The Hotel @ Tharabar Gate is located in the most unique archaeological site of Southeast Asia, the ancient capital of the Burmese empire, Old Bagan.

Surrounded by more than 4,000 ancient temples and pagodas, you will be enchanted by the breathtaking views. The Hotel @ Tharabar Gate is within 5 minutes walking distance of the spectacular Ananda Temple, known as ‘The Jewel of Bagan.’

The hotel offers 83 luxury rooms, including 4 suites. Every room is decorated with teak floors and typical Burmese furniture.

All rooms are fully air-conditioned and feature an IDD telephone line, satellite television, safety deposit box, mini-bar and a private garden. Each room comes with a high ceiling and different handpainted wall paintings, which are all copies of original temple paintings of the Bagan period. Internet and Wi-Fi is available in the lobby.

The hotel offers two dining choices: in the tropical garden and at the semi-open main restaurant. The restaurant accommodates 100 diners and a further 150 around the swimming pool and garden. The restaurant is well-known for its open-air fine dining, including traditional Myanmar food, European food and Asian cuisine. The hotel also features a pool-side bar to relax with a cool cocktail or drinks of your choice. Furthermore the hotel offers the option to order in-room dining at any time of the day or night.

For relaxation after a day of sightseeing we invite you to experience our spa with signature treatments from Myanmar and Thailand.

The 24-hour butler service will arrange the following for you: transport, guides, sightseeing tours, airline reservations, or a balloon ride with our partner, ” Balloons Over Bagan.” The hotel is a 15 minutes drive from Nyaung Oo Airport and most of the major sightseeing places for which Bagan is famous. We can also offer a sunset boat trip with snacks and drinks on board to watch the beautiful sunset over the Ayeyarwady, as well as excursions to Mount Popa (Taung Kalat).

Whatever you would like to do during your time in Bagan, we are here to make your visit an unforgettable one.

YANGON SALES & RESERVATION OFFICE

Room 2H, 1st Floor, Nawarat Condo, Sa Mon Street, 22/24, Pyay East Qtr, Dagon Township, Yangon, Myanmar.

Tel: (+95-1) 377956 / 376568, 09-450054234

Fax: (+95-1) 377830

THE HOTEL @ THARABAR GATE

Near Tharabar Gate, Old Bagan.

Tel: (+9561) 60037 / 60042 / 60043

Fax: (+9161) 60044

Email: smm@hoteltharabarbagan.com.mm reservation@hoteltharabarbagan.com.mm

Web: www.tharabargate.com www.hoteltharabarbagan.com

The Irrawaddy magazine has covered Myanmar, its neighbors and Southeast Asia since 1993.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Aung Zaw

EDITOR (English Edition): Kyaw Zwa Moe

ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Sandy Barron

COPY DESK: Neil Lawrence, Paul Vrieze, Samantha Michaels, Andrew D. Kaspar, Simon Lewis

CONTRIBUTORS to this issue: Aung Zaw; Kyaw Zwa Moe; Simon Roughneen; Kyaw Phyo Tha; Samantha Michaels; Virginia Henderson; Bertil Lintner; Nyein Nyein; Kyaw Hsu Mon; Grace Harrison; Jacques Maudy; Emilie Roell.

PHOTOGRAPHERS: JPaing; Steve Tickner; Sai Zaw; Teza Hlaing

LAYOUT DESIGNER: Banjong Banriankit

SENIOR MANAGER : Win Thu (Regional Office)

MANAGER: Phyo Thu Htet (Yangon Bureau)

REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS MAILING ADDRESS: The Irrawaddy, P.O. Box 242, CMU Post Office, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

YANGON BUREAU : No. 197, 2nd Floor, 32nd Street (Upper Block), Pabedan Township, Yangon, Myanmar. TEL: 01 388521, 01 389762

EMAIL: editors@irrawaddy.org

SALES&ADVERTISING: advertising@irrawaddy.org

SUBSCRIPTIONS: subscriptions@irrawaddy.org

PRINTER: Chotana Printing (Chiang Mai, Thailand)

PUBLISHER LICENSE : 13215047701213

6

8

14

Myanmar: A Nation Living a Lie

REGIONAL

50

Vietnam Bets on Luring High Rollers

By relaxing anti-gambling laws, Vietnam’s government could give the country’s economy a US$3 billion boost

LIFESTYLE

52

Travel: A Day in the Dark

The Pindaya Caves in Shan State are the site of a six-day festival this month

54

Travel: Soak Up the Sea

A vast expanse of natural beauty and campfire dinners are among the charms of Ngwe Saung beach

56

Destinations: A Gateway-in-Waiting

A motorbike trip from India into Myanmar yields some surprises – mostly on the part of border officials

60

Food: Shan Yoe Yar Raises the Bar

A recent addition to Yangon’s restaurant scene sets a new standard for Shan cuisine

62

Society: A Walk in the Park

The successful revival of Maha Bandoola Garden park provides an inspiring example of citizen-friendly green space

64

Music: After Split, Me N Ma Girls

Power On

Remaining girls visit USA to record first album

16 |

Development: Myanmar Tourism’s ‘Crown Jewel’ Feels Strains of Growth

Bagan struggles to balance competing demands as visitors arrive in ever larger numbers

20 | Culture: Face to Face with the Tattooed Women of Chin

A journey to the remote villages of Chin State reveals faces inked in tradition but struggling against the hardships of isolation, poverty and government neglect

24 |

Society: The Safe Sex Talk, Myanmar Style

In a country where talking about intimacy is taboo, efforts are under way to develop a better system for educating youths about safe sex

28 | Society: School Hits the Road for Teashop Boys

A classroom on wheels offers poor children a chance to catch up on years of missed schooling

30 | Politics: A Federal Model that Fits

There are many forms of federalism in the world, but only one really matches Myanmar’s needs

32 | COVER For the Love of the Lake

Inle Lake is facing threats, but momentum is growing to preserve its natural beauty and cultural integrity

38 | Securities: Stock Market on Track, but Hurdles Remain

Much remains to be done before Myanmar launches Asia’s newest stock exchange in late 2015

46 |

42 |

Interview: A Tale of Retail Success

Money: Cleanliness: Not Always a Blessing? Money-changers’ insistence on crisp dollar bills mars the country’s image

48 | Roundup: Army Land Theft a Thing of the Past, Claims Govt

Relations between Myanmar and France date back to the early 18th century, but ties were largely on hold in recent decades due to Western sanctions on Myanmar’s former military regime. Since the current government introduced reforms after coming to power in 2011, however, the two countries have moved quickly to increase their engagement. The Irrawaddy recently spoke with France’s ambassador to Myanmar, Thierry Mathou, about his country’s growing role in Myanmar’s ongoing political and economic transition.

has always been keen to promote the principle and values of CSR [corporate social responsibility] that should become the motto of all investors in Myanmar.

What French investment has come to Myanmar since 2011, and what angles are prospective investors looking at now?

How would you describe the relationship between France and Myanmar today?

France-Myanmar relations are growing better every day. The number of French citizens living in Myanmar is booming: It’s now 65 percent more than last year. More and more companies are settling down here. French citizens are the most numerous European tourists to visit the country. President U Thein Sein’s visit to Paris last year, the first ever of a Myanmar head of state to France, was a milestone in the history of intergovernmental exchanges between our two countries. In 2012 we were honored to receive Daw Aung San Suu Kyi for her first trip overseas since her release from house arrest. Many other bilateral visits are in the pipeline. France is eager to engage with Myanmar in a very positive way in sectors such as economy, culture, education and health, while further promoting democracy and human rights remains very high on our agenda.

The release of political prisoners has been a condition for many Western governments to boost ties with Myanmar. President U Thein Sein promised to release all political prisoners by the end of 2013, but activists say dozens remain behind bars. What’s your take on the

situation? Will this affect French engagement here?

Obviously this is still an issue. Hundreds of political prisoners have been released since 2011. We have acknowledged and praised this unprecedented trend. Forming the Review Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners (RCRPP) was also a significant step. Yet all remaining political prisoners have to be released and arbitrary arrests have to be ended. Freedom of conscience must have no boundary.

