Where Are the Former Military Strongmen?

WWII Memories: Last of the Old Soldiers

Japanese Models Dominate Car Market

Growing Grapes in the Golden Land

FEATURE:

SEA GAMES: A TURNING POINT?

BUSINESS: TELECOMS SET FOR A TAKE-OFF FOOD: A FLAVOR OF INDIA

Where Are the Former Military Strongmen?

WWII Memories: Last of the Old Soldiers

Japanese Models Dominate Car Market

Growing Grapes in the Golden Land

FEATURE:

SEA GAMES: A TURNING POINT?

BUSINESS: TELECOMS SET FOR A TAKE-OFF FOOD: A FLAVOR OF INDIA

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Aung Zaw

MANAGER : Win Thu

The Irrawaddy magazine has covered Myanmar, its neighbors and Southeast Asia since 1993.

EDITOR (English Edition): Kyaw Zwa Moe

ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Sandy Barron

COPY DESK: Neil Lawrence, Paul Vrieze, Samantha Michaels, Andrew D. Kaspar, Simon Lewis

CONTRIBUTORS to this issue: Aung Zaw; Myat Thu Aung; Marwaan Macan-Markar; Lawi Weng; Samantha Michaels; Simon Lewis; Simon Roughneen; Saw Yan Naing; Yan Pai; Kyaw Hsu Mon; Virginia Henderson; William Boot.

PHOTOGRAPHERS : JPaing; Steve Tickner

LAYOUT DESIGNER: Banjong Banriankit

REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS MAILING ADDRESS: The Irrawaddy, P.O. Box 242, CMU Post Office, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

YANGON BUREAU : No. 197, 2nd Floor, 32nd Street (Upper Block), Pabedan Township, Yangon, Myanmar. TEL: 01 388521, 01 389762

EMAIL: editors@irrawaddy.org

SALES&ADVERTISING: advertising@irrawaddy.org

SUBSCRIPTIONS: subscriptions@irrawaddy.org

PRINTER: Chotana Printing (Chiang Mai, Thailand)

PUBLISHER LICENSE : 13215047701213

18 | Intelligence: Where are Myanmar’s Strongmen?

Out of sight, but not out of mind, life goes on for the leaders of the country’s hated old regime

22 | Feature: Going for Gold

Could the SEA Games revitalize Myanmar sport?

28 | Profile: Last of the Old Soldiers

Nearly seven decades have passed, but David Daniels is still haunted by memories of his days as a British soldier in WWII

30 | Feature: Myanmar’s Unloved Flag

From the opaque way it was chosen to the muddled messages it sends, Myanmar’s national flag is an unwelcome reminder of the former junta’s decades of misrule

32 | COVER Death in the Forest

A deadly trade is steadily decimating Myanmar’s wild elephant populations

38 | Telecoms: End of the Drought

More big telecoms firms could still enter what remains a pristine market

42 | Automobiles: As Car Market Expands, Japanese Models Rule

Strong demand has fueled a boom in automobile imports, with Japanese vehicles leading the way

46 | Roundup: Electricity Shortage Grows to 5,000 Megawatts

For decades, there was no love lost between the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and Myanmar’s military regime. As an organization funded by the US Congress and tasked with promoting democracy across the globe, the NED earned the junta’s ire by funding exiled Myanmar dissidents and ethnic minority causes opposed to the former ruling generals’ authoritarian rule.

Now, after more than two-and-a-half years of democratic reforms under President U Thein Sein, the once icy relationship appears to be thawing. In October, an NED delegation led by its president, Carl Gershman, visited the country to meet with civil society leaders and government officials in Naypyitaw and Yangon. The Irrawaddy’s founder Aung Zaw sat down with Mr. Gershman at the tail end of that trip to talk about the ongoing reform process, the challenges of democratic transition, and his meetings with men who once considered him the enemy.

it’s very difficult for the United States to have a friendly relationship with a dictatorship. I remember when Chile was under the rule of [Augusto] Pinochet, the relations were extremely difficult and unfriendly. Once Chile had a democratic election, it was night and day. Relations changed and we had a friendly relationship.

I could see that relations could be very difficult if the process moves backward. That could really complicate things.

Some critics say power and wealth in Myanmar are still controlled by the same people who have governed—brutally and undemocratically—for decades. What do you say to those who feel that justice has not yet been served?

This was your first trip to Myanmar. What were your impressions?

I think a process has been started that’s going to be very difficult to turn back. I met a lot of people in both civil society and independent media, as well as in the government, and everybody wants to at least show that they’re committed to this process. Everybody says they’re for democracy. Admittedly, it’s the beginning of what will be a long and difficult process, but there are many things I saw that give me hope.

I had a meeting with about 40 young people, mostly women, mostly from minority groups. They’re hungry to understand democracy. There’s more hunger to understand and work for democracy here than in the United States today, where we tend to take it for granted. Among the government officials, they want someone like me to endorse what they’re trying to do, and

as long as they stay on the right path, that’s fine with me.

I know transition is very difficult, but I remain hopeful because one of the things that has happened here is that the system has opened up and people like The Irrawaddy are back here. You’re opening up political space and when you open up political space, people get educated, people’s expectations grow.

As we say often, the genie is out of the bottle. You can’t put it back in. That’s the nature of democracy.

How do you see the MyanmarAmerica relationship evolving?

One of the leaders I met with complained about the past and felt that the sanctions the United States imposed on Burma were a terrible mistake—that a policy of engagement would have been much better. I explained that

Certain things are easier to achieve than others. It’s very easy to have an opening, maybe negotiate an agreement on constitutional or electoral reform. Those things can happen quickly. But just as in 1989 when communist governments fell, going from there to changing a system that grew up over decades is very difficult.

You’ve raised the issue of transitional justice. It’s something you’re going to have to work out. That’s not going away. In some countries, like Russia, they’ve done nothing on that. And the crimes under Stalin were, frankly, much worse. And I don’t think Russia can become a democracy unless they deal with what happened in the gulag, where millions of people were killed. You cannot forget that.

In South Africa and Chile, they dealt with it through a truth and reconciliation process, without being punitive. Other countries deal with it differently.

Have you gotten a sense that there’s a political will to discuss this?

It may be too early. I don’t know. The people who are really committed to

human rights, they want justice now. But that means you’re going to have problems with some of the people that were responsible for the crimes of the past. It’s not going to be easy, but you can look at other national experiences as to how that can be done in a way that makes a distinction between those who were part of the system and people who really were responsible for crimes.

Is it a good thing that the West is engaging with the military?

I think if it’s the right kind of training, yes. For them to understand what the proper, modern relationship is between a military and society, where the military doesn’t rule over the society but protects the nation, and what makes a professional military. To have programs on that, I think that’s all positive.

Given its track record, do you really think Myanmar’s military can be taught to respect human rights and democracy?

They’ve now committed themselves to that. Do I think they’ll actually do it? I don’t know, but I do believe that having them commit to that is important, because then you have a standard that you can hold them to.

When our country was founded, we had in the Declaration [of Independence], “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” Well, that wasn’t true. We had slavery and fought a civil war over that. Then we had 100 years of inequality and Martin Luther King, Jr. said those words were a promissory note—that this is what’s owed to the people, and that’s what the whole civil rights movement was based on. Having a commitment to these things, getting those words into the Constitution, into law, gives the people a legal legitimacy and a basis on which to carry out a struggle.

One of the leaders that I met was concerned about the gap between expectations and reality. Yes, there is a gap, and that gap is going to continue

to exist. And if they don’t measure up to those expectations, there are going to be continued protests.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has said Myanmar’s Constitution is one of the world’s most difficult to amend. Are you optimistic that it can be done?

I’ve looked at the complexities of it and how difficult it will be to make changes to the Constitution. At the same time, it’s perfectly clear that this is not a democratic Constitution. And it’s a Constitution that is going to have to change. And you have people in

Just as the government will be divided, the opposition, too, will be divided. There is an inevitable tension between human rights and democratic transition. Ultimately, they have to go together. And I think it could be a creative tension. Hopefully, the people who are raising the issues of political prisoners, ethnic rights, religious extremism, and so forth, will help make the process of negotiation and compromise more accountable to the people.

I agree with you that the process underway can neutralize some of the

the government that are on different sides of this issue. That’s a good sign. Divisions within the ruling group are always helpful to democratic progress.

