EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Aung Zaw

MANAGER: Win Thu

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Aung Zaw

MANAGER: Win Thu

The Irrawaddy magazine covers Myanmar, its neighbors and Southeast Asia. The magazine is published by Irrawaddy Publishing Group (IPG) which was established by Myanmar journalists living in exile in 1993.

EDITOR (English Edition): Kyaw Zwa Moe

COPY DESK: Neil Lawrence; Paul Vrieze; Samantha Michaels

CONTRIBUTORS to this issue: Aung Zaw; Kyaw Zwa Moe; Subir Bhaumik; Vincenzo Floramo; Kyaw Phyo Tha; Paul Vrieze; Samantha Michaels; Sean Havey; Andrew Kaspar; Seamus Martov; Yan Pai; Simon Roughneen; William Boot

PHOTOGRAPHERS: JPaing; Steve Tickner

LAYOUT DESIGNER: Banjong Banriankit

REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS MAILING ADDRESS: The Irrawaddy, P.O. Box 242, CMU Post Offi ce, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

YANGON BUREAU : No. 197, 2nd Floor, 32nd Street (Upper Block), Pabedan Township, Yangon, Myanmar. TEL: 01 388521, 01 389762

EMAIL: editors@irrawaddy.org

SALES&ADVERTISING: advertising@irrawaddy.org

PRINTER: Chotana Printing (Chiang Mai, Thailand)

PUBLISHER: Thaung Win (Temp-1728)

14 | analysis: Putting a New Face on Myanmar’s Military?

After decades of being a byword for brutality, Myanmar’s Tatmadaw is trying to redefine its role under the leadership of a new commander-in-chief

18 |

life: General Turned Restaurateur No Longer Has Time for Golf

A former general who heeded the call to clean up Myanmar’s government falls from grace—but lands on his feet

20 |

border: All Quiet on the Wa Front?

Relations between Myanmar’s largest ethnic armed group and Naypyitaw could be in for a rough ride

22 |

border: One Year On, Tensions in Rakhine Remain High

A year after the outbreak of sectarian violence in Rakhine State, government policies seem to be strengthening divisions

|

The skyline of Myanmar’s largest city undergoes its most rapid changes in decades, as developers scramble to cash in on a dramatic rise in demand for prime property

34 | business: Trade with Myanmar Key Part of US Pivot to Asia

By expanding its role in the Myanmar economy, the United States hopes to slow China’s growing sway over Southeast Asia

38 | business: World Economic Forum: What They Said

There was no shortage of discussion, debate and opinion at the unprecedented gathering of industry and political leaders in Naypyitaw in June. A range of participants shared their thoughts with Simon Roughneen.

42 | Culture: A Bit of Thai History, on the Outskirts of Mandalay

More than two centuries after his death, Thailand rediscovers a long-forgotten king and wins a reprieve for his final resting place

The Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s armed forces, has long been accused of committing numerous human rights abuses, including atrocities against civilians in conflict zones and recruiting child soldiers. Under the current quasi-civilian government, however, it has tried to improve its image, acquired over its nearly 50-year rule over Myanmar.

Recently, Lt-Gen Myint Soe, the Tatmadaw commander who oversees military operations in Kachin State, became the first senior military leader in decades to speak to the media about some of these issues. In an interview with The Irrawaddy’s Nyein Nyein and May Kha, he also answered questions about the military’s role in talks aimed at ending the conflict in Kachin State.

Speaking soon after the Tatmadaw and the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) reached a tentative peace pact in late May, Lt-Gen Myint Soe warned against believing all the reports of crimes allegedly committed by the Tatmadaw. He also explained why, despite ceasefire agreements reached in other parts of the country, clashes continue.

On another issue—the Tatmadaw’s major commercial enterprises—he was more reticent. While declining to discuss the military’s still-dominant role in the domestic economy, he attempted to justify it by saying the military needed to be “independent” of the government.

What is the Tatmadaw’s role in the peace process?

The peace process is done. What we need to do now is protect our country. We have a plan to give back farmland, with our soldiers assisting in the cultivation of crops if necessary. After the ceasefi re agreement, we’re focusing on pragmatic plans to serve the people.

When will the Tatmadaw return the land it confiscated?

I’m just responsible for military campaigns. This issue should be handled by the military’s division of transportation. I don’t know the details.

Myanmar’s military has long inspired fear in the people. How will the Tatmadaw show that it

is changing, and that it will serve the people?

Just look at the Meikhtila crisis, when the military restored peace and order [following anti-Muslim riots]. In the Kachin peace process, we’ve held discussions with the KIO [Kachin Independence Organization], and they believe what we’re doing. The KIO has accepted that the [government] army has changed its stance. In this way, I hope the public believes us.

What do you think of the Tatmadaw’s reputation?

The Tatmadaw has been changing from era to era. Under the current Constitution, the role of the armed forces is to serve the state, which the public now has the right to elect. In the past, people may have felt that we soldiers were good for nothing, which may have been true before, but not anymore.

Bluntly speaking, I was also one of those who hated the army, especially during the U Thant crisis [in December 1974, when students and the socialist regime of former dictator Gen Ne Win clashed over the burial of the late UN Secretary-General U Thant]. I hated the soldiers a lot then. But later I joined the army, and I had to obey orders. Now the Tatmadaw has changed. Even Daw Dwe Bu, one of the Kachin representatives, said that she was afraid of the [Myanmar] soldiers before, but after meeting them, now she feels they are friendly.

Some soldiers may be proud, but we are not all the same. Some may have been selfish or egoistic, and some may think all are like that, but it’s not really true.

Although President U Thein Sein called for a unilateral ceasefire [in Kachin State] late last year, the military continued fighting. Does this mean that the Tatmadaw is above the president?

The president issued an order on Dec. 10, 2012, calling for an end to military offensives, although we could still defend ourselves. But here, opinions differ. For example, if Maj-

Gen Gun Maw [one of the KIO’s chief negotiators in the talks] is traveling back [to his base from governmentcontrolled areas], I have to arrange for his security, so I will order my soldiers to shoot any suspect who threatens him. If they shoot, can you say a clash has erupted? Yes. But the soldier was shooting due to the situation. Many say the military is above the president because they don’t fully understand the nature of the military.

We have been working on the issue with Unicef. We don’t have child soldiers. But some soldiers told us they were 18, when in fact they were younger. If we find a soldier is younger than 18 we let them go.

Is there any plan to hold elections for military representatives to Parliament in the future?

No. Military representatives will only be chosen by the chief of staff. There is no voting in the military.

There were reports of crimes committed by the military in Kachin State last year, yet no one has been punished. How does the military deal with criminals in its ranks?

In the military, every soldier has to obey two types of law: military law and civil law. As the military laws are stricter, there is a court of inquiry and, if found guilty, a soldier will be arrested and punished accordingly.

There have been frequent reports of abuses by soldiers. Is it a systemic problem, or are there just a few bad apples?

How many cases have you heard? Don’t believe everything you hear. There are many rumors, endless rumors. You

should ask the military’s information department [for the facts].

How are the military’s funds looking?

We don’t have any problems.

Does the military have any enterprises it’s making mo ney from?

I can’t answer that. But I can say the military will never burden the government. We can stand on our own, but we need a budget to grow.

Are there any plans in the works to expand Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Ltd, which has served as the economic backbone of the armed forces?

I can’t say, as I’m not the CEO. We are trying to be independent, that’s all I can say.

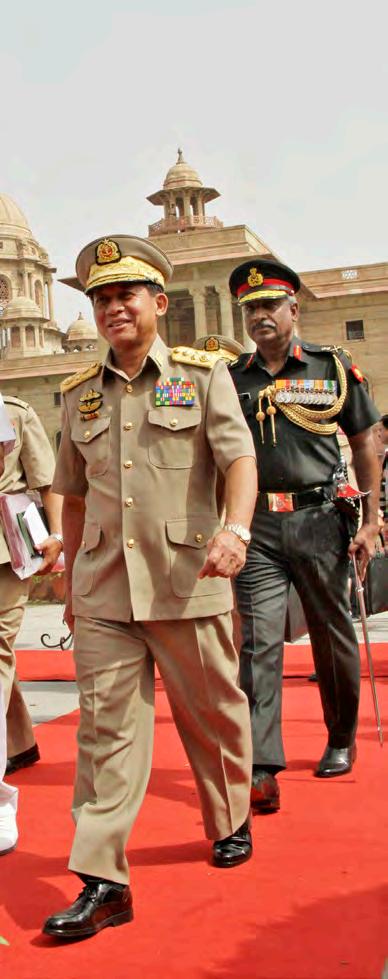

Lt-Gen Myint Soe arrives for peace talks with the Kachin Independence Organization in Myitkyina in late May.

