21 minute read

Recipes: Sweet Potato Shepherd’s Pie

Sweet Potato SHEPHERD'S PIE

CELEBRATE ST. PADDY’S DAY BY ADDING A SOUTHERN TWIST TO THIS TRADITIONALLY IRISH DISH.

Advertisement

RECIPES AND STYLING BY SARAH M c CULLEN | PHOTOGRAPHED BY JOE WORTHEM

Here in America, many celebrate St. Patrick’s Day with traditional Irish food and drink. This coming March 17, try marking the holiday with a festive family dinner featuring shepherd’s pie, but add this decidedly Southern twist: Instead of the traditional topping of mashed potatoes, use sweet potatoes, a crop that thrives in Mississippi, including in nearby Vardaman — known as the sweet potato capital of the world.

sweet potato SHEPHERD'S PIE

4 medium-sized sweet potatoes 2 pounds ground beef, turkey or lamb 1 tablespoon olive oil 1 medium onion 4 stalks celery 1 tablespoon minced garlic 1 tablespoon salt 1 teaspoon black pepper

Preheat oven to 350°F. Bake sweet potatoes whole on a rimmed baking sheet until tender, about 1 hour. Set aside to cool.

In a large ovenproof skillet, cook ground meat until browned; drain meat, and transfer to a plate. In the same skillet, heat oil over medium heat. When hot, add onion, celery and garlic, and saute until tender, about 5 minutes. Add salt, pepper, allspice, rosemary, paprika and chili powder, and cook, stirring occasionally, until fragrant, about 2 1 teaspoon allspice 1 tablespoon rosemary 1 teaspoon paprika 1 teaspoon chili powder 1 (6-ounce) can tomato paste 2 cups chicken broth 1 (12-ounce) package frozen peas and carrots 1 tablespoon butter

to 3 more minutes. Return meat to skillet, and stir in tomato paste and chicken broth. Add frozen peas and carrots, and simmer, about 10 minutes.

Peel sweet potatoes, and beat potatoes and butter with an electric mixer on low speed until mashed. Remove skillet from heat, and gently spread mashed sweet potatoes over the top. Transfer skillet to preheated oven, and bake until bubbly around edges, about 25-30 minutes. Garnish with chopped fresh parsley, and serve.

OPEN FOR BUSINESS

THESE SMALL NORTH MISSISSIPPI BUSINESSES SHIFTED GEARS AND FOUND SUCCESS AMID THE PANDEMIC THANKS TO CREATIVE THINKING AND COMMUNITY SUPPORT.

WRITTEN BY ROBYN JACKSON | PHOTOGRAPHED BY JOE WORTHEM

From restaurants to retailers, small business owners everywhere had to get creative to keep the doors open when the COVID-19 pandemic hit a year ago. Here, a few northeast Mississippi companies — Magnolia Soap and Bath Co. in New Albany, Abe’s Grill in Corinth and Cockrell Banana in Tupelo — share their coping strategies. Continued on page 28

Since it was founded in 2016, New Albany-based Magnolia Soap and Bath Co. has expanded to 16 stores in several states.

GIVE HER A HAND

Magen Bynum introduced the right product at the right time when the novel coronavirus struck last winter and hand sanitizer was in short supply at many stores.

“The COVID thing kind of gave us a scare, but our business actually increased,” Bynum said. “We were able to offer a product that was needed during COVID. It was all the things you need to battle COVID. It was a blessing that we are in the business we’re in.”

Bynum started Magnolia Soap and Bath Co. in New Albany in 2016 after searching for a plant-based alternative to soaps, lotions and laundry detergents for her daughter, Elizabeth Anne, who has allergies to strong scents.

She had planned to debut a hand sanitizer in June 2020, but had ordered the containers and ingredients “on a whim” in January, and everything was sitting in her distribution warehouse.

“Then COVID hit in February, so this was a huge blessing for us because you couldn’t get containers. You literally couldn’t find a container to put hand sanitizer in,” Bynum said.

