and outputs. Such an approach is not likely to contribute to genuine system strengthening over the longer-term.

This diagram displays a number of countries which are currently attempting to apply the delivery approach to improve service delivery with a specific focus on education.4

UK, Implementation Unit, 2012

Albania, Delivery Unit, 2013

Romania, Delivery Unit, 2014

Serbia, Delivery Unit, 2015

Jordan, Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit, 2015

Oman, Tanfeedh Delivery Unit, 2016

Saudi Arabia, Central Delivery Unit, 2016

Costa Rica, Delivery Unit, 2015

Guatemala, Delivery Unit, 2016

Peru, Delivery Unit, 2016

Canada, Results & Delivery Unit, 2016

Maryland (USA), Governor’s Office of Performance Improvement

St Lucia, Delivery Labs, 2018

Western Cape, SA, Delivery Support Unit, 2014

South Africa, Operation Phakisa, 2014

Uganda, PMDU, 2016

Ethiopia, Education Delivery Unit, 2017

Guinea, PMDU, 2017

Egypt, Ministry of Education, 2017

Ghana, Education Reform Secretariat, 2018

Punjab, Pakistan, Special Monitoring Unit, 2014

Haryana, India, Department of School Education, 2014

PENGGERAK, Brunei, 2014

New South Wales, Australia, Premier’s Implementation Unit, 2016

A number of Delivery Units and related structures have closed in the past decade, often due to changes in political administration. In some countries similar Units have then been established again by new administrations.

UK, PMDU, 2001-2010

Netherlands, 2006-2010

Wales, 2011-2016

Middle East

Jordan, Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit, 20102013

Indonesia, UKP4, 2009-2015

Malaysia, PEMANDU 2009-2018

Mongolia, 2013-2015

Queensland, Australia, 2004-2007

Australia (Federal) 2003-2015

Chile, 2010-2014

Colombia, Delivery Unit, 2014-2018

Tanzania, President’s Delivery Bureau, 2013-2017

Sierra Leone, President’s Delivery Team, 2015-2017

The widespread establishment of Delivery Units by Governments can be traced back to the formation of the UK Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit (PMDU) by Tony Blair in 2001 under the leadership of Sir Michael Barber. The PMDU was tasked with ensuring that the Prime Minister’s domestic policy priorities were implemented effectively so that they achieved tangible performance improvements and significant results on the ground. The PMDU focused on a relatively small number of key outcomes which were a real priority for the Prime Minister and his Government. Located right at the centre of Government (initially in the Cabinet Office and then the Treasury) with direct access to the Prime Minister the PMDU was kept relatively small, with fewer than 50 staff, and attracted a blend of top talent from the civil service, private sector and frontline service delivery positions in local government.

PMDU was considered to be a successful innovation (particularly after the publication of Sir Michael Barber’s ‘Instruction to Deliver’ in 2008) and it attracted considerable attention from governments worldwide who came to the UK to learn how it operated and see how a similar approach could be applied in their own contexts.5

It should be noted that the PMDU’s remit and mode of operation, whilst remaining fundamentally the same, did alter and flex over the course of its lifespan (2001-2010). This evolution is important as it has influenced the subsequent application and evolution of the Delivery Approach globally over the past two decades. Some of this evolution is helpfully set out in the Institute for Government’s ‘Public Service Agreements (PSAs) and the Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit’ report.6

Head: Sir Michael Barber

Core Functions & Characteristics

- Regular contact with Prime Minister

- Focus on small number of key priorities in education, health, transport & home affairs.

- Strong emphasis on centralised quantitative target setting and performance management against trajectories through routines and publication of departmental ‘league tables’ against 17 priority PSAs.

- Conducting frontline deep-dive ‘priority reviews’ to understand delivery issues.

Head: Sir Ian Watmore

Core Functions & Characteristics

- Less direct contact with PM due to domestic political issues.

- Broader focus and introduction of Capability Reviews intended to assess Departmental performance and build delivery capacity across all Government Departments.

Head: Ray Shostak

Core Functions & Characteristics

- Relocation from Cabinet Office to Treasury.

- Overseeing 30 PSAs which emphasised cross-government working and collaboration.

- Unblocking delivery obstacles through deepdive ‘priority reviews’, problem solving and follow-up brokerage work with departments (consumed most of PMDU’s time).

- Broadening of scope and shift of emphasis onto collaborative problem solving and away from centralised target setting.

PMDU 2001-2005 (Blair) PMDU 2005-2007 (Blair) PMDU 2007-2010 (Brown) CBEThe PMDU’s 2001 to 2005 structure and mode of operations became the template which many governments looked to follow when developing their Delivery Units. This process was accelerated by Sir Michael Barber’s prominent role in promoting Delivery Units, initially with McKinsey and then through Delivery Associates. As governments looked to adapt the original PMDU principles (which Barber termed ‘Deliverology’) variants of the approach inevitably emerged. One distinctive Delivery Unit (DU) variant was developed in Malaysia as the Performance Management and Delivery Unit (PEMANDU) in 2009. PEMANDU’s approach (initially supported by technical advice from McKinsey) was based heavily on private sector operating practices introduced by PEMANDU’s CEO, Idris Jala who was a former head of Malaysia Airlines. Idris Jala introduced a methodology called Big Fast Results - 8 Steps of Transformation. A key feature of this approach was the operation of large-scale ‘Delivery Labs’ which lasted for several weeks enabling prominent stakeholders to develop detailed implementation plans (3 Feet Plans) to achieve Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). PEMANDU’s Delivery Labs and the resulting Plans were publicized through media engagement and Open Days. PEMANDU itself was a large organization, employing over 130 people from both the public and private sectors and it operated like a private sector company, publishing an Annual Report setting out progress against the Government Transformation Programme (GTP) and Economic Transformation Programme (ETP). PEMANDU ceased operating as a government entity in 2018 and became a private consulting firm ‘PEMANDU Associates’ which now works with countries such as St Lucia and Nigeria.

