12 minute read

The Judge Who Fought The Law For The Right To Parade In Perth For St. Patrick’s Day

The judge who fought the law

FOR THE RIGHT TO PARADE IN PERTH FOR ST. PATRICK’S DAY

Advertisement

BY LLOYD GORMAN

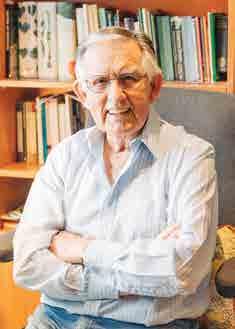

By every measure Irish born Walter Dwyer was a man of impeccable character, a model citizen who made an enormous contribution to Western Australia. But there was one notable situation in his life when the proud Irishman and Catholic sided with his heritage and beliefs to openly defy the law. Dwyer was born in August 1875 in Carrick-on-Suir, Tipperary where he lived until he was sixteen, at which age he emigrated to Victoria where he worked as a teacher. Like tens of thousands of other hopefuls he came to Western Australia in about 1895 in the hope of finding his fortune in the gold rush. Instead he studied law and found employment in Kalgoorlie and Boulder before he went onto Perth to complete his studies and practice law first back in Kalgoorlie and Boulder in 1907 and then Perth in 1910. Dwyer was a rising star and cut a dashing figure in court. He was tall, handsome and very good at public speaking and argument with more than a touch of an Irish accent about him. These skills also served him well for politics and in 1911 he won the Perth seat in the Legislative Assembly, the first time the city seat had ever been taken by a Labor candidate. In 1912 alone Dwyer was instrumental in drafting the Industrial Arbitration Act and getting the Money Lenders Act – which gave borrowers protections – and the Landlord and Tenant Act through parliament. He also got married in 1912 to one Maude Mary, the daughter of a WA pastoralist. Despite his achievements Dwyer was not re-elected Left: Walter Dwyer. Above: Crowds of people in Hay Street in 1916 after a military parade

to the seat in the 1914 election, something he came to regard as a blessing in disguise. In January 1915 Dwyer joined forces with John Patrick (JP) Durack – another prominent WA family of Irish origins – to form their own practice Dwyer and Durack. A West Australian newspaper report for March 20, 1914 gives a good insight into how ‘Irishness’ of Perth at the time. The fact that St. Patrick’s Day fell that year on a Tuesday did not dampen the scale or size of celebrations. “Tribute had to be paid to the memory of the patron Saint of Ireland, and workaday trifles were set aside remorselessly for the occasion,” the journalist wrote. “Mangers, artisans and office boys, boasting but the remotest of Irish ancestry, contrived excuses to break into the routine of every-day existence and do their share in the celebrations – flourish the green with the ostentation of a great national pride, and, if possible, fall into line for the procession... So the patron saint was a might influence in the city on Tuesday. His virtue and

his evangelical seal were acknowledged at all places and in all manner of ways – sometimes with copious draughts of that which stirs the mind and expands the heart, but mostly with orderly and systematic displays or the wearing of a little private rosette. “The streets were a riotous picture of green, and the general colour scheme was carried out alike in the