There has also been some criticism of the opposition since the reforms began. Daw Aung Suu Kyi, for example, has come under fire for her silence on the Rohingya issue and for being overly accommodating to business interests at the expense of landholders in the case of the

voices for ethnic rights, for human rights, and so forth, because [the government and the opposition] are trying to agree right now, and that makes it very difficult to raise sensitive issues. But clearly, there are going to be people who raise these sensitive and difficult issues and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is going to have to speak about these things.

Disclosure: The Irrawaddy is funded in part via a grant from the National Endowment for Democracy.

PHOTO: NED

PHOTO: NED

—Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, speaking to CNN, stated that she started in politics as the leader of a political party, not as a human rights defender or a humanitarian worker.

All Talk, No Action?

—Saw Luther Htoo, onetime child “leader” with his twin brother Saw Johnny Htoo of the God’s Army splinter group of the Karen National Union, now resettled in Sweden.

—U Khin Zaw Win, a former political prisoner who spent 11 years in jail, on claims by former prime minister and spymaster U Khin Nyunt that he was always “only following orders” in an interview with the Wall Street Journal.

“I’m always surprised when people speak as if I’ve just become a politician. I’ve been a politician all along.”

“I like Sweden… it’s very cold, but no-one’s shooting at each other.”

“I believe Khin Nyunt is talking rubbish, with a mind on his exoneration for his crimes.”

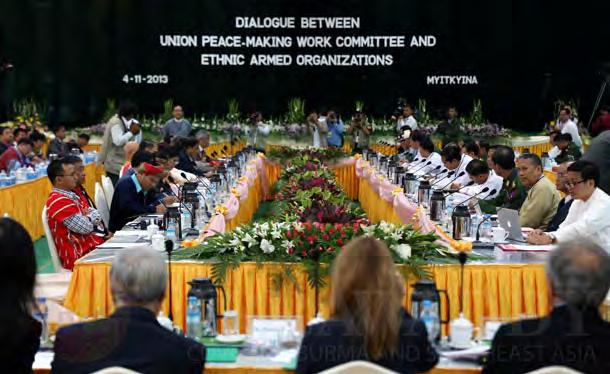

Representatives of most of Myanmar’s largest ethnic armed groups gathered in Mytikyina, capital of Kachin State, on Nov. 4-5 for the first round of multilateral talks with the cen-

tral government’s peace team. Days earlier, the ethnic rebels had concluded a meeting aimed at reaching a common position on the government’s proposed nation -

wide ceasefire agreement. All but one of the groups at that meeting, held in Laiza, the headquarters of the Kachin Independence Organization, agreed to accept the proposal if the government promised to begin a comprehensive political dialogue early next year. In Myitkyina, the two sides failed to achieve a major breakthrough, but agreed to meet again for further negotiations. One key sticking point was the government’s call for the ethnic militias to end their armed resistance, while the armed groups said they wanted to see the formation of a “federal army.”

amphetamine pills, as well as crystalline methamphetamine and precursor chemicals, “increased significantly in 2012.” Last year, the number of seized methamphetamine pills increased threefold to about 18 million pills, the biggest haul since 2009, while opium cultivation and production “reached their highest level since 2003,” the agency said. It was the sixth consecutive year that opium production rose in Myanmar, which now produces about 10 percent of the world’s opium, making it the second-biggest producer after Afghanistan. However, production levels remain far below those of the mid1990s.

to death days earlier. The latest outbreak of violence since communal clashes began more than a year ago prompted relief agency Médecins Sans Frontières to suspend some of its operations from the state over “misunderstandings” that have led to charges of bias in favor of Muslims.

Children displaced by violence in Pauktaw Township in 2012 wash themselves at an IDP camp.

An ethnic Rakhine woman was killed in an attack by three unidentified Muslim men in Pauktaw Township, Rakhine State, on Nov. 2, in the latest incident of violence between local Buddhist and Muslim communities in the state. The attack, which also left one other Rakhine woman severely injured, was allegedly in retaliation for the death of a Muslim man found beaten

Five men identified as Myanmar nationals were rescued by police in Malaysia on Nov. 5 after being held captive, allegedly by a compatriot, according to a report by The Star, a Malaysian daily. Police said the brother of one of the victims alerted them to the crime and later led them to a room at a resort in

Bukit Tinggi, Pahang State. “All of them were chained together and they claimed that they were fed only once a day,” said assistant police commissioner Abdul Rahim Abdullah, adding that the room was used by a Myanmar man who worked for the resort’s maintenance department. The man was arrested three hours later and faces the death penalty if found guilty under Malaysia’s 1961 Kidnapping Act.

Opium and methamphetamine production continues to rise in Myanmar, according to a report by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime. The report, released on Nov. 8, said seizures of opium, heroin and meth -

Australia’s government has decided to stop funding the Mae Tao Clinic in the Thai border town of Mae Sot from the end of this year. The clinic, which serves tens of thousands of impoverished Myanmar nationals every year, currently receives US $426,000 annually from the Australian government. Like other Western countries, Australia has shifted the focus of much of its aid to projects inside Myanmar as conflicts in border areas ease. However, the clinic’s founder, Dr. Cynthia Maung, winner of the 2013 Sydney Peace Prize, said, “In my time here I have never seen the

patient caseload decrease, and it won’t until there’s years and years of stability and security.”

Myanmar’s main opposition party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), said that it has overwhelming public support for its calls to amend Myanmar’s controversial 2008 Constitution. The party held large rallies in Yangon and Naypyitaw in November in a show of popular backing for its proposed changes to the militarydrafted charter, which critics decry as undemocratic. An unofficial poll conducted at the rally in Naypyitaw showed that 88 percent of the 25,000 people who attended supported amending the Constitution, while 8 percent thought it should

be scrapped completely. “Amending the Constitution is a must for peace, stability and the development of the country,” said NLD leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who is barred from becoming president under the current Constitution.

A Russian warship arrived at the Thilawa port outside Yangon on Nov. 13 to strengthen militaryto-military ties between Myanmar and Russia. Part of Russia’s Pacific fleet, the 163-meter Admiral Vinogradov, together with a tanker, the Irkut, and a tugboat, the Kalar, docked at the port until Nov. 18. The visit included a meeting between the ship’s crew and Myanmar Navy officers. The ship was also open to the public for two days.

According to a state media report, “The large antisubmarine warship Admiral Vinogradov is an Udaloyclass destroyer which has been in active service since 1988.” The visit coincided with the 65th anniversary of Myanmar-Russian diplomatic ties.

Seven protesting farmers were injured on Nov. 14 when police opened fire into a crowd at the controversial Chinese-backed Letpadaung

Former US President Bill Clinton and former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair visited Yangon in quick succession in November, highlighting growing international interest in Myanmar’s political and economic reforms. In a speech delivered at the Myanmar Peace Center on Nov. 14, Mr. Clinton emphasized the importance of resolving ethnic conflicts and increasing transparency in the resource sector. Less than 24 hours later, Mr. Blair addressed an audience at the same venue, echoing the sentiments of

the former US president. Both men sought to allude to Myanmar’s current situation by describing

possible parallels elsewhere, but for the most part did not discuss the country directly.

copper mine in Sagaing Region. The incident occurred when villagers were attempting to set up a protest camp to oppose the restarted project. An official account claimed that the villagers had attacked police with makeshift weapons, and that nine police had been injured in the clash. A week earlier, Buddhist monks had established a protest camp near the mine site, claiming that, contrary to a report in state media, a controlled explosion at the mine had damaged a nearby Buddhist pagoda. Police barricaded a road to prevent villagers reaching the monks’ camp, so about 30 farmers tried set up a new camp.

Sixty-nine political prisoners were released from 18 prisons around the country on Nov. 15, including two grandsons of the late Myanmar dictator Gen Ne Win. U Kyaw Ne Win and U Aye Ne Win were charged with high treason for plotting to overthrow Myanmar’s then ruling junta and given suspended death sentences in 2002, shortly after their grandfather Gen Ne Win died while under house arrest on Dec. 5, 2002. Also released were Naw Ohn Hla, a female activist who had organized protests against the Letpadaung copper mine in Sagaing Region, and nine activists in Rakhine State who had been imprisoned under Article 18 of the Peaceful Assembly Act for leading unauthorized protests against aid support plans for the Rohingya Muslim community.

