TheIrrawaddy

MECHANICS FORCED TO RETOOL AS NEWER CARS FLOOD MYANMAR’S MARKET

MYANMAR’S MULTICULTURAL SPIRITS

PEACE BE DAMMED

LESSONS OF ‘88

Cartoons Features

MECHANICS FORCED TO RETOOL AS NEWER CARS FLOOD MYANMAR’S MARKET

MYANMAR’S MULTICULTURAL SPIRITS

PEACE BE DAMMED

Cartoons Features

The Irrawaddy website receives more than 80 million hits each month. In 2010 we had more than 5.2 million website visits—averaging 650,000 visits and 2.2 million pageviews per month. More than 180,000 unique visitors from 200 countries worldwide access our website every month. Visits from readers inside Myanmar have tripled since the early 2012.

www.irrawaddy.org

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Aung Zaw

MANAGER : Win Thu

The Irrawaddy magazine covers Myanmar, its neighbors and Southeast Asia. The magazine is published by Irrawaddy Publishing Group (IPG) which was established by Myanmar journalists living in exile in 1993.

EDITOR (English Edition): Kyaw Zwa Moe

COPY DESK: Neil Lawrence; Paul Vrieze; Samantha Michaels

CONTRIBUTORS to this issue: Aung Zaw; Kyaw Zwa Moe; Saw Yan Naing; Marwaan Macan-Markar; Samantha Michaels; Min Zin; Kyaw Phyo Tha; Dominic Faulder; Sean Havey; William Boot; Simon Roughneen; Virginia Henderson; David Gilbert

PHOTOGRAPHERS : JPaing; Steve Tickner

LAYOUT DESIGNER: Banjong Banriankit

REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS MAILING ADDRESS: The Irrawaddy, P.O. Box 242, CMU Post Offi ce, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

YANGON BUREAU : No. 197, 2nd Floor, 32nd Street (Upper Block), Pabedan Township, Yangon, Myanmar. TEL: 01 388521, 01 389762

EMAIL: editors@irrawaddy.org

SALES&ADVERTISING: advertising@irrawaddy.org

PRINTER: Chotana Printing (Chiang Mai, Thailand)

PUBLISHER : Thaung Win (Temp-1728)

14 |

Border: Peace Be Dammed

After years of ethnic conflict, people in eastern Myanmar’s border regions now have a new worry: recently restarted dam projects on the Thanlwin River

18 | Regional: The Die is Cast: Buddhist Sri Lanka Faces a Casino Choice

Efforts to give Sri Lanka’s tourism industry a boost run up against opposition from the country’s moral guardians: Buddhist monks

20 |

Society: Myanmar Patients Pay the Price

Reform is underway, but the country’s neglected health-care system offers no quick fixes

26 |

COVER Why the Past Can’t be Put to Rest

The parents of a girl who was killed by Myanmar’s army in 1988 say their daughter will only rest in peace when real democracy is restored

30 |

COVER Lessons of ‘88

The failure of the 1988 uprising points to the challenges Myanmar faced then, and still faces today

34 | Business: Mechanics Forced to Retool as Newer Cars Flood Myanmar’s Market

After decades of working on nothing but clunkers, Myanmar’s mechanics must now try to catch up quickly with the latest in automotive technology

38 | Business: Airlines Scramble to Land in Myanmar, but Visas Still up in the Air

There are more ways than ever to fly to Myanmar, but actually entering the country can still be a complicated business

|

Serge Pun may have lost his bid for a lucrative telecoms deal, but he still expects to win big as Myanmar’s economy opens up

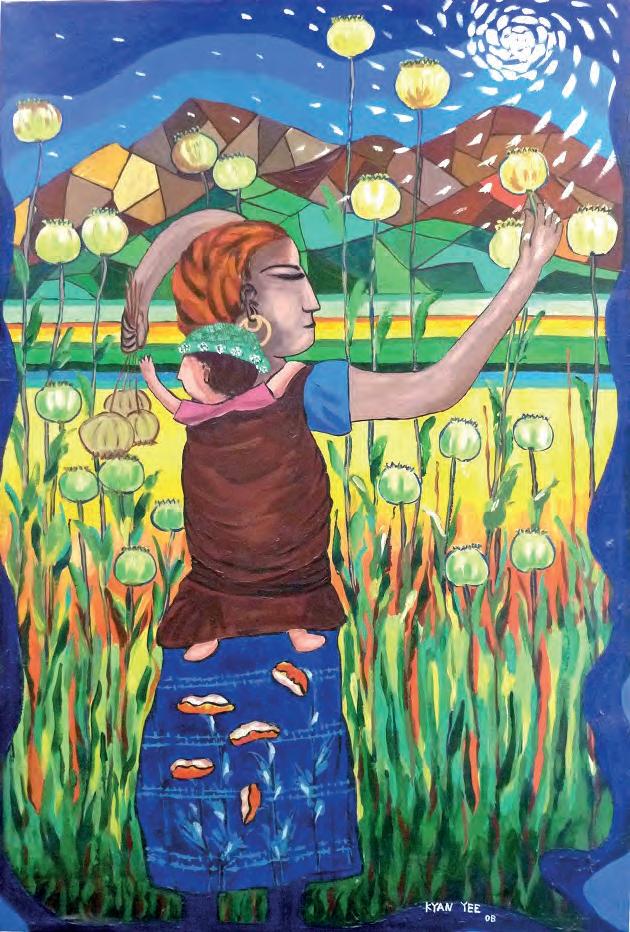

46 | Culture: Mandalay’s New Day

A celebrated Myanmar artist uses his gifts as a teacher to reawaken a taste for freedom in a new generation

This August marks the 25th anniversary of the nationwide protests in 1988 that launched Myanmar’s pro-democracy movement. As one of the most prominent leaders of that uprising against military rule, Min Ko Naing was forced to spend most of the next two and a half decades in prison. Released in early 2012 along with many other fellow political prisoners, he has since returned to public life as a founding member of the 88 Generation Peace & Open Society, a group dedicated to restoring democracy and human rights in Myanmar.

Min Ko Naing is a nom de guerre meaning “Conqueror of Kings”, and it has become synonymous with the determination of the people of Myanmar to end unjust, autocratic rule. But these days Min Ko Naing is also actively seeking national reconciliation, even as he continues to push for accountability for human rights abuses committed in the country. However, as he says in this interview with The Irrawaddy’s Kyaw Zwa Moe, his quest to uncover the truth about the past is not about seeking revenge.

Min Ko Naing has won numerous international awards for his activism. These include the 2009 Gwangju Prize for Human Rights; the 2005 Civil Courage Prize; the 2001 Student Peace Prize; the 2000 Homo Homini Award of People In Need; and the 1999 John Humphrey Freedom Award. His most recent honor was an award from the US National Endowment for Democracy, which he received in 2012.

Twenty-five years after the 1988 pro-democracy uprising, what do you think the movement has achieved so far?

Certainly, they [the authorities] now have to shout louder than we do about democracy. Whether they are really practicing it or not is another matter. The situation today is that they now have to admit that the banner of democracy that we raised is righteous and noble. Here, I think we need to examine what kind of political reform is taking place in this country—is it for all of the people, or just for a group of people?

The important question is: who is this current change for?

Back in 1988, many democracy activists, including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, called the pro-democracy movement the country’s second struggle for independence. Is it still the same struggle today?

Unlike the past, the other side is no longer denying democracy. But things are not moving smoothly, so we still have to struggle. Sometimes, we have to compete with them and sometimes we have to negotiate with them. After all, it is still a struggle.

It will be very difficult to achieve reconciliation in Myanmar without compromising on the issue

of justice. How will the 88 Generation Peace & Open Society seek justice for those who have suffered for their role in the struggle?

I think we can bring about both—justice and reconciliation. Of course, it is essential to reveal the truth. We can learn lessons from the past only if we uncover the truth. But this doesn’t mean seeking revenge. So first we have to disclose the truth, and then we have to take responsibility together to ensure that injustices don’t happen again.

These days, we can see many media reports about human rights violations in the past. So far, I haven’t seen any actions taken by the authorities against those publications. I think it’s all part of disclosing the truth, although we still can’t pursue it as a nationwide mission.

Your group has decided to make peace and reconciliation the theme of its commemoration of the 1988 uprising. Why did you choose that topic?

