12 minute read

2022 CVM Homecoming Awards True & Valiant

Howard Hill

Lorraine J. Hoffman Graduate Alumni Award

Advertisement

Dr. Howard Hill may have grown up in Southern California. His DVM degree may be from the University of California-Davis.

For the past five decades however, Hill has been an Iowan.

“My roots are more Midwestern now,” Hill said. “I have a strong love of the land and livestock here in Iowa.”

Hill’s Iowa connection began shortly after graduating from vet school. He was practicing at a mixed animal clinic in California but was looking for something else. When he noticed a National Institute of Health Fellowship opportunity, he reached out to two schools.

Iowa State’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Dr. R. Allen Packer responded, and the next thing Hill knew he was working on a master’s degree in microbiology. He completed that degree in 1973 and his PhD the following year.

Four months before he completed his PhD, Dr. Vaughn Seaton, then director of Iowa State’s Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, called and offered him a job.

“I thought we would stay for a couple more years before moving back to California,” Hill said.

Those two years became decades and a series of jobs in Iowa. His first was at the VDL where, while head of the veterinary microbiology section he taught veterinary and graduate students and served the animal production industries, particularly the swine industry in its national fight to eradicate pseudorabies (PRV).

In 2000, Hill joined Iowa Select Farms where he helped the company eradicate its PRV problem. He also worked on the porcine reproductive respiratory syndrome and put in place mechanisms to prepare the swine industry to respond to future challenges. He retired as the company’s chief operating officer in 2013.

Hill’s work with the swine industry wasn’t confined to just swine production companies. He has served on countless committees to combat, eradicate, and prepare for African Swine Fever and other potential foreign animal diseases.

His family raises not only pigs but purebred Angus cattle, while farming 3,000 acres of corn, soybeans and hay.

“My career has revolved around pigs,” he said. “Today our family owns swine finishing farms.”

“By raising pigs I’ve become active in many organizations and have traveled extensively representing the nation’s pork industry’s interests.”

From 2010-16, Hill served on the National Pork Producers Council Board of Directors and was president of that organization for a year. He was one of nine veterinarians appointed to serve on the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Advisory Committee of Veterinary Medicine.

And in 1996, he was the president of the American Association of the Swine Veterinarians.

“I enjoyed working on the policy side of the swine industry,” Hill said, “and informing people how important it is to support livestock and the veterinary profession.” gd

Aubrey Cordray Outstanding Young Alumni Award

After Dr. Aubrey Cordray graduated from the College of Veterinary Medicine in 2014, she wanted to practice mixed animal medicine in a community in which she could invest.

Yet being a veterinary clinic owner was the furthest thing from her mind.

“It was never my goal to own a clinic,” Cordray says, “but you never known what path your career will take.”

Regardless of her goals, owning a clinic is right up her alley and anyone who knows Cordray knows that failure isn’t an option, even in the small town of Humboldt, Iowa, population 4,773.

“If I’m going to do something, I’m going to do it to the best of my ability,” she said.

Cordray has done just that with the Humboldt Veterinary Clinic, a clinic she purchased in 2017 after joining the practice and serving as an associate veterinarian after her graduation. At the time there were just one full-time and one part-time veterinarian on staff.

Today, Humboldt Veterinary Clinic has 23 employees including five clinicians, while expanding from a 3,500-foot-facility to one more than three times that size.

“The facility needed a facelift,” Cordray said. “I saw a need for this big of a facility and things are going well. We were busting at the seams for small animals, and we needed a space for producers to bring their animals to us, instead of our clinicians always going out to the farms.

“It wasn’t cost and time effective for us or the producers to make calls 90 minutes away from the clinic.”

Cordray’s vision expanded her small animal clinic from two rooms to four plus isolation suites and doubled the surgical suites to two. The large animal area is a progressive haul-in facility with customized equipment.

Humboldt Veterinary Clinic isn’t your typical small town or even big city clinic. A fish tank in the lobby, as well as snacks and other refreshments provide a distraction for clients’ children. A merchandise corner was another addition.

“We wanted clients to have a great experience in addition to high level veterinary care,” Cordray said. “There are other projects on the radar as well.”

It’s quite the leap of faith for Cordray to make in small town Humboldt. It helps that she has built a loyal client base which extends as far away as Forest City, Iowa, a good 75 minutes from Humboldt.

“We are a comprehensive veterinary clinic that offers services others may not,” Cordray said. “When you believe in something you can make it happen.”

Not only does Cordray believe in what she can accomplish, but she believes in her team at Humboldt Veterinary Clinic. The culture in the workplace is important to Cordray and she stresses “authenticity, comprehensive, compassion, team, and honesty.”