Ethnic Kayin dancers wait their turn to perform during the Kayin State Day fair in Hpa-an, the state capital. Thousands flocked to the annual government-organized event, drawn by performances of traditional dancing and singing and the many amusement rides on offer. At the opening ceremony, messages of unity and peace were proclaimed in light of recent ceasefires between the government and the Karen National Union (KNU) and Democratic Karen Benevolent Army (DKBA). Among those in attendance were some sporting t-shirts emblazoned with the insignia of DKBA- or KNU-affiliated groups—a sign of changing times in a state long divided by conflict.

By AUNG ZAW

By AUNG ZAW

The opening of Myanmar will not be complete until peace and stability are achieved in ethnic regions. But as those who have been following the country’s long history of civil war know, that is still a distant and elusive dream.

Increasingly, however, political observers are not the only ones paying close attention to this issue. Jon Frederik Baksaas, CEO of Telenor— one of two telecom companies to win licenses to operate in Myanmar—was surely speaking for many other foreign investors when he said recently that the peace process was “very important” because tensions make working in “certain areas sensitive.”

But while businesses, both foreign and local, certainly have a legitimate interest in Myanmar’s unresolved conflicts, the growing trend in recent years to treat the peace process as if it were an industry in its own right should be a cause for concern.

Ever since he came to office in 2011, President U Thein Sein has prioritized peace in Myanmar’s ethnic regions, and this focus has brought with it millions of dollars in funding and technical support from abroad. Institutions from the EU, Norway, Switzerland, Sweden and Japan have all gotten involved in the government-led peace agenda, while opposition figures such as Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and several key leaders and civil society groups have been notably absent.

Much of the money now pouring into this process has gone to the Myanmar Peace Center, which was established with the president’s blessings in October 2012 to engage in “confidencebuilding” activities. What this has meant in practice is a proliferation of meetings among government ministers, ethnic delegations and “peace brokers” around the country. Many of these have been little more than photo ops, seemingly aimed at giving those in

attendance a chance to post amateurish propaganda on social media sites.

This lack of tangible progress on substantive issues might explain the growing urgency with which the president has been pushing for a dramatic breakthrough. During a visit to the UK in July, he told an audience at Chatham House, an influential British think tank, that nationwide ceasefire talks would be held “over the coming weeks” and boasted that “the guns will go silent everywhere in Myanmar for the first time in more than 60 years.” Five months later, we’re still waiting.

The closest we’ve come so far to a real turning point was in early November, when many of Myanmar’s ethnic armed groups met with a government delegation in the Kachin State capital Myitkyina. It was the first time that multilateral talks had been held, and came a few days after the ethnic militias gathered in Laiza, the headquarters of the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), to discuss their common stance for negotiations with the government.

The Myitkyina meeting ended in disappointment, however, when it became clear that the two sides still had fundamental differences on key issues.

A key demand of the government was for the ethnic armies to end their resistance, which many have continued for decades (although only one major group, the KIO, is still on a war footing with the government army since the collapse of a ceasefire in June 2011). In this, Naypyitaw was barely moving from the position of the former military junta, which had insisted in 2009 that the ethnic ceasefire groups disarm and form Border Guard Forces under the command of the Tatmadaw, or Myanmar armed forces—a demand that most rejected.

Myanmar still has 18 different armies, including major groups representing the Kayin, Kachin, Shan, Wa and Mon ethnic minorities. Each of these groups control parcels of territory of various sizes in the country’s border territories. It is estimated that ethnic insurgents have a combined total of about 100,000 fighting forces. Several ethnic leaders are also involved in lucrative businesses, including mining,

logging, border trade, taxation and, in some cases, illicit activities such as drug trafficking.

What these ethnic armies want is the formation of a federal army, one in which ethnic minorities are on a more equal footing with the Burman majority that now overwhelmingly dominates the Tatmadaw. But this is something the country’s current military leaders won’t accept.

In an interview with The Irrawaddy, Lt-Gen Myint Soe, the leader of the Armed Forces delegation to Myitkyina, said that the only armed forces Myanmar needed was the Union armed forces. But he also said that there was no immediate plan to forcibly disarm the ethnic armies. Rather, he said, the goal was to gradually integrate them into mainstream politics.

Although neither side got what it wanted from the Myitkyina meeting, the good news is that they agreed to continue speaking to each other. Before that, however, the ethnic armies plan to meet again in Hpa-an, capital of Kayin State, to sort out some of their own differences.

Meanwhile, as the peace process moves forward with greater Western involvement, another major foreign influence also needs to be considered: Myanmar’s powerful neighbor, China.

Beijing has long expressed a desire to see peace restored in Kachin State, where it has massive investments in the local jade trade, mineral exploration and hydroelectric power. It came as no surprise, then, that it sent observers to

the talks in Myitkyina.

At the same time, however, Beijing has actively supported Wa insurgents in Shan State, which also borders China. The United Wa State Army, which didn’t take part in the talks in Laiza or Myitkyina, was formed after the collapse of the Beijing-backed Communist Party of Burma in 1989, and is one of the most powerful armed groups in the country. According to a report last year by Jane’s Intelligence Review, it is also the recipient of large

war-torn Kachin State twice in just one year, becoming the first top US diplomat to travel to this sensitive area in several decades.

It is clear, then, that the West and China are beginning to exercise considerable influence over Myanmar’s still fragile peace process. Many remain skeptical, however, that foreign “peace experts” and other outsiders understand Myanmar’s complex ethnic and political divisions well enough to be of any real help in ending more than

quantities of military hardware from China, “including man-portable air defense systems [and] Chinese-made armored vehicles.”

What this reflects, perhaps, is Beijing’s concern that the West— and particularly the United States— is rapidly extending its presence in Myanmar right into China’s backyard. Signaling Washington’s keen interest in Myanmar’s ethnic conflicts, US Ambassador Derek Mitchell has visited

half a century of conflict.

Although there are no easy answers to how Myanmar can achieve a lasting peace, it is important for all parties to realize that simply throwing money at the problem—or looking at it solely through the lens of their own commercial or strategic interests—will only make matters worse.

Aung Zaw is the founding editor-inchief of The Irrawaddy. PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDY

THE IRRAWADDY

Until recently, the country’s khaki-clad leaders roamed the country, “inspected” state projects and offered instructions on how to build a “peaceful and modern nation.” But where are they now?

Ex-Snr-Gen Than Shwe and former Vice SnrGen Maung Aye now live in secluded compounds in Naypyitaw and Yangon. They receive regular visitors, including high-ranking military and government officials.

In November, as Myanmar marked the Kathein festival, the country’s richest tycoons, as well as politicians including President U Thein Sein and Union Parliament Speaker U Shwe Mann, paid their respects to ex-Snr-Gen Than Shwe. The former head of the regime is praised within the powerful military establishment as the man who formulated the road map for the transfer of power and a “bloodless transition.”

The former dictator, who is still very much regarded as Myanmar’s central authority figure by the generals and ex-generals now in power, is said to be “worried” about the country’s future, but passes his time at home largely by reading books.

Ex-Vice Snr-Gen Maung Aye, meanwhile, has suffered a stroke and is paralyzed. Informed sources say that the no-nonsense general, who was once based in

northern Shan State, has completely retired from politics and administering the armed forces. “He is in a wheelchair and is no longer interested in politics—he’s waiting for his day to come,” said a source close to the family of the former junta’s No. 2.

The general, who was a renowned whiskey drinker, is said to have stopped taking alcohol and to have become more religious. Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing, the current commander-in-chief, recently paid a visit to the retired general’s residence, where he held a Kathein ceremony and offered robes to Buddhist monks.

Former spy chief U Khin Nyunt, now free from house arrest after being purged from the regime, recently opened an art gallery in Yangon. The former general, long known as Myanmar’s “Prince of Evil” for his role in torturing dissidents following the crackdown on the 1988 pro-democracy uprising, showed up to his gallery’s opening in a white tunic, and is also reportedly funding the building of a pagoda. In a recent interview with the Wall Street Journal, he lamented that no one has sought his advice as a political strategist or consultant.

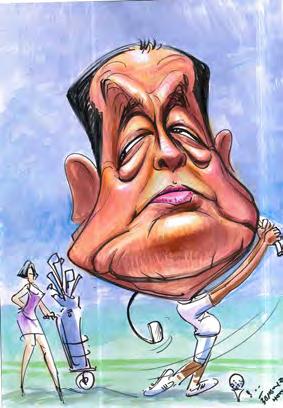

But what of U Tin Aung Myint Oo, the former vice president, who abruptly left his post with little explanation last year?

