6 minute read

At Home with Artists: The Education of Ted Degener

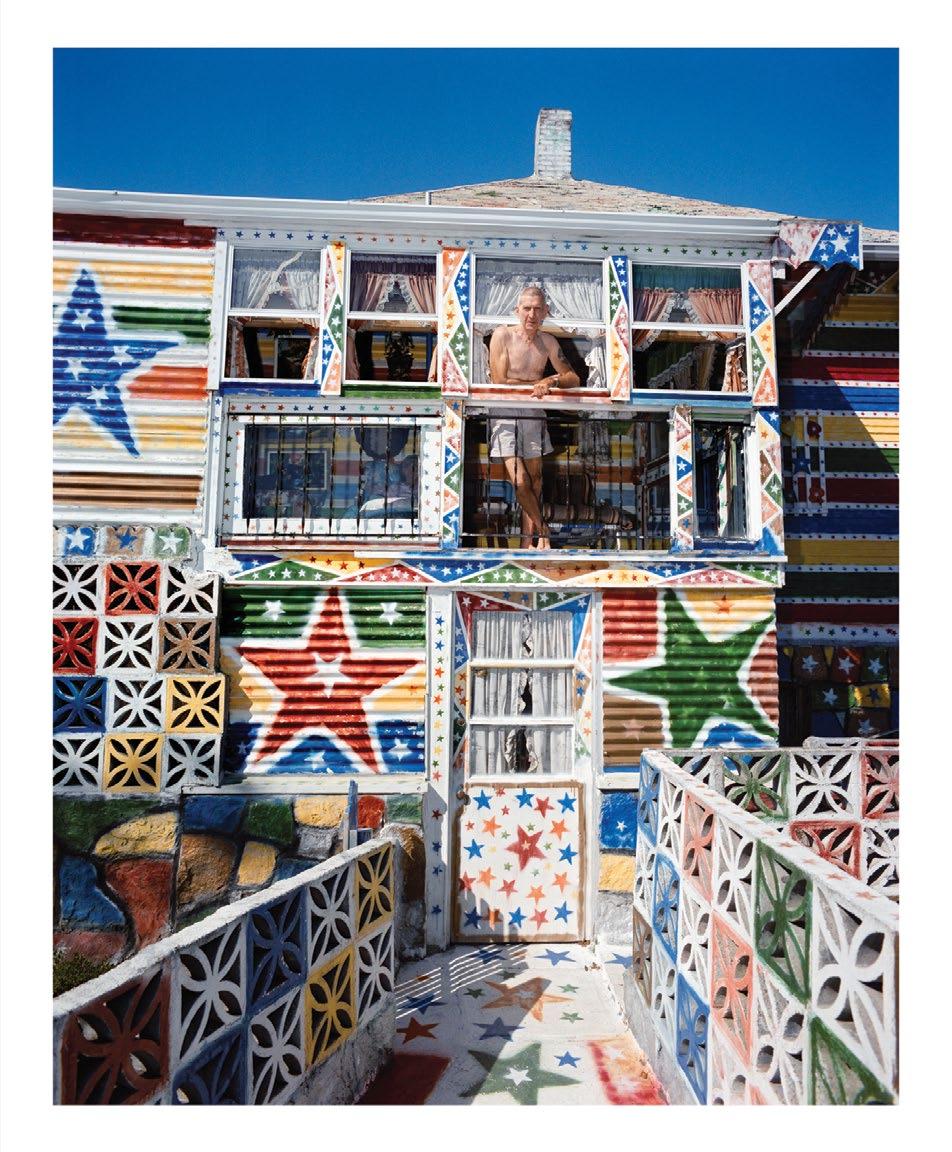

Ace Parson in the window of his Rainbow House in Vancouver, Wash., in 1995 by Ted Degener. Photo courtesy Ted Degener

At Home with Artists: The Education of Ted Degener

By Annalise Flynn

In January 2023, Intuit will present an exhibition of photography and film by Ted Degener, an artist who has spent countless hours traveling the United States to seek out creators of artist-built environments— personal spaces like homes, gardens and studios fully transformed into continually evolving, site-specific and life-encompassing works of art. Given the expansive, transformative and rooted qualities of artist-built environments and that they are typically intended to be experienced as a single work rather than a collection of disparate objects, they are particularly difficult to share inside institutional walls. Oftentimes, pure documentation of sites fails to capture even a small fraction of the magic of experiencing the place in three dimensions—of finding your body enveloped by the creative work of another.