point in time. It came just months before the start of World War I and as such is an unblemished account about the St. Patrick’s Day parade in Perth. Just before the onset of ‘The Great War Ireland’ had been reluctantly promised a measure of independence by the British Government. But the outbreak of the war interrupted that from going ahead as planned. Home Rule would be delivered after the war the British The main corners of the route were more government said and the men of or less impassable through the number of Ireland were encouraged to enlist in the British Army to help bring the spectators which the procession attracted conflict to an end. and the tram service, and other conveniences The politics of Ireland, Ireland and had to yield to the popularity of St. Patrick.” England and even Australia – which also had a national debate about conscription – changed dramatically demure piece of ribbon the bosom of the little Irish girl, the blatant buttonhole of the patriot, who was off for the day, and even in the streams of ribbon from the cab-horses’ mane. The city was soon full of family parties, bedecked copiously with green – for if Pat could not get off, his missus managed to suspend household operations and give the youngsters a treat after the events of the Easter Rising in April 1916, including the brutal execution of the Rising leaders. The patriotic allegiance of Australia’s Irish community towards the country – and by extension Britain and the Monarchy – which despite many Australians at the time still considered to be ‘The Motherland’ – were called into question. in the city. CONTINUED ON PAGE 10 “The special attractions were, as usual, the street procession and the sports at Claremont (Oval). The weather was delightful and the procession was carried out according to the ambitious expectations of the committee. Not only did it make up a much larger gathering than that of last year, but it was a spectacle of exceptional splendour, and contained a TUESDAYS at the Woody few features which must have demanded not a little ingenuity and effort in the preparation.” The newspaper outlined the city centre route taken by the parade, which dispersed at the train station IRISH MUSIC SESSION 7-11pmso that people could get to Claremont for the next phase of the celebrations. “The main corners of the route were more or less impassable through the number of spectators which the procession attracted and the tram service, and other conveniences had to yield to the popularity of St. Patrick.” $15 PIE & PINT NIGHT $6 PINTS OF GUINNESS FROM 6PM It also described the parade and displays in some detail and those taking part. Bringing up the rear of the procession of pipe bands, floats and marching groups as well as at least 3,000 school children Woodbridge Hotel was the Archbishop and some other VIPs in a horse 50 EAST STREET, GUILDFORD drawn jaunting car. 9377 1199 The report for the Perth parade is from an interesting

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 9

There were ongoing tensions back discussed at some length a For his part Dwyer was in Ireland and across the then recommendation of the general prosecuted, convicted and fined British empire which had an Irish purposes committee that the ten shillings for breaching the population and St Patrick’s Day programme of St. Patrick’s Day peace, which he refused to pay. parades became embroiled in the procession be submitted before The unapologetic lawyer only heated politics of the day. permission to parade be granted,” escaped jail because someone In her article “Spectacles of splendour: St. Patrick’s Day in wartime Perth” on irishaussies. wordpress.com, Lynda Ganly states that Dwyer got involved in the organisation of the parade and events for St. Patrick’s Day. “Dwyer’s 1917 speech was rousing,” she writes. “In it, he described the nature of the Irish people and their history. He described St. Patrick’s Day as a day of religious celebration as well an article (most likely syndicated to newspapers across Australian) in the Goulburn Evening Penny Post for February 27, 1919 said. “Councillor Butt said certain streamers and emblems in last year’s procession had given offence to many in the community, and that sort of thing ought not to be tolerated. Ultimately a resolution was carried to the effect that the council was only prepared to grant permission for else paid the fine on his behalf. Dwyer was fêted at a celebratory function in the Celtic Club. “The tribute to Mr. Dwyer was something more than a mere personal affair – it was an emphatic protest against the action of the city council in its attempt to restrict the rights of Catholics and Irishmen to walk in procession, and to carry their national emblems on the feast as of political and national pride. He outlined Ireland’s struggles and attributed them to its lack of political independence. His speech was a call for independence, yet at no point did it call for violence; Dwyer ended his speech “ ...the council was only prepared to grant permission for processions in streets of Perth on the understanding that at the head of such procession two average size flags, the Union by reminding the crowd that Irish people should be peaceful, Jack and the Australian Flag...” and he hoped that ‘sympathy and understanding’ would be undertaken by the British with regards to Ireland. This speech was not the only evidence of emboldened Irish pride in Perth and the Irish community in the city seemed unafraid to proclaim their devotion to Ireland. processions in streets of Perth on the understanding that at the head of such procession two average size flags, the Union Jack and the Australian Flag, measuring about six feet by three feet each, must be carried unfurled, and that full programme of the procession giving route, details of banners, day of of St. Patrick,” an article with the headline ‘Great Irish gathering in Perth – Mr W Dwyer honoured’ in the Southern Cross Adelaide for July 25, 1919 said. “And a more emphatic protest there could not have been. The speech delivered by his Grace Archbishop Clune roused the In one December 1917 article in flags, signs, streamers, tableaux, temper of the gathering, and his the The W.A. Record, journalists or emblems be first submitted to trenchant criticism of the illand politicians in Australia were the council for approval.” advised action of our City Fathers accused of misrepresenting Irish It is not quite clear what the evoked the heartiest approval. people, describing an ‘anti- ‘offending’ material in question The audience was a most Irish campaign’. The author was but it may have had representative one, and ‘the hall then declared that the Irish in something to do with demands was uncomfortably crowded from Western Australia had nothing to for Home Rule for Ireland. In any the stage to the front doors’.” be ashamed of and were just as case, the parade – led by Walter Australian as their neighbours”. Dwyer – went ahead in defiance Events came to a head in Perth in of the councils orders prohibiting CONTINUED ON PAGE 12 1919. the march. A massive crowd “Last night the City Council turned out to support the parade.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 10