At the time, Bynum had six or seven retail stores selling only Magnolia-branded products. Now, there are 16 in several states, and two were scheduled to open in February. Some are company-owned, others are franchises. Magnolia Soap and Bath Co. products are also sold in more than 500 boutiques, pharmacies, doctor’s offices and grocery stores nationwide.

“Our soaps are our No. 1 seller,” Bynum said. “We also have a multipurpose disinfectant spray. It’s been a big seller for us.”

Bynum uses only domestically sourced natural ingredients in her products, which offer phthalate-free fragrances for sensitive skin. Her husband, an attorney, has a degree in biochemistry, and he helps her with product development.

They hand pour soaps and candles, hand press bath bombs and hand mix laundry detergent and scents in each store.

“You’re watching us make it, so it’s an experience,” Bynum said. Continued on page 30

MADE FROM SCRATCH

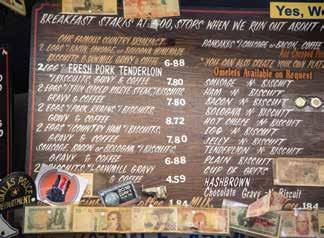

Abe’s Grill is one of those funky little mom and pop places that serves local flavor along with a slice of history. It has been a landmark on Highway 72 in Corinth for 46 years, and is just down the hill from the former site of another landmark, Corona Female College, which was used as a hospital by Union troops after the battle of Shiloh and burned to the ground in 1864.

Antique license plates and signs line the walls inside and out. Specialties include a quarter-pound cheeseburger known as the “Big Abe,” fresh-cut fries, country breakfast plates, buttermilk biscuits made from scratch and homemade chocolate chip cookies.

The restaurant is open from 4 a.m. to 2 p.m. Monday through Friday, and the joint is always jumping.

“We’re busy all the time,” said owner Abe Whitfield. “You can get a barbecue plate at 4 in the morning. We have our first pan of biscuits coming out of the oven at 3:30 a.m.”

When the COVID crisis hit and restaurants were no longer allowed to offer dine-in, closing was not an option for Whitfield and his wife, Terri, and son, Ryan.

“My wife said, ‘Well, we’re going to have to do something; we can’t close up’,” so they converted a window on the front of the building to walk-up service.

“It’s worked out good for us,” Whitfield said. “People call in big orders now, bigger than what they normally did. Everybody’s eating in, so they call in for the office or home. We haven’t skipped a beat.”

COVID hasn’t forced them to scrimp on the quality of their food, either.

“All our food is homemade,” Whitfield said. “Our beef is ground each morning. We make all our sauces and dressings. We make our own barbecue sauce, make our slaw that goes on the barbecue. We don’t use any bagged vegetables, we buy all of them at Rogers Market each morning. We don’t have any frozen food products. We buy all of it local.”

They also get fresh produce from Cockrell Banana in Tupelo and a tomato wholesaler in Tennessee.

Whitfield, 72, said they started closing at 2 p.m. instead of 3 so they could get an extra hour of rest.

“We were so busy in our business before all this happened,” he said. “We’ve got 17 seats. They stayed busy all day. We were having to run up and down the counters, and it was just working the dog out of us.”

Whitfield doesn’t seem to mind.

“Our health is good, we love what we do, and we plan on being here until we drop dead,” he said. “We get all our aerobics right there at the grill. We run all day long; we don’t ever stop.” Continued on page 32

Abe’s Grill, located on Highway 72 in Corinth, is a north Mississippi institution. The diner is open weekdays for breakfast and lunch.

FROM WHOLESALE TO RETAIL

Cockrell Banana Co. has been supplying fresh fruits and vegetables to restaurants, schools, grocery stores and churches in north Mississippi, northwest Alabama and southwest Tennessee since 1930, but when many of those wholesale clients suddenly closed last February and March because of the shutdown, the Tupelo-based distributor began selling produce directly to the public.

