www.irrawaddy.org TheIrrawaddy Movie Month in Yangon Mattress Pioneer Makes his Mark Women’s Input Vital for the Country Democracy: It’s Not Just for Some September 2014

ECONOMY: TIME FOR

TRAVEL TO THE DEEP SOUTH

TAY ZA’S TRAVAILS

THE

A DEBATE? ROAD

U

No.86/A, Shin Saw Pu Road, Sanchaung Township, Yangon. Tel. 09 450013761 E-mail : info@lanacha.com www.lenacha.com Nacha Restaurant Nacha Spa beauty and wellness Authentic Thai foods by a Thai chef Relax your mind, your spirit, and your body and embark on a journey of well being. ......... .........

www.gmairlines.com HOT LINE: +95 1 860 4036 www.facebook.com/GMAirlines

Irrawaddy September 2014

• Restaurant since 2002

• Tavern with 24 Twin Rooms

• Restaurant capacity 180 Pax

• Myanmar and Chinese Cuisines

• Home-cooked curries & more

• Packed Lunch Boxes available for Cruises & late flights.

No. 1-A / 3, 28th Street,

(One block away from Rupar

Resort) Tel: 09-910 48506, 09-500 2151 www.littlemandalay.com E-mail: littlemandalay@gmail.com ...truly Mandalay ...simply quaint...

Between 52nd x 53rd Streets, Mandalay.

Mandalar

5

TheIrrawaddy

TheIrrawaddy

The Irrawaddy magazine has covered Myanmar, its neighbors and Southeast Asia since 1993.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Aung Zaw

EDITOR (English Edition): Kyaw Zwa Moe

ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Sandy Barron

COPY DESK: Neil Lawrence, Paul Vrieze, Samantha Michaels, Andrew D. Kaspar, Simon Lewis

CONTRIBUTORS to this issue: Aung Zaw, Kyaw Hsu Mon, Bertil Lintner, Emma Larkin, Patrick Brown, Simon Lewis, Mark Inkey, William Boot, Khine Thant Su, Jessica Mudditt.

PHOTOGRAPHERS : JPaing; Sai Zaw, Hein Htet.

LAYOUT DESIGNER: Banjong Banriankit

SENIOR MANAGER : Win Thu (Regional Office)

MANAGER: Phyo Thu Htet (Yangon Bureau)

REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS MAILING ADDRESS: The Irrawaddy, P.O. Box 242, CMU Post Office, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand.

YANGON BUREAU : No. 197, 2nd Floor, 32nd Street (Upper Block), Pabedan Township, Yangon, Myanmar. TEL: 01 388521, 01 389762

EMAIL: editors@irrawaddy.org

SALES&ADVERTISING: advertising@irrawaddy.org

SUBSCRIPTIONS: subscriptions@irrawaddy.org

PRINTER: Chotana Printing (Chiang Mai, Thailand)

PUBLISHER LICENSE : 13215047701213

6 TheIrrawaddy September 2014 Contents 8 | In Person Why Women Are Needed 10 | Quotes and Cartoon 12 | News Highlights 14 | In Focus 16 | Viewpoint On Obama’s Foreign Policy Report Card, Myanmar Gets a Pass LIFESTYLE 51 | COVER Young, Gifted and Searching Style pioneers seek the light 56 | Travel: In Search of the Deep South Traveling overland to Myanmar’s southernmost point takes stamina and determination 62 | Restaurant: Northern Thai Style Fresh and full of flavor, the cuisine has ancient links with Myanmar 64 | Backpage: Movie Month The Wathann Film Festival is coming up and will include a special screening of “The Monk”

Vol.21 No.8

COVER PHOTOS : Diana Markosian

www.irrawaddy.org TheIrrawaddy Movie Month in Yangon Mattress Pioneer Makes his Mark Women’s Input Vital for the Country Democracy: It’s Not Just for Some September 2014 THE ECONOMY: TIME FOR A DEBATE? ROAD TRAVEL TO THE DEEP SOUTH U TAY ZA’S TRAVAILS

18 | Photo Essay: Prison Fight

Prisoners in Thailand can win respect, better conditions and time off their sentences if they defeat foreign opponents in jail-yard boxing matches

24 | Feature: The Ties That Bind

An army past has long been the best asset a businessman can have - but that may be shifting

28 |

Politics: Making a Mockery of Democracy

The nations of Asia deserve real democracy, not a watered-down version

32 | Feature: Finding George Orwell in Bangkok

The dystopian masterpiece “Nineteen Eighty-Four” makes a surprise appearance amid the plush shopping malls of the Thai capital

35 | Policy: Debating the Economy

Economic liberalization can strengthen the resourse curse and enrich elites. One researcher proposes some perhaps controversial remedies.

40 | Interview: Business with Bounce

46 | Signposts: Local Companies Invest

US$45 Million in Napyitaw Hotel

48 | China: TV Series on Deng Raises Questions

A drama series on state television on late leader Deng Xiaoping is a rare portrayal of a top politician

7 September 2014 TheIrrawaddy

FEATURES

BUSINESS

REGIONAL

P-62

P-16 P-18 P-35

Why Women Are Needed

What has been the status of Myanmar women over the course of history?

If you look at the present situation, the status of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi as a leader makes people think there is no gender inequality here. If you ask the ministers, they’d add that their wife has a say in their family.

Judging from this, people are often misled that gender equality exists in Myanmar. But women have to struggle to support their families. It is also not easy for women to ride a bus without having to worry about their safety. There are now more cases of young girls being raped. There were many female tycoons in various industries before, but nowadays almost all the tycoons in Myanmar are male.

During colonial times, Myanmar was admired for its society, which respected women and granted them a lot of rights. But now, even on a regional scale, Myanmar is the country with the smallest proportion of women participating in parliamentary affairs. Only 5.4 percent of all parliamentarians are women.

If people in Myanmar understand gender as you have explained it, what improvements do you think we will see in the future?

Dr. Khin Mar Mar Kyi is an award-winning social anthropologist and documentary filmmaker specializing in Myanmar, Southeast Asia and gender issues. She has served as a senior advisor to the Australian government and a lecturer at Australian National University, but now works at Oxford University in the United Kingdom.

During a recent visit to Yangon as part of an Oxford University delegation, she sat down with The Irrawaddy’s Khine Thant Su to talk about the place of women in Myanmar society, politics and the nation’s peace process.

If they understand gender as not just women’s rights but as their responsibilities, values and beliefs derived from the Myanmar tradition, men will see gender issues as not just concerned with women but concerned with men, too. So men will participate in addressing gender issues in Myanmar. That would be an improvement. If a man saw a woman being treated without

IN PERSON

PHOTO: SAI ZAW / THE IRRAWADDY

Dr. Khin Mar Mar Kyi says women must be allowed to participate more fully in Myanmar's ongoing peace process.

8 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

respect, fairness or with violence—even if only verbally—he would stand up for her if he feels it is a cultural insult for all Myanmar men.

What improvements and regressions have you noticed in addressing gender issues since the U Thein Sein government came to power?

Women’s forums can now be held freely. More women are involved in peace talks, but they are only decorative. In reality, women have no say in decision-making. The Parliament is also male-dominated.

Obtaining peace is crucial in transforming the country. And peace is impossible without addressing gender issues. Currently, if we look at the global level, many countries, including East Timor, Rwanda and Northern Ireland, all included women in their peace talks. We need to include women in peace talks because women are not only half of the population but also half of the resources of our country. You cannot afford to waste half the population and resources in these peace talks. No women, no peace.

Moreover, in traditional Myanmar culture, women are the ones who harmonize the household. In conflictridden ethnic regions of Myanmar, women are the ones who have to handle such difficulties as wartime survival.

What are some of the differences between an ordinary maledominated country and one that has been under military rule?

The military is an extreme form of male dominance, an extreme form of patriarchy. In places of military dominance, women can never be valued, women can never be equal, their rights are not protected and their needs are not considered. In places where the military dominates, women face extreme discrimination. The extremely

male-dominated military subculture, within the bigger cultural context of Myanmar, especially deprecates women.

How much do history and culture play a role in creating this kind of mentality?

Different circumstances and times can change a culture. During colonial times, every book about Myanmar women written by Western authors couldn’t help but reflect in wonder on Myanmar women’s high social status. Myanmar women dominated the economy. They had rights in marriage and divorce, property rights and the right to freely travel. These were rights that women in the West couldn’t dream of [at the time].

Eventually, those rights came to be called “feminism” by Westerners. Westerners thought Myanmar men had become useless because they were living in a female-dominated society. The colonizers saw traditional Myanmar culture as an uncivilized culture that they therefore had to change. They started to teach girls in missionary schools how to be feminine. During the nationalist movement, this perception of a feminine woman continued.

How long do you think it will take to change the mentality of the former military leaders in government?