PEMANDU has played an important role in publicizing their particular Delivery Unit approach internationally, most notably through the experience of Tanzania where President Kikwete adopted the PEMANDU model wholesale in 2013, terming it ‘Big

Now!’. The Tanzanian model was headed by the President’s Delivery Bureau (PDB) and the former head of the PDB, Omari Issa, has in turn played an important role in promoting the ‘delivery labs’ model through the Education Commission, influencing practice in countries such as Ethiopia and Uganda.

Another highly influential application of the Delivery Approach was that adopted in Punjab, Pakistan spearheaded by Sir Michael Barber (initially as part of McKinsey and subsequently on an independent basis). The Punjab Education Roadmap drew heavily on Deliverology and focused intensively on monitoring a small number of priorities using the considerable authority of the Chief Minister to ensure progress, delivering impressive results.

Elsewhere Management Consultancy companies such as Dalberg (in Guinea) and McKinsey (in Sierra Leone, drawing upon their experience in Punjab) have promoted variants of the approach along management consultancy lines. Some countries have also been influenced by the more nuanced approach taken by the UK’s PMDU between 2007 and 2010 in focusing on collaborative system strengthening rather than target setting. In Ministries of Education in e.g. Uganda and Haryana, India these ideas have coalesced with concepts such as Problem Driven Iterative Adaption (PDIA) capacity building and problem-solving to strengthen systems from local to national, focusing on the application of principles rather than establishment of structures.

Over time these various influences and experiences have coalesced as new countries have drawn upon technical advice from various experts and organisations. For example the Ethiopian Delivery Unit was established with technical advice from Delivery Associates (drawing on Deliverology and the UK PMDU 2001-2005 experience) but the Ethiopian Government was also insistent that this approach should incorporate Labs ( drawing upon Tanzania’s experience in 2013 which was in turn influenced and facilitated by PEMANDU). It is therefore becoming increasingly difficult to trace a single line of influence from one application of the delivery approach to another.

As previously explained many of the examples set out below have been influenced by a combination of the ‘origin’ models (with the UK PMDU 2001-2005 experience being particularly influential) so the table below simply serves to illustrate some of the main connections between different country approaches. Some countries e.g. Nigeria, Ghana and Uganda have already experienced different applications of various models by sector, donor and administration.

UK PMDU 2001-2005 & Delivery Associates (Deliverology)

PEMANDU, Malaysia

2009- 2017

PEMANDU Associates 2018 to present

Management Consultancy Variants

McKinsey, Deloitte, Dalberg, AGI

UK PMDU 2007-2010

Global evolution (BCG) and incorporation of PDIA

• Personal engagement of senior system leader.

• Small number of key priorities.

• Focus on centralised target setting & regular performance monitoring routines.

• Focus on local problem solving.

• Limited external publicity.

• Tools and techniques codified as ‘Deliverology’.

• Large structure with over 100 staff.

• Led by private sector CEO.

• ‘Delivery Labs’ large, intensive prolonged problemsolving sessions with key stakeholders

• Strong focus on publicity and communications including the publication of Annual reports and holding of Open Days

• Influenced by McKinsey’s involvement in Punjab and PEMANDU establishment.

• Packaged the steps of ‘delivery’ in an accessible management consultancy format.

• Relies on pace of implementation and rigour of analysis.

• Dependent on international technical assistance, often shortterm.

• Initial focus on performance framework e.g. PSAs.

• Focus on deep dive problem solving reviews.

• Consideration of principles ahead of structures- use of existing systems.

• Local experimentation

• Managing for results and building capacity within delivery systems from districts and schools upwards.

• Punjab Roadmap (Education)

• Western Cape (SA)

• Egypt (Education)

• Ethiopia

• New South Wales (Australia)

• BRN! in Tanzania

• South Africa (Operation Phakisa)

• Oman

• Andhra Pradesh (India)

• St Lucia

• Sierra Leone

• Rwanda

• Nigeria

• Guinea

• Uganda (Ministry of Education)

• Ghana (Education Reform Secretariat)

• Haryana (India)

• Colombia

The diagram below sets out the various stages of the delivery approach with examples of approximate costings and timings depending on the model used.

Step 1

Initial Preparation and Prioritisation

Preparation is the most critical phase of all as many issues need to be thought through in detail prior to implementation of Step 2.

Countries must carefully consider their current situation and whether they need to establish new structures to implement the delivery approach. There must be extensive stakeholder engagement and assessment of institutional readiness.

Prioritisation may be relatively simple if the Minister or senior officials have clear priorities from a manifesto or within an Education Sector Plan. At the other end of the cost spectrum the Delivery Lab (set out separately here as Step 2) can be used for prioritisation.

The main cost driver is the extent to which external consultants are required to conduct preparatory analysis.

Step 2

Diagnostic Fieldwork or Delivery Labs

Once priorities have been identified diagnostic fieldwork is required to understand the issues and engage front-line workers in problem solving. This can be done at a relatively low-cost through targeted stakeholder engagement and fieldwork or at much greater cost if a large-scale, public Delivery Lab is held.

A 4 week Deep Dive exercise in Ghana involving stakeholder workshops and Ministry staff conducting fieldwork to selected Districts and schools cost $50,000 including all staff inputs.