“People weren’t able to go to stores,” said Ricky Cockrell, president of the company. “There was fear among everyone. We began doing curbside pickup for produce. We found out people weren’t going to the Walmarts and Krogers. For a number of weeks, people would be here getting their produce through curbside pickup.”

Cockrell said he often spoke to people awaiting their orders.

“They were so thankful; they were so appreciative. There would be lines out there sometimes, and people would have to wait, like at Chick-fil-A, and they’d say it’s OK; they didn’t have anywhere else to go. It was so cool, because I know we really contributed to the community in a really strong way.”

Normally, Cockrell has nine or 10 trucks making deliveries each day, but the company was down to about three trucks a day after the shutdown began. Business was down 70 percent. Selling directly to the public for cash, along with a Payment Protection Program loan, enabled Cockrell to pay his employees.

“It was a win-win,” he said. “It was a win for the customers and a win for us. It really helped us for about two months there.”

Cockrell credits his son and daughter for the curbside idea, and his employees for making it work.

“It took everybody here to make it happen,” he said.

While things are improving, there are still challenges ahead.

“Maybe, slowly, it’s getting better” he said. “I’m like anyone else, I wish it could go back to the old way, but we’re learning to adjust.”

Cockrell Banana Co. has been supplying produce to wholesale clients in north Mississippi for more than 90 years.

BUILDING BLOCKS

A NEW EFFORT AIMS TO EQUIP LOCAL CREATIVE ENTREPRENEURS WITH TOOLS TO SUCCESSFULLY LAUNCH THEIR BUSINESSES — AND TO CONVINCE THEM TO STAY IN OXFORD.

WRITTEN BY ANTONIO BATTISTA | PHOTOGRAPHED BY JOE WORTHEM

The exodus of creative entrepreneurs from Mississippi has become a familiar story. All too often, these artists see bigger cities as greener pastures when setting out to launch their businesses.

The Yoknapatawpha Arts Council, however, wants to help break that cycle with the launch of the Big Bad Business Lab, a new program aimed at giving small art-based businesses a chance to grow to a sustainable size and to create a long-term presence in Oxford.

“We want to challenge our community partners and small business resources to join us in being more vocal about the resources here so that entrepreneurs don’t leave for larger cities where they perceive the network is more vibrant and flourishing,” said Meghan Gallagher, outreach and education coordinator for YAC. “We don’t want our talented Oxonians to slip away.”

The lab, which launched in February, will support a small group of creative entrepreneurs of all mediums — musicians, writers and filmmakers, along with fine, folk, and digital artists — by providing nine

"WE DON'T WANT OUR

TALENTED OXONIANS

TO SLIP AWAY."

-Meghan Gallagher

months of free studio and exhibit space, access to potential seed funding and peer learning opportunities.

Lab participants, who they’re calling cohorts, will receive help setting and achieving key milestones for their businesses, such as finding their first client, launching a new service or building a website.

The idea for the lab grew out of the Big Bad Business series, a free monthly professional development workshop for creative entrepreneurs that has been produced by YAC since January 2017 in partnership with the Oxford-Lafayette County Economic Development Foundation.

The program will be led by creativein-residence Lee Ingram, who has launched two Oxford-based small businesses of his own, Collegiate Tutoring and Lee Ingram Books, and wants to help other creative entrepreneurs build the support system they will undoubtedly need.

“Many young entrepreneurs leave Oxford for bigger cities like Nashville, Houston or Austin, thinking there is more opportunity there,” Ingram said. “But for many, that’s not the case. Unless you have connections in big cities, you can find it hard to be successful.” Continued on page 36

-Lee Ingram

Continued from page 34

As part of the lab, Ingram will walk the artists through the challenges they are facing and help set them up for success.

“Many new business owners and artists may not know where to start,” he said. “It can be as simple as setting up an LLC, getting in contact with a CPA or creating a tax ID.”

Ingram will point the cohorts to professionals in Oxford that can help them with these challenges.