One problem is that it will take time to change. So instead of trying to change their perception on the spot, we just have to ask upfront for women’s rights. That’s why we need quotas. On one

hand, we can give them reasons as to why addressing gender issues is important, but at the same time, we need to ask for women’s rights directly.

What do you think of the proposed interfaith marriage law restricting Myanmar Buddhist women from marrying a person of a different religion?

Today we should stop this “discipline and punishment” approach; we all need to develop critical thinking. If they reason that they need this law because financial difficulty and lack of knowledge are causing women to be lured [into marriage], then we need to support women to have financial security, knowledge and autonomy. We need to empower them to make the right decisions to protect themselves not just from men of other religions but also their own. We cannot just target other religions but also [need to look at] our own. How many women are facing domestic violence and sexual abuse at the hands of men from their own religion? Without empowerment of women, women will always be vulnerable, regardless of religion.

This law creates a loss of her traditional and legal position as wife, or even more importantly, [may lead to] genderbased violence and discrimination.

According to this law, a woman needs written permission from her parents and the local authorities, as well as [her prospective husband’s] conversion, in order to marry him legally or she will face 10 years’ imprisonment. It underestimates our traditional customary values. And the choice should be hers.

“In places where the military dominates, women face extreme discrimination.”

9 September 2014 TheIrrawaddy

QUOTES

CARTOON

10 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

“Next year’s election will absolutely be a benchmark moment for the whole world to be able to assess the direction that Burma is moving in.”

—US Secretary of State John Kerry, quoted in the New York Times during a visit to Myanmar in August

ILLUSTRATION: ATH All Afloat

‘‘The government agreed to have a federal system… this is the really important point.’’

—Nai Hong Sar, head of the Nationwide Ceasefire Coordination Team, after the conclusion of peace talks between government negotiators and the leaders of ethnic armed groups in August. Talks resume this month.

“Myanmar’s political system is not an obstacle for SinoMyanmar relations. Myanmar is only trying to normalize relations with the US and other Western countries, yet our relationship with China has reached the level of strategic partnership.”

—Minister of Information and president’s spokesman U Ye Htut, speaking to Hong Kongbased Phoenix TV in August

Myanmar Abuzz over Phones

world’s most poorly connected nations.

Consumers descended in droves on mobile shops carrying the Ooredoo advertisements that had plastered the commercial capital for months.

Charges Reduced for Journalists Accused of Sedition

The streets of downtown Yangon and other centers were abuzz in early August as consumers, who were for years deprived of affordable mobile telecommunications, raced to handset shops offering longawaited SIM cards from the Qatari telecoms firm Ooredoo. August may well mark the beginning of a telecommunications revolution in Myanmar, as Ooredoo became the first foreign firm to see its SIM cards on the streets of one of the

Ooredoo, along with Norwegian firm Telenor, won a license to operate a mobile network in Myanmar in June 2013, and has since been erecting mobile towers and marketing its brand.

Ooredoo Myanmar said the network will reach 25 million people in 450 cities by the end of the year. Farther flung places, including Sagaing Region, Ayeyarwady Region, parts of Bago Region, and Kayin and Mon states, should get coverage before next year, according to the company.

Rival firm Telenor has said it hopes to put SIM cards into the market later this year.

The Woodside Myanmar Postgraduate Scholarship at UWA

Five members of a local journal accused of inciting unrest will face less severe charges than expected after a court in Yangon’s Pabedan Township decided on Aug. 4 that they should be tried for violating Article 505(b) of the Penal Code.

According to a lawyer for the five journalists, editors and publishers of the Bi Mon Te Nay journal, they were originally charged under Articles 5(d) and 5(j) of the 1950 Emergency Provisions Act, which set out lengthy prison sentences for affecting the conduct of the public or undermining law and order.

“Under the previous charges they could receive seven years’ imprisonment for each charge, but the new charge carries a maximum punishment of two years’ imprisonment,” said defense lawyer U Robert San Aung.

The charges stem from a front page story carried by the now-defunct weekly based on a statement by an activist group that mistakenly claimed opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi had formed an interim government. —Htet Naing Zaw, Nyein Nyein and Yen Snaing

Woodside Energy Ltd has partnered with The University of Western Australia (UWA) to offer a high-achieving Myanmar national the opportunity to complete a Master of Public Health.

With an outstanding international reputation in health and medicine, UWA offers the successful candidate a transformative learning experience led by award-winning educators.

UWA and Woodside aim to create sustainable health benefits for the Myanmar community.

The Woodside Myanmar Postgraduate Scholarship provides one eligible Myanmar student with A$125,000 to undertake the Master of Public Health (Coursework) at UWA.

For more information and how to apply visit scholarships.uwa.edu.au/Myanmar

Closing date: 30 October 2014

NEWS HIGHLIGHTS ADVERTISEMENT

UWADAR002 CRICOS Provider Code 00126G 12 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

A mobile phone user in Mandalay holds up a newly bought Ooredoo SIM card.

/

PHOTO: TEZA HLAING

THE IRRAWADDY

Chinese Jade Scam Hits Myanmar Dealers

Hundreds of people, including jade dealers from Myanmar, saw their fortunes vanish overnight in a scam involving up to 1 billion yuan (US$160 million) worth of jade treasures taken by a Chinese conman, according to police in the country’s Yunnan Province.

According to a preliminary police investigation, 33-year-old Zhong Xiong approached dealers with offers to help them find wealthy clients in Shanghai and Beijing.

“He presented himself as a rich man to approach potential dealers who were desperate to sell their products,” according to one jade dealer surnamed Xie, who said he was approached by Zhong.

Every year, a large number of raw jade stones are shipped to Yunnan from neighboring Myanmar, which produces the world’s highestquality jade. The jade trade between the two countries— much of it illicit— was estimated at $8 billion in 2011 by the Harvard Ash Center.

Revelations of the scam come amid a sharp downturn in China’s jade market, which police believe may have prompted jewelry traders and individual lenders to be duped by Zhong’s promises that he could help them sell off their surplus stock.

Xie said jade dealers would most certainly be more cautious in the future, but the trader remained optimistic about the jade market’s future prospects.

“Twenty years ago, only people who lived in affluent areas like Hong Kong, Taiwan or Guangdong bought jade, but now there are buyers from every part of China,” he said.

—Echo Hui

Police under Siege after Clash with Villagers

Dozens of police officers were forced to barricade themselves inside a village school in Mandalay Region on Aug. 14 after firing shots at protesters attempting to reclaim land seized by Myanmar’s armed forces.

Three protesters were injured, one of them seriously, when about 50 police officers confronted the protesters in the village of Nyaung Wun, Sint Gu Township. Witnesses said the police opened fire when the villagers, who had begun plowing land that had been confiscated by the military, demanded to know why they were there.

The police then fled to a local schoolhouse, which the angry villagers surrounded to demand the release of a villager who had been arrested and an explanation for the use of force by the authorities.

The incident ended peacefully after the police were allowed to leave the school unharmed following negotiations at the local monastery.

The villagers later said they would press charges against the police officers responsible for the shooting.

“We want justice for what happened here. We believe there will be rule of law and the police who opened fire will be punished for what they have done,” said U Tin Naing, one of the villagers who submitted the case to the Sint Gu Township court. —Zarni

Mann

Five Million Sign Petition Calling for Constitutional Reform

Myanmar’s main opposition party and a leading activist group submitted a petition to Union Parliament Speaker U Shwe Mann on Aug. 13 with the signatures of five million people supporting calls for constitutional reform.

The petition, organized by the National League for Democracy and the 88 Generation Peace and Open Society, calls for a review of provisions in the country’s 2008 Constitution that guarantee a leading role for the military in Myanmar’s political affairs.

“We want the public’s demands to be heard,” said 88 Generation

leader U Ko Ko Gyi, calling on Parliament to seriously consider the political implications of the call of millions of citizens for reforms to the undemocratic 2008 charter.

However, a senior ruling party member was dismissive about the petition.

“There are few people who actually read the Constitution and are aware of the benefits and disadvantages of it,” said lawmaker U Tin Maung Oo of the militarybacked Union Solidarity and Development Party. —Nyein Nyein

13 September 2014 TheIrrawaddy

Potential buyers examine a piece of raw jade at the 2014 Gems Emporium in Naypyitaw.

/

PHOTO: SAI ZAW

THE IRRAWADDY

PHOTO: SAI ZAW / THE IRRAWADDY

Artists and performers in Yangon sign a petition to show their support for the campaign to amend Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution.

14 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

IN FOCUS

Connected!

A youth takes a “selfie” as she takes part in a cosplay competition at Saya San Plaza in Yangon on Aug. 3. Yangon was abuzz during August with the arrival of new SIM cards from telecoms firm Ooredoo, hailed as the start of a communications “revolution” in the country. Youth in particular are excited, as many look to international trends as the country opens up.