The cost of holding a 6 week Delivery Lab using the PEMANDU model was estimated by DFID to be $350,000 in Tanzania excluding staff and consultant’s time. The total cost of a 6 week Delivery Lab estimated in the Education Commission’s pioneer country work was $2,000,000.

Step 3

Establishment of structures and communications

The establishment of structures can be done concurrently with the preparation and prioritisation phase so that people are recruited and trained . Delays in establishing structures and finalising staffing can result in a critical loss of momentum following Step 2.

The cost of this step can vary considerably depending upon i.) the size of the structure, ii.) the staffing of the structure (private sector and external recruits will cost more than civil servants already on the payroll) iii.) the extent to which the structure is dependent upon international expertise and iv.) the extent and reach of the communications activities publicising the structure and Delivery Approach plans.

The cost of establishment can increase significantly if Units are created at regional and/or district level. From experience such Units may undermine the delivery system and create parallel structures.

Step 4

Operation of data and performance routines

Data gathering and performance management routines are critical to effective functioning of the delivery approach. Costs can vary considerably from being minimal if a decision is made to use existing information gathering systems e.g. district-level circuit supervisors or ward education coordinators to being quite expensive if new methods of data collection are introduced (either using tablets or other electronic means or by recruiting dedicated external monitors to gather school level data).

Performance management routines involve holding regular meetings chaired by the senior system leader and then providing feedback to relevant actors throughout the system. If there is commitment from system leaders and others then this does not need to be an expensive element of the delivery approach.

Step 5

Implementation of priority initiatives

If initiatives are already funded through existing government budgets then this stage will have no cost (other than the ongoing operational costs of structures and data routines listed in Steps 3 & 4).

If dedicated funding is required to implement the Delivery Plans developed during Steps 1 and 2 then the cost could be very significant indeed. Payment By Results funding support and incentivisation programmes such as those operated by DFID, World Bank and SIDA can also run into the $100s of millions.

Should implementation of the delivery approach be time-bound?

There are advantages to seeing it as a short-term (3 to 5 year) catalyst to system reform although improving learning outcomes can take much longer. Even the most notable Units have had a finite lifespan e.g. (UK PMDU 20012010), PEMANDU 2009-2018).

TIMING: 3 to 6 months

COST: minimal to $millions

TIMING: 4 to 8 weeks

COST: $50,000- $2,000,000

TIMING: 1 to 4 months

COST: $200,000-$5,000,000 annually

TIMING: 2 to 6 months

COST: minimal- $5,000,000 annually

TIMING: ongoing for 3 to 5 years

COST: $0 - $100s of millions

Whilst some applications of the delivery approach can be ‘linear’ with little considered analysis or problem solving after plans are developed (as with the initial application of the PEMANDU’s ‘3 Feet Plan’ approach in Tanzania) to truly apply the principles of the delivery approach it is important to take an iterative perspective and be prepared to adapt plans and approaches based on ongoing analysis and problem solving from within the system. Ideally what is required is a ‘strong’ centre of government which clearly articulates priorities and targets across the system which local level actors (within Districts or schools)then have sufficient autonomy to think creatively about how best to achieve within their own context. This may well require capacity building, training and support below sub-national level- something which has not been considered in some applications of the delivery approach.

Step

Initial Preparation and Prioritisation

Step

Step

Operation of data and performance routines

Step

Implementation of priority initiatives

Regular reviews – to connect system levels and enable decision makers to unblock larger problems

Initial diagnostics, priorities and plans

Real-time management results and analysis

Leading to

Problem analysis, solutions and adaption of plans

When PMDU was established in the UK in 2001 it was designed to be relatively low cost and add value by unblocking delivery obstacles within existing government programmes. It had an operating budget which included the salaries of approximately 40 staff (a mixture of civil servants and secondees from management consultancies and local government) and a limited budget for administration and fieldwork.

Subsequent variants of the delivery approach have varied significantly in cost with the PEMANDU model (requiring over 100 staff and the conduct of Delivery Labs which can cost over £1 million per time) being the most expensive. Much of the cost of establishing the delivery approach in many countries has come from the management and technical assistance fees charged by international ‘experts’ and consulting companies. DFID committed £39 million to the establishment and operation of the Tanzanian Big Results Now! Programme with the bulk of this going to PEMANDU’s fees, staffing costs of the large Presidential Delivery Bureau (PDB) and Ministerial Delivery Unit (MDU) structures and conduct of Delivery Labs.

One of the key principles in the UK PMDU was that money would be ‘off the table’ when it came to finding implementation solutions i.e. that the system would need to find ways of achieving results with the same amount of money. This was based on the belief it is always possible for systems to improve and that, if money was ‘on the table’ it would remove the impetus to improve the system as more funds would simply substitute for systems shortfalls and inefficiencies. Departments and Agencies at all levels of the delivery system therefore worked within the constraint that if they wanted more resources for a specific initiative then they had to reallocate it from elsewhere in their operational budget. All delivery plans were therefore fully costed and funded from Department’s own budgets.

In a developing country context funding constraints are often more acute. This has meant that plans and priorities drawn up through Delivery Labs and other prioritisation exercises in countries such as Tanzania and Sierra Leone have had significant funding shortfalls. Rather than working within the existing resource envelope the application of the delivery approach in these contexts has become more ‘projectized’ as development partners have had to step in with dedicated funds to fill these funding gaps. This has a significant disadvantage in that the delivery system then views the delivery approach as a discrete donor project (often perceived as driven and led by donors not government) rather than as a mechanism for system strengthening and increasing accountability. Two ways to potentially overcome this issue are:

i.) to make use of existing donor funded programmes and coordinate and direct them to help achieve results required under the delivery approach.

ii.) to establish a Payment By Results (PBR) mechanism with agreed Disbursement Linked Indicators (DLIs) with funds then dispersed to government once they have themselves achieved agreed milestones towards the expected results required under the delivery approach. This approach can be effective particularly if the PBR arrangements encompass local government units which receive resources when they achieve results.