The formidable former general, who won several titles for bravery in the 1970s and went on to control the country’s powerful trade council (and who is considered to be one of the richest men in Myanmar), is no longer in the news.

U Tin Aung Myint Oo’s departure was put down to health reasons, and he was said to suffer from throat cancer. However, the general once dubbed a hardliner is often spotted on the golf courses of Yangon and appears to be in good health. The former general remains tight-lipped about why he left the post, but he is said to be unhappy with—and to have questioned the “sincerity” of—President U Thein Sein.

Aside from playing golf, he is said to be building a bell in the Ayeyarwady delta, in the manner of Myanmar’s former monarchs, who often made merit by building pagodas and bells and donating to religious institutions. U Tin Aung Myint Oo’s bell is reportedly going to overshadow the Mingun Bell in Sagaing Region, which weighs 199,999 pounds (90,718 kg). The buying up of vast amounts of bronze to make the bell is said to have driven up local prices of the metal.

Although they are absent from public life, it seems the ex-generals’ large egos remain intact.

As the new chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, there are many things Myanmar could do to have a lasting, positive impact

By KAVI CHONGKITTAVORN / BANGKOKAs the new chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), Myanmar has to face challenges emanating both from home and from the grouping’s agenda. How the chair handles these issues— both in terms of agenda-setting and narratives—will determine the status of Myanmar within the region and broader international community in the future.

Myanmar can draw best practices from Asean to maximize the benefit it derives from its long-awaited chairmanship, skipped in 2005. To see what is possible, it need only look at the example of Indonesia. Before it democratized in 1998, Indonesia represented the lowest denominator within the grouping. No Asean agreements or measures could move ahead without a nod from its largest member. Now, 15 years later, Indonesia has taken the lead in pushing for changes to bring Asean to new heights. Jakarta has successfully raised the grouping’s international profile and energized overall engagement with major powers. New ideas and frameworks proposed by Indonesia have already strengthened the rule-based organization to ensure compliance by its members.

Indonesia’s efforts have been possible because of the country’s

steady democratic development and openness—with vibrant media and civil society groups—as well as its willingness to discuss its own internal issues, something long considered taboo by Asean norms. During the East Timor crisis of 2000, for instance, Jakarta asked Asean to contribute to the formation of an international peacekeeping force. Thailand, the Philippines and Malaysia responded to the request as individual members. It was the first time that Asean had washed its dirty linen in public.

Similarly, Myanmar’s ethnic issues and its religious and communal conflicts are no longer hidden from outside scrutiny. Over the past two years, local and international media have reported directly from affected areas inside the country. Therefore, these problems feature high on the Asean agenda due to their repercussions on neighboring countries and Asean as a whole. But as the current chair, Naypyitaw could choose to suppress discussion of these issues, as one of the prerogatives of its new position is the power to determine the agendas of all Asean meetings from now until December 2014.

If the past is any indicator, the new chair may choose to avoid mentioning, much less discussing, these issues completely. However, it could also use this unique opportunity to address

them in constructive ways. For example, instead of shying away from the Rohingya refugee crisis, which has both domestic and regional dimensions, Myanmar could voluntarily report on it to its colleagues. It could also provide an update on the progress of the country’s national dialogue and reconciliation efforts with various ethnic minorities. At the Asean ministerial meeting in

Bandar Seri Begawan in July, Indonesia won praise for unilaterally reporting on its human rights situation. Thailand and the Philippines will do the same at the meeting next year.

By openly raising sensitive issues, the chair could establish new best practices in a way that would have

regional implications. Such updates and dialogues would help increase confidence among Asean members in their ability to discuss sensitive issues. While this wouldn’t necessarily lead to regional solutions to all problems, as there are still constraints on how Asean members can work together on certain issues, such courage would engender goodwill toward Myanmar and result in a better understanding of the country’s domestic dynamics.

In the past, the Asean chair has called for special meetings to deal with particular crises, such as outbreaks

two years. Democratic reforms and broader public and media participation in debates on national policy have had positive outcomes on Myanmar’s integration with the global community. Increased engagement between the Asean decision makers and civil society groups would raise the status of the new Asean chair.

Myanmar can become the region’s game changer due to the greater interests paid to Asean by major dialogue partners, including the US, China, Japan and India. These powers are wooing individual Asean members to join their spheres of influence. As the chair, Naypyitaw has to make sure that Asean stays united and focused. A divided Asean would weaken the grouping, which is something it cannot afford. Any discord at this juncture would undermine the grouping’s bargaining power in the global arena.

Besides domestic issues with regional implications, issues related to traditional and non-traditional security

of avian flu and SARS or the aftermath of Japan’s tsunami and nuclear dilemma. These actions normally came about when Asean faced a terrible crisis and wanted to respond collectively and quickly. But even in the absence of immediate threats, Myanmar could work toward enhancing interactions among Asean members in a way that would enable them to contemplate preventive and forward-looking measures.

Doing so would complement the substantive progress on economic and political reforms that have taken place inside Myanmar over the past

would also be high on the chair’s agenda. Nuclear non-proliferation is certainly one of them. After long-standing condemnation of its nuclear ambitions and its relations with North Korea over missile technology, Myanmar could come clean and subsequently inform Asean that it will lobby the nuclear powers (US, Russia, UK, France and China) to sign the Southeast Asian Nuclear Weapons Free Zone Treaty during its chairmanship. If Myanmar succeeded in doing this, its legacy as Asean chair would be a long-lasting and positive one.

Kavi Chongkittavorn is a Thai journalist.Myanmar’s ethnic issues and religious and communal conflicts are no longer hidden from scrutiny.Myanmar’s President U Thein Sein, left, raises the Asean gavel after receiving it from Brunei’s Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah during the closing ceremony of the 23rd Asean Summit in Bandar Seri Begawan in October 2013.

By SIMON ROUGHNEEN / NAYPYITAW

By SIMON ROUGHNEEN / NAYPYITAW

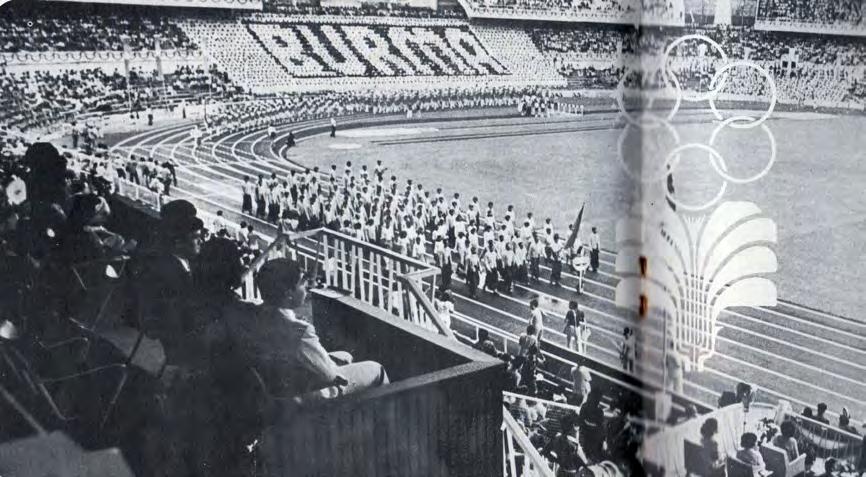

Yangon was once Southeast Asia’s aviation hub, prejunta Myanmar had probably the region’s best education system, and the country’s living standards were as good as those of any of its neighbors. All that changed, however, after a 1962 coup. Gen Ne Win’s search for the “Burmese Way to Socialism” led to Myanmar’s rapid economic decline, leaving it a moth-eaten economic outlier where nowadays only a quarter of the population has electricity.

That fall from grace was also mirrored in the country’s sporting performance. In the 1960s, Myanmar topped the SEA Games medal table twice, and as late as 1979, it managed a third place on the medal-winners ranking. For the most part, however, since the SEA Games were last held in Myanmar in 1969, the country has slipped into sporting oblivion, falling way behind neighbors such as Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines and, more recently, Vietnam, who all have done well at the SEA Games.

“The government didn’t support the people who play sports or assist talented young people to develop their sport abilities,” U Khin Maung Htwe, a long-time sports journalist in Yangon, told The Irrawaddy. “Our country had a good name in the past for sports, but during the military era, the government wanted us to be isolated.”