Lt-Gen Myint Soe arrives for peace talks with the Kachin Independence Organization in Myitkyina in late May.

—U Shwe Mann, the speaker of the Lower House of Parliament and leader of the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party, on the possibility of a coalition with the opposition National League for Democracy after elections in 2015

—Buddhist monk U Dhammapiya on media coverage of recent waves of religious violence in Myanmar

“In Myanmar, the Muslims are the victims; over here the Buddhists are the victims.”

—Amar Sing Ishar Singh, the deputy police chief of Kuala Lumpur, on a string of attacks targeting Buddhist Myanmars in early June

“We all need to know it, so we plan to teach children from primary school onwards.”

—U Win Mra, the chairman of Myanmar’s National Human Rights Commission, on plans to introduce the subject of human rights into school syllabuses

“I believe time will decide on this matter. But the important thing here is to have confidence between Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and us.”

“There are many media that report ethically. But there are some which get backing from some sort of organizations. We are just requesting you to write the news with the right information.”

It’s a bird, it’s a plane… No, it’s U Thein Sein

A series of deadly attacks apparently targeting Myanmar Buddhists in Malaysia claimed at least five lives in late May and

early June. The violence was widely believed to have been related to a wave of antiMuslim riots that has swept through Myanmar since the

from cardiovascular disease for the past 10 years.

beginning of the year, most recently hitting Lashio, Shan State, on May 28. Malaysian police rounded up hundreds of Myanmar nationals in connection with the attacks, which occurred between May 30 and June 7, and Myanmar government officials flew to Malaysia to discuss the problem with their Malaysian counterparts. Myanmar nationals wishing to leave the country were offered financial support and discounted airfares by some of Myanmar’s richest businessmen, but migrant rights groups said that bureaucratic delays at the Myanmar embassy was preventing many from returning.

Family, friends and fans paid tribute to songwriter Kyaw Kyaw Aung, better known as KAT, on June 3, 2013.

Kyaw Kyaw Aung, the popular songwriter better known to his fans as KAT, died on June 1 of heart failure, aged 48. Hundreds of family, friends and fans came to pay their respects in Yangon for the acclaimed writer of lyrics to some of Myanmar’s bestloved pop songs. Members of popular rock band Iron Cross and famous singers such as Lay Phyu and R Zarni were among the mourners. According to a close friend, Kyaw Kyaw Aung lost consciousness after choking on some betel nut, and died before reaching the nearest hospital. He had suffered

Britain’s top general was in Myanmar on June 3 to build ties with the country’s military, which until recently was ostracized in the West. General Sir David Richards became the first Western military chief to visit Myanmar since the country made the transition to quasi-civilian rule in 2011. In addition to meeting with Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing, the commander-in-chief of the Myanmar armed forces, Gen Richards met with President U Thein Sein and opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi during his twoday visit, state-run media reported. The move follows Australia’s decision earlier in the year to open military ties with Myanmar.

Former US Top Diplomat Praises Myanmar’s ‘Overdue’ Reforms

Madeleine Albright, the former US Secretary of State, congratulated Myanmar on the changes the country has introduced since 2011 during a speech delivered at Yangon University on June 4. Ms. Albright, who was visiting Myanmar for the first time since 1995, when she was still serving as the top US diplomat, called the reforms “long overdue,” but also urged further patience with the ongoing transition to democracy. As chairperson of the non-partisan National Democratic Institute, she also said that the institute wanted to help Myanmar “create a robust and durable democracy.”

Members of the 88 Generation Students group have called on the main backer of the controversial Myitsone hydroelectric dam in northern Myanmar’s Kachin State to completely shut down the suspended project. In a statement released on June 7, the group said that a delegation visiting China earlier that week made the request during a meeting with officials from the staterun China Power Investment Corporation (CPI), the primary investor in the US $3.6 billion hydropower project. The project was suspended in September 2011 because of concerns about its environmental, economic and cultural impact. In May, CPI expressed a desire to restart the project in a meeting with a National League for Democracy delegation that had traveled to China at the invitation of the ruling Communist Party.

The police have launched an investigation after suspected armed insurgents hijacked a bus traveling from southern Myanmar to Yangon, robbing passengers of more than 4 million kyat (US $4,210) and killing two people. The bus was hijacked by five armed passengers on June 8 while driving to Yangon from Mon State, local police said, adding that the attackers held the bus driver at gunpoint before forcing him off the road in Mon State’s Thaton Township and attacking him and his assistant. “The bullet shells we collected from the crime scene were from Brazil and were made for a 9 mm pistol,” the township police chief said. “Ordinary

people don’t have access to that kind of weapon.”

Leaders of the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS), the political arm of the Shan State Army-South, met with President U Thein Sein for the first time on June 10. The RCSS delegation, led by Lt-Gen Yawd Serk, traveled to Naypyitaw for the talks with the president, who was joined by the government’s chief peace negotiator U Aung Min and President’s Office Minister U Soe Thane. The two sides agreed to work together on the repositioning of troops, de-escalation of hostilities and the formation of a conflict-monitoring team, said U Hla Maung Shwe, a peace broker with the governmentaffiliated Myanmar Peace Center. They also discussed the establishment of an allinclusive political dialogue

and the issues of internally displaced persons and food security for the local population.

Lt-Gen Yawd Serk, center, dresses President U Thein Sein in traditional Shan attire during their meeting in Naypyitaw on June 10, 2013.

Myanma Airways Grounds

MA60s after Landing Mishaps

Myanmar’s state airline said it would stop flying its Chinese-made MA60 planes following its second accident with the turboprop model in less than a month. Myanma Airways administration manager Hla Htay Aung said the

airline will ground its three MA60s for the time being. One swerved off the runway on June 10 while landing in Kawthaung in southeastern Myanmar, causing no injuries but damaging both propellers. Another Myanma Airways MA60 shot past the end of the runway on May 16 at Monghsat in northern Shan State when its brakes reportedly failed. A wing and a wheel were damaged, and two passengers suffered broken arms.

Senior Buddhist monks held a two-day conference in Hmawbi, Yangon Region, on June 13-14 to call for measures to end recent tensions between Buddhists and Muslims in Myanmar. “We promote peaceful coexistence with all those who are living in the country,” the conference’s 227 participants said in a joint state-

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the leader of the National League for Democracy (NLD), met with the leaders of five ethnic parties on June 18 to discuss efforts to amend Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution and pave the way for the longer-term goal of creating a federal political system. Ethnic leaders who attended the 90-minute meeting said that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi agreed that the country should move toward federalism, but should do so gradually. Meanwhile, a week earlier, 15 ethnic groups agreed following a meeting in Taunggyi, Shan State, to join forces to form a political party ahead of general elections in 2015. The new party, to be called

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, second from left, walks up the steps to Myanmar’s Parliament with fellow National League for Democracy MPs on Jan. 16, 2013.

the Federated Union Party, hopes to “get on the same political level” as the ruling military-backed Union Solidarity and

Development Party and the NLD, said Oo Hla Saw, the general secretary of the Rakhine Nationalities Development Party.

ment. In response to claims that Buddhist monks had participated in anti-Muslim riots, it added: “We object to any actions, false accusations or statements against Buddhism which are detrimental to Buddhism and the dignity of Buddhist monks.” The monks also distanced themselves from a controversial proposal to restrict intermarriage between Buddhists and Muslims that was put forward by U Wirathu, a leader of the Buddhist nationalist 969 movement, on the first day of the conference.