“She strives to practice medicine and operate a business based on those values each day,” wrote Dr. Tracy Lindquist (’12), one of the five veterinarians at Humboldt Veterinary

Clinic. “She provides a great learning environment for veterinarians, technicians, and assistants.”

One of the things Cordray wanted to do while expanding the clinic, was to provide special spaces for her employees and their families. There is a kid room with a pull-out futon, big screen TV and toys.

Music, picked by the staff, plays overhead as you tour the clinic which also includes a staff break room and a basketball hoop in the large animal area where the former Buena Vista University star can shoot some hoops.

She considers her team as family and works hard to get to know them outside of work. The clinic staff has gone on scavenger hunts, played putt putt golf and kayaked together.

“We have three or four team-building events a year that I believe helps with our cohesiveness,” Cordray said. “We get to know each other outside of work.

“I’m grateful to my team – they never stand behind me but stand before me.” gd

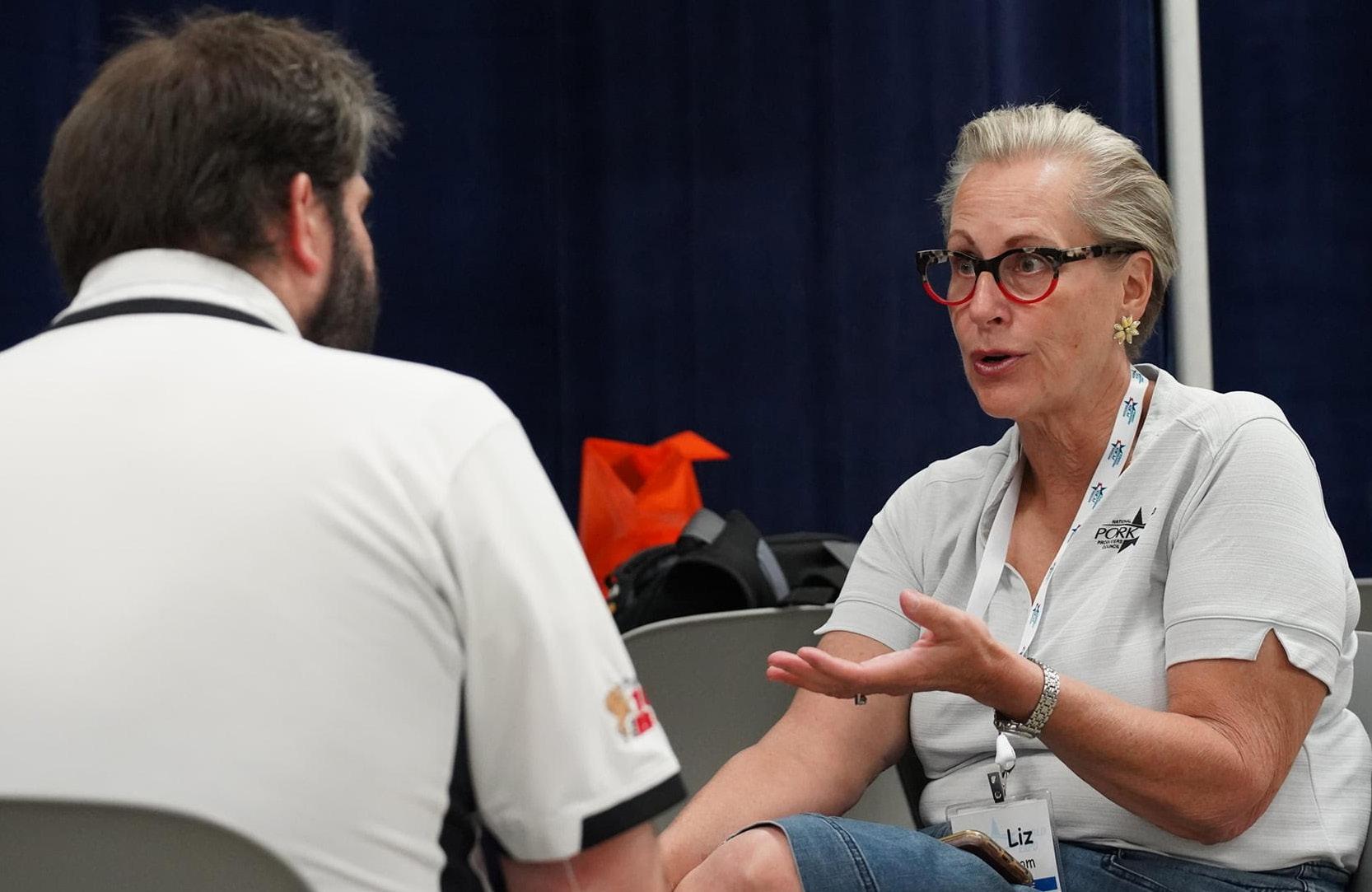

Elizabeth Wagstrom

William P. Switzer Award in Veterinary Medicine

On the day Elizabeth Wagstrom’s son started his freshman year in high school, she was starting her own adventure.

