A Cure for Diabetes

A major breakthrough in cryopreservation brings us one step closer to a cure.

Inventing

TOMORROW

Fall 2022 • cse.umn.edu

ADMINISTRATION

Dean Andrew Alleyne

Associate Dean, Academic Affairs Ellen Longmire

Associate Dean, Research Joseph Konstan

Associate Dean, Undergraduate Programs Paul Strykowski

EDITORIAL STAFF

Communications and Marketing Director

Rhonda Zurn

Managing Editor

Pauline Oo

Assistant Editor

Olivia Hultgren

Designer Sara Specht

I nventing Tomorrow is published by the College of Science and Engineering at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities for our alumni and friends.

Send letters to the editor: 105 Walter Library 117 Pleasant Street SE Minneapolis, MN 55455

This publication is available in alternative formats upon request. Call 612-624-8257.

NEED A PAST ISSUE? Find it in our online archives at z.umn.edu/inventingtomorrowarchive

ADDRESS CHANGE? Email: csemagazine@umn.edu Call: 612-624-8257

© 2022 Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved.

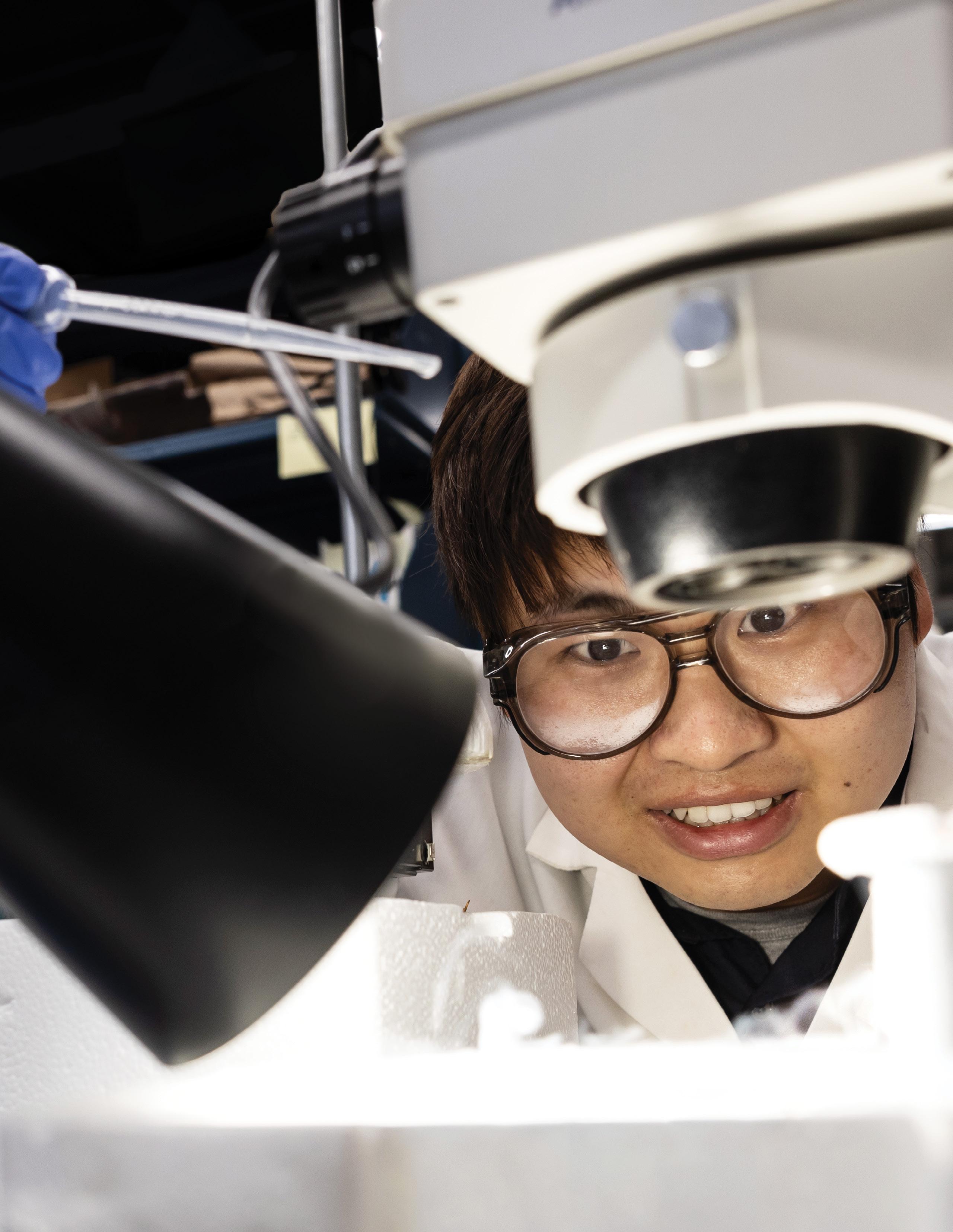

On the cover

University of Minnesota Twin Cities College of Science and Engineering postdoctoral fellow Zongqi Guo is part of a team that has developed a new process for successfully storing specialized pancreatic islet cells at very low temperatures and rewarming them, enabling the potential for on-demand islet transplantation for diabetes patients.

Nearly 250 employers and 2,900 students attended the CSE Career Fair in person this fall. Plus, over 300 students interviewed at Huntington Bank Stadium for jobs, co-ops, and internships in the two days after the event.

Uniquely positioned for the future

Our college has a proud history of rising to meet the world’s challenges. From the development of the first supercomputer to the heart pacemaker to the retractable seat belt, our faculty and alumni have impacted our world in many ways. Today, in a rapidly changing environment, we are once again prepared to respond to the call.

With engineering, physical sciences, computer science, and mathematics all in one college, we are uniquely positioned for innovation through interdisciplinary research and industry partnerships.

The University of Minnesota has generated 200+ startup companies since 2006. We are 18th in the world for patents awarded, including numerous science and technology advancements. Our University brought in $1.15 billion last year in external research dollars fueling discoveries in medicine, robotics, energy, quantum computing, and more.

This issue of Inventing Tomorrow highlights faculty researching self-driving vehicles and a medical sensing patch as part of a new seed grant initiative, alumni who are leading next-generation manufacturing and sustainability, and students who are tapping multiple STEM disciplines to better solve big problems.

We are ready for the future, and we need your help more than ever. With support from our alumni, donors, and industry and academic partners, we can ensure that the people of CSE are empowered to make a meaningful impact locally, nationally, and globally.

