6 minute read

MY SISTER’S HAVING MY BABY

A personal tale of family, surrogacy, and access to fertility care for LGBTQI+ intended parents

By S. W. Underwood

I’ll carry a baby for you.

Words that seared through the ambient noise of children chattering in boisterous play. Words that slipped through the cracks of a wall built to defend from the agony of my inability to carry my own child. Words spoken by Meghan, my baby sister and now a mother of five of her own children.

Words are not often elusive for me. I’m a writer, a teacher and a researcher: words are my trade. Yet I sat in silence for minutes, I don’t know how many – vibrations tingling like electricity through my nervous system. Did I hear her right? Was this a joke?

But she was serious. Very serious. She’d carried five babies through three pregnancies (the last a blessing of three!), and now she was done – done with her own babies, but ready to help me with mine.

What motivates my sister to help me and my partner create life is hard to capture in writing. And I know that trying to understand the depths of this gesture of love, this gift of life, will be an unending project I experience until my last days. Often when I tell this story to friends, colleagues and strangers, their eyes swell with reverence at the lengths people will go to demonstrate their love. Their faces swell with the promising hope of a thriving community of LGBTQI+ parents, empowered by the communal compassion of incredible women like my sister.

In these moments, I try to sit with the joy my sister and I are creating in other people – one we experience ourselves, of course. I try to breathe in their romantic reflexes and impassioned notions of what happens next.

To most people, the announcement of a pregnancy is the beginning of a journey, the start of a path travelled by ancestors immemorial. You can imagine, then, the weight of sharing what happens next.

Achieving pregnancy with a gestational surrogate woman in Canada is not easy. While legislation in Canada makes surrogacy legal, it must be altruistic. This means that you cannot compensate a surrogate or egg donor, though there are still fertility- and pregnancy-related expenses that can be costly, typically between CAD $40,000 and $80,000. In some provinces, subsidies are available for the first

round of in-vitro fertility treatment. For example, in Ontario where I live, the Ontario Fertility Program (www.ontariofertility.ca) offers a one-time reimbursement for fertilization and embryo transfer into a surrogate carrier. In our case, this would cover about $10,000 worth of expenses.

This would be a modest help in an otherwise costly experience for us, to be sure, but my sister and I are not eligible for this subsidy: the funding is available only if the surrogate carrier has her own OHIP coverage. My sister lives in British Columbia and no such program exists under the B.C. Medical Services Plan.

Finding a fertility clinic is no easy task either. While groups like Health Canada, the Canadian Fertility & Andrology Society, and provincial physician colleges regulate fertility medicine across the country, practice varies from one clinic to the next. Because my sister has five young children, we thought it best to find a fertility clinic near her. Yet, at each of the Vancouver fertility clinics where we sought medical help to begin this journey, we were devastated to be turned away at the door.

Fertility clinics develop a model profile for the surrogate carrier, including an age range, that she has been pregnant before, that she is not a dependent alcohol user, and so on – the kinds of things you would expect. But they also specify a body mass index (BMI) range. My sister, recently having given birth to triplets, met all criteria except BMI. Specifically because of this, clinics in Vancouver would not support us in our pregnancy journey.

Shut out by fertility clinics in Vancouver, we turned to Anova Fertility in Toronto, where we became enamoured with Dr. Marjorie Dixon, whose compassion, intelligence, and commitment to women’s health and LGBTQI+ people creating families uplifted us. She affirmed that my sister’s commitment to building a family with us was an existential treasure – a gift she would help us realize. Dr. Dixon reasoned that although my sister’s BMI was not in the ideal range, it was only one aspect of her health – one we would empower her to meet.

I appreciate that she immediately and sensitively recognized the social, cultural and economic context we bring with us. She demonstrated a clear understanding that LGBTQI+ people have real challenges: when intended parents like my partner and I come looking for medical help, it’s not going to be easy for us to immediately meet all the criteria for intended parents and their surrogate carrier (my sister, in this case). Rather than turning us away because we were not perfect candidates according to the standard guidelines, she promised to work with us, to work with my sister, to empower us to succeed on this fertility journey to parenthood.

“Personally, I am deeply familiar with what it means to be marginalized. I am a Black, female, LGBTQI+ CEO in the medical realm,” explains Dr. Dixon. “I founded Anova because, as both a physician and an IVF [in vitro fertilization] mother myself, I recognized a gap in access to care, and so made it our mission to stand for all Canadians looking to grow their family. Each journey to parenthood is unique and should be treated as such; guidelines are in place to ensure quality care occurs – but we must acknowledge that they aren’t one size fits all.”