The French oil giant Total faced some criticism from the international community for its work in Myanmar during the former military regime. Did the French government ever consider trying to persuade the company to divest?

Oil and gas companies are engaged in long-term strategies that involve commitments over several decades that are different from governments’ approaches. In the case of Total, the implementation of the Code of Conduct has always been very important for the French government. I notice that Total’s Socio-Economic Program is now described as an example by many stakeholders, both in Myanmar and abroad. In that respect France

The number of French companies coming to Myanmar is increasing rapidly. Large companies like Accor, Alstom, Bouygues, Lafarge, L’Oreal, Schneider Electric, Technip and many others are already in place. SMEs [small and medium enterprises] are also studying the market. Others are to come. The French-Myanmar Business Association, which used to be the oldest Western business association in this country, will soon become a full-fledged chamber of commerce under the name of the FMCCI [French Myanmar Chamber of Commerce and Industry]. Yet like others, French companies need improved macroeconomic and sectorial policies, better legal stability and more transparency, to invest in the long term on a larger scale.

Myanmar Posts and Telecommunications (MPT) has held partnership talks with several international telecoms firms, including France Telecom. Can you tell us more about that?

Orange (France Telecom) is a worldclass telecoms player which has unique experience in the transformation of incumbents worldwide in countries that face similar challenges as Myanmar. For that reason it has proposed a partnership to MPT that would enhance its strategic and business development which is crucial for MPT to face its new competitors. We have many reasons to think that Orange’s proposal is by far the best for MPT. The decision is up to the Myanmar government.

France co-chairs the sectoral working group in Myanmar on women’s empowerment. Over the past year there have been

continuing reports of rape in conflict zones, and women have remained largely sidelined during the peace negotiation process. What steps are being taken to address these issues?

France has chosen women’s empowerment as one of its priorities in Myanmar because it is a very concrete way to promote democracy and human rights. The Women’s Forum we organized in Yangon last December was an occasion to highlight the role of women in the peace-building equation. It showed that in a 2013 review of major peace processes around the world, less than 9 percent of negotiators were women. Myanmar is certainly not an exception. I was pleased to notice that thanks to the consistent advocacy of NGOs, the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) has decided that one-third of its central committee members would be women. This type of decision has to be amplified and implemented in all organizations, including government. But men’s resistance is not always the problem. Women often have to be convinced. We will pursue our gender advocacy as we will defend women’s rights wherever they are in danger.

In the coming year, what can the Myanmar government do to encourage more French engagement?

We understand that genuine democracy cannot be created overnight. In that respect we acknowledge the step-bystep approach implemented by the government. But new major steps await Myanmar in 2014. As far as the peace process is concerned, we are looking forward to the long-awaited political dialogue which has to start as soon as the national cease-fire agreement is signed with clear and ambitious objectives that respect the rights of ethnic groups within the framework of national unity.

The ability of Myanmar to amend its Constitution in a way that demonstrates its willingness to further engage on the path of democracy and to implement much-needed changes in the interests of the people will also be closely watched. Any other approach would come as a disappointment both at home and abroad. Creating unnecessary delays and keeping restrictive clauses would be a bad signal.

Last but not least, we are looking forward to knowing the content of the Comprehensive Strategy and Action Plan for Rakhine State that the government has agreed to share with international partners, so that a solution can be found to the current crisis and we can offer our support.

France has signed an agreement with Myanmar to help strengthen freedom of expression in the country by offering technical advice on media laws. How free

is the Myanmar press today, and what is your opinion of draft media laws currently being considered by Parliament, including the printing and publishing registration bill?

Freedom of expression is coming a long way in Myanmar. Much progress has been made during the last three years, but many challenges lie ahead. France has a very simple stand as far as media laws are concerned: Always protect rights, never restrain liberty. Training is also essential in a world where journalists have to be responsible and independent actors of civil society. This is why France has taken the initiative with other partners to initiate the first School of Journalism in Myanmar that will soon open in Yangon.

When President U Thein Sein met President Francois Hollande in July last year, Mr. Hollande reportedly expressed concerns over the treatment of ethnic and religious minorities. How would you rate the Myanmar government on its response to reports of violence against Muslims since then?

Growing violence between religious minorities is a serious concern, especially in Rakhine State, where fear is on both sides. This situation should be addressed without delay through a “local peace process.” First, bring people around the table and stop violence. Then discuss political issues, with no taboos, with the objective to bring long-lasting peace, stability and development in Rakhine while addressing concerns and respecting rights of both Buddhist and Muslim communities. Otherwise the current crisis could become a major problem for the overall transition process in Myanmar.

PHOTO: JPAING / THE IRRAWADDYPeople in Myanmar expect a bumpy ride in 2014 as the “big four”— Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, U Thein Sein, U Shwe Mann and Commander-in-Chief Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing—are likely to compete and divide the nation.

The armed forces chief’s political ambitions remain a mystery. The falling-out between Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and U Thein Sein is seen as a bad omen. Ambitious Union Speaker U Shwe Mann is seeking to amend the controversial 2008 Constitution.

–U Thein Myint, a trustee of the Maha Wizaya Pagoda, built by former dictator Gen. Ne Win in 1980, in the shadow of Yangon’s revered Shwedagon Pagoda

–U Ohn Myint, the minister of livestock, fisheries and rural development and a former general, in an angry exchange with villagers that was captured on video

“I am Gen. Ohn Myint and I’ll dare to slap anyone in the face.”

“We earn less than US$10 per month in donations from occasional foreign visitors.”

“Frankly…it was clear that there are some who are committed to a reform process, and others who would like to shut it down.”

–Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, talking to reporters after meeting senior government officials in Naypyitaw

Myanmar’s Ministry of Information (MOI) has started denying requests for three- to six-month journalist visas for foreign passport holders who work at formerly exiled media groups, in a move seen by

some as part of a government effort to rein in the country’s media. “I only got 28 days,” said U Toe Zaw Latt, an Australian passport holder who works as the Yangon bureau chief for the Democratic Voice

of Burma (DVB). Editors from The Irrawaddy were also affected by the new restrictions. Foreign and domestic media observers say that the MOI is growing increasingly wary of critical reporting in the wake of a relaxation of draconian press rules since the country started opening up in 2011. In early February, four reporters and two executives from the Yangon-based Unity journal were arrested in connection with a report on an alleged chemical weapons factory in central Myanmar. The government denied the allegations, but said the arrests were valid under the 1923 Official Secrets Act.

Around 200 people who had built houses on militaryowned land in the popular beach area of Chaung Tha in Ayeyarwady Region were sued for trespassing in late January. The local residents allegedly built fences and houses on about 34 acres (13 hectares) of land in Chaung Tha that was transferred to the army about 18 years ago. Sources close to some of the defendants said that 209 people had been charged

with trespassing by the army’s Southwest Regional Command, in a case that has been under investigation since 2012.

The Myanmar government is preparing to submit three new wetlands areas for recognition under the Ramsar Convention, which protects wetlands of international importance. The 100-square-kilometer Moeyingyi Wetland Wildlife Sanctuary in Bago Region is currently listed as a Ramsar Site, but Minister for Environmental Conservation and Forestry U Win Tun said that Myanmar was surveying Indawgyi Wildlife Sanctuary in Kachin State, the Meinmahla Kyun Wildlife Sanctuary in Ayeyarwady Region and the Gulf of Mottama (Martaban) so

that they could also be considered for inclusion on the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance. He made the remarks on Feb. 2, World Wetlands Day.

political demands around the country and warned these actions could lead to unrest. “Some discussions can lead to disagreements. If the disagreements cannot be solved in Parliament, it will spread to outside of the Parliament [and] there can be demands, riots and violence by groups of people,” the president wrote. “When these cases happen, we will face pressure from local and foreign media on our government.”

