8 minute read

Fake Hafez: How a Supreme Persian Poet of Love was Erased

Fake Hafez: How a Supreme Persian Poet of Love was Erased That so many of the poems attributed to Hafez are fake reveals a Western appropriation of Muslim spirituality

BY OMID SAFI

Advertisement

During summer months I regularly receive daily requests to track down the original, authentic versions of some famed Muslim poet, usually Hafez or Rumi, for Muslims who are getting married and for parents whose children are graduating.

It’s heartbreaking to write that about 99.9% of the quotes and poems attributed to Hafez, one the most popular and influential of all the Persian poets and Muslim sages ever, a member of the pantheon of “universal” spirituality on the Internet, are fake.

Consider these quotes: “Even after all this time, / the sun never says to the earth, / ‘you owe me.’ / Look what happens with a love like that! / It lights up the whole sky.” And“Your heart and my heart / Are very very old friends.” And “Fear is the cheapest room in the house. / I would like to see you living in better conditions.”

Beautiful, but they are not from the real Hafez. They are the pure inventions of Daniel Ladinsky, an American poet who has been publishing books under the name of Hafez for over 20 years.

This hurts, because I know so many love these “Hafez” translations. They are beautiful poetry in English and do contain some profound wisdom. And yet Ladinsky has admitted that they are neither “translations” nor “accurate” and even denied having any knowledge of Persian in his 1996 best-selling “I Heard God Laughing.” His other bestseller is “The Subject Tonight Is Love.”

Persian speakers take poetry seriously. For many, it’s their singular contribution to world civilization: What the Greeks are to philosophy, Persians are to poetry. And in the great pantheon of Persian poetry, perhaps no one’s mastery of Persian is as refined as that of Hafez.

In my introduction to a recent book on Hafez, I said that Rumi (whose poetic output is in the tens of thousands) comes at you like an ocean, pulling you in until you surrender to his mystical wave and are washed back to the ocean. Hafez, on the other hand, is like a luminous diamond, with each facet

being a perfect cut. You cannot add or take away a word from his ghazals. So, pray tell, how can someone who doesn’t know Persian translate it?

In Ladinsky’s own words, “About six months into this work I had an astounding dream in which I saw Hafiz as an Infinite Fountaining Sun (I saw him as God), who sang hundreds of lines of his poetry to me in English, asking me to give that message to ‘my artists and

seekers.’”

While I can’t argue with people and their dreams, this is certainly not how translation works. Christopher Shackle, a great scholar of Persian and Urdu literature, describes Ladinsky’s output as “not so

much a paraphrase as a parody of the wondrously wrought style of the greatest master of Persian art-poetry.” The poet, translator and essayist Murat Nemet-Nejat says it is no more than Ladinsky’s original poems masquerading as a “translation.”

To give credit where credit is due, the following line shows that he is indeed a gifted poet: “I wish I could show you / when you are lonely or in darkness / the astonishing light of your own being.”

That is good stuff. Powerful. Many mystics, including the 20th-century Sufi master Pir Vilayat, would cast his powerful glance at his students, stating that he would long for them to be able to see themselves and their own worth as he sees them. So yes, Ladinsky’s poetry is mystical. And it is great poetry. So good that it is listed on Good Reads as the wisdom of “Hafez of Shiraz.” The problem is, Hafez of Shiraz said nothing like that.

Oprah, the BBC and others have passed on these “translations.” Government officials h ave used them on occasions to include Persian speakers

and Iranians. It is now part of the spiritual wisdom of the East shared in Western circles. This is great for Ladinsky, but we are missing the chance to hear from the actual, real Hafez. And that is a shame.

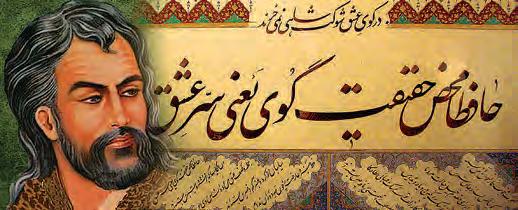

SO, WHO WAS THE REAL HAFEZ (1315-1390)?

