12 minute read

The Glorious Glass Art of Gloria Badiner

from Encore July 2020

Brian Powers

She gave up cell biology for a career as an artist

Advertisement

by LISA MACKINDER

When Gloria Badiner laid eyes on cast glass for the first time, 25 years ago, it was love at first sight — but her newfound love had consequences.

“Our house kind of filled up with glass,” says the artist and owner of Arts & Artifacts Glass Studio in Mattawan.

Badiner, then a cell biologist for the former Upjohn Co. (now Pfizer Inc.), was working on a paper at Brown University when she wandered into the Rhode Island School of Design and discovered an exhibit of cast-glass art, which is created by pouring molten glass into a mold.

Back in Kalamazoo, she enrolled in a class at the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts on glass sand casting. During that class, she found a 1950s-era kiln in the dumpster, promptly rewired it, set it up on a card table in her kitchen and got busy, and that’s how her home became overrun by her own glass creations.

“And my husband (David Badiner) goes, ‘Have you ever thought of selling any of it?’” Badiner recalls. “And I go, ‘Who’d buy it?’ It never occurred to me. I was just playing.” Badiner called up Jerry Catania, a professional glass blower she had met during the sand casting class who, with his wife, Kathy, owned Vesuvius Art Gallery, in Glenn.

“They said, ‘Sure, bring some stuff by,’ and I really haven’t looked back.”

Within a couple months of placing her work at Vesuvius, Badiner had her pieces displayed in another gallery and had been asked to teach a class at Ox-Bow School of Art and Artists' Residency, in Saugatuck. But her fast-paced success as an artist didn’t immediately sink in. A pivotal moment occurred when the Badiners were shopping in a bookstore and Gloria was selecting books such as Business for the Crafter.

“My husband took the stacks of books I had and put them on a table and goes, ‘You’re already there, honey,’” Badiner says.

She faced a decision: Art or science? Badiner loves science, which she refers to as “the never-ending story.” But cast glass, as Badiner jokes, “ate away at her brain.” When light enters a piece of cast glass, she says, it gets trapped inside because the surface isn’t smooth. She loves how the light bounces around inside.

“It was the translucency of the glass,” she explains. “I just want(ed) to know everything about this.”

Badiner knew that she couldn’t successfully do both careers. To be a good scientist, she says, takes constant study, so she decided to launch a career as an artist. From kitchen to studio

Before long the workspace in her farmhouse kitchen didn’t cut it anymore. She moved into an unheated barn on their 80- acre property in Mattawan, but that didn’t last long either. The barn roof leaked.

“One day I actually got a shock off the kiln because the water had come down,” Badiner says.

So the Badiners tore down an old carriage house on the property and built a new garage. She used the upper floor as a studio, and they built another outbuilding for the kilns. That arrangement was temporary as well.

Last September, Badiner moved into a new, dedicated studio building constructed on their property. It’s a roomy space with high ceilings, colorful glass panels on one wall, eye-popping finished pieces on other walls, and work tables in the middle. There’s even a kiln room, which houses ovens, tools and five kilns, including the 4-foot-by-6-foot kiln Badiner lovingly refers to as “Big Blue.”

Brian Powers

This page, top: Badiner and her “Big Blue” kiln she uses to create many of her works of art. Bottom: Prairie Life: Spring Storms, Planted, First Frost, tryptic, frit, fused glass on kiln-formed tablets, barnwood. At right, top: Badiner, surrounded by glass in her Mattawan studio. Bottom: Waterfall, kiln cast glass, patinated copper and stainless steel (commissioned work).

“She’s on wheels,” Badiner says of Big Blue, speaking about “her” with the same affection car aficionados have for their vehicles. “I can even put her out in the studio, do all my layout here and then just roll her back in.”

Badiner’s fondness for Big Blue is understandable.

“I invested in this kiln when I had a big commission for the Ronald McDonald House in Chicago,” Badiner explains. Making art that matters

In 2011, a representative of Ed Hoy’s International — the largest art glass distributor in North America — contacted Badiner with a question: Would she be interested in working on a project that honored Hoy? Hoy, a pioneer in the development of products and equipment for the cast glass industry, was turning 90. Badiner jumped at the chance. She’d known Hoy for many years and taught classes for his company.

“I have to tell you (about) the first time I ever met Ed,” Badiner says, chuckling and leaning in to tell the story.

In 1995, Badiner visited Ed Hoy International in Warrenville, Illinois, and before she’d been introduced to Hoy he came “barreling” out of his warehouse, holding up a tool in his hand.