Dwyer did not disappoint. “The action of the city council towards St. Patrick’s Day procession of this year...is so contemptible, so ridiculous, so small, so mean that words really fail to express our feelings towards it. You will remember that a little while before we began our movement there was a telegram from Melbourne that the City Fathers there intended to impose ridiculous conditions on the St. Patrick’s Day procession there, and that certain flags were to be carried. About the same time, apparently, this electric wave from Melbourne must have reached the minds of the City Council here, because we find our City Fathers requiring the same conditions as the City Council in Melbourne. It may be a mere coincidence but it looks to me something more

than a coincidence, something that was planned. I believe that in Melbourne when the Eight Hours Day procession intended to march n their own way, they bowed their heads and allowed the procession to pass without further discussion. I remember, as regards the St. Patrick’s Day Committee, there was only one object in our minds of how the action of the City Council can be met, and it was by ignoring them – (applause) – and throwing the letter of the City Council clerk into the wastepaper basket, a proper receptacle”. The toast of “Ireland a nation” was briefly submitted by Mr. T. Slattery, and eloquently responded to by the Rev. Father Neville, O.M.I. Father Nevilles’s response won the hearts of the great gathering – it was a grand effort and his reference to the men of Easter Week brought out great resounding cheers, which left no doubt as to the love and reverence of the gathering for the dead who died for Ireland during the stormy Dublin days in Easter, 1916.” A short article headlined ‘Celebrations in Perth’ in the Kalgoorlie Miner on March 18, 1920 tells us more about how a solution to a possible repeat of the situation was found ahead of the parade for that year. “St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in Perth today (dated March 17) were marked with the keen enthusiasm characteristic of the Irish community, who turned out in full

force to take part in the festivities. Last year’s little difficulty with the City Council regarding the procession died a natural death with the passage of the new Traffic Bill, under which the control of the traffic passed to the Police Department. For today’s display the path of the procession through the streets was cleared by mounted police. The sports programme was subsequently carried out on the WA Cricket Association Grounds.” Ms Ganly wrote: “[The police department] ruled to allow the St. Patrick’s Day parade without restrictions in 1920, and according to newspaper reports, it was a great success. Following the Mr Dwyer in later years

legalisation of the parades, the Irish community in Perth no longer had to campaign to celebrate their heritage; they were free to embrace both their Irish and Australian identities equally.” Just over a week after St. Patrick’s Day 1950, Dwyer died at the age of 74 in a hospital bed in St John of God Hospital Subiaco and was buried at Karrakatta Cemetery. In his life he went on to become a founding trustee of the State Library of Western Australia, Western Australian Museum and the Art Gallery of Western Australia and was even knighted the year before his passing for his service to the law. For all these accomplishments it is tempting to speculate that he always harboured a spot in the wilds of his Irish heart for his rebellious stance on the St. Patrick’s Day parade as one of his favourite achievements.”