Al hamdu lillah, the in-person 59th ISNA Convention ended the two-year pandemic-imposed hia tus. The crowd, consisting of thou sands of regular and first-time attendees, welcomed the chance to reconnect with friends, speakers and the bazaar.

CBS News (Sept. 3) reported that the “ISNA Convention in Rosemont [Convention Center] is the nation’s larg est gathering and networking event for the Muslim community.”

There were learning opportunities, as well as times to relax and enjoy. However, as the speakers made clear, it’s time to rethink Muslim priorities in North America. The community is rich in professionals from medicine to law and from engineering to technology. And yet it lacks enough qual ified professionals in the crucial areas that make up public communication. Young Muslims need to consider training and excelling in fields such journalism, writ ing, audiovisual communications and public speaking.

After all, we need to be skilled enough to converse on the same level fluency, knowl edge of other faiths, debate and logic as our opponents. How else can we tell our own stories from our own minds and hearts, instead of leaving such efforts to others?

Rasheed Rabbi deserves full credit for compiling the convention report despite facing difficulties. The young Rabiyah Syed also deserves credit for her reporting.

Kiran Ansari, who has returned to the pages of Islamic Horizons after a long absence, offers an interesting sideline of the convention — comments from a few organizers and attendees on what they liked about their experience and what can be improved.

Islamic Horizons invited Khalid Iqbal, a longtime MSA/ISNA leader, to coordinate this issue’s cover story on volunteerism. Despite falling seriously ill, he inspired others to provide two articles. May God restore his health and reward him.

Volunteering, an essential but oft-for gotten aspect of charity, has become restricted to donating money to the mosque or an online Muslim charity.

However, this noble endeavor has taken on a mechanical, almost sanitized, trans actional nature that fosters no connection with fellow humans or society.

To experience volunteerism’s real spirit, Muslims need to remember that the Prophet (salla Allahu ‘alayhi wa sallam) encouraged Abu Dharr (‘alayhi rahmat) to love and live with the poor (“Musnad Ahmad,” vol. 5, pg. 159). When we spend time with the socially disadvantaged, we learn about their stories and sorrows, their happiness and hopes. In short, we human ize them and understand that “There, but for the grace of God, go I.”

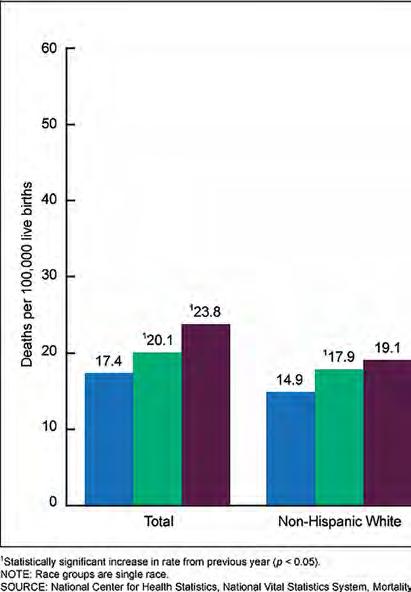

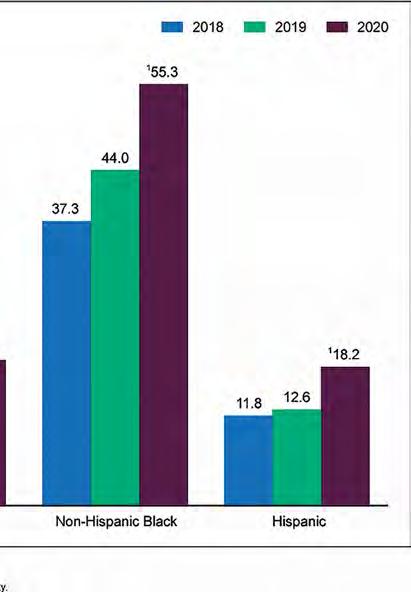

Reem Elghonimi, an author and aca demic, discusses the post-Roe v Wade situation, pointing out that while most Muslim Americans rightly support women’s reproductive rights, we must recognize a glaring omission in that narrative: According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, during childbirth Black women die from pre ventable conditions at three times the rate of white women and at a higher rate than any other ethnic or racial group (advo cate.nyc.gov/reports/).

Monia Mazigh, the prize-winning Muslim Canadian writer and journalist, shows how Islamophobia is used as a polit ical tool in Quebec, where Muslims and immigrants have become scapegoats in the province’s election cycles.

Dr. Mohammad Abdullah, a retired USDA director, asks how organic the organic food for which we pay premium prices really is.

While we were finalizing this issue, the umma lost a most illustrious scholar, Yusuf al-Qaradawi. No one questions his status as one of the 20th century’s most influential Islamic scholars — some say the Renewer of Islam (al-mujaddid).

Last September, the umma bade farewell to another remarkable person, Syed Ali Geelani, who dedicated his life to upholding the Kashmiris’ right of self-determination, after India brutally usurped their princely state on Oct. 26, 1947. They continue to be held in India’s genocidal grip. ih

The Islamic Society of North America (ISNA)

PRESIDENT Safaa Zarzour EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Basharat SaleemIqbal Unus, Chair: M. Ahmadullah Siddiqi, Saba Ali

is a bimonthly publication of the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) P.O. Box 38

Plainfield, IN 46168‑0038

Copyright @2022

All rights reserved Reproduction, in whole or in part, of this material in mechanical or electronic form without written permission is strictly prohibited.

Islamic Horizons magazine is available electronically on ProQuest’s Ethnic NewsWatch, Questia.com LexisNexis, and EBSCO Discovery Service, and is indexed by Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature. Please see your librarian for access. The name “Islamic Horizons” is protected through trademark registration ISSN 8756‑2367

Send address changes to Islamic Horizons, P.O. Box 38 Plainfield, IN 46168‑0038

Annual, domestic – $24 Canada – US$30

Overseas airmail – US$60

Contact Islamic Horizons at https://isna.net/SubscribeToIH.html

On-line: https://islamichorizons.net

For inquiries: membership@isna.net

For rates contact Islamic Horizons at (703) 742 8108, E-mail horizons@isna.net, www.isna.net

Send all correspondence and/or Letters to the Editor at: Islamic Horizons P.O. Box 38

Plainfield, IN 46168‑0038

Email: horizons@isna.net

The ISNA annual convention’s in-person return to Chicago’s Donald Stephens Convention Center marked the milestone of forfeiting our two-year digital fatigue. Many speak ers, attendees, sponsors, and others called it the best ISNA convention. With more than 175 speakers, 81 diverse sessions and workshops, 500 + bazaar booths, interfaith banquet, CSRL banquet, nightly entertain ment, hundreds of volunteers and more, this year’s ISNA convention provided a convoy of collaboration that put resilience in action beyond the published papers and discussion podiums.

CBS News (Sept. 3) described it as, “ISNA Convention in Rosemont [Convention Center] is nation’s largest gathering and net working event for the Muslim community.”

Attracting thousands of attendees, scores visited the bazaar’s 540 booths, as well the accompanying art exhibit, film festival, robotics, a women-only fashion show, gym nastics show, and matrimonial banquets. The convention ended with a volunteers’ appreciation luncheon.

Religious leaders and representatives, including ISNA president Safaa Zarzour, vice

president Magda Elkadi Saleh, Mohammad Jalaluddin (ISNA VP, Canada), Irshad Khan (president, CIOGC) and Senator Fady Qaddoura (D-Ind.) spoke during the event’s opening day event.

The convention enabled the exchange of ideas, showcased social and outreach pro grams, provided networking opportunities,

fostered interfaith interaction and good relations with other religious communities and encouraged civic engagements. Zarzour read President Joe Biden’s letter for the ISNA convention, endorsing ISNA’s efforts, on stage on Saturday night. U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona’s video message shared the work he has done alongside the Biden administration.

The heart-warming supplication of Capt. Saleha Jabeen, the first female Muslim U.S. Military chaplain, wove everyone together with the same thread of hope and commit ment to work for finding a home in the U.S.

Rashad Hussain (U.S Ambassador at-large for International Religious Freedom) highlighted some of his ongoing efforts at the government officials’ breakfast with political leaders, Homeland Security officials, and civic engagement and business leaders.

The annual Community Service Recognition Luncheon (CSRL) featured Ambassador Hussain as a keynote speaker and a virtual message from Dr. Seyyed Hossein Nasr (professor, Islamic studies, George Washington University), who received the community service recogni tion award.

Abdul Wahab received the ISNA President’s award for his outstanding ser vice to the community and to ISNA. Medal of Freedom awardee Commissioner Khizr Khan talked about his life in U.S. for the last 40 years and the importance of interfaith work and civic engagement.

Recognizing the ISNA convention’s importance, ABC, CBS, the Chicago Sun Times and other national and international media outlets lent their platforms to dissemi nate the varied lessons of instilling resilience.

The convention addressed many crit ical issues, including instilling resilience in life’s transformative stages, offering a comprehensive curriculum for diverse audiences, and motivating people to put resilience into action.