Dean, College of Science and Engineering University of Minnesota

Tech DIGEST

Read full stories: z.umn.edu/ techdigest

$22M TO FIGHT CLIMATE CHANGE

UMN leads two new DOE centers

Renewable energy and carbon dioxide storage are two issues at the heart of the world’s climate crisis—and scientists and engineers in CSE are at the forefront of both. This year, the University received $22 million from the Department of Energy to fund two new Energy Frontier Research Centers that will develop promising technologies in mineral carbon storage and sustainable energy catalysis. The UMN is one of only six institutions nationwide to be awarded two of these in one year as part of the U.S. government’s goal to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

A NEW TECHNIQUE TO RELIEVE CHRONIC PAIN

Study finds that sound plus electrical stimulation could treat chronic pain

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one in every five Americans suffers from chronic pain, and doctors have struggled for years to find non-invasive ways to help their patients manage it. Researchers in CSE’s Department of Biomedical Engineering, led by professor Hubert Lim, have discovered a new way to curb chronic pain for people with sensory and neurological disorders. Their method combines two simple things—electrical stimulation and sound. The researchers found the combination of the two activated neurons in the brain’s somatosensory cortex, which is responsible for touch and pain sensations in the body. Lim and his team are planning clinical trials of the treatment in the near future, and hope that this technique will provide a safer, more accessible alternative for managing chronic pain.

ONE AND DONE

$3.7M funds lab-created pediatric heart vessels

One of the greatest challenges in engineering artificial blood vessels for children with heart defects is creating a device that will grow with its owner. With a grant from the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), a UMN team led by biomedical engineering professor Robert Tranquillo is on its way to solving this problem. The researchers’ implantable heart vessels that grow with the recipient will undergo clinical trials that could begin as soon as next year. If successful, these new devices would prevent the need for repeated surgeries in children with congenital heart defects. The funding is part of the DOD’s Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs, which fund projects that are “transforming healthcare through innovative and impactful research.”

A BIG HEAD AND TINY LITTLE ARMS

New dino reveals why T. Rex had small arms

Let’s face it—we’ve all wondered why history’s quintessential apex predator had such minuscule arms compared to the rest of its body. Now, a team co-led by professor and resident “dino expert” Peter Makovicky has discovered a new huge, meat-eating therapod that may hold the answer. Measuring around 36 feet from snout to tail tip and weighing approximately 9,000 pounds, Meraxes gigas had a similar body plan to the T. Rex. With this new specimen unearthed, the researchers found that large, mega-predatory dinosaurs in all three families of therapods evolved in similar ways. As their skulls grew, their arms shortened. Although there is still much debate in dino academia as to why this happened, Makovicky suggests that the arms may not have been important at all, and the skull was actually being optimized to handle larger prey.

BUILDING SOFT ROBOTS THAT GROW LIKE PLANTS

Engineers discover nature-inspired process for synthetic material growth

Plants grow so efficiently that they’re sometimes able to crack the strongest concrete or weave through mazes underground without missing a beat. CSE researchers led by professor Chris Ellison, the Zsolt Rumy Innovation Chair in the UMN Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, took this idea and translated it to an engineering system— soft, pliable robots that grow as they move. Current soft growing robots drag solid material behind them, which makes navigating complex paths difficult.

Ellison’s interdisciplinary team used a process called photopolymerization. This harnesses light to transform liquid monomers into a solid material, similar to how plants use water to transport building blocks that harden into roots. Because the UMN researchers’ robot grows by turning liquid into solid, it can better navigate hard-to-reach places like underground pipes or even inside the human body.

NEW VACCINE WINS BY

A NOSE

Method of nasal delivery could lead to better HIV and COVID-19

vaccines

For the past two years, the phrase “shots in arms” has been all over news headlines. But what if we didn’t need to get a needle in the deltoid to protect ourselves from the COVID-19 virus? CSE assistant professor Brittany Hartwell is part of a team that has developed a new way to effectively deliver vaccines through mucosal tissues in the nose. While nasal vaccines have historically proved difficult to make, the researchers’ method generated even stronger immune responses in mice and primates than those seen with injected vaccines, paving the way for further development of these vaccines.

INTRODUCING THE FIRST 3D-PRINTED, FLEXIBLE OLED Research aims for lower-cost digital displays

In a groundbreaking new study, University of Minnesota mechanical engineers used a customized printer to, for the first time, fully 3D print a flexible organic light-emitting diode (OLED) display. The discovery could allow for lowercost electronic displays in the future that could be widely produced using 3D printers by anyone at home, instead of by technicians in expensive microfabrication facilities.

MAKING MIND READING POSSIBLE

Researchers build bionic arm controlled by brain signals

For years, science fiction writers have dreamed up futures where humans have chips implanted in our brains that can read our thoughts. For CSE researchers, this future isn’t too far off—and it’s less invasive than that. A team of biomedical engineers, with the help of industry collaborators, has developed a device that attaches to the peripheral nerve in a person’s arm. When combined with an artificial

intelligence computer and a robotic arm, the device can read and interpret brain signals, allowing upper limb amputees to control the arm using only their thoughts. This technology circumvents the issues of traditional prosthetic arms, which can be cumbersome, unintuitive, and take months of practice for amputees to learn how to move them.

BUS-SIZED DETECTOR AIMS TO CAPTURE SUBATOMIC PARTICLE

UMN part of collaboration to shed light on the Universe’s origin story

Scientists believe that a better understanding of neutrinos, one of the most abundant and difficult-to-study particles, may lead to a clearer picture of the origins of matter and the inner workings of the Universe. Physics and astronomy assistant professor Andrew Furmanski is part of an international team that has nearly ruled out a major theory about neutrinos using the MicroBooNE, a giant particle detector. The international experiment has close to 200 collaborators from 36 institutions in five countries and uses cuttingedge technology to record spectacularly precise 3D images of neutrino events. With this new data, the researchers are one step closer to learning more about how the Universe was created.

Graph-based methods in machine learning

New dream teams IN SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING

Zhi-Ling Zhang

The InterS&Ections seed grant program has sparked two interdisciplinary projects that are likely to make a lasting impact. Story

A unique advantage of the College of Science and Engineering is how it brings together engineering, math, computer science, and physical sciences in one location. As a result, researchers from across departments have teamed up to solve problems in quantum computing, environmental engineering, and many other complex fields. But in a place with such wide-ranging expertise, there’s also a lot of untapped potential.