Peace and reconciliation are essential if we want to move forward. At the same time, however, we will also organize exhibitions about what happened in the past, to continue to disclose the truth.

Myanmar’s opposition groups always had trouble dealing with the political games of the former regime, and they are still lagging behind the current government in terms of strategy. Why are the opposition groups so weak at formulating and following strategies?

I don’t see politics as a game. Eventually, politics [in Myanmar] will become a game in which there are players. But right now we are freedom fighters, not players in a political game. I don’t know the rules of that game. Dhamma [justice] will prevail over Adhamma [injustice] in the end. But it also depends on our might and unity. Unity is not a problem in a dictatorship because it is always a top-down system. But in a democracy, everybody is allowed to be different. That is the nature of democracy.

The people of Myanmar are looking to the 88 Generation for

leadership at this critical time. What is the political agenda of the group?

I don’t want people to depend on an individual person or group. I think we need collaborative leadership. We are now trying to empower civil society, which is different from forming political parties. I think the civil society groups are getting stronger and stronger. What we are doing today is building a network. You can’t see a single tree standing out in a field. Our work is horizontal, not vertical.

Will you form a political party to contest the 2015 national election?

Personally, I have no plan to form a political party. But in our group, there are some who are keen to do so and capable of making it work, so they might form a party at some point. I understand why they want to do it, but as for me, I don’t have any enthusiasm or aptitude for it.

Let me say a few words about party politics and people’s politics. Those two ideologies always divide us into two

groups. Look at Bogyoke Aung San: He formed a party, but he wasn’t really doing party politics. Instead, he engaged in people’s politics for the good of the whole nation.

I won’t form a political party, but I will keep working at the grassroots level. Look at people like Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. We don’t criticize them for not taking part in party politics. Their work was hugely influential. So I don’t think that that forming a political party and running in an election is the only way to achieve things in politics.

How do you propose to change the current political situation in Myanmar, in which former military leaders still dominate in both the government and the Parliament?

It would be best if power was in hands of the people. To reach our goal, I am more interested in influence than power. After 50 years of being ruled with an iron fist, our people tend to think of power as something used to oppress them. It was power that

intimidated and enslaved them. The way governments took or seized power wasn’t right, either.

That’s why I want to apply influence rather than power. By building influence, we will be able to put power into hands of the people.

What is the difference between the struggle you started in 1988 and the challenges you face today?

In the past, our struggle faced total denial and a closed door. So we had to put all our energy into opening that door. Now the door is open and we’ve received promises [from the authorities] that they will walk together with us on this road [to political reform]. We have to admit that we now enjoy more freedom. The media, for example, is much freer than before. We couldn’t even dream of such freedom in the past. These are changes we can’t deny, but that doesn’t mean that those changes are complete.

What I am concerned about now is whether these initial changes will be able to continue to grow. We now have basic rights to form and run associations, organize activities, and so on. But if these rights can’t grow and develop, they will be like bonsai trees in a living room—just for show.

There are traps and obstacles that we have to overcome. There are still restrictive laws in force, such as the draconian Electronics Act, under which we were given 60-year prison sentences for sending out four emails—that’s 15 years for each email. Those laws are still instruments that they can use to throw you into jail anytime they choose.

You said earlier that you are not satisfied with the current political reforms. What kind of political transition would satisfy you?

Let’s talk about what should be done in this situation. One of the most critical issues in our country is the ethnic problem. Unless that issue is tackled seriously and immediately, any political reform will be a sham, and we won’t be able to build up a new nation. If we really want to continue this political reform, we need to solve the ethnic issue right away.

Min Ko Naing speaks at a public event a few months after his release from prison in January 2012.“I

—President U Thein Sein, speaking at the Royal Institute of International Affairs during a visit to London

“They slapped our faces and shouted out, ‘Shout like a man! Sound like a man!’”

—Myat Noe, a member of the famous gay dance troupe Moe Gyo Hngat Ngae, describing how he was abused by police in Mandalay following his arrest on charges of “disturbing the public”

“Last year I

—US-Asean Business Council President Alexander Feldman, on the growing number of places in Myanmar where foreign visitors can now use credit cards

“Sixty million people falling out of the sky–you’re not going to see that again in our generation.”

—Rita Nguyen, founder of Squar, a social network designed specifically for Myanmar users

had to carry a big wad of cash with me.”

guarantee to you that by the end of this year there will be no prisoners of conscience in Myanmar.”

More than US $3 million has been earmarked to restore the tomb of a former Siamese king and build a Thai cultural village

Homes Burned in Latest Outbreak of Religious Violence

near Mandalay, according to a source close to the project. Thai experts have been visiting Amarapura Township in Mandalay

previous clashes between Buddhists and Muslims since last year, order was quickly restored after this latest outbreak of communal violence.

Region since February to verify whether a stupa there was the tomb of Uthumphon, a Siamese king who had abdicated and was taken to the area after Hsinbyushin, the third king of Myanmar’s Konbaung dynasty, invaded Ayutthaya in 1767. “According to historical records and our findings, we, both Myanmar and Thai experts, can now say the tomb belongs to Uthumphon,” Mickey Heart, who has been granted full authority on the project by the Uthumara Memorial Foundation, a section of the Association of Siamese Architects, told reporters on June 29.

The family of Lo Hsing Han, one of Myanmar’s most notorious drug lords, announced his death at the age of 80 on July 7. Dubbed the “Godfather of Heroin” by the US government, Lo Hsing Han first got involved in the drug trade in the 1960s. In 1973, he was arrested in northern Thailand and later handed over to the Myanmar government. His initial sentence of death was commuted to life in prison, but in 1980, he was released as part of a general amnesty. In the 1990s, he and his son Stephen Law founded the conglomerate Asia World. Both father and son were put on the US financial sanctions list in 2008 for allegedly helping prop up Myanmar’s brutal former military junta through illegal business dealings.

A house burns in the background as a man carries makeshift weapons during communal clashes in Rakhine State in June 2012.

Two homes were destroyed by fire and three people were injured when a riot broke out in the coastal town of Thandwe in Rakhine State on the evening of June 30. The incident occurred after about 50 people gathered outside a police station after hearing a woman had been raped by “a man of another religion,” government spokesman Ye Htut said on his Facebook page. The rioters set two homes on fire at about 7 pm after police asked the crowd to disperse, and three Muslims were reportedly injured. Unlike

Authorities from Myanmar, China, Laos and Thailand seized more than US $400 million worth of drugs in a two-month operation targeting crime along the Mekong River, Chinese officials announced on July 2. From late April to late June, the four countries shared intelligence and hunted for drug lords and fugitives, resulting in the detention of 2,534 suspects and the seizure of almost 10 tons of drugs and more than $3.6 million in drug-related assets, the officials said. The joint patrols began in late 2011 after 13 Chinese sailors were murdered on the river. China executed the accused ringleader, Myanmar national Naw Kham, in March.

The United States imposed sanctions on a Myanmar general who it says violated a UN Security Council ban on buying military goods from North Korea despite Myanmar’s assurances it had severed such ties. LtGen Thein Htay is the head of the Directorate of Defense Industries, which the United States designated for sanctions a year ago, saying the organization has carried out missile research and development and used North Korean experts. The latest US action does not target Myanmar’s government, the US Treasury said after the new sanctions were imposed on July 2.

Lower House Passes Controversial Publishing Bill

Myanmar’s Lower House of Parliament approved a controversial Printers and Publishers Registration bill put forward by the country’s Ministry of Information on July 4, with few amendments to draft legislation that press advocates have decried as an affront to free speech. According to the bill the Ministry of Information would maintain the authority to issue publication licenses as well as to revoke or terminate those licenses if the holders violate the rules proposed in the bill. In addition, publishers can be brought to court and fined US $300 to $10,000 for offenses that include “disturbing the rule of law” and “inciting unrest,” provisions that critics say are too vague and ripe for abuse.

Myanmar’s government tightened security at the country’s main Buddhist sites, including Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, the Maha Myat Muni Pagoda in Mandalay and the historical temple complex of Bagan, following a series of bomb blasts on July 7 at Bodh Gaya in northern India, one of Buddhism’s holiest sites. Around 70 armed police were sent to guard the entrances to the upper terrace surrounding Shwedagon, according to the pagoda’s trustees. The security measures were taken after a series of bomb blasts injured two people at Bodh Gaya, a Unesco World heritage site in India’s Bihar State, where the Buddha is believed to have gained enlightenment. Some Indian media reports claim that the attacks were

conducted by radical Muslim groups seeking to avenge violence committed against Muslims by Myanmar Buddhists.