The convention’s 10 main sessions, which included a focused discussion forum, enabled the scholars to explain harnessing hope, acting with resilience and securing guidance through faith.

Waleed Basyouni (vice president, AlMaghrib Institute) urged emulating the Prophet (salla Allahu ‘alayhi wa sallam), who reflected his own optimism by changing

THE CONVENTION ADDRESSED MANY CRITICAL ISSUES INCLUDING INSTILLING RESILIENCE IN LIFE’S TRANSFORMATIVE STAGES, OFFERING A COMPREHENSIVE CURRICULUM FOR DIVERSE AUDIENCES, AND MOTIVATING PEOPLE TO PUT RESILIENCE INTO ACTION.At hand to inaugurate the event were (L-R) Asma Nizamuddin, Ashfaq Hussain, Jack Dorgan, Rosemont City trustee, Safaa Zarzour, Mir Khan, Farah Laman, Basharat Saleem, Irshad Khan.

Yathrib’s (blame and scolding) negative name to Medina (the city of God’s messenger), and noted that the fruit of prayer, when acting according to our faith, is hope. Muzammil Siddiqi, a former ISNA president, remarked that this life is a test (67:2, 29:2) and that our belief and actions will equip us to overcome them with hope and resilience. Mohammad Akram Nadwi (dean, Cambridge Islamic College; principal, Al-Salam Institute) referred to how prophets Noah, Ibrahim, Musa, ‘Isa and Muhammad harnessed hope.

The legacy of Shaykh Muhammad Shareef (founder, AlMaghrib Institute), who recently died aged 48, was commem orated during Friday’s second main session. Its speakers focused on his unique contri butions that inspired hundreds to connect their faith with their life and embrace Islam comprehensively.

Friday’s final session focused on the family, the primary place in which to ger minate the seeds of faith and sustain Islamic values. The family members’ ongoing and

mutual impacts on one another require resil iency to ward off personal stresses or strains and to engender the homogenous flow of mutual harmony and stability. Hence, parents must maintain open communication with, as well as support, their children’s self-worth.

Saturday morning’s sessions started with the discussion of extending those universal virtues of coming together for weaving a loving and supportive community.

Highlighting suicide, addiction, and other perils, Dalia Mogahed (director of research, ISPU) emphasized the need for a stronger community. To build that commu nity, Imam Mohammed Magid named three top tenets: compassion and mercy (21:107; 3:159; 55:1-4); serving the community; and consulting and collaborating with humil ity (49:13). Muzammil Siddique advocated for a mosque-centric community, for their closure during the pandemic revealed just how important they are as sources of God’s mercy and bring diverse people together.

A dedicated Saturday parallel session

(#5A) was scheduled to elaborate upon Ihsan Bagby’s (associate professor, Islamic studies, University of Kentucky) national mosque report and work with Shaykh Muhammad Nur Abdullah (former ISNA president), Nisar-ul-Haq, Mogahed and Ahmad Al-Amin (imam and religious director, Indianapolis Muslim Community Association) to realize mosque-centric com munities this vision.

While mosques arrange informal reli gious education, Islamic schools offer formal Islamic teaching. Session #4A celebrated these schools’ six-decade legacy. Saleh, who asserted that the mosque’s informal class rooms and halaqas are the base that motivates full-fledged Islamic educational institution, revealed that only 10% of Muslim American youth attend Islamic schools. Why? Because of the lack of adequate facilities and/or fund ing. She highlighted some of the common successes and concerns in this regard.

Jimmy Jones (professor and president, The Islamic Seminary of America) focused on the co-articulation of religious and ethnic/national traditions at a very young age and collaboration with non-Islamic schools, citing the joint-venture the Prophet established among the Muhajireen and the Ansar to refine both cultures.

Some consider Islamic education a for eign concept. In response, Habeeb Quadri highlighted five Islamic constructs that, he opined, need to be integrated in each school, depending on the demographics: identity, knowledge, environment, relevance and community building.

The ideas and discussions around instill ing resilience in life’s transformative stages were wrapped up beautifully in Saturday eve ning’s first session, which looked at the ethical responsibility of opposing discrimination,

racism, Islamophobia, inequality and other social perils. Mogehad shared that she found a cathedral unaffected amidst the many destroyed mosques in Bosnia during the devastating homicide and drew the lesson that “the tormentors are not our teachers.” Jamila Karim dismissed the myth that African Americans are invisible Muslims by explaining that they diligently aspire to be the “walking Quran,” an approach that we often fail to understand.

The idea of resilience reached its apex during Saturday’s final session, the conven tion’s most attended event. Nadwi explained that communities need hope to arise, as well as hard work, open minds and hearts and full of belief in God, like Prophet Ibrahim. Shaykha Ieasha Prime (resident scholar and curricu lum director, Islamic Society of Baltimore) brought home the theme by noting that our communities are already resilient, as they have survived a century of oppression, dis crimination, inequality and Islamophobia. However, she stated, we need to raise the bar.

Imam Siraj Wahaj referred to prophets Muhammad and Ibrahim to unpack the les sons of resilience and perseverance. Imam Zaid Shakir mentioned that perseverance, not running away from hardship, builds character. We must commit ourselves to God, have hope and be persistent in the face of all challenges to raise the bar of resilience.

Sunday’s session addressed the other aspects of renewing resilience. Rania Awaad (clinical associate professor of psychiatry, Stanford University School of Medicine) shared some of the research conducted during the pandemic, when 40% of average Americans experienced depression. Imam Magid explained the theo logical emphasis on thinking positive.

The last main session was dedicated to equipping the youth at an early age.

Mufti Hussain Kamani (instructor, Qalam Institute; faculty member, Qalam Seminary), Azhar Azeez (CEO, Muslim Aid USA; a former ISNA president), Prof. Hadia Mubarak (assistant professor of religion, Queens University of Charlotte; a former MSA president), Quadri and Zainedeen Abuhalimeh (president, MYNA) offered a very engaging discussion.

All of these sessions identified what

fosters and hinders resilience — a basic trait for individual survival, interpersonal relationships, and social support.

While the main sessions provided a highlevel perspective, parallel sessions offered a guided tour with all possible sub-avenues. For example, session #5A familiarized audi ences with the vision of “Ideal mosques in America” and how to sustain it. Multiple full-length sessions explored Islamic finance during a time of hardship and inflation (#5D), investing in a volatile market (#13D) and Islamic home financing (#14D).

Sessions clarified Islamophobia in the U.S. (#6A) and China (#13E), discussed if Islam is being secularized to meet contemporary needs (#5C), how Muslim narratives have been changing in the film industry (#7D), the rise of Muslim television (#14B) and start ing up a new technology firm or how tech nology’s rise can revive Quranic knowledge (#13C). Many others dealt with the strug gles of American life and global crises (e.g., Kashmir, Bangladesh, Palestine and China).

During the CSRL luncheon, Amb. Hussain stated that Muslim Americans must envision an idealistic global identity not only to become fully aware of what’s going on in the world, but also to actively address these issues as best they can.

Despite the abundant scholarship on increas ing resilience, especially post-pandemic, this convention was unique because the speakers and the attendees were able to create per sonal relationships. Recalling her extended family’s support for herself, her mother and

two sisters after her father’s demise, Mogahed explained that ease comes “with” not “after” hardship” (94:5). Such a precise discussion revealed that we often remain inactive when it comes to transcending a hardship, and therefore miss out on enjoying the subse quent ease. Once we have the correct psycho logical mindset and undertake the required action, the ease will manifest itself.

Siraj Wahhaj (imam, Masjid Al-Taqwa, Brooklyn, N.Y.) shared the story of giving shahada to his 98-year-old mother just a few days before the convention. His account unfolded the various adversities that we may encounter in this country and to prepare ourselves accordingly. After sharing personal anecdotes, Iesha Prime explained that ease is “a victory by Allah” given after hardship; the tears of peoples’ struggle is witnessed by God and with hardship there will be ease.

Similar personal stories from Amb. Ebrahim Rasool, Jamila Karim and other speakers compelled us to contemplate our personal experiences to assess if we can demonstrate adequate resilience. Such intro spection, infused with courage, will enable us to face any hardship and prepare strategies to transform stresses into resiliency. ih Rasheed Rabbi, an IT professional who earned an MA in religious studies (2016) from Hartford Seminary and is pursuing a Doctor of Ministry from Boston University, is also founder of e-Dawah (www. edawah.net) and secretary of the Association of Muslim Scientists, Engineers & Technology Professionals. He serves as a khateeb and Friday prayer leader at the ADAMS Center and is a certified Muslim chaplain at iNova Fairfax, iNovaLoudoun and Virginia’s Alexandria and Loudoun Adult Detention Centers.

*With reporting by Rabiyah Syed, a student at Naperville Central who loves photography and aspires to be a speech pathologist.

