12 minute read

The Making of the Regiment

from 6 GR Journal 100

THE MAKING OF THE REGIMENT A PERSONAL VIEW

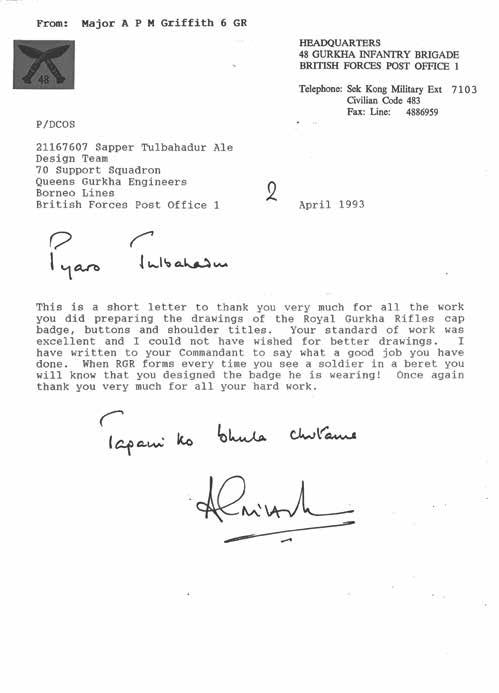

On 10 September 1994, in a parade two battalions. To avoid prolonged litigation, and attended by the Great and the Good the awakening of old sores, the full story of the (or at least by the Prince of Wales formation will have to wait until certain persons are and the Chief of the General Staff, dead (you cannot libel the dead) for the process of with many other lesser but still exalted personages) formation brought out the very worst in some of the the Royal Gurkha Rifles was officially born, and 6th so called Old and Bold, more accurately Middle Aged Gurkha Rifles, along with the 2nd, 7th and 10th Gurkha and Timid, who despite having left the Brigade and Rifles ceased to exist as active units. It or the Army many years previously, or in was probably the most magnificent some cases hardly served in it at parade that any Gurkha unit all, somehow thought they were (or any British unit, come to entitled to tell the modern that) had carried out for army how it should go many a long year: the about its business. majority of the entire year’s supply of the It was the then UK Gurkha battalion’s Brigadier Brigade of blank ammunition was Gurkhas, Christopher expended in practising Bullock, who detailed for the feu de joie, and me for the job. I was the Battle of Britain not keen: the thought Flight flew low over the of sending my friends on parade ground in Church redundancy did not appeal, Crookham as it was being but I was told that I had the fired. In practice the merging job because I was senior in of the various elements of the new service (albeit not in rank) to most regiment had happened piecemeal The Badge and Shoulder Titles of the British Officers at regimental during the previous months; the (over page) of the RGR drawn by duty, was known to all the Gurkhas parade, and the jollification that Sapper Tulbahadur Ale, and trusted by them. This was of ensued after it, was only the official Queens Gurkha Engineers course a blatant appeal to my overrecognition of our emergence on the inflated ego and I moved initially ORBAT of the much reduced British Army. to Cassino Lines in the New Territories of Hong Kong and then to the Prince of Wales Building on Hong Now, at the time of writing, no British Officer Kong Island, although knowing what the standards of currently serving in units of RGR was serving when the latter’s officers’ mess was like I lived with the 2nd the regiment came into being, and many of the Gurkhas in the New Territories and commuted daily. Gurkha Officers were but riflemen or junior NCOs, so it may be apposite to pen a few words about The reason for the savage reduction in the Brigade, how we came into being. I make no apologies for and the not quite so savage reductions in the wider writing this as a personal memoir, for I was detailed army, was the incurable optimism of our politicians. as the Formation Officer, charged with merging As serving officers we rarely came in contact with the five battalions of the four infantry regiments these beings, but the aim of a politician – any of the Brigade into one regiment of three and then politician – is to get into power and once there to

stay there, with all the access to turtle soup and the means to do favours for unsavoury friends while lining their pockets in so doing. To get into power and to stay there requires the bribing of a greedy and ignorant electorate which wants instant gratification and is only interested in those things that affect it directly. To do this, politicians take money away from things that do not impinge upon the everyday life of the mob, and spend it lavishly in an effort, usually successful, to garner votes. An obvious source of extracting money is the Defence vote, four percent of GDP when I went to Sandhurst in 1960 and just two percent now – although even this is a fudge as it includes my pension, and splendid fellow that I am I can hardly be described as contributing to the defence of the realm. With the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, bankrupt and with a command economy that did not work, the Cold War was over, and politicians seized the chance to spend what they called the ‘Peace Dividend’. There were to be reductions right across the army but the severest were to be to the brigade: a seventy-five percent cut in manpower, from nine major units commanded by lieutenant colonels to two with the infantry reduced from five battalions to two and the corps units from three regiments to three squadrons.