Myanmar’s total haul of SEA Games medals over the decades now stands at 1,858, putting it seventh overall, far behind leader Thailand’s 5,025 medals or second-placed Indonesia’s 4,410.

But history shows that the host country usually does well, often topping the medals tables or finishing in the top three—though the host’s haul is often abetted by some sharp pre-games arrangements, such as pushing for the inclusion of local sports that other countries are not familiar with.

Not wanting to break with history, it seems, Myanmar was itself accused by other countries of trying to gerrymander the event roster to suit itself. The allegations stung, and Dr. Myat Thura Soe, international relations secretary at the Myanmar National Olympic Committee, sought to counter barbs thrown at the host country from Thailand and the Philippines.

“We had a meeting between all the countries early in 2013 and we decided between us all then what sports to include,” he told The Irrawaddy, speaking at a hectic office in the interior of the Wunna Theikdi Stadium in Naypyitaw, a new 30,000-seat venue where the 2013 SEA Games track and field events will be held.

Despite Myanmar compromising with angry rivals on what sports to include, Dr. Myat Thura Soe is hopeful

that Myanmar can nonetheless do well at the SEA Games, though he conceded that competing with countries such as Thailand and Indonesia at the top of the medals board might be a step too far, for now at least.

What Myanmar’s sports officials hope for, however, is more long-term: that hosting the Games can jump-start the country’s sporting engine and help Myanmar move back towards the top of the Southeast Asian pile.

“We think of the example of Vietnam,” said Dr. Myat Thura Soe. “After they hosted the SEA Games, they went up to the top level in Southeast Asia.”

Vietnam hosted the SEA Games for the first time in 2003, topping the medals table that year with 183 golds, and since then has been a consistent top-three SEA Games finisher along with Indonesia and Thailand.

“In 2001, Myanmar and Vietnam were almost the same level, but now they have progressed way ahead of us,” said Dr. Myat Thura Soe.

Central to the country’s plans for enhanced sporting prowess in the years to come are the pristine new facilities in Naypyitaw, all specially built for the Games. The Wunna Theikdi Stadium is the centerpiece of a bigger complex that includes an Olympic-standard swimming pool and diving area, as well as an 11,000-seat indoor stadium for basketball and smaller facilities for various martial arts.

The SEA Games men’s football tournament, likely to be the main spectator draw at the Games, will be

“After Vietnam hosted the SEA Games, it went up to the top level in Southeast Asia.”

—Dr. Myat Thura Soe of the Myanmar National Olympic CommitteeSpanking new swimming facilities in Naypyitaw

staged a 30-minute drive away along desolate football-pitch-wide highways, in another 30,000-seat stadium on a hill between Naypyitaw’s military museum and the city’s zoo.

Many of the SEA Games facilities were built by Max Myanmar, the sprawling conglomerate headed by U Zaw Zaw, a tycoon long sanctioned by the United States for his ties to Myanmar’s old army regime. Max Myanmar was, however, ranked in the top 10 in a recent listing of the country’s taxpaying companies—a sign to some of a budding corporate transparency in a country long known for inscrutable business dealings.

“We started in 2010. At the time, it was all forest here,” said U Khin Maung Kywe, Max Myanmar’s construction director, speaking from the viewing area of the Wunna Theikdi Stadium, where President U Thein Sein will be joined by other regional heads of government for the SEA Games opening ceremony on Dec. 8.

But looking out over the stadium—a white and silver amphitheater baking in the sun—one had to wonder how this and other venues could be put to use once the Games are over.

Here and there in Naypyitaw, there are statues of white elephants, which according to Myanmar lore signify

that a just and powerful king sits on the throne. But will the lavish new sporting facilities in Naypyitaw really help Myanmar reclaim its former athletic glory, or will they turn out to be white elephants of a far less auspicious kind?

So far, the government is short on specifics about what it will do with the

new facilities, apart from hand them over to the Sports Ministry. But officials say they won’t repeat the mistakes of Laos, which as host of the 2009 SEA Games built new stadiums in the capital Vientiane, only to let them fall into disrepair after the Games were over.

Dr. Myat Thura Soe said that one option is to make Myanmar’s worldclass sporting venues available to foreign athletes. “Singapore has expressed an interest,” he said, noting that the citystate doesn’t have much space for big sports training grounds.

“This will help us in Myanmar, as we can have joint training with other athletes,” he said. “We want the SEA Games to be a boost for Myanmar’s sporting future.”

Charming and in radiant good health for an 87-year-old, David Daniels is testament to the benefits of discipline and prayer. A founding member of the Burma Star Association (soldiers who fought with the British during World War II), he is now one of the last remaining members of the British Burma forces.

Amy a simple wooden bungalow in North Yangon decorated with British royal portraits, group photos of his ancestors and religious memorabilia. His secret for robust longevity? “No drink, no smoke, lots of tea. But there were lots of drinks during the army days.”

Born and brought up in Mandalay, Mr. Daniels joined the forces in December 1941, aged not yet 17,

enlisting as a gunner in the Burma Auxiliary Force, part of the Royal British Legion in Burma, St George’s Hanover Branch. His father Reginald Daniels served in Palestine for the British Turks during WWI and was against his joining up. “But I was taken by the uniform and the marching and all. In the end he allowed me.”

Gunner David Daniels, serial number 3675, served in the 1st Coast Battery RA under Major W Jackson and in the Field Battery RA under Colonel Perrot. “During the war, I found that none could compete with the British, their discipline and their fighting. If they knew they would face certain sacrifice, they would retreat. They would not waste a life.”

The realities of war were a terrible experience. After 70 years, the nightmares are still with him.

“With the Japanese advancing, we retreated, crossed our bridge in Upper Burma and blew it up afterwards, destroying it on April 26, 1942. It was the last bridge before we went to India along with the Chinese troops. Half the people died on the way, of malaria and starvation,” he recalled. Mr. Daniels spent two months in hospital in Assam recovering from malaria and chronic dysentery.

Fierce fighting was experienced on the night of March 8, 1945, as the 4th Battalion of the Prince of Wales Gurkha Rifles climbed and finally captured Mandalay Hill. “A lot of

Left:

Below: A photo of Mr. Daniels in full uniform with his four medals, taken by Viscount Slim, president of the Burma Star Association, at the Htauk Kyant War Cemetery during a visit to Myanmar in 2008.

Previous page: Mr. Daniels relaxes at home with his wife Amy.

he attends the Anglican Cathedral service, then goes to the Htauk Kyant War Cemetery north of Yangon to meet some war colleagues. The British Embassy sends a car at 6:15 am to take him to the remembrance service. Afterwards he enjoys a drink and the Ambassador’s buffet. “Good refreshments at the British embassy!”

A clean liver and practicing Christian, Mr. Daniels catches the bus to worship on alternate Sundays at St. John’s Armenian Church and the Anglican Holy Trinity Cathedral, which has a Forces Chapel dedicated to the men and women of many races and religions who fell while fighting with British and Allied Forces during the Burma Campaign, 1942-1945. Shields on the walls represent crests of the regiments and groups who served in this country.

“After the war, I worked for three years in charge of nighttime telephone calls and receiving telexes at the French embassy. Then I joined International Testing Services, a British company checking the quality of cooking oil and beans. I also did government service auditing military accounts from 1946-1986 before retiring. President U Thein Sein increased my pension from 800 kyat a month to 45,000 kyat.”

Gurkhas were killed in the clearance between the pagodas. The chaps had no cover; they couldn’t reach safety. It was too high. I was below the hill firing 25-pounders. Captured men were tortured. It was better to be killed. Nowadays I wake shaking in the night. I have terrible dreams of people cutting off heads. I couldn’t find the remains. I was so frightened. I don’t mention all my suffering to my wife. But sometimes she hears me shouting in the night.” His wife’s familiar voice helps to soothe the devils in the dark.

For his service, Mr. Daniels was awarded the 1939-45 Medal, the Burma Star, the Defence Medal and the War Medal. On the Sunday closest to Nov. 11, Remembrance Day,

Proud of his service, Mr. Daniels has on his living room wall a handmade poster of his family tree covered with well-worn poppies. His maternal grandfather, a British soldier with the Daniels surname, fought in the Third Anglo-Burmese War (188586) under Maj-Gen Prendergast VC, when the British occupied Mandalay and sent King Thibaw and his wife Queen Supayalat into exile in India. “He married my grandmother Ma Ma Gyi who was a maid of honor attending the Queen in the Mandalay Palace. Sometimes I can’t get over it. How did my grandfather and grandmother speak?” A dozen more family members are honored in this humble, important document.

