7 minute read

THE STATE OF STEWARDSHIP IN THE CORE STATE

This is the third of several articles that explore the findings of the recent Working in the Public Service survey by taking a deep dive look at stewardship – one of five principles in the Public Service Act 2020.

We explore whether stewardship is a magic concept that is broad in scope, has positive connotations that are hard to oppose, are rhetorically useful but impossible to assess and measure. Much of the Public Service Act description of stewardship is simply ‘old wine in new bottles’, repackaging what used to be called the capability dimension of the ownership interest. However, an examination of central agency websites suggests that stewardship is more than a big word that is conceptually ambiguous. In particular, the concepts of regulatory stewardship and policy stewardship add new dimensions to thinking and productive ‘recipes for action’ that were not addressed by the reforms of the 1980s and 1990s. Moreover, chief executives’ roles go beyond merely supporting their ministers to include acting independently as stewards.

Our survey struggled to operationalise the principle of stewardship

In the Working in the Public Service survey, as we discussed in the last edition, we focused on five principles: political neutrality, free and frank advice, merit-based appointments, open government, as well as stewardship. The survey focused on employees’ perceptions of how these public service principles are operating in practice.

Defining stewardship for the survey proved particularly problematic. The survey questions on the stewardship principle focused on the tension between short-term priorities and longer-term imperatives. The definition used in the survey was “Stewardship is maintaining and enhancing the capability

Derek Gill

to think, plan and manage in the interests of the citizens and governments of the future. It includes knowledge, human capital, physical and financial resources, and keeping legislation up to date”. This drew on the Public Service Act 2020, which describes stewardship using five dot points detailed below, covering people, knowledge, systems, assets, and legislation.

The ambiguity around the meaning of stewardship was reflected in the range of views among respondents. The graph below shows that slightly more respondents felt that their agency finds the right balance between short-term priorities and longerterm progress and stewardship (53 percent agreed; 39 percent disagreed; 4 percent didn’t know).

By contrast, looking at their own work, more respondents disagreed than agreed statement that, in their job, they can usually devote enough time to longer-term into the public administration literature in the last decade. Interestingly, the State Service Commission’s (SSC) 1995 Public Service Principles, Conventions and Practice: Guidance series explicitly refers to public servants’ stewardship role. “Public servants are required to use resources efficiently, effectively and economically (State Sector Act 1988, s32) and to account publicly for their stewardship as prescribed in the Public Finance Act 1989.”

By contrast, looking at their own work, more respondents disagreed than agreed with the statement that, in their job, they can usually devote enough time to longer-term matters rather than just short-term issues (52 percent disagreed, 45 percent agreed, 4 percent didn’t know).

By contrast, looking at their own work, more respondents disagreed than agreed with the statement that, in their job, they can usually devote enough time to longer-term matters rather than just short-term issues (52 percent disagreed, 45 percent agreed, 4 percent didn’t know).

However, this usage was not widespread until it was adopted into the State Sector Act in 2013. Stewardship has now also been adopted in the legislation for the public service of Australia as well as the code of conduct in Canada.

The New Zealand Public Service Act 2020 lists the resources that need stewardship as “including— i. its long-term capability and its people; and ii. its institutional knowledge and information; and iii. its systems and processes; and iv. its assets; and

Source: BusinessDesk / IPANZ research v. the legislation administered by agencies.”

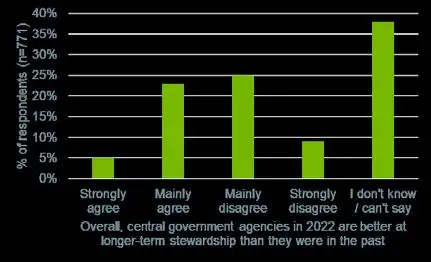

Respondents were also spilt about whether central government agencies in 2022 are better at longer-term stewardship than they were in the past (28 percent agreed; 34 percent disagreed; 38 percent didn’t know).

Respondents were also spilt about whether central government agencies in 2022 are better at longer-term stewardship than they were in the past (28 percent agreed; 34 percent disagreed; 38 percent didn’t know).

While the Act leaves stewardship undefined, the Public Service Commission’s website provides various overlapping explanations, including an emphasis on fiduciary issues, “acting as stewards or caretakers for a resource that belongs to or exists for the benefit of others”, where resources paraphrase the Public Service Act’s five points above. The website also suggests that stewardship involves public servants “taking active steps” and, in some cases, even acting independently of ministers.