We looked in detail at 5 country case studies, conducting interviews and analyzing data to assess the impact of the delivery approach and the extent to which the Critical Success Factors from Slide 8 were followed.

Tanzania

Assessing the effectiveness of the Big Results Now! (BRN) education initiative and subsequent Programme for Results (P4R) from 2013 to 2019.

Sierra Leone

Assessing the effectiveness of the President’s Recovery Priorities (PRP) in Education from 2015 to 2017.

Punjab, Pakistan

Assessing the effectiveness of the Punjab Education Roadmap from 2011 to 2019.

Haryana, India

Assessing the effectiveness of the Quality Improvement Programme and Saksham Haryana from 2014 to 2019.

Ethiopia

Assessing the effectiveness of the Education Delivery Unit from 2017 to 2019.

We also provided briefer descriptions of some other notable applications of the delivery approach: the UK’s Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit (PMDU) – the original model which many governments sought to emulate; Malaysia’s PEMANDU- an influential and distinct approach; Colombia’s Presidential Delivery Unit- an example of the application of the delivery approach from South America; Indonesia’s UKP4 – an example of a Presidential-level Unit which became overloaded with multiple priorities; and Ghana’s Education Reform Secretariat- a very recent example of a nuanced application of the Delivery Approach.

Section 3 summarises the main findings from this multi-country analysis.

Section 4 provides more detailed findings from each of the country case studies.

This illustrative graph shows that the quality of enablers (from Slide 13) can be a barrier or catalyst to the effectiveness of the delivery approach in bringing meaningful system change. The relationship between enablers and the systemic impact of delivery approaches

• Some of the most high profile examples of delivery come from systems where the enablers were already strong. This allowed the delivery approach to act like a laser beam to resolve key issues in focal areas, building on a sound foundation.

The impact of delivery approaches in systems with high quality enablers has generally been focused on specific areas of the education system (‘laser beams’ to resolve particular problems) rather than bringing about holistic system change as many parts of the system are already functioning effectively.

Quality of enablers

• In systems where these enablers are not in place, delivery approaches have been less successful in delivering meaningful system change as they have to build short-term fixes to boost the enablers or bypass them entirely with parallel systems.

• While the delivery approaches that have been built in systems with weak enablers have still had areas of short term impact in achieving results (e.g. Sierra Leone), they have been less successful at developing lasting systemic change.

The four by four matrix below classifies educational outputs and outcomes by a combination of their technical complexity and political difficulty.7 From the evidence considered in the country case studies we believe that the delivery approach can be most effective in achieving results in the two left hand quadrants of this model where the linkages between activities and outputs are clearly understood by actors within the delivery system i.e. those which have ‘low’ technical complexity and lend themselves to a target-based performance monitoring regime.

Addressing these ‘left-hand’ issues is important as, if left unresolved, such issues often form a barrier to the achievement of the more technically complex issues in the right hand quadrants. The delivery approach can be particularly useful in tackling issues in the top left-hand quadrant where support and commitment from a system leader can resolve problems which have been traditionally hard to unlock.

The case studies and the literature in this field suggest that success is much harder to achieve in areas where the logical link between activities, outputs and outcomes is less clear (and harder to measure- there is a danger with the delivery approach that the focus shifts to the easily measurable rather than the genuinely important). As an example, international evidence suggests that teachers are often not clear as to the logical linkage between specific behaviours and improved learning outcomes.20 Putting great stress on achieving outcomes can thus lead to demotivation if the person or institution being incentivised or held to account doesn’t feel it is within their power to improve. An example of this would be a head teacher who is held to account for poor exam results when he or she doesn’t have the authority to hire, effectively discipline or dismiss their teaching staff. In such a situation effective incentives would be those which are linked to specific behaviours which teachers, head teachers and officials have the capability to achieve.

The case studies show that the delivery approach can have considerable success in areas such as improving pupil and teacher attendance and increasing capitation grant flows but that it appears to have been less effective in addressing complex system issues such as reforming teacher performance and career development and improving learning outcomes where i.) strong enablers are required to achieve success and ii.) where the technical linkage between activities and outputs is more context specific and less clear.

Outputs and Outcomes classified by Technical Complexity and Political Difficulty

Teacher pay & conditions

Hard

Political Difficulty

Teacher absenteeism

Improved vocational training system

Initial Teacher Training (ITT)

Easy

In-service

Teacher Training (INSET) Regular release of

school capitation grants

Pupil attendance

Teacher performance & career development

Improved learning outcomes

Simple Complex

Technical Complexity

Evidence from the country case studies suggests that the delivery approach may be effective in addressing technically simple issues which can be easily measured where there is a clear link between activities & outputs/outcomes.

Despite some stories of improvements and increases there is limited evidence from the country case studies that the delivery approach has led to a widespread, genuine and sustained improvement in learning outcomes.

