6 minute read

GURL, YOU BETTER SPEAK THE

GURL, YOU BETTER SPEAK THE QUEENS’ ENGLISH

By Paul Gallant

About a decade ago, I received a copy of The Dictionary of Homophobia, an English translation of the hefty French reference book written by Louis-Georges Tin. With essays on topics like the Inquisition and Pat Buchanan, it’s a well-done and important book, but I found it too depressing for anything more than fipping through.

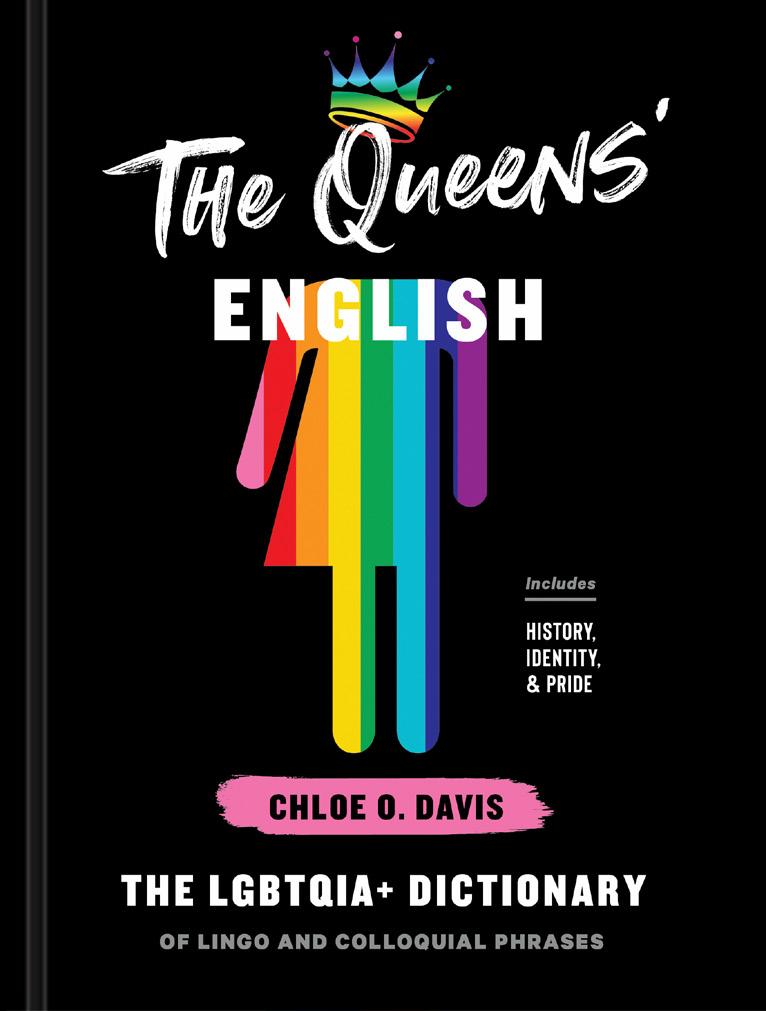

Chloe O. Davis’s new book, however, is a nonjudgmental celebration of the creativity of queer culture. The Queens’ English: The LGBTQIA+ Dictionary of Lingo and Colloquial Phrases gets at how giving a name to an identity, desire or behaviour can make it more real. Something more real can be discussed, and something that can be discussed can be integrated and accepted into a larger dialogue that has, traditionally, been uneasy with all things queer. (Here I’m following Davis’s example in the book, using “queer” as a “catchall for people who identify as anything other than heterosexual and/or cisgender,” though she also uses LGBTQIA+.) Davis has a social mission: to make multifaceted queer communities visible and accessible in a resource that might as easily be used in the classroom as chatted about on bar stools.

