7 minute read

EXPERIMENTS

experiments in nature

For their weekend home in Spain’s western countryside, the founders of SelgasCano pair preservation with innovation

text: fred a. bernstein photography: iwan baan

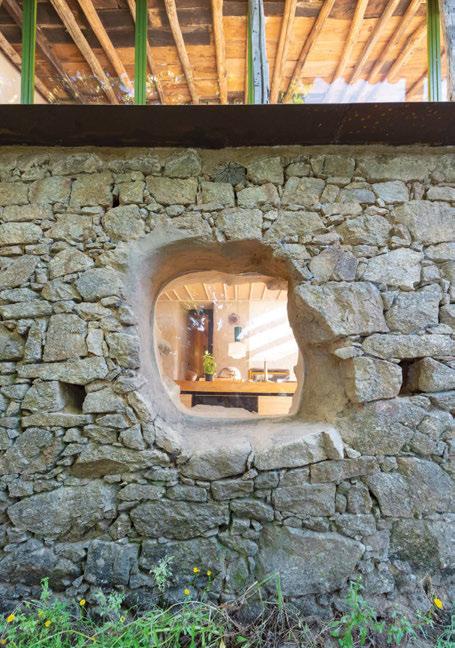

Previous spread: On a 12-acre former farm in Spain’s Cáceres province, four existing buildings and a newly built, yellow-doored guest house compose the weekend compound by and for the cofounders of SelgasCano. Opposite top: The masonry facade of the cottage has chiseled holes fitted with acrylic. Opposite bottom: The apertures bring light into the upstairs living area, where a 1950’s rattan sofa by Dirk Van Sliedrecht stands beneath planks from the cottage’s original firstfloor ceiling. Top, from left: Downstairs, the stone wall behind the kitchen counter has an irregular window opening handmade by Selgas and Cano. The couple also designed the hanging metal fireplace separating the living and dining areas. Bottom: Above the kitchen, with a cedar countertop, is the dining area, supported by a rebar structure. The married architects José Selgas and Lucía Cano have become known for their luminous buildings, mostly made from translucent materials in bright colors and bulbous shapes. These include Second Home coworking spaces in Los Angeles, London, and Lisbon, Portugal; a school in Nairobi; and rec centers and meeting halls throughout their native Spain. But the couple’s weekend house—decidedly rustic, with barely a smooth surface in sight—couldn’t be more different from those widely published projects. Does that portend a change in architectural direction for SelgasCano?

“We always try to work with what we find,” responds Selgas, reeling off a list of projects in which the couple used existing elements. In the case of the weekend house, in Cáceres province, a few hours west of Madrid, those elements included three farm buildings—a pair of chicken coops and a small stable for goats and donkeys—closely clustered around a rudimentary two-story cottage. The cottage didn’t have a source of heat—not a fireplace or even a chimney. When the previous owners would build a fire to keep warm, they did it on a stone in the middle of the kitchen floor, eventually blackening the woodwork overhead.

Over the four-year renovation, Selgas and Cano did install a fireplace and stoves, but otherwise they changed as little as they could. One of their main interventions involved lowering floors, by excavating, and raising ceilings to get a bit more headroom. “We can’t enter like chickens,” the 6-foot 4-inch Selgas says. But when the local contractors thought the ceilings should be 8 feet or higher, he demurred. A bit under 7 feet was enough, lest the character of the buildings be destroyed. “The existing scale was really nice.”

Still, where roofs were raised above the tops of existing walls, in the cottage and stable, there were gaps the couple filled with sheets of acrylic, giving the structures newfound

lightness. They also chiseled holes into some of the masonry walls, “to bring in additional sunshine,” Cano says. Acrylic was cut into panes that fit those irregularly shaped openings. Inside, while much of the woodwork and masonry were left in their natural state, some sections were painted white in order to bounce light around.