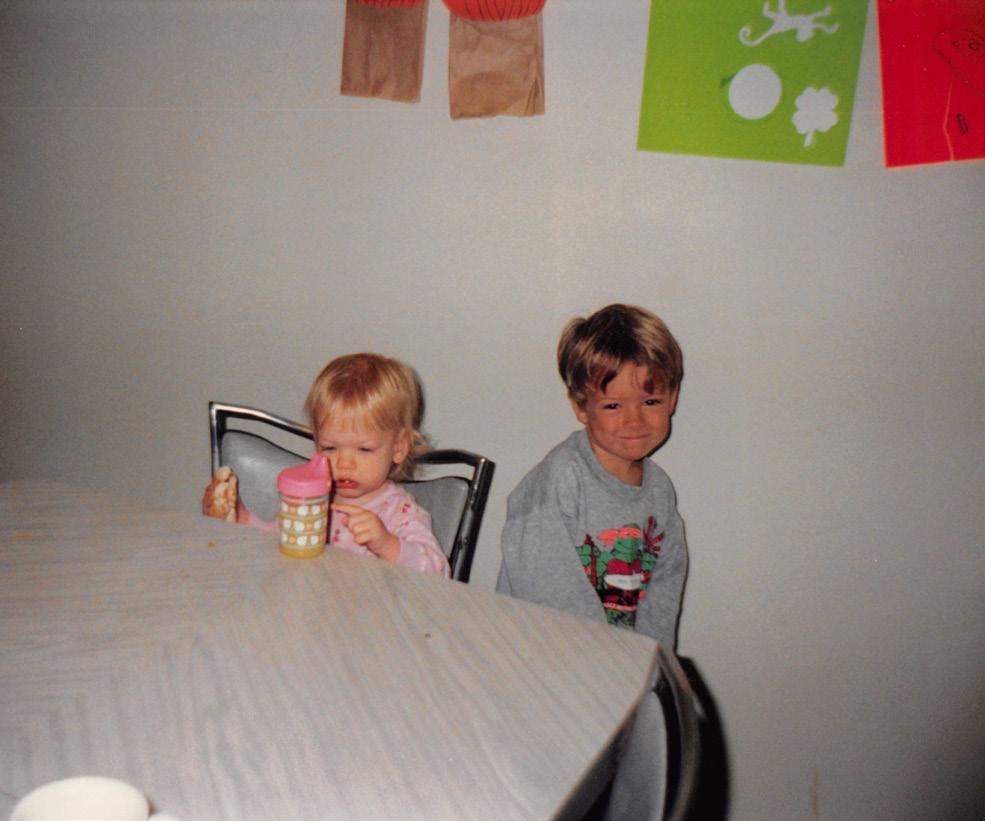

The author and his sister Meghan as children.

In addition to this sympathetic dedication from Dr. Dixon, we were comforted by the warmth of the clinic staff, their competent and earnest commitments to LGBTQI+ family planning, the confidence and expertise of the medical care team, and the breadth of knowledge about third-party programs (especially egg donor agencies, surrogacy agencies and legal firms).

Today, we wait for the COVID-19 pandemic to run its course as our fertility treatments remain paused, the effects of COVID-19 on embryos and pregnant women unclear. While I wish to tell my audience that the obstacles end here, we were slowed again by further complications entirely unrelated to the biology of reproduction: soon before the pandemic hit, Health Canada changed its regulation of frozen oocytes (ova/eggs) imported from other countries. While this was done to ensure that the treatment of donors was safe and their quality of care high, it has been a source of delay for people like us who were mid-journey. A year before this, through an agency and under medical guidance, we had selected 12 frozen oocytes from two donors in Eastern Europe at a cost of about CAD $13,000. While we intended to combine these with our sperm to create embryos, the new regulations created bureaucratic complications that have yet to be resolved.

Variation in clinical practices and commitments to LGBTQI+ family creation, limited funding opportunities, and even unforeseeable viral pandemics are just some of the obstacles we have had to navigate on our journey towards parenthood. As a community, Canada should work hard to reduce the financial and institutional burdens on all intended LGBTQI+ parents. It’s not the least we can do: it’s the best we can do.

At night, I sit in the quiet of my garden, seeking wisdom in the steady movement of life all around me. In the darkness, I see my sister’s smiling face as she mouths the words, I’ll carry a baby for you. I practise patience, believing that one day, I will hold my baby in my arms – a baby my sister will labour to bring into this world. Let us honour her courage, her thriving devotion to love, and her compassionate investment in life itself. Let us be the best we can be, just like my sister.