5 minute read

PAWAN DHALL: A MILLION

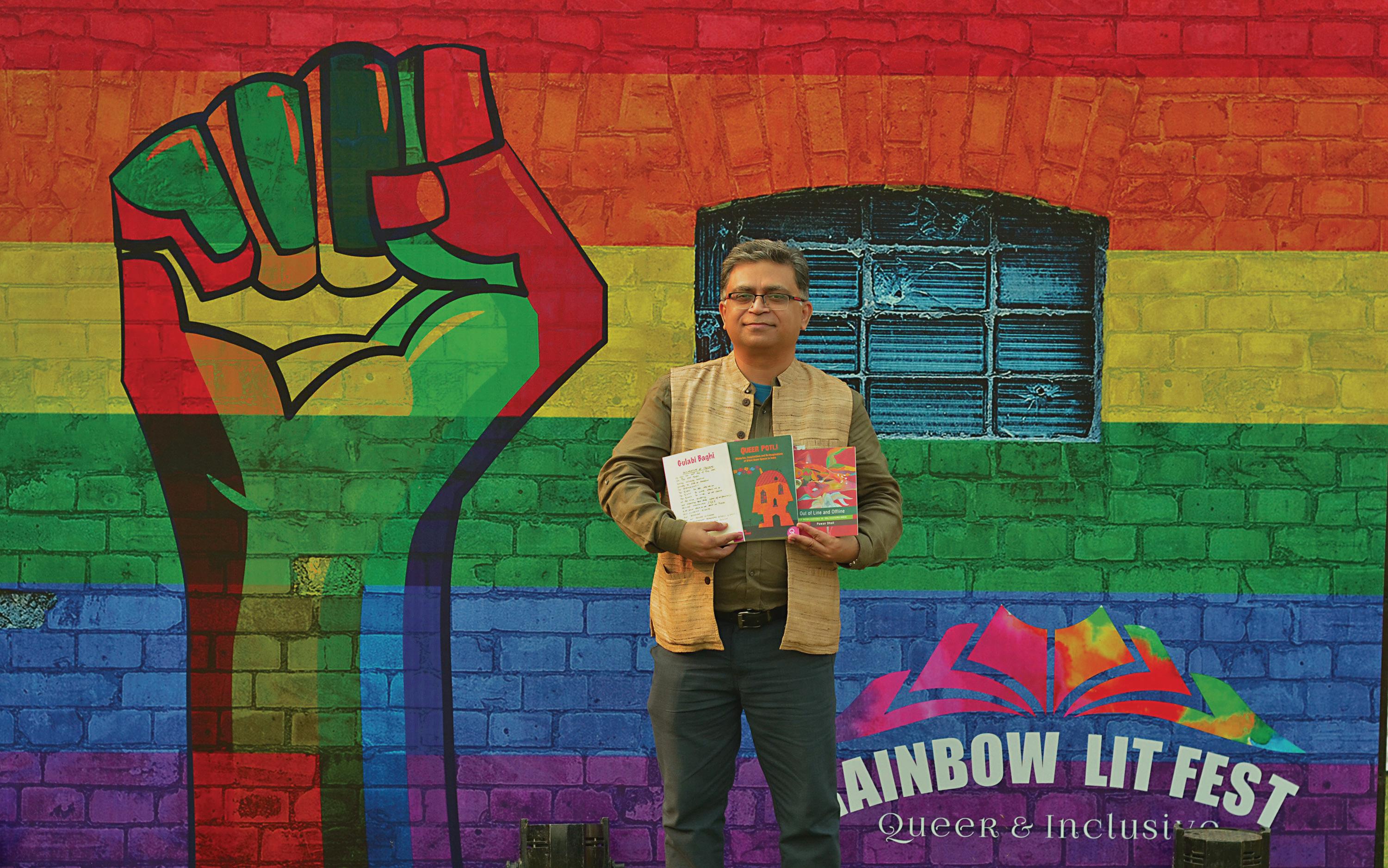

PAWAN DHALL: A MILLION ACTIVISTS NOW How LGBTQ pioneers kickstarted a movement in India By Paul Gallant

When I arrived in Calcutta in 1995 (it was renamed Kolkata in 2001), I was backpacking around India with an American lesbian who was making a special effort to meet gay and lesbian people there. Emphasis on “effort;” this was pre-mainstream internet in a country that had virtually no “out” queer life, no institutions like bars or community centres or chat lines. My travel companion had obtained (I have no idea how) the mailing address of Counsel Club, a Calcutta support group founded just two years earlier. Through a series of mailed letters, using “general delivery” post while moving from city to city, she had, astonishingly, set up a meeting with the club’s founders. I joined her for the rendezvous at a restaurant on Park Street. My memory was that there were three or four guys (I think the membership at the time was four or five), whom my female companion questioned rigorously about their lives, the organization and how she might meet openly queer women (I don’t think she ever did in India). It was her time, and I was young and shy, so our conflab ended with exchanged addresses, with the club members not even knowing if the quiet Canadian was gay or not. I was, and kept in touch with one of that little group of pioneers, Pawan Dhall, who has been a key force – self-effacing, philosophical and pragmatic – in so much of the progress made since then for queer people in eastern India and beyond. The narrative of Dhall’s new book, Out of Line and Offline: Queer Mobilizations in ’90s Eastern India, starts just before that quirky little meeting, and features interviews with many of the people who played a part in the changes in attitudes – of queer people, straight people, governments, media and other institutions – that have happened over the past 27 years. “These are microhistories that fit into the larger history,” Dhall tells me. “I wanted to do something long-lasting and bring out stories from the past, because for a whole generation of people, queer activism in India began some time after the internet arrived.” At the time we first met, same-sex sexual-romantic relationships – and talk about them – happened behind closed doors or maybe in parks late at night, where a stranger asking, “What time is it?” was the most audacious proposition a gay man might ever hear in public. If the police stumbled into a queer moment, they were likely to threaten blackmail for money or sexual favours. Public discussion of HIV/AIDS was a non-starter. “There was a real pentup need for people to connect,” says Dhall. Counsel Club started as a support group – and as a side effect, a way to find sexual or romantic partners – but gradually became a lab for more ambitious endeavours. The club’s membership peaked at around 300 dues-paying members, but its activities brushed up against thousands of people. Dhall went on to found Varta Trust, a non-profit that publishes advocacy about gender and sexuality, and was one of the organizers of the 1999 Friendship Walk, which became Kolkata Rainbow Pride Walk, the first-ever such walk in India and Southeast Asia. At the most recent march, last December, hundreds of people participated – and except for maybe 10 of the original participants, “everyone else was a stranger to me,” says Dhall. Cracking open the door Kolkata is the capital of West Bengal and people in that state, Bengalis, often consider themselves more progressive than other Indians – Bengali-language media became more positive about queer issues more readily than Hindi-language media – so advances tended to happen more quickly than in many other Indian cities. Even in the 1990s, there’d be hijras (a distinctly Indian identity loosely analogous to trans) in the city and rural areas who would host open houses where same-sex co-mingling occurred. By the early 2000s, the internet and the liberalization of the Indian economy brought more Western ideas about homosexuality, trans identity and queerness. Conservatives argued that India’s “innocent little culture” was being corrupted by foreign influences, but there was probably an even stronger growing interest in India’s own long history of queerness: same-sex references in the Kamasutra, queer characters in the epics and mythology. The 1996 film Fire, a lesbian-romance tearjerker by Indo-Canadian director Deepa Mehta, also ignited a sometimes-nasty debate that ultimately opened some people’s minds about queerness. Through all this loomed Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. Enacted during British rule of India, the law made all same-sex activity illegal. Seldom used except for police harassment and blackmail, it not only kept people in the closet, but prevented the establishment of LGBT-oriented businesses and organizations. In

2018, the country’s Supreme Court ruled Section 377 unconstitutional “in so far as it criminalizes consensual sexual conduct between adults of the same sex.”

It was a tremendous legal victory, but it would be an exaggeration to say that the ruling has transformed Indian society in the past year and a half. The police still blackmail gay men and harass trans people. Out people still lose their jobs. Queer women are still largely invisible. But Dhall says the end of Section 377 has created more opportunities for people to come out at work, to be open about their relationships, to create community and to bring discussion of queer issues to schools and universities. Homophobia from educators and community leaders has come under more scrutiny. In Mumbai and Bengaluru (which people still tend to call Bangalore), entrepreneurs have launched businesses that consider the needs and tastes of LGBT customers.

Dhall is less interested in whether Mumbai, Bengaluru, New Delhi or Kolkata might the first to get a rainbow-festooned gay megaclub than whether better health services can now be made available. Same-sex marriage is way down his long list of priorities.

Dhall’s day job, when I met him, was as a newspaper editor. And it’s words and ideas he’ll be wielding as weapons as he enters his third decade of activism.

“You don’t have the choice to find the energy. You still have to keep your head above water,” he tells me. “I’m more focused on writing now, to preserve the history. Fortunately, I don’t have to worry about a whole lot of things. There are many other people now doing the work.”