5 minute read

steel yourself

from 1234

A journey inside the legendary Reynolds frame

s the samurai sword glides cleanly through your neck, it’s unlikely that your last thoughts will be of the meticulous folding and layering of steel that went into the blade’s manufacture. With any luck, the tangled whirl of your brief existence will flicker through your fading consciousness as carotid claret sprays luridly all around. But sword aficionados – especially those whose lives depended on their blades – had a keen interest in steel and its structural qualities. The men who made those blades became legends. A

As you glide cleanly through the rush hour traffic, it’s similarly unlikely that your mind will dwell upon the processes that resulted in your bike’s frame behaving as it does. But bike aficionados give a great deal of thought (and money) when choosing a frame material. The varying qualities of different metals – stiff, superlight carbon, imperious titanium, lively steel – all give a different ‘feel’ to the ride, and bring their own distinct characteristics.

And of the men and women who make these frames, many are now legends. When it comes to steel, one name stands out: Reynolds.

But it is not frames themselves for which Reynolds are most famous, but the simple steel tubing needed to construct them. Their slender, elegant tubes have carried the winners of 27 Tours de France and made the company a household name around the world.

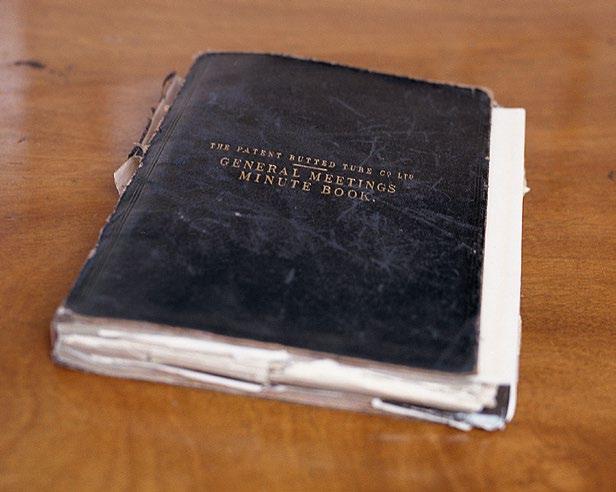

It all began with nails. John Reynolds – the man who started it all – was born the same year as the Battle of Waterloo (that’s 1815, fact fans). At 26, in 1841, he founded a company producing ‘cut’ nails – nails stamped out from rolled iron. The company became very skilled at powered metalworking processes. Years passed, the business thrived, and when the bicycle boom of the 1890s began exciting industrialists across Britain, John’s grandson Alfred turned his mind to the possibilities of manufacturing seamless steel cycle tubing, and, more importantly, to overcoming a problem which was troubling the bicycle builders of the time – how to overcome the weaknesses caused by joining thin tubes to relatively heavy lugs. Before long, Alfred had cracked it, devising a means of manufacturing tubes whose wall thickness increased at the ends only, without increasing the outside diameter, giving the cycle builder the much needed extra strength at the joints and eliminating the necessity of inserting a liner into each end of a tube, which, until then, had been the only means of achieving this.

n 1898, the Reynolds Tube Company was officially founded and it has remained at the forefront of bicycle production ever since – barring a few years during the two world wars, when work for the war effort took over. This led into tubing for aviation, and the ongoing quest for lighter, stronger tubes – a quest which bore fruit in 1935 in the form of the now world-famous Reynolds 531. The ‘5,3,1’ figures are the ratio of the three main elements in the steel’s chemical composition. Now you know. I

Reynolds as a business has diversified and grown into many areas of engineering, embracing new materials including titanium, aluminium and carbon fibre. They’ve been called upon on to make all sorts of things, from Spitfire wing struts to flamethrower parts and even the oxygen tanks used by Edmund Hillary when he conquered Everest. One of these original tanks ended up being used as a gong, calling the Lamas to prayer at the monastery of Thyangvoche at Khumvu, high in the Himalayas. What a strange journey Reynolds steel has made from those first cut nails of 1841.

The bicycle tubing’s a tiny part of what Reynolds do now, but to cyclists there will always be something reassuring about those familiar green and gold labels bearing the legend ‘531’, ‘753’ or, if you’re very lucky, ‘953’.