AZoom session may be a good alternative for a work meeting, but it cannot replace the energy of being surrounded by 15,000 fellow Muslims at the annual ISNA Convention. So how did people feel about attending in person after a Covid-hiatus of two years? Here’s a brief recap from some #ISNA59 attendees.

Oakbrook, Ill., resident Munazza Shahzad, who has been attending ISNA conventions for around two decades, grew up attending sessions and is now glad her adult chil dren enjoy it too. “The Friday session, ‘Sustaining Islamic Values within the Family,’ was my favorite,” she said. “Shaykh Yaser Birjas (head, Islamic Law and Theory Department, AlMaghrib Institute) and Dr. Rania Awaad (clinical associate profes sor of psychiatry, the Stanford University School of Medicine) were to the point and kept us all interested.”

On Saturday, she loved Imam Siraj Wahaj’s (imam, Al-Taqwa mosque, Brooklyn; leader, The Muslim Alliance in North America) talk about resilience, but wished that she didn’t have to wait so long to hear the main speakers. She applauded the MYNA sessions, such as Mufti Kamani (faculty member, Qalam Seminary) and

Ustadh Ubaydullah Evans’ (scholar-in-res idence, American Learning Institute for Muslims) “Quest for Sacred Knowledge.” She was glad her kids wanted to listen too. “ISNA has always been a family event, and I’m so glad it was back in Chicago and I could attend with both my parents and my kids.”

Lubna Saadeh of Riverwoods, Ill., agrees. She mostly attended MYNA ses sions with her teenaged children and was glad they could discuss the topics later as a family. “My kids loved Ustadh Ubaydullah because of his energy and clear, practical message,” said Saadeh. “My daughter had recently attended the MYNA camp, and it was wonderful to see the youth so excited. I just felt the entertainment was too much like a concert — but not in a good way.”

Out-of-state attendees also enjoyed the sessions. Philadelphians Mohammad Abdul Samad and his wife considered attending the convention in person and spending time with their daughter a dream come true. They were very pleased with the reasonable hotel rates, airport shuttle service and ideal location.

They missed Imam Omar Suleiman (founder and president, Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research), who was on

umra, but nevertheless considered the lineup very impressive. While renowned Islamic scholars like Shaykh AbdulNasir Jangda (founder, director and instructor, Qalam Seminary) always mesmerize the audience, two other speakers made a big impact on the couple. “Mr. Ajit Sahi (advo cacy director, Indian American Muslim Council; receipient of Pluralist Award 2022) addressed how Muslims are being

speakers were always comfortable. From arranging for early check-ins for interna tional guests to providing them with a quiet space to relax before the next session, the volunteers worked around the clock. One thing Nizamuddin would like to see changed is the distance between the assigned hotel rooms, for “it was tough for the volunteers to provide water to the speakers when the rooms were so far apart.”

business should participate at least once every couple of years. “The highlight for me was when one mom stopped by to share how her children have memorized the morning and evening azkaar (supplications) just by listening to Masjidal.”

Hana Rasul, 17, from Elgin, Ill., attended the bazaar for the first time as someone who could make her own shopping deci sions. “Before this, I just remember tagging along with my mom and picking up some Islamic books.”

violated in India and downtrodden in Kashmir. He won my heart when he said that he was not a Muslim, but on the side of justice,” said Abdul Samad.

The other notable speaker was Khizr Khan (founder, the Constitution Literacy and National Unity Project; member, U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom) who encouraged the youth not to shy away from applying to Ivy League schools. He said that deans of these colleges ask why they don’t see as many applications from Muslim youth. His advice: Don’t be afraid to share how your faith has shaped you and to focus your life (and college application) on how you add value to your community.

Those present also enjoyed listening to Indiana state Sen. Fady Qaddoura (D) and how he inspired the audience to become more civically engaged.

“We were a little nervous this year,” said hos pitality chair Asma Nizamuddin. “We didn’t know how many people would actually show up post-pandemic, but al-hamdu lillah it was a memorable experience for everyone.”

While it wasn’t her first-time volunteer ing with ISNA, she was honored that the convention chair asked her to be in charge of hospitality. Her team made sure that the

Kiran Malik and her family from Bartlett, Ill., had two booths at this year’s conven tion. This was their first time at ISNA, and they were excited to showcase Masjidal, their cloud-based touchscreen adhan clock. Overall, she was very pleased with the sales and connections they made with customers and other vendors. “We sell online. But the feeling you get when you hear a teary-eyed mom sharing how the clock has helped her special needs son is just another level,” said Malik. “We were able to explain how Masjidal is not your parents’ generation clunky adhan clock. Its content changes every day, and its modern design fits seamlessly with today’s aesthetic.”

The one thing Malik hopes that Muslims will learn is to stop asking for discounts. While she doesn’t want to broad-brush any segment, those who nickel-and-dime small businesses and pay full price at big box retailers should know better. “I asked them if they haggle at the Apple Store,” she joked.

Even though the bazaar layout changed unexpectedly and pre-convention commu nication could have been better, she stated that the atmosphere was collaborative among vendors. Malik believes ISNA is an experience in which every Muslim-owned

She loved the Nominal jewelry booth the most — primarily because of its setup. Everything was $20, and they had a “buy 3, get the 4th free” promo too. Tons of people were working the big booth, and traffic flowed around it without any bottlenecks. There was no waiting to be helped, and transactions were quick and easy. “It was such a no-frill setup, but it was the best customer experi ence,” Rasul remarked. She also liked the com plimentary coffee tasting at the MUHSEN booth, which was being packaged by their adult special needs program participants.

If there was one area that people were not too happy about, it was the food. From limited choices to inflated prices, there’s a lot of room for improvement. Attendees understand that event prices must be higher than regular retail because of the costs involved. But then the quality and quantity should reflect the prices. “I didn’t eat anything at the food court,” Rasul said. “I couldn’t justify a $5 water bottle and $20 plate of biryani with one small piece of meat. And since the beef tacos had run out, the chicken wasn’t even zabiha. I didn’t expect that at an Islamic convention.”

Attendees also felt that the young kids’ programs could have been better. “Having the kids at an entirely different location is extremely difficult for parents, as they some times have to leave the session for pickup,” noted Saadeh.

Shahzad agreed. Her young nieces and nephews didn’t let their parents enjoy the sessions, because there wasn’t much for chil dren of their age to do. “Logistically, having the prayer upstairs was a little awkward for some. Hopefully, next time they can have the main speakers in bigger halls like they used to,” she added. ih

Kiran Ansari, a writer and editor, resident in a Chicago suburb, enjoys a low-key life with her children, aged 20, 17 and 8.

WE WERE A LITTLE NERVOUS THIS YEAR,” SAID HOSPITALITY CHAIR ASMA NIZAMUDDIN. “WE DIDN’T KNOW HOW MANY PEOPLE WOULD ACTUALLY SHOW UP POST-PANDEMIC, BUT AL-HAMDU LILLAH IT WAS A MEMORABLE EXPERIENCE FOR EVERYONE.”

Something special happened on the second floor of Chicago’s Donald E. Stephens Convention Center this past Labor Day weekend.

There was no better place for this nation’s Muslim youth to be as the Muslim Youth of North America (MYNA; https://www. myna.org) hosted its 37th annual conven tion. MYNA presented an all-encompassing experience for the participants, from listen ing to impactful lectures delivered by some of this country’s top scholars to reuniting with friends in faith. The thousands of youth coming from different regions united for the sake of God, a truly wonderful sight to behold — especially because the entire event had been planned by the youth for the youth.

One of the global Muslim community’s biggest struggles is balancing deen with dunya. For youth, the struggle is even more convoluted due to the influences coming from their friends and family, Muslim soci ety in the U.S., American culture, as well

as their ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Each one of these pulls them in a different direction and forces them to navigate their surrounding environment’s endless hurdles to find and understand the balance. “The CuRe: Understanding Culture and Religion,” the ethos of this gathering, sought to help them with this undertaking.

This relevant theme ensured that every seat was filled during the lectures and work shops. Youth listened to speakers such as Mufti Hussain Kamani (imam, Islamic Center of Chicago; instructor, Qalam Institute), Shaykh Abdulnasir Jangda (founder and director, Qalam Institute), Shaykh Ubaydullah Evans (ALIM’s first scholar-in-residence), Shaykha Ieasha Prime (resident scholar and curriculum director, Islamic Society of Baltimore) and Dr. Dalia Mogahed (director of research, Institute for Social Policy and Understanding).

Lectures touched on subjects like the seera and Quran while addressing LGBTQ+,

feminism, toxic influences and other social issues.

The instant you entered the “MYNA Zone,” you could see that something was different. The sense of community fostered through MYNA events is unlike other youth-focused programs. Coming from across the nation, they all have different backgrounds, upbringings, experiences and interests — and yet act as if they are blood related. They had last encountered each other months — if not years — ago, but when they met it was as if no time had passed. From the long-time campers and volunteers to the first-ever attendees, all of them shared a comfort and sense of belong ing. They displayed their power throughout the convention, even during the main ISNA sessions, for their chants could be heard throughout the hall.