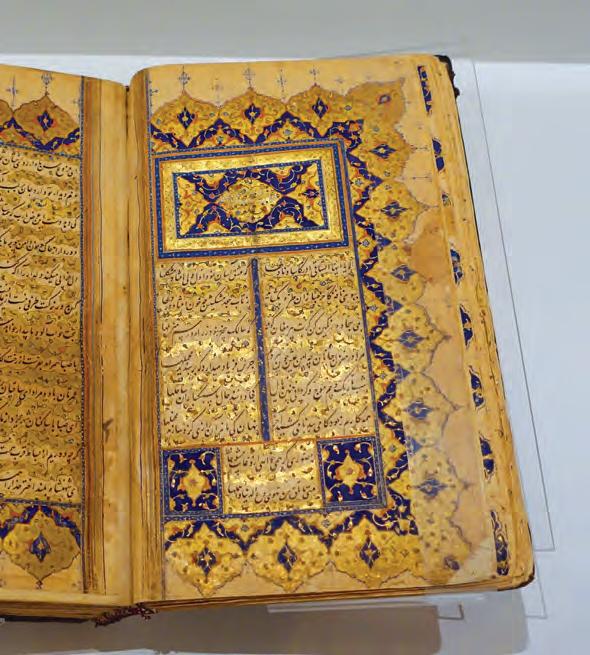

He was a Muslim, Persianspeaking sage whose collection of love poetry rivals only that of Mawlana Rumi in terms of its popularity and influence. Hafez’s given name was Muhammad, and he was called Shams al-Din (The Sun of Religion). “Hafez” is actually an honorific signifying that he had memorized the Quran. His poetry collection, the “Divan,” was referred to as “Lisan al-Ghayb” (“The Tongue of the Unseen Realms”).

A great scholar of Islam, the late Shahab Ahmed, referred to Hafez’s Divan as “the most widely-copied, widely-circulated, widely-read, widely-memorized, widely-recited, widely-invoked, and widely-proverbialized book of poetry in Islamic history.” Even accounting for a slight debate that gives some indication of his immense following, Hafez’s poetry is considered the very epitome of Persian in the ghazal tradition.

Even though his worldview is inseparable from the world of medieval Islam, the genre of Persian love poetry and more, Hafez is deliciously impossible to pin down: A mystic who pokes fun at ostentatious mystics; “he who has committed the Qur’an to heart,” yet loathes religious hypocrisy; one who shows his own piety, yet fills his poetry with literal or symbolic references to intoxication and wine.

The most sublime part of Hafez’s poetry is its ambiguity. It’s like a Rorschach psychological test in poetry. Mystics, wine-drinkers and anti-religious types all see it as a sign of their own yearning. Trying to impose a definitive meaning on him would rob him of what makes him ... Hafez.

His tomb in Shiraz, a magnificent Iranian city, is a popular pilgrimage site and the honeymoon destination for many Iranian newlyweds. His poetry, alongside that of Rumi and Sa‘di, are main staples of vocalists in Iran to this day, including beautiful covers by leading maestros like Shahram Nazeri and Mohammadreza Shajarian.

Like many other Persian poets and mystics, Hafez’s influence can be felt wherever Persianate culture was a presence, including South and Central Asia, Afghanistan and the Ottoman realm. Persian was the literary language par excellence from Bengal to Bosnia for almost a millennium, a reality buried under more recent nationalistic and linguistic barrages.

Part of what is going on here is what we also see, to a lesser extent, with Rumi: the voice and genius of Shiraz’s Persianspeaking, Muslim, mystical, sensual sage, and the communities who have taken Hafez’s poetry to heart for centuries, are being usurped and erased by a White American having no connection to Hafez’s Islam or the Persian tradition. In short, what we have here is spiritual colonialism.

In a 2013 interview Ladinsky asked: “Is it Hafez or Danny? I don’t know. Does it really matter?” I think it matters a great deal, for there are larger issues of language, community and power involved here.

This is not simply a matter of a translation dispute or alternate models of translations, but a matter of power, privilege and erasure. All bookstores have limited shelf space. Will we see the real Rumi or Hafez or not? Did no publisher hire someone qualified to check these “translations” against the original to see if there is a relationship? Was a person with a meaningful connection to the communities who have lived through Hafez for centuries present when these decisions were made?

Even today Hafez’s poetry remains the lifeline of the poetic and religious imagination of tens of millions of human beings. He has something to say — and to sing — to humanity at large. Bypassing those who have kept him in their heart, just as Hafez kept the Quran in his heart, is tantamount to erasure and appropriation.

Our current president ran on a campaign of “Islam hates us” and enacted a cruel Muslim ban immediately upon taking office. As Edward Said and other theorists have reminded us, culture is inseparable from politics. Thus there is something sinister about denying Muslims entrance while stealing and appropriating their crown jewels simply as decor for poetry that is entirely unrelated to the original. Without equating the two, this is reminiscent of White America’s endless fascination with Black culture and music while continuing to perpetuate systems and institutions that leave Black folk unable to breathe.

There is one last element: Ladinsky’s removing Islam from Rumi and Hafez is an act of violence. It is quite another thing to remove Rumi and Hafez from Islam. That is both a separate matter and a mandate for Muslims to reimagine a faith steeped in the world of poetry, nuance, mercy, love, spirit and beauty. Far from merely being content with criticizing such appropriations and erasures, it’s up to us to reimagine the Islam in which figures like Rumi and Hafez are central voices. This has been part of what many of us feel called to and are pursuing through initiatives like I lluminated Courses (https:// www.illuminatedcourses.com). We would love to invite the readers to join us in these courses to see a voice of Islam that is rooted in the qualities of love and mercy, beauty and poetry that made Rumi and Hafez sages and poets worthy of being remembered for centuries. ih

Omid Safi, a professor of Islamic Studies at Duke University, is the founder of Illuminated Courses.