Hugely popular in Japan for decades, cosplay is increasingly taking off among Myanmar’s youth who are entranced by the colorful costumes of Japanese anime and manga. Hundreds of fans came out at the competition dressed as their favorite characters.

15 September 2014 TheIrrawaddy

PHOTO: REUTERS

On Obama’s Foreign Policy Report Card, Myanmar Gets a Pass

lakeside residence in Yangon, the same venue where she received Mr. Obama in 2012—when the country’s reforms were subject to much less skepticism than today.

Indeed, many in Myanmar were counting on the United States to inject some life into a reform program increasingly viewed as stalled. Mr. Kerry would not leave the country empty-handed, the thinking went, without a concrete expression of the government’s commitment to further reform.

Details of Mr. Kerry’s talks with both U Thein Sein and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, however, were not made public, with Mr. Kerry revealing little other than to say that he had a “frank” discussion with the president.

Promises

By AUNG ZAW

He offered a slightly more critical assessment in remarks at the East-West Center in Honolulu following his trip to Myanmar.

Next year’s elections in Myanmar will be a key indicator of how leaders in the country want to move forward, with many an assessment of the reform process hinging on the outcome. Among those who will be watching the election returns will be US President Barack Obama, for whom the stakes may be a bit higher than most: Having failed elsewhere in the world, Mr. Obama in 2014 finds his foreign policy assailed by critics, and his legacy on the global stage in doubt. In Myanmar, the US president has taken credit for reforms enacted since 2011, but has he gone “all in” on a questionable hand?

Many in dissident circles have warned that there should be a Plan B. What if, as in 2010, the election is rigged and conducted without transparency? What if it lacks

inclusivity? Will the United States stand by such a government as a partner in reform, as it has since Myanmar’s nominally civilian leadership took power in 2011?

John Kerry, the US secretary of state, visited Myanmar in August and said the United States would do everything it can to encourage reform in the country, especially by supporting nationwide elections in 2015.

“Next year’s election will absolutely be a benchmark moment for the whole world to be able to assess the direction that [Myanmar] is moving in,” he said in Naypyitaw.

Mr. Kerry met Myanmar’s President U Thein Sein and opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the latter of whom remains constitutionally barred from running for president as the country heads into next year’s pivotal elections. She met Mr. Kerry at her

“Defining a new role for the military; reforming the Constitution and supporting free and fair elections; ending a decades-long civil war; and guaranteeing in law the human rights that [Myanmar’s] people have been promised in name,” he said, referring to some of the challenges still facing the Southeast Asian nation.

“All of this while trying to attract more investment, combating corruption, protecting the country’s forests and other resources. These are the great tests of [Myanmar’s] transition. And we intend to try to help, but in the end the leadership will have to make the critical choices.”

Underneath all the rhetoric on democracy, human rights, and free and fair elections, there is major US commercial interest in resource-rich Myanmar, a country strategically located between China and India.

Before Mr. Kerry’s visit, US Secretary of Commerce Penny Pritzker in June made her first visit to Myanmar, a strong indication of Washington’s high-level commercial push. The United States opened the way for economic engagement with an easing of sanctions on Myanmar in

VIEWPOINT

The US president had better hope that his one foreign-policy success story doesn’t fall flat in the end

16 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

2012. Last week the United States went further, waiving remaining sanctions on Myanmar’s timber sector for one year. The decision was not without controversy, prompting an outcry from some civil society groups.

Economic Ties

During a visit in which she opened a new Commercial Service Office at the US Embassy in Yangon, Ms. Pritzker stressed the United States’ commitment to closer economic ties. As of April 30, 2014, American companies had plans to invest US$244 million in Myanmar’s economy, and US exports had increased from $9.8 million in 2010 to $145.7 million in 2013.

“Our Commercial Service officers help to increase opportunities globally, for our businesses and for yours,” she said, adding that US companies would bring technical know-how and a commitment to corporate social responsibility.

US businesses are coming to Myanmar in what looks like an increasingly unstoppable tide, and to facilitate investment, some blacklisted cronies may benefit. One already has, with Mr. Kerry staying at a blacklisted tycoon’s hotel in Naypyitaw during his visit. Forced to respond to questions

about the sleeping arrangement, the State Department insisted America’s chief diplomat was not in violation of the blacklist sanctions, but not before controversy had been stirred.

Those currently on the Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) list are prevented from doing business with US firms, but in June senior State Department officials met privately with some of these tycoons, telling them to put forward a request to have their names cleared. They would be expected to show their commitment to transition, sever ties with the military, avoid involvement in land seizures and respect civilian rule. It is only a matter of time, it seems, before some cronies are removed from the blacklist, having been sufficiently rehabilitated in the eyes of US officials at the Treasury Department.

It is difficult to know whether the United States’ fast-moving policy on Myanmar might have been different, more critical perhaps, had the international landscape been more kind to the US president.

Once a pariah and still frequently taken to task by the international human rights community, Myanmar is Mr. Obama’s sole foreign policy success story over the course of a presidency of global chaos that some critics have

chalked up to a failure of White House leadership.

In an address at West Point in May, he claimed, “We’re now supporting reform and badly needed national reconciliation through assistance and investment, through coaxing and, at times, public criticism. And progress there could be reversed, but if [Myanmar] succeeds, we will have gained a new partner without having fired a shot.”

In an article in The New York Times published on Aug. 15, critics pointed out Mr. Obama’s foreign policy struggles in Syria, Iraq and Ukraine as cause for “a palpable sense of disappointment with Mr. Obama’s leadership on the world stage as well.”

With 58 percent of Americans disapproving of his foreign policy, according to a June poll, Mr. Obama needs a good news tale from abroad. Myanmar may be his best bet, but claiming credit for the move toward democracy, such as it is, won’t sit well with the skeptics who assert that reforms remain incomplete and the military and its former generals are still calling the shots in a country that is far from a success story.

17 September 2014 TheIrrawaddy

Aung Zaw is the founding editor-inchief of The Irrawaddy.

US President Barack Obama at the White House in August

PHOTO: REUTERS

FEATURE | PHOTO ESSAY

Prisoners in Thailand can win respect, better conditions and time off their sentences if they defeat foreign opponents in jail-yard boxing matches

Text

Text

and Photos by

PATRICK BROWN / BANGKOK / PANOS PICTURES

PRISON FIGHT

20 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

hen you first hear the phrase “prison fight,” Hollywood films come to mind. And to some degree, you are not wrong.

This really is a case of “action” in “Amazing Thailand.”

“Prison Fight” is an organized series of Muay Thai boxing matches in which Thai inmates go up against experienced foreign boxers.

Under the scheme started last year by Thailand’s Department of Corrections, winning prisoners earn respect, better conditions and the chance to have their sentences reduced.

The foreign boxers fight for personal ambition and a small purse.

Thais say that the tradition of pardoning prisoner boxers dates back to an old legend from around 1774, when Thai boxer Nai Khanom Tom was imprisoned in Myanmar.

In that year, King Hsinbyushin (known in Thailand as King Mangra) had organized a seven-

Wday religious festival in Yangon. During the event he wanted to see how Muay Boran (the old name for Muay Thai) compared to the Myanmar boxing style, Lethwei.

According to the story, prisoner Nai Khanom Tom routed a series of Myanmar opponents. The king’s reward was to give him his freedom, and today Nai Khanom Tom is celebrated as the “father” of Muay Thai.

That old legend seemed a long way away earlier this year, when I gained access to the gritty daily realities of Section 5 in the notorious Klong Prem prison outside Bangkok.

I was told that I was the first person in thirty years to be allowed into the section with a camera. Given that the maximum security jail holds more than 5,000 inmates, I was expecting to find wardens turning a blind eye to knife fights in the yard, the odd riot and worse. In fact, I found a mix of the mundane and orderly, and the surreal.

I met the Iranian bomber who managed to blow his own legs off

21 September 2014 TheIrrawaddy

FEATURE | PHOTO ESSAY

22 TheIrrawaddy September 2014 FEATURE | PHOTO ESSAY

in downtown Bangkok in 2012. When a taxi driver refused to pick the man up on Sukhumvit 71, he threw his backpack, which was full of explosives, at the car. The bag bounced off the taxi, landed at the bomber’s feet, and you can guess the rest.

I spent around 11 hours with convicted murderers, hit men, drug dealers and drug users who had sentences ranging from 20 to 80 years.

Most of the men were covered with amazing tattoos. They create these at night when locked in their cells, using ballpoint pens, ink and a pin.

Each cell holds between three and four prisoners. There are no chairs or beds. The inmates sleep side by side, on the floor, in cells measuring approximately 1.5 meters by 3.5 meters. This includes a small and very basic bathroom area at the back. They spend 13 hours a day in this claustrophobic and confined space.

Boxing training gives purpose to prisoners’ lives. While inside Section 5, I documented the lives of prisoners who train for six hours a day, seven days a week.