As the program was closing and attend ees were leaving the final session, there was a surprise waiting for them in the MYNA lounge area: a special Quran recitation ses sion by young qurra’ (reciters). The beautiful recitation of an elementary-aged boy, emu lating the recitation style of Sheikh Abdul Basit Abdul Samad, one of the most iconic modern reciters, clearly softened the audience’s hearts as they gathered to bask in the joy of listening to God’s words.

Given the current state of affairs and the trend toward the decentralization of faith, it’s vital to find and attend Muslim gather ings like this one and other MYNA events to ensure that we stick to and understand our identity and roots.

We must develop ourselves so we can lead as productive Muslims and be the present and future of the umma in this country. This convention gave us the spark; now it’s our job to provide the fuel to build and maintain a fire of passion within our souls, a passion that pushes us to make a difference in our communities. ih

AS BELIEVERS, WE OFTEN take our knowledge of God’s existence for granted. For many of us, faith in God may feel so natural that we just assume it to be the case. But belief and the quest for existential truth is not as easy for many others, especially in an increasingly faithless society, one in which believing in God is becoming equated with superstition and fantasy.

The evidence for God’s exis tence and Islam as His one true religion is grounded in emo tional, experiential, spiritual, rational, logical and scientific proofs. These proofs give us purpose, meaning, comfort and guidance throughout our lives, and the Quran and Sunna further strengthen our certainty. But how do we learn the case for God’s existence inside and out? How do we use it to relinquish any doubt and to defend our faith when questioned by others?

This winter, Muslim youth in six different locations will have the opportunity to join MYNA at one of its winter camps and explore the brandnew theme of “Proof of the Truth.” This week-long retreat will seek to ground them in faith and strengthen their conviction.

Participants will take a

deep dive into the evidence, including the miracles of the natural world, scientific discov eries, the Quran and Sunna. A host of renowned scholars and teachers will lead lectures and workshops. Past guest speak ers have included Mufti Hussain Kamani (imam, Islamic Center of Chicago; instructor, Qalam Institute), Khadeejah Bari (graduate, Qalam Institute), Imam Ahmed Alamine (Al-Fajr Mosque, Indianapolis) and Ustadha Amina Darwish (asso ciate dean for religious and spir itual life and advisor for Muslim Life, Stanford). Campers will also participate in ziplining, rock-climbing, archery, team sports and other recreational activities.

“In the most formative years of our lives, this relevant topic needs to be discussed, and MYNA’s got us covered,” Maryam Amar (outreach coordinator, MYNA Executive Committee) said. “A week full of spiritual and personal growth surrounded by forever friends. There’s no way I am going to miss out on this, and there’s no way you should either.”

Gain beneficial and applica ble knowledge. Ground your self in your faith. Experience the joy of Islamic companionship. Register today at www.myna. org/camps. ih

The beauty of our religion is in its simplicity.

For one week during July and August, over 300 youth from all over the nation came to this realization, thanks to MYNA’s six regional summer retreats. Rooted in the theme “Back to Basics,” these events allowed campers to take a step back and revisit Islam’s roots and learn about the foundations on which it was built.

Ranging from the Islam’s pil lars to iman and ihsan, campers gained knowledge through lec tures, preparing short talks with our scholars’ assistance, as well as cooperating with other camp ers in skits and creative poster workshops to express what they learned. Speakers and staff graded their projects not only for creativity and aesthetics, but also for their content’s accuracy. This ensured that all campers left every work shop with another lesson learned.

In more than half of MYNA’s camps, youth were joined by a resident scholar. Imam Mohamed Herbert, Ustadha Faduma Warsame (chaplain and Muslim Life advisor, University of Minnesota), Imam Ahmed Alamine and Ustadha Khadeejah Bari stayed with camp ers throughout the event, enabling the latter to build a relationship with renowned scholars and open up to them about their questions and concerns.

Youth were also joined by

Mufti Abdulwahab Waheed (a co-founder, Miftaah Institute; a co-founder and director, Michigan Islamic Institute), Ustadha Jannah Sultan (resident scholar, Tarbiya Institute), Ustadha Amina Darwish, Dr. Bilal Ansari (faculty associate in Muslim Pastoral Theology; co-director of MA in chaplaincy; director of Islamic chaplaincy program, Hartford International University for Religion and Peace), Shaykh Mohammed Bemat (coun selor/imam, ISNA), Mufti Hussain Kamani and others.

Campers also got to engage in recreational activities and build new friendships while participat ing in archery, ziplining, hiking, tomahawk and even canoeing. And what adds to all of these events is the MYNA environment. Campers learned they can do so much during the day, still pray every salah on time and wake up for fajr — even tahajjud ! Detached from their smartphones, they made new friends who have similar interests.

“I don’t know where I would’ve been without MYNA,” Mahmoud El-Malah said. “I’ve been going to MYNA camps since I was 12, and I experience every camp as if it’s my first camp. MYNA played a vital role in my upbringing and my childhood. It taught me that no matter where I live, I can always find friends that can bring me closer to Allah. Every single camp has taught me a new aspect of our religion.” ih

Muslim students in New York’s Brent wood district are being served halal food in school cafeterias starting this school year in September. The Brentwood Union Free School District unanimously passed a res olution on July 20 to offer halal food in the district’s 19 cafeterias.

Trustee Hassan Ahmed, the first Muslim and Pakistani-American official elected in Suffolk County, introduced the resolution to include halal dietary options. He estimates that 1,000+ Muslim families live in the dis trict, which has two mosques.

The Atlantic City (N.J.) school district began serving halal food at several elemen tary schools and the high school during March 2021.

San Francisco’s Arab Resource and Orga nizing Center celebrated the decision. Exec utive Director Lara Kiswani proclaimed: “This resolution demonstrates that racial justice is not just a value. But something that must be an everyday priority and practice in San Francisco Unified School District.”

Supporters of the resolution say it will make Muslim students feel more included in public schools and prevent them from miss ing important school deadlines because of their religious observance. The measure also “foster[s] an environment of diversity and tolerance,” according to the resolution’s text.

Board members Kevine Boggess, Jenny Lam, Matt Alexander and Lisa Weiss man-Ward voted in favor of the measure; Ann Hsu voted against it.

Omar Farah assumed his post as ex ecutive director of Muslim Advocates during August. In his previous po sition — senior staff attor ney and associate director of strategic initiatives at the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), a cutting-edge national le gal advocacy organization — he worked on some of the most trenchant challenges facing Muslim American communities to day: litigating against post-9/11 abuses of power by representing Muslims detained at Guantánamo Bay and building institu tional bulwarks against white nationalism and institutional racism by helping establish and expand CCR’s presence in the South.

all students demonstrate proficiency in foundational reading skills by recognizing a school corporation (Tri-Township) that has achieved a 100% districtwide passing rate on the 2022 IREAD-3 assessment. It also recognizes large and small elemen tary schools that have achieved the highest schoolwide IREAD-3 pass rate percentage, along with the highest pass rate across all student populations.

Dr. Katie Jenner, the state’s education sec retary, said, “Indiana’s first-ever Educational Excellence Awards Gala brought together some of our most impactful educators and school leaders, whose daily work is helping countless students to ignite their own pur pose, know their value and understand the possibilities for their life’s path. We know that real impact for students happens at the edu cator-level, and our team remains dedicated to supporting educators and amplifying their good work.”

Grants must be used to sustain and ex pand the school’s current impactful pro gramming, support teachers who lead this work, as well as mentor other schools to drive additional innovative strategies through a community of practice.

The San Francisco Unified School District’s (SFUSD) school board voted on Aug. 6 to recognize Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Ad ha as official holidays and close schools and administrative offices on those days begin ning in the 2023-24 school year.

If the holidays fall on a weekend, school will not be in session either the day before or after.

A 2013 demographic study estimated that about 250,000 Muslims live in the Bay Area, of which about 3% live in San Francisco. The study, commissioned by the One Nation Bay Area Project, said the city’s Tenderloin neighborhood in particular had concentra tions of Yemeni, Iraqi, Moroccan, Algerian, Indonesian and Malaysian Muslims.

A graduate of Columbia University and Georgetown University Law School, Farah had partnered with Muslim Advocates on the landmark lawsuit that helped shut down the NYPD’s unconstitutional surveillance program targeting New Jersey’s Muslims.

Voting 5-0-1 on Aug. 23, the Anaheim City Council fulfilled an at least two-dec ades-long demand by officially recognizing an area of Brookhurst Street as Little Arabia — its nickname for years.

Perhaps the nation’s first formal Arab American cultural district, its leaders, business owners and community members had been calling upon councilmembers to bestow this designation.

The first-ever Indiana Educational Excellence Awards, held on Sept. 9, recog nized Eman Schools of Fishers, Ind., with its Excellence in Early Literacy award. It comes with a $170,000 award grant.