Armed policemen guard the eastern entrance to the upper terrace of Shwedagon Pagoda following blasts at Bodh Gaya, a sacred Buddhist site in India.

Myanmar’s government signed an agreement with the United Wa State Army (UWSA), the country’s largest and best-equipped ethnic armed group, on July 12 in an effort to defuse recent tensions in Shan State. Since late June, when the

UWSA rejected demands from Myanmar’s army that it abandon some of its positions, the two sides have reportedly been on the verge of open conflict. State media reported that the agreement includes clauses calling for prompt meetings between the two armies whenever military issues arise and committing the UWSA not to secede. The Wa, who once served as a major fighting force for the now defunct Communist Party of Burma, reached a peace agreement with Myanmar’s former military regime in 1989.

Well-known Myanmar singer Soe Tay was injured and his wife was killed in a crash on the Yangon-Mandalay Highway on July 14. Staterun newspaper The New Light of Myanmar reported that the accident happened

Britain’s Ministry of Defense extended an offer to restore military ties with Myanmar during a threeday visit to the United Kingdom by President U Thein Sein that ended on July 17. “The focus of our defense engagement will be on developing democratic accountability in a modern armed forces,” said British Defense Secretary Philip Hammond. U Thein Sein, who was the first Myanmar head of state to visit the UK in more than 25 years, had earlier declared that a nationwide ceasefire was possible within weeks, and that “the guns will go silent everywhere in Myanmar for the first time in more than 60 years.”

Critics said both the UK government’s offer and the president’s pronouncement

were premature, given the instability of existing ceasefire agreements.

near Meikhtila in Mandalay Region when their vehicle, driven by Ko Than Win Hlaing, 32, blew a tire, skidded out of control, crashed through a fence and then fell 5 meters. Soe Tay, 23, was sent to Mandalay Hospital to receive treatment for lifethreatening head injuries. His wife Ma Chaw Chaw, 22, died before reaching the hospital. The driver and another passenger, Ma Sabel Mon, 18, sustained minor injuries.

Myanmar’s government announced on July 14 that a special border guard force operating along the Bangladeshi border has been abolished. The force, known as Nasaka, comprised army and police officers and customs and immigration department officials. A brief announcement on the website of the President’s Office gave no explanation for the move. However, U Zaw Aye Maung, the minister for Rakhine ethnic affairs, said the Nasaka was dismantled because the Rakhine Investigation Commission, a team tasked with investigating last year’s outbreaks of communal violence in Rakhine State, found that the border guard force had not effectively performed its duties. Rights groups also say that the Nasaka had a record of human rights violations against the Rohingya Muslim minority living in the northern part of the state.

British Prime Minister David Cameron, left, shakes hands with Myanmar President U Thein Sein in front of 10 Downing Street in London on July 15, 2013. Nasaka members stand outside the headquarters of the border guard force in Maungdaw Township, Rakhine State PHOTO: REUTERS PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDY

Unlike the proverbial “bats out of hell”, Myanmar’s bats seem to prefer the more serene precincts of temples. Here, thousands of the webbedwinged creatures can be seen ascending from Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, Myanmar’s most sacred Buddhist site. It’s a ritual that can be witnessed every evening just before dusk, when a dark streak spreads across the sky as the bats set out in search of food. It’s also a reminder that in Myanmar, the human world— both sacred and profane—is never very far removed from that of nature.

It was 25 years ago that students led a massive uprising against military rule in Myanmar—an event that has shaped an entire generation and affected virtually every person in the country. After 26 years of disastrous decline under the regime of Gen Ne Win, the people of Myanmar had had enough. Little did they know then, when victory had seemed so near, that it would be nearly the same number of years again before they would finally begin to see the end of the long, dark night of oppression.

By AUNG ZAW

By AUNG ZAW

As a student at that time, I can clearly remember the exhilaration of knowing that the entire nation was behind us, that we could not possibly lose. But we were wrong. Though people came out into the streets in their millions all over the country, the military would not stand down. Too accustomed to holding power, and believing that only they could lead the way out of the crisis that they had created, the generals gave the order: shoot, shoot to kill.

And so thousands of young lives were mown down, and with them, the hopes of an entire nation. Some fled to the jungle to take up arms or seek allies abroad, while others went underground to defy the new regime from within. For more than two decades, an undeclared war continued to rage—a war on students, on the very people who had refused to lose faith in their country’s future.

They knocked on doors in the middle of the night: the military intelligence agents who didn’t care about the sobbing parents as they dragged their children away with hoods over their heads. They tortured and imprisoned any who dared to speak out against the regime. And when they couldn’t throw everyone who opposed them behind bars, the generals locked the gates to the universities, knowing they were breeding grounds for dangerous ideas, such as democracy and human rights.

Of course, students were not the only victims of the violence, which also targeted ethnic minorities and opposition politicians and affected everybody from poor farmers to rich businesspeople who fell afoul of the allpowerful generals. But it was students who were treated with the greatest

The 1988 uprising against military rule was not just about overthrowing a hated dictatorship: it was also about ending the reign of ignorance and brutality

distrust, because the weapons they wielded were their own minds, which refused to be yield to force.

Later, the junta refined its strategy for dealing with students: while keeping most campuses closed, it created new ones, banishing students to the distant outskirts of cities. Thus the prisons, home to some of Myanmar’s best minds, became in some ways the country’s most important centers of learning, while the universities, deprived of decent facilities and properly qualified instructors, became little more than holding centers for a dispossessed generation.

Now all of this has changed, or so we would like to believe. Students are no longer vilified in the staterun press, and most of Myanmar’s political prisoners have been freed. Some of the ’88 activists are now politicians, media people or artists, all determined in their own way to keep their struggle for democracy alive. Those forced to flee have begun to return, looking for ways to help rebuild the country they never really left behind.

There is some hope in the air in Myanmar today, but it is nothing like that of 1988. Then, it was possible to believe that the country could easily return to the days when, before the coup of 1962, it was seen as the most promising in the region. Now, there is half a century of rubble to remove before rebuilding can even begin.

But perhaps it isn’t necessary to clear away every remnant of the recent past, as we tried to do in 1988. Perhaps as we reclaim the space that was taken away from us and learn again how to speak openly, without fear of our overlords, we can, in the process,

dismantle the legacy of military rule.

Does anybody really believe that the former generals who now rule Myanmar understand the meaning of democracy? Probably not. But perhaps it doesn’t really matter, as long as we

are all determined to make what use we can of the little freedom we now have to create a nation based on respect for the rights of its people, rather than on dread of its despotic rulers.

This does not mean that we can forget the past, especially when its effects are still very much with us. Those who sacrificed their lives must be remembered, not only by their loved ones, but by the nation as a whole. But this can only happen in a country with real leadership. Until Myanmar has leaders who can acknowledge the past, the road to a better future will be strewn with obstacles.

These days, the way forward looks particularly daunting. Despite numerous ceasefires, conflicts in the country’s north remain unresolved because of the current government’s refusal to accommodate the desire of ethnic minorities for greater self-determination. Meanwhile, religious riots—evidently backed by some still in power today—are hurting the country’s efforts to rejoin the international community after decades of isolation.

Myanmar won’t be able to recover from its long years of abuse at the hands of its rulers on its own. It would truly be a tragedy—and a betrayal of the spirit of 1988—if agents of hatred and intolerance succeeded in robbing the people of Myanmar of the respect they have earned in the eyes of the world for their tireless struggle for democracy. Only by continuing to resist the forces of ignorance and brutality will we be able to win the war on students, and on the minds of all Myanmar citizens.

Aung Zaw is the founding editor in chief of the Irrawaddy. PHOTO: ALAIN EVRARD Myanmar’s 1988 student-led pro-democracy uprising brought millions of people into the streets all over the country.FOR MORE THAN TWO DECADES, AN UNDECLARED WAR CONTINUED TO RAGE—A WAR ON STUDENTS, ON THE VERY PEOPLE WHO HAD REFUSED TO LOSE FAITH IN THEIR COUNTRY’S FUTURE.