The International Labor Organization (ILO) announced at its annual International Labor Conference in Geneva, Switzerland, that it would lift all remaining sanctions on Myanmar. The restrictions, imposed by the UN agency in 2000 in response to the former military junta’s use of forced labor, included a recommendation that the ILO’s 185 member states limit relations with Myanmar to avoid perpetuating the practice. ILO delegates temporarily suspended this restriction and lifted some others last year, but on June 18 voted to totally lift all punitive measures. Myanmar’s government welcomed the ILO’s move, saying it would help accelerate trade and investment. Critics said, however, that Myanmar’s military continues to used force labor in ethnic conflict zones.

Pagoda festivals have been a tradition in Mrauk U, the seat of a once-great Rakhine kingdom, for centuries. But this year’s festivities at the famous five-day Shitthaung Pagoda festival, held in late May, were interrupted by a curfew that has been in place since the outbreak of violence between Rakhine Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims one year ago. Some events, such as wrestling and long-boat racing, went ahead as usual, but others, including an allnight performance of traditional dance, had to be called off.

At this year’s World Economic Forum (WEF) on East Asia meeting, held in Naypyitaw in early June, opposition leader Daw Aung Suu Kyi reiterated her desire to become president of Myanmar. “I want to run for president and I’m quite frank about it,” she said at a debate held in the Myanmar capital.

There are certainly many who would like to see her realize her wish when the country next goes to the polls in 2015. My bet, however, is that it won’t come to pass, for the simple reason that there are too many people in positions of power who fear it.

For the men who once ruled Myanmar with an iron fist, the current political order is the best of all possible worlds, and one they will not relinquish willingly.

By KYAW ZWA MOEAfter decades of international criticism, Myanmar’s generals and ex-generals are now fêted around the world for introducing reforms. Far from facing justice for past crimes against the country’s citizens—including countless human rights violations and the theft of national assets—the leaders of the former military regime have either comfortably retired or assumed high positions in the current quasi-civilian government.

While the three areas of the state’s power—the government, the Parliament and the military—have competed among themselves for a greater share of power under the current system, they are not about to let their rivalry go too far, because they all know that they benefit from the status quo. Above all, they will not allow anyone to upset their efforts to reap the rewards of reform even as they maintain their overarching control.

This is why, I believe, the next president of Myanmar will be one of the leaders of the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), and not Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

As disappointing as this may be to her many supporters, however, all is not lost: There is still a very good chance that she could become vicepresident. The real question, then, is who will capture the top spot in 2015, and how that person will manage his

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi says she wants to be Myanmar’s president, but the powers that be aren’t likely to let that happen

relationship with the woman who would be president.

When U Thein Sein, Myanmar’s current president, was handpicked by former junta leader Snr-Gen Than Shwe to lead the quasi-civilian government that took over from the military in March 2011, he was widely expected to stay in office only for a single term. Now, however, that is not so certain, as he has expressed an interest in capitalizing on his success in winning international and domestic acceptance to seek another term in office. It seems, then, that he is now one of the main contenders for the presidency post-2015.

Unlike the last time, however, he will have a serious rival next time round: Lower House Speaker U Shwe Mann, another ex-general who previously occupied the third-highest position in the former military regime. In his current position, U Shwe Mann has won accolades for allowing Parliament to function as a forum for genuine debate, instead of merely acting as a rubber-stamping institution. At the WEF meeting in Naypyitaw, he told The Irrawaddy that he is also interested in becoming president.

Much has been made of the relationship between U Thein Sein and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi: It was their meeting several months after the present government was formed that set the stage for the dramatic changes that were to follow.

Far less has been said about how well U Shwe Mann gets on with Myanmar’s most famous political figure. Some analysts have suggested that the two see each other as rivals, but actually, the opposite seems to be true: It is now believed that they have become allies.

The key issue for Daw Aung San

Suu Kyi is whether she can win support for her efforts to change the 2008 Constitution, which bars her from becoming president on the grounds that she was married to a foreign national.

Shortly after she expressed her desire to become president, U Thein Sein said in a television interview that it was up to Parliament to amend the Constitution—signaling that he was not the one who would come to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s aid.

It is to U Shwe Mann, then, that she must turn if she wants to become president—or the next best thing, vice president.

generally regards U Shwe Mann as less reputable than President U Thein Sein. But the opposition leader has evidently decided that the risk she is taking is worth the potential reward.

So how does this fit with the problem of resistance to any change at all from Myanmar’s powerful vested interests?

No one in the government, the Parliament or the military wants to give Daw Aung San Suu Kyi the power that she seeks. However, with a “guardian” like U Shwe Mann, who still has considerable influence over the military, the one-time “enemy” of the former regime will be seen as less of a threat to their interests.

This will, in fact, be welcomed by those who fear another confrontation with The Lady, whose domestic and international support remains strong. By making this concession, they may hope to diminish the risk that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi—who will be 70 in 2015—will eventually achieve her long-term goal of becoming president.

For her part, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi may also be prepared to accept something less than the presidency in the interests of achieving national reconciliation.

And so it comes as no surprise that Myanmar’s most prominent parliamentarian and the Lower House speaker have, according to sources close to both figures, been informally discussing ways to amend the Constitution so that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi can become vice-president, in exchange for her backing of U Shwe Mann’s bid to become president.

This arrangement comes with possible risks to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s reputation, since the public

As vice-president, she can continue to work hard to heal the wounds of nearly 50 years of military rule, during which a tremendous division has grown between Myanmar’s supposed defenders and its people.

This will also reassure the international community, which is watching developments in Myanmar closely, that reforms are not losing momentum. For whether Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is president or vicepresident after 2015, the country will clearly be a very different place from what it was before.

Photo: r euter SAfter decades of being a byword for brutality, Myanmar’s Tatmadaw is trying to redefine its role under the leadership of a new commander-in-chief

By AUNG ZAWThis year’s Armed Forces Day was, by all accounts, spectacular. For the first time ever, Myanmar’s Tatmadaw, or armed forces, showed off its heavy weaponry and jet fighters as the commander-in-chief, Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing, received salutes from marching troops.

The speech that followed was far less remarkable, but if one listened closely, there was more to it than just the standard reiteration of the Myanmar military’s leading role in national affairs.

Although the military would, of course, continue to play a “leading political role” in accordance with Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution, which reserves a quarter of parliamentary seats for military officers, it would also “keep on marching to strengthen the democratic administrative path wished by the entire people,” said the Tatmadaw’s supreme commander.

Giving some weight to his professed commitment to staying on the democratic path was the presence of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who was attending the Armed Forces Day ceremony for the first time since emerging as Myanmar’s pro-democracy icon during the nationwide uprising against military rule in 1988.

The reason for The Lady’s surprise appearance at the event was probably related to the release of a report on the controversial Letpadaung copper mine in early March, according to political observers and members of her National League for Democracy (NLD). The report, drafted by a committee headed by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, recommended continuing with the Chinese-backed project, despite strong public opposition.

Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing inspects the troops during a parade to mark the 67th anniversary of Armed Forces Day in Naypyitaw on March 27, 2012.

Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing inspects the troops during a parade to mark the 67th anniversary of Armed Forces Day in Naypyitaw on March 27, 2012.

At any rate, her presence at the March 27 ceremony was less surprising than it might have been just a year or two ago. Since last year, she has repeatedly expressed her “affection” for the Tatmadaw, which was founded by her father, Gen Aung San, during Myanmar’s struggle against British colonial rule.

Last year, for instance, she told CNN’s Christiane Amanpour that she had no hard feelings toward the generals who kept her in detention for most of the past two decades. “I’ve always got on with people in the army,” she said. “This is why I have a soft spot for them even though I don’t like what they do—that’s different from not liking them.”

For his part, Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing also seems to have buried the hatchet with the woman long seen as the nemesis of Myanmar’s former military leaders. According to an NLD member who attended the ceremony

armed forces.

Very little is known about Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing, apart from the fact that he leapfrogged several four-star generals to get to his present position, including U Shwe Mann, the speaker of the Lower House of Parliament. This came as a surprise to many, given the fact that he had not spent much time in the War Office before becoming commander-in-chief. Clearly, however, it served an important purpose: to shield the former head of the junta and his family from the danger of a more powerful military leader turning against him.