This award focuses on ensuring that

Rashad Al-Dabbagh (founder, Arab American Civic Council), who spearheaded the push for years, believes that this move will help uplift their small businesses, sup port the immigrant families and honor this community.

According to the OC Weekly (2012), by the 1980s white flight had left the area mostly abandoned or replaced with seedy businesses.

Little Arabia, which grew significantly in the 1990s due to the arrival of Arab immigrants, is now home to thousands of Arab-Americans hailing predominantly from Egypt, Syria, Lebanon and Palestine. Local business leaders began buying distressed homes and selling them to these immigrants. They also bought plazas and office buildings, as well as recruited merchants to start up new businesses in West Anaheim.

During his 2014 State of the City address, an event held at the time by the Anaheim Chamber of Commerce, Anaheim mayor Tom Tait encouraged the 600+ attendees to visit the district and dine at authentic Arabic restaurants.

A study, which is expected to take 6-9 months to complete, could potentially lead to the expansion of Little Arabia’s boundaries.

Little Arabia residents believe that it will not only acknowledge their contributions to the city and make them feel appreciated, but also help bring in more business.

the Center’s lawsuit, a judge ordered the two sides to work together to establish the city’s first mosque.

The mosque was legally represented by the Michigan chapter of the Council on American Islamic Relations (CAIR-MI). “Litigation, however, is still pending regard ing the City Council’s refusal to pay damages to the community for legal fees and violating its civil rights,” CAIR-MI said. The mosque is asking for $1.9 million.

The building housing the mosque is roughly 21,000 sq. ft. in size, with a 11,000 sq. ft. prayer area. The parking lot accommo dates some 155 cars. The project has already cost more than $3 million.

establish The Kanbour Chair of Gynecology.

To advance continued research and schol arly work in the field of gynecology, Dr. Anisa I. Kanbour, a distinguished pathologist and former Medical Director of the Anisa I. Kan bour School of Cytology, made a transforma tional gift to establish The Kanbour Chair of Gynecology. This generous endowment will provide a continuous stream of income to support gynecological research, specifically in the lower genital tract.

Kanbor graduated from Baghdad Med ical College in 1957 and practiced obstetrics and gynecology for several years in Iraq. During a 1964 trip to the U.S. to visit fam ily, she applied for — and received — a scholarship that enabled her to attend the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Medicine. She completed a pa thology residency at Philadelphia General Hospital and came to Magee-Women’s Hos pital in 1969 for a gynecologic pathology fellowship. She remained there until her retirement in January 2013. Over the years, she established herself as an expert in the field of pathology and cytology.

Troy, Mich. inaugurated its first mosque, the Adam Community Center, on Sept. 17, with Mayor Ethan Baker, Shaykh Muhammad Al-Masmari (imam and kha tib, Muslim Unity Center, Bloomfield Hills, Mich.), Shaykh Mustapha Elturk (ameer, the Islamic Organization of North Ameri ca) and Dawud Walid (executive director, CAIR-MI).

Until now, the large ethnically and reli giously diverse Metro Detroit city of 80,000+ residents had churches, temples and a syna gogue but no mosque, despite its large and recognized Muslim population.

The building is a former restaurant already zoned for assembly use. However, the city refused to provide the Center with a variance to allow it to be used for reli gious use.

The refusal resulted in two lawsuits filed in U.S. District Court in Detroit: one by the U.S. Department of Justice in 2019 that claimed discrimination in the city’s zoning, and another filed by the Center itself. The Justice Department supports the mosque’s argument to be treated equally, and the court ruled in its favor during March. In

Muslims on Pittsburgh’s North Side broke ground for their Light of the Age Mosque — the city’s first mosque to be built from the ground up — on Aug. 24. They have spent the last two decades praying in a rented building near Allegheny General Hospital.

A large portion of the mosque’s fund ing comes from the late Anisa I. Kanbour, a local physician and longtime supporter of Pittsburgh’s Muslim community who willed $1.5 million to establish the building in the city’s limits. Ever since the 1970s, her brother Fouad Kanbour told the gathering, she had wanted to build a mosque in Pittsburgh.

Imam Hamza Perez, a co-founder of the mosque, told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette on Aug. 24 that he had a dream before receiv ing the funding, in which he came upon a mosque where all the doors except one were locked.

The Manchester Citizens Corporation, a neighborhood group, and its executive director LaShawn Burton-Faulk also helped bring the mosque into the neighborhood.

The late Iraq-born physician (Baghdad Medical College ‘57) endowed The Anisa I. Kanbour School of Cytopathology/Univer sity Health Center of Pittsburgh at Magee Women’s Hospital, Pittsburgh — one of the oldest cytotechnology schools in the country — and also made the transformational gift to

Imam Shane Atkinson (associate chap lain for Muslim life, Elon University) has been awarded a grant from the “Islam on the Edges” program by Shenandoah University’s Center for Is lam in the Contemporary World. The grant will help fund research on the diverse facets of Islam and the Muslim community, including geography, doctrine, culture, language, history and civilizations.

Atkinson’s project, “Where the Mountains Meet: The Devotional Arts of Sacred Harp and Sufi Dhikr,” will focus on the overlap between “sacred harp,” a style of Appalachian gospel music, and the Sufi chants of the Qadiri Sufi order of the Caucasus. He will explore the unique characteristics and shared traits of these vocal and spiritual worship forms while promoting their preservation and modern reconfiguration through a self-composed piece utilizing elements of both styles.

Atkinson, born to a Mississippi South ern Baptist family, feels that this project is a natural expression of what it means to be a Muslim from the Deep South and is honored and excited to be chosen for the grant.

“It’s very encouraging that the broader society is having a more nuanced under standing of who Muslims are,” Atkinson said. “We are not a monolith.”

In addition to his research and work at Elon, Atkinson has been featured in the Harvard University Pluralism Project and starred in the documentary “Redneck Muslim,” directed by Jennifer Taylor. The film shares Atkinson’s story as a convert while staying true to his southern identity and combatting white supremacy. ih

Salma Hussein (MSW, University of Minnesota ’13, Ed.D., Hamline Univ., ’24, LICSW), a K-12 school administrator who has called Minnesota home since migrating from Somalia in 1996, was appointed principal at Gideon Pond Ele mentary in The Burnsville-Eagan-Savage school district.

The 2021 Bush Fellowship recipient, who is pursuing her educational doctorate, also served as board member of The Confeder ation of Somali Community in Minnesota (2015–18) and is the state’s first Somali female principal.

Hussein says, “I had no intention of becoming Minnesota’s first Somali female principal, let alone making history. I am called to educate and foster the minds and hearts of our young people. The work contin ues to facilitate love and strength-based sys tems change. With love, everything is better.”

In high school, she and her sister Fatima founded Girls Initiative in Recreation and Leisurely Sport (GIRLS), a nonprofit orga nization that has blossomed into a cross-cul tural community and safe space for women and girls to exercise and play sports.

Shaykha Ieasha Prime (resident scholar and curriculum director, Islamic Society of Baltimore) is a renowned speaker and educator who has received several scholarly licenses (ijaza). She studied Arabic and Quran at Cairo’s Fajr Institute and then moved to Hadramawt, Yemen, where she studied aqeedah, the Quran, Hadith, Arabic, fiqh and Islamic law, along with “Purification of the Heart” and more at Dar al-Zahra, an Islamic university for women.

A convert for 20+ years, she has spent most of her life as an educator and activist. In addition to being a wife and the mother of three children, Prime been involved in

Dr. Berthena Nabaa-McKinney (D), the first Muslim elected to the board, was sworn in on Aug. 31 to represent District 4 on the Metro Nashville (Tenn.) Board of Education.

In 2020, the Metro Council appointed this former MNPS teacher fill the gap left by the death of Chair Anna Shepherd. On Aug.4, she was elected for the first time.

Nabaa-McKinney owns Nabaa Con sulting, LLC, an educational consulting firm specializing in school improvement for Early Learning and K-12 schools.

Prior to her consultant role, Nabaa-McKinney was the principal at Nashville International Academy and led the school through its restructuring effort to achieve its first-time accreditation. She also led and served on school and district accreditation teams across the state.

During her time at MNPS, Nabaa-McKinney worked at Antioch and Cane Ridge high schools in vari ous roles, including chemistry teacher, science department chair, freshman academy lead and ACT coordinator.

the founding and leadership of numerous Islamic organizations. She remains passion ate about the courses she teaches on tradi tional knowledge, the challenges of race and gender in the Muslim community, as well as spirituality.

Until her recent appointment, she was a commissioner on the Metro Action Commission. Currently, she sits on the boards of the ACLU-TN, PENCIL and Muslim American Cultural Center. She is an alumnus of L’Evate, formerly Leadership Donelson-Hermitage, Class of 2016, and a former co-chair of their youth leadership program, YELL. ih

of the impact made by MY Project USA in Central Ohio in just seven years means a lot to me personally.”

“We celebrate these inspiring individuals who have used their decades of life experi ence to give back in a meaningful way, to be leaders in their communities and to create a better future for us all,” added AARP CEO Jo Ann Jenkins.