“When the British embassy car drops me back home, the driver asks me, ‘Same time next year?’ I say, ‘If there is no final roll call for me, I’ll come.’”

By THE IRRAWADDY

By THE IRRAWADDY

It’s been three years since it was first unfurled, but for many in Myanmar, the country’s new national flag remains an uninspiring sight. Few have any idea how or why it came to replace its predecessor, but most know that it is a legacy of the former military regime— and for that reason alone, it is regarded with a certain amount of scorn.

Much of the controversy relates to the manner in which the flag was adopted. First raised on Oct. 21, 2010, it was officially approved in May 2008,

in the same rigged referendum that supposedly garnered 93.8 percent support for the military-drafted Constitution. But its origins go back to November 2006, when the idea of changing the flag was first proposed.

It appears that it did not take long to settle on a new design. By Jan. 2, 2007, the state-run mouthpiece The New Light of Myanmar was able to quote some of the “intellectuals” and “intelligentsia” tasked with crafting the new flag on the reasons for their choices.

“The national brethren of Myanmar have been living in unity and amity. A big white star representing the love and unity of the Myanmar people should [therefore] be included in the State Flag,” said U Win Maung, one of the members of this group.

He went on to explain the choice of colors: “Green, representing agriculture that is the main business of the Union of Myanmar, which is peaceful, lush and verdant, should be portrayed. Yellow, which reflects the unity and amity of the national races, should be

Pre-Colonial Period: Founded by King Alaungpaya (1714-1760), the Konbaung Dynasty (1752-1885) was the last dynasty to rule Myanmar until it was defeated by the British.

Colonial Period: The British at first administered Myanmar as a part of India, but in 1937 it became a separate colony, with this as its official flag from February 1939.

After Independence: Myanmar (then called Burma) proclaimed its independence on Jan. 4, 1948, and proudly hoisted this flag the same day.

From the opaque way it was chosen to the muddled messages it sends, Myanmar’s national flag is an unwelcome reminder of the former junta’s decades of misrule

included. Moreover, red, which means valor and decisiveness, should also be portrayed.”

According to the report, the committee responsible for the redesign studied the flags of 194 nations, as well as Myanmar flags from the Bagan, Inwa, Konbaung and pre-independence periods.

What it does not note is that the new flag is very similar to one that was used between 1943 and 1945, when Myanmar was under Japanese occupation. The main difference is

Myanmar’s

symbol of ethnic Burman domination.

Interestingly, it has retained its favor among dissidents, most notably the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) and the All Burma Students’ Democratic Front, both of which feature the “fighting peacock” design prominently on their flags.

that it replaces the emblem of the royal peacock (a symbol of the Konbaung dynasty, which ended when the British seized control of the country) with a white star. The reasons for this throwback to an era that few would regard as a high point in Myanmar history are not well understood, but the decision to leave out the peacock is less of a mystery.

Although the peacock was long associated with Myanmar’s former monarchy, during the era of British rule it also became a symbol of resistance—something that the country’s military rulers were never very keen on. So even though the former junta was happy to adopt the trappings of royalty in some cases (the name of the capital, Naypyitaw, for instance, means “abode of kings”), it steered clear of the peacock when picking a new flag. Actually, however, the peacock was officially disowned by the state much earlier. In 1947, the year before Myanmar regained its independence, a 10-member committee formed by the National Assembly decided to drop the peacock once and for all because of its association with autocratic rule, and because it could be construed as a

It is also worth noting that the stripe colors of the current flag are the same as those used in the flag of the Dobama Asiayone (We Burmans Association), founded in 1930 by patriotic youths opposed to British rule. The records say that the association hoisted a flag with yellow, green and red stripes and a peacock in the middle when it held its first conference in March 1935. The yellow stripe was said to represent the development of religion and education, while the green stood for prosperity and the red symbolized the bravery of the Myanmar people.

So, even as the designers of the current flag were careful to avoid one symbol associated with resistance, they appeared to hearken back to another one with their choice of colors.

Even more bizarrely, the new design could even be seen as a rare case of flag plagiarism. Some observers have noted that the flag that now flies over Myanmar’s government buildings is identical to that of the National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma (NCGUB), the now disbanded government-in-exile formed after the former junta refused to recognize the results of the NLD’s landslide election victory in 1990. The NCGUB adopted its flag in 1992, and in a press release issued shortly before the 2008 referendum, its then foreign minister, U Bo Hla Tint, accused the regime of blatantly stealing its flag.

Whether this is actually what happened or not, many now feel that Myanmar deserves a better flag— one that represents the democratic aspirations of its people, rather than the whims of the former ruling generals.

As one freelance tour guide put it on the occasion of the flag’s third anniversary, “It looks like a traffic light. I would say that for 99 percent of Myanmar people, there is no love for this flag.”

Today: Myanmar adopted a new state flag on Oct. 21, 2010, in accordance with the State Constitution approved by a national referendum held in May 2008.

Military Era: The armed forces first seized power in March 1962. This flag, introduced when a one-party socialist regime was created in 1974, was not replaced until 2010.

Today: Myanmar adopted a new state flag on Oct. 21, 2010, in accordance with the State Constitution approved by a national referendum held in May 2008.

Military Era: The armed forces first seized power in March 1962. This flag, introduced when a one-party socialist regime was created in 1974, was not replaced until 2010.

By LAWI WENG, SAW YAN NAING and SANAY LIN / BAGO REGION

By LAWI WENG, SAW YAN NAING and SANAY LIN / BAGO REGION

Above: U Myint Wai, a concerned local citizen, stands over the skull of an elephant killed in a Bago forest earlier this year.

Left: U Myint Wai’s son holds more of the animal’s bones, scattered in a stream deep in the forest. An arrest was made in early November in connection with the illegal killing.

Above: U Myint Wai, a concerned local citizen, stands over the skull of an elephant killed in a Bago forest earlier this year.

Left: U Myint Wai’s son holds more of the animal’s bones, scattered in a stream deep in the forest. An arrest was made in early November in connection with the illegal killing.

From Mile 58 on the newly built Yangon-Naypyitaw highway, U Myint Wai walks about four miles (6 km) into jungle in the Bago Yoma mountain range.

He is returning to a site where he recently discovered the skeletons of several dead elephants, and he talks along the way about the hunters who killed them, hoping to trade their skins or valuable tusks.

“More than 20 wild elephants were killed by hunters [this year], going by what I’ve seen myself and what I’ve heard from villagers and workers,” he says.

“These hunters have been slaughtering wild elephants since 2010. I estimate that several dozen elephants have been killed so far.”

U Myint Wai, a local resident of Bago Region, north of Yangon, points to a homemade map of the mountain range, identifying 11 sites where dead carcasses have been found recently. Some sites are deep in the jungle, he says, adding that

he walked for several days to get to them.

One of the closest sites lies two hours from the highway, over a rough walking path and across small muddy streams filled with leeches.

U Myint Wai shows the skeleton of one animal lying in a stream, hidden under bamboo brush. The elephant was killed around April of this year, he says. Some of its rib bones are still scattered about in the water.

Gesturing towards the skull, also lying in the stream, he says the elephant was probably aged around fifty or sixty. The skull is pierced with two bullet holes.

In late October, the Myanmar Army and Bago Region police launched an operation in Baw Ni, a village in Daik-U Township near where the killing occurred, to investigate the slaughter and go after the poachers.

Police later arrested a suspect named U Kar Zin in Thaton Township, Mon State. The man, who is

Above: Demand for ivory is driving the deadly trade in elephant tusks.

Right: U Myint Wai examines the bones of the elephant killed around April in Bago Region.

Below left: A bullet hole is seen in the elephant’s skull.

Below right: A monk stands by a footprint of a wild elephant in Kyarchaung, a village in Taikkyi Township, Yangon Region. Elephant-human conflict is becoming more common as the animals lose natural forest habitats and try to find food near villages.

from the same township, is married to a woman from Baw Ni. Two local villagers were being brought in as witnesses in the case, according to Daik-U Police Sergeant Tin Oo.

On Jan. 29 of this year, some 30 miles (48 km) away, another poacher was arrested after an operation by police, forest officials and local village administrators in Kyauktaga Township, following the discovery of a dead elephant in a nearby forest. The elephant’s body and two tusks were confiscated.