In a top secret document leaked to The Irrawaddy, President U Thein Sein warned his government that the country could face mass protests and violence as calls to amend the military-drafted 2008 Constitution grow stronger. It said that activists are mobilizing support for their

Police in Malaysia said they were investigating the attempted assassination of two ethnic Rakhine political leaders from Myanmar after shots were fired at them in Kuala Lumpur on Feb. 5. Dr. Aye Maung and U Aye Thor Aung of the Arakan National Party were just leaving a shopping center in

A government commission set up to investigate violence in Rakhine State in mid-January will try to establish the “root cause” of the death of a policeman said to have been killed by a Rohingya mob on Jan. 13, but did not say if it would address allegations made by the United Nations that almost 50 Rohingyas were killed in related violence. The commission, which was announced in state media on Feb. 7, was expected to report its findings to President U Thein Sein by the end of the month. An earlier investigation by the

Myanmar National Human Rights Commission found no evidence that alleged

massacres of Rohingyas in the village of Du Chee Yar Tan took place.

the Malaysian capital when the incident occurred. They both escaped unharmed after two gunmen on a motorcycle opened fire on them. At a press conference held in Yangon two days later, Dr. Aye Maung said the attack might have been related to the situation in Rakhine State, where tensions have been high since the outbreak of communal violence between Rakhine Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims in June 2012. Several attacks on Myanmar nationals living in Malaysia have been reported since the violence in Rakhine State began.

Myanmar’s largest ethnic armed group, the United Wa State Army (UWSA), has selected 30 soldiers to receive pilot training in China, according to sources who visited the group’s headquarters on the Myanmar-China border. Senior military officers from two ethnic armed groups told The Irrawaddy that UWSA officials informed them of the plan during a visit to their headquarters at Panghsang in Shan State in January. In April of last year, Jane’s Intelligence Review reported that China had delivered several Mil Mi-17 ‘Hip’ medium-transport helicopters armed with TY90 air-to-air missiles to the UWSA. Both China and the UWSA have denied the report. The UWSA is the largest ethnic rebel group in Myanmar, with an estimated 25,000 soldiers. It signed a ceasefire agreement with the government in late 2011.

PHOTO: MYANMAR MINISTRY OF INFORMATION A fire in the western part of the village of Du Chee Yar Tan in Rakhine State destroyed 16 homes on Jan. 28. PHOTO: REUTERS

A Buddhist monk looks at a portrait of U Thant in the Yangon home of the former United Nations secretary-general (19611971) on Feb. 2, 2014, during celebrations held to commemorate the birth and legacy of one of Myanmar’s most respected statesmen.

in 1962. At the time, socialism was a popular ideology in many parts of the world, so he simply adopted it as a way of legitimizing his military dictatorship. Sadly, he fooled even real socialists—or rather, they fooled themselves—into accepting his bizarre brand of misrule as a serious attempt to turn Myanmar into a socialist state.

After Gen. Ne Win was forced to step down in 1988—and a handpicked set of generals quickly stepped in to fill his shoes—the new regime continued to rule through a combination of brute force and brazen mendacity. Army officers who slaughtered civilians were called heroes, and dissidents were labeled terrorists and thrown in prison. Did anyone really believe this? Probably not. In fact, one of the few good things you can say about the post-1988 regime is that its lies were so blatant that the general public wasn’t even tempted to be persuaded by them. But the generals were so insistent on their version of history and their role as “saviors” of the nation that most people simply held their tongues rather than argue with them and risk imprisonment or worse.

The people of Myanmar live in a complex society where right and wrong are often impossible to tell apart. We are so accustomed to being lied to that we no longer know what to believe. Perhaps people in other countries also feel this way sometimes; but in Myanmar, there is an almost palpable sense that this is a society mummified by a web of lies.

The truly disturbing part of this is that sometimes we can’t seem to avoid being complicit in these lies. Whether we consciously accept falsehoods or simply fail to challenge them, we contribute to the way that we encase ourselves and others in dangerous delusions.

A good example of this was when Gen. Ne Win introduced his “Burmese Way to Socialism” after seizing power

These days, the situation is more complicated. Now everybody professes to want democracy, even the generals who spent half a century crushing it. Late last year, for example, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing, was quoted by Radio Free Asia as saying that he wanted “real, disciplined democracy.” But you really have to wonder if the word “democracy” means the same thing to him as it does to all those who have struggled for decades to achieve it, and for the millions in Myanmar who have lived their entire lives deprived of even the most fundamental rights.

We are supposed to believe that Myanmar today is a country reborn, that its rulers have seen the light and are now intent on introducing democratic reforms. But even though there have been undeniable changes since a “civilian” government of exgenerals assumed power in 2011, how can we be sure that those who still

have their hands firmly planted on the steering wheel are really taking the country in the right direction?

The truth is that the current “transition” in Myanmar is built upon a foundation of lies—lies that the country’s people were forced to accept as the only way out of a desperate situation.

The first of these lies was perpetrated a week after Myanmar experienced the worst natural disaster in its long history. In a rigged referendum held on May 10, 2008, a nation traumatized by Cyclone Nargis supposedly voted overwhelmingly in favor of a militarydrafted constitution that enshrines a leading role for the armed forces in political affairs.

Then, in November 2010, the nation voted again, this time for a new government. Unsurprisingly, the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) won by a landslide.

At that stage, no one had any reason to believe that anything had really changed. But after President U Thein Sein assumed office the following year, he started sending signals, such as releasing political prisoners and relaxing controls over the media, to indicate that he was a new kind of leader, and that the bad old days of arbitrary military were truly over.

Eventually, even Daw Aung san Suu Kyi, whose National League for Democracy had boycotted the 2010 election, was sufficiently convinced of the president’s sincerity that she decided to contest in by-elections in 2012, even though her party only stood to win a tiny handful of seats in the overwhelmingly USDP- and militarydominated Parliament.

Now, nearly two years later, we find ourselves in the peculiar situation of half-accepting a political system that we know is no more than an extension of the former illegitimate regime. Even journalists who once fought for media freedom are now happy to buy into the Ministry of Information’s efforts to treat the press as a “public service” that needs to be regulated.

On the subject of constitutional

change, we no longer dare to question the legitimacy of the 2008 Constitution itself. Instead, we call for amendments to specific clauses, such as the one that makes Daw Aung San Suu Kyi ineligible for the presidency because she has two foreign-born sons.

Some in the government have lent a sympathetic ear to calls for changes to the Constitution, although so far none have been willing to do more than pay lip service to the need for reform. Meanwhile, the USDP has ominously warned that any attempt to tamper with the charter could result in “bad consequences.” We all know what that means: in a worst-case scenario, a return to outright military rule.

Because we dread a reversal of the modest progress of the past few

of military rule, which has left some minds so scarred that they can no longer conceive of a political system that doesn’t have a tyrant at its center.

But the people of Myanmar cannot allow themselves to be influenced by such weak reasoning, which is no more than a cover for cowardice. We all know the fear of speaking our minds in a country where that has long been a crime, but it is past time that we stopped being afraid of the shadows of a regime that now feels a need to hide behind a veil of democratic respectability.

We know what we want: a democratic constitution, free and fair elections, and a government that is truly chosen by the people. What we don’t know is how or whether we

years, we are afraid to boldly speak out for more meaningful changes to the political system. To conceal their own timidity, some intellectuals have even tried to rationalize acceptance of the status quo by arguing that letting the supposed “moderates” among the exgenerals hold on to power indefinitely is the best way to ensure that the country doesn’t fall back into the hands of the hardliners.

It’s difficult to know what to make of such an absurd argument. Perhaps the most generous thing we can say is that it is a product of half a century

can achieve these things. And in our self-doubt, we may be tempted to do what we have always done: accept lies as truth and simply hope that we will one day enjoy the freedoms that other countries take for granted.

If that is the approach we choose to take, then we can always take comfort in one thought: Even if we don’t get the government that we want, we will at least have the government we deserve.

Kyaw Zwa Moe is the editor of the English-language edition of The Irrawaddy.With several dozen A4sized paintings weighed down with stones on the cobbled forecourt of the Shwegu Gyi pagoda, artist U Aung Aung offers visitors to the shrine an affordable souvenir of their visit—a commissioned painting of the temple for a fee of 10,000 kyat or less.

He and brother U Soe Lwin run an impromptu gallery and art shop outside one of the bigger temples making up Bagan’s panoply of around 2,500 mostly red- and brown-bricked pagodas—a renowned tourist draw

pulling in around 200,000 visitors in 2013, up from 160,000 the year before.