Each winner received $50,000 for their nonprofit organizations. The AARP Inspire Award provides an additional $10,000 to the organization of a Purpose Prize winner based on the public’s vote.

The 2023 AARP Purpose Prize winners include Zerqa Abid, founder and executive director of MY Project USA (Columbus, Ohio), which protects youth from drugs, gangs and human trafficking by empowering them through sports, social services and civic engagement.

The awards ceremony was held Oct. 25 in Washington, D.C. The annual prize is given to five individuals, aged 50 and over, who are using their knowledge and life experience to solve challenging social problems.

Abid said, “This national recognition

Azmat Khan, a Pulitzer Center board member, was honored with the 2022 Cat alyst Award on Oct. 11 by the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press.

According to the Reporters Committee, Khan’s “inves tigations for The New York Times Magazine, the PBS series FRONTLINE, and BuzzFeed’s investigations team have exposed major myths of war, prompting widespread poli cy impact from Washington to Kabul, and winning nearly a dozen awards.”

Khan and her New York Times team won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting for their Civilian Casualty Files, an investigation into civilian deaths result ing from U.S. airstrikes in the Middle East. Khan was named to the Pulitzer Center board earlier this year.

Dr. Hanan Almasri took charge as principal of the Islamic Academy of North Texas (IANT) Quranic Academy, Richardson.

With 25+ years of experience in the educa tional field, Almasri has served in various roles, among them a K-12 Quran, Islamic studies, and Arabic teacher; an elementary school teacher; a high school academic counselor a secondary dean of academics; and a middle and high school principal.

She holds a master’s and doctoral degree in educational leadership and policy studies. Her research focuses on improving the reten tion of highly qualified teachers in Islamic schools, thereby improving the quality of education for the student population. She defended her dissertation, “The High Cost of Leaving: Veteran Teacher Retention in Islamic Schools,” during 2022.

She additionally maintains several ed ucator certificates, including Texas Prin cipal Certification: Early Childhood–High School, Early Childhood–6th Grade General Education Certification, Early Childhood–High School ESL Certification and Early Childhood Special Education Certification. She has a bachelor’s degree in interdisciplin ary studies in PK–6 education.

teams include strained silicon, High-K met al gate, FinFet transistors and, most recently, RibbonFET transistors. It added that his contribution to semiconductor technology has been enormous.

ADAMS’ Tahfeedh ul Quran Program (Sterling, Va. branch) announced that Hafidh Imran Boufalla, 12, son of Said Boufalla and Aicha Abdellaoui, completed his hifdh program. He started his journey in September 2019 and finished it in May of this year. Also, Hafidh Ashaj Hossain, 14, son Syed and Mumtahina Hossain, completed his hifdh journey on Aug. 22, which he had started in Sept. 2017. ih

His first book, “Geology and Hazardous Waste Management” (Prentice-Hall, 1996), was used as a textbook at many U.S. and overseas universities and received the Asso ciation of Environmental and Engineering Geologists’ prestigious Holdredge Award in 1998.

Hasan (professor emeritus, environmen tal geology, University of Missouri-Kansas City) is a two-time recipient of the Fulbright Senior Scholar Award (2016, Qatar Univer sity; 2020, University of Jordan) and the only environmental — as well as Muslim — sci entist in the world who has singly authored two college textbooks in this field.

Prof. Syed Eqbal Hasan was invited by the University of Missouri-Kansas City’s Department of Earth & Environmental Sci ences to teach a course in waste management during the fall semester, which began in August. This call came one week after John Wiley & Sons published his new college text book, “Introduction to Waste Management” (August 2022). This is his second textbook in the field of environmental science.

A delegation from the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (MUIS) led by Zalman Ali, director, halal development, and comprising Nurul Hidayah Abubakar, assistant director, halal certification, Diana Husna Beetsma, head of standards and development and Sharifuddin M. Ali, head, halal supply network, visited the office of Islamic Services of America (ISA), in Cedar Rapids, Iowa on Sept. 21.

Muhammad (“Mo”) Arsalan Haq, a Pa kistani-American entrepreneur in Kansas City who has extensive experience in the restau rants' management, joined the AMC Theatres as the vice president, food and beverage.

AMC Theaters is the largest movie exhi bition company in the world with approxi mately 1,000 theaters and more than 11,000 screens across the globe serving nearly 350 million guests annually. ih

Tahir Ghani was named 2022 Inventor of the Year at Intel, where he is senior fellow and director of process pathfinding in the Technology Development Group.

In his 28-year career at Intel, Ghani, of ten called “Mr. Transistor,” has filed more than 1,000 patents and led teams respon sible for some of the most revolutionary changes in transistors. An Aug. 17 Intel handout stated that innovations from his

ISA, which has been providing halal certification and auditing to companies, the community, and the halal industry for over 45 years, is one of a few U.S. halal certifiers recognized by MUIS for the Singa pore market.

Zalman Ali said, “Through the briefing and engagement with the ISA team, we have found that ISA is aligned to MUIS’s commitment to Halal integrity and has put in place a Halal quality assurance system that meets MUIS’s standards."

The delegation also visited the Mother Mosque of America, a historical land mark as the nation’s oldest standing purpose-built mosque, and the Islamic Center of Cedar Rapids. ih

Muslim immigrants in the West, especially in North America, have done an incredible job of integrating into the mainstream. Unlike their non-immigrant counterparts, some of them have fast-tracked their way over the course of just two or three gener ations into such respectable professions as medicine, law and engineering. They have also shown their willingness to embrace modernity.

Unfortunately, they traded a pervasively Islamic society for one that is philosoph ically at odds with Islamic principles. As a result, they separated their spiritual and worldly selves and made their worship a private transaction between themselves and the Creator. This self-made bubble has

blinded them to modernity’s immense spir itual and psychological toll — rising levels of anxiety, depression, despair and other mental illnesses.

Muslims who wish to succeed as Muslims in the midst of modernity must reconfigure their understanding of worship. But how does one encourage them to think of Islam as a transformative rather than a transactional force? One way would be to understand that the pillars of Islam are less of an end goal unto themselves and more of a means to attain goals like humility, selflessness and God’s pleasure.

Volunteering, an essential but oft-forgot ten aspect of charity, has become restricted to donating money to the mosque or an online Muslim charity. However, this noble

endeavor has taken on a mechanical, almost sanitized, transactional nature that fosters no connection with fellow humans or society. Thus, how can one understand the hadith that all Muslims are like one body (“Sahih al-Bukhari,” 6011)?

The Prophet (salla Allahu ‘alayhi wa sallam) encouraged Abu Dharr (‘alayhi rahmat) to love and live with the poor (“Musnad Ahmad,” vol. 5, pg. 159). When we spend time with the socially disadvan taged, we learn about their stories and sor rows, their happiness and hopes. In short, we humanize them and understand that “There, but for the grace of God, go I.”

Muslim high school and college stu dents often volunteer, fueled by their desire to encourage good and forbid evil, at their

local shelters or with Muslim charities. Unfortunately, full-time jobs, marriage and families often limit such activities to week end Islamic schools or mosque activities. Muslims need to reignite and extend their youthful passion to other opportunities by serving humanity and, ultimately, connecting with and conveying the prophetic example to our youth. Remember that the Prophet’s Mosque also served as a soup kitchen for the Companions of the Porch (Ahl al-Suffa).

in the inner-city by organizing for social change, cultivating the arts, and operating a holistic health center….” Among other ser vices, it operates food banks and advocates for local businesses and reforming legisla tion that targets people of color. In 2016, a chapter was opened in Atlanta’s West End neighborhood.

➤ Islah LA (https://islahla.org/) serves the Los Angeles community by offering a platform on which inner-city Muslims can

➤ Tayba Foundation (https://www. taybafoundation.org/) serves “all people affected by incarceration, does not discrim inate on the basis of race, color, religion or national and ethnic origin in administration of its educational and admission policies…”

➤ Ek Plate Biryani (https://ekplatebir yani.com/about-us/) comprises a Canadian group of volunteers. Literally meaning “One Plate of Biryani,” it highlights the importance of small consistent change. They moved from “cooked meals to food rations and school lunches, and then on towards lasting clean water solutions and sustainable income projects…”

➤ Paani Project (https://www.paani project.org/), founded by a few University of Michigan students, tackles Pakistan’s water crisis by building wells, supplying medical supply kits and hope. It members are also active in other water-scarce countries.

As the saying goes, charity begins at home. But it shouldn’t end there, for there are endless ways to follow the Prophet’s and his Companions’ example. Anas ibn Malik (‘alayhi rahmat) narrated that the Prophet said, “Good deeds done for people protect those who did them from evil fates, harm and destruction. The people of goodness in the world are the people of goodness in the Hereafter” (“Shu’ab al-Iman,” 7704).

Listed below are some lesser-known organizations that tackle unique issues.