Launched this past year, the “InterS&Ections” seed grant program offers incentive for scientists and engineers to work together in creative new ways. “Our goal is to seed entirely new collaborations

within the college, where the science departments and the engineering departments are both first-class partners,” said Joseph Konstan, associate dean for research.

The program kicked off with a Zoom “collision” webinar last winter.

During the webinar, faculty attended breakout sessions, made connections, and brainstormed ideas. To qualify for the grant, their proposals needed to cross between science (including math) and engineering, and bring together a new team to address a significant challenge. Additionally, the projects had to show promise for making a big impact and attracting substantial funding down the road.

In total, 23 teams submitted pre-proposals, with two teams winning an award for 2022-23. Each will receive around $100,000 over one year, which will support research assistants, materials, and equipment, with potential renewal for a second year based on progress.

“This isn’t a set of scientists saying, ‘I need engineers to build something for me,’ or a set of engineers saying, ‘I need a mathematician to create this formula for me,’” said Konstan. “With these teams, there is genuine intellectual synergy and each disci pline will be advanced by a signifi cant project.”

There’s been a lot of progress toward self-driving cars in recent years, but we still have a long way to go before the system runs like a well-oiled machine. Even with all the advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning, autonomous vehicles (AVs) are still not well-equipped to handle accidents, bad weather, poor visibility, and other unexpected situations on the road.

These challenges have given rise to the concept of teleoperated AVs, or AVs that are partially controlled by a remote operator when necessary. While this concept makes AV adoption more feasible, there’s more to it than just a person managing the vehicle from an off-site location.

“You need the vehicle to receive directions, but you also need the system that is operating everything to quickly receive data from the vehicle and from other vehicles, to give that remote operator a sense of what’s going on,” said Konstan.

It’s a complicated problem, but the researchers working on this InterS&Ections project are determined to figure it out. “We don’t just want to make the car smart—we also want to make the infrastructure smart by using advanced network communication technologies such as 5G and

edge computing,” said Zhi-Ling Zhang, lead PI and a professor in computer science and engineering.

Think of it as air traffic control, but for self-driving vehicles. Zhang’s team will develop new models and algorithms to move us closer to edge-assisted intelligent driving systems. Unlike the larger-scale cloud computing, edge computing puts the data closer to the location where it’s being generated, at the “edge” of the network.

Find out more Learn about the genesis of the University of Minnesota MnCAV Ecosystem in CSE News: z.umn.edu/MnCAVresearch

“The amount of data we need to collect is huge, and shifting all that information to the cloud would take a lot of bandwidth and result in delays,” said Zhang. “Edge computing will help us process the information faster.”

Project 1: Paving the way for smarter and safer AVs

Zhang has led some of the world’s first large-scale, commercial 5G measurement studies. Co-investigator Rajesh Rajamani is a leading expert on estimation and vehicle control for intelligent transportation systems. And co-investigator Jeff Calder is an expert on graph learning and related topics. Putting their heads together, the team is likely to lay a foundation for future funding, while boosting Minnesota’s reputation as a leader in AV research.

Thanks to its state-of-the-art research facilities, the University is an ideal place for this project. Under the umbrella of the new “MnCAV Ecosystem,” researchers, government, and industry partners are coming together to develop and test connected and autonomous vehicle technologies. Led by the Center for Transportation Studies, this ecosystem includes a fully automated 2021 Chrysler Pacifica minivan that serves as a customizable, experimental testbed.

Ultimately, the project team will help identify the most critical needs for the nation’s physical and digital AV infrastructures. “We’re not funding this because, at the end of a year or two, we’re going to magically see these autonomous vehicles driving around campus,” said Konstan. “It’s about a longer-term national priority—and this team is addressing the gaps that need to be filled in order to get us there.”

2022-23 InterS&Ections seed grant team

Project 2: Improving emergency medicine through wearable patches

If you’ve had the misfortune of visiting an emergency room, you’re probably familiar with the waiting game. In many cases, you start by waiting in the lobby for an exam room. Once a room opens, you wait to see a nurse, who will likely take some lab samples. Next, you wait to see the doctor. Meanwhile, the doctor waits for your lab results. It’s likely that hours go by before you find out

what’s wrong and what to do about it, and by that time, your vitals may have changed.

Imagine if all this waiting time could be used to gather valuable information through an easy-to-use, wearable patch. That’s the vision behind this InterS&Ections project. Researchers from electrical and computer

engineering, chemistry, mechanical engineering, civil engineering, and medical device design are joining forces to create a working prototype.

“The idea is to develop a low-cost patch that works as an electronic sensing device, that could be easily applied to the skin without help from medical professionals,” explained Sarah Swisher, the lead PI on the project and assistant professor in electrical and computer engineering. “The device would provide information about specific biomarkers to help medical providers make decisions about how to triage patients, and how to treat each patient most effectively. This could be a gamechanger for pre-hospital care.”

relevant for analyzing a patient’s status, related to stress, metabolism, the oxygenation of blood and tissues. If we can detect potassium in this miniaturized sensor over a long period of time, we’re confident that we can expand it to analyze ions for other molecules.”

Other than continuous glucose monitors, commercial wearables for interstitial fluid analysis are few and far between. Swisher dreams of the day when patients can walk into the ER, stick on a patch, and voila, numerous biomarkers are transmitted to the nursing station in real-time. Along with greatly improving emergency care, the patch could reduce health inequities in medically underserved populations, where many hospitals are short staffed and access to low-cost diagnostic tools is limited.

In addition to civilian use, an easy-to-apply sensor patch that records and transmits data could be extremely beneficial in military applications when soldiers are injured on the battlefield far from medical facilities.

Swisher has expertise in designing and fabricating flexible electronics and biosensors. Her co-investigators have combined expertise in ion-selective electrodes, electrochemical sensors, medical device design, and emergency medicine. Working together, they have the knowledge needed to develop a successful prototype for future clinical trials.

“We’re excited,” Swisher said. “The college’s new InterS&Ections seed grant program gives faculty the chance to pull people together with complementary strengths and come up with a vision on how we could make a global impact.”

Using transdermal microneedles that probe the fluid just underneath the skin, the patch would be far less invasive than existing blood sampling methods. Moreover, it could track biological markers over a period of time, such as during the ambulance ride to the hospital. “So when you arrive, the doctors don’t just get a single snapshot in time, but actually have information about how your biomarkers have changed over the last 10, 15, or 30 minutes,” said Swisher.