“It means a lot to learn from other business owners who have more experience,” he said. “There are qualified people here that want to help. They care because we are all in the same community. The connections are more personal, more meaningful compared to a big city where you are just another client.”

The lab will also host community events to promote the works of its participants.

“I’m excited to have the opportunity to put a big spotlight on local businesses, local entrepreneurship, the creative economy and the creatives in Oxford,” Ingram said. “We want to tell their stories and highlight the challenges they faced to get where they are.”

Bringing the community into the process is an important part of the lab’s success and will help to highlight the wealth of perks Oxford has to offer for those looking to start a business here.

“You have a huge, wonderfully overqualified pool of people and creatives here,” Ingram said. “Especially if you’re starting out with a business that may end up employing people, I think Oxford is very attractive.”

As the lab gets started, Gallagher encourages the public to interact, learn and grow with the cohorts.

“We want the Oxford community to be on the lookout for events we are going offer to meet the lab artists and hear about their businesses,” she said. “We want the Oxford community to cheer them on during the incubator and throughout their careers.”

The lab will be funded for the next two years by a National Endowment for the Arts Our Town grant. It has also received a $750,000 capital grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The funds will be used to build a space for future cohorts. The building will include a market space, office spaces and studio spaces.

Their future goal is to continue the lab after the initial pilot grant is finished in hopes that more and more creative entrepreneurs will keep their talents and their businesses rooted where they began.

“It’s going to feel great to take that pressure off people,” Ingram said. “This town is so supportive of local businesses. We will get them started so they can let go of their fears and focus on their work. You can succeed here.”

LEARN MORE

For more information on the Big Bad Business Lab, along with topics of monthly workshops and additional online resources and special events, visit oxfordarts.com/programs/ arts-incubator or facebook.com/ BigBadBusinessSeries.

A NEW BOUTIQUE HOTEL IS JUST ONE REASON CLEVELAND, MISSISSIPPI, IS WORTH A VISIT.

Cleveland Renaissance

WRITTEN BY ROBYN JACKSON | PHOTOGRAPHED BY JOE WORTHEM

If your idea of a weekend getaway includes staying in a luxurious hotel, eating delicious food, listening to live music and touring world-class museums, look no further than Cleveland.

At the center of this Mississippi Delta hamlet’s rebirth as a tourist destination is Cotton House, a $17.6 million Marriott Tribute hotel that opened in July 2019 on Cotton Row, the city’s main drag.

“It’s become a great focal point for the city,” said Kelli Davis, director of the Cleveland Tourism Office. “I think the addition of boutique lodging has made it an overnight destination. You’ve got two places to eat there, and restaurants all up and down our main street. People really travel from all over.”

Southern Living named Cleveland one of its best small towns in 2019, and Smithsonian Magazine declared it the No. 2 small town to visit in 2013.

Located on Highway 61 midway between Memphis and Vicksburg, Cleveland began as a sawmill community called Coleman in 1884 when the Louisville, New Orleans & Texas Railroad came through. It began to attract more settlers, and two years later, it was incorporated as Cleveland in honor of President Grover Cleveland, who was said to be on the first train that passed through. The dense forest was cleared for cotton farming and Mississippi River flood control.

Delta State University was founded in 1925 as a teacher’s college. Influxes of Chinese, Jewish, Italian, Irish and Mexican immigrants gave it a cosmopolitan vibe, but when the cotton industry waned, young people moved away. Now, some are moving

Cole Ellis

back and investing in the city, including Chef Cole Ellis, a James Beard Award semifinalist who opened Delta Meat Market in 2013. He moved his restaurant across the street to Cotton House when it opened. He also runs the hotel’s rooftop bar.

“Bar Fontaine is just so nice,” Davis said, citing its views and fire pit. “Cotton House is great for couples, and we’ve had a lot of girlfriend getaways. Hunters come and stay there. It really does appeal to all different audiences.”

Cotton House was developed by LRC2 Properties of Oxford. The project took about four years, including two years of planning and 18 months of construction.