The brush-wielding brothers depend on the tourist season, which runs from around mid-November to mid-February, with numbers dropping sharply around March or April when temperatures in Bagan, situated on a river bend in Myanmar’s parched dry zone, hit toward 40°C (104°F).

“Some days five, some days 10, some days maybe one or two,” U Aung Aung said, discussing how many paintings the siblings sell each day.

But the presence of the brothers—

along with other hawkers around this and other landmark temples in Bagan— is a reminder that visiting Bagan has its downsides, for some.

Women selling lacquerware souvenirs and men propped up on parked bicycles shout entreaties at passersby, or, unsolicited, provide tourguide services around the temples, after which the expectation is that the visitor will repay their expertise by purchasing some of their wares.

Unwrapping a palm-sized sheet of white paper, one man who gave his name as “U Tun Tun” whispered, “I

have orange sapphire, ruby, jade. The ruby is for US$120.”

Some might say such in-yourface bartering is part of the charm of visiting a long-closed former military dictatorship.

But Dr. Donald Stadtner, author of Sacred Sites of Burma, a book about Myanmar’s religious buildings and locations, is among those who are put off by the hawkers around Bagan’s temples. The buildings themselves—Bagan’s main attraction—are compromised, Mr. Stadtner feels, by shoddy renovations carried out during Myanmar’s period of

military rule, partly to replace pagodas damaged in a 1975 earthquake, and partly to modernize the ruins in a display of piety.

“Thousands of temples have been restored at Bagan but with little attention to historical accuracy. [Changes are] based far too much on conjecture, and temples and stupas no longer preserve their original appearance,” he said.

Visitor numbers are increasing, and if the government’s hopes of attracting 7 million tourists a year by 2020—more than three times the 2 million foreign visitors who came during 2013—come to fruition, Bagan will likely see around 1 million visitors a year within that time.

As things stand, the area’s three small towns—Old Bagan, New Bagan and Nyaung-U—might struggle to cope with such an influx.

Brett Melzer, co-founder of Balloons Over Bagan, whose hot-air balloons give tourists a chance to see the temple-studded plain below in all its dusty, ethereal glory, reckons tourism development in Bagan should not focus on just numbers of visitors.

“As it currently stands, there isn’t the capacity to deal with a greater influx,” he said. Describing the region as “a crown jewel for Myanmar,” he suggested that in future Bagan tourism focus “on quality rather than just

growth.”

Land prices are going up, as demand for sites to build hotels, shops and restaurants grows in tandem with the tourism upsurge and in anticipation of lucrative future yields.

U Hla Min, manager of the Seven Diamond travel agency branch in Nyaung-U, said that business has gone up “by around 60 percent” since 2010, the year before Myanmar’s government began a series of reforms that have facilitated increased tourist arrivals.

But, he says, hotels are too expensive, something he fears will put visitors off, just as much as Bagan’s flawed renovations or pushy hawkers.

“Minimum is 50, 60 dollars a night,” he says, putting the costs down to land prices. “One square meter is five lakhs [500,000 kyat] in Old Bagan, for Nyaung-U maybe a bit less,” he said.

Building in the region requires a permit, meant to ensure that the proposed new structure does not add to the ill-advised eyesores built during military rule—termed “blitzkrieg archaeology” by renowned Myanmar historian U Than Tun.

The upshot of putting hotels and golf courses in among all those temples was that a bid to have Bagan listed as a Unesco World Heritage Site fell flat, though there is a chance that it could yet receive the prestige-laden accolade if another application is made.

Elizabeth Moore, professor of Southeast Asian art and archaeology at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, believes that Bagan is worth putting forward again for this toptier recognition of its world-class cultural status.

“It is unique, perhaps complements Angkor, but is a classic Buddhist royal center of learning. The dispersed villages and royal enceinte make an ancient and living cultural landscape in my view,” she told The Irrawaddy.

But with elections coming up in 2015, winning Unesco’s imprimatur is probably less of a priority for the government than speeding up the business side of Bagan’s tourism development. Jobs are still scarce in what remains one of Asia’s poorest countries, with the unemployment rate estimated at 37 percent, so tourist draws such as Bagan have to be brought into the government’s job-creation thinking.

But U Tun Aung, the general manager of the Riverside Hotel, which sits on a hill overlooking the Ayeyarwady River and a busy dock where boats take piles of the renowned local lacquerware to be sold in Mandalay, said that there is a tension between those who focus on preserving Bagan’s archaeological purity and others whose first priority is business.

“The Culture Ministry says it wants to protect the zone, but the hotels and tourism sector wants to build the hotels,” he said.

He added that people in the hotel business understand the need to preserve the look of the region, but at the same time don’t like the delays imposed by the government.

“We would like to follow the regulations, but too much is a waste of time, as we need to move quickly,” he said.

A journey to the remote villages of Chin State reveals faces inked in tradition but

By JACQUES MAUDY / KANPETLET AND MINDAT TOWNSHIPS, Chin State

By JACQUES MAUDY / KANPETLET AND MINDAT TOWNSHIPS, Chin State

Iwas told before setting off for Chin State that it was one of the poorest and most isolated regions of Myanmar. I thought I was prepared for this, but as is often the case, facile descriptions failed to do justice to the reality on the ground.

My purpose was to document the tattoo-faced women of Chin. The women we met belonged to six tribes in the southeast of the state, concentrated around the townships of Mindat and Kanpetlet. There are some 12 Chin tribes that once practiced facial tattooing, spread between northern

Rakhine State and southeastern Chin State. The tattooing survived long after the Myanmar government officially forbade it in 1960. Traditional tattooists were still active until the mid-1990s, and I met one 30-year-old woman whose face was inked just 15 years ago.

Access to Mindat from Bagan in Mandalay Division is easier than reaching Kanpetlet. For either destination, a four-wheel drive vehicle is a must. Expect hours of bumpy dirt tracks, river crossings

Not far into the journey, you get the sense that Chin State has been forgotten by the central government. Others say it is a voluntary isolation, until recently at least. Chin State is predominantly Christian but also strongly animist, and many here complain of religious discrimination from Naypyitaw and its mostly Buddhist leaders.

A road is under construction from Mount Victoria and nearby Kanpetlet to Seikphyu on the Ayeyarwady River, but it will be at least three years before you can cruise with ease up to Mount Victoria (Nat Ma Taung) National Park, which hosts Chin State’s tallest mountain. Today it is a harrowing four hours along a dusty and rock-strewn route that hardly qualifies as a road.

But at least, many locals say, things appear to be moving in the right direction. The absence of roads is the most immediate complaint from locals, along with a lack of medical assistance.

Muun, Daai and Makaan tribeswomen are easily spotted in Mindat and the villages around it. Muun women display a distinctive P-shaped pattern on their cheeks and a Y symbol on their foreheads that mirrors an animist totem carved and planted in their villages. Faithful to their animist traditions, the Muun must celebrate at least one weeklong sacrificial ceremony during their lifetimes in order to appease the spirits and secure their place in the afterlife.

During that week, they will successively sacrifice a chicken, a goat, a pig, a buffalo and a buffalo captured from the wild. They will invite the shaman and fellow villagers to feast on the meat and will collect flat stones from the riverbed to build their own “House of Spirits” at the edge of the village. If this ritual is repeated in the course of any one villager’s lifetime, the observer gains the privilege of building his House of Spirits next to his home.

Though strongly committed to animism, most Muun are simultane-

ously Christian. One example of how this mixed religious tradition manifests itself is in the burial practices of the Muun. After the deceased is buried in accordance with Christian tradition, his body will the next day be dug up by friends and cremated, with the bones and ashes laid to rest under the stone stool of his or her House of Spirits. Chin State is perhaps the only place in the world where the cemeteries are empty. Makaan tribeswomen sport a spotted tattoo pattern forming lines on their forehead and chin, while Daai women

display a face covered with dots that are mixed with vertical and horizontal lines on the forehead and cheeks.

Ngagah, Daai, Muun, Yin Duu Daai and Uppriu tribes all live in the villages surrounding Kanpetlet.