Initially, Swisher’s team will focus on potassiumion analysis, which is essential to monitoring heart conditions. From there, the sky’s the limit. “There are lots of biomarkers in that interstitial fluid that are

Andreas Stein Co-PI Distinguished McKnight University Professor Chemistry

Nanomaterials synthesis

Bühlmann

Sandra Henry’s Quest to Make Buildings More Environmentally Friendly

BY KERMIT PATTISONDuring a stint as Chicago’s chief sustainability officer, Sandra Henry wrote the ordinance the city adopted to become the largest metropolis in the United States to commit to 100 percent clean energy.

That’s just one career highlight of this Minnesotatrained engineer—and Master Gardener—whose life has been intertwined with the emergence of the sustainability movement.

Henry was an accounting major on the University of Minnesota Twin Cities campus when a professor took her aside, complimented her talents in math, and suggested she take calculus. She followed his advice. With more encouragement from the same mentor, Henry soon discovered that she also loved physics.

“The concepts and ideas were really interesting to me,” she recalled. “Being able to explain your physical world through math and science was really fun. I decided to change my major to mechanical engineering.”

By her senior year in 1991, Henry had gained enough engineering experience to secure a job at Northern States Power (now Xcel Energy) where she developed Saver’s Switch. The program has since helped millions of residential users conserve energy by remotely switching consumer loads on and off. She wrote software, designed the control protocols, and made decisions about equipment, installation, and operations.

“I realized that the most cost-effective unit of energy is the one we don’t produce,” she said. “That was the beginning of realizing that I could spend a career doing this kind of work and really have fun at it.” As it turned out, a new branch of engineering was taking root. “We didn’t call it ‘sustainability’ at that time,” she said with a chuckle. “It was ‘direct load control’—not a very sexy name.”

Henry spent nearly two decades as a manager and consultant for utilities in Minnesota and Illinois, including the Chicago-area utility ComEd. Most programs it now offers, she had a hand in either creating or running.

In 2015, Henry shifted into the nonprofit sphere in order to pursue deeper systemic changes. One obvious target is buildings, which are responsible for nearly half of global carbon dioxide emissions.

“Once you build a building, it’s there for 40 or 50 years,” she explained. “If you want to make an impact on its carbon footprint, it’s better to have that conversation before you build it. That’s the conversation I wanted to be in.”

From 2018 to 2019, Henry served as the chief sustainability officer for the city of Chicago. During her tenure, she drafted a resolution to transition all cityowned buildings to 100 percent renewable energy by 2035 and to convert all Chicago Transit Authority buses to electric energy by 2040. The Chicago City Council unanimously approved the measure and subsequently adopted a series of additional conservation measures.

Since then, several Chicago-area organizations devoted to making buildings greener have benefited from her expertise. In 2022, she became the president of Slipstream. The nonprofit, with employees across the United States, develops clean energy solutions that can be deployed at large scale while ensuring equitable access.

“We cannot have a clean energy transition and resilient future unless everybody is on board, from the folks who can afford it to the ones who cannot,” Henry said. “We have to be inclusive in our discussions.”

When not working to reduce carbon footprints, Henry enjoys leaving her own footprints in the soil. During her years in Minneapolis, she discovered a love of gardening and earned a Master Gardener certificate from the University of Minnesota. Her hobby has provided a window on climate change: she has witnessed the growing seasons getting longer and rising temperatures affecting what plants can thrive in northern climates.

“We are almost at the point now when we cannot stop this climate change train,” Henry reflected. “But we can be more resilient and we can be more mindful. A lot of it comes back to reconnecting people to the earth—and gardening is a great way to do that.”

Building Greener FROM THE GROUND UP

Sandra Henry ME ’91 (pictured on Chicago City Hall’s Green Roof) helped engineer a greener future for the city as its chief sustainability officer. As a resident and master gardener, she tends two plots: one that grows plants for a food pantry; another— lush with greens, herbs, pole beans, tomatoes, and squash—for family meals.

A cure for diabetes?

A major breakthrough in cryopreservation brings us one step closer to a cure

Diabetes is the seventh leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for nearly 90,000 deaths each year according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While there are ways to manage the disease, a cure has remained elusive for many years. Now, researchers at the University of Minnesota and the Mayo Clinic have taken a major step forward in finding that cure. Pancreatic islet cell transplantation—a process where groups of cells transferred by doctors from a healthy pancreas begin to make and release insulin on their own in the recipient—is one method being explored to cure diabetes.

Researchers were able to store tiny droplets encapsulated with pancreatic islet cells at very low temperatures for up to nine months and then use novel rewarming techniques before transplantation. Shown is one approach studied by the team, which uses lasers to rapidly rewarm cryopreserved droplets of islets.

Photo credit: Zhan, L., Rao, J.S., Sethia, N. et al.

Through pooling cryopreserved islets prior to transplant from multiple pancreases, the method will not only cure more patients, but also make better use of the precious gift of donor pancreases.

—John Bischof

The UMN-led team has developed a new method of islet cryopreservation that solves the storage problem by enabling quality-controlled, long-term preservation of the islet cells that can be pooled and used for ondemand transplant. Their method demonstrated high cell survival rates and functionality in mouse, pig, and human islet cells and has the ability to be scaled up to reach large numbers of people worldwide who suffer from this progressively debilitating disease.

John Bischof, the Carl and Janet Kuhrmeyer Chair in Mechanical Engineering, and Erik Finger, associate professor of surgery in the medical school, headed up the study.

Professor John Bischof and his team have developed unique processes to cryopreserve and rewarm cells, tissues, and even entire organs.

However, it’s been difficult to get a sufficient amount of islet cells, which have to be pulled from multiple donors, because they can not be safely stored for long periods of time.

This research is part of a larger effort involving cryopreservation methods led by the University of Minnesota. In 2020, the University of Minnesota and Massachusetts General Hospital were awarded $26 million over five years from the National Science Foundation to create the Engineering Research

Center (ERC) for Advanced Technologies for the Preservation of Biological Systems (ATP-Bio). ATP-Bio aims to achieve major bioengineering breakthroughs by developing and deploying technology to “biopreserve” or “cryopreserve” numerous biological systems from cells to full organisms.