For good fighters, the rewards are compelling.

Immediate benefits can include better food, a TV in their cell, and the respect of others.

Eventually, like Nai Khanom Tom under King Hsinbyushin, they may even win their freedom.

23 September 2014 TheIrrawaddy

The Ties That Bind

By AUNG ZAW / YANGON

As a young officer, Col. Myint Swe was known for his courage and his loyalty to his fellow soldiers. Always generous with those serving under him, he was fierce in battle, whether he was fighting foreign forces during WWII or an array of insurgent armies after Myanmar regained its independence in 1948.

Hailing from Pyin Oo Lwin (then known as Maymyo), he joined the army in 1942, when the country was under Japanese occupation. Three years later, he joined the uprising against his military mentors by throwing some Japanese soldiers off a train after getting them drunk while traveling to Upper Myanmar.

When he was in his 30s, he led the 104th Special Force Airborne in attacks on communist and ethnic rebels, earning a reputation for ruthlessness. Rebel leaders who surrendered admitted that their troops fled whenever they intercepted reports that the 104th was on its way.

In 1958, after a stint at the US Army Infantry School in Fort Benning, Georgia, he was assigned to the army research department—a nascent version of a homegrown Central Intelligence Agency created by Gen. Ne Win, the army leader who seized state power in 1962.

As a veteran of Gen. Ne Win’s old regiment, the 4th Burma Rifles, Col. Myint Swe enjoyed the trust of the country’s new dictator, and in 1968 he was entasked with a mopping-up

24 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

An army past has long been the businessman's best asset — but the rules of the game may be shifting

FEATURE

operation after the communist leader Thakin Than Tun, a former colleague of Myanmar’s assassinated independence hero Gen. Aung San, was himself killed by an infiltrator.

Forty years later, after a distinguished military career and a comfortable retirement, Col. Myint Swe died, leaving behind a loving family—and a legacy that continues to ripple through

the tangled web of connections that make up Myanmar’s military-business nexus.

A Soldier’s Son

Soon after his death, the highlights of Col. Myint Swe’s career were detailed in a book that included high praise from former army chief Gen. Tin Oo and late

Brig.-Gen. Aung Gyi, both of whom went on to cofound the National League for Democracy (NLD) with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi in 1988.

The publisher of that book was U Tay Za, Myanmar’s richest tycoon, and Col. Myint Swe’s youngest son.

Although it’s widely known that U Tay Za owes his fortune to his close ties to Myanmar’s former ruling generals, the depth of his connections to the military has seldom been discussed. However, as the country opens up and the hold of the so-called “cronies” comes under increasing scrutiny, it is becoming clear that some bonds are stronger than others.

This became especially apparent in July, when one of the grandsons of the late Gen. Ne Win revealed that his family’s firm had agreed to buy a majority stake in U Tay Za’s Asian Green Development (AGD) Bank.

In an emailed response to questions from The Irrawaddy, U Aye Ne Win said that the deal—which more recent reports have suggested U Tay Za is reconsidering—was based in part on his family’s special ties to that of the US-sanctioned tycoon.

“Highly reputable and prestigious though some other banking institutions in this nation undoubtedly are, we chose to establish a strategic alliance with U Tay Za and AGD Bank because we have personal connections between our families and the bank in question can provide us with an assurance of a promising future,” wrote the grandson of Myanmar’s former dictator.

If it goes ahead, the plan—which would be backed by the China National Corporation for Overseas Economic Cooperation (CCOEC), a Chinese state-owned company that has offered the Ne Win clan’s company Omni US$4.9 billion to invest as it sees fit in the Myanmar economy—would dramatically underline the hold that old elites continue to have over the country,

25 September 2014 TheIrrawaddy

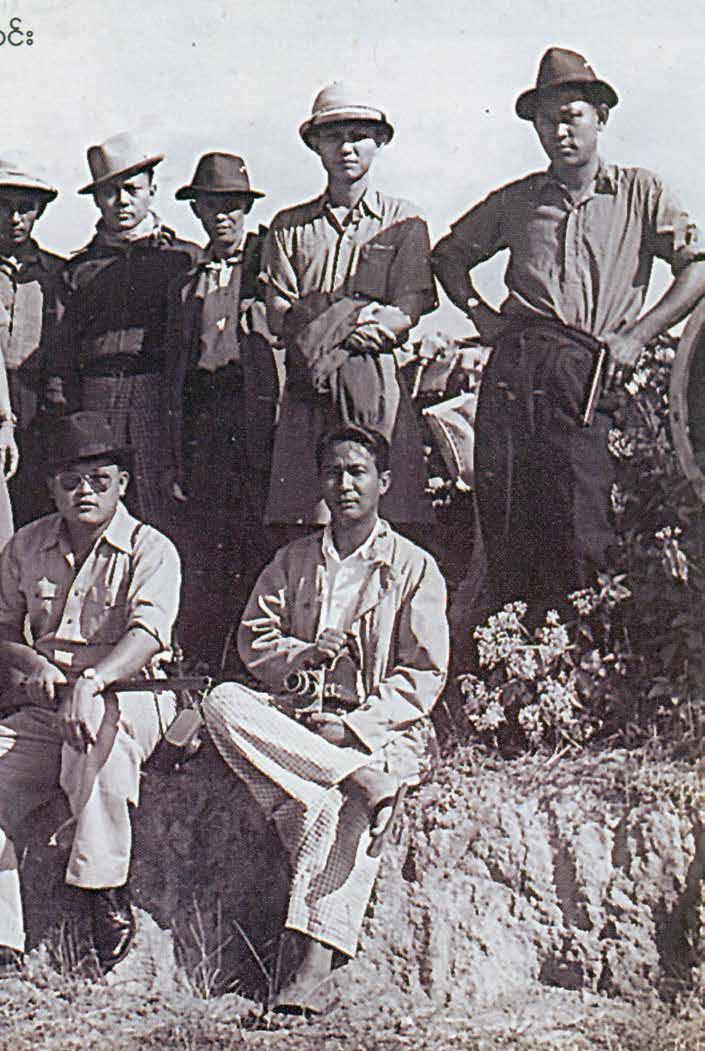

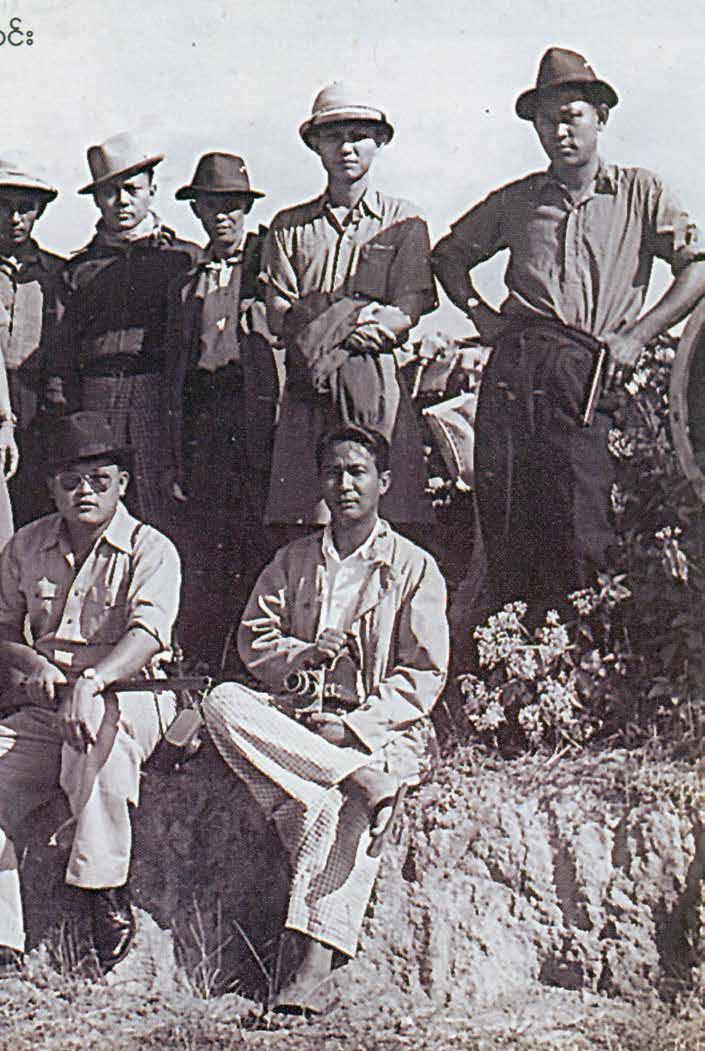

In this undated photo, Col. Myint Swe (seated, center) appears with Gen. Ne Win (standing, in sunglasses) and other members of a party traveling by the naval ship May Yu from Myeik to Kawthaung.

PHOTO: TAY ZA FAMILY ARCHIVE

and the role that personal relationships among them could play in its future development.