They added rooms within the existing footprint, mostly using salvaged materials, including some of the blackened wood from the cottage’s original first-floor ceiling. “It’s part of the history of the house,” Cano notes. Much of the design work was extemporaneous. The contractors, skilled as they were, weren’t comfortable working from plans. “So we typically would go there with them and say, ‘Let’s put a wall up to this height,’ and ‘Let’s install a wardrobe there,’ and then we’d choose the wood,” Selgas explains. He and Cano supervised construction together. And they did so forgivingly. The house, Cano says, “wasn’t meant to have perfect anything.”

The couple’s own bedroom, largely below-grade, had been one of the chicken coops. Its new roof is a concrete slab covered with soil and native plants. Puncturing a thick sidewall are two unusual windows. The first was made from a stump that one of the builders was saving for just the right project. The other was a kind of barrel, built to be installed a few degrees off horizontal. Selgas and Cano planned to use it to see mountain peaks, but the builders installed it upside down. “So now you see the lawn,” Selgas reports. “It’s almost like a piece of sculpture.” The other chicken coop and the former stable became the compound’s two guest bedrooms.

In the cottage, the original kitchen was pretty much open to the elements. “We kept much of that feeling,” Selgas continues. But he and Cano created a structure out of rebar to support the living and dining areas in the renovated upstairs. They also used rebar to frame the new stairway. And they broke a hole through the wall, “So the kitchen would have a relationship with the outside table, where we typically have dinner,” Cano says. Asked how they made the hole, she adds, “carefully and by hand.”

To complement the couple’s modern and vintage pieces by the likes of Monica Förster, Dirk Van Sliedrecht, and Hans Wegner, the builders made custom furniture on-site. “They have the time, the patience, to do things you can’t do in places where labor is

Top, from left: The guest-house roof is a chestnut-plank terrace with vintage deck chairs. A copper pipe feeds water from the property’s exisiting spring to the manmade swimming pond. Lined in local pine, the guest house has a wall that opens entirely and Hans Wegner’s AP71 chair beside an Italian vintage lamp. Its exterior began with an existing stone wall; one of the yellow steel doors leads to storage. Bottom: Verner Panton’s Ilumesa table joins a side chair by Alejandro Cano.

Top, from left: The former stable, entered through an original wood door, is now one of two guest bedrooms. Its bathroom has a vintage marble sink. Bottom: The primary bedroom, the former chicken coop and partly belowgrade, is also clad in pine planks, its sidewall punctured with irregular apertures and a reused midcentury fireplace. Opposite top: Some surfaces, such as a guestroom “headboard,” were painted white to reflect sunlight. Opposite bottom: Between the foreground stone wall and the cottage is the primary bedroom’s green roof.

expensive,” Selgas says. He said the price of the renovation was about $50 a square foot, or about $65,000 altogether—a fraction of what it would have cost in any major city.

After finishing converting the original buildings, Selgas and Cano decided they needed space to keep garden tools and patio furniture. An existing stone wall became one side of their planned storage building. They added the other walls, one of which is punctuated by yellow doors, and a wooden ceiling (made of the formwork from the project’s concrete pour)—perfectly adequate for a storeroom. Except that while working on it, Selgas says, “We noticed the incredible views and decided to transform it into a guest house,” albeit one that’s far simpler, spatially and structurally, than the main house. (A portion of this new structure was reserved for storage.)

Asked what she likes best about her family’s weekend compound, Cano answers, “It’s the setting. It’s nature.” That includes a rushing stream they use for swimming and an Eden of fig, olive, orange, and lemon trees. In fact, as the plantings around, and on, the house grow in, “The buildings are disappearing,” she says happily.

For his part, Selgas, an environmentalist, is particularly pleased by the project’s modesty. “Wasting space is a problem for our society,” he says. “We should only create what we’re going to use.” Like his and Cano’s gently upgraded buildings, he adds, “The future will be more about renovations than new things.”

PROJECT TEAM LUISMI QUINTANA: BUILDER. RUBÉN CRIBA: CARPENTER. PRODUCT SOURCES FROM FRONT CISAL: SINK FITTINGS (KITCHEN).