➤ Muhsen (https://muhsen.org/) pro vides resources for differently abled people. It seeks to “establish an inclusive and accessible environment for individuals with disabilities and their families … advocate and educate, conduct training, and implement programs and services across North America to improve the experience within mosques, conventions, related classes and events, as well as to engen der a positive and welcoming community for persons with disabilities….” Its staff has made large inroads in initiating conversations and acknowledging the challenges faced by this formerly ignored community.

➤ IMAN (https://www.imancentral. org/chicago/), founded 25 years ago, advo cates for and offers resources to Chicago’s economically disadvantaged inner-city population. “The Inner-City Muslim Action Network (IMAN) is a community organiza tion that fosters health, wellness and healing

address their growing needs. It also seeks to “renew faith, education, unity, family, civic engagement, and economic empowerment in South Los Angeles.”

➤ Nisa Helpline (https://nisahelpline. com/) and Wafa House (https://www.wafa house.org/) focus on women’s concerns, including domestic abuse. Canada-based Nisa Helpline offers “peer-to-peer coun seling, support in creating action plans, referrals, emotional and spiritual support and encouragement to women … well-being of Muslim women in North America and empower them with the tools necessary to lead self-sufficient and dignified lives….”

New Jersey-based Wafa House “caters to the needs of the Middle Eastern and South Asian (survivors) … reunit(es) children with their biological parents after displacement or removal from their homes … counsel ing services and teach(ing) active parent ing skills…” and much more. The North American community needs many more such organizations to address the needs of Muslims who need mental health support and have survived domestic violence.

➤ Ojala Foundation (https://www.ojala foundation.org/) supports Illinois’ Latino Muslims via clothing and food drives and offers “spaces where our brothers and sisters can congregate and feel a sense of belong ing … yearly Eid celebrations for the entire family … iftar da‘wah…”

➤ Islamic Social Services of South Jersey (https://www.isssj.org/) advocates for women to “create sustainable change for themselves, their families, and com munities.” Participants team up with local sister organizations and during emergency situations like the recent floods in Pakistan.

➤ Community SJP’s (https://www.csfnj. org/) dedicated volunteers arranges food drives, care packages and other initiatives for the South Jersey–Philadelphia area.

➤ Care and Share Foundation https:// shareandcare.org/) provides meals, care packages, funeral services and other services.

We have seen what is possible through the three Ds of du‘a, drive and determination. The ideas listed below highlight how we can incorporate the Prophetic examples in our communities:

➤ Hobby clubs for Muslim and non-Muslim youth. Hiking, arts and crafts, reading and other hobbies can be used to encourage one’s understanding of fitra and our relationship with the Divine. After all, children are souls before their bodies and thus finely attuned to their fitra

➤ Volunteering at hospitals and/or nursing homes. Imam al Qurtubi (‘alayhi rahmat; d. 1273) mentions that visiting the sick and the dying softens the heart (“Reminder of the Conditions of the Dead and the Matters of the Heart”). We don’t know how showing such compassion in their time of greatest need might affect them or testify for us on the Day of Judgement (“Sahih Muslim,” 2568).

MUSLIMS WHO WISH TO SUCCEED AS MUSLIMS IN THE MIDST OF MODERNITY MUST RECONFIGURE THEIR UNDERSTANDING OF WORSHIP. BUT HOW DOES ONE ENCOURAGE THEM TO THINK OF ISLAM AS A TRANSFORMATIVE RATHER THAN A TRANSACTIONAL FORCE?

➤ Outreach programs to integrate converts. Converts are often left to fend for themselves after losing the support of their former communities and being forgotten by Muslim groups. Our great est strengths are our unity and the ties of Islam. What better event is there than to welcome our new brothers and sisters in faith?

➤ Fostering relationships between inner-city and resource-rich suburban Muslim communities. We must address the elephant in the room: Economically successful immigrant communities have traditionally ignored the socially disad vantaged African American and Latino Muslims.

➤ Clubs that mentor Muslim youth in academic and social subjects. As our youth face ideologies that are increas ingly at odds with our principles, we should offer them a wholistic support system that anticipates and addresses their needs.

➤ Clubs that help integrate new immigrants. We can provide them with networking opportunities and mentor ship, just as the Muhajireen did for the Ansar.

The Prophet said: “God does not look at your outward appearance and your goods. He looks only at your hearts and your deeds” (“Sahih Muslim,” Birr, 33).

These investments in our commu nity and our eternity inherently come with a high price tag: Volunteers often face judgment and anger from both their community and the people they are trying to help. As disappointing as this can be, we must remind ourselves that our undertaking is with God, the Giver of all things, and not His Creation. Accepting this attribute comforts us in the knowledge that God knows what we do and what’s our hearts, because “God is ever Appreciative, All-Knowing” (4:147).

One of the Saleheen (pious predeces sors) has said, “The people of the world are truly of the poor, as they leave the world without finding the jewel therein: the knowledge of God.” This knowledge is the emptiness we feel in our hearts, that yearning for something deeper even when we have “everything.” May God make us one of those who seek His pleasure until we meet Him. ih

One evening while at a social gathering, Sumbla Hasan and her friends were talking about the recent influx of Syrian refugees that had settled in their area. Hasan discovered that many of the new arrivals in Detroit weren’t receiving appropriate assistance from reset tlement organizations, so she volunteered her garage to store the donated furniture.

While volunteering, she was deeply dis turbed by their living conditions, lack of basic necessities and inability to provide for themselves. After discussing the need for an organized effort, she and her friends cre ated a WhatsApp group to encourage others to join their grassroot initiative. Naming this group chat Community Helpers (CH; https://communityhelpersusa.org/), she began her career in service. Within a few days, about 150 like-minded volunteers were assigned to various areas in which the refu gees were being placed.

Hasan, along with other amazing vol unteers, delegated and helped provide food for refugees staying in hotels, find volunteer doctors, fill out children’s school admissions forms and take refugees to the Department of Homeland Security office for their paperwork. Gradually, resettle ment and other nonprofit organizations recognized their work, and donors started donating generously.

As CH’s influence grew, Hasan regis tered it as a nonprofit organization. Today, Community Helpers USA is a volun teer-based organization, which means that all of its board members, certified public accountants, lawyers and team volunteers have been working for free since 2017. Most volunteers are professionals who work after hours, during work or whenever they have free time.

Founder and current president Hasan is supported by Faisal Imam (treasurer), Nida Imam (head of logistics and Pakistan Projects) and Safiya Aidross (board member and website manager). Together, they have created a Michigan-based organization that runs both domestic and international successful, ongoing projects. Its goal is to

create stable communities with self-sus taining confident, hopeful and empowered individuals.

CH’s involvement in refugee-related activities was the beginning of its U.S.-based projects. Since then, its members have cre ated food pantries in Ypsilanti for refugees and anybody in need. When Afghan refu gees began arriving in Michigan after the U.S. withdrawal, the Community Helpers Youth Group organized clothing drives in Washtenaw International High School and Greenhills Academy. All the items went directly to refugees temporarily residing in a hotel. Not only did they help distrib ute winter clothes, but during the Covid-19 pandemic they organized the distribution of hard-to-get N95 masks to those who needed them most, as well as fresh meals to frontline workers in hospitals.

Over the years, CH has organized international projects based primarily in Pakistan, India and Yemen and completed

projects in Syria and Bangladesh. Pakistani born-and-raised Hasan aims to give back to her birth country.

CH collaborates with other nonprofits to send food, clothes, Eid gifts, tents and other needed items. One of their significant projects is providing water wells and water tanks to Pakistan and Yemen. Hasan’s system lets donors request that customized name plates for themselves or their loved ones be attached on these wells.

CH has established computer labs in Pakistan to introduce IT into underserved areas so their youth can have a chance to learn essential skills, supported orphanages in Syria by providing winter clothes and fire wood, as well as distributing groceries in Bangladesh. In addition, its members have

distributed food in many countries, espe cially groceries, iftar and Eid clothes around Ramadan and Eid.

Hasan, who finds these projects extremely rewarding, looks forward to continuing them in the future. CH also has many ideas for future projects, such as:

➤ Creating a membership system for providing affordable funeral services, a common concern for many low-income Muslim families. This project can give them peace of mind and decrease their stress level.

➤ Setting up a career advising service. This service would be focused on IT and targeted toward youth and stay-at-home parents who need guidance on choosing a career.

➤ Developing a Muslim senior’s home.

Such homes are still rare in Muslim cultures, despite the fact that some of the elderly people don’t have the necessary support or resources.

What makes CH unique is its members’ willingness to sit down with anyone, discuss their ideas and turn their vision into a reality by launching their project and giving them a leading role. Everyone desires to help others, so she made it easy for working people to volunteer whenever they want.

CH provides volunteer options: visiting in person or supporting from home via such remote options as teaching English, Quran reading and free counseling over the phone. As the nonprofit welcomes ideas with open arms, it’s very easy to become a part of it.

Hasan noted that it’s difficult to trust larger organizations, for donors aren’t exactly sure what their money is going. The personal relationship CH fosters with its donors allows its members to build trust and maintain integrity.