“Photo by Rebecca Slater

Adel Elmahdy has long been interested in building things. As a child growing up in Japan, it was Legos, miniature cars, robots— anything his parents put in front of him. Elmahdy turned his passion for piecing things together into a B.S. in electrical and electronics engineering and an M.S. in wireless communication in Egypt before landing in Minnesota.

Here, he’s pursuing a Ph.D. in electrical engineering and two more master’s degrees, one in mathematics and another in computer science.

“In order to solve a significant problem, you cannot limit yourself to a specific discipline,” Elmahdy said. “Having this variety of backgrounds has really shaped me into a better theoretical computer scientist who can handle a broader set of challenging problems in machine learning.”

Elmahdy’s research at the University of Minnesota focuses on using mathematics to understand the intricacies behind machine learning algorithms. His work has many applications, which include refining online product recommendation systems and improving rankings algorithms on apps like Amazon.

He was drawn to the University of Minnesota by his advisor, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Associate Professor Soheil Mohajer, whose research lies at the intersection of math, engineering, and computer science.

Intersections are somewhat of a specialty for the College of Science and Engineering. CSE is the

only college at a major research university in the United States that brings the engineering, computer science, mathematics, and physical science departments together into one college.

all their hard work! That was the clicking point where I realized I wanted to go into STEM.”

“Now, Hamilton’s focus isn’t so much destroying machines as it is exploring the materials that go into making them. She’s majoring in materials science and engineering with a minor in astrophysics. One of her future goals is to work with materials that are used in space.

—Adel Elmahdy, CSE doctoral and master’s student

This interdisciplinary, collaborative atmosphere impacts the faculty— who can more easily partner with colleagues from the standpoint of sharing resources—as well as benefits the students. Undergraduates and graduate students at the college get to tap into a deep, unique well of options for learning and future careers.

For CSE senior Ashlie Hamilton, it wasn’t the excitement of building things that drew her to science and engineering. It was actually the destruction of things—“things” being the robots that were a part of her older brother’s National Robotics League team, a club at her former high school in St. Paul, Minn., where students build robots to face off against each other in combat.

“It was really my brother and watching his robots that got me into science,” explained Hamilton. “I thought it was so cool watching them destroy each other and ruin

Hamilton works in Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science Professor Nathan Mara’s lab, picking apart the nuances and mechanical properties of titanium nitride, a metal ceramic composite material.

“I’m doing the fundamental research in order to maximize the properties that this material can have,” Hamilton said. “From there, engineers can take that and apply it when they’re building semiconductors, electronics, and aerospace vehicles.”

Computational skills are something that CSE senior Annie Bonde is very familiar with. Bonde came to the U as a freshman studying biomedical engineering because she was interested in medicine. She added computer science as a second major after taking her first programming class.

“I quickly realized that there’s a big gap between engineers and computer scientists,” said Bonde, who received the CSE Alumni Scholarship and Maxmillian Lando Scholarship. “I felt like it would be really cool for me to merge those two fields together. I think combining science and engineering

In order to solve a significant problem, you cannot limit yourself to a specific discipline.

CURRENT PROGRAMS

CHILDHOOD PASSION

is more important than people realize, because you can’t build off of scientific principles that you don’t fully understand. If you’re trying to design a device that performs a certain function and you can’t figure out the best way to optimize the software behind it, it’s not going to reach its full potential.”

During her first year at the U, Bonde worked as a research assistant in the College of Biological Sciences on synthetic cell development with faculty members Kate Adamala and Aaron Engelhart. There, she was able to put her CSE expertise to good use and introduced computational biology to the lab by developing a computer program for culling bacteria.

It was that research experience that inspired Bonde to apply for the Summer Undergraduate Fellowship in Sensor Technologies at the University of Pennsylvania after her junior year. She spent the summer working on magnetometer sensors that could allow the brain to send signals to external devices, such as a prosthetic limb.

“I think my experiences [in Minnesota] have really shown me the importance of having a diverse

background,” she said. “I get to learn mechanics, and I get to learn chemical engineering and electrical engineering. I get to learn a little bit of everything, and I think that makes for a really strong engineer when you’re able to use knowledge from different fields.”

learn some of their skills that you wouldn’t necessarily get in a typical engineering curriculum.”

Preparing students for meaningful, well-paying careers is ultimately the goal of any college, and CSE rivals its competitors with the richness

“

I think combining science and engineering is more important than people realize…

—Annie Bonde, CSE double major

The first was with Microsoft, where he researched the privacy issues behind Natural Language Processing, or the technology that lends itself to text completion on laptops and other devices. The second was with San Francisco startup Amplitude Analytics, where Elmahdy developed a model for digital product analytics like website user data.

Industrial and systems engineering (ISyE) senior Mark Borland agrees, though his favorite part of the major is how it combines science, engineering, and business.

Borland is tackling his undergraduate honors thesis, inspired by what he learned about society’s dependence on the electric grid from Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Professor Paul Imbertson in the interdisciplinary Grand Challenge course “Power Systems Journey.” He plans to take a broader, multifaceted look at this problem and compare how prices are determined in a provider-consumer energy market.

“I definitely think there’s a benefit to taking an engineering approach and looking at business problems,” said Borland, who’s minoring in leadership and management. “If you do the management minor, you also get to see the Carlson [School] curriculum a bit, and you can get a feel for the business side of things and how they learn. It’s cool to

and quality it offers. Hamilton, a first-generation college student and recipient of the Ed & Cora Remus Scholarship, is grateful for many chances to explore.

“At the U, I’ve been able to develop myself academically through research and networking opportunities, while also being able to explore and develop myself through other activities outside of the lab,” said Hamilton, who enjoys practicing karate in her free time and also plays baritone in the University of Minnesota Marching Band. “I really like how versatile my degree is. You can either take a more science route and go into research or academia, or you can take a more engineering route and go directly to industry. It opens up a lot of different opportunities for me.”

The right combination of elements is also a boon to Elmahdy. He credits the breadth of knowledge he’s gained from his three degree programs for making his two internships possible.

“The degree that I’m getting from the University has allowed me to do these internships in different topics that are totally different from what I’m doing in my research,” said Elmahdy, who plans to continue doing research in some capacity after he gets his Ph.D. “Having access to all the courses from the math department and computer science departments through my program here has really enabled me to tackle new problems, even if they’re out of my comfort zone or out of my expertise.”

Bonde plans to leverage her computational and biomedical background to work in industry for a couple years before applying to medical school. But regardless of her future plans, she hopes to keep integrating science and engineering whenever possible.