The Cabinet Manual has been amended and updated to reflect the legislative regime applying to the public service. It now discusses chief executives and their agency’s stewardship role and the need for ministers to accept stewardship advice from an agency chief executive. It is silent, however, on the minister having any stewardship role. For example, on legislation, the minister’s role is limited to the introduction of new laws – a set-and-forget approach – with no mention of a responsibility for oversight of the stock of existing primary and secondary legislation.

Source: BusinessDesk / IPANZ research

Stewardship as a magical concept?

Stewardship is an old word but is a relatively new term in public management

Stewardship is an old word but is a relaFvely new term in public management.

Rodney Scott and Eleanor Merton, in a comprehensive background paper on the Public Service Commission website, note, “The term steward is generally thought to be derived from the Proto-Germanic stiġ weard, to refer to a domestic servant (weard) who maintains a house or hall (stiġ).” Stewardship as a general public management concept is more recent. Stewardship theory in management can be traced back to 1997 and first came

Rodney Scott and Eleanor Merton, in a comprehensive background paper on the Public Service Commission website, note that, “The term steward is generally thought to be derived from the Proto-Germanic stiġ weard, to refer to a domestic servant (weard) who maintains a house or hall (stiġ)”. Stewardship as a general public management concept is more recent. Stewardship theory in management can be traced back to 1997, and first came into the public administration literature in the last decade. Interestingly the State Service Commission (SSC)’s 1995 Public Service Principles, Conven7ons and Prac7ce: Guidance series explicitly refers to public servant’s stewardship role. “Public servants are required to use resources efficiently, effectively and economically (State Sector Act 1988, s32) and to account publicly for their stewardship as prescribed in the Public Finance Act 1989.”

Christopher Pollitt – one of the world’s leading thinkers on public management – defined the term ‘magic concept’ to cover big words which are conceptually ambiguous. Stewardship has many of the characteristics of a magic concept. Magic concepts in public administration are “very broad, normatively charged and lay claim to universal or near universal-application” (Pollitt and Hupe, 2011, p.643). They outline four characteristics of a magic concept in public administration using the terms governance and accountability as examples:

1. Broadness: they are widely applicable and have a wide scope.

2. Normative attractiveness: overwhelmingly positive connotations, it is hard to argue against them.

3. The implication of consensus: they obscure conflicting interests and logic.

4. Marketability: the concept is known and used by practitioners and academics, frequently appearing in communications material and referred to as solutions.

On the face of it, stewardship, much like the terms ‘governance’, and ‘accountability’, has many of the characteristics of a magic concept: broad in scope, positive connotations that are hard to oppose and rhetorically useful.

Old wine in new bottles? Comparing the ownership interest and stewardship

Another critical perspective on stewardship is a reflection on how it differs from the concept of the ownership interest, which underpinned the New Zealand public sector management reforms. Specifically, the reforms in the State Sector Act 1988 and the Public Finance Act 1989 embodied the separation between the government’s purchase interest in the delivery of services (outputs) from the ownership interest in any public agencies that might deliver those services. The purchase interest was more readily and sharply defined than the ownership interest, while the government’s interest in regulation wasn’t addressed at all.

Researchers have looked into the question of whether stewardship is a magic concept. Marsh et al., looking from an Australian perspective, find stewardship has “many characteristics” of a ‘magic’ concept. Rosalind Coote, in her forthcoming Doctor of Government thesis, concludes that in a New Zealand context, it is not. The latter is on the grounds that in a range of domains, stewardship has provided ‘recipes for action’, something Pollitt and Hupe suggest magic concepts do not support. Her research examines how stewardship has been used as a framing idea for collective action in the New Zealand public service.

As part of the development of the reforms, a Chief Executive group described ownership as having four “requirements”: strategic alignment with government priorities, the integrity of the public service, assurance of future capability, and costeffectiveness over the long run (Interdepartmental Working Group on Ownership, 1995). The State Services Commissioner of the time defined capability as “…the quality, quantity, and interaction of the resources – the people, finances, and stock of knowledge – that form the fabric of any organisation; and the values, systems, structures, and leadership that bring those resources together and apply them” (Wintringham, 1998, p. 7). With the exception of regulatory stewardship of “the legislation administered by agencies”, the then Commissioner list is strikingly similar to the description of resources needing stewardship in the Public Service Act 2020.

Stewardship in action?

To explore whether stewardship in the public sector management domain has provided ‘recipes for action’ or provided a new perspective (compared to the ownership interest), I examined three central agencies websites. I limited myself to searching for the terms ‘stewardship’ and ‘ownership interest’ to see what I could locate. Stewardship is the new ‘it’ word. The question being addressed was the counterfactual history question: if the concept of ‘stewardship’ had not replaced ‘the ownership interest’ in central agency jargon, what would be different?