“This is the coolest thing ever!” Badiner remembers Hoy exclaiming to her. She admits, “I didn’t even know what it was used for.”

The tool was a handheld electronic pyrometer — a remote sensing thermometer used to measure the temperature of a surface — which Hoy helped invent. Before that, pyrometers were stationary and installed on a wall. Hoy’s enthusiasm made an impression.

“I thought if I could be 75 and still be like that, I have picked a great career,” says Badiner, now 65.

In addition to honoring Hoy, Badiner was compelled to do the commissioned piece

because of where it would be displayed: in the lobby of the new 90-apartment Ronald McDonald House in Chicago. She wants her art to matter, so it meant a great deal to her, she says, “to have something like that and do something working with a group that works with ill children and their families and takes such good care of them.”

For the installation, Badiner created a serene lakeshore scene with reeds, grasses and purple flowers. It’s composed of five glass panels 2.5 feet by 3 feet that weigh 100 pounds each.

Such natural themes are typical of Badiner’s work, which now includes fused, kiln-cast, sand-cast and dalle de verre works (pieces of colored glass set into concrete and epoxy resin or other supporting material). She and her husband used to climb mountains, but now, both in their 60s, settle for bouldering, which involves climbing on small rock formations or artificial rock walls without ropes or harnesses. The couple recently returned from Big Bend National Park, in Texas, where they hiked and bouldered in a variety of places, including Chisos Basin.

As usual, this natural getaway inspired Badiner’s art. She says she was fascinated by the change within the basin from limestone to sandstone and the layers in between exposed rocks. She marveled at how stones would flip: limestone on top of sandstone and then vice versa. Observing the layers filled her mind with ideas. “Tonal ideas, use of color, stark changes, lines in between — that all becomes more interesting (when making a piece of art),” Badiner explains. “You could just put two pieces together — not so interesting.”

Looking at the subtleties of what’s happening with the rocks, whether tonal difference or granule size variation, she says, “helps me build ideas and images.”

Badiner’s fascination with rock formations dates back to childhood. She recalls a trip with her parents driving through Pennsylvania in their little black station wagon. As a young child, Badiner stared out the window at the layers inside of exposed rock and became captivated.

“I just had to have one of those rocks,” she says. Her parents pulled over to satisfy her request. Badiner chuckles and adds, “They

Brian Powers

Inspired by rocks

were such good parents!”

She admits she loves holding rocks and feeling their textures. David, who well knows Badiner’s interest in rocks, will tease her to put a rock back where she found it because in the past he has found rocks tucked into his empty shoes. ‘All about corn’

As an artist, Badiner has found creative growth by participating in a number of residencies, including two at Pilchuck Glass School, in Stanwood, Washington, which was founded in 1971 by internationally known glass artist Dale Chihuly.

“You’re invited to come and develop your voice to be stronger, and you’re there with colleagues that are at the same (stage of) professional development — whatever age they are,” Badiner says.

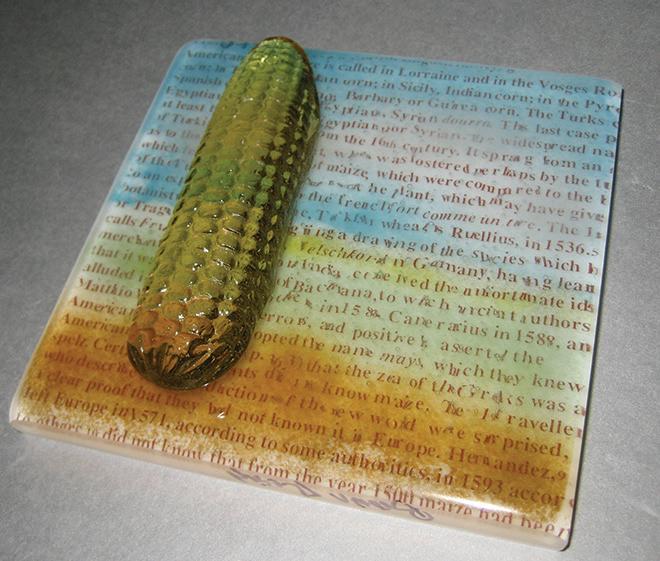

Badiner’s work used to center on fuel and food, but after her Pilchuck residencies her work began to focus on the issue of hunger. Hunger can be a dark subject to approach, she says, but Badiner translates this subject into her art through an overriding theme: corn. “It’s all about corn!” she exclaims, laughing.

The image of corn evolved from her former work on the subject of fuel. Driving through Illinois, Badiner saw big cornfields with signs that read, “This is our new fuel,” and she observed that corn was being taken out of the food chain for ethanol production. As that industry grew, she says, hunger went up.