“It would be really interesting to work in a field like radiology, for example, and then make it more of an engineering role where I could, say, design an AI program to diagnose certain diseases that you can obtain from imaging,” Bonde said. “Moving forward, I know I’m going to have such a solid foundation that no matter what role I end up in after graduation, I’m going to be able to succeed.”

BUILDING ON MINNESOTA’S LEGACY

A student hub for innovation, entrepreneurship, and experiential learning

It was burnt toast that led Minneapolis resident Charles Strite to invent the automatic toaster in 1919. And it was his invention that inspired the name for an inviting basement space in Walter Library where new ideas can pop up.

The Toaster Innovation Hub is 6,500 sq. feet of adaptive workspace designed to foster creativity, innovative thinking, and entrepreneurship. Erik Halaas, innovation outreach and program specialist, oversees it with a dozen student employees. They include Sultan Koroso (CompSci ’26), Ian Alexander (CompE ’24), Lauren Kelly, (BME ’24), and Alex Trousil (ESci ’25). “Apart from having great students, CSE has been involved at various levels,” Halaas said. “From active seats on our steering committee to

student-led efforts by organizations like Society for Women Engineers, and partnerships with the Technol ogy Leadership Institute—to host everything from informal info sessions to summer accelerators— and Anderson Labs to provide hands-on activities and prototyping workshops.”

The Toaster is a joint effort of University of Minnesota Libraries and the Gary S. Holmes Center for Entrepreneurship at the Carlson School of Business that opened February 2020.

“This is a hub where students are encouraged to come together, problem solve, and be inspired to design the next big thing,” said John Stavig, Holmes Center director. “Projects like Telo Design’s innovative approach to the rollator

walker provide a concrete example of this vision in action.”

The startup’s founders, who often met in the Toaster as undergrads, saw their concept go from idea to reality by leveraging University resources—including CSE professor Will Durfee’s “New Product Design and Business Development” course, which brings Carlson and CSE students together to develop a product concept, a working prototype, and an extensive business plan.

Telo Design won the general division of MN Cup in 2022. It’s now a step closer to product launch. Plus, one cofounder is sharing lessons learned each Friday in Halaas’ “Innovation for Public Good” class in, you guessed it, the Toaster!

Manufacturing 4.0

Minnesota-born Rob Bodor draws from diverse disciplines to innovate and spark rapid growth

BY KERMIT PATTISONManufacturing has entered the socalled Fourth Industrial Revolution and Robert “Rob” Bodor is on the front lines.

Bodor serves as the president and CEO of Protolabs, a Minnesotabased company that has become the world’s leading provider of digital manufacturing services such as injection molding, Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machining, 3D printing, and sheet

metal fabrication. The job caps a diverse career for the Minnesotatrained technologist who earned three degrees in three different specialties from the College of Science and Engineering.

“In technology, especially Internet technology and computer science, everything changes so fast you need to be continually learning,” Bodor said. “The multidisciplinary path that I took prepared me very

well for that—because in every new program, I was in some ways starting from scratch and having to learn a new discipline. The main things that education provides are skills for learning how to learn, and the University prepared me well.”

Just as technology evolves at everaccelerating pace, Bodor himself has undergone plenty of evolution. He majored in electrical engineering and received his bachelor’s degree in

1995. He then shifted to mechanical engineering, earning a master’s degree in 1997. After a five-year stint as co-founder of a tech startup, he returned to the University for a Ph.D. in computer science.

“I came to believe this while at the University—that a lot of innovation happens at the boundaries between different disciplines,” Bodor explained. “A lot of creativity happens when you bring people together from different backgrounds to solve shared problems. They have different toolkits and different perspectives, and those tensions create positive growth and innovation.”

Innovation is the name of the game at Protolabs. The company was founded in 1999 by entrepreneur Larry Lukis with an ambitious goal: to revamp the ordering and manufacturing of injection molded parts, thus allowing customers to develop and market products much more quickly. Seeking to digitize the entire manufacturing process, the company created software to communicate designs directly to manufacturing hardware.

The process works like this: a customer uploads a 3D CAD model to the Protolabs website. Within a few hours, the system provides an automated price quotation with design-for-manufacturability analysis obtained by sending the part through a “digital twin” of Protolabs’ entire manufacturing process. Once the customer accepts, the design is translated into digital code, analyzed, and adjusted for optimal production. These instructions are sent to machines on the production floor. At the tail end, pieces go through a finishing process that might include coatings

(to enhance strength or appearance), customization, and polishing. The standard lead time is 15 days, but some orders can be turned around in a single day.

physical, and biological worlds.

When Bodor first saw Protolabs, he recognized something extraordinary. “It was the first time I had seen a company embracing Manufacturing 4.0,” he recalled. “I thought that was revolutionary.”

Protolabs, with nearly $500 million in revenue and 2,800 employees, touts itself as “the fastest and most comprehensive digital manufacturing service in the world.” With 12 global manufacturing facilities (including three in Minnesota) plus an international network of partners, the company makes more than 4,000 molds per month and 4 million individual parts. It serves industries such as medical and healthcare, computer electronics, industrial machinery, aerospace, and automotive.

In 2021, the World Economic Forum’s Global Lighthouse Network recognized Protolabs as an exemplar of the “The Fourth Industrial Revolution.” In the 18th century, the first Industrial Revolution occurred when water and steam-driven engines mechanized production. In the 19th century, the Second Industrial Revolution exploited electricity for mass production. In the 20th century, the Third Industrial Revolution used information technology to transform modern life. Now the so-called “4IR” fuses the digital,

Indeed it was—and an opportunity for Bodor to draw upon his own diverse experience. Besides earning three degrees from CSE, he founded a tech startup (Point Cloud, later sold to ShopNBC), advised Fortune 500 companies (as a consultant with McKinsey & Co.), and worked as a manager in a large manufacturing company (Honeywell).

Since joining Protolabs in 2012, Bodor has left his stamp in several roles. As chief technology officer, he oversaw the expansion of the injection molding business into liquid silicon rubber molding and the addition of CNC turning (in which parts are cut into shape while spinning on an axis, similar to a lathe). He served as the first general manager of the Americas division and his unit more than doubled revenues to $350 million in six years. In 2021, he was promoted to president and CEO.

Even now, far removed from student life, Bodor still can see a clear stamp of his CSE degrees.