After years of ethnic conflict, people in eastern Myanmar’s border regions now have a new worry: recently restarted dam projects on the Thanlwin River

By SAW

By SAW

On May 22, representatives of the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT), accompanied by a team of researchers and students from Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University, traveled to the remote northern Thai village of Ban Mae Sam Laep in Mae Hong Son Province to meet with local residents and discuss plans to build a dam on the Salween River.

Ban Mae Sam Laep lies on the eastern bank of the Salween, a river that separates this corner of Thailand from Myanmar, where it is known as the Thanlwin. On the other side of the river from the village is Papun District, in northern Kayin State, an area with a long history of conflict between Myanmar’s armed forces and the Karen National Union (KNU), an ethnic Kayin armed group. These days, however, an uneasy peace prevails in eastern Myanmar, where the government has reached a series of tentative ceasefire agreements with ethnic Kayin, Kayah and Shan rebels.

Although it is still far from certain whether these truces will hold (in Shan State, clashes continue despite pledges to hold the peace), this hasn’t stopped a push to restart longstalled hydropower dam projects on the Thanlwin.

Altogether, six dams are planned for the river. Two—the Tasang and Upper Thanlwin dams—are located in Shan State, while the Ywa Thit dam is in Kayah State and the Wei Gyi, Dagwin and Hat Gyi dams are in Kayin State. Hat Gyi is the dam nearest Ban Mae Sam Laep.

Watsan Namchaitosaporn, the village’s deputy headman, seemed resigned to the fact that the US $1 billion, 1,200-megawatt dam, to be built by EGAT and China’s state-owned Sinohydro Corporation, would soon wipe Ban Mae Sam Laep off the map. “We don’t like it, but there’s nothing we can do about it. They’re going to build it anyway,” he said.

He explained that the visitors from Bangkok had informed him that even if the Thai side decided not to get involved in the project, the Myanmar government would go ahead with it, with Chinese help. “They [EGAT] don’t want to lose this chance. So we told them that the authorities have to find a new relocation site for us and provide us with proper compensation.”

According to surveys conducted by EGAT, the Hat Gyi dam will force six villages to relocate, while another 13 will be affected in some way. However, independent research by the Thailand-based NGO Karen Rivers Watch puts the number of villages that will need to be moved at 21. Forty-one other communities will also be impacted, the group says, bringing the total affected population to around 30,000 people.

The Hat Gyi dam was first approved by Myanmar’s Ministry of Electric Power in 2006, but until February of this year, when Deputy Minister of Electric Power U Myint Zaw told the Lower House of Parliament about plans to go forward with the Thanlwin dams, it was unclear if the government was still committed to the projects.

Already, even before construction work has begun in earnest, local people are feeling the impact of renewed interest in the dams. According to Steve Thompson, an environmental educator and researcher with the Karen Environmental and Social Action Network (KESAN), some people living around Hat Gyi have already been displaced, and there has been an influx of Myanmar government troops into the area to “secure” it for the dam project.

There is, in fact, a very real risk that pushing ahead with the dams could reignite conflict in the region. The Hat Gyi dam has long been opposed by the KNU’s Brigade 5, which controls territory near the dam site. But clashes in the area in April involved another group, the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA), which said it came under attack by a joint force of Myanmar troops and a Kayin Border Guard Force under Myanmar military command

when it refused to abandon one of its bases near the dam site.

That incident—which according to DKBA sources claimed more than 40 lives—shows just how fragile the peace is in this part of Myanmar, where insurgent armies have waged a decadesold campaign for greater autonomy. The foreign partners in the project are also painfully aware of this reality: In 2007, one Thai EGAT employee was killed and several others injured when unknown assailants attacked a workers camp at the dam construction site.

Nevertheless, a historic ceasefire agreement between the KNU and the government reached in January 2012 has convinced many decision-makers that the time is right to resume work on the dam, despite local opposition.

According to Mr. Thompson, the Hat Gyi dam appears to have created a serious dilemma for the KNU. “Local communities are strongly opposed to

A resident of Ban Mae Sam Laep catch fishes on the Thanlwin River.

A resident of Ban Mae Sam Laep catch fishes on the Thanlwin River.

the dam project, but it doesn’t appear that the current KNU leadership is taking their concerns seriously,” he said.

Mr. Thompson suggested that the KNU leaders may be allowing the project to go ahead, despite its negative impacts, because it believes it is “in the interests of what they see as peace and development.”

In other areas, civil society groups say that the ceasefire agreements have not made it any easier to assess the potential impact of the Thanlwin dams.

Khu Mi Reh, a spokesperson for the Karenni Civil Societies Network, a community-based organization that monitors the peace process between the government and the Karenni National Progressive Party, an ethnic Kayah armed group, said that his organization has been denied permission to inspect the site of the Ywa Thit dam in Kayah State, despite an agreement to allow independent assessments.

“We tried to travel to the dam site after the ceasefire agreement, but they [the government army] didn’t allow us to go the area where the dam will be built,” he said, adding that the heavy presence of government troops in the area has already forced many local villagers to leave.

Like the Hat Gyi dam, the Ywa Thit dam will be built by a Chinese company, the state-owned Datang Corporation, which signed an agreement with the Myanmar government in January 2010

to build three dams in Kayah State, including the 600-megawatt Ywa Thit on the Thanlwin River, and two others on the Pawn and Thabet rivers.

“We are worried about the social and environmental impact,” said Khu Mi Reh, citing concerns about the existence of a fault line near the dam site. “If an earthquake occurred, it could be devastating for people living downstream.”

This issue came up in late May, when more than 150 representatives from 40 different ethnic Kayin community organizations gathered to discuss the peace process. In a statement, they called on the KNU to speak to the public whenever they want to sign big business deals, such as for power plants and dams, which might damage the livelihoods of local civilians.

Naw Susanna Hla Hla Soe, the

Driving much of this anxiety is the lack of transparency surrounding many of these dam projects, despite the end of military rule in Myanmar and the cessation of conflict in many parts of the country. Increasingly, ethnic communities are questioning the way that the government and the leaders of ethnic armed groups are making deals without disclosing the details to the public.

director of the Yangon-based Karen Women’s Action Group, said that some projects, such as the dam on the Thaut Yin Ka River in Taungoo District, Bago Region, have already seriously damaged local communities.

“We only find out about the projects after they’re already having a negative impact on civilians. We don’t want such incidents to happen in the future,” she said.

Above left: A Buddhist monk leads local people of various religious backgrounds in a prayer to stop the building of dams on the Thanlwin River.

Above right: Boats line up along the bank of the Thanlwin at Ban Mae Sam Laep, one of the villages that will be flooded by the proposed dams.

Above left: A Buddhist monk leads local people of various religious backgrounds in a prayer to stop the building of dams on the Thanlwin River.

Above right: Boats line up along the bank of the Thanlwin at Ban Mae Sam Laep, one of the villages that will be flooded by the proposed dams.

“LOCAL COMMUNITIES ARE STRONGLY OPPOSED TO THE DAM PROJECT. IT DOESN’T APPEAR THAT THE CURRENT KNU LEADERSHIP IS TAKING THEIR CONCERNS SERIOUSLY.”

One word—tourism—glows on the horizon of hope for Sri Lanka. It is reflected in the surfeit of reportage and advertisements in the local press, where the talk of new city hotels in the capital and planned boutique hotels in exotic, tropical settings dominate.

This sentiment is understandable given the manner the South Asian nation is being promoted by the trendsetters for globe trotters. “Lonely Planet,” the bible of backpackers, rewarded the island with a glowing tribute, declaring it the Number 1 destination for its low-budget flock for 2013. Travelers on the other end, the well-heeled jet-setters, have been encouraged likewise by the up-market press. Such globally renowned glossies as Conde Nast and National Geographic and broadsheets like the New York Times have ranked the country among the top five tourism hotspots over the past three years.

That these words are being heeded is evident in the steady rise in tourist arrivals. Last year saw a record one million holidaymakers fly in to explore a country that had, till May 2009, endured a nearly 30-year-long civil war, pitting government troops against the Tamil Tiger armed separatists.

The military victory for the government, following a brutal final phase, has resulted in vast stretches of the country hitherto closed for the tourist trade opening up. So, in addition to visiting the country’s

historic Sinhalese kingdoms, its mistcovered mountains where tea is grown, and beaches along the southwest coast, foreign guests have a longer list to choose from. Visitors can now watch dolphins and whales (including the prized blue), go surfing and snorkeling, and explore game reserves famed for their wild elephants and leopards.