Yin Duu Daai tattoos consist of vertical lines, including on their eyelids, while Uppriu women’s faces are completely covered with dark ink and Ngagah tattoos are a mix of vertical lines and dots.

Local lore has it that that these tribes first began to ink their faces as a way of disfiguring their beauty to avoid being kidnapped by the Myanmar king. A second legend states that they were tattooed distinctively to allow for identification with their tribe of origin in the event that they were kidnapped by another tribe. The latter seems more plausible, as this region has been visited by a Myanmar king only once, centuries ago. In any case, these women had to bravely withstand many hours of pain to have the ink embedded into their skin with citrus thorns.

While I was walking the threehour stroll from Mindat to the village of Kyar Do with Naing Htang, the son of a wealthy Mindat farmer, I noticed that huge chunks of the native forest had been cut down and sometimes replaced by bean or corn crops. Naing Htang explained that local farmers clear the forest to plant—and not long after exhaust—the newly made arable land. The fields’ soil stays fertile for just three years, after which the farmers are forced to move and plant their seeds on a new plot.

In this way, some 70 percent of the forest has been already cleared. After a cycle of nine years, farmers often return to the original block to re-plant, but the harvest’s yield is much lower. The monsoon season’s heavy rains wash the top soil down the land’s steep slopes, making that which is already unsuitable for farming even poorer. A high fertility rate of five children on average per couple adds demographic pressures on the land.

Naing Htang added that the area’s climate was becoming more arid as a direct result of the deforestation. He suggested that a solution would be to cultivate using terraced planting

techniques, which would help retain nutrients and top soil, and in turn eliminate the need for rotational farming. But for this they need better road access and machinery, and neither is so far forthcoming. In Naing Htang’s opinion, the farmers were aware that they were destroying their own environment but did it “for survival,” as he put it, rubbing his belly.

As we reached Kyar Do village, we heard hymns coming from a timber church up the slope. It was Sunday, and all the women of the village would be gathered there for the weekly service.

We joined the mass and witnessed the Christian fervor of the also-animist villagers. After the service I sat down with the priest, Law Aung, who had been preaching passionately a few minutes earlier. I asked him why the Chin people cling to livelihoods on these inhospitable slopes. He responded that it was to protect themselves from their enemies. When I asked him what could be done to improve the lives of his people, he went silent, and remained that way for so long that I repeated the question, thinking he hadn’t understood the query.

“If you could ask for one thing to improve the lives of the villagers, what would it be?”

“Too many things to ask,” he finally replied. “A road and flatter land.”

I asked what he envisioned for the future of the village.

“No future. The land will go down to the river one day and we will have to move elsewhere,” he gloomily predicted.

A community development team from Naypyitaw that I met in Kanpetlet was startled at the sight of my photos of the tattooed Chin women. They didn’t seem to know of these women’s existence. We told them about the situation in Kyar Do, preparing them for what they could expect to see in the surrounding villages.

Since last year, the villagers have been using a few 300,000-kyat (US$300) Chinese-built motorbikes to link the surrounding villages to Mindat. Small solar panels are providing some electricity to the largely off-grid people, and the villages have acquired a few mobile phones. But these changes, and the road the government is building a few hours’ walk away, may be too little, too late for the faces in this remote corner of Chin State.

In a country where talking about intimacy is taboo, efforts are under way to develop a better system for educating youths about safe sex

By SAMANTHA MICHAELS / YANGONAs a teenager, Ma Pan Ei Khaing never walked too close to boys, heeding a word of advice from her mother about unintended pregnancy.

Her friends in her native Bago Region were told by their parents not to have sex. “But my mother said that once I started menstruating, I couldn’t even touch a man, otherwise I would become pregnant,” she says. “I was afraid of that, so I stayed away.”

She busted that myth three years ago, when she turned 18 years old and decided to study health so she

could become a midwife. But today, despite her training, and although she believes communities would benefit from discussions about contraception, she is not widely sharing information about safe sex with patients.

In some parts of Myanmar, mainly urban centers, health-care workers discuss methods of preventing sexually transmitted diseases. But in the rural areas where Ma Pan Ei Khaing works, and where midwives are the sole providers of medical care, safe sex is not considered an acceptable subject for discussion.

U Sid Naing: ‘Schoolteachers are embarrassed.’

Below: Young people relax around Botataung port area in Yangon.

“The topic is a little strange,” she says. “And using condoms is seen as shameful. In this traditional culture, if you have sex before you marry, it’s like you did something wrong.”

In Yangon a young doctor has taken a different approach. To avoid the embarrassment of speaking face to face, he moderates a telephone advice hotline for young men who have questions about sexual health. The hotline is an initiative of the Myanmar Medical Association, an organization of physicians that has also created a separate line for women.

Some callers are shy at first, says 26-year-old Ko Zarni Win, who answers about five calls daily for the boys’ line. “They do not need to tell me their name so they can easily disclose their problems,” he says.

But the hotlines are not a cureall because a majority of people in Myanmar lack access to mobile phone networks, and other options for frank discussions are limited. Parents typically do not talk to their children about reproductive health, and although sex education is taught in schools, teachers worry their integrity could be questioned if they speak openly about the subject.

Myanmar is trying to answer a question that remains controversial in many countries: how to balance calls for comprehensive sex education as a tool to prevent teen pregnancies, sexually transmitted diseases and sexual violence, with concerns about protecting cultural values.

Myanmar women are traditionally expected to remain virgins until they marry, and while condoms are available in stores, young adults say they fear being labeled as promiscuous if they are caught with one in their bag.

Mi Phuu Pwint Aung, a 22-year-old from Mon State, has a boyfriend but says she is waiting to have sex and does not know how to use a condom. “If you are not a virgin when you get married, you have no dignity,” she says, adding that discussing reproductive health with her parents is not an option. “They would ask why I wanted to talk about something so disgusting.”

But Myanmar is not necessarily a place of innocence. Prostitution is illegal but easy to find in cities, while drugs to enhance libido are available cheaply on the black market and rooms

in guesthouses are rented by the hour near universities for couples looking for privacy.

Young people are commonly forced to marry against their will if caught having sex, while women with unwanted

“Knowing about your body is not against culture.”

–Ma Htar HtarMaha Bandoola Garden park is becoming a popular place for couples to meet. Ma Htar Htar: Women regularly report abuse.

pregnancies must have the baby or undergo an unsafe illegal abortion. Another concern is sexual assault, says Ma Htar Htar, a Yangon-based activist who says women regularly report sexual abuse at monthly sessions she leads to discuss gender roles, sexuality, reproductive health and other issues.

Ma Htar Htar formerly worked as a sexuality trainer for the Burnet Institute, an Australian organization seeking to prevent HIV, but says her understanding of sexuality at the time was limited. “For those who didn’t want to use a condom, what next? The conversation would always stop, because we didn’t know or want to talk about pleasure in sex,” she says. “We also were not trained to talk about sexual relationships, female sexuality. We focused on male sexuality, or more specifically on men who have sex with men.”

Today she is calling for more comprehensive sex education in schools.

“When people say sex education runs counter to Myanmar culture, it is because they do not understand what sex education is. They assume sex education is about intercourse, but no—it is about our organs, which we use in our bodies every second. Right now we are not meant to understand our organs, but we need to understand how they function, how to take care of them,” she says.

“Sex education is not just about sex, but about health, power, violence, law, sexual identities, how you see yourself, your image, your relationships, your communication and decision-making. Knowing about your body is not against culture.”

Sex education is promoted under the guise of HIV prevention in Myanmar, where about 200,000 people live with the virus and a large share of those requiring antiretroviral therapy are not receiving it.

“HIV allows us to talk about safe sex—that seems like the only venue,”

Students between the ages of 10 and 16 learn about safe sex as part of the “secondary life skills” (SLS) curriculum, which covers a range of topics from social skills and emotional intelligence to reproductive health and drug use. The curriculum is mandatory but co-curricular, meaning students do not have to take exams on the subject at the end of the year.