“My experience at the University was very comprehensive,” he said. “But I was allowed quite a bit of flexibility and I had a lot of support for pursuing passions and asking questions. That served me really well as I came into the workforce because those were the skills I relied on for much of my career: asking dumb questions and then pursuing answers aggressively.”

“

A lot of creativity happens when you bring people together from different backgrounds.

—Rob Bodor

Homecoming

CSE students, alumni, faculty, and staff came out in droves to join one of the University’s longest-standing and most-attended fall traditions. Jane Lansing (CivE ’76) was honored before the parade

in Minnesota KEEPING RISING LEADERS

A match opportunity for new Faculty Impact Fellowships

Exceptional faculty are embedded in the DNA of the College of Science and Engineering—and when they thrive, so too does our entire University community of students, as well as our state and its economic engine.

Dean Andrew Alleyne has launched the CSE Faculty Impact Fellowship program to nurture, develop, and retain promising mid-career leaders from across the college’s 13 departments here at the University of Minnesota.

“The college has been challenged in retaining our rising stars as we

face stiff competition from much bigger programs with deeper pockets,” said Sue Mantell, James J. Ryan Professor and mechanical engineering department head.

“CSE departments need a strong college, and a rising tide lifts all boats.”

Faculty Impact Fellows will be supported by these new endowed funds for a period of three years, and they can use the award to advance research, supplement salary, help pay student researchers, or collaborate with scholars around the world.

Invest in innovators and educators.

Establish a new Faculty Impact Fellowship endowment in your name or the name of someone you would like to honor.

Philanthropic gifts or pledges of $350,000+ will be matched 50 cents on the dollar from the University until June 30, 2023. To learn more, please contact Courtney Billing, interim assistant dean for external relations, at cbilling@umn.edu or 612-626-9501.

CRYPTO NOW ACCEPTED University supporters can give using cryptocurrency

Despite the crypto market’s tendency to behave like a roller coaster, experts say it’s here to stay. University of Minnesota supporters can now make cryptocurrency gifts of any size through a secure platform called Engiven.

Donors will be prompted to confirm the transaction in their own cryptocurrency wallet, but are then provided with tax and gift appraisal information, required by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), after the gift is processed.

Cryptocurrency, according to the IRS, “is a type of virtual currency that uses cryptography to secure

transactions that are digitally recorded on a distributed ledger, such as a blockchain.” In other words, think: money routed through a computer network rather than a bank.

There are more than 19,000 different kinds of cryptocurrencies in circulation, with bitcoin and Ethereum among the most popular. As of July 6, 2022, the global cryptocurrency market capitalization—the total value of cryptocurrency—was $904.46 billion.

More info: z.umn.edu/cryptogiving

Let’s talk. MAKE THE MOST OF YOUR YEAR-END GIVING

How to support your favorite CSE cause and save on taxes

If you are considering making a gift to CSE or the University of Minnesota before the end of this year, you may wish to do it in a way that also provides you with tax savings.

Give appreciated assets

Giving securities, such as stocks, bonds, or mutual funds that have increased in value, is a smart way to support CSE. For securities held longer than one year, you may deduct the full fair-market value, subject to applicable limitations. If you do not itemize deductions, you may still benefit by avoiding capital gains tax that would be due upon the sale of the asset.

Give from an IRA IRA owners age 70½ or older can give up to $100,000 directly to charity from their IRA, tax-free. The amount can be excluded from your federal income, lowering your overall tax liability. If you are using an IRA checkbook, the date of gift is established when the IRA administrator transfers the funds after the charity deposits the check, not when the check is postmarked or delivered. Call your administrator soon to ensure your gift is completed by December 31.

Make a gift that pays fixed income for life

You can give cash or appreciated securities to CSE to fund a charitable gift annuity. In return, the University of Minnesota Foundation (UMF) pays you—or up to two people you choose—a fixed annual amount for life.

You receive an income tax deduction for a portion of the gift, and a portion of each annuity payment is tax-free. You also can save on capital gains tax if the gift annuity is funded with appreciated securities. To request a personalized gift annuity illustration with the new higher rates, call 612-624-3333.

Give from a donor-advised

fund

Giving to CSE from your donor-advised fund (DAF) is simple. If you recommend a grant to UMF, your DAF administrator will distribute it directly. Most DAFs also allow donors to recommend the charities that will receive the remaining fund assets after they pass away. If you would like the University to receive all or a portion of the remainder of your fund, please contact your DAF administrator.

Support what’s meaningful to you

You can direct all these gifts to a specific CSE department, center, cause, or program. If you are unsure which option is best for you, or how you want your gift to be used, speak to our team or call the UMF planned giving staff at 612-624-3333.

If you’d like to support a project in this magazine or are curious about other philanthropic giving opportunities, contact us today.

Courtney Billing

Chemical Engineering and Materials Science

612-626-9501 • cbilling@umn.edu

Jennifer Clarke

Industrial and Systems Engineering

Mechanical Engineering 612-626-9354 • jclarke@umn.edu

Anastacia Davis

Electrical and Computer Engineering Institute for Math and its Applications 612-625-4509 • aqdavis@umn.edu

Kathy Peters-Martell

Aerospace Engineering and Mechanics Chemistry 612-626-8282 • kpeters@umn.edu

Brett Schreiner

Corporate and Foundation Relations 612-625-7051 • bschrein@umn.edu

Emily Strand

Computer Science and Engineering Bakken Medical Devices Center School of Mathematics 612-625-6798 • ecstrand@umn.edu

Lexi Thompson Earth and Environmental Sciences 612-626-4040 • lexi @umn.edu

Shannon Weiher

Biomedical Engineering School of Physics and Astronomy 612-624-5543 • seweiher@umn.edu

Shannon Wolkerstorfer

Civil, Environmental, and Geo- Engineering

History of Science, Technology, and Medicine St. Anthony Falls Laboratory 612-625-6035 • swolkers@umn.edu

Golden

Generosity

Scholarship fund by 50-year reunion members marks a decade of helping

When Jean McCallum learned that her alma mater was offering to match $25,000 for a new scholarship fund, she jumped at spearheading one for her reunion class.

“I wanted to help because I had been given a scholarship,” said McCallum, who earned a civil engineering degree from the University of Minnesota in 1959. “It was a whole $500; I know that doesn’t sound like much but back then, it paid for my tuition for two years.”

Through her enthusiasm—and the efforts of others on the Class of 1959’s 50th reunion planning committee— Fund 6290, or the CSE Golden Medallion Society Scholarship, was established. The fund supports students who show “academic promise and financial need.” The first scholarship was awarded in 2012.