Yet it appears that the reported US $1.3 billion tourism brought to the national coffers from showcasing the country’s cultural and natural wealth is not enough for the government. The administration of President Mahinda Rajapaksa wants to tap another rich vein to rake in what some analysts here say could earn the country close to $1 billion annually: Indians with deep pockets and a taste for gambling, who are being eyed as the main draw for the planned expansion of casino tables in the capital. Colombo, the argument goes, will be a shorter distance, a more convenient location and a more culturally familiar setting for these high rollers from the subcontinent than Singapore or Macau, where many now fly to for some high-stakes fun.

A marquee venture, consequently, is enjoying a blaze of publicity. In the spotlight is Australian casino mogul James Packer, whose renowned Crown Group has been given a “sweetheart deal” of up to 10 tax breaks to build a 36-storey entertainment complex in the Sri Lankan capital. The stake in the estimated US $350 million venture, to house a 430-room hotel and

a sprawling casino, will be shared by Packer (45 percent), his local partner Ravi Wijeratne (45 percent) and a still undisclosed Singapore-based body. Construction is due to start in November and the casino is expected to open its doors in 2016, the year the Sri Lankan government has targeted to see its in-bound tourism traffic hit 2.5 million arrivals.

The “Crown Complex,” as it is now being promoted, will be located on the banks of Colombo’s most storied body of water—the Beira Lake. The contours of the country’s colonial and post-colonial economy are still visible around the lake.

store Sri Lanka’s

Warehouses thatfamous export, tea, are located here. And now a casino strip is on the cards as a sign of the new direction the postwar economy is taking. In addition to Crown’s latest money spinner, Colombo’s already existing, albeit smaller, gaming establishments are to be relocated to an area that punters here call the “Colombo casino zone.” Among these eight, which have been around for over two decades, are a cluster owned by Mr. Wijeratne, Mr. Packer’s partner and a veteran in the trade. Casinos with names such as Marina Colombo, Stardust or Ballys have thrived on a flow of South Asian, East Asian and local punters.

But now the promise of a jackpot economy is heading into troubled waters. Hardly impressed by this new turn in the tourism industry are respected members of the clergy in this predominantly Theravada Buddhist country. “It is not for the public good,” warned Venerable Udugama Sri Buddharakkitha Thera, the chief monk of the Asgiriya Buddhist order, Sri Lanka’s preeminent network of priests. “Foreigners don’t come here to go to casinos. We are completely against this.”

His verbal salvo broadcast on television has put the government on notice. “I have no political affiliations, but if this business is started, we will take to the streets against whoever supports it, be it government, ministers, parliamentarians or anybody else,” he asserted. “We will take to the streets against them all.”

Even an influential ally of Mr. Rajapaksa’s governing coalition in the Parliament has echoed similar concerns during a debate in the legislature. Sri Lanka does not need casinos to promote tourism given the country’s natural and cultural heritage, argued Patali Champika Ranawaka, general secretary of the Jathika Hela Urumaya, a political party led by Buddhist monks. Casinos, the minister for technology, research and atomic energy reminded the government, “goes against the state religion of Buddhism.”

A challenge to the casino trade has also been posed by the Bodu Bala Sena (Buddhist Power Force), which has, till now, been generating newspaper headlines for campaigns led by its monks targeting the country’s Muslim and Christian minorities. It was against “all (gambling) entities, not just Packer,” a spokesman told the media.

They are views that cannot be taken lightly, given the political role Buddhist monks have played in Sri Lankan democracy since the country gained independence from the British in 1948. The weight of the clergy was pivotal during 1956 general elections, which saw a party the monks endorsed win. The voice of the clergy also shaped government policy during the threedecade-long conflict—they often supported tougher measures against the Tamil Tiger rebels and groups sympathetic to the Tamil minority cause. Such an overt role is rooted in the country’s history, where Buddhist monks were recognized for their

political role as advisers to Sinhalese kings of the past.

The recent religious opposition is, in fact, a rare challenge to Mr. Rajapaksa, whose credentials as a political hero for the majority Sinhalese and a defender of Buddhism have rarely been challenged since he was first elected to power in 2005. And to limit the political fallout—yet keep the Packer casino venture on track—ministers have been rolled out to calm the religious waters by offering an innovative twist. The government “would not issue any new licenses to operate casinos,” Minister of Economic Development Lakshman Yapa Abeywardane told the Daily News, a mouthpiece for the state. The casino at Packer’s Crown Complex would be integrated into an already existing, licensed gaming house owned by Mr. Wijeratne.

This Buddhist opposition, consequently, has generated a values debate in some quarters. “It has been argued that the licensing of gaming resorts would serve to corrupt the morals of the Sri Lankan people,” stated the Pathfinder Foundation, a think tank, in a commentary published in The Island, an independently owned English-language daily. “This is difficult to sustain given the multitude of gambling centers [for horse races run overseas], legal and illicit, that already exist in every nook and corner of urban and rural Sri Lanka.”

It is a discussion with precedents. The last time was when the country’s 2002 tourism master plan was unveiled and there were moves to rid Colombo of its 24-hour casinos located in popular shopping neighborhoods. There was a lobby to create a “Casino City” in Bentota, a popular beach front along the country’s southwestern coast.

“This time it is different, because of the large foreign investment involving Packer,” says a Sri Lankan punter, speaking on condition of anonymity. “The government will have to strike a balance, and it seems to be saying the right thing for now.”

Moderate Buddhist voices with an eye on the economy are calling for more understanding by pointing to the easy co-existence that continues at the All Ceylon Buddhist Congress, one of the country’s oldest and most respected Buddhist organizations. Its recent presidents, they say, hail from a family that continues to make its fortunes from bookmaking.

YANGON — When Myanmar’s former dictator fell ill six years ago, he didn’t waste time looking for help at local hospitals. Instead, Snr-Gen Than Shwe got on an airplane and flew overseas to Singapore General Hospital, where he reportedly received treatment for an intestinal ailment.

It’s a vastly different story for U Haronbi, a 41-year-old laborer from Yangon who makes just 5,000 kyat (US $5.30) a day. He never set foot inside a hospital for the first four decades of his life, opting to treat himself with overthe-counter medicines during times of poor health. “I cannot afford much,” he told The Irrawaddy.

In 2007, the same year the now retired U Than Shwe sought treatment in Singapore, Myanmar’s former military junta spent less than $1 per person on health care, according to statistics from the Health Ministry. Six years later under the country’s new quasi-civilian government, experts are calling for an overhaul of a medical system that many say is broken after decades of underfunding.

The Health Ministry says it aims for universal coverage in the next 20 years—a major goal considering its starved budget—but in the meantime, patients in the government’s public hospitals have been forced to foot the bill. Yangon General Hospital, among Myanmar’s biggest and best known, is notorious in this regard, requiring patients to pay for any equipment used during their treatment. And in a country where the average person earns about

$2.50 a day, many are forced to forego care, or seek other options.

“For [Myanmar’s] public hospitals, which are completely under-resourced by the government, patients often have to pay for everything themselves—IVs, medications, dressings, cleaning, food,” said Dr. Vit Suwanvanichkij, a public health researcher who has worked with migrants from Myanmar on the Thai border for more than a decade, and who visited hospitals in Myanmar last year.

“It’s probably the most privatized health system in the world,” he added, noting that due to widespread poverty, particularly in rural areas, this means that the vast majority of Myanmar’s population is effectively deprived of any access to health care.

Official statistics also show that the government plays an almost negligible role in providing health care. According to National Accounts Data from the Ministry of Health in 2008-09, the ministry was responsible for just 10 percent of all health-care spending, while private households accounted for about 85 percent, with additional funding from other ministries and NGOs.

In Myanmar’s biggest city, there are a few other options for patients with limited income, including the Muslim Free Hospital, where Haronbi went earlier this year for a hernia operation.

In addition to offering free medical care to the city’s poor, the hospital has another draw: Its head surgeon, Dr. Tin

Myo Win, is the personal physician of opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

The hernia operation would cost about $100 at a public hospital, according to the doctor. “Here it’s charity, true charity,” he said of the hospital, which is named for the religion of its founders but is nonsectarian, serving people of all faiths and classes.

Several patients in the hospital’s surgical and outpatient wings said they avoided public hospitals because they could not afford them and had heard stories about poor treatment. “Some of the doctors and nurses are unfriendly,” said 19-year-old Ma Su Hla Phyu, a mother in Yangon seeking prenatal care during her second pregnancy.