Badiner also noticed changes in agricultural practices, such as farmers plowing to the edge of a field. Without buffers, that creates runoff and contamination downstream, she says.

“I made a piece that was blown — actually blown in cast glass — and it had corn cobs that were filled with fuel,” she says. “And then I put the husk on top and tied it like grenades, so, you know, this is a time bomb waiting to go off.

“Corn just became the motif. I grew up with corn. I had a field across the street from me when I grew up. Both of my parents are farm kids.”

Brian Powers

Clockwise from top left: Take Your Medicine, kiln cast glass, blown glass, Bakelite and found objects; Badiner in her studio holding Plenty, kiln-formed panel with fused powders and cyanotype on barnwood; Self Rising, cyanotype on cast kiln-formed glass; and It is Written, kiln cast glass, kiln-formed layered stack with painted powders and cyanotype script, a piece from her Thesis on Hunger.

One of Badiner’s other takeaways from her Pilchuck residencies was discovering that her work speaks strongly to others.

“People are really getting what I’m trying to say,” she says, “and that was really important to me right at that time, because I wasn’t just making production work to have a studio. I was trying to make personal work that spoke to people, whether it sold or not.” Teaching others

Glass, rocks, corn, fuel — Badiner is a woman with many passions. Add teaching to that list too. Badiner teaches classes in kiln casting, which involves heating glass above or inside a mold until it flows to fill the void. She taught at Ox-Bow School of Art and Artists' Residency for six years and now teaches classes at her studio, at Paw Paw Brewery and at Meijer Gardens in Grand Rapids, to name a few places. In addition, she has taught children, including students at two elementary schools in Chicago.

“I love to watch people use the material, in particular children. They’re fearless,” Badiner

Is Your Doctor Moving to Bronson?

Starting July 1, 2020, this group of experienced primary care providers will begin seeing adult and pediatric patients at these new Bronson locations. Choose a location and provider and get connected to exceptional care and all the resources the region’s leading healthcare system has to offer.

Appointments for July, 2020 or later can be scheduled online now at bronsonhealth.com/PrimaryCarePartners or call (269) 341-7788.

Bronson Primary Care Partner Locations:

9th St. • 5973 Beatrice, Kalamazoo East Centre • 2700 E. Centre., Portage Galesburg • 10310 Miller Dr., Galesburg Richland • 8906 M-89, Richland Texas Corners • 8088 Vineyard Pkwy., Texas Corners Three Rivers • 601 S. 131, Three Rivers West Main • 6210 W. Main St., Kalamazoo

bronsonhealth.com/PrimaryCarePartners

Summertime Live

SPONSORED BY

local venues & totally free!

The Michigan nightingales!

Sunday, July 19 at 4 pm

Bronson Park, 200 S. Rose Street

Come join us for some socially distanced, safety-first fun as we kick off Concerts in the Park in Bronson Park!

For Full Summer Schedule, visit: KalamazooArts.org

Fence, gate and railing services since 1981

says. “They just go right at it. They’re not caution-directed like adults.”

Badiner has also taught continuingeducation classes for Illinois art teachers, demonstrating how to use copper wire and inexpensive or donated plate glass to make art. Most of the art teachers already have a kiln, she says.

“It’s just a matter of sharing the technology of how to use their own resources to bring glass art into the classroom and to do it on a low budget,” she says. Still playing with science

Admittedly, Badiner never completely hung up her lab coat — cast glass keeps "my science brain engaged quite a bit,” she says. She continues to experiment with applying different techniques to her glass work. For example, she recently began using a cyanotype photographic technique used in the 1860s. During this process, a photograph is developed in sunlight under running water, gets placed on top of glass and then put into a kiln. When taken out of the kiln, the image has been transferred to the glass.

“They only make paper for glass or ceramics in a standard sheet (for cyanotype), and I work bigger than that,” Badiner says, “so I had to develop a technique that I can use on glass.”

Badiner created her own handmade emulsion and paints this emulsion onto the glass, places the photograph on top and puts it into the kiln. After removing it from the kiln, she wipes away the emulsion. The image has transferred to the glass.

Explaining the science of the process, Badiner says, “Where you make your exposure, there’s an iron precipitate chemical reaction with the heat, and it precipitates the iron, and then that actually sticks to the surface of the glass and it’s permanent.”

Perhaps it is this never-ending story of creative growth that makes Badiner love her second career so much that she says she never sees an end in sight.

“I don’t want to retire,” she says. “I want to keep doing this.”