For the infantry the first point to be addressed was whether to create one regiment by merging the four existing ones, or whether to retain two regiments, with each having one battalion. I was not involved in this discussion, although my personal preference was to disband the junior Western and the junior Eastern regiments, 6 GR and 10 GR, with 2nd and 7th Gurkhas remaining. My reasons were that politically it would be more difficult to disband a regiment than a battalion of a regiment, and that it would negate all the arguments about dress. In fact the Council of Colonels decided that one regiment, The Royal Gurkha Rifles, would be formed, its cap badge being ‘crossed kukris points uppermost cutting edges down the whole surmounted by an imperial crown’. A hasty adjustment put the left kukri over the right, otherwise the other way round would have been the badge of 6 GR less the figure 6.

The first problem was that the establishments of the UK Gurkha battalion, the Brunei Gurkha battalion and the remaining Hong Kong battalion were all different, which made the number crunching needed to ensure that redundancy was to be equal pain across the whole brigade, regardless of cap badge, exceedingly complicated. Fortunately the officer responsible for the actual calculations was the highly competent and experienced Major Paul Gay, 7 GR, who manged to juggle redundancy and inter regimental transfers in as fair and equable a manner as it was possible to be. Once the final establishments had been decided upon the various appointments could be filled. The first merger was of the two battalions of the 2nd Gurkhas, relatively straightforward as it involved no changes in dress or recruiting areas, although there were certain inter regimental transfers in keeping with the principle of equal suffering for all. The process of setting up the new regiment was the prerogative of two committees, the Advisory Committee consisting of the Colonels of all four existing regiments, and the Executive committee consisting of the commanding officers of the existing battalions chaired by the Formation Officer (me).

Some questions were relatively easily resolved: regimental funds followed the soldier; regimental silver could be distributed to the eventual battalions of RGR and it was decided that we would furnish our messes in UK and Brunei and then leave the property in situ, rather than having it moved half way round the world every three or four years. One major issue arose when it was necessary to reinforce the Belize garrison with a jungle trained battalion and the Ministry of Defence directed that this should be the 2nd Gurkhas from Hong Kong. This was a time when other than in UK Gurkha soldiers were paid very much less than British soldiers doing the same job (although Gurkhas

did not pay income tax, National Insurance or for food and accommodation). Gurkhas were accustomed to a tour in Belize but this had always been carried out by the UK battalion and the men were thus in receipt of UK rates of pay. When the penny pinching bean counters of the MOD decided that in Belize the battalion would remain on Hong Kong rates of pay without the Belize LOA admissible to British troops, it was apparent to all that this was simply not fair, a situation swiftly remedied by the then Brigadier BG, Brigadier Mervyn Lee, in a feat of creative accounting about which the less said the better.

I had been careful in all my decisions to keep everyone informed. I visited all the battalions regularly and spoke to BOs, GOs and Sergeants messes, explaining that nobody was going to get what they would ideally like, but all would get what they could live with. I emphasised that we must think as a Brigade, and not as representatives of individual regiments. One matter for discussion was whether one of the eventual two battalions of the new regiment should be made up of men from the East and the other from the West, or whether all should be mixed, as was the case with the Corps regiments, soon to be squadrons. Talking to Eastern GOs and men it was soon apparent that they were concerned that if we were mixed, and now that promotion was in the hands of external boards, rather than the prerogative of the battalions, as in the past, the westerners would get all the promotions because ‘they are cleverer’. They are not, of course, cleverer, but education is more easily available in the West than it is in the East, and so promotion exams might be less of an obstacle to westerners. Whatever the truth, if that was the perception, firmly and honestly held, then we should accept it and retain one battalion from the West and the other from the East.