U Ne Win, 53, preparing to be discharged after a surgery in May, agreed: “I’ve never been to any other hospital because I only trust this hospital,” he said.

Funding for the Muslim Free Hospital initially came through religious donations from local Muslims in the city, but later, largely thanks to Dr. Tin Myo Win’s relationship to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, donations also started coming from abroad.

Even so, the hospital has limited resources. The surgical unit offers just 25 beds—at least theoretically. “Sometimes we have to put [patients] in between the beds, so we can accommodate more than 35 or 40 if necessary,” Dr. Tin Myo Win said, adding that he often performs 10 to 15 surgeries in a single day. “You should only perform about

five major operations a day as a surgeon. Sometimes I have to stay late into the evening.

“This is a small hospital. Some cases, like heart operations, brain operations and kidney operations, we cannot afford to do them here,” said Dr. Tin Myo Win, who refers about two patients a week to other institutions, although they often say they cannot afford to go elsewhere.

Free medical services are also available at the Thukha Charity Clinic, a project of the Free Funeral Service Society, where pro bono care is offered by volunteer doctors and specialists, including orthopedic surgeons, oncologists, dermatologists, radiologists, pediatricians and ophthalmologists.

In rural areas, these services and more are covered by midwives, who are responsible for about 3,000 patients each in some states, according to the Health Ministry.

“They’re expected to do everything— primary health care, ante and postnatal care, pediatrics, delivering babies, collecting health data. Rural health-care providers joke that the midwife does everything except have the baby,” said Dr. Suwanvanichkij.

“They are so incredibly busy, underappreciated and underpaid for the essential services they are tasked with providing,” he added.

The reason for this overreliance on midwives is that doctors are in

extremely short supply. Availability varies from about six doctors per 100,000 people in Mon State to about 60 doctors for the same population in Chin State, according to Health Ministry statistics from 2009, the latest publicly available.

The lack of health infrastructure in rural regions has had devastating results. Malaria is a leading cause of death in Myanmar, while the country’s tuberculosis prevalence is more than 500 cases per 100,000 people, compared to about 270 cases on average regionally, according to 2010 data from the World Health Organization. For HIV, the prevalence is 455 cases per 100,000 people, compared to the regional average of 189.

The game is completely different for the limited strata of Myanmar’s population with wealth—including President U Thein Sein, who reportedly underwent a health examination at Singapore’s Mount Elizabeth Hospital last year.

Increasingly, Myanmar’s affluent are flocking to Bangkok, which is home to one of Southeast Asia’s most acclaimed hospitals, Bumrungrad International. More than 1,000 Myanmar patients travel to the hospital every month, including government officials and high-profile public figures, according to Daw Helen Hla Kae Khine Aye, senior manager of the hospital’s referral office in Yangon. That’s up

from about 50-60 Myanmar patients monthly when she started working for Bumrungrad a decade ago.

“In Myanmar, at our hospitals and medical care centers, maybe they couldn’t get the correct diagnosis,” she said. “A lot of people go abroad to get the correct diagnosis.”

Bumrungrad International Hospital has 14 Myanmar-language interpreters, and the referral office in Yangon helps patients arrange Thai visas and buy plane tickets in advance.

“There are two types of patients,” Daw Helen Hla Kae Khine Aye said. The first, “the very wealthy ones,” visit regularly for checkups and minor ailments. “The other type, they can’t afford much but they would like to get the correct treatment. They sell their houses and property just to go there.”

As Myanmar transitions from nearly half a century of military rule, health experts are calling for an overhaul of the country’s health system, though they admit the challenges will be immense.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who has made health and education reform two of her major platforms since winning a seat in Parliament last year, is spearheading a project to upgrade Yangon General Hospital.

Dr. Tin Myo Win, a member of the project’s fund-raising committee, said Parliament had already allocated 5 billion kyat ($5.3 million) to upgrade the century-old 1,500-bed hospital, including plans to build a new 1,000bed facility to accommodate patients during the renovation.

The surgeon is also developing a national health policy for Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy party, with a National Health Network that he formed this year. In addition to meeting health experts from Myanmar and overseas, the network plans to create a mobile clinic with surgeons, specialists and emergency medical technicians traveling to remote areas.

Starting this year, some public hospitals have also begun offering limited financial aid—but they’re not advertising it.

Yangon’s North Okkalapa General Hospital began offering financial aid in January for patients who could not

afford to pay for their medicine or IVs, according to an assistant medical officer at the Muslim Free Hospital who completed a yearlong internship at North Okkalapa General Hospital last year.

“But the patients don’t know about it,” said the medical officer, 23-year-old Sandy, who studied at the University of Medicine (2) in Yangon. “The public hospital in Insein Township also started offering financial aid, but patients from Insein still come here [to the Muslim Free Hospital] because they do not know.”

Meanwhile, the Health Ministry’s goal of achieving universal health coverage within 20 years will be very difficult to achieve with a health budget that Dr. Tin Myo Win calls “very insufficient.”

“For the Ministry of Health, we can understand. With the amount they have in their hands, they are doing quite a good job for the people,” said the doctor. “But how can you [fix everything] with this limited budget?”

According to the latest figures, health-care spending still accounts for only about 3 percent of the total national budget.

Other experts say it is important to keep a broad focus, with attention paid to building reliable data systems and ensuring that investment reaches rural areas.

“There are so many moving parts that are broken,” said Dr. Suwanvanichkij. “I think when it comes to public health, you need to work on all these places to fix up this messed up Rubik’s Cube.”

nonsectarian charity hospital that offers free health The Rubik’s Cube“THIS IS A SMALL HOSPITAL. SOME CASES, LIKE HEART OPERATIONS, BRAIN OPERATIONS AND KIDNEY OPERATIONS, WE CANNOT AFFORD TO DO THEM HERE.”—Dr. Tin Myo Win of the Muslim Free Hospital in Yangon

We are afraid of China,” said President’s Office Minister U Aung Min last November during a public meeting in Monywa, central Myanmar, where local people had been protesting a controversial Chinesebacked copper mine. U Aung Min, who once fought hard against the Beijingbacked Communist Party of Burma, told protesters demanding a complete shutdown of the Letpadaung mining project that, “We don’t dare to have a row with China!”

“If they feel annoyed with the shutdown of their projects and resume their support to the communists, the economy in border areas would backslide,” he added. “So you better think seriously.”

Of course, any serious observer would agree that no matter who is running the country, Myanmar must be sensitive (the word “afraid” is not politically savvy) to its northeastern neighbor. However, the minister’s statement drew outrage from the activists and general public. In newsweeklies and on social media websites such as Facebook, people went wild with comments, labeling the Chinese as exploitive and the Myanmar government as betraying the nation’s interests, with U Aung Min bearing the brunt of antiChina sentiment.

Despite the official rhetoric by both countries about China and Myanmar’s unique paukphaw (fraternal) relationship, a large number of Myanmars do not seem to regard China as a compassionate brother. In the sibling hierarchy, China enjoys the role of the paternalistic older brother, and Myanmar of the younger.

In the wake of the 1988 prodemocracy popular uprising, and after the subsequent military takeover, Myanmar relied on China for political, economic and military support—with profound internal and international ramifications. In a domestic context, the public became increasingly intolerant of Chinese migrants who had settled in the country or come for employment after the military takeover. The population of Chinese descent currently living in Myanmar is estimated to be between 3 million and 5 million.

Lacking longitudinal data or independent surveys about popular attitudes toward the Chinese in Myanmar, it is worthwhile to study the topic through contemporary cultural and media works, including poems, books, short stories, magazine and newspaper articles, cartoons and jokes which went through the former junta’s heavy censorship.

Military memoirs are also revealing. After reading about a dozen memoirs published recently by former generals, it is fair to conclude that the military regarded the Chinese with mistrust. The memoirs describe the military’s hardfought battles from the late 1960s to the late 1980s against Myanmar’s banned Communist Party, which received massive Chinese support, as a struggle against foreign invasion via a proxy.

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the societal figures of Myanmar were mostly proChinese because left-leaning writers dominated public discourse. The first notable anti-Chinese expression came in the aftermath of 1988, with a collection of seven short stories known as “ Wathoundare Let-ye ” (“Handwriting of the Earth’s Guardian Spirit,”), which were published in 1989. Written by famous novelists in the mid- and late-1980s, all seven stories covered the changing community and cultural landscape in Upper Myanmar as new Chinese migrants replaced native residents with massive real estate purchases and dominated businesses.