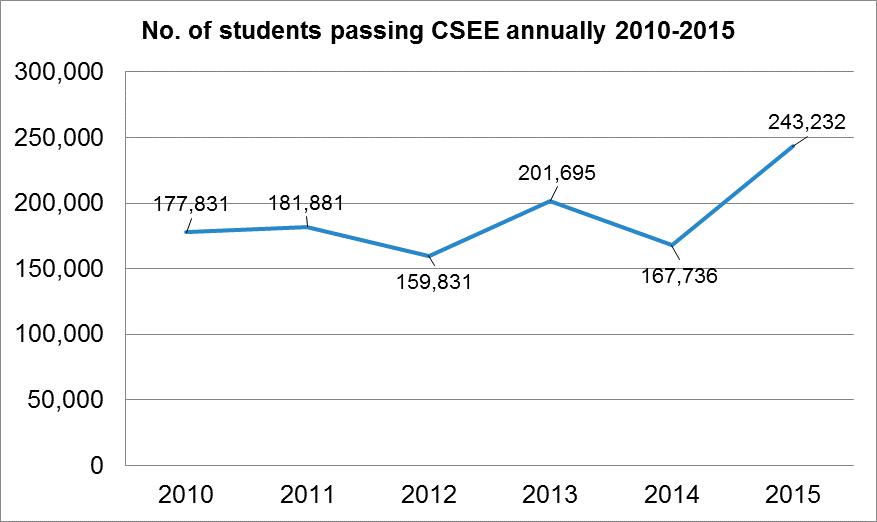

• In Tanzania there was a significant improvement in primary and secondary examination pass rates between 2012 and 2015 (the period in which BRN! was operational). However there were a number of factors – including i.) the change in examination methods which made it difficult to legitimately compare results year on year and ii.) the reduction in the number of pupils sitting examinations- which complicate the initial picture of significant improvement. RTI’s national Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA) results do show that there was a significant and verifiable reduction in the proportion of ‘non-readers’ in Kiswahili in Grade 3 from 27.7% in 2013 to 16.1% in 2016.8 These improvements were not sustained however and the latest EGRA information suggests that 2018 rates have reduced to levels comparable with 2013 probably due to the significant increase in primary enrolment & class size occasioned by the introduction of fee free education in early 2016.

• In Sierra Leone the President’s Recovery Plan (PRP) did not have a specific target for improving learning outcomes or increasing examination pass rates although this was the general aspiration of the plan. Instead the PRP was focused on putting in place the basic ‘building blocks’ of the education system (producing standard lesson plans, verifying the teacher payroll, constructing classrooms etc.). There were some improvements in examination pass rates in 2016 and 2017 but these rates fell in 2018.

• In Punjab learning outcomes were not an initial focus for the Education Roadmap but they then became a focus from 2014 onwards. Six monthly learning assessment carried out by the Roadmap team suggest significant improvements in Grade 3 literacy and numeracy from 2016 onwards. These findings have been widely questioned however, including by former members of the Roadmap team, who noted that the reductive focus on 15 learning outcomes which were tested monthly meant that teachers taught to these tests and not the curriculum. 9,10,11

• In Haryana there have been improvements in literacy and numeracy since the introduction of the Quality Improvement Programme in 2014. India’s annual ASER report compares literacy and numeracy in Standard V government schools across all States. The latest (2018) ASER report shows that Haryana has seen improvements in literacy and numeracy between 2014 and 2018 but that these improvements have not been exceptional. On Standard V reading Haryana was ranked 4th out of 18 states in 2014 and had fallen to 5th in 2018 and ranked 11th in terms of percentile improvement during this period (20142018) out of the 18 states. On Standard V division Haryana was ranked 5th in 2014 and 3rd in 2018, and ranked 12th in terms of percentile improvement (2014-2018). ASER data therefore suggests that Haryana has not outperformed other States which did not adopt the delivery approach.12

• In Ethiopia it is too early to measure the impact of the delivery approach on learning outcomes.

Looking beyond these developing country case studies there is evidence from the UK that the delivery approach methods used in the London Challenge did lead to a genuine and sustained improvement in results in London primary and secondary schools. In 2003 these schools were below the national average but by 2010 they were ahead of the national average and this situation still persists. It is important to note that this is a sub-national change and that efforts to replicate the methodology in other areas of England were not as successful. In Malaysia PEMANDU and the Ministry of Education claim that Literacy and Numeracy Screening (LINUS) led to significant improvements in learning outcomes since 2009. A 2018 World Bank report however notes that there is insufficient evidence to state whether LINUS has actually improved reading and numeracy skills of early graders due to the lack of key data. 13

Delivery approaches can bring about rapid change by focusing on performance improvements of measurable issues. While this can be a force for good, applying pressure to achieve rapid, measurable change can also bring about some negative unintended consequences where the cause-effect relationship between activities and targets is more complex.

BRN!, Tanzania – Pupils being excluded from examinations

• Recent research funded by the Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) Programme came to two contrasting conclusions about BRN! and learning as it relates to the School Ranking initiative (where primary schools were publicly ranked according to PSLE pass rate):

• BRN School Ranking improved learning outcomes for schools in the bottom two deciles of their districts.

• The School Ranking also led some of the poorest performing schools to strategically exclude students from the terminal year of primary school.

Punjab, Pakistan – Increases in exam manipulation and a narrowing of teaching to focus on what was being measured rather than what was in the curriculum

• Interviews indicated that when the performance management target focus was on exam results in 2013/14 this increased cheating and fake results.

• When the focus switched to monthly competency-based assessments, where only 15 or so numeracy and literacy competencies were measured, teachers learnt to game the system but teaching to those test and ignoring the majority of the curriculum. Pupil performance increased based on the test data, but it is more debatable whether learning had systemically and sustainably improved.

Punjab Education Roadmap

• Significant increase in student enrolment.

• Reduction in teacher absenteeism.

• Increased supply of textbooks and educational materials.