Perhaps even more significantly, putting a relatively junior general in the top military post also helps to minimize the risk of the new commander-in-chief using his considerable constitutional powers against the president or Parliament. It also makes it easier to maintain harmony within the

with her, the commander-in-chief waved to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi as he departed from the ceremony in his car. She returned his wave, and also spoke with several young cadet army officers and generals who came to meet her after the ceremony.

Things have indeed changed since the days of the former junta, led by retired Snr-Gen Than Shwe. This is all the more striking considering the widely held view that the former strongman continues to wield considerable influence over military matters. It is believed that he not only handpicked Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing, but also his successor: According to well-informed sources, Lt-Gen Myat Htun Oo, another staunch Than Shwe loyalist, is next in line to lead the Tatmadaw once SnrGen Min Aung Hlaing’s term expires.

The question on many minds, however, is whether the current military leadership is ready to make a real break with the past. And perhaps the best way of assessing this is by looking closely at the man who, at least ostensibly, holds the reins of Myanmar’s still-powerful

powerful National Defense Security Council (NDSC), which brings together the commander-in-chief and senior members of the government, including the president. (There are rumors, however, that the NDSC’s regular meetings have been strained by tensions between President U Thein Sein and U Shwe Mann.)

Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing first came to the attention of observers in August 2009, when the then major general oversaw the military offensive against the Kokang ceasefire group known as the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, which had refused to become part of the Border Guard Force (BGF), formed in 2009 to bring ethnic ceasefire groups under Tatmadaw command.

A graduate of the 19th intake of the elite Defense Services Academy, SnrGen Min Aung Hlaing has spent most of his military career in Myanmar’s border regions, particularly in Shan and Kayah states. He has served as commander of the Triangle Regional Command in eastern Shan State and the Northeast

Command in northern Shan State, and later became chief of the Bureau of Special Operations 2, which controls the Northeastern, Eastern and Triangle regional military commands.

In his current role, he has also been involved in military operations in Kachin State and talks with the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), which has recently come closer to reaching a ceasefire agreement with the government to end a conflict that began in June 2011.

The senior general leapfrogged several four-sTar generals To geT To his presenT posiTion... surprising many.

One of the toughest challenges now facing the commander-in-chief is the Tatmadaw’s tense relations with the United Wa State Army (UWSA), Myanmar’s largest and best-equipped ethnic armed group.

Late last year, Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing met with Wa leaders in Kengtung, eastern Shan State, to tell them to stop producing and trafficking illicit drugs by 2015. But with recent reports that China has stepped up its military support for the UWSA in

an effort to increase its leverage over Naypyitaw, it will be increasingly difficult for him to exert much influence over the group.

Farther south, the commander-inchief has had much less to worry about. In January, he met with Karen National Union leaders who came to Naypyitaw to meet President U Thein Sein. The meeting was cordial, but nothing substantive was discussed, and the senior general was dressed in civilian attire when he received the Karen leaders, signaling that the meeting was intended to be seen as informal.

Although Myanmar’s armed forces and quasi-civilian government appear to be on the same page on most issues, it’s not always clear who is in charge. In Kachin State, for instance, the military continued its offensive despite repeated appeals from the president to avoid clashes unless necessary. The fighting continued to escalate until the end of last year and early this year, when helicopters gunships and jet fighters were deployed to attack the KIA stronghold of Laiza.

The trouble is that in this fragile transition period, there is confusion over the role and power of the commander-in-chief and indeed, the armed forces itself, which remains the most powerful institution in Myanmar.

Under the Constitution, the commander-in-chief possesses extensive power and a position equal to vice president. But some in the government have argued that the president should be the supreme commander-in-chief and call the shots when the country faces external or internal threats or any other crisis.

It is also not known whether the position of the defense minister (currently held by Lt-Gen Wai Lin, another Than Shwe loyalist who previously served as the Naypyitaw regional commander) is equal to that of commander-in-chief. As a result, some army insiders say that the lines of communication and the chain of command are baffling.

It is also an open secret that the Tatmadaw controls the economy. The

military-owned Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Ltd and Myanmar Economic Corporation are two of the country’s largest conglomerates, and they wield enormous influence over many key industries, including energy extraction.

Tatmadaw scholar Mary Callahan, the author of Making Enemies: War and State Building in Burma, has noted that both corporations are completely lacking in transparency. “Though they are owned by the Defense Ministry and serve as a capital fund for the military pension system, their accounts have never come under public scrutiny,” she wrote in The Journal of Democracy last year.

Since reforms began two years ago, there has been growing criticism of these military-backed business entities, particularly for their long-standing practice of confiscating land for future investment. Some sources close to Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing say that he is opposed to the practice and wants to return confiscated land to farmers. If true, he will certainly face opposition from within the armed forces and army conglomerates.

Another issue that will be of growing importance to the commander-in-chief is military relations with the West. He will likely try to develop regional cooperation with armies in the region and in the West, pulling away from Myanmar’s reliance on China. He has already asked for assistance from the West, and the US has agreed to provide military training. (The volatile situation in Arakan State, where a steady flow of immigrants from neighboring Bangladesh has caused increasing tensions, could be one area where Myanmar’s military might seek cooperation with the West.)

But some of Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing’s plans may be overly ambitious. In his speech on Armed Forces Day, he stressed the importance of building a modern and patriotic army, quoting excerpts from a speech by Gen Aung San in 1947: “The air force should have at least 500 airplanes. The army should have a strength of one million when fighting war. It must dare to respond to even the slightest provocations.”

If this is his wish list, he will have a hard time fulfilling it. If he really wants to build a professional army, however, he could begin by cleaning his own house and regaining the respect of the Myanmar people first.

Former Gen Lun Maung wants nothing more than to let bygones be bygones, taking what he knows to the grave.

Wearing an olive green vest and a longyi, the man cleaning tables at a roadside diner in southern Myanmar seems a world away from his life over the past 40 years. He told The Irrawaddy of his dramatic and unexpected fall from grace.

“I don’t want to talk about it because it’s not good for anyone concerned,” he said, referring to the main reason he was forced to leave one of Myanmar’s most powerful jobs last year.

At the height of his power under the former military regime, U Lun Maung was the military inspector general and the junta’s national auditor general. In 2011, when current President U Thein Sein came to power, he was reappointed auditor general.

But just one year later he found himself watching the television in shock, as it was announced he had been “allowed to take a rest from his duties,” which is a common official

euphemism for getting fired. “It caught me by surprise on the TV news,” U Lun Maung recalled.

Far from the halls of power, the former general now serves customers at the restaurant he owns in Bee Lin, a provincial town in southern Myanmar’s Mon State.

Many with knowledge of the matter believe he was let go because he made detailed records of corrupt officials siphoning off money from government departments, which he was to submit in his annual audit.

But he allegedly submitted an informal audit directly to Lower House Speaker U Shwe Mann, a report that is meant to be sent directly to the president. To the dismay of U Thein Sein, the report revealed massive corruption in six ministries, and was later leaked to the media.

“Despite all of my hard work, the way I did it could have had a negative impact on the country,” he told The Irrawaddy. “Even though what I did was right, it turned out to be wrong.”

U Lun Maung came from a poor

ethnic Shan family, growing up not speaking Myanmar. His parents, he says, beat him as a child when they discovered he was taking Myanmar language lessons at school, fearing he would lose his native tongue.

In the 1960s he applied to officer training at the elite Defense Services Academy at the same time as future Vice-President U Tin Aung Myint Oo. Lower House Speaker U Shwe Mann was a year above U Lun Maung at the academy and U Htay Oo, the current vice president of the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party, signed up two years later.

After their time together at the academy, U Lun Maung found he

had different ideas from U Shwe Mann and U Htay Oo, who also went on to positions of leadership in the ruling junta. “I am not in the habit of socializing with someone who is not my type,” he said.

After leaving the auditor general office, he returned with an empty wallet to be with his wife, who runs the Aung Pyae Sone restaurant in Bee Lin. He is an anomaly among retired generals in Myanmar, many of whom leave office with lucrative business interests and considerable wealth, often gained in less than ethical ways.

As the former chief government auditor, he gained knowledge of who misused government funds, but refuses

to name names. “It’s pointless to talk about it,” he says. “I don’t want to harm anyone involved.”