But innovative use of language is also just plain fun, even more so if you know the history. If you’ve ever overheard clueless straight teenagers in the mall “throwing shade,” as they imitate dialogue from RuPaul’s Drag Race, then you can smile to yourself knowing that “shade” was coined back in the 1980s by New York City Black and Latino queens in the ballroom scene. Ballroom culture, with its arch drag competitions, has not only provided RuPaul with many of the catchphrases that his empire has popularized (think: “reading,” “category is…” and “sissy that walk”), but provides the foundation for many key terms in Davis’s lexicon. “It’s important to document because that’s how we share our history with generations to come,” Davis tells me in a phone interview. “If you don’t document, then you become lost, and sometimes create erasure in a community that’s been marginalized.” Davis, a dancer and all-around creative type, got the idea for the book back in 2006 when she was with the Philadelphia Dance Company. Some of her fellow dancers were part of the ballroom scene and they’d throw around jokes that sounded coded to Davis – she’s a millennial who identifes as a Black bisexual woman. She started collecting those words and others, then began interviewing people, gathering expressions from all corners of the queer universe. Going through the dictionary, I notice certain categories of queer vocabularies. Many words come from slang, emerging when subcultural groups create an insider’s language, often with humour and a heap of bitchy attitude. There’s “full house” for someone with a sexually transmitted disease, or “butchkini” for a bathing suit a butch lesbian or masculine queer person might wear. I was familiar (well, not personally) with “lesbian bed death,” but got a chuckle discovering that “fve-year tune-up” meant the “rare urge of a lesbian woman to have a sexual experience with a man.” “Spaghetti” is “someone who identifes as straight until they get intimate with a queer person or person of the same gender,” that is, straight when dry, but not after a few drinks. “Have a seat,” which Davis traces to the Black gay community and the larger queer and trans people of colour community, is defned as “a phrase expressing dissatisfaction with a person or action.” It conjures the simple image of an authority fgure about to give a lecture, but the superlative phrase is, perversely, “have several seats.” Then there are words imported from the health and political sectors, like the pseudo-medical “conversion therapy,” “endo” for an endocrinologist that a trans person might visit, and “MSM” and “WSW,” respectively “men who have sex with men” and “women who have sex with women.” Healthcare types like “MSM” and “WSW” because it disconnects self-identity from behaviour since disease generally doesn’t care how you identify. The leather and kink community also overfows with neologists: “aftercare” for the “time and compassionate attention given to a partner after sex, scenario role-play, or BDSM activities,” as well as “daddy dom,” who might be looking for a submission “boy.” Other words seem to originate from a conscientious craving for people trying to make themselves visible by creating a label that anyone – whether their grandmother or a mainstream news source – would feel comfortable using. There’s “demisexual” (one of Davis’s personal favourites) for someone who experiences “sexual attraction only when a strong emotional connection is present.” A “graysexual” is a “sex-positive asexual person who is not sexually averse but may not have sexual feeling or attraction toward others.” You can also call a graysexual a “grace” or “gray ace,” and so deduce that “grace” is a fuzzifcation of “ace,” which is short for asexual.

Needless to say, there are many, many words for people’s junk and what’s done with it: backdoor, bussy, schnauzer, jewels, package, PIV, bumper-to-bumper, pegging and “kai kai,” the act of sex between two drag queens. As well as identifying the community of origin for many words, Davis includes explainers on HIV/AIDS; coming out; the hanky code (e.g., gray left is bondage top); pronouns; and the differences between gender identity, gender expression and sexual orientation. When I ask her if there were words she considered including but left out, Davis didn’t give me an example, but told me the draft went through “so many” sensitivity readings. She’s still keeping a list of words she fnds, and has been researching Polari (a gay British “secret code” language that may have roots back as far as the 16th century) for a forthcoming UK edition.

One of my recent language peeves is “BIPOC” for “Black, Indigenous and People of Colour” – not for the acronym’s meaning, which is useful, but because, for me, words that start with “bi” always nudge my associations straight to bisexuality. (You can’t imagine where “homogenized milk” takes me.) I run this by Davis, but she doesn’t agree. She points out that the “BI” in “BIPOC” has a capital “i,” which differentiates it. Yet she has other issues with the surge in the use of “BIPOC.” “There is beauty of intersectionality, and saying ‘people of colour,’ yes. But I think it’s more important that if we’re talking about a specifc group, then we talk about them. If we’re talking about Black people, we say ‘Black people.’ If we’re talking about Asian-American Pacifc Islanders, then we say that, we don’t say POC,” says Davis. “A lot of times it’s non-Black people or non-people of colour who are using ‘BIPOC.’ Maybe it makes them feel they’re being politically correct about things. But it’s important to acknowledge and focus on the community we’re actually talking about.” And that’s the beauty of language well used and a book like The Queens’ English. Social tensions often come from vague, unexamined feelings and stereotyped generalizations. The more specifc we can be, the better we understand each other. And the better our mutual understanding, the more direct the route to meaningful solutions. So stop clutching your pearls, Judy. Please and thank you. Now sashay away. Bye, bye, Felicia.