• Increase in the number of schools with basic facilities.

Haryana, Quality Improvement Programme/Saksham Haryana

• Increase in number of teachers undergoing structured in-service training.

• Improvement in distribution of teaching and learning materials.

• More regular school inspections and improvements in operation and scope of MIS.

Tanzania, BRN! & EP4R

• Increase in regularity and timeliness of capitation grants reaching schools.

• Increase in the number of schools holding remedial classes and extra lessons.

• Improvements in teacher deployment and allocation.

• Improvement in availability of publicly available examination data.

Sierra Leone, President’s Recovery Priorities

• Distribution of structured lesson plans to all primary and junior high schools.

• Construction of classrooms and WASH facilities.

• Reduction in number of unapproved schools.

• Expansion of school feeding programme.

These examples illustrate that, regardless of other claims made about it, the delivery approach can achieve timely and tangible results in easily measured (and sometimes previously neglected) areas.

from the country case studies shows that the delivery approach did have a significant impact in achieving results across a variety of areas related to educational inputs and outputs.

There is some evidence from the country case studies that the delivery approach has led to a greater focus on achieving results.

Punjab Education

Roadmap

• The Punjab Education Roadmap’s regular performance ‘heatmaps’ and stocktake meetings with the Chief Minister had a significant impact on officials throughout the delivery system. At the start of the Roadmap process the Chief Minister would summarily fire prominent officials on the spot from those districts which were performing poorly on the heatmaps.

• This led to a culture of fear throughout the districts and a relentless focus on achieving the specific performance metrics linked to the Roadmap. Whilst this led to increased accountability it also enhanced incentives for ‘gaming’ targets.

Haryana, Quality Improvement

Programme/Saksham

Haryana

Tanzania, BRN! & EP4R

• QIP and Saksham Haryana have undoubtedly ensured that there is a far stronger focus on learning outcomes than had previously been the case in the State. There is also a much greater emphasis on monitoring individual pupils’ learning levels on a regular basis and using this data to measure progress.

• It is not clear however that this increased focus has led to fundamental changes in teacher accountability.

• BRN! did not fundamentally change accountability mechanisms, performance appraisal or promotions across the education delivery system but it did have an impact through a ‘top-down’ bureaucratic focus on results and targets. These encouraged officials throughout the system to focus on measures to improve exam results although it had the perverse incentive of leading to some children being excluded from taking exams in poorer performing schools.

• EP4R uses financial incentives to improve performance at a district level but uncertain whether this is sustainable.

Sierra Leone, President’s Recovery

Priorities

• Led to some cultural change within the national Ministry of Education, Science & Technology (MEST) as Directors held weekly meetings with the Deputy Minister every Monday morning to report on progress against their designated activities (with the Minister meeting the President every Thursday). This did lead to staff in the national Ministry taking a greater interest in results but it had very little impact on accountability at sub-national level particularly as many of these activities involved NGOs and other third parties as implementing agencies. Meeting routines ceased once PRP ended.

The examples above show that, whilst the delivery approach can have some impact on encouraging a greater focus on accountability for results, there is a danger that it could lead to the introduction of a parallel accountability system which narrows the metrics used to judge success to such an extent that it encourages gaming and perverse incentives. Setting a pass rate target as a percentage (rather than an absolute number) for example led to some schools in Tanzania excluding the poorest performing pupils

• The cost of the significant number of external monitors (initially retired Army officials) was covered by the World Bank and these monitors were already in place before the Roadmap commenced in 2011. Initially the monitors used a paperbased reporting system but this was upgraded to an electronic system using tablets.

• Despite the change in government in 2018 these monitors remain employed and they are now mostly younger graduates of LUMS. Their cost is still covered externally (World Bank) rather than being absorbed by government.

• There was a focus on regular data collection and assessment including inspection visits to all schools every two months and the introduction of a dashboard based on competency-linked assessment carried out by teachers on their students six times a year. As these assessment are conducted by teachers rather than external assessors then the cost of gathering such data is lower than it would otherwise have been. Haryana has relied on external funding support from the Michael and Susan Dell Foundation to establish these data collection and analysis systems.

• BRN! did not establish a new data collection system but made use of existing data sources and introduced the requirement that districts and regions needed to complete a simple one-page reporting template electronically each month. This was low cost and did not rely on external funding but the quality of reporting was variable.

• EP4R incentivized government to take efforts to improve EMIS and collection and analysis of sub-national data, there is some evidence that this has led to improved data use at local level.

• The PRP made use of the UNICEF RapidPro SMS reporting system to gather data on a monthly basis from all districts and schools. This system was first used as part of the early warning network to combat the spread of the Ebola Virus Disease (EVD). It’s operation relied on a group of external ‘volunteer’ monitors who visited schools and entered data on key metrics which then went straight to the national Ministry and UNICEF. Districts themselves found it difficult to access this data as it was centralized and the cost of the system was borne by DFID. At the end of PRP the approach was discontinued as the Government had relied on external funds to cover the costs of the monitors.

Those variants of the delivery approach which introduced new data collection systems reliant on third parties (the monitors in Punjab and the situation room volunteers in Sierra Leone) came at a cost which was borne externally by donors and not integrated within the government system. The systems in Tanzania and Haryana are administered by existing staff (local officials and teachers) so the cost is lower and there is greater likelihood that they will be sustained beyond the existence of external funding.

Punjab Education Roadmap Haryana, Quality Improvement Programme/ Saksham Haryana Tanzania, BRN! & EP4R Sierra Leone, President’s Recovery Priorities. Globally application of the delivery approach has not tended to survive changes in political administration. In a number of cases this is because the approach or delivery units which personified it were seen as a high profile representation of what the incumbent President or Prime Minister believed in.