Hasan is inspired by the leadership of Abdul Sattar Edhi (d.2016), the Pakistani humanitarian, philanthropist and ascetic who founded the Edhi Foundation. This nonprofit social welfare organization runs the world’s largest volunteer ambulance network, along with homeless/animal shel ters, orphanages and rehabilitation centers. Inspired by the honorable personality of this very humble, driven and knowledge able person, Hasan uses her charisma and personality to motivate the other board members and volunteers to continue their work throughout the years.

Hasan is driven by the fact that with out CH, many families wouldn’t have been given the tools they need to build their new lives. The lack of appropriate governmen tal support was alarming, and she knows that resettlement organizations haven’t changed much since 2016. Another major motivation for Hasan, along with her board members and volunteers, is gaining good deeds and pleasing God. Having an Islamicbased organization has helped her grow into being a better Muslima, and her work feels more rewarding when it is being done in God’s name.

CH started out as just a WhatsApp group among friends who saw a need and responded to it. All it takes to start the butter fly effect to impactful work is one motivated individual with the right intentions. ih

Sima Husain is a freelance writer.OVER THE YEARS, CH HAS ORGANIZED INTERNATIONAL PROJECTS BASED PRIMARILY IN PAKISTAN, INDIA AND YEMEN AND COMPLETED PROJECTS IN SYRIA AND BANGLADESH. PAKISTANI BORN-AND-RAISED HASAN AIMS TO GIVE BACK TO HER BIRTH COUNTRY.

The 27th UN Climate Change Conference, more commonly referred to as COP27 (Conference of the Parties), will be held from Nov. 6-18, 2022, in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt.

This year marks 30 years since the 1992 adoption of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and seven years after the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement at COP21. With the slogan “Together for implementation,” COP27 is billed as an “African COP” both for its location as well

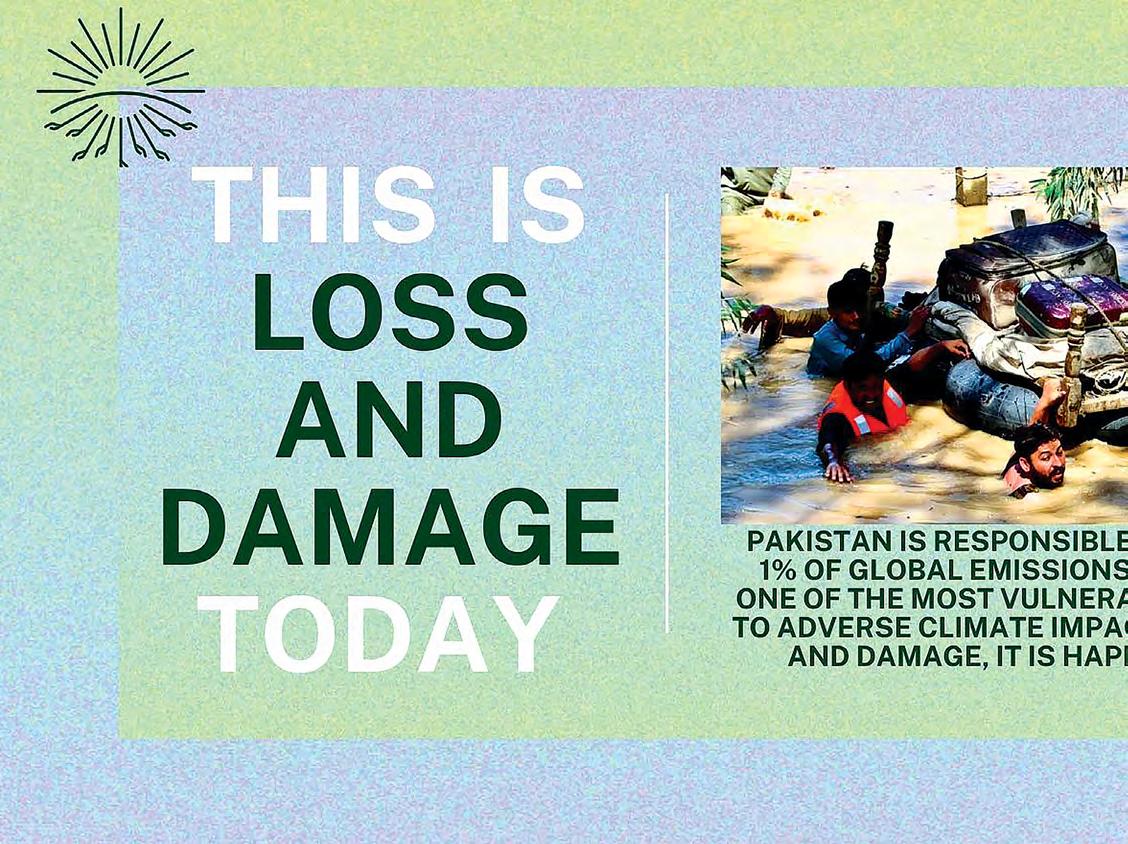

as the expectation that Africa’s exposure to some of climate change’s severest impacts will be front and center. As COP27 is taking place on African soil, amidst worsening impacts and unacceptable suffering, it will be a make-or-break event depending on how it responds to addressing loss and damage (L&D).

Under the Paris Climate Agreement, coun tries recognized the importance of “averting, minimizing and addressing loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate

change, including extreme weather events and slow onset events.” L&D can be averted and minimized by curbing greenhouse gas emissions (mitigation) and taking preemp tive action to protect communities from the consequences of climate change (adaptation).

Addressing L&D is the crucial third pillar of climate action: helping people after they have experienced climate-related impacts. These two issues, a long-running source of tension within UNFCCC negotiations, still have no agreed-upon definition.

At just over 1°C temperature increase, climate impacts are already causing signifi cant L&D worldwide. The poorest countries, however, are being hit first and the hardest. Without sufficient action and support, more than a generation’s worth of human rights and development progress will be wiped out by climate-worsening impacts. As the largest historical emitter, the U.S. has a responsibil ity to respond to take action not just out of a

charitable impulse, but in recognition of the harm done by decades of ongoing emissions.

L&D occur when, due to either slow-onset or sudden events related to climate change, something is irreversibly lost and cannot be repaired or replaced (loss) or something has been broken and requires a financial invest ment to be repaired (damage). These include both financial and nonfinancial losses.

Examples include, but are not limited

• Establish a robust financing L&D system within and beyond the UNFCCC.

• Adequate inclusion of L&D as part of the global stocktake, which occurs every five years, starting in 2023, and is intended to review progress toward the Paris Climate Agreement’s goals.

One reason why L&D has been so con tentious is the developed countries’ concern that compensation caused by adverse climate impacts may be construed as an admission of legal liability and thereby trigger major litigation and compensation claims. As such, these countries fought to include language in the agreement to prevent them from being legally obliged to provide compensation.

However, finance for L&D should not be held back by such a debate. Developed coun tries should provide these funds not because of legal liability, but because supporting vul nerable countries facing unavoidable and existential threats from climate change is the right thing to do.

to, loss of life, income (e.g., destruction of crops by a cyclone or drought, land (e.g., rising sea levels or desertification) and culture (e.g., widespread climate displace ment of communities) • homes damaged by hurricanes or fires and roads damaged by repeated flooding › loss of livelihood (e.g., fish species dying off due to ocean warming) › displacement and loss of homes (e.g., land erosion or mudslides related to sea level rise and/or severe storms) › indigenous com munities’ loss of sacred land due to climate change › and loss of farmland due to climate change, especially for sustenance farmers.

Actions to mitigate these losses and dam ages with direct support must be provided to individuals and marginalized communities, not just to larger international institutions and governments.

We join climate justice voices with the following demands:

• Make L&D a permanent agenda item for future meetings of the COP and subsidiary bodies for every major UNFCCC meeting. These are held each year in May/June and November/December.

• A COP decision to operationalize the Santiago Network on L&D. This network’s vision is to catalyze the technical assistance of relevant organizations, bodies, networks and experts to implement the relevant approaches for averting, minimizing and addressing L&D at all levels in particularly vulnerable developing countries (Decision 2/CMA.2, para 43).

The ISNA Green Initiative Team would like Muslims in general and Muslim Americans in particular to raise their voices for compensation to individuals, commu nities and countries who suffer due to the excessive carbon emissions from the U.S. and other countries. ih

New York City council member Shahana Hanif, who represents Brooklyn’s 39th ward, remembers that grow ing up in the city after 9/11 was not easy. She became very protective of her Kensington community at the tender age of 10, for even then date she could recognize how Islamophobia was harming her fellow New Yorkers and making them feel unwelcome.

Hanif, the first Muslima elected to the council and the first woman to represent her district, recalls how she responded by bringing together neigh borhood youth in her age group to write a letter to then-President George W. Bush calling on him to end anti-Mus lim racism.

She remarks, “We never heard from him, but continued to deepen our com mitment to safety in our community.”