Hunting wild elephants may be against the law, but that is not stopping poachers, who are just the first link in an international trade whose end point is mainly China. Besides the precious tusks, the skin can also fetch high prices in illegal markets.

To counter this growing threat to Myanmar’s elephant population, the Forestry Department has established a new elephant sanctuary in the Bago Yoma mountain range. However, according to Antony J.

Lynam, the Asian regional advisor to the New York-based Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), there are more elephants outside the new North Zarmari elephant sanctuary than inside, due to disturbances from logging as well as poaching by organized gangs.

“A lot of resources will need to be put in to protect the sanctuary if the elephants are to return to the forest,” said Mr. Lynam.

He said that as well as poaching elephants in Myanmar for their ivory and skin, there is also a thriving trade in live elephants, especially calves, into Thailand for tourism.

“Any country that has elephants has a risk of poaching as there is a high level of demand for ivory in China and high demand for live elephants in Thailand. Myanmar, being a neighbor to these two countries, is at high risk that wild elephants will be poached for one reason or the other.

“Added to this, with the forests

being reduced in size and fragmented, elephants are finding themselves living closer to people who farm and encroach on forests, and this leads to conflicts, with elephants getting killed,” said Mr. Lynam.

Under these conditions, poachers appear to be growing ever more brazen in their pursuit of their quarry. In one recent incident, a group of hunters continued shooting even as they chased three elephants right into Baw Ni late at night.

“This illegal trade has been going on for a long time. Nobody seems interested or aware, but it’s getting worse every year,” says U Myint Wai, adding that he raised the issue with U Nyan Win, the secretary of the opposition National League for Democracy, when they met recently.

“I can’t sit and let this happen any longer. I feel bad for these animals. So I decided to raise this issue by reporting this case to the local police. I also asked an MP to raise the issue in Parliament.”

He says his journeys into the jungle are risky. “I have no gun, but they [the hunters] do. I was even threatened by some local people who were involved. They said they knew who was talking to the media about the elephant slaughters.”

Local people say there are different groups of elephant hunters who use a waterway at the Baw Ni dam to carry the skins by boats after killing the animals.

Ironically, elephants are not safe even on land that has been seized by the government for national parks, according to Saw Htoo Thar Poe of the WCS. The Yangon-Naypyitaw highway, for example, passes right through a national park in the Bago Yoma, where other parcels of supposedly protected land have also been sold to logging and rubber companies.

According to U Kyaw Myint of the Alaungdaw Kathapa National Park in Sagaing Region, Myanmar’s largest national park, the Bago Yoma has the highest number of reported cases of elephant poaching, because it is the area with the largest population of wild elephants in the country.

“Most poachers use homemade guns and poison arrows” to kill their

prey, he explained, adding that the government suspects that organized gangs are also involved in the illegal trade in elephant parts.

“Besides poachers, some elephants are also killed by landmines,” he added.

Although there is no official figure for the number of wild elephants in Myanmar, they are known to populate several parts of the country, including the Bago Yoma and Rakhine Yoma mountain ranges, Tanintharyi and Ayeyarwady regions, and Kayin and Kachin states.

Elephant poaching is a problem almost everywhere that wild elephants are found in Myanmar. In

January of this year, for instance, residents and lawmakers from Ngaputaw Township in Ayeyarwady Region reported that five elephants had been killed in the area within a period of seven months.

Each death represents a major loss to local wild elephant populations. Locals living in the Bago Yoma say that even here, the number has dwindled to just over 150. And the pressure on existing herds is growing all the time.

“In the past, there was jungle all around the Bago Yoma. Now much of it has been cut down,” says U Han Zaw Win, an environmentalist based in the area. “It’s hard for the

Above: A villager in Hmawbi, north of Yangon, climbs down from a makeshift watchtower used to look out for wild elephants.

Left: Mahouts ride an elephant in Hmawbi Township past a sign that says to be aware of the danger of elephants.

elephants to survive.”

Globally, the picture is just as dire. According to WCS, more than 17,000 elephants, or 8 percent of the world population, were killed in 2011 alone.

“Every animal killed is a percentage of the population lost,” said WCS’s Mr. Lynam.

• In 1994, Myanmar enacted laws against poaching and trading in wildlife, with penalties of up to seven years in jail and/or fines of up to 70,000 kyat.

• In 1997, Myanmar signed the Convention on the International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES).

• In 2010, Myanmar chaired the 5th annual meeting of the Asean Wildlife Enforcement Network (Asean-WEN). This is the world’s largest wildlife law enforcement network and involves police, customs and environmental agencies from all 10 countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

• In 2011 Myanmar created a national inter-agency Wildlife Law Enforcement Task Force.

• However, enforcement in Myanmar is still weak. Numerous reports indicate there is a significant, barely checked trade in elephants, Asiatic bears, sun bears, tigers, leopards, snow leopards, cloud leopards, turtles, tortoises, and pangolins.

• Arrests of poachers in Myanmar appear to be on the rise, though nowhere near enough to make a serious dent in the trade.

• Although the sale of ivory is illegal, it is available to buy in retail outlets in Yangon, including at Bogyoke Market, as well as in Mandalay, Tachilek, Myawaddy and other centers.

• As Myanmar begins its term as the chair of Asean for the coming year, conservationists are calling on the government to show leadership in regional efforts to tackle the enormous illegal regional trade in wildlife.

On the challenges ahead: “So building the network is challenge number one. Getting the distribution to reach everyone is challenge number two. And then, of course, bringing the prices to such a level that they can actually afford it. Because you can be fooled by walking around the streets of Yangon— the affordability level in this country outside the cities is totally different.”

On knock-on effects:

“This is about creating a business where it’s not like we are going to do everything. Our philosophy is that what we are good at is to do the big heavy lifting. All the others will start to create businesses around us. Mom-and-Pop stores can suddenly sell SIM cards.”

On corruption:

“When it comes to corruption our philosophy is very simple, and as we’re operating in many markets in the world, this is a challenge that we are faced with in all our markets. We have zero tolerance for corruption and we just have to work on that basis.”

Myanmar’s drought of SIM cards is nearly over. The tiny plastic chips have in recent years been limited in supply. Distribution has been only through lotteries, driving a lucrative black market where they are peddled for hundreds of dollars each.

Sometime in the middle of the 2014 rainy season, however, the country’s major cities, at least, can expect a flood of affordable SIM cards.

Making mobile services available across the country is a big task, but there has been no shortage of international firms keen to get involved in setting up decent telecommunications, a vital prerequisite to Myanmar’s development in other sectors.

“This is the biggest telecoms opportunity in the world today,” Ross Cormack, CEO of Ooredoo Myanmar, told The Irrawaddy in November. The Qatari firm, alongside Norway’s Telenor, was selected in

market.

technology to this beautiful country to allow Myanmar to leapfrog back into its position as the jewel of Asia,” said Mr. Cormack.

There were many big firms among the losers in the tender, but the government is reportedly planning to issue more licenses before long.

Additionally, runners up Orange of France, along with SingTel of Singapore and Britain’s Vodafone, are in talks with Myanmar Post and Telecommunications (MPT) about helping the existing provider to compete with the newcomers, according to a recent report in the Financial Times. Officials have said there are plans to fully separate the state-owned MPT, and Yatanarpon Teleport, from the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology.

The Telecoms Law now in force will govern the sector, but the all-important regulations—the detailed rules of the game—are yet to be finalized. A public consultation launched in early November by the government seeks feedback on a draft set of regulations, which it says are in line with international best practice.

The regulations up for discussion include detailed guidelines about the mobile spectrum, how fair competition will be enforced, and how companies will be licensed. “The overarching principles of the Licensing Rules are to establish a multi-service licensing framework that provides transparency to all licensees and end users, promotes market entry, and creates a level playing field in the telecommunications sector,” the consultation document states.

On dealing with the Myanmar government:

“I would like to pay tribute to the government of the Union of Myanmar because everything they said they were going to do, they’ve done. And they’ve done it according to the timeline that they said they were going to do it. So it’s really fascinating. This is an example to every country in the world.”

On Corporate Social Responsibility:

July from dozens of firms that entered a competitive tender to be the first two private mobile phone operators licensed in Myanmar.