• In Tanzania BRN! and the accompanying institutional architecture of the President’s Delivery Bureau and Ministerial Delivery Units were abolished by President Magufuli when he came to power in later 2015 (it took many months for this to be communicated officially but in practice the PDB ceased having influence as soon as the new President came to power). Elements of the delivery approach have continued through EP4R and through a group of officials within the education system who continue to approach issues with a delivery mindset.

• In Sierra Leone the President’s Recovery Priorities (PRP) were always intended to be a short-term initiative which ended in 2017. There was then a change of government in 2018 which led to some major changes in the education system including the division of the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST) into two separate Ministries representing basic and higher education. As of 2019 there is very little evidence remaining of the impact of the PRP, even to the extent that DFID invited Sir Michael Barber to visit Sierra Leone and talk to the new Minister of Education as to how ‘deliverology’ may be used to achieve results within the sector.

• In Punjab the architecture of the Roadmap remains in place despite a change of government in mid-2018. In part this is because the PMIU and data collection mechanisms are both elements of a programme of assistance and technical supported provided by the World Bank which has bridged the two administrations. Elements of the approach are likely to survive the change in administration although they may be adapted and altered in some ways (which are not yet clear) over the coming years.

• In Haryana there was a change in ruling party at State level in October 2014 (with the Quality Improvement Programme being initiated earlier in 2014) but this did not impact the implementation of the programme which was led by the Department of School Education. Next elections are October 2019.

• In Ethiopia the change in Education Minister early in the process was a major setback to the effective application of the delivery approach.

• In Malaysia PEMANDU was abolished when a new government came to power in May 2018. The incoming government had been critical of PEMANDU whilst in opposition describing it as having failed on its main KPI and failing to be accountable to Parliament and the public.

• In the UK the PMDU was abolished in 2010 by a new government which saw it as representing the previous administration’s approach to public service delivery. A similar unit (under a different name, the Implementation Unit) was then re-established in 2012.

Within a functional democracy transitions of power and new approaches to service delivery are an inevitably. Rather than being a permanent fixture delivery units and the delivery approach may be an important catalyst to longer-term system change by harnessing energy to focus on under-served issues and address problems where the solutions are not technically complex. Having a temporary (e.g. 3 to 6 year) timeframe for the application of such processes may be one way of harnessing their benefits without creating long-term parallel systems which do not actually strengthen education systems. We should not view the abolition of a delivery unit as direct evidence of failure.

. Some applications of the delivery approach had a specific focus on promoting private education whereas others were more concerned with government schools.

Roadmap

• The Roadmap encouraged the promotion of private education through the Punjab Education Foundation. Significant resources were committed to PEF and it achieved encouraging results. The government viewed private education as an important means of increasing enrolment and attainment within Punjab and the Roadmap played a role in making this happen. The new government, elected in mid-2018, cut PEF’s funding as they saw the approach as being closely aligned with the previous Chief Minister.

• Private education plays an important role in Haryana but it was not an explicit focus of the initial Quality Improvement Programme. Much of the ASER data used to measure success only uses results from government schools.

Haryana

• There has been a slight reduction in the proportion of pupils enrolled in private primary schools over the course of the programme but this figure still stands at 55% as of 2018.

• BRN! did not have an explicit focus on private schooling. Private education has not historically been encouraged in Tanzania due to the prevailing ideology on public goods first initiated by President Nyerere at independence. Private schools were included within the BRN! targets and, after some discussion, it was agreed that some private schools would be recognised through the school incentive scheme (although excluded from monetary rewards).

• The Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST) was, at the time of PRP, focused almost entirely on supporting the government system rather than considering private education. Private schools (prevalent mostly in urban areas in Sierra Leone) were seen as problematic as many government teachers would also be employed as private school teachers whilst still collecting their salaries. Private schools were therefore not included in PRP activities.

The delivery approach is a set of tools and techniques which can be used to promote private education if the incumbent administration wishes to do so. The example of the Punjab shows that the private sector can respond to the system of targets, incentives and hard and soft levers which are typically deployed through the delivery approach. Countries looking to focus the delivery approach to promote or improve private education should consider which of these tools and techniques are more likely to be effective given the context e.g. top-down bureaucratic pressure is liable to be less effective when deployed with private sector actors as it is when applied to sub-national governments and officials.

Punjab Education Haryana, Quality Improvement Programme/ Saksham Tanzania, BRN! & EP4R Sierra Leone, President’s Recovery Priorities

Improvements in learning outcomes rely on the quality of interaction between teacher and student. The diagram below from Cambridge Education sets out the multi-faceted and inter-related nature of teacher performance and the range of factors which need to be addressed in order to shift systemic capacity to improve learning outcomes. The boxes in red assess the extent to which applications of the delivery approach have addressed each of these factors.

Generally a high priority

This has been the major focus of most applications of the delivery approach- using regular performance data to hold officials to account for results and to clarify responsibility for specific activities through roadmaps and delivery plans. Accountability can be either low stakes (naming and shaming, rankings etc.as in Tanzania and Sierra Leone) or high stakes (leading to dismissal or disciplinary procedures as in Punjab).

Generally a low priority

There have been efforts to promote merit based recruitment and promotion in Punjab but generally applications of the delivery approach have paid less attention to teacher pay, promotion and conditions. In Tanzania efforts were made to reduce salary arrears but there are few examples of systemic changes in this area.