The collection of stories captured a sense of dread among local Myanmars for the disintegration of their social fabric. Written under heavy censorship, the stories did not explicitly include the word “Chinese” but implied the characters’ ethnicity by describing their heavy accents, fair or yellowish skin, a certain style of clothing and a poor understanding of the Myanmar language. The characters also referred to themselves with the personal pronoun Wa, commonly used by the Chinese in Myanmar.

In the early 1990s, some business magazines featured articles about newly thriving Sino-Myanmar border trade, real estate markets and changing socio-economic conditions.

The most significant writings that persistently focused on Chinese encroachment in Upper Myanmar came from the influential writer Ludu Daw Amar, a former heroine of the country’s independence struggle. In a famous article series called “ Amay Shay Sagaa ” (“Mother’s Old Sayings”), Daw Amar said Myanmar’s societal disintegration and cultural decline had been caused by several factors, including

poverty, the distorted market economy, and the “superhumans” (military generals and their children) and lawpan (rich Chinese businessmen). She denounced the rise of lawpan khit, or an era of rich Chinese businessmen, in Myanmar society, while urging the public to resist their domination and decadence.

Some short story writers circumvented government censorship to portray the losing battle of local Myanmars against Chinese money and “cultural intrusion” in the 1990s. One of the most popular stories, “Kara-oke Nya-chan” (“Karaoke Evening”) by Mandalay writer Win Sithu, was about the moat of Mandalay’s Royal Palace—a source of Myanmar cultural pride that symbolizes the country’s last kingdom and independence—and how it became the site of a karaoke bar. In the story, female singers at the bar serenade Chinese customers with Chinese songs, and a drunk man vomits into the moat.

In the mid-2000s, writer Hsu Hnget described Mandalay’s changing culture in the following passage: “Virtually no shops and workplaces are closed for religious holidays, even for the full moon day [of Buddhist Lent]. Except in one case: Chinese New Year! During the Chinese New Year, nothing can be sold and bought. Everything is stopped, silenced, and the roads are clear.”

Writers have creatively invoked traditional proverbs, songs, images and other relevant symbols to bypass censorship and convey their messages. For instance, Nyi Pu Lay wrote a short story about a Chinese intrusion in Myanmar for Shwe Amyutay magazine in March 2011. The story’s title, “Taei-ei A-naut Mha ” (“Slowly Moving Westward”), was inspired by a wellknown Myanmar tabaun prophetic saying, “ Tayote ka pi shan ga ei shi thi bama a-naut mha .” (“When the Chinese press down, the Shans lean on the Burmans. The Burmans are then forced to move westward”).

Authors have not been the only ones expressing concern about Chinese influence in Myanmar. Comedians have also had their say, including in the popular short play “Mandalay-tha-sitsit-gyi Ba Bya!”(“I am a Real Mandalay Resident!”), a one-act performance by a famous comedian group from Mandalay in 2009. The main character in the play calls himself a native Mandalay resident, but his style and accent have changed because he lives among a growing

Chinese community and has been forced to assimilate. He explains his experience by citing a Myanmar proverb: “Mi mya mi naing ye mya ye naing” (“If fire is in force, fire prevails, and if water is in force, water prevails”).

Recently, anti-Chinese rhetoric has become increasingly loud and intense with public outrage over the Chinesebacked Myitsone dam project and the Letpadaung copper mine. In nearly every conceivable medium, critics have called to save the Ayeyarwady River and the Letpadaung mountains, as millions of people depend on them for their livelihoods. Some writers have railed against “Chinese exploitation” and the Myanmar military’s collaboration, with many works invoking a thematic line from the national anthem: “This [Myanmar] is our nation, this is our land, and we own it.”

Public criticism has been emboldened by the government’s decision to lift prior censorship in August 2012. In the case of the Letpadaung mine, harsh words have been cast not only at Minister U Aung Min, whose comment about fearing China drew particular backlash, but also at democracy icon Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who chaired the investigation committee that recommended continuation of the mining project.

The Myitsone dam and Letpadaung mine controversies have elevated antiChina attitudes to their highest levels in Myanmar since 1969, when riots against the Chinese broke out. After U Aung Min’s comment in November, sources close to Chinese officials told me that some Chinese policy makers believed he

had intended to provoke anti-Chinese sentiment. When I met U Aung Min early this year and asked him about the allegation, he slowly but rhythmically shook his head. “No, no,” he whispered.

All in all, the confluence of growing anti-Chinese sentiment amid Myanmar’s ongoing political transition could be a cause for serious concern. In the early phase of democratization, a mix of widespread poverty, fear among key stakeholders of losing financial and political power, increasing levels of free speech, and weak government institutions could allow for the emergence of populism and nationalistic violence, possibly in the form of antiChinese riots.

Anti-Chinese populism should be tempered and constrained by all parties concerned. Otherwise, Beijing could feel threatened and react with more visible interference in Myanmar, hoping to protect its vested interests. If that happened, Myanmar’s state-building efforts and much-needed development would be severely undermined.

Min Zin is pursuing a PhD in political science at the University of California, Berkeley. This article is based on his paper “Burmese Attitude toward Chinese: Portrayal of the Chinese in Contemporary Cultural and Media Works,” published in the Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs in 2012.

Though it happened more than two decades ago, U Win Kyu is still haunted by old memories. Daw Khin Htay Win, his wife, is torn between her wish and her husband’s promise to their daughter.

His mind drifts back to a September evening 25 years ago. He was running from ward to ward in Yangon General Hospital looking for his daughter after learning that she was in critical condition after being shot by the army. Around him, the hospital was teeming with patients badly injured by triggerhappy soldiers. He recalls that there were pools of blood on the floors.

“Every year at this time, it all comes back to me,” said the 61-year-old father, recounting the last hours of his daughter Ma Win Maw Oo, who moaned in pain on the hospital bed suffering from a fatal wound caused by a bullet that shred a lung.

The 16-year-old schoolgirl was gunned down in downtown Yangon with other pro-democracy demonstrators on Sept. 19, 1988—the day after a new junta seized power after months of protests. Her fatal shooting was captured in a photograph that shows her blood-soaked body being carried away by two young doctors. That image, which appeared in the Oct. 3, 1988, issue of Newsweek’s Asian edition, soon became an icon of the brutality of the crackdown.

Every year in September when the anniversary of their eldest daughter’s death is approaching, the couple in their sixties faces a great dilemma: should they perform Buddhist rites to release Ma Win Maw Oo’s soul into the afterlife, or fulfill the wish she expressed to her father from her deathbed? Her dying words were, “Don’t call my name to bestow merit upon my soul until Myanmar enjoys democracy.”

The parents of a girl who was killed by Myanmar’s army in 1988 say their daughter will only rest in peace when real democracy is restored

The eighth-standard girl’s final wish is a shocking one in Myanmar society, where a deeply rooted traditional belief has it that a person’s soul can’t rest in peace until his or her name is called out by the family to share their merit with the deceased.

“As a mother, I don’t want her soul to wander,” Daw Khin Htay Win said with a deep sigh. “But I have to respect her wish and my husband’s promise to her,” she added, explaining why the family hasn’t shared their merit with their daughter for the last 24 years.

Despite Myanmar’s recent democratic reforms, the family said they still don’t feel that they can call for merit to be bestowed upon their daughter’s soul this year.

“You cannot say democracy is now flourishing in our country,” U Win Kyu

told The Irrawaddy recently, sitting in front of an enlarged picture of his daughter in the family’s one-room shack on the outskirts of Yangon.

“As long as we don’t have a president heartily elected by the people, we cannot call her name to bestow merit upon her soul,” he said. His wife nodded in agreement.

Both parents remember Ma Win Maw Oo as a “good” daughter who supplemented the family income by selling sugar-cane and traditional snacks in the streets. She wanted to be a singer inspired by the Myanmar pop star Hay Mar Ne Win (not related to then dictator Gen Ne Win). She hated injustice, so when the country’s people rose up against military rule in 1988, she knew she had to join.

“It was her burning sense of [the

government’s] injustice that took her life,” said Daw Khin Htay Win.

Min Ko Naing, the most prominent student leader of the 1988 uprising, said that Ma Win Maw Oo and others who gave their lives for the cause of democracy did not do so in vain.