Lessons about puberty and HIV transmission begin in sixth grade, according to Unicef, which helped the Ministry of Education develop the curriculum. In 10th and 11th grades students learn that abstinence is the most effective way to prevent pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections, and that condoms are the only effective way for those who are already sexually active.

says U Sid Naing, the country director for Marie Stopes International, which offers reproductive health care services.

He says the government introduced sex education into schools about 10 years ago, but adds, “The majority of schoolteachers in Myanmar are women, and their capacity has not been built to confidently talk about safe sex and basic sex education. They are embarrassed, and their biggest fear is that if they talk about sex they will not be respected.”

Bertrand Bainvel, a Unicef representative in Yangon, says teachers in the past have used time allocated for sex education to teach other subjects that will be covered in exams. “Unicef is currently working with the Myanmar government to have SLS embedded in the national education law,” he adds.

Some young adults are in no rush to learn. “I don’t think I need to know more right now,” says Mi Phyu Phyu Win, a 22-year-old student in Yangon. “I might need to know one day, but I have never had a thought on it right now.”

Minutes later, she has a change of heart. “It is not something you can avoid,” she says. “It’s how you make babies, it’s how we are. We should know about it since we can’t avoid it.”

Maung Kauk Ya has to wake up at 4:30 every morning. While other children his age wait for school buses to arrive, this 13-year old boy starts working, taking orders from customers at a teashop in Yangon.

“I used to go to school, until I finished sixth grade,” he says.

Born the middle son of a toddy palm climber in Upper Myanmar, he left the classroom when he was 11 years old because his parents were too poor to support their six children. He found a job at the teashop, sending back every kyat he earned to his family. He also all but gave up on his dream to go to university—at least until recently, when a chance to learn came to him, on a bus.

“Our mission is simple: When children can’t go to schools, we bring schools to them,” says Daw Grace Swe Zin Htike, country director of the Myanmar Mobile Education Project (myME), a program that provides nonformal education via mobile classrooms to children who are forced to leave school to support their families.

The interiors of the buses are converted into mobile classrooms, where children have an opportunity

to learn basic literacy in Myanmar and English, as well as math, computer skills and critical thinking through innovative, interactive instruction.

Since last month one of the buses has been driving the streets of Yangon as part of a six-month pilot project, opening its doors to 120 teashop boys like Maung Kauk Ya who want to resume their studies. Classes meet six days weekly for two hours per session, in the evenings after the boys finish work.

“We started with teashops because you can mostly find primary and middle school dropouts working there,” says U Tim Aye Hardy, director of the project.

He says the mobile education project will be expanded later to include four levels of classes, from beginner to advanced, to prepare students for either formal education or vocational

training in the future.

“We are just shedding light on what needs to be done and filling in the gap: providing education to some working children who can’t go to school. But to address the entire problem, only the government can take care of it,” he says.

Myanmar culture traditionally places a high value on education, and net school enrollment rates are more than 80 percent for both boys and girls. But the drop-out rate is also high. According to Unicef, less than 55 percent of children who enroll actually complete the primary cycle.

Over five decades of dictatorship, Myanmar’s government invested very little in the education system. While tuition is free at government primary schools, parents have long been required to pay for books, school building repairs and even furniture

for classrooms—expenses that often present an insurmountable financial obstacle for impoverished households.

Facing tough economic conditions under the former regime, families around the country and especially in rural areas have frequently been forced to send their young boys to cities or towns for jobs in teashops or factories. Many girls also drop out but typically help with chores at home, rather than working at teashops.

This situation has not been greatly alleviated by education reforms initiated under President U Thein Sein since 2011; although his administration has called for free compulsory primary education, offering free textbooks and school supplies to students at the primary level, a lack of income for families means that many children are still required to work.

U Aung Myo Min, a human rights activist and director of Equality Myanmar, says the mobile education

project will not only promote children’s rights, but also hopefully help to identify some of the root causes of child labor in the country.

“The project is an oasis for working children who cannot go to school,” he says, adding, “They should consider a long-term strategy to eliminate child labor. Otherwise, the project will be caught up in an endless cycle.”

Just minutes after one of the buses arrived at a teashop in Yangon on a recent evening, 65 child employees hopped on board. Despite a long day of working as waiters, cooks and tea makers (known locally as a phyaw saya, or brew masters), they seemed enthusiastic about the opportunity to practice writing the English alphabet. Others sat around tables inside the teashop, paying attention to the lesson, and when their teacher pointed at a picture on a whiteboard, the students correctly identified it in unison as a “map.”

“I don’t feel tired. Instead, I am happy because I want to learn,” says Maung Kauk Ya, the 13-year-old son of the toddy palm climber, while completing an in-class exercise on building simple sentences in English. “I’m just grabbing my chance to learn now, because I want to be a university graduate to get a better job.”

Left: After a day of work, boys at a teashop in Yangon listen to an English lesson by the Myanmar Mobile Education Project.

Left: After a day of work, boys at a teashop in Yangon listen to an English lesson by the Myanmar Mobile Education Project.

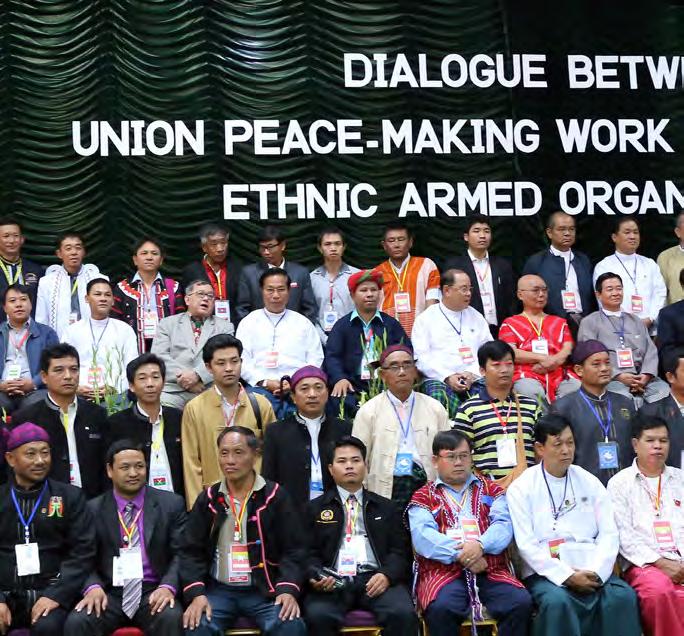

There is a reason why peace talks between the government and Myanmar’s ethnic resistance armies are not going anywhere: The two sides are fundamentally at odds over what they hope to achieve.

What the government wants is a “nationwide ceasefire” first, after which it will be up to the individual groups to convert their respective organizations into political parties, contest elections and then, if elected, discuss political issues in Parliament.

The non-Bamar ethnic groups, for their part, want a political dialogue to begin before they sign any nationwide ceasefire agreement. Even more importantly, they see the peace process as the first step towards re-establishing the federal structure Myanmar had before the military seized power in 1962 and abolished the 1947 Constitution.

However, the military—which stands behind the government— sees federalism as a first step toward disintegration of the country, and, therefore, unacceptable. Certain political issues can be discussed in Parliament, but “non-disintegration” of the country is one of six basic principles enshrined in the 2008 Constitution.

On the other hand, the ethnic resistance groups have not articulated their demand for federalism either. What kind of federal union would they want Myanmar to be? How should power be divided between the states and the central government? And what exactly is the “federal army” some of the groups have begun talking

about? Unless those issues have been made clear, there is little or no hope of the military changing its mind about federalism.

Many models have been mentioned: the United States, Canada, Germany, and even multi-ethnic Malaysia. The United States has a federal system, but it is not based on ethnicity, which is what Myanmar’s ethnic groups are demanding. There is no Anglo-Saxon,

Irish, Polish, Mexican, Chinese or Italian state in the US. The states there are purely geographical entities where a multitude of different peoples live.

Canada has a province with a French-speaking majority, Quebec, and the country has two official languages, English and French. In 1999, the predominantly Inuit-speaking parts of the Northwest Territories became a new territory, Nunavut, and there are other autonomous areas in Canada. But, by and large, Canada, like the US, is a country made up of various groups of immigrants and it is not a federal state based on ethnicity.