Frustrated

At the same time, however, the uncertainty surrounding AGD Bank highlights the continuing pressure on these elites to demonstrate greater transparency.

Preempting criticism of his family’s decision to accept money from CCOEC, U Aye Ne Win was at pains to stress that Omni had done its due diligence.

“After careful evaluation, it was brought to our knowledge that the said amount is legitimate and clean,” he said of the Chinese money—emphatically adding that his family’s assets were similarly untainted.

“In this day and age of WikiLeaks, it is highly unlikely that any fortune that is accumulated as a result of some wrongdoing will go unnoticed,” he said.

U Tay Za, however, has had to go to much greater lengths to convince those interested in doing business in Myanmar that he is someone they can safely associate with. The flamboyant tycoon, who was put on the US Treasury Department’s list of sanctioned “Specially Designated Nationals” (SDN) in 2008 for acting as an arms dealer for the former junta and otherwise supporting its rule, is known to have hired PR firms in Washington, DC, to lobby to have his name expunged from the list, to no avail.

The frustrated crony acknowledged the difficulty he’s had with cleaning up his image when he explained why he was looking to unload AGD Bank, which he established in 2010.

“We even have to provide MasterCard services later than the other banks because of US sanctions on me. Everything I do is later than the

others,” he told reporters. “The facts I have just mentioned are the reason why I want to sell my shares out.”

From Crony to Donor

In a bid to relax restrictions on his sprawling conglomerate, the Htoo Group of Companies, U Tay Za has also played the philanthropy card, donating to the NLD and, more recently, promising to give $1 million to a journalism foundation to promote better reporting (a move that raised some eyebrows in light of a libel lawsuit he launched against a local publication late last year).

But while his contributions to the country may have been enough to win him an honorary title from President U Thein Sein, U Tay Za is likely to find that the US government is not so easily impressed.

Following his first visit to Myanmar in July, Tom Malinowski, the US assistant secretary of state for democracy, human rights and labor, made it clear in an interview with The Irrawaddy that “donations to charity, while welcome, would not be taken into consideration—for this purpose, what’s important is not how they spend their money but how they make their money.”

He continued: “We will look to see SDNs sever business ties with the military, respect human rights, including by avoiding involvement in land seizures, and respect civilian rule.”

Although some see him as increasingly vulnerable (leaders of the Kachin Independence Organization, for instance, have told me that they have “warned” him about his business plans in Kachin State, and even demolished one of his helipads there), if U Tay Za can rehabilitate himself in the eyes of US policymakers—which is still a distinct possibility—he could yet emerge as one of the big winners as Myanmar’s economy opens up.

In the meantime, his status as a special class of crony—one with ties going back not just to the post-1988 junta, but also to the 1962 coup—will be more than enough to keep him in the game for some time to come.

26 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

Col. Myint Swe (standing, center) poses next to Gen. Ne Win and others in this undated photo taken in Kawthaung.

PHOTO: TAY ZA FAMILY ARCHIVE FEATURE

There is continuing pressure on business to demonstrate greater transparency

27 September 2014 TheIrrawaddy Sublime Life ... Supreme Living @Nimman-Sirimangkalajarn Soi 1 “S CONDO” Residential Condominium. Project Owner:Prattana Properties And Healthcare Co.,Ltd. Registered Capital: 50,000,000 Baht. Managing Director : Mr.Surat Leenasirimakul. Type of Project : 1 building 7 storeys with 48 Residential unit. Location : 7 Sirimangkalajran Rd. Soi1 , Muang District. Chiang Mai 50200. Land Tital Deed No: 19774. Approximate Land Area: 1-0-79 Rai. Construction Begins : October 2013. Expected Completion:June 2015. The Project will be registered as a residential condominium upon completion. Swimming pool . Fitness car park are conmon property of Condominium Juristic Person Regulations.The owner of each condominium unit will pay for common area and sinking fund expenses as stated in the Condominium Juristic Person Regulations. Exclusive only 48 Units 59 - 67 Sq.m. Start 3.77 MB. Fully Furnished & 100% Parking 053-219 300, 081-672 4214 www.scondocm.com ျပည့္စံုေသာဘဝ ... အဆင့္ျမင့္ဆံုးေနထိုင္မႈ နင္မ္မန္ - သီရိမဂၤလာလမ္းသြယ္ ၁

THAILAND CHIANG MAI

Photograph: Model Room

Making a Mockery of Democracy

The nations of Asia deserve real democracy, not a watereddown version created for the comfort of ruling elites

By BERTIL LINTNER

When the generals who previously ruled Myanmar first said in 2003 that they wanted to introduce a “discipline-flourishing democracy,” it was far from clear what they meant. Presumably, it would be different from so-called “Western-style democracy,” but beyond that, it was anybody’s guess what they had in mind.

At the time, more cynical observers suggested that the term was nothing more than a euphemism for military rule behind a democratic façade. Most likely, they said, the new, post-junta dispensation would have a constitution and an elected parliament made up of civilians, or generals and colonels who had become civilians, but the military would retain effective veto

power over any attempts to change that constitution.

All of this turned out to be true. Under Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution, the Tatmadaw, or armed forces, controls 25 percent of seats in both houses of the national legislature, and amendments require the approval of more than 75 percent of lawmakers. Other provisions also empower the

28 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

POLITIS ADVERTISEMENT

Tatmadaw’s commander-in-chief to assume direct and absolute control in the event of a national “emergency”— which could mean a popular uprising or any other threat to the military’s de facto supremacy.

Now, four years after a deeply flawed election that was boycotted by the National League for Democracy, it is more obvious than ever that the cynics were right.

It is undeniable that progress has been made. Political parties can now operate openly, and although the government has become less tolerant of the media during the past year, there is nevertheless more press freedom and freedom of expression than at any time since the military seized power in 1962.

But, as U Aung Tun, a Myanmar journalist living in the United States, pointed out in an opinion piece for Asia Times Online last year, Myanmar’s “discipline-flourishing democracy” is a “near equivalent to the term ‘illiberal democracy’ coined by US journalist and commentator Fareed Zakaria.”

The whole idea of a “disciplineflourishing democracy” is based on the notion that there could be different kinds of democracy, one suitable for

the West and another for countries outside Europe and North America. This is very similar to the idea of “Asian values” that was touted in the 1990s by then Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed and Singapore’s senior statesman Lee Kuan Yew. They argued that Asian people would have to forego personal freedoms for the sake of political stability and economic progress—and that this political model was somehow rooted in Asian cultures.

Their claim that “Western-style” democracy doesn’t suit Asian nations has since been echoed by China, which has been promoting its own philosophy of “harmony.” A commentary in the online edition of the state-run People’s Daily published in March 2005 explained what the word means in a Chinese context: “Harmony is both an ancient social ideal as well as our actual choice. Harmony will open up a broader world for future humankind and provide humanity with inexhaustible driving force for its development.”

Again, a different set of values for Asian and non-Asian cultures.

Critics would of course argue that “discipline-flourishing democracy,”

“Asian

state philosophy of “harmony” are all merely excuses for maintaining authoritarianism. And the proponents of these concepts have conveniently forgotten that the first time Asian— and at that time also African—nations declared their set of values was at a conference that was held in the

29 September 2014 TheIrrawaddy

U Win Tin, a co-founder of the National League for Democracy and a former political prisoner, was clear about his political goals.

PHOTO: STEVE TICKNER

values,” and China’s

Regional leaders argued that Asian people would have to forego personal freedoms for the sake of political stability and economic progress

POLITIS

Indonesian city of Bandung in April 1955.

That event brought together 25 Asian and African nations, among them Myanmar and other countries that had just managed to throw off the yoke of colonialism. Indonesia’s President Sukarno played host to “Third World” leaders such as India’s dignified statesman Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Egypt’s firebrand leader Gamal Abdel Nasser, Sir John Kotelawala of Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), Myanmar’s U Nu and the mercurial Prince Sihanouk of Cambodia. The Bandung conference led to the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961.

Although democracy as such was not on the agenda in Bandung, the participants were clearly opposed to the idea of one set of values for the West—which at that time meant the colonial powers—and another for the then mostly newly independent nations of Asia and Africa.

At that time, it was the Western powers that advocated the idea that there could be two sets of values, one for themselves and another for the peoples of the Third World.

Rights for All

A. Appadorai, general secretary of the Indian Council of World Affairs, wrote in a booklet published half a year after the Bandung conference that “when European people think of peace, they think of it only in the terms of Europe. In the imagination of European thinkers the world seems to be confined to areas inhabited by European races. The vast continent of Asia … containing as it does some of the most ancient civilizations, and holding the vast majority of the world’s population, does not come into the picture at all.”

rights should be the same for “all peoples everywhere.” They referred to the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, saying that there should be no double standards.