“After many years of visiting the Delta, I developed a love for the unique region and saw the need for a hotel property to match the area’s authentic character,” said Luke Chamblee, LRC2 Properties founder. “I am very proud of Cotton House. It is a beautiful, warm, welcoming property located in the heart of the Delta where we get to show guests true Southern hospitality.”

The decor combines past and present, from the wide plank wood floors to the oldfashioned black rotary-dial telephones in the 95 rooms. The contemporary color scheme is a mix of gray, blue and earth tones. Continued on page 42

Bar Fontaine Delta Meat Market

Delta Meat Market Oxford artist Jessica Perkins’ work is currently on display in the Fontaine Gallery, an exhibit space in the lobby of Cleveland’s Cotton House hotel.

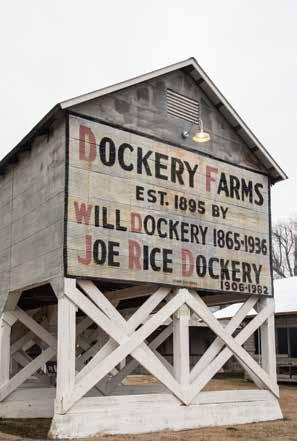

Dockery Farms Balance Fitness

Continued from page 40

“The design team really wanted it to be ingrained in the Delta,” Davis said. “They really wanted to capture the feel of the land around us. The rooms are absolutely beautiful. It’s like you’re in a different world.”

Balance Fitness, a sleek exercise studio owned by Lauren Caston and Georgia Tindall, is located on the ground floor.

The COVID-19 pandemic hit less than a year after Cotton House opened, but Emily Childs, director of sales at Cotton House, said travel is expected to rebound in 2021.

“In the past five years, we’ve seen an increase in demand to travel to this region, which directly impacts Mississippi’s tourism and hospitality industries,” she said.

Blues fans from around the world flock to Cleveland to tour Dockery Farms, which B.B. King declared the birthplace of the blues. Among the famed bluesmen who called Dockery home were

Grammy Museum

Charley Patton, Howlin’ Wolf, Son House and Pops Staples. Visitors learn how the sharecropping system kept Blacks in poverty and led to the Great Migration north, where jobs and opportunities beckoned. There’s a restored cotton gin and the commissary where musicians gathered on the porch to play at the end of a long day picking cotton. It’s one of 19 stops on the Mississippi Blues Trail in Bolivar County.

Cleveland’s importance to the blues led the Grammy Museum in Los Angeles to open its second museum in Cleveland in 2016. It includes interactive exhibits on a variety of musical genres, documentary films and memorabilia from artists.

The Martin and Sue King Railroad Heritage Museum features the largest O-gauge model railway in the state, and the Mississippi Delta Chinese Heritage Museum explains how families moved from China to the flatlands of the American South.

The blues might feed the soul, but there’s no lack of tasty soul food in Cleveland.

In addition to Delta Meat Market,

which serves Southern cuisine with locally sourced ingredients, foodies gravitate to The Senator’s Place, which was opened in 2003 by Mississippi Transportation Commissioner Willie Simmons, who served in the state Legislature for 27 years. Everything is made from scratch, from smoked chicken and cornbread dressing and gravy to peach cobbler. Country Platter Restaurant offers fried chicken and other traditional Southern dishes in the former Lilley’s Soul Food Cafe building, where Martin Luther King Jr. and Medgar Evers met with local business leaders in the 1950s and 1960s. Airport Grocery began during the Great Depression as a grocery store. Now, in addition to catfish po’boys, hot tamales, gravy fries and ribs, it boasts pool tables and a full bar. Hey Joe’s burgers and beer joint and Mosquito Burrito are owned by local musician Justin Huerta.

“Keep Cleveland boring,” a nonprofit organization’s tongue-in-cheek slogan encourages residents, but Cleveland is anything but boring these days.

Hey Joe's