Malaysia is multi-ethnic, but there is no Malay, Chinese or Indian state in that federation. Malaysia’s federalism is based on the traditional Malay sultanates and some former British colonies and protectorates. But there are different ethnic groups living in all 13 Malaysian states. This is similar to the Federal Republic of Germany, which is made up of old kingdoms and principalities that were united in the late 19th century, except that the

resulting nation-state was, and still is, overwhelmingly German in its ethnic composition.

There are, in fact, very few federations that are—or rather were— based along ethnic or linguistic lines. One was the former Soviet Union, which was dissolved in 1991. Another was Yugoslavia, which fell apart in the 1990s following bitter wars between the country’s different ethnic groups. A third would be Belgium, which has only two major ethnic groups—the Dutch-speaking Flemish people and the French-speaking people of Wallonia— and a smaller German-speaking community in the east. But even with such few ethnic groups, Belgium has had immense problems maintaining its unity, let alone forming functioning central governments.

So are there any successful models Myanmar could follow? There seems to be only one: India. India has 28 states and seven union territories, and although the Indian constitution does not mention “federation” or “federalism,” the basic structure of the

country is federal. India’s constitution has three lists that empower the union and the states to legislate on various matters. For instance, each state has an elected legislative assembly, its own official language and its own police force. But defense is the responsibility of the central government. India has ethnic units in its armed forces, but it is not a “federal army”; it is all under central command. Any other model would be unworkable. The third list contains issues where both the union and the various states can legislate. It is a fine balance, but despite all India’s internal ethnic conflicts, it is working. Unlike the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, India has not fallen apart, nor is at as dysfunctional as Belgium.

But if Myanmar is going to follow the Indian model, be prepared for all the problems that would entail. There is not a single state or region in Myanmar that has only one ethnic group. There are frictions between Shans and Kachins in Kachin as well as Shan State; the Pa-O rebellion in Myanmar broke out in the 1950s, not against the central government but the dominance of the Shan sawbwas. The United Wa State Army, which is active in northeastern and eastern Shan State, wants a separate state for its people. And while there is a Mon State, the Mon people are perhaps the most assimilated of Myanmar’s many ethnic groups.

Myanmar’s 1947 Constitution, its first, could serve as a basis for discussion, but little more. Its most controversial clause is in Chapter X: The Right of Secession, which said that “every State shall have the right to secede from the Union” after 10 years of independence from British colonial rule. But other clauses stipulate that this right does not apply to Kayin or Kachin states, so it was only Shan State and Kayah State that could, at least in theory, secede from the Union. In any case, the clause was not meant to be exercised, but was put there to make the then proposed Union of Myanmar more palatable for the nonBamar peoples to join. The Mon, Chin and Rakhine states were not established until 1974, and therefore not covered by the 1947 Constitution.

Nor did the new constitution that was adopted in 1974 have any provisions

for federalism or regional autonomy— all that had disappeared after the 1962 military takeover. The 2008 Constitution is not federal in nature either. There is no difference between the states and the regions, and regional and state hluttaws do not have nearly as much power as, for instance, India’s state legislatures or those of non-ethnic federations such as the United States or Canada.

So what could a federal Myanmar look like? When the government embarked on its peace plan in 2009, the ethnic resistance armies were invited to become “border guard forces”—but that was a very ill-conceived idea. Border security in nearly all countries is the responsibility of the central government. In India’s northeastern states, adjacent to Myanmar, border security is in the hands of the paramilitary Assam Rifles, which is under the control of the Ministry of Home Affairs in New Delhi. There are also other centrally controlled border guard forces, and sometimes local police may assist but not be responsible for border security.

On the other hand, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram and other Indian states have their own armed police forces that are under the command of their respective state governments. If that system was adopted, the Kachin Independence Army or the Shan State Army could be absorbed into a Kachin State or Shan State Armed Police Force, but not into locally commanded “border guard forces,” which could easily degenerate into bands of border bandits and smugglers.

The Myanmar government and the country’s armed resistance groups need to find a model that works, and the most viable solution would be to study the Indian model. It is also important to remember that when the Shans, the Kachins and the Chins signed the Panglong Agreement with U Aung San on Feb. 12, 1947, it was clearly stated that “full autonomy in internal administration is accepted in principle.” That was the principle upon which an independent Myanmar was founded, and it is still the only solution that would satisfy the aspirations of the country’s non-Bamar ethnic groups.

Myitkyina, Kachin State, in November 2013.

Myitkyina, Kachin State, in November 2013.

By KYAW PHYO THA / NYAUNG SHWE TOWNSHIP, Shan State

By KYAW PHYO THA / NYAUNG SHWE TOWNSHIP, Shan State

Gazing out over the vast expanse of Inle Lake, Daw Yin Myo Su remembers the good old days for Myanmar’s second-largest body of fresh water, which is surrounded by misty mountaintops in her native southern Shan State.

As a child she paddled across the lake to visit relatives who, like the other ethnic Intha families that populate the area, lived in wooden houses perched on stilts over the water. During those trips across what is now one of Myanmar’s most famous tourist destinations, she witnessed scenes that no longer exist today.

“Believe it or not, at that time you could drink the water in the middle of the lake when you got thirsty. You could swim. Fish were abundant, and drought in the summer was unheard of,” the 42-year old says. “The situation now is as different as water to oil.”

Speaking from the veranda of the Inthar Heritage House, a center she founded on the lakeshore to preserve Intha cultural traditions, she says the situation on Inle has visibly worsened but is not yet hopeless. “We can still fix up our lake,” she says.

Situated 900 meters above sea level and nestled at the foot of the Shan Hills in Taunggyi District, Inle has long been a popular stop for international tourists, thanks to its iconic leg-rowing fishermen,

floating gardens, stilt houses and biodiversity.

But activists and policymakers say the lake is on the verge of environmental disaster. Sewage and agricultural chemicals have polluted the water and poisoned the fish, while sedimentation has made the 100-square-meter lake shallower. Local population growth and tourism have added to the strain.

The most evident deterioration came in the summer of 2010, when an unprecedented drought in the region dried up much of the lake. The drought resulted from deforestation around the lake and several years of poor rainfall, and it led to severe sedimentation. By April, the vast area of water had shrunk by one-third, turning the vicinity of Phaung Daw Oo Pagoda, a sacred Buddhist pilgrimage site usually accessible by boat, into a virtual wasteland. Villages on the lake were also affected.

“I had to take a motorbike to go to my house because there was no water,” said Buddhist monk U Vijja Nanda of his attempt that year to visit family in Hpa Kone village, where houses had previously been propped up by stilts over the water.

After the drought, the government hastily drafted a five-year conservation plan to reverse environmental degradation and assist local residents. Nearly five years later, UN agencies are offering assistance to develop a new conservation plan, with technical support from Norway.

But today the problem may be more complex.

“A drop in water quality is also a serious issue,” says environmentalist U Aung Kyaw Swar, who is also the principal of a hospitality vocational training center linked with Inthar Heritage House. For two years, the heritage house has collected water samples at five locations around the lake, sending them to laboratories for testing.

“Most of the results show the water is contaminated with a heavy metal like lead that could be cancerous if consumed,” he says, adding that farmers who grow tomatoes and other vegetables on floating gardens use excessive quantities of chemical fertilizers and pesticides to boost yields.

The agricultural practice could devastate the ecosystem of the lake, which boasts 59 species of fish, including 16 that are endemic, according to the Inle Wetland Wildlife Sanctuary.

“They spray it directly on the plants in unregulated amounts,” the environmentalist says. “The agricultural runoff contains chemical pesticides and pollutes the water.”

Population growth has also had ill effects. Most of the more than 100,000 people currently living in homes over the lake and on its edges regularly dump sewage into the water, while small family-run weaving and silversmith businesses allow untreated wastewater to flow.

The lake’s natural filtration system may have managed this issue in the past, but the pollution is now too severe. The Department of Fisheries last year reported that pH levels, a measure of acidity, had risen to between 8.4 and 9.6 at points on the lake, endangering once-abundant native fish species such as the Inle carp (Cyprinus carpiointha, known locally as Nga-phane).