30 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

The participants at the Bandung conference made it clear that human ADVERTISEMENT

Bandung participants were opposed to the idea of one set of values for the West and another for newly independent nations.

Several decades later, however, some authoritarian leaders in Asia began to argue the opposite under the guise of “Asian values” and similar concepts. But there can be no nation, no culture in the world that does not have freedom, including personal freedom, as a fundamental value.

Ordinary Decent Values

In practice, that means that people want to be able to speak their minds without fear of arrest, and to decide for themselves who should hold power in their own country. In no culture anywhere would a parent want to see their sons and daughters dragged away in the middle of the night to a prison or torture center simply for expressing a political preference. Abhorrence of such abuses of power is universal, and any attempt to justify them in the name of “Asian values,” “harmony” or “discipline-flourishing democracy” is

an insult to the values of decent people everywhere.

I have sometimes heard the bizarre argument that democracy is an alien concept in Myanmar because “ dimokresi ” is a loanword from the English language. This is utter nonsense. Even setting aside the fact that other countries equally remote from the West have their own words for democracy—Thais, for example, use “ prachatipatai,” a word derived from Pali and Sanskrit that is similar to the terms for democracy used in Laos and Cambodia—the English language clearly has no special claim to the concept either. After all, “democracy” is borrowed from the Greek words “ demos ” and “ kratos ,” meaning “common people” and “strength” or “rule,” respectively. So according to the argument of those who don’t think Myanmar could or should be a democracy, only Greece and perhaps some parts

of India would have the right to be democratic.

It is high time to remind everyone of what was discussed and said in Bandung in 1955. There cannot be two different sets of values, one for the West and another for Asia and, presumably, the rest of the world. We are all human beings, and as such have the same need to protect ourselves from tyranny and repression, wherever it may occur or whatever shape it may take.

And it is worth remembering the words of Myanmar’s foremost advocate of democracy, the late journalist and writer U Win Tin: “What we have to do these days is make way for a new politics that can break down the mechanism of the military dictatorship, rather than being corralled into a political arena made by the government.”

The first step would be to accept the fact that cultures may be different, but certain values are undeniably universal.

31 September 2014 TheIrrawaddy

ADVERTISEMENT

Finding George Orwell in Bangkok

By EMMA LARKIN / BANGKOK

It is Saturday afternoon and I am wandering the polished hallways of Paragon, one of Bangkok’s most luxurious shopping malls, searching for signs of protest. When a frenetic series of camera flashes light up the atrium windows, I hurry down to the plaza in front of the mall toward a fast-growing throng of journalists, photographers and policemen. The crowd is so thick that the only way to find out what is happening is to squeeze my way through to the center. There, I find the source of all this commotion: a solitary protester. He sits alone amid the hubbub, solemnly holding aloft a copy of George Orwell’s novel “Nineteen Eighty-Four.”

In the immediate wake of the military coup in Thailand, which took place on May 22, hundreds of people came out to demonstrate against the overthrow of a democratically elected government. But the country’s

32 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

The dystopian masterpiece “Nineteen EightyFour” makes a surprise appearance amid the plush shopping malls of the Thai capital

Don't worry, be happy: Dancers get their make-up done backstage before a show at the Victory Monument during a military event in Bangkok on June 4. The military has staged a variety of events to “return happiness to Thai people.”

new rulers, known as the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), proved astoundingly efficient at routing out any opposition; within a matter of weeks the number of protestors had dwindled to a mere handful. As Thais who oppose the coup grapple with the everdecreasing space available to dissenters, Orwell’s dystopian novel serves as both a cautionary tale and a handbook for defiance.

As in Oceania, the omnipotent state depicted in “Nineteen Eighty-Four,” the NCPO’s ability to control those who oppose it relies primarily on fear. The ruling generals met the early peaceful protests in the capital with a disproportionate show of force, deploying some 6,000 troops to the city center. Organizers were swiftly identified and detained. Hundreds of politicians, activists and academics considered capable of inciting unrest were summoned to report to the military. Most of those detained have since been released, but only after signing an agreement not to express divisive political opinions or stir up opposition to the NCPO.

Surveillance techniques also employ the use of undercover officers. One female protester was forcibly bundled into a taxi by plainclothes policemen, while another was taken away on the back of a motorbike by a security officer sporting the familiar green armband worn by registered members of the press. Likewise, the protester outside Paragon was not arrested by the uniformed policemen who surrounded him but by a team of undercover cops that materialized from among the crowd. By using plainclothes officers in this public manner the NCPO sends a clear message: if the authorities aren’t always in uniform then you never know who the stranger standing next to you might be, or, as posters in Oceania warn, “Big Brother is Watching You.”

Perhaps even more unsettling than this blurring of lines between officialdom and civilians is the encouragement given for the general public to collude with the process. The national deputy police chief has offered 500-baht rewards (around US$15) for photographs of anti-coup activities. Government officials have also been urged to report colleagues who express ideas that might be a threat to national security. And the watchfulness continues online. While the NCPO has established working groups to scour the Internet, police warn that even to “like” something on Facebook could be used as evidence of potential insurrection against the new regime.

Two-Plus-Two

The use of “Nineteen Eighty-Four” as a symbol of protest started among a group of activists who organized public book readings to express their objection to the coup. There was nothing illegal about their silent gatherings; they never lasted longer than an hour and the number of participants in any one group was capped at four (martial law forbids public assemblies of more than five people). But even these small-scale events soon became impossible to conduct without provoking the ire of the NCPO.

The lone anti-coup demonstrator in front of Paragon found a gloomy prescience in the final pages of “Nineteen Eighty-Four.” He had gone to the mall hoping to join a group of fellow student activists but the others were arrested before they could get to the plaza. When a journalist asked if he intended to continue opposing the coup, he quoted the final lines

of “Nineteen Eighty-Four” verbatim and noted that the book does not end in victory. “It ends,” he said, “with an ordinary person succumbing to dictatorship; he is brainwashed and swallowed up by dictatorship. If everyone else is willing to give up then I’ll probably have to give up, too.”

Indeed, some would argue that the lack of sustained protest indicates most people support the coup or at least are willing to accept temporary military rule. A poll, taken in mid-June, found that over 93 percent of people were actually happy with the NCPO’s performance. But, in this enforced silence, any pronouncement on the public mood lacks authority; when criticism is prohibited, praise is surely meaningless.

So, as the NCPO imposes its singular narrative upon this chapter in Thai history and discontent is relegated to the realm of private conversation, I find myself seeking out the few signs of resistance that manage to evade the hyper-vigilant authorities. There’s been the odd snippet of graffiti (“damn coup”), swiftly whitewashed over. Someone told me about a plan to paste stickers around Bangkok that defiantly state “2+2=4,” another “Nineteen Eighty-Four” reference (“In the end the Party would announce that two and two made five, and you would have to believe it.”). And I recently heard that the Thai-language edition of “Nineteen Eighty-Four” has been flying off the bookshop shelves and is now completely out of stock.

Emma Larkin is the author of “Finding George Orwell in Burma.” A version of this story first appeared in the Nikkei Asian Review.

33 September 2014 TheIrrawaddy FEATURE

PHOTO: REUTERS

The lone anti-coup demonstrator in front of Paragon shopping mall found a gloomy prescience in the final pages of the novel.

Helping Myanmar to bridge distance

Our Services

Network Design

• Network Architecture, Optimum path from 2G/3G to LTE

• RF Planning

• Spectrum Re-farming

• RAN Network Design, Capacity Planning, Network Dimensioning

• Core Network Design

Network Optimization

• LTE Optimization

• 2G/3G Optimization / Cluster Optimization

• End-to-end Optimization

Consulting Services

• We provide business consulting services, Network Architecture options analysis, migration towards new technologies (LTE, IMS), optimized path from 2G/3G to LTE We provide consulting engineering servies

Network Performance Management

System Integration

Test Activities

Network Troubleshooting

Network Tracing

• We provide turnkey engineering services (design, optimization)

Tools

• SPT Telecommunication is versatile in the use of multiple tools, or tools that fits customer’s preference.

ဆက္သြယ္ေရးလုပ္ငန္း အမ်ားပိုင္ကုမၸဏီလီမိတက္မွ ျမန္မာျပည္သူျပည္သားအေပါင္းအား ႏႈတ္ခြန္းဆက္သပါသည္။ အားလံုးအတြက္ အၿမဲခရီးဆက္ေနမည့္ ေရႊျပည္တံခြန္ျဖစ္ပါသည္။

No. 14, Parami Residence, Parami Road, Hlaing, Yangon, Myanmar. Tel : (+95) 1-654 799, 654 800 Fax : (+95) 1-654 799 www.sptgtelecom.com

pioneer

Business

DEBATING THE ECONOMY

Economic liberalization can strengthen the resourse curse and enrich elites. For better results, one researcher proposes some controversial remedies—harness the strengths of local tycoons, and bring investment from China back into the mix.