There were, of course, some stumbling blocks. One colonel of a Gurkha regiment was also the colonel of a British regiment due for amalgamation. He wrote an impassioned letter to the Times and Telegraph bemoaning the loss of his British regiment, but not a word in support of Gurkhas. Fortunately he had been replaced by the time that I had to deal with the Council of Colonels.

All was going swimmingly until we came to the matter of dress and accoutrements. I had laid down, and had it agreed by commanding officers, that all that was historically significant would be carried forward, but that we must avoid looking like walking Christmas trees. One thing I wanted very much to carry forward to the new regiment was the ‘lale’ then worn by the 2nd Gurkhas. This embellishment stemmed from the actions of the Sirmoor Battalion (later the 2nd Gurkhas) at the siege of Delhi during the Indian Mutiny of 1857/58 and it was this action that brought it home to the British that Gurkhas were rather more than just another martial race. Serving officers and men, when its origins were explained, accepted this, and then the shitstorm started. I had heard on the grapevine that one long retired lieutenant colonel, now dead, intended to write an article in his regimental magazine attacking the adoption of ‘lale’ by the new regiment. I waited until evening in Hong Kong, morning in UK, and rang him up. I explained that the whole matter of dress was delicate and if he published his article it would not be helpful. ‘Your problem, Gordon, is that you are well disposed towards the 2nd Gurkhas’, he said. ‘I am well disposed to all Gurkha regiments’ I replied. ‘Well, we were brought up to hate them’ said he. Fortunately, a swift fax to his editor ensured that his article was not published. In the event historically ignorant and dinosaurian objection from outside the serving body was such that the adoption of ‘lale’ had to wait until the new regiment came into being, when it was swiftly incorporated.

We had agreed that the metal shoulder title should be black ‘RGR’ and then some bright spark on the Council of Colonels (AKA the Advisory Committee) thought it would be rather good to have a bugle horn affixed to the top of the RGR. I explained as diplomatically as I could (which was not very) that this risked being mistaken at a distance for the Royal Green Jackets, whose shoulder title was a black RGJ with bugle horn, and that in any case my observation had been that the bugle horn tended to break off. In a rather bad-tempered signal from the Advisors I was

nevertheless ordered to amend the shoulder title to incorporate a bugle horn and thus I submitted a case to the Army Dress Committee. Fortunately, I had a chum on the aforesaid committee and a swift telephone call ensured that the request was turned down.

The Regimental tie took longer to resolve. The colours had to be a combination of black, rifle green and red, but it had to be different to any other with the same combination of colours, and there were, somewhat to my surprise, a great deal of such ties, cravats and cummerbunds ranging from the Ceylon Light Infantry through the Rhodesian Light Infantry to the South Irish Horse and , if one went back far enough, to the Chasseurs Brittanique of the Peninsula War. It was decided that a feminine input was required, one with some artistic talent, and Captain Jean Erskine, then the Staff Captain ‘A’ in HQBG was presented with an array of combinations, none of which had, as far as we could tell, been used before, and she chose the tie that we wear today.

The regimental marches, Double, Quick and Slow, the latter only used at funerals, had to be playable by the band and by the pipes and drums, as it was decided that each battalion should have pipes and drums, rather than a bugle platoon, although drummers would be dual trained. Not all marches can be played by both, and eventually it was decided that the Quick March would be ‘The Black Bear’ pending the writing of a new regimental march (which has since been done – ‘Bravest of the Brave’).

At last, after much fencing with dinosaurs various, all was agreed and 1 July 1994 was set as the day when the new regiment would come into being, with all ranks of units of the four constituent regiments adopting the cap badge and dress of the Royal Gurkha Rifles. As the date approached the promised supply of cap badges for Hong Kong had still not arrived. Signals to the supplying ordnance depot brought the suggestion that the 6 GR cap badge with the 6 removed might do until the real thing arrived. Clearly this was not acceptable and at last a somewhat peremptory signal to the Director of Ordnance Services in the MOD got a chilli inserted up somebody’s bottom and the badges arrived at Kai Tak the day before formation. I and my wife (on leave from Germany) spent the day driving round Hong Kong delivering the requisite number of cap badges so that on the following day all could wear the badge of the Royal Gurkha Rifles.

And so the Royal Gurkha Rifles was officially born.