“I drove 175 miles down the road to Ames and said, ‘see you guys next weekend,’” Wagstrom recalled.

Wagstrom’s adventure and laterin-life career change was attending veterinary school at Iowa State. Previously she was working in the swine industry at Oxford Laboratories with a pair of Iowa State graduates –Drs. Wayne Freese and Wendell Davis.

Only she was in sales, not working directly with pigs.

“Working at Oxford Laboratories really gave me a passion for pigs,” Wagstrom said, “and I decided I was on the wrong side of the counter when I went into a veterinary clinic.

“I thought, ‘I’m on the outside and there are veterinarians on the inside.’ I knew I could do that and I wanted to do that.”

On a whim, Wagstrom threw together a vet school application, thinking it would be practice for the following year when she would get serious about her career change. Funny thing though – she was admitted to Iowa State.

And the

rest, as people say, is history.

After graduating from Iowa State with a DVM in 1999 and a master’s in preventive medicine a year later, Wagstrom spent her new career working at the intersection of animal and public health.

“It all fell into place for me,” Wagstrom said, “but it has been a bit of a journey.”

Her new career started out at Iowa Select Farms during a time Wagstrom describes as horrible for the pig industry.

“It was very much a learning experience for me, almost a trial by error,” she said.

Even though she was in the swine industry, Wagstrom knew what she wanted to do. Positions at the Minnesota Department of Health, the National Pork Board and the University of Minnesota contributed to finding her passion at the National Pork Producers Council (NPPC).

“The wonderful thing about the NPPC and the National Pork Board is that they take complex scientific knowledge and distill the information so lay people can understand,” Wagstrom said. “This allowed me to apply my scientific knowledge to public policy and it was a really good fit for me.”

As the NPPC’s chief veterinarian (now retired), Wagstrom advanced domestic and international animal health and welfare, and on-farm production, public health and food safety issues. She was a member of the coalition that secured $150 million in funding for an animal disease vaccine bank, foreign animal disease prevention and preparedness grants, and for the National Animal Health Laboratory Network in the 2018 Farm Bill.

During her career, Wagstrom collaborated with and educated non-agricultural audiences on animal production and the U.S. pork industry’s efforts to protect animal health, welfare, public health, and the environment. She frequently testified before Congressional committees and was the NPCC’s spokesperson.

“I’m just fascinated by the swine industry,” Wagstrom said. “So much of the decision making is based economics and epidemiology and it just fit together so well that it made the swine industry a natural home for me.” gd

Amy Baker Stange Award for Meritorious Service

No way was Amy Baker’s career path going to led to her becoming a veterinarian. No way in the world.

Her father, Dr. Butch Baker, was a veterinarian and had a mixed animal practice. Baker recalls her dad’s message to her.

“He said, ‘do something else where you don’t have to work so hard,’” Amy Baker said. “I resisted the call to do veterinary medicine as a young adult because of the long hours and the physical demands of the job that I saw my dad and his practice partners put in.”

Amy Baker’s calling was something else.

“I was going to be a medical doctor, a psychologist, a swine genetist,” she said. “I could have done those jobs.”

After completing her undergraduate degree at Western Kentucky University Baker started graduate courses at Iowa State, earning a master’s in genetics.

But the pull of the family career was just too much for her.

“When I imagined the possibilities of being a veterinarian doing infectious disease research I knew my career path,” Baker said, “and despite what he had said to me, my dad was pretty excited when I committed to becoming a DVM.”

And what a DVM. Baker is a superstar DVM (2002) as a research veterinary medical officer and lead scientist at the National Animal Disease Center in the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Ames. Among her achievements, she has led a research team in profiling the genetic evolution of swine influenza A viruses and how this affects the animals’ immune response to the pathogens.

She also initiated a global nomenclature system to expedite vaccine selections, strain identification and comparisons, and studies of viral evolution and “mixing,” whereby influenza strains from different hosts species exchange their genes.

But that’s not all. Baker was instrumental in establishing a national influenza A virus surveillance system in collaboration with the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“I exclusively study influenza and it keeps me engaged,” Baker said. “There are lots of variants, it isn’t just one virus.”