With the Myanmar Telecommunications Law enacted on Oct. 8, and licenses expected to be finalized before the end of 2013, both companies have promised to begin selling unlimited numbers of SIM cards, complete with 3G technology, for 1,500 kyat, or about US $1.50, in the middle of next year.

“We’re bringing the latest

John Lichtefeld, a foreign legal consultant with Singapore-based law firm Kelvin Chia’s Yangon office, said while the law makes mention of competition, most of the detail of how a fair market will be enforced is in the regulations.

“While it’s great that the language [on competition] is in the law, we’re going to have to wait to see how the rules and regulations expand on these prohibitions against anti-competitive practices, and how those prohibitions will be enforced,” he said.

And that competition may be fierce in coming years.

“We’re on record as saying that we will spend $60 million in the first 10 years on CSR. But actually CSR takes many forms and it’s not just the money, it’s the support that we can give to people in the community that makes the difference.”

On new competitors:

“Honestly, we don’t mind competition. It’s what gets us out of bed in the morning. But being serious, we read the same as you do [about new market entrants]. We don’t know how the process is working. MPT, by the way, are already the operator who understands the country, they are a strong competitor in their own right.”

A man talks on his mobile phone in Yangon.“This is seen as a big opportunity by global telcos to do business in a virtually untapped market,” said Vivek Roy, a research analyst at Londonbased Informa Telecoms & Media, who described the market as “pristine”—at the end of 2012 only about 6 percent of the population had a mobile phone.

Although the first two licenses are already awarded, he said, big companies were showing keen interest in Myanmar’s telecoms market. He cited moves this year by Internet service provider Hutchison Global Communications Limited of Hong Kong, Japanese tech firms NTT Communications, NEC and Sumitomo and Malaysia’s U Mobile to enter

different parts of the nascent telecoms sector.

“Still, we expect that generating revenues is going to be tough for license winners, Ooredoo and Telenor, since Myanmar has a sorry state of existing telecom infrastructure, including grid electricity coverage, poor road connectivity, low GDP per capita and high handset costs,” said Mr. Roy.

The telecom sector’s current state is an acute reminder, especially to potential foreign investors, of just how far behind Myanmar has fallen after years of military misrule. Hence, Telenor and Ooredoo are primarily charged with expanding access to telecoms rapidly.

In the meantime, to avoid the embarrassment of poor connectivity at December’s SEA Games, a Japanesefunded quick fix has seen temporary 4G infrastructure installed at venues.

The head start from being the first licensees is offset by the obligations to build a modern mobile network almost from scratch, said Mr. Roy. Ooredoo, hailing from the natural gasrich emirate of Qatar, has said it will invest $15 billion in Myanmar over the 15 years of its license. Telenor declined to provide a figure for its investment, but Mr. Roy said it was likely to be considerably lower than Ooredoo’s.

Hundreds of transmission towers

will be required to provide coverage, especially in rural areas, where about 70 percent of the population resides and power is scarce.

“Although diesel-powered base stations would be the short-term solution, they would drive up opex [operating expenditure], so over the longer term, operators would need to look at more green, cost effective options,” Mr. Roy said.

Petter Furberg, CEO of Telenor Myanmar, said the government was keen to get the companies to enter into agreements to share towers, reducing the investment required from each to build the infrastructure.

“One tower costs [an estimated] $100,000,” he said. “Particularly here in Myanmar you have to import all the steel and a lot of concrete, which means a total waste of money at a time when the country needs to spend all its investments on building infrastructure as efficiently as possible.”

Ooredoo is also open to sharing towers, which could also include the existing government-linked mobile companies.

Adding further complexity, every tower built across the country will involve acquiring land and gaining planning permission—which will likely cause problems in Myanmar, where land ownership is controversial after years of seizures, ill-conceived concessions to cronies and often-forced migration.

“Planning law is complicated and even the government is not exactly certain how we can get all the approvals. But we do have the commitment of the government to ensure that they do happen,” said Ooredoo’s Mr. Cormack, whose company has set itself the ambitious goal of reaching 97 percent of Myanmar’s estimated 60 million population in five years. “It is a challenge.”

Mr. Furberg said at least 80 percent of the country will be able to get Telenor services in five years.

“It’s a challenge,” the Telenor Myanmar CEO said, echoing his competitor. “It’s not an easy country to operate in. It’s not an easy country to build infrastructure in, so we’re very humbled by the task.”

“This is seen as a big opportunity by global telcos to do business in a virtually untapped market.”

—research analyst Vivek Roy

From the finest raw materials to innovative recipes, we transform local food into international cuisine.

Like most residents of Myanmar’s largest city, U Myint Maung never imagined that he would one day be able to buy a car of his own. Now, however, the 63-year-old retired government official is the proud owner of a used Toyota Belta—a vehicle that

not so long ago would have been far beyond his means.

Until very recently, Myanmar was probably one of the most expensive countries in the world to purchase a car. Under the former military regime, import restrictions sent prices sky high, making it impossible for all but

the well-connected to buy high-end vehicles or even relatively new used models.

That all changed in 2011, when the current quasi-civilian government took power and started steadily opening up the country’s economy. Since then, the Ministry of Transport has changed the rules for importing cars eight times, starting with a scheme that allowed owners of decades-old clunkers to replace them with newer models.

That first step toward liberalizing the domestic automobile market saw the import of more than 100,000 cars, mostly from Japan and South Korea. Then, in 2012, the government announced that anyone with a foreign savings account could import cars. Soon car showrooms were placing more orders for vehicles from Japan.

According to Daw Mar Lar, the director of the Best Auto car showroom in Yangon, small used cars with 1.3-liter engines from Japan are especially popular because they’re reasonably priced and generally in good condition. Another plus, she said, is that it’s easy to find spare parts.

Dealers say that over the past two years, used cars from Japan—which can be shipped to Yangon from any major port in Japan within about three weeks of receiving payment— have made up about 95 percent of sales in a rapidly expanding market.

“Nissan vans, Suzukis, the Toyota Probox, the Honda Fit, the Honda Vitz and the Nissan March are now in strong demand in my showroom,” said Daw Mar Lar. “Most of these models sell for around 10 million kyat (US $10,340).”

“Demand has increased a lot, because in the past, such imported cars would have cost several times as much as they do now,” she added.

Import licenses can be issued by several different ministries, including the ministries of transport, commerce and customs, and must specify the age and make of the vehicle to be imported.

Several Toyota models, including the Harrier, Mark II, Mark X, Hilux Surf, Probox, Belta and Landcruiser, are among the most popular.

Growing demand for cars has also brought increasing competition among car dealers. In Yangon, more than 200 showrooms have opened since 2011. Each one is required to deposit $100,000 with the government and provide a surety of 300 million kyat ($310,000), plus pay an annual fee of $900 to the government, said the owner of one showroom.

These expenses mean that many dealers still prefer to operate out of one of three major trading centers that dominated Yangon’s car market until 2011. According to Ko Tun Myat, a broker at the St. John’s trading center in Lanmadaw Township, cars sold here typically cost about 500,000 kyat ($517) less than the same models on sale in showrooms. On the other hand, he said, his customers must get a license plate within 20 days of making a purchase, whereas those who buy from showrooms have up to a year before they have to replace their dealer plates.

“But in the end, it all depends on what the customer wants,” he said. “If someone likes a car they see here, they’ll buy it. But if they can get what they’re looking for at a reasonable price

from a showroom, they’ll buy it there.”

A bigger worry, he said, is that prices overall are falling—something that he hopes will change next year, when the government is expected to allow the import of 2009 models.

Although Japanese cars have a clear lead in the race to capitalize on Myanmar’s car craze, other country’s carmakers are also hoping to position themselves for future growth in one of the world’s last large frontier markets. US automaker Ford and Mercedes Benz from Germany already have a presence here, and are soon to be joined by Jaguar Land Rover, a British brand now owned by India’s Tata Motors.

But it could be Japan’s nearest neighbor, South Korea, that offers the stiffest challenge to Japanese preeminence.

Hyundai Motors, which opened its first showroom in August and has plans to open 14 dealerships across

the country by 2018, said it hopes to capitalize on the popularity of South Korean pop culture in Myanmar to expand its market share in the country.

“Young people in Myanmar who watch Korean dramas visit our showroom and look for cars that were shown in the dramas,” said Oh Seiyoung, the chief executive of Kolao Holdings, the sole dealer for Hyundai in Myanmar, according to a report by Reuters. “Hyundai is really keen on the Myanmar market.”