“If possible, I wish I could tell her we are still marching to the goal she wants by crossing the bridge she and other people built by sacrificing their lives,” he said.

Since Ma Win Maw Oo’s death, her family has had an extreme dislike of the army. But, as time goes by, their hatred towards Myanmar’s military men diminishes. U Win Kyu said he prefers to let bygones be bygones, and is not interested in seeking justice for his daughter.

“My daughter was brutally killed and I myself also used to have bitter feelings towards the army,” he said. “But now I’ve come to realize that it

was her destiny to face that kind of death. We no longer hold a grudge.”

But they still want something.

“We want the president to make some sort of memorial to honor those who fell during the ‘88 uprising,” said Daw Khin Htay Win, adding that that would be the best way to assuage the grief of families who lost loved ones in the struggle to restore democracy.

“If it really happened, it would fill us with pride and joy,” she said.

In 1988, Myanmar hosted some of the largest demonstrations in recorded history. These began officially on Aug. 8, the supposedly auspicious “8/8/88” in a country run by “retired” generals, numerologists and soothsayers. Although Myanmar’s political volcano had been rumbling for at least a year, the world was still caught unawares by the sudden tumult in a country that had essentially been forgotten. Foreign press access was minimal. The story then got knocked off the world’s top slot when the C-130 Hercules carrying Pakistan’s president, Gen Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, mysteriously fell out of the sky on Aug. 17.

The failed 8/8/88 rebellion lasted nearly six weeks. It followed 26 years of bizarre and xenophobic misrule by strongman Gen Ne Win. Late that year, when there was still some lingering hope of change, an old Asia hand predicted it would take at least as long to put right the damage the old general had wrought. As we look back from 25 years on, that prediction has turned out to be grimly true. A quarter century down the road, can any lessons be learned from the failures of Myanmar’s pro-democracy movement in 1988?

The large early demonstrations in Yangon, a city of well over three million at the time, mobilized virtually the entire populace of the capital. Although Myanmar was not a country with large

population centers, there were similar scenes in smaller cities, including the northern capital of Mandalay with a population of over 800,000. Given the terrible communications and transport infrastructure, the size of these protests was all the more remarkable. Indeed,

one of the worst individual incidents of bloodshed followed a demonstration around a police station in Sagaing near Mandalay, a lightly populated area famous for its mist-shrouded hilltop temples.

In the second half of August and

the first half of September, Yangon continued to see large, well-organized marches on a daily basis. Students, workers, civil servants, nurses, monks, nuns, schoolchildren, secret policemen, air force personnel—just about everybody who could gather behind a

banner and march the streets did so, airing well justified grievances. After decades of locked-down frustration, the demonstrations were initially cathartic but of diminishing marginal value. Towards the end, there was some violence that included the beheading

Opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi in her study at home in late September 1988. In an interview with Asiaweek magazine on Sept. 25, 1988, she said, “A lifetime in politics does not appeal to me, but how long is a lifetime? Obviously, once you start a movement like this, you don’t stop halfway and say, ‘That’s it, I’ve had enough.’ You just stay there until it reaches a logical conclusion of some kind.”

of up to 50 vagrants, possibly the work of provocateurs. There was also some looting. With such huge, largely peaceful turnouts, however, it was inconceivable that calls for meaningful change could be ignored—but they were.

Myanmar’s economy was moribund, there was widespread unemployment and education led nowhere. Everything from fuel to rice was in short supply, and anything manufactured, be it an aspirin or instant coffee, had to be obtained on the black market. The most resourcerich country in Southeast Asia was an economic and social shambles. It had humiliatingly been compelled to apply for “least developed country” status with the United Nations to receive aid.

When everybody has so much reason to complain, one of the biggest challenges becomes the triage of issues: finding the overlaps among all the problems that must be addressed most urgently and to best effect. In Myanmar’s case, the situation was made even more complicated by over a dozen low-intensity ethnic insurgencies which had continued to deny the central government in Yangon control of any of its frontier areas.

Thanks largely to Gen Ne Win, the military had a dismal track record on reform and utter contempt for technocrats and educated people in general. The emerging opposition was meanwhile inchoate and, not surprisingly, completely inexperienced in government. In the event, the brutal military backlash on Sept. 18 which installed the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) of Snr-Gen Saw Maung ensured nothing was really tackled beyond the immediate unrest. The military simply hunkered back down, again ignored critical opinion at home and abroad, and heaped blame on anyone but themselves.

Within days of 8/8/88, the protests had at least achieved the removal of “Butcher” Sein Lwin, the man who replaced Gen Ne Win at the end of July as head of the ruling Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP) and who also became president. Gen Sein Lwin was followed by a more conciliatory interim figure, Dr. Maung Maung, a lawyer and academic who had also served as Gen Ne Win’s hagiographer.

Although many consider this was a cynical play for time by the Ne Win clique intended to allow troublesome poppies to grow tall, Dr. Maung Maung at least talked of democratic reforms

and staging multi-party elections. But so had Gen Ne Win when he ostensibly stepped aside. Dr. Maung Maung lifted martial law, and there was a window of a month while the demonstrations carried on. A credible, unified opposition failed to emerge despite much talk of forming an interim government. There was also a call in early September for Dr. Maung Maung to step aside. Given Myanmar’s modern history and the Ne Win government’s intolerance of any organized structure, even the Buddhist Sangha, the failure of the opposition to come up with a viable alternative was to be expected.

Myanmar’s pro-democracy icon Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was then a

Ko Naing, the “Conqueror of Kings”, but they could not find a suitable umbrella figure or movement to lock in behind and get to the next level.

All these players were certainly well aware of the dangers of a fragmented opposition, but still failed to somehow link up and accommodate each other in a bigger frame. In early September, it was U Nu, the prime minister ousted by Gen Ne Win in 1962, who sensed something had to be done and made a move. He reassembled the remnants of his old cabinet and declared himself to still be Myanmar’s legitimate premier. Although this made him popular with some workers and students, it alarmed the military and caught other

political neophyte who only appeared after the August uprising was under way. Moving from a standing start, she had her father’s great name but no personal experience or political machine to back her. Indeed, her National League for Democracy (NLD) was only formed after SLORC’s coup. Brig-Gen Aung Gyi, whose critical letters to Gen Ne Win had stirred public discontent, was the NLD’s first chairman. However, he still saw some value in the military and soon split off with his own party.

Workers had sufficient awareness to mobilize a general strike but not to take matters beyond that. Students were the core agitators and organizers, with inspirational leaders such as Min

opposition figures off guard, including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, Brig-Gen Aung Gyi and Gen Tin Oo—who was actually in U Nu’s party at the time.

A man who had always muddled his devout Buddhism with politics, U Nu was traumatized by the violence surrounding SLORC’s appearance. He later admitted to being impetuous, but his real error may have been doing the right thing the wrong way. U Nu continued to reconvene his cabinet in a garden room at his home, even though many of his ministers were long dead and attended in spirit only, literally.

In late September the junta, to its rare credit, endorsed the five-man election commission created by Dr. Maung Maung. Over 400 parties applied

for registration in the following months. This staggering number was rightly reduced to about a dozen eligible for participation, of which only the NLD and the National Unity Party (NUP), which replaced the BSPP, really counted. With Daw Aung San Suu Kyi under house arrest, the NLD under the leadership of a cashiered colonel, U Kyi Maung, effectively countered the fragmentation problem and won a landslide election victory in May 1990, trouncing the NUP. This free and fair election was subsequently ignored by the military. It was clear evidence of how hopelessly the generals continued to misjudge the mood of the people, but amply demonstrated the value of calm focus. By 1990, people had come to realize

that the paramount issue was getting a competent government in place, and that all other matters must follow from there.

One of the great myths propagated by the West and its media is that democracy produces better governments. In recent decades, one need look no further than Australia, Cambodia, Egypt, Greece, Iran, Italy, Thailand, the UK, the US or Venezuela to see that perfectly free and fair elections can produce perfectly rotten governments—which is exactly why elections are so valuable. The great

gift of democracy is not the guarantee of electing a better government; it is the power it gives the electorate to vote out a bad one in a peaceful, orderly manner. The Catch 22, however, is that a bad government will often not allow itself to be dismissed in a decent

and transparent process. Indeed, SLORC’s disinclination to honor the 1990 election result is one of the best examples of this.