By SIMON LEWIS / YANGON

By SIMON LEWIS / YANGON

ECONOMIC

MANUFACTURING SIGNPOSTS

PHOTO: REUTERS

POLICY

MANUFACTURING: Mattress

makes a mark

BUSINESS ECONOMY

Myanmar must enlist the country’s top tycoons and financial backing from Beijing if it wants to achieve much-needed infrastructure growth.

It might sound like a recipe for political suicide in modern Myanmar— where “the cronies” are a popular target of criticism and China is a major source of nationalist angst—but that is the prescription set out by a researcher at Singapore’s Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS).

In his July paper, “Myanmar: Between Economic Miracle and Myth,” ISEAS visiting fellow Stuart Paul Larkin sets out an alternative to what he calls “the donor lovefest and the new economic narrative.” He says that while foreign donors have been showering the government with money and barely solicited advice, a huge trade deficit has arisen (US$2.6 billion in 2013-14, according to official figures), mostly as the result of a “consumer imports boom.”

“In so far as the donor agencies cannot resist furthering the economic interests of their paymasters they are playing the game rather well,” Mr. Larkin writes, arguing that rapid economic liberalization will allow multinationals from rich countries to extract natural resources and sell goods to Myanmar consumers with minimal local gains.

Meanwhile, he argues, developing export-led industries that would create much-needed jobs has been hampered by Western countries’ emphasis on good governance and competitive tendering (without much concomitant investment), which makes the necessary infrastructure projects “difficult to get off the ground.”

The infrastructure challenge in Myanmar is massive. McKinsey Global Institute predicted last year that $320 billion of infrastructure investment would be needed between 2010 and 2030 to maintain economic growth of 8 percent a year. And it is indeed unclear who will stump up the cash,

as illustrated by the current struggle to fund a much-needed new airport for Yangon.

Poor Priorities

Larkin criticized the World Bank's International Finance Corporation for its approach in the country, which includes investments in real estate projects like a high-end hotel being built by tycoon Serge Pun.

“Real estate, especially at the high end, produces a very limited development dividend compared to infrastructure,” Mr. Larkin writes, suggesting that the arrival of China’s highly capitalized banks to the financing arena could make the IFC feel “the chill winds of competition.”

But since President U Thein Sein suspended the Myitsone hydropower dam project in 2011 amid public opposition, investment from China

36 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

has all but dried up, and other projects have felt the wrath of public sentiment against the country’s giant neighbor.

To some extent, this has been balanced by the growing presence of Japan, which has stepped in as the major foreign financer of infrastructure, notably with the Thilawa Special Economic Zone project, in which garment producers are already waiting to set up factories.

37 September 2014 TheIrrawaddy

“Real estate, especially at the high end, produces a very limited development dividend compared to infrastructure.”

—Stuart Larkin

PHOTO: REUTERS

Vehicles line up for fuel at Myanmar International Terminals Thilawa outside Yangon in April.

But Mr. Larkin calls for the Myanmar-China relationship to be revived, with China hopefully taking a “portfolio approach to financing infrastructure in Myanmar.” Chinese banks could underwrite loans or invest, he suggests, as an alternative to the shady deals conducted by government officials that marked previous Chinabacked projects.

At the same time, says Mr. Larkin, local family-owned conglomerates should be invited to “take the lead” in identifying which infrastructure projects are feasible and then be “empower[ed] with concessions.”

“After all, they are headed up by the nation’s most talented entrepreneurs,” he writes, adding that cronyism is “a political failure and not a failure in entrepreneurship.”

Mr. Larkin points out that not everyone who prospered under the old regime will continue to do so in a more open economy.

"I prefer the term 'tycoon' to 'crony', Larkin told the Irrawaddy by email. “Myanmar’s power holders will require somewhat different qualities from their tycoons than in the past for this externally financed infrastructure endeavor and not all the tycoons will manage to upgrade themselves...” he said.

“I do not think the Myanmar tycoonBeijing nexus need be ‘politically toxic’ provided it yields broad-based benefits that are explained to the general population in advance.”

Kyat Depreciation

But the political flack for any Myanmar government planning to adopt Mr. Larkin’s approach would not end there.

Mr. Larkin also recommends that the government depreciate the kyat in order to incentivize industries like the garment sector, where he sees current levels of investment as too low to create the export-led growth that has successfully pulled other Asian nations out of poverty.

He calls for the currency to be devalued “early even if the measure will be unpopular in the short term,” dismissing the significance of the “inflationary surge” that would follow as fuel and electricity prices go up.

Andrea Smurra, an economist with the Myanmar Program of the Londonbased International Growth Centre (IGC), countered that depreciation would make it more expensive to import those things needed to upgrade infrastructure and bring in the

technological improvements needed to increase rice exports, and could actually be detrimental to the garment sector as well.

“This industry [garments] currently imports everything, from thread to sewing machines,” said Mr. Smurra.

“Depreciation will make all these inputs more expensive and, by generating inflation, will eventually push the government to increase nominal minimum wages, nullifying the impact of the depreciation policy on this industry.”

Mr. Smurra also argued that inflation could trigger social unrest, pointing to the large-scale street demonstrations that have taken place each time a fractional increase in the already highly subsidized price of electricity has been proposed.

“The government does not have the fiscal resources to absorb the impact of depreciation and people will perceive their welfare as being sacrificed on the altar of the elite’s profit,” said Mr. Smurra.

“People are waiting for the famous ‘transition dividend,’ and inflation will erode all the gains accrued over the last few years. No political leader will support such a policy, and no political leader should do so.”

None of this, to Mr. Larkin’s mind, is good enough reason not to do what is economically necessary.

He characterized the concerns about the possible political fallout of his proposed policies as a question of leadership, arguing that difficult and unpopular decisions would have to be made.

“[T]he country’s politicians must rise above the temptation to pander to the prejudices of an undereducated population who are now empowered through the ballot box,” he told The Irrawaddy.

“Populism is a very real threat to Myanmar’s polity. Third rate democracies … are often worse than authoritarian regimes.”

38 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

PHOTO: REUTERS BUSINESS ECONOMY

A worker walks in Asia World port in Yangon in July.

GOLD SPONSOR:

SILVER SPONSOR:

BRONZE SPONSOR:

39 September 2014 TheIrrawaddy M.O.G.E. MOE

M.O.G.E. M.O.G.E. M.O.G.E. M.O.G.E.

Business with Bounce

What kind of factories do you have?

I have a spring-mattress factory and a furniture factory. We will also have a foam-mattress factory that will begin operation soon, and I plan to open another in Yangon in the near future. Do you only compete in the local market? Who are your main competitors?

Yes, our main market is local. This business is quite broad, with many other local manufacturers producing a variety of goods. But I don’t think in terms of competing with anyone else. I just focus on improving our products.

Mandalay-based Sein & Mya Mattress Industry Co., Ltd. is one of the country’s leading manufacturers of mattresses. Founded in 1994, it has two factories in Mandalay and seven stores nationwide, including one in Yangon. The Irrawaddy’s Kyaw Hsu Mon talked to the company’s founder U Kyaw Min about what it takes to succeed in Myanmar as an entrepreneur.

When you started your mattress business 20 years ago, how much capital did you have?

I opened this business in 1994 with just two million kyat [roughly US$2,000 at the current exchange rate] and 15 employees. I started out producing silk-cotton mattresses and related accessories. We just had a small retail

store. My wife sold the mattresses, while I sold mattress accessories door-to-door around Mandalay. The business kept growing, and now we have 200 employees at seven branches around the country. We also have two factories. This year, the president [U Thein Sein] named me the number one medium-sized manufacturer in Myanmar.

What is your share of the market? And do you plan to expand to foreign markets?

It’s always difficult to get exact figures in Myanmar, because nobody is doing proper research. It’s especially difficult to know in this business, because it includes such a wide range of companies. But if I had to guess, I would say that our share of the domestic market is about 30 percent. And yes, we plan to start exporting in the future.

Where do you get the materials and technology you need for this business?

40 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

The founder of Sein & Mya Mattress Industry Co, U Kyaw Min

ALL

COURTESY: SEIN & MYA BUSINESS INTERVIEW

A Sein & Mya manufacturing plant in Mandalay

PHOTOS

The raw materials mostly come from Thailand and China, while the technology is from Europe.

What is the key to your success?

The most important thing is quality control and constantly creating new products to meet the customers’ needs and the market situation. Customers are always our top priority.

Would you agree with those who say that local products are inferior? Are you confident that you can compete with imported goods?

As long as we maintain quality control,

we will do fine. We have a dedicated quality-control team, and all of our employees are trained to pay close attention to the quality of our products.

Are you concerned about next year, when the Asean Free Trade Agreement will go into effect? How prepared are you for the changes this will bring?