Meanwhile, he seems content among the dishes and diners at this modest restaurant in Mon State, occasionally barking orders at the staff in-between waiting tables and working the cash register. Waking early, he works until midnight, always wearing a worn-out olive green vest—a sign, perhaps, that he is not ready to forget the past completely.

“I have to work throughout the day. When I was a general, I had time to play golf,” U Lun Maung jokes. “Now I can’t imagine having spare time for pleasure.”

“But the life I’m living now is quite simple.”

Daw Mya Mya Sein, U Lun Maung’s wife, chimes in: “We are happy now with what we have. We can forgive anyone for what they have done to us. We regard it as retribution for bad things we did in the past.”

The restaurant business in Bee Lin is treating Lun Maung well. The restaurant gets about 500 customers each day, he says.

Is the food good?

“Yes, it’s great, because my wife prepares all of it.”

Additional reporting by May Kha

“even Though whaT i did was righT, iT Turned ouT To be wrong.”

—U Lun MaungFormer Gen Lun Maung stands behind the kitchen counter at his restaurant in Bee Lin, Mon State.

Although open conflict between Myanmar’s central government and the United Wa State Army (UWSA), the country’s largest ethnic armed group, appears unlikely in the immediate future, Naypyitaw and the UWSA may be on a collision course over the latter’s push for a separate and autonomous (but not independent) state.

That demand, stemming from unhappiness over the fact that large parts of UWSA territory are not recognized as such under Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution, is just the latest source of tension between Naypyitaw and the Wa, who worry that they could be next in line for a Tatmadaw offensive, amid ongoing clashes between Myanmar’s armed forces and other armed ethnic groups in the region.

“The relationship between the UWSA and the central government is not what it used to be,” says veteran journalist Bertil Lintner, author of several books on Myanmar, referring to the cordial relations that existed between the UWSA and Myanmar’s former military rulers in the wake of the collapse of the Burmese Communist Party (BCP) in 1989.

A mutiny that year by the BCP’s rank-and-file—mostly ethnic Wa— against their predominantly Burman leaders resulted in the formation of the UWSA, which soon signed a ceasefire that granted it a high degree of autonomy. That agreement—which freed the Tatmadaw to concentrate its

energies on containing insurgencies elsewhere—faced few serious strains until junta intelligence chief Gen Khin Nyunt was purged in 2004.

Relations have not really recovered since then, and have only deteriorated further in the two years since Myanmar made the transition to quasi-civilian rule, as a series of army offensives in the northern part of the country have brought renewed conflict to areas where, for most of the past two decades, an uneasy peace prevailed.

Although the fighting has so far most directly affected the Kachin and the Shan insurgent armies operating to the north and west of the UWSA’s main territory, centered at Panghsang on Myanmar’s border with China, clashes have come precariously close to the UWSA’s doorstep. That, says Lintner, is probably why the UWSA came to the aid of the Shan State Army—North several months ago to defend Loi Lan, a mountain that overlooks an important ferry crossing on the Thanlwin River seen as the “gateway to Panghsang.”

For the most part, however, the UWSA has avoided direct confrontation with Myanmar’s army. Even the 2009 Tatmadaw offensive against the Myanmar National Democracy Alliance Army (MNDAA) only briefly drew in the UWSA, despite the close ties between the two former BCP factions.

If the UWSA has been reluctant to go head-to-head with the Tatmadaw, it isn’t because it fears it can’t hold its own on the battlefield. As the largest group to emerge from the ashes of the

BCP, it inherited most of the former communist army’s military hardware, including heavy artillery and gun factories. It is also estimated to have at least 20,000 troops, giving it a standing army larger than that of some European countries.

Where the UWSA is vulnerable, however, is in its relations with the world beyond Myanmar’s borders. Of all the country’s ethnic insurgent armies, the UWSA is the one most closely associated with the international drug trade. In January 2005, for instance, a grand jury in Brooklyn, New York, indicted eight of the UWSA’s top leaders, including its chief Bao Youxiang, on charges of heroin and amphetamine trafficking. The US government has also made no secret of its desire to prosecute Wa leaders for their involvement in one of the world’s most notorious narcotics operations. Human rights groups have also had the UWSA in their sights for its forced mass relocation, between 1999 and 2002, of some 120,000 ethnic Wa villagers to an area along the Thai-Myanmar border—a process that also saw tens of thousands of Shan,

Akha and Lahu pushed into northern Thailand to make way for the new arrivals. According to a 2005 report by New York-based Human Rights Watch, many died of hunger and other hardships because of the move. More recent reports by aid workers who have made clandestine visits to the area suggest that not much has improved in the decade since the move was completed.

It’s unclear exactly why the UWSA inflicted this ordeal on its own people, although it’s known that Myanmar’s former military regime encouraged the move as a way to counter the Shan State

Army—South, then a non-ceasefire group that also fought the UWSA as recently as 2005. An even stronger motivating factor, however, may have been the UWSA’s desire to gain better access to its chief export market for methamphetamines, Thailand.

These days, however, the group adamantly denies that it is still in the drug business. “We, the UWSA, are wholeheartedly engaged in the fight against drug-dealing,” the group’s spokesperson, Aung Myint, recently told The Irrawaddy. “For seven years since 2005, there have been no poppy fields and no poppy plants in our region. This has finished. That’s why the world should recognize us,” he added. But while much of the world continues to vilify the UWSA, the group is not completely without friends in foreign lands. In recent months, China has stepped up its efforts to reach out to the Wa leadership, even—if a report published by Jane’s Defence Weekly in late April is correct— adding substantially to the UWSA’s arsenal with the delivery earlier this year of several mediumtransport helicopters armed with air-to-air missiles.

Although the UWSA and the Chinese embassy in Yangon both deny that the UWSA has received weapons from China, there is little doubt that Beijing—which once backed the BCP’s struggle against Myanmar’s central government—is keen to put its relationship with the UWSA on a firmer footing, for complex reasons.

One is that China has a strong interest in maintaining the status quo. “The Chinese don’t want another war on its borders,” says Lintner, noting that previous Tatmadaw offensives— against the MNDAA in 2009 and the Kachin Independence Army since June 2011—sent thousands of refugees fleeing across the border into Yunnan Province.

Adding to Beijing’s nervousness about border stability is the poor health

of UWSA leader Bao Youxiang, who has reportedly been suffering for years from a neurological illness related to eating uncooked meat. His death and the inevitable change in leadership will likely have a significant impact on how the group responds to pressure from Myanmar’s government.

But Beijing may also have other reasons for cozying up to the Wa. According to Lintner, “China, by arming the UWSA, is sending a strong message to Naypyitaw: ‘We are here, we are your neighbors, and we have the means to put pressure on you—so don’t play footsies with the Americans.’”

Lintner doubts, however, that China is interested in girding the UWSA for battle against the Tatmadaw— something that would not serve Beijing’s strategic interests in the country. “The arms shipments are meant as a deterrent, a show of force, not to be used in combat with the [Myanmar] army,” says Lintner.

While the UWSA leadership is undeniably close to China, however, those who know the Wa say they remain staunchly independent in their outlook. Aung Kyaw Zaw, the son of the late general turned BCP politburo member Kyaw Zaw, stayed with his Wa comrades for two years after his father and other Myanmar communist leaders fled into exile in China, giving him a unique insight into the thinking of the reclusive UWSA leadership.

Chinese may be the most prevalent language now spoken in the UWSAadministered area, and local rubber plantations and mining concessions may be run by Chinese businessmen, but the Wa do not see themselves as being beholden to the Chinese, says Aung Kyaw Zaw.

Instead, the Wa seem more determined than ever to stake a permanent claim to their own homeland. “We have our own people, language, traditions, culture and region. That’s why we don’t want to stay under Shan State,” says Aung Myint.

After more than two decades of de facto self-determination, the UWSA may feel that it’s ready for the real thing. Whether Naypyitaw agrees, however, is another matter. And if the Tatmadaw (which still has the ultimate say in these matters) decides it’s time to settle the issue once and for all, the UWSA may finally have a chance to put its much talked about, but rarely seen, arsenal to the test.