As the fund has grown, so have the number of students it supports. Katana “Nina” Davannavong was one such student. The computer engineering major,

who graduated this past summer, first received the scholarship as a freshman.

“My Golden Medallion Society Scholarship was a huge help because it took a great weight off my shoulders,” she said. “I could funnel all my energy into doing my best in school and not worrying about my finances, or how to pay tuition.”

The first-generation college student from Shakopee, Minnesota, is now a software engineer who codes, tests, and maintains the mobile apps associated with newly released products in Medtronic’s Cardiac and Vascular Group.

“Since 6th grade, I knew I wanted to be an engineer,” she recalled. “Medtronic gave a demo at my school and that started my dream of wanting to work with medical devices. I chose CSE because it had so much to offer—so many doors for me to open and discoveries to make. I was also around the best of the best, and I was challenged by faculty and my peers.”

Davannavong’s path to becoming the only woman in STEM in her family resonates with McCallum. Although she had an uncle who was a physicist, she had no family members with an engineering background. That didn’t stop McCallum from pursuing the profession— and neither did the lack of women in the field.

“It’s amazing the number of women who pursue engineering now,” she explained. “There were seven in my class, and by spring quarter, only four of us were left.”

McCallum hasn’t stopped giving to the endowment fund she helped start. She, along with many other alumni, have supported the fund each year since making an

initial gift in honor of their 50th reunion. Anyone can make a gift to the fund, and as it grows, so do the number of Golden Medallion Scholars.

“Donating to a scholarship is a simple gesture, but the impact on students is huge,” Davannavong said. “There’s plenty of me out there, people with family circumstances that don’t allow them to pursue their dream of going to college and wanting to help others. I am forever grateful to the generosity of strangers— everyone who has ever given to this fund.”

Did you know?

The CSE Golden Medallion Scholarship fund is one of nearly 650 endowments in the college, most of which were created by individual donors. To learn more about establishing a fund to support CSE students—or make a gift to an existing fund—call a member of the External Relations team (see page 31).

I am forever grateful to the generosity of strangers—everyone who has ever given to this fund.

“—Nina DavannavongPhoto credit: Nina Davannavong

Our leaders in

United States—and they’re CSE alumni.

“It was during my doctoral thesis, studying with Skip Scriven in the chemical engineering and material science department, that I learned how to do independent research The combination of classroom education, mentorship, and intellectual freedom I received shaped me as a researcher and future faculty member.”

“I had a wonderful and productive time at the University of Minnesota. My adviser, Prof. Suhas Patankar, was a terrific mentor. His great talent was simplicity—how to think clearly and simply about complex things. It is an approach that has served me well as my responsibilities have increased. And I was a part of a warm and collaborative graduate student group; we remain friends to this day!” See more CSE alumni in leadership roles in other U.S. universities at z.umn.edu/academicleaders

billion

FUTURE LEADERS

25 years

ROBERT BROWN WORKED AT MIT, INCLUDING AS PROVOST, BEFORE MOVING ACROSS THE CHARLES RIVER TO LEAD BU

1st

JAYATHI MURTHY IS THE FIRST WOMAN TO EARN A PH.D. IN MECHANICAL ENGINEERING AT THE U AND WOMAN OF COLOR TO LEAD OREGON’S LARGEST PUBLIC UNIVERSITY.

DAWN TILBURY WAS ONE OF THE FIRST CLASS OF HONORS STUDENTS AT CSE.*

PRABHAS MOGHE’S YEARS AT RUTGERS, WHICH INCLUDE MULTIPLE LEADERSHIP ROLES

There’s a growing number of scientists and engineers in academic leadership across the

That’s not all!Brown photo by Scott Nobles for Boston University Photography. Murthy photo credit: Oregon State University.

in Academia

$3.7 billion

SPENT ON RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT THAT FUELS INNOVATION

215,456+

AT THEIR INSTITUTIONS

2

NOEL SCHULZ HAS SERVED AS FIRST LADY AT TWO UNIVERSITIES (K-STATE & WSU)

PRABHAS MOGHE IS THE SECOND HIGHEST RANKING OFFICER AT RUTGERS AFTER THE PRESIDENT.

100%

Minnesotan

DAWN TILBURY GREW UP IN GOLDEN VALLEY, WENT TO ROBBINSDALE COOPER HIGH SCHOOL, AND MAJORED IN ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING AT THE U LIKE HER DAD.

30+ years

EE Ph.D. ’95 • First Lady & co-director of WSU-PNNL Advanced Grid Institute, Washington State University

Former First Lady & Associate Dean for Engineering Research and Graduate Programs, Kansas State University

SCHULZ

“One of the most impactful activities for me at the University of Minnesota was the Women Graduate Students in IT* lunches. The faculty panels and professional development activities provided a foundation for my leadership background and insights into integrating professional and personal activities, as well as resilience through challenges in academic life. Networking with other women graduate students established connections that I still use today.”

ChE Ph.D. ’93 • Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs/Chief Academic Officer, Rutgers University

PRABHAS MOGHE

“The five years spent at the University of Minnesota laid the foundations of my career-long pursuit of interdisciplinary scholarship and inclusive leadership.”

EE ’89 • Associate Vice President for Research & Chair, Robotics Department, University of Michigan

“At the U, I got leadership experience as an ‘IT* Tutor’ and as co-president of the Society of Women Engineers. I was one of the first class of honors students at the college, and I did a research project during my senior year.”

DAWN TILBURY

* The college was known as Institute of Technology (IT) before 2010.

@UMNCSE

UMNCSE facebook.com/umn.cse youtube.com/umncse

When Catherine French arrived at the U like her father and her sisters before her, she was driven by curiosity. Little did she know that her thirst for knowledge would lead to 30+ years as a faculty member, becoming a national leader in building codes for structural concrete systems— and receiving a teaching award named after one of her favorite professors.

The Charles E. Bowers Faculty Teaching Award was established by John Bowers (Physics ’76) to honor his father and noted CSE faculty member. It went to Professor French in 2019.

Consider a gift to support CSE’s innovators and educators: z.umn.edu/supportCSE

“I was an undergrad at the University of Minnesota between 1975 and 1979, and during that time I had the privilege of taking a water resources course with Professor Bowers.”

Nonprofit

U.S. Postage PAID Twin Cities, MN Permit No. 90155

A gift to faculty is a gift to students.

New page!