I’m pretty confident that we can compete. We already have a wellestablished brand and fully functioning factories. We can also provide better after-sales service than foreign companies. And we also sell some foreign products ourselves, including Darling spring mattresses from

Thailand and mattresses and leather beds from Baland, a US-registered company. We also import mattresses from Vietnam.

What kind of support do local manufacturers need from the government? Is the lack of infrastructure a problem for you?

The major thing we need is financial support. We need better access to credit so that we can improve our technological capacity and human resources. We’re also at a disadvantage when it comes to raw materials, because foreign companies have an easier time getting the materials they need, whereas it takes us a lot more time and effort. But mainly, I would say the biggest problem is credit, and the relatively high interest rates in this country.

42 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

“The major thing we need is credit so we can improve our technological capacity and human resources.”

—U Kyaw Min

Sein & Mya staff gather in an upbeat mood.

BUSINESS INTERVIEW

Local Companies Invest US$45 Million in Napyitaw Hotel

Executive Jets to Get Red Carpet Treatment

An executive business jet service has begun operating in and out of Yangon International Airport. The service was established by Bangkok-based entrepreneur William Heinecke, working with several Myanmar firms.

The basis of the Myanmar MJets Business Aviation Center is Mr. Heinecke’s MJets operation in Thailand, which has teamed up with Myanmar’s Wah Wah Group, founded by U Ohn Myint, and Myanma Airways.

Next to Yangon’s domestic passenger terminal, the center includes an executive lounge, business meeting facilities and separate customs and immigration clearance.

“There is a growing market for flying in investors and company CEOs on private jet charters mainly from Singapore and Bangkok,” U Ohn Myint was quoted by travel industry paper TTR Weekly as saying.

International hotel group Kempinski is confident about its prospects as it prepares to open a new luxury five-star hotel in Naypyitaw in November.

Local conglomerate Kanbawza Group and Jewellery Luck Company have invested a total of US$45 million, taking 50 percent shares each, in what will be the city’s most expensive luxury hotel, Kempinski Hotel Nay Pyi Taw, managed by Europe-based Kempinski.

The hotel will be the second hotel in Naypyitaw to be managed by an international chain. It will be built in Hotel Zone 1, where the most expensive local and international hotels are located, near the summit venue for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean).

Kempinski acquired a 50-acre compound for the 141-room hotel in late 2012, according to the hotel group’s general manager, Franck Droin.

He said renovations began in March this year on three main buildings, and that construction would be finished before the Asean Summit in November.

He added that 180 staff would work at the hotel and had already started training.

“We have renovated over the past eight months. The hotel is designed with the flair of Myanmar, with traditional handicrafts,” said Lewis Ho, the principal of Aye Lwin & Associates, which is responsible for the interior design.

Room prices will be the most expensive in the city, ranging from $220 to $4,000. Mr. Droin said he expected major clients to include state delegations visiting Myanmar, as well as NGO and business delegations. —Kyaw Hsu Mon

About 300 private jet flights will visit Myanmar this year, the paper said. —William Boot

Myanmar ‘Can Renegotiate Dam Deals’

A Chinese firm that signed deals with Myanmar’s former military rulers to build hydro dams said it could renegotiate the terms, which would see some projects supplying 90 percent of power to China, in order to allow more power for domestic consumption.

Myanmar’s unreliable power supply is undermining economic development in Asia’s second-poorest country, which is emerging from 49 years of autocratic mismanagement under military rule.

“If the new government thinks there is more power demand now in Myanmar, then of course there is no problem to meet the local demand first,” said Sun Hongshui, vice president of the Power Construction Corp of China. —Reuters

46 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

BUSINESS SIGNPOSTS

PHOTO: KYAW HSU MON / THE IRRAWADDY

The pool area of the new Kempinski Hotel in Naypyitaw.

Foreign Firms Eye Energy Advisory Role

Ten foreign legal and engineering companies have expressed interest in obtaining a consultancy contract to advise Myanmar’s Ministry of Energy on oil and gas exploration and pipeline construction.

The firms showing interest include two British legal consultancies, Jones Day and Berwin Leighton Paisner, plus Germany’s engineering business Fichtner GmbH and Texas-based Schlumberger Business Consulting, the world’s biggest oilfield services company.

The bid to appoint international advisers comes as Myanmar government agencies continue to negotiate with a number of big international oil companies over the terms of contracts on 20 offshore development blocks. The contracts were provisionally awarded last March. —William

Boot

ADVERTISEMENT Lugano – Switzerland – Phuket - Singapore We specialize in… Hotel and Tourism Developments Analyses – Concepts – Coaching – Financial plan International Marketing! We are not investors but offer a highly professional service! Contact us: Costantino E. Rossi Dipl.Hoteliers shv/vdh Senior Consultant E-Mail: rohei2@outlook.com Fax : ++41 91 994 52 68 CH Mobile : ++41 79 253 81 63 Elti Consulting & Marketing Elti Consulting & Marketing ADVERTISEMENT

China TV Series on Deng

A drama series on state television on late leader Deng Xiaoping is a rare portray

By MICHAEL MARTINA

/ BEIJING, China

China’s state television is airing a serial on late leader Deng Xiaoping, a rare portrayal of a top politician that state media have trumpeted as a sign the Communist Party is easing its grip on officials’ sensitive legacies.

The 48-part drama series chronicles a period between 1976 and 1984, when Deng began pushing China toward market reforms that ignited its transition into the world’s second largest economy.

“In recent years, China’s restricted areas of speech have obviously decreased. This series marks significant progress,” the Global Times, a tabloid owned by party mouthpiece the People’s Daily, said in an August editorial.

But the show has prompted debate about how producers will approach sensitive internal conflicts that have more or less been air brushed out of official party accounts.

More contentious than the show’s central figure is the novel appearance of actors depicting several other controversial politicians, among them the late reformist Communist Party chief Hu Yaobang, who Deng ousted.

Hu’s death in April 1989 sparked student protests centered on Tiananmen Square, a movement that later turned into pro-democracy demonstrations that were crushed by the military on orders from Deng on June 3 and 4 that year.

The timeframe of the series means it is likely to skirt Hu’s 1987 ouster and the Tiananmen crackdown, and it is unclear how it will address, if at all, the 1981 downfall at Deng’s hands of Hua Guofeng, Mao Zedong’s anointed successor.

The proof would be in the showing, said Zhang Ming, a political science professor at Renmin University in Beijing.

“[The show] is perhaps a signal that events in this era are no longer as sensitive,” Zhang added.

“If it turns out that they reveal certain things, then it could have

desensitizing benefits,” he said, referring to party battles between leaders.

In China, all broadcast media and films are pre-screened for approval and anything deemed politically sensitive is banned.

China’s government and the party have a track record of covering up bad

REGIONAL 48 TheIrrawaddy September 2014

A man looks out from a window next to a portrait of late Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping wearing military uniform in a gallery at Dafen Oil Painting Village, in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province.

Deng Raises Questions

al of a top politician, but some say it's just propaganda

or embarrassing information. Mention of events such as the Tiananmen protests remains taboo, and strict censorship limits the public’s awareness.

The myriad off-limit topics tend to funnel productions toward the drama of war, typically with programs that pit Communist armies beating

back Japanese invaders. China’s state administrator approved 69 anti-Japanese television series for production in 2012.

Despite the popularity of those shows, a series about Deng’s struggles is something of a fresh turn of events for prime-time viewers.

Some marveled that screened episodes of the show deal with the downfall of the Gang of Four, led by Mao’s widow, an event at the end of the disastrous Cultural Revolution that remains one of China’s worst political scandals.

“It appears it’s the first time the Cultural Revolution Gang of Four has been mentioned in a television drama … China really was in its most calamitous moments at that time. Intense!” one viewer wrote on the Weibo microblog.

‘Typical Propaganda’

Without question, the series has propaganda value to the party now led by President Xi Jinping, who has pledged to embark on his own economic reforms to reduce dependence on exports and state investment.

Produced by state broadcaster China Central Television in honor of Deng’s 110th birthday in August, according to the official Xinhua news

agency, the drama opens with a scene in which Deng draws water in the rain to swab his disabled son during the Cultural Revolution, when he was purged.

It comes amid a broader wave of efforts by the party to highlight Deng, with state media publishing a string of articles on the leader and previously unreleased speeches.

More than 10,000 copies of the US$19.4-million production were sent to government leaders, researchers and close connections of Deng “to seek their opinions,” the official English-language China Daily said, citing director Wu Ziniu.

Wu could not be reached for comment.

Hao Jian, a film critic and professor at Beijing Film Academy, said he was skeptical how far the series would go in loosening the narratives around China’s ruling elite.

“I know many people are reading this as a political symbol, but I don’t see it,” said Hao, who was among a handful of activists detained by authorities for more than a month in May for attending a small meeting to commemorate the 25-year anniversary of the Tiananmen protests.