Mary Proctor’s Art Yard in Tallahassee, Fla., in 1997 by Ted Degener. Photo courtesy Ted Degener

Degener’s photos, however, don’t attempt to merely document an artwork or transport a viewer to a place. These portraits capture the artist in their space, inhabiting their work— something many have done for a lifetime, growing with and within their work. They capture the joy of making and the pride of sharing it with the world. They reveal the one thing that many environments are incomplete without—the dynamic presence of their makers—something that can never be experienced or recreated once the artist has left the site or passed away. Degener’s collection of portraits comes together to reveal something like the lives of these artists themselves—a lifelong pursuit, an impassioned collecting and the making of something enormous that will never be quite complete. In this interview, I spoke with Degener to learn more about his practice.

Annalise Flynn: How did you first become interested in artist-built environments and road tripping?

Ted Degener: Right after college, I did construction in Woodstock, N.Y., and happened to visit Clarence Schmidt’s famous site, which was already in ruins. That was a big influence. I would go to New York and often visit the Strand Bookstore. I bought a book called Fantastic Architecture, Roger Cardinal’s book [Outsider Art], and Seymour Rosen’s book In Celebration of Ourselves; curiously, all on the discount racks. I became more and more interested in them. There was also a book called Amazing America, which made a huge impression on me. It included a guide to sometimes environments and sometimes quirky Americana. I became interested in both types of places at the same time, as well as festivals and religious sites in the United States— sort of as a way to understand our odd and beautiful country.

I became interested in the organizations SPACES, Kansas Grassroot Arts Association and The Orange Show. These associations would do a map every month. When the thing came out, I would be really psyched to see it…and I would often go on road trips to follow those maps. In the early days, there wasn’t much information about any of this stuff… Following the maps helped me find a bunch of places, and sometimes I also just wandered the back roads. That was the greatest thing, when you just went around a corner and found something that blew your mind.

AF: Why the focus on portraits versus photos of the environments alone?

TD: I do portraits because they capture an important moment in time. The work of environments has more power when the artist is alive, but I do believe in preservation of these sites. It’s a challenge to find a moment that tells the story or at least part of the story of a site or a person.

AF: What kind of relationship do you have with the artists? How have artists responded to your work?

TD: Some artists I’ve visited many times, some just once. I find that people are very happy to share their work as it is their passion. There are photographs I’ve never shared because the people were so fragile. Of course, everyone is different, and most people are more interested in what they’re doing than what I’m doing. I’m very open about what I tell the artist about their work, and I think they appreciate my enthusiasm. In a way, most environments are made as unfinanced public art, in my opinion, waiting for an appreciative audience.

AF: Why do you take these photos? Is it primarily to share them with other people, to increase recognition of the artists, something you just do for yourself?

TD: I suppose, in some cases, I try to promote the artist’s work, and in some artist’s cases, I try to protect them. I think of myself as someone who just makes a historical record on people who might not be appreciated otherwise.

AF: How do you find out about environments?

TD : Now, through Facebook, dealers at the Outsider Art Fair. In the old days, it was much more difficult, but through the organizations I mentioned. By luck, I just happened onto Margaret’s Grocery. I missed Mary T. Smith because KGAA [Kansas Grassroots Art Association] gave the wrong town, and I spent three days asking for directions there.

AF: What about this work (artist-built environments) is important to you? What about your work is important to you?

TD: It [artist-built environments] tends to be made by self-educated people who are working things out as they go along. Be it the quality of their brushstrokes or their architectural ideas, they must really believe in what they’re doing to engage in a life’s work. I’ve always found self-educated people interesting. I think the real geniuses like Lonnie Holley even invent their own language. The best things about America are its individualism and diversity, and environment builders are sort of heroes on quest. It’s my quest to appreciate their contributions, and I am perhaps self-educated by them… It’s an art of generosity.

AF: Do you have any favorite memories of a particular trip or artist?

TD: Going around the corner and seeing Margaret’s Grocery, spending time with Leonard Knight, taking the comedy tour of Paul Hefti’s yard at sunset, Finster talking for four hours straight, Jimmie Sudduth playing harmonica like a train with his dogs howling along.

AF: What have decades of this pursuit taught you?

TD: A more democratic and open-minded appreciation of all art. High art—great. Vernacular art—great. As Seymour Rosen said: it’s a celebration of ourselves.

Louis Lee in his Rock Garden in Phoenix, Ariz., in 1995 by Ted Degener. Photo courtesy Ted Degener

This interview with Ted Degener was performed by Annalise Flynn on September 12, 2022. It has been edited for length and clarity.