“The relaTionship beTween The uwsa and The cenTral governmenT is noT whaT iT used To be.”

–veteran journalist Bertil Lintner

A year after the outbreak of sectarian violence in Rakhine State, government policies seem to be strengthening divisions

By PAUL VRIEZE and HTET NAING ZAW / SITTWE

By PAUL VRIEZE and HTET NAING ZAW / SITTWE

UBaudi Amin appears apprehensive when discussing the incident that occurred when government officials, policemen and Nasaka border guards came to Thet Kal Pyin, a predominantly Rohingya village near Sittwe, on April 26.

“I lived with my wife for 20 years, I want her back,” he said quietly. “My wife did nothing, knew nothing.”

The officials had entered his neighbor’s house during a household registration procedure, but a scuffle broke out when the family refused to sign an official document identifying them as “Bengalis”.

They were promptly arrested by the angered officials, as was U Baudi Amin’s wife and a trishaw driver who was dropping her off at home.

During an interview three weeks later, U Baudi Amin, a tall, thin 50-year-old, still seems stunned by the incident. “I am too scared to ask the police about my wife,” he said.

U Baudi Amin’s family is ethnic Kaman, members of a Muslim minority who are officially recognized as Myanmar citizens. But like thousands of other Muslim households in western Myanmar’s Rakhine State, they are suffering the consequences of the deadly violence that broke out between

Rohingya Muslims and ethnic Rakhine Buddhists about one year ago.

On June 8, 2012, clashes between the groups began in Maungdaw and Buthidaung townships and quickly spread to the state capital Sittwe and surrounding areas. By October, about 140,000 people, mostly Muslims, were displaced by the violence, which left 192 people dead.

The government responded by segregating the two communities. It tightened numerous restrictions on the Muslim population, curbing their freedom of movement and access to healthcare, education and employment.

Myanmar’s Buddhist-majority government claims the harsh treatment of the estimated 800,000 Rohingyas is justified, as they are not recognized as citizens under a 1982 law. It labels them “Bengalis” and treats them as illegal immigrants from neighboring Bangladesh.

Rohingyas insist they have lived in Rakhine for many generations and

should gain citizenship. In the past year, however, government measures have consolidated the group’s statelessness, a move that is raising local tensions.

U Maung Maung, a community leader at Te Chaung, a camp near Sittwe where thousands of displaced Rohingyas live, said registration attempts had ended in arguments with officials due to the procedure’s requirement that households register as Bengali. “We will never accept being called Bengali, we are Rohingya,” he said.

Rakhine State spokesperson U Win Myaing denied that the procedure intended to record a family’s ethnicity and insisted that only displaced Muslims were interviewed “in order to provide food and aid to them.” He added that the operation had been suspended in April due to the growing resistance.

For many months now, authorities have confined some 120,000 displaced Muslims in squalid camps in the

countryside. Most used to live in Sittwe before.

At the edge of town, several lines of police and army security form a sharp demarcation line between the desperate scenes in the countryside and Sittwe’s quiet streets.

The town’s remaining Rakhine community is content with the segregation, which it sees as necessary to protect their security.

“Rakhine and Bengalis can never combine, never. They are more like Bangladeshis, their features, their dark complexion, their culture—we are different, we are Buddhists,” said U Khin Maung Gree, a central committee member of the Rakhine National Development Party (RNDP) during an interview.

Like many Rakhine, however, the influential RNDP leaders are quick to deny that they initiated or organized the violence in order to ethnically cleanse the areas, as the US-based group Human Rights Watch has alleged.

Far left: A Rohingya man holds a temporary ID card issued by the government. It mentions twice that its holder’s ethnicity and religion are “Bengali/ Islam”.

Left: Policemen stop civilians at one of the road blocks that surround Aung Mingalar, Sittwe’s last Muslim quarter and home to around 6,500 people.

U Khin Maung Gree stresses that outsiders don’t understand that the roughly 3 million Rakhine Buddhists have to defend themselves against the growing local Muslim population, and the 160 million Muslims in neighboring Bangladesh. “They need our land, they want to Muslimize our land,” he said. “So they make up a name, Rohingya, to claim they are natives of this state.”

In Sittwe, the anger is aimed at the approximately 6,500 inhabitants in the town’s last remaining Muslim quarter, Aung Mingalar, which has been sealed off by security forces.

Aung Mingalar residents said they were grateful to be under government protection, but complained that life there was extremely difficult.

“We cannot leave. Now, we are not humans, we are treated like animals on a farm. We get food and water, but have no rights and we can get no education, nothing,” U Atea, a medicine shop owner, said by phone. “I hope one day the government will arrange a better life for me.”

India has not gained much from Myanmar’s transition from military rule to a fledgling democracy. When Myanmar was ruled by a military junta and shunned by the West, India and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) were seen as alternatives to Chinese influence. But as Myanmar opens up to the outside world after decades of isolation, it is turning more to the West, especially the United States, to balance China’s growing influence, and not to India. Increasingly, Delhi is seen as a defensive power, unwilling and incapable of contesting Chinese influence in Myanmar, and not central to what has been described as the emerging “Great Game East.”

The West has long seen India, Asean and Japan as playing a key role in mitigating China’s growing stranglehold on Myanmar, a nation located at the strategic crossroads of South and Southeast Asia. In the past, US officials praised Myanmar’s more democratic neighbors for their “constructive engagement” with the former ruling junta, which helped to limit Chinese influence. Even now, many countries, including Japan, Australia and the Asean member states, would like to see India do more to offset China’s still dominant position in Myanmar.

But far from boosting its presence in its newly democratizing neighbor, India has largely withdrawn into a shell. It hasn’t even pushed Myanmar to do more to help with its security concerns along their shared border. It is happy with whatever little Myanmar has done to contain the insurgents from India’s remote northeastern states who enjoy

sanctuary in Sagaing Region, where Manipuri rebel groups are still active, and Naga and Assamese hardline factions still have bases which have yet to face any military action.

India is also doing little to stop the smuggling of weapons and narcotics from Myanmar. And, apart from completing the Tamu-Kalemyo highway—the only project India has been able to deliver on time in Myanmar—it has largely failed to implement its “Look East” policy in any meaningful, concrete way.

The Kaladan multimodal project, centering on the modernization of Sittwe Port in Rakhine State, has made only slow progress, and is, in any case, designed more to ensure access between India’s mainland and its remote northeast, rather than increase

India influence in Myanmar.

India’s ambitious Delhi-Hanoi railway corridor through Myanmar seems an even more elusive goal, as there is still no funding available to build a rail link through the border state of Manipur to the Myanmar frontier. And Delhi continues to hesitate over reopening the WWII-vintage Stillwell Road, as it tries to decide whether the move would create more problems than benefits for India.

While Myanmar’s government has sought Indian expertise in certain areas such as software development, telecoms and services, it is less interested in what India may have to offer in key

economic areas such as mining, heavy industries or infrastructure building. Nor does Myanmar’s army look to India as an alternative to China as a source of military hardware: Now that relations with the West are on the mend, the Tatmadaw can anticipate eventually having access to the world’s most advanced military technology. Development megaprojects are also beyond India’s means—for these, Myanmar is more likely to seek partners in Japan or Asean.

But India appears to have only limited interest in investing bigtime in Myanmar. It is seeking to resume its old gas pipeline project through Bangladesh to take gas to eastern India, now that it has a friendly regime in Bangladesh under Sheikh Hasina and since India’s Essar has major

stake in two blocks whose estimated reserves are believed to be exceeding those in India’s biggest recent gas find in Cauvery basin down south.

Even if it wished, India has limited resources to spare for major overseas investment which is why it backed off from the US $ 2.9 billion Padma Bridge project in Bangladesh . The Chinese and the Malaysians came up with attractive offers though Dhaka decided – perhsps to avoid offending Delhi – to do the project with its own resources.

In terms of soft power, however, India can more than hold its own, even against China. As the saying goes, Myanmars goes to China for arms and India for salvation. As the land of the Buddha, India has a special place in the hearts of Myanmar’s Buddhist faithful. Unfortunately, however, Delhi is woefully lacking in ideas on how it can effectively wield its soft power. Apart from plans to send some Buddhist relics to Myanmar, India has made no real effort to step up its cultural diplomacy as a means of forging stronger ties.