Generally a medium priority

Most applications of the delivery approach have seen a strong focus on in-service teacher training, recognising that there are capability and capacity gaps which must be addressed if learning outcomes are to improve. Such initiatives have not fundamentally changed the structure of teacher training nor addressed initial teacher training (PRESET) where the longer term timeframe to achieve results has seen it generally overlooked in delivery plans.

Generally a low priority

These factors are critically important but less tangible to measure and do not lend themselves to easily quantifiable outputs. As a result they have not really feature in applications of the delivery approach. BRN! did have an activity called ‘teacher motivation’ but this was restricted to measuring payment of salary arrears.

. Whilst it has clearly proved effective in achieving short-term results across important areas of the education system in a number of countries the evidence of the effectiveness of the delivery approach in bringing about sustained improvements in learning outcomes is far from conclusive.

This may be because, in relation to the ‘teacher performance’ diagram on the previous slide, the delivery approach has generally focused on shifting metrics concerning accountability and responsibility, combined with the roll-out of large scale inservice teacher training programmes (and corresponding materials production and distribution). There has generally been less focus on longer-term changes to initial teacher training systems, teacher promotion, recruitment, pay and conditions and other measures to raise the status of the teaching profession and raise morale and motivation. These issues are generally quite complicated and will take a number of years to show tangible results so are often overlooked when countries develop initiatives and metrics where progress must be demonstrated in a matter of months.

The delivery approach can thus play an important role in helping to bring about system reform and strengthening by focusing on a small number of priorities and driving improvements, shining a ‘laser beam’ onto system inadequacies which have remained hidden for decades and addressing issues at school and district level which have constrained national progress. The delivery approach can help to catalyse change but it cannot, by itself, bring about widespread systemic reform as such reform involves multiple areas (not a small number of measurable priority programmes) and longer-term changes.

In countries where the key ‘enablers’ are already in place and system capacity is relatively high the delivery approach has had some success in addressing more complex issues as well as simple measures such as improving delivery of inputs (which are still important in their own right). In such higher capacity contexts the approach has been useful in addressing specific issues and bringing about improvements but this is a very different matter to attempting to use the delivery approach to comprehensively reform a failing system. In summary, for countries with capacity constraints, the delivery approach has merit in enabling governments to focus on priority areas in an Education Sector Plan and achieve against some key priorities which lend themselves to simple and regular metrics. We would not recommend using the delivery approach to try and implement the Education Sector Plan in its entirety- the education system may become exhausted with the data and performance management requirements whilst prioritization will not be possible. A rigorous performance management routine can also be most effective when it is time-limited- meaning that delivery units do not necessarily need to become permanent fixtures.

When looking at the initial set of public service delivery challenges mentioned at the start of this paper one of the challenges mentioned was “focus in government on process and procedures rather than outcomes.” Studying various applications of the Delivery Approach it is clear that processes and procedures are necessary pre-conditions to achieving outcomes. Processes and procedures are important to establish effective performance management routines and ensuring that data is analysed and used regularly to inform decision-making. Without this focus on routines there is a danger that the work of a Delivery Unit is conducted on an ad hoc basis or that it’s analysis does not link in to the systems which it is ultimately trying to improve.

The challenge then for government is not necessarily to remove processes and procedures but to ensure that these processes and procedures are focused on achieving outcomes rather than being seen as an end in their own right.

Whilst the evidence in this report suggests that the Delivery Approach has been more effective in achieving results for technically simple issues where progress can be measured regularly and unambiguously it is worth stressing that this does not necessarily mean that it cannot be used to improve learning outcomes. We would recommend that countries should examine the evidence which exists within their specific context as which technically simple and measurable activities and outputs may contribute towards improved learning outcomes. The Delivery Approach can then be used to oversee a programme of activities which, according to evidence, should lead to improved learning outcomes if implemented effectively. The advantage of this approach is that the targets and incentives used to hold institutions and individuals to account will be clear and measurable. If these measurable results are achieved and the logical linkages between outputs and outcomes holds then learning outcomes should improve.

The evidence presented in this report is inconclusive on the effectiveness of the Delivery Approach in achieving improved learning outcomes. Some of the applications of the Delivery Approach did not have an explicit focus on learning outcomes whilst others were only implemented for too short a period of time to have an impact on learning outcomes. It should be noted that, in cases such as Haryana, there was an improvement in learning outcomes over time, just that the scale of this improvement was not significantly greater than that experienced in other States.

.

• The delivery approach can be implemented effectively without establishing a separate Delivery Unit, embedding the approach within existing structures and systems is preferable if sufficient capacity exists.

• The delivery approach is not a guaranteed solution for system strengthening but it can be an effective way to kick-start performance improvements and deliver measurable change in clearly defined areas of the education system.

• The delivery approach is well suited to technically simple issues where progress can be measured regularly and unambiguously. The delivery approach tends to be less effective on complex, systemic change issues.

• There is some evidence for the delivery approach supporting short-term improvements in learning outcomes but the evidence is not conclusive, improvements may not be sustained and there is a risk of unintended consequences.

• Effective delivery systems require strong enablers not just process. Delivery approaches may not necessarily strengthen these enablers as they are focused on short-term results which often requires parallel systems to initiate rapid change in systems where the enablers are weak.

• Delivery approaches do not survive political transitions well but they may not need to, the first 3-6 years could be where the biggest value comes from rather than seeing them as a permanent presence. They can be used to kick-start performance improvements which are then sustained by the system as a whole.

The next section of this report provides details, analysis and evidence from 5 country case studies (Tanzania, Sierra Leone, Punjab, Haryana and Ethiopia). Each of these case studies is structured as follows: