9 minute read

THE HISTORY OF THE (Super-Gay) (Super-Gay) InternationalMale CATALOGUE

A look back at the unusually fashionable history of the groundbreaking mail-order catalogue

By Christopher Turner

For countless gay men who grew up during a slightly earlier era, the glossy International Male mail-order catalogue was like nothing that had come before it, providing a portal to both fashion…and fantasy. Between the time it launched in the mid-1970s and its closure in 2007, this one publication helped to shape the image of masculinity and menswear, especially for gay men.

The pioneering publication had an early tagline of “Freedom for the man,” and styled itself as a catalogue-slash-magazine that was filled with ripped, muscled bodies wearing seemingly out-of-reach fashions, sexy swimwear and skimpy underwear. International Male treated men as objects of desire, with its subtly suggestive all-male photography layouts. But given the profound stigma in that era about homosexuality (it was only removed from the American Psychiatric Association’s list of psychiatric disorders in 1973!), it was never advertised as a gay publication, even though it was recognized as exactly that as it gained popularity.

Still, the catalogue became a North American phenomenon and was a massive success, raking in over US$100 million at its height in the 1990s, and hitting three million homes with its quarterly mailers before it finally shut down.

It’s safe to say that a large number of International Male’s young readers never bought anything from the catalogue, but nonetheless it played an important role in the sexual awakening of many of those readers with its somewhat coded homoeroticism. The catalogue also had a broader cultural impact: it was ahead of its time in the world of men’s fashion, inspiring fashion trends ahead of the mainstream, and it inadvertently kicked open the doors for the future of sensual “sex sells” advertising campaigns filled with chiselled pecs and abs.

Today, many will reflect back on the mail-order clothing catalogue as “Victoria’s Secret for men.” And, yes, like that famous lingerie brand, International Male sold a lifestyle in addition to offering plenty of fodder for sexual fantasies – but it was much more than that. Here’s a look back at the rise and fall of one of the originators of the mail-order boom: the super-gay-but-not-gay International Male mail-order catalogue.

In the beginning

The origins of International Male go back to 1968, when formerly closeted US Air Force veteran Gene Burkard returned from Europe with a desire to bring a little of the continent’s fashion home with him. While he was in London, Burkard had seen a suspensory (a bandage-like medical garment intended for men with hernia problems) in a shop window and thought it could be redesigned as men’s underwear. So he purchased one from the medical store, weaving his way through the incontinence items and back braces, and brought it back to San Diego. There he hired a pattern maker to modify it and turn it into the “Jock Sock.” It was sort of a quasi-jockstrap, minus the strap…just a colourful cup to hold everything together in the front.

Burkard was pretty familiar with the marketing opportunities magazines offered – prior to the army, he had worked as an advertising copywriter at the Milwaukee Journal – so after he created the “Jock Sock” in 1971, he began marketing the men’s underwear in a range of colours in the back pages of The Advocate and the Los Angeles Free Press. He then developed a national advertising campaign and managed to overcome resistance to seemingly gay advertisements by appearing in such publications as the Los Angeles Times, Playboy and Penthouse magazines.

The orders started rolling in.

In 1974–75, Burkard incorporated his operations under the name Brawn of California and moved production into a factory with 40 sewing machines producing 22 different items. In 1977, he officially opened an underwear and loungewear brick-and-mortar store, also called Brawn of California, which was located in San Diego at 2802 Midway Drive. He sold swimwear and was determined to change the way that most men perceived loungewear: rather than oversized silk pyjama sets and tacky leopard-print briefs that were mocked in the mainstream, he envisioned something truly sexy, like subtly revealing underwear, thongs and jocks. It took off, and the following year he opened a second store in West Hollywood located at 9000 Santa Monica Blvd.

But the company’s success really jelled when Burkard began mailing catalogues that invited men to order (and wear) whatever they wanted.

Early on, Burkard had recruited a secretary to help him bring the company to the next level. This woman, Gloria Tomita, would go on to help him shape the International Male catalogue. Tomita had an eye for what fit perfectly on the male body, while Burkard dealt with the fashion angle. Together they put together a ragtag staff that consisted largely of gay men and straight women who acted as fashion designers, art directors and salespeople. The environment was, at best, essentially an “all hands on deck” situation where the salespeople were helping design clothes, art directors were helping sell, etc. But it worked.

Burkard realized early on that he could reach a gay male audience by putting flamboyant clothes on ultra-masculine male models. In his mind, the clothes would be a more fashionable alternative to the traditional grey suit that every man seemed to be wearing, and the models would be fun to look at, too.

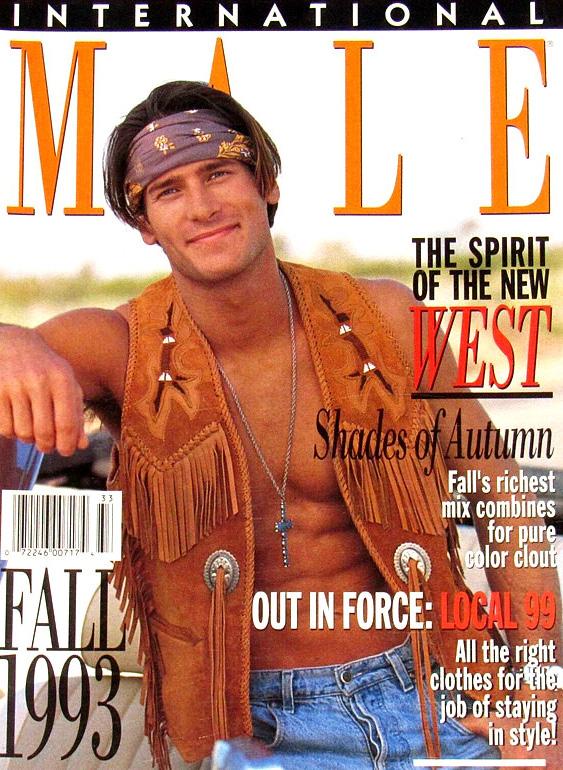

In 1976, the very first International Male catalogue hit the mail, filled with magazine-style spreads showing what Burkard thought of as fashion-forward threads. He wanted to promote the image of virility and a lifestyle of good-looking men who were leading exciting lives in exotic international settings. From its initial issue the catalogue featured flamboyant clothes, including wild-patterned shirts, frilly shirts, body-hugging knitwear, military-inspired gear, mesh tank tops, rugged khakis and, of course, skimpy bikini underwear, all modelled by handsome, mostly heterosexual, white models with chiselled jaws and muscled bodies. The paragons of masculinity.

The clothes were meant to appeal to both gay and straight men; however, the images were borderline homoerotic from the start, and the catalogue was among the first non-pornographic publications to focus on men’s bodies – often in a blatant, sexually charged way.

“We never said we were a gay catalogue, but gays ‘got it,’” Burkard said in All Man: International Male Story, the feature documentary debut of Bryan Darling and Jesse Finley Reed that had its world premiere at the Tribeca Festival in 2022. (The filmmakers interviewed Burkard before his passing on December 11, 2020.)

“I mean, gays looked at it and said, ‘My God, that’s me, and I can get this in the mail because it’s not saying gay anywhere.’”

“International Male really capitalized on putting masculine guys in pretty not masculine outfits,” notes fashion expert Carson Kressley, who also appears in the All Man documentary. “The very start of the metrosexual movement – where you can wear clothes just to have fun.”

How did I get this?

For gay men who came of age in the late 1970s through the early 1990s, hiding the International Male catalogue, which somehow seemed to magically appear in the family mailbox, became something of a rite of passage.

When people recall receiving their International Male catalogues in the mail, “How did they get my name?” is arguably the number one question that follows. The answer is actually pretty simple: the company bought mailing lists. Thanks to customer lists purchased from magazines like GQ and Playboy, and even mail-order music club Columbia House Records, International Male built their own mailing list, after narrowing down the purchased lists to the demographic they were going after: young men, especially if they were in their 20s and 30s.

In the beginning product orders had to be phoned in, as no online database existed at the time, so whenever a new issue was imminent, the phones would be ringing off the hook. As time went on, it eventually became necessary to computerize the entire ordering system.

Of course, gay men were by no means the catalogue’s sole – or even primary – target audience. Ultimately, a lot of the unknowing subscribers were straight, and according to Burkard as well as previous International Male employees who have been interviewed throughout the years, a lot of the catalogue’s customers were actually women buying clothing from the catalogue for their men. Some former employees have gone as far as to say that 75 per cent of buyers were women shopping for their significant others, trying to get their boyfriends and husbands to swap their boring beige Dockers khakis, polos and white Hanes briefs for something more adventurous.

Shaping the image of masculinity and menswear

Even if a large percentage of the actual customers were straight (or closeted), it’s hard to deny the impact the catalogue had on young gay men across North America, or the confusing layers of masculinity that the magazine presented: straight guys wanted to be the models, and gay guys wanted to have sex with them. This is how International Male managed to find a wide audience, which also led to the magazine getting a reputation of a gay magazine. After all, as influencer William Graper notes, the “Adonis” bodies on display weren’t the revolutionary part. “What was interesting about that was the flamboyance of the clothes that were then put on that guy.”

By combining fashion and masculinity, International Male unintentionally (or even intentionally) spoke to many and helped put its idea of the perfect male physique into the general consciousness. Its admirers included everyone from Calvin Klein to movie and theatre costume designers looking for threads as well as inspiration and ideas.

The catalogue also helped launch careers. Over the years, many now-famous models and actors posed in their early careers for the catalogue. Pre-stardom models included the likes of Shemar Moore, Kevin Sorbo, David Chokachi, Cameron Mathison, Charles Dera, Christian Boeving, Gregg Avedon, Rusty Joiner, Brandon Marcel, Scott King, Brian Buzzini and Reichen Lehmkuhl.

Promoting the Adonis body type wasn’t new in itself, but the idea of putting flamboyant clothes on a hunky male model was, and the appeal of International Male was largely lowbrow, appealing to working-class men who dreamed of dressing like a dandy living a fashionable and fun life of leisure. And that’s what sold the apparel…and provided imagery that many gay men would ultimately fantasize over.

Something not considered at the time? The damaging effects of insinuating into popular culture the idea that this was how all male bodies should look, or the fact that the catalogue used very few models of colour.

The magazine gained popularity in the mid ’80s and early ’90s, coinciding with the onset of the AIDS epidemic, and the escapist fantasies of International Male suddenly seemed out of touch with the grim realities of that time. The predominantly gay male staff of the catalogue was hit by the AIDS crisis that ravaged North America, and a number of them died from disease.

The beginning of the end

Eventually, Burkard was approached to sell his growing business. In 1987 he retired and sold International Male to Hanover House, a giant conglomerate based out of Hanover, Pennsylvania, that was doing big business with Middle American mail-order catalogues. They had big plans for International Male, and began to take it mainstream shortly after the deal was finalized.

Of course, being managed and produced by a more conventional company meant big changes…and by the early ’90s, there were lots of them. Hanover House wanted to make the catalogue sexy but not sexualized, and wanted a broader demographic of subscribers. They recognized the gay customer base and wanted to keep it, but also wanted to expand the catalogue/magazine. They did. It grew to an enormous extent.

The early 1990s saw the expansion of the International Male business under Hanover Direct as Versace-inspired men’s fashions from Europe reshaped the demand for menswear in North America. There were even attempts to hire heterosexual photographers, to pair the hunky male models with women and to tone down the clothes and the homoerotic images. But as International Male found its mainstream image working, it began to lose the interest of its old gay customer base.

As the magazine continued to expand, it received its fair share of backlash and was often dismissed as a gay rag, famously being skewered in a 1993 Seinfeld episode about pirate shirts (the Season 5 episode “The Puffy Shirt” originally aired September 23, 1993). And in the 2003 comedy movie Zoolander, a notable scene featured Derek Zoolander (Ben Stiller) on the cover of International Male, while another memorable mention came during a heart-to-heart between Zoolander and an equally vacuous male model rival, Hansel (Owen Wilson). “Your work...in the winter International Male catalogue... made me want to be a model. I freakin’ worship you, man.”

The final nail in the coffin came when regular retail department stores began selling edgier menswear, and the importance of International Male rapidly declined. It hung on for a few years, but by 2007, the International Male fantasy was over and the last paper catalogue was mailed out.

The catalogue may be gone, but what it inspired is very much a part of men’s fashion and how using sex can sell men’s apparel. Love it or hate it, the groundbreaking mail-order catalogue set the gold standard for fashion and desirable bodies for gay men since the mid-70s.

In desperate need of a little glossy nostalgia? If you don’t have any old issues of International Male lying around your basement, you can easily search them out on the internet. A quick scan of eBay shows hundreds of issues up for grabs

As for a return to the glory days of International Male? The fantasy is long gone…but keep watching the mail, just in case.