India’s private sector is also not rising to the occasion as Myanmar opens its markets to the world. There are areas where it would not face much competition, such as media, human resource development, education, healthcare, infotech, entertainment, and tourism and hotels. In all these areas, India could provide cost-effective and efficient alternatives to what’s on offer from the rest of the world. For instance, an experienced Indian media trainer would be far less expensive and much more effective than one from the West, Japan or an Asean country.

In this and other areas, however, India’s business community has not shown much initiative. Some Indian companies are getting into hotels, but not much else. Despite the huge following that Bollywood soap operas enjoy in Myanmar, India’s movie moguls have not demonstrated much interest in tapping into this market. And this is not merely a commercial loss: Media and entertainment are force-multipliers in winning hearts and minds.

For India’s political elite, Myanmar is valued chiefly for its strategic location vis-à-vis China. Efforts to strengthen India’s position in this three-way relationship have, however, been flawed. Over the last two decades, India moved away from its total support for Myanmar’s democracy movement and

cultivated ties with the Tatmadaw in a game of catch-up with China. In the process, it has lost credibility with the democracy movement, including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, and did not gain much from the Tatmadaw, either. As they say in Bengali, India lost the mango and also the sack. Now both the generals and the pro-democracy movement look to the West, and not India, as an option against China.

Myanmar is India’s only land bridge to Southeast Asia. Unless it can engage Myanmar decisively, the “Look East” thrust of Indian foreign policy will become little more than a cliché. As the world’s most populous democracy, India could do much more to help Myanmar in its democratic transition— more than just helping to run election commissions and giving advice on parliamentary practices.

What India could share most is its own rich experience in handling

Communist Party of Burma.

After General Ne Win seized power in 1962, however, Indian influence suffered as the generals saw India as the natural inspiration for the country’s pro-democratic forces. Ne Win’s expulsion of thousands of people of Indian origin strained relations with Delhi even as the general sought to make it up by sending his troops to fight the China-bound Naga and Mizo rebels. After India’s victory in the 1971 war with Pakistan (which somewhat restored the country’s pride after its humiliating defeat by China in 1962), the Myanmar junta started taking Prime Minister Indira Gandhi much more seriously. Relations suffered again under her son Rajiv Gandhi, however, due to his support for the 1988 democracy movement. At the same time, the generals continued to see India as a major regional player whose support for the democracy

ethnic minorities in its northeastern region, something that would help Myanmar enormously. India’s failures and successes in the Northeast—the challenges it has faced in dealing with insurgents and the strategies it has adopted to engage them in dialogue and finally co-opt many of them—might be more relevant for Myanmar’s new democratic leadership.

The ethnic minority problem figured at the top of the Indo-Myanmar post-colonial interaction, as India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru invited Myanmar’s first prime minister U Nu to a tour of the troubled Naga Hills. India also helped the U Nu government materially and morally to manage the first wave of ethnic insurrection after Myanmar’s independence.

At the time, Delhi’s influence was unmistakable, as U Nu looked to India as a role model during Myanmar’s first experiment with democracy. It was seen as Myanmar’s most helpful friend in the regional neighborhood, more acceptable than the colonial West. China, meanwhile, was regarded as both a problem and a hostile nation, after defeated Kuomintang troops moved into Shan State and Mao’s regime started strongly backing the

movement could be a game changer.

But when, in the early 1990s, India changed course in a desperate effort to match China’s surging influence, Myanmar’s ruling generals knew they no longer needed to worry about India. They accepted Delhi’s overtures not so much to counterbalance China as to ensure that India did not go out of its way to back the pro-democracy movement or the ethnic minorities— some of which, like the Kachin Independence Organization, had , albeit briefly, India’s covert support in the 1980s.

In the end, India never gained much influence with the military junta, but lost its credibility with the pro-democracy movement. Now, as Myanmar moves towards democracy and attempts to balance the allpervasive Chinese influence, it looks more to the West, and less to India.

Subir Bhaumik is a former BBC Correspondent and author of ‘Insurgent Crossfire’ and ‘Troubled Periphery’.

far from boosTing iTs presence in iTs newly democraTizing neighbor, india has largely wiThdrawn inTo a shell.

The skyline of Myanmar’s largest city undergoes its most rapid changes in decades, as developers scramble to cash in on the dramatic rise in demand for prime property

By SIMON ROUGHNEEN / YANGON

By SIMON ROUGHNEEN / YANGON

Condominiums under construction in downtown Yangon

Condominiums under construction in downtown Yangon

YANGON — The sweltering midday heat and choking cement dust are no hindrance as sandal-clad laborers shoulder bags of cement up five, six, seven flights of stairs, yelling as they go at slower-moving and less-weigheddown colleagues to move aside.

On the way up, they pass halffinished floors where men—and a few women—lay bricks and slap layers of plaster on half-done walls, bantering as lunch hour approaches.

Two years in the making, the 10-storey building will be ready to welcome its first tenants by the end of 2013, says site manager U Naing Win Aung. When completed, the pricy new property—complete with the obligatory gym and pool—will overlook the verdant surrounds of Yangon’s Kandawgyi Lake.

It’s a stellar location, just a mile from Shwedagon pagoda, the gilded centerpiece of worship for Myanmar’s majority Buddhists. But for now, the site is still very much a work in progress, as the builder, construction company Yadanar Myaing, works at full speed to complete the latest addition to Yangon’s rapidly changing cityscape.

But if the view from the top of the towers is spectacular, the price matches. At US $150 per square foot and with each condo measuring 1,829 square feet, that’s almost $300,000 per unit. “All 60 are sold already,” says U Naing Win Aung, his office wall covered in artist impressions of similarly lavish apartment blocks planned for elsewhere in the city.

Such eye-watering prices are fast becoming part of Yangon’s new urban legend—a story of a crumbling old colonial outpost at the center of a gold rush, with some office space rental costs exceeding prices in much more developed “first-world” cities.

In some of Yangon’s few suitable office locations—such as Sakura Tower and Centerpoint—floor space is currently on average around $60-70 per square meter. Across the road from Sakura Tower, construction company Shwe Taung Development is building a rival complex—an annex to the wellknown Traders Hotel—that will provide 14 floors of offices by the end of 2015.

The biggest foreign investment project in Myanmar over the past year, however, is the $300 million office, hotel, apartment and shopping

complex being built by a Vietnamesebacked group and going up beside the old Sedona Hotel—but that is not likely to be finished before 2017.

While property developers rush to cash in on strong demand and high prices, the dramatic increase in available office space should, in the long run, see prices drop, says property agent Daw May Htet Aung, of Power 7

Real Estate. “Hopefully the cost will come down to $50 [per square foot] or less,” she says. “As more construction finishes, there will be more office space.”

Meanwhile, the current dearth of space is slowing Myanmar’s bid to attract foreign investment and live up to the hype surrounding Asia’s latest and least developed emerging market.

“A big pharmaceutical company came to me looking for offices,” recalls Daw May Htet Aung. “But when they saw how expensive they said no, and they are postponing their business here because of that!”

That wasn’t just a one-off. “I had the same experience with two or three big companies,” she laments.

In a similar vein, Masaki Takahara, head of Japan’s overseas trade office in Yangon, says that despite his country’s newfound big-spender attitude towards Myanmar—Tokyo recently pledged 20 billion yen (around $200 million) to the proposed Thilawa industrial zone and port outside Yangon, for example—Myanmar’s poor infrastructure is holding back investment.

“For now, there is a lack of infrastructure in Myanmar, but we are hoping these issues can be solved,” he says. Japanese lending will not only help bring Thilawa online—it will also aim to boost Myanmar’s flickering electricity supply and improve roads—two key issues that need addressing to reduce costs for investors, and, perhaps, to justify the bank-accountemptying property prices in Yangon.

In the meantime, a new venture in Yangon is trying to offset the lack of office space by providing around 300 square meters of serviced offices for companies to rent.

Marc Rudolf von Rohr of Myanmar Access, a partner company in the enterprise, says that local businesses are asking about the location, citing their perceived need to have a base closer to where prospective foreign partners stay during their reconnaissance visits to Yangon.