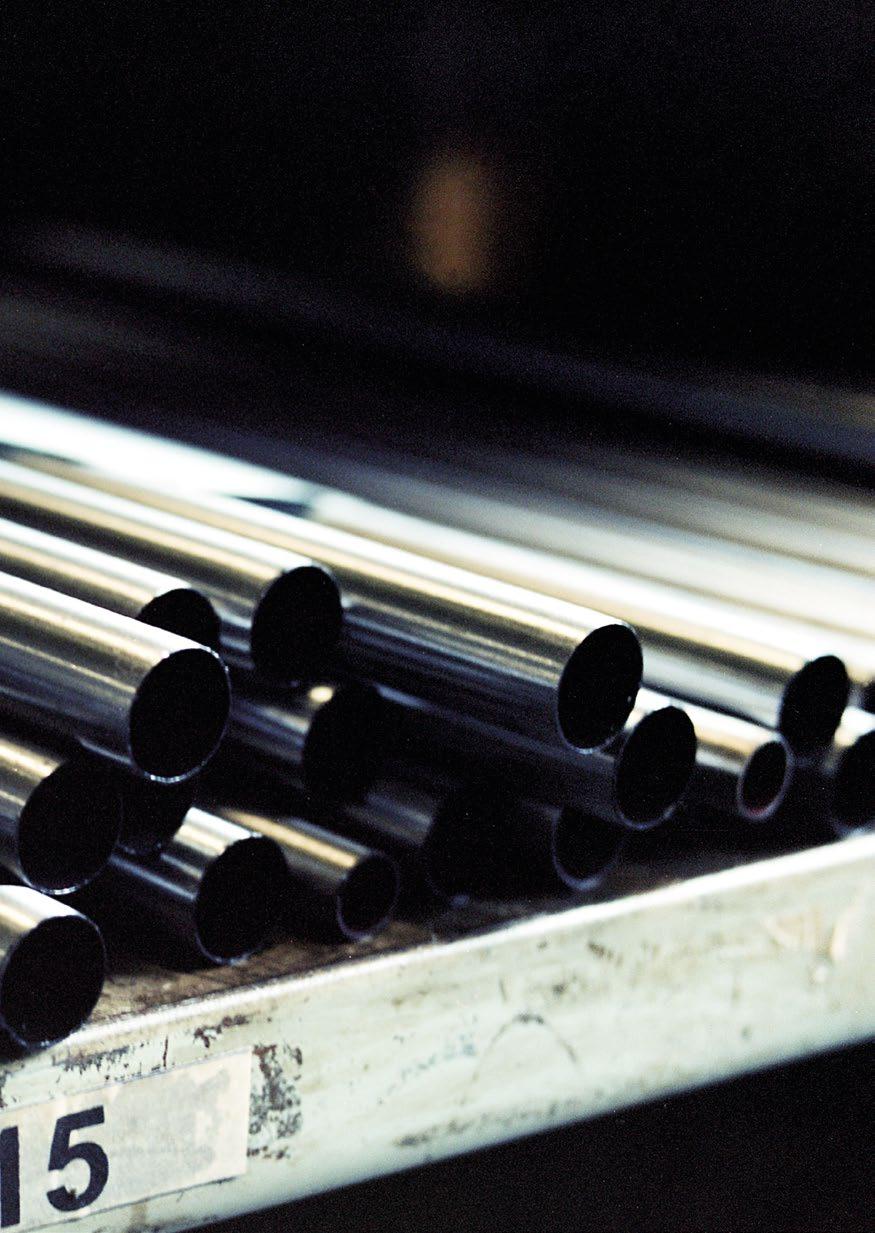

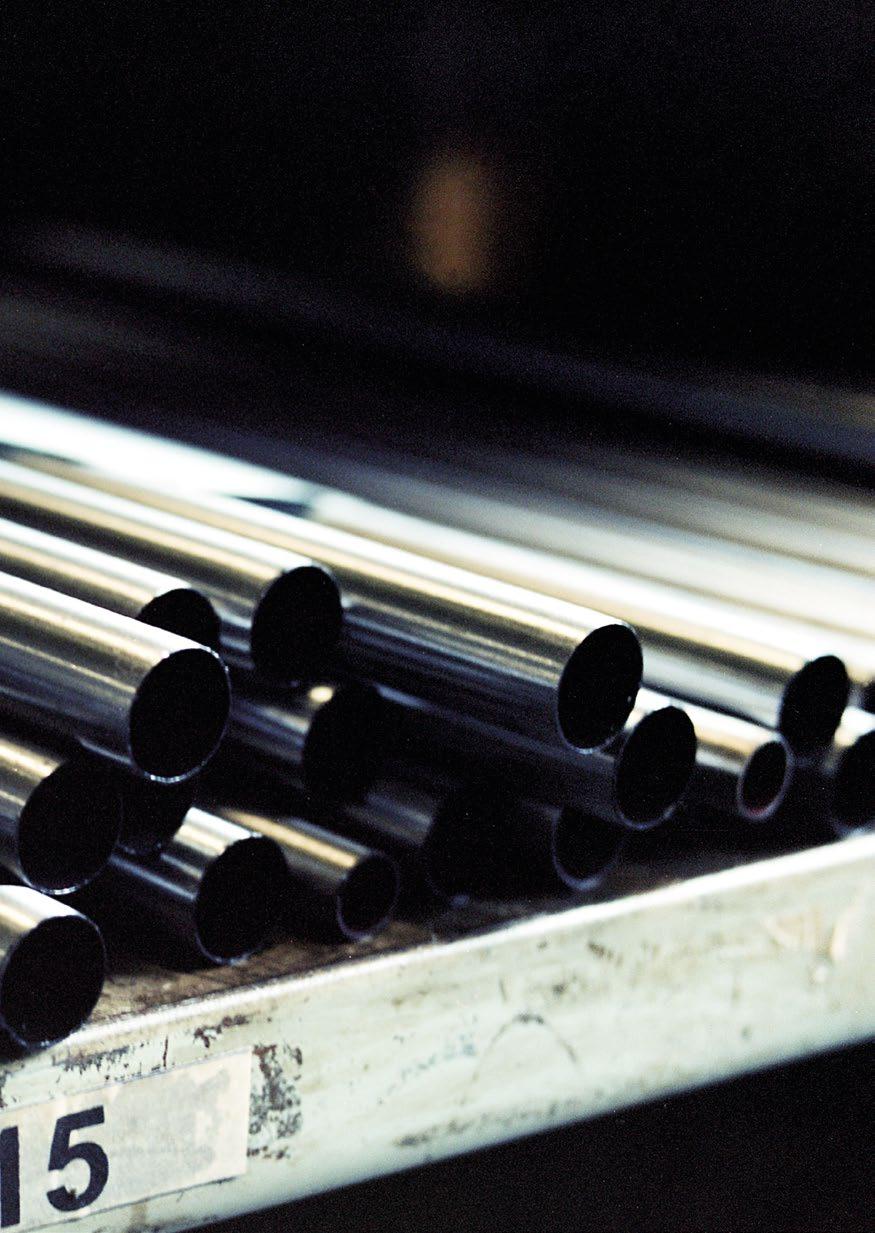

When photographer Chris Lanaway went to visit the hallowed Reynolds production plant in Birmingham, he was struck by the “industrial aroma”, the orderly arrangement of machines and men, the prevailing sense of calm efficiency. Through a door painted in Reynolds’ signature livery, two old prototype frames by British bicycle builders hang proudly above the vast machine that draws each tube to a specified diameter.

Tucked away in the corner lies what Chris describes as “some form of torture chamber”, a large machine “encased in a steel container which when fired up unleashes repeated banging that resembles a mid-summer thunder storm rumbling through the factory floor”. This machine produces fork blades and oval-shaped tubes by a cold forging process which forces the metal into shape.

Once finished, each tube set is meticulously inspected and carefully boxed up; a selection of boxes sit neatly beside the inspection area labelled with the names of individual frame builders awaiting their delivery.

It may be 20 years since steel left the pro peloton, but it continues to fuel the growing cottage industry that is bespoke frame building. The number of independent frame builders has seen a happy resurgence in recent years, as more cyclists opt for characterful, custommade steel over mass-produced aluminium and carbon frame sets. Earlier this year the Madison-Genesis cycling team announced that their riders would be competing on 953-built bikes, saying “in 953, Reynolds have a steel tubeset to trump Titanium, clawing back some much needed, long-lost ground to the favoured modern materials – stainless, stiff, competitively light yet still retaining that unmistakable compliant and roadconnected ride feel for which steel is famous.”

More than a century after the release of the first double butted tube, steel remains the stuff of legend.