4 minute read

In Judgement of Joyce

BY LLOYD GORMAN

Acclaimed as one of the greatest works of literature James Joyce’s Ulysses also has a lot to offer those with an interest in the law and things legal. In fact the mammoth novel (based on the activities of its protagonists on June 16 1904) references 32 different court cases, 18 of which were criminal cases, many of which were tried in Dublin between 1899 and 1926. The shadow of political trials can also be felt, including for Nationalist Irish leader Robert Emmet in 1803 and the trial of the Invincibles in 1882 for the murder of the Chief Secretary of Ireland in Dublin’s Phoenix Park. Finnegans Wake - his successor to Ulysses - in particular, as well as other stories by the Dublin born author are not unlike legal documents in their own way. Legions of academics and literature lovers have forensically analysed Ulysses since its publication in Paris on Joyce’s 40th birthday, February 2 1922. His work has also found a certain following in the legal fraternity. The late Supreme Court judge in Ireland Adrian Hardiman was a devotee of Joyce. A keen writer, historian and fluent Irish speaker Hardiman also served on the Supreme Court from 2000 until his death in 2016, aged 64. His career was marked by his steadfast defence of civil liberties and individual rights and his constant preparedness to curtail any potential abuse of power by an Garda Síochána. His first book ‘Gandhi in His Time and Ours: The Global Legacy of his Ideas’ was published in 2003. His second book ‘Joyce in Court’ was brought into print in the 12 months after his death. Joyce was fascinated by and felt passionately about miscarriages of justice, and his view of the law was coloured by the potential for grave injustice when policemen and judges are given too much power. Hardiman recreated the colourful, dangerous world of the Edwardian courtrooms of Dublin and London, where the death penalty loomed over many trials. He also brought to life the eccentric barristers, corrupt

Advertisement

police and omnipotent judges who made the law so entertaining and so horrifying. American lawyer Joseph Hassett has shared his love of law with his

The bigger they are, the harder they fall passion for Irish culture. Apart from the fact the University College Dublin and Harvard law graduate is counsel to the Irish embassy in Washington he is also an enthusiast of William Butler Yeats and James Joyce. In his tome The Ulysses Trials: Beauty and Truth Meet the Law Hassett looked at the banning of Joyce’s masterpiece in America and the feeble attempt to defend it in court. ‘Joyce and the Law’, edited by Jonathan Goldman and published by Florida Press, draws together brilliant legal and academic minds to deconstruct the works of the Irish writer from a diverse myriad of legal perspectives.

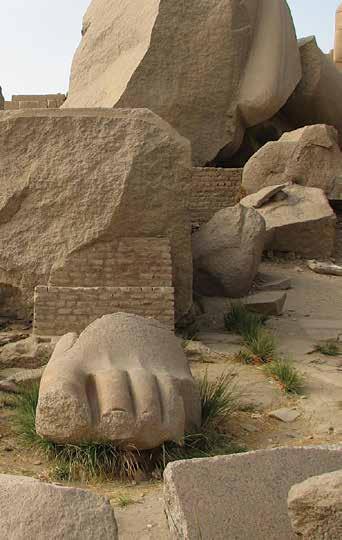

Many readers who went to secondary school in Ireland will recognise the following poem from their ‘Leaving Cert’ days. I know in my case it is thirty years since I studied it in fifth or sixth year and by that stage it was already a classic chestnut that generations of Irish students had to try and crack. Incredibly it is still on the syllabus, popping up again for the 2021 academic year. Anyhow, in light of recent events around the world it is worth sharing its ancient perspective on the vanity of statues. Percy Shelley wrote this little literary nugget in 1818, about the arrogance and self importance of great leaders, not long after the fall of the great Napolean Bonaparte in Europe. The figure of Ozymandias in the poem is Pharaoh Ramesses II, who ruled Egypt (and an empire) for 66 years more than a thousand years before Christ was born. The statue in Shelley’s poem - rather

Top: The remains of the Ozymandias statue. Left: The book ‘Joyce and the Law” by Jonathan Goldman. Far left: Joseph Hassett

than ruined remains - once stood 57 feet tall. “Ozymandias” by Percy Bysshe Shelley I met a traveller from an antique land, Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand, Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown, And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, Tell that its sculptor well those passions read Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed; And on the pedestal, these words appear: My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings; Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair! Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away.”