“I was surprised at that, at first, but many Myanmar companies have their HQ farther out of the city, and they’re seeing that they need somewhere closer to the hotels and downtown so they can meet easily with foreign businessmen.”

He says, however, that he expects most of the interest to come from foreigners. “There’s blue-chip interest from Thailand and Singapore,

Foreign interest in hotel investments has accelerated this year, with some of the globe’s leading brands as well as regional players lining up to operate or build properties in Yangon.

Best Western International, one of the world’s largest hotel chains, has sealed an agreement to take over the management of the six-month-old, 189-room Green Hill Hotel in Yangon’s Tamwe Township. Marriott International, which once operated a hotel by Inya Lake, expects to seal its first agreement for a property in Myanmar in the next six months, executive Simon Cooper told Bloomberg on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum in June. Hilton Worldwide is planning a property at Centerpoint Towers.

The Singapore-listed company Amara is in talks with Youth Force International for a hotel in Dagon Township, while the French chain Accor is in talks with Max Myanmar to open a Novotel Yangon Max hotel in the Pyay Tower Complex on Pyay Road. Thailand’s Dusit Group and Dubai’s luxury chain the Jumeriah Group are also reported to be in talks over hotel properties, while the Peninsula Hotels Group has entered a non-binding deal with Yoma Strategic Holdings to develop the 100-year-old Burma Railways Building in Yangon as a hotel.

Meanwhile Vietnamese developer the Hoang Anh Gia Lai Group broke ground in June on its Hoang Anh Gia Lai Myanmar Center, a US $440 million complex which will include a five-star hotel with 480 rooms.

Interest in hotel investment is receiving a further boost from a general upswing in tourism in Southeast Asia. Rising visitor arrivals, robust trading performance and affordability have put emerging markets such as Vietnam, Cambodia and Myanmar back in the investment spotlight, Tom Oakden of Jones Lang SaSalle told HospitalityNet.

“geTTing a viable and affordable place here can be an ordeal.”

— Marc Rudolf von Rohr of Myanmar Access

companies whose names you would know.”

Since many foreign businesses are at this stage just looking at opportunities in Myanmar, temporary rented facilities often suit their needs. “People come, they have meetings, they look around, they don’t necessarily start operations so soon,” says Mr. von Rohr. “It might be like that for some time yet.”

Part of the reason companies are slow to invest in Myanmar, it seems, is not just uncertainty about the supply of essential infrastructure such as electricity, but also the difficulty of dealing with the nitty-gritty of securing even a small office space. “Getting a viable and affordable place here can be an ordeal,” says Mr. von Rohr. “You need reliable power, Internet; you need to sort out a lease. Many places are unfinished. ”

An ordeal might also be an apt way to describe what would-be renters looking for a place to call home in Yangon sometimes endure.

Emmanuel Jaquet, a Canadian who has live in Yangon for 10 months, says that “it took around 15 visits to different places” before he and his girlfriend found a worthwhile apartment within their budget.

“We wanted to share at $1,000 a month,” he says. “But my girlfriend saw so many places that were just not

finished, were dirty, had no facilities, but people were charging these crazy prices.”

The couple’s househunting adventures involved some encounters with some unorthodox interior design. “We saw one place that had a shower in the kitchen,” says Mr. Jaquet.

After finally finding a suitable place, Mr. Jaquet says the couple’s troubles continued. “The landlord was happy to take our year’s rent upfront, but when something needed fixing, we had to wait for weeks. In the end, we just decided to get it fixed ourselves and sent the landlord the bill.”

Such stories are legion among foreign tenants coming to Yangon, the numbers of whom have “picked up a lot” over the past year, according to Daw May Htet Aung.

It is standard practice in Yangon for landlords to want a full year’s rent upfront, with little chance of refund if for whatever reason if the person has to leave the country. “Foreigners are not used to the Myanmar way,” says Daw May Htet Aung.

As for the owners, she sighs that for the most part “they are not interested in the business of being a landlord— they just want all the money only.”

Above: Yangon’s landmark Shwedagon Pagoda can be seen in the distance from a Yadanar Myaing construction site on the Kandawgyi ring road. Right: At work at the new Novotel Hotel in Yangon“foreigners are noT used To The myanmar way.”

— Yangon property agent Daw May Htet Aung

Anew master plan for Yangon envisages, among other things, a second Central Business District, green zones, 10 outer hubs, four outer “new town cores” and development of the riverfront in the downtown area.

Yangon’s population is expected to almost double to 10 million by 2040 in the plan unveiled in May by the Yangon City Development Committee and the government’s Division of Urban Planning. But the distance between the envisioned modern “mega city” and Yangon’s current crumbling infrastructure is immense, with major investment needed in power supply, transportation, waste disposal, and water and drainage.

Water supply looks set to get an early boost, with a 1.9 billion yen (US $20 million) project for the “urgent improvement” of water supply in Yangon city recently announced by Japan and the Ministry of National Planning and Economic Development.

The water supply system suffers from water stoppages, low feed water pressure and 50 percent water leakage due the aging of the system and inappropriate management due to budget constraints, according to a statement from the Japanese embassy.

It said that only two of four pumps are working at the Nyaunghnapin Water Treatment Plant (Phase 1) Pumping Station, which supplies approximately 40 percent of the city’s supply. The project will renovate the plant and water pipes through the city.

Drinking water quality in Yangon also needs to be addressed, according to a study by Hiroshi Sakai and others published recently in The Scientific World Journal. The researchers studied drinking water in public pots, non-piped taps, and bottled water. They found that quality was lowest in pots and non-piped tap waters.

One bottled water sample would not meet Japanese standards for drinking water, the study found.

The researchers said that river and lake water around Yangon would only be suitable for drinking “after advanced treatment.”

Her company plans a sort of clearthe-air event sometime this summer, “to try to bring the owner and the tenant together.” She doesn’t know if this will lead to landlords adopting the more standard practice of charging month-by-month and requiring just one month’s notice of termination, but she acknowledges that “we need to improve how the market works in our country.”

For now, catering to the needs of foreigners, under whatever terms, is lucrative for those in the right place. The average apartment rental for foreigners coming to Yangon, says Daw May Htet Aung, is between $2,000 and $4,000 per month. However, she adds, some places go for as much as $20,000 per month.

That’s right—$20,000, to rent an apartment. “Yes, big company, petrol company, they can pay this for their staff,” says Daw May Htet Aung.

While it is still far from certain whether an increase in the number of available spaces will see such prices fall, what is clear is that Yangon badly needs more office space and more accommodation—both apartments for those staying for several months or longer, and hotel rooms for the growing number of tourists visiting the country.

But the drive to develop Yangon— which officials say could become a “mega city” of 10 million people or more by mid-century—threatens to undermine the unique atmosphere of a city that still has a sense of history, in a region where most big cities have succumbed to poor urban planning and the replacement of older, architecturally significant buildings by glassy malls and ugly high-rises.

The Yangon Heritage Trust (YHT) is at the forefront of efforts to save as many of the city’s moldering old colonial edifices as possible.

YHT Director Daw Moe Moe Lwin says that her group does not want to impede much-needed construction Parkland shof new housing and business complexes, but fears that Yangon could “lose its soul” if the drive to develop leads to destruction of the array of Victorian and Edwardian neoclassical buildings from which Britain ran this corner of its South Asian empire.

Though some discern that the property boom is starting to level out, asking prices at the top end of the market remain high. A few examples, to rent and to buy, are shown here.

For Rent: Penthouse in Yangon

A “luxury penthouse with roof garden” at an undisclosed Yangon location has been advertised in a Colliers real estate brokers’ email newsletter at a rental price of US $15,000 per month.

The apartment has three master bedrooms plus a study, is described as “ideal for entertaining” and is fully furnished to international standard. It also has its own private lift.

For Rent: Large House

A three-storey, eight-bedroom house, with a floor space of 650 sqm, is for rent for $10,500 a month in the Golden Valley area in Bahan Township. It has seven master bedrooms, two other bedrooms, a dining room, eight washrooms and two kitchens. There is a garden and pond.

For Sale: Duplex Penthouse by Inya Lake