As a result, fisherman U Myo Aung takes home a smaller load these days.

“I only catch about 3 viss [4.8 kg] after spending the entire day on the lake,” the 36-year-old says, compared with bringing in at least 4 or 5 viss on a single morning before the fish began dying out.

On the keel of his wooden boat sits his catch of the day: tilapia, a hardier species that was introduced to the lake because it can withstand the chemicals, but which is reportedly less tasty than the

native Nga-phane.

“I earn just 1,000 kyat [US$1] for one viss of tilapia. They are the only fish I catch, but not in a very large amount,” says the father of four.

Another reason for fish scarcity is the popularity of electric shockers among fishermen. The technique is an effective method for stunning the fish before they are caught, but it also devastates microorganisms in the lake that can improve water quality.

“They use it because they lack other economically viable alternatives,” says U Sein Tun, the park warden of Inle Lake

Daw Yin Myo Su is no Johnny-come-lately to the hospitality industry. As a young girl she performed traditional dances to entertain guests at an inn run by her family in Nyaung Shwe, a town near Inle Lake, and today she is managing director of two resorts: Inle Princess Resort, also near the Shan State lake, as well as Mrauk Oo Princess Resort in Rakhine State.

But Daw Yin Myo Su, also known as Misuu, is a woman of many interests, with a reputation near the lake for founding the Inthar Heritage House, a center dedicated to preserving the ethnic Intha traditions of her ancestors. She is also the winner of the 2013 Goldman Sachs & Fortune Global Women Leaders Award. In a conversation with Irrawaddy senior reporter Kyaw Phyo Tha, she discussed environmental conservation and women’s empowerment, and explained why she believes development should not come at the cost of local culture.

What’s your vision for Inle Lake?

I belong to the Intha tribe and had many sweet childhood memories at Inle Lake, so I’m very proud to come from this simple and warm Inle community. My vision is not that complicated. I believe I inherited the lake from my ancestors, so it’s my responsibility to hand it over to the next generation just as I received it, but with some improvements, like in health and education. I understand nothing lasts forever but I don’t want to give it up without a try.

Now tourists are rushing in. Will this help improve the lake and the lives of local people?

So far it has generally had a positive

impact on Inle people indirectly, by creating jobs as local guides, boat drivers and souvenir sellers. But there are no more than a dozen locally owned hotels and very few successful local entrepreneurs. With tourism booming, I think locals should see a good share of the benefit. If not, in the long term they will feel alienated.

Do you mean you oppose foreign investment or foreign-run hotels?

No, I don’t. You can even learn from them. Instead of seeing them as rivals, we have to compete with them by offering quality services to guests. At the same time, if they want to sustain their businesses, outside investors should take care of the local community. If Inle is no longer attractive to tourists, no one will come—no matter how much you invested. Of course we all need to make money, but you have to contribute to the community. Foreign investors are welcome. Show us a smart way to invest, teach us a smart way to work, be our model. Inspire us. Help us this way, and we will help you. It’s a winwin situation.

How can local businesses stay competitive?

Being a local is part of the brand—it’s valuable. Being a local is attractive for tourists who want to visit our country because they really want to understand who we are or how we live. They don’t come here to see something they can see in other countries. For them, something local is authentic. You have to be creative with your current assets to ensure the comfort of your clients. Plus you need to work as hard as foreigners. Don’t be lazy, especially at this moment when everyone is interested in Myanmar.

What are you doing now?

I’m working on the Inle Heritage Foundation to preserve the tangible and intangible heritage of Inle and its surroundings. I started with breeding Burmese cats at the Inthar Heritage House, and I also have an aquarium that conserves the endemic fish species of Inle Lake. Since last year we have run a hospitality vocational training center at the Inthar Heritage House for local young people, to help the community diversify their livelihoods and get a bigger share in the development of this industry. We are also running pilot projects on good agricultural practices and waste management for the lake.

Why did you go into the hospitality industry?

Hospitality is in every Myanmar person’s DNA. It is taken for granted in Shan State that even a stranger will have a cup of green tea when he drops by at a farmer’s home. I feel great when I make someone happy. I want to help people. If guests tell me during checkout that they were satisfied with our service, I’m on cloud nine! That kind of happiness is beyond expression. Plus I get money from them. Don’t you think it’s good?

Wildlife Sanctuary, who has helped spearhead an education campaign to deter the practice. Last year 40 fishermen were arrested for using the electric shockers.

Whether or not his campaign is successful, other environmentally harmful practices have persisted.

“Activities that negatively impact the health of the lake have not changed,” says Joern Kristensen, director of the Institute for International Development (IID), an Australia-based organization which in 2012 sent a report with recommendations for conservation and sustainable management to the Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry.

“There is still considerable overuse of chemical fertilizer and pesticides negatively impacting the water quality. There is still untreated wastewater being let out into the lake from households and cottage industries, there are still trees being cut down around the lake to provide firewood for cooking, leading to soil erosion, and there is more noise from the growing number of boats on the lake.”

In the 2012 report, the IID called for the formation of a single body to oversee conservation efforts at the lake. In January this year, President U Thein Sein gave his backing to the new Inle Lake Conservation Authority, which will coordinate and monitor all conservation activities, prioritize investments and project funding, and store data about the lake into a shared database.

“Everything is connected and needs to be managed in an integrated, holistic manner,” says Mr. Kristensen.

In particular, he says it will be crucial to manage new income–generated in part by increasing tourism–toward projects that help maintain the health of the lake.

“This requires involvement and support by all interested parties, in particular the private sector, which benefits from the opening of Myanmar and has a strong interest in maintaining the lake region as an attractive destination for foreign and international visitors,” he says.

Tourism has boomed over the past three years, with nearly 100,000 visitors heading to Inle Lake in 2013.

“We expect to have more than 150,000 visitors this year,” says U Win Myint, the Intha affairs minister for the Shan State government.

Foreigners must pay a US$10 admission fee to see the lake, and half that money goes toward infrastructure development, while the rest goes to the state government. But the minister says little has been done to invest in the livelihoods of local people, who continue to use chemicals and electric shockers, while also throwing sewage into the water.

“They know what they are doing is bad, but they don’t have economically viable alternatives. This is a problem that still lacks a solution,” he says.

Construction of hotels and an

increase in foreign investment could create jobs, he says, after the government approved a new hotel zone that will cover 662 acres on the lake’s eastern shore.

And if residents living at the lake can take up hospitality jobs, they may find the means to support their families, adds Mr. Kristensen of IID.

“If young people who belong to the region are trained and find employment in the tourism industry, they will be good ambassadors for the lake,” he says, while also laying out a less optimistic alternative: that new jobs go to people from Lower Myanmar who can speak English but do not understand the lake’s cultural and environmental heritage. In that case, he says, “The next generation of farmers will continue unsustainable agriculture.”

In the meantime, the hospitality training center at the Inthar Heritage House is staying busy. All 39 students at the center grew up on the lake and its surroundings. Most received scholarships to the center because they could not afford the tuition fees.

“As tourism booms and job opportunities open up, we are simply meeting the demand for qualified employees who are not only skillful, responsible and caring to guests, but also mindful about improving conditions of their family, Inle Lake and the country,” says U Aung Kyaw Swar, the principal.

Daw Yin Myo Su, founder of the Inthar Heritage House, also chairs the training center and is now working on pilot projects to promote better agriculture practices and wastewater management systems on the lake.

“I believe if everyone contributes what they can, it’s possible to make a change, no matter how bad the situation is. I just do what I can because I want to hand over the lake to the next generation in the same condition that I received it from my ancestors.”

As Myanmar’s economic opening continues apace, hopes are high for plans to launch the country’s first full-fledged stock exchange in more than 50 years. But while the new bourse looks set to meet a late 2015 deadline, observers say a number of key issues could still present major obstacles.

Last September, the government and Parliament approved the Securities Exchange Law, clearing the way for the creation of the new Yangon Stock Exchange (YSE) in October 2015. Earlier, in May, the Central Bank of Myanmar and Japan’s Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) and Daiwa Securities Group had reached an agreement to establish the YSE as the first market of its kind since the economy was nationalized after a military coup in 1962.