Baker describes the diversity of influenza as being “SARS-CoV-2 on steroids.”

“There are more ways influenza viruses can evolve than coronaviruses can do, through host jumps and gene segment swapping” she said. “This is a global issue and I’m as worried about the unknowns as much as I am about the knowns.”

Baker’s work in this area led to her election in 2020 to the National Academy of Medicine, one of the highest honors in the fields of health and medicine. Her numerous awards also include the Arthur S. Flemming Award for her exceptional scientific achievements in the field of animal health.

For that award, Baker was just one of 12 award recipients in 2019 across the entire Federal Government. “I definitely feel humbled when I get nominated for an award and I’m surprised when the selection committee picks me,” Baker said.

“I have had the opportunity to often be the one on the stage being honored, but all of this wouldn’t be possible without the outstanding team of colleagues I work with.

“There is no better place than Ames, Iowa, to do what I do.”

Despite the success Baker has had in her field, she’s not satisfied.

“I’m still on the hunt for better vaccines to use in pigs,” she said. “Influenza is a fascinating virus and it’s not going to get boring.

“I still get excited. I love my job and the influenza research community I work with. It is almost like I knew what I was doing all those years ago when I started on this journey.” gd

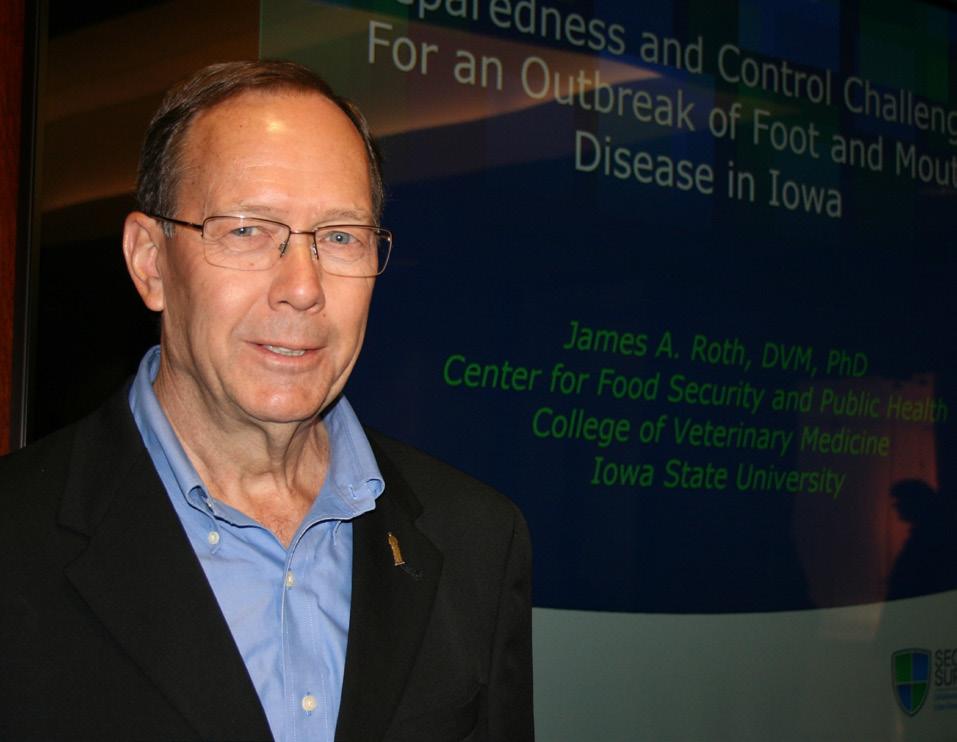

Jim Roth Stange Award for Meritorious Service

In his acceptance speech for the Stange Award, Dr. Jim Roth pointed out he is a member of the Class of 1975 or as he termed it “the famous class of 1975.”

No less than five members of the class of ’75 have been either awarded the Stange Award or the Switzer Award by the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Roth’s selection as a recipient of the Stange Award for Meritorious Service is number six.

But it isn’t just his fellow classmates who have received the college’s highest alumni honor.

“I have a lot of mentors who have received this award,” Roth said. “I have known most of the Stange awardees and that is why I’m so honored to receive this award.”

Roth’s inclusion in this exclusive club is overdue. A three-time graduate of the college (DVM ’75, MS ’79 and a PhD in immunology ’81), Roth holds more titles and has received more awards than the average Iowa State alumnus.

He’s a Clarence Hartley Covault Distinguished Professor in Veterinary Medicine at Iowa State. He holds the Presidential Chair in Veterinary

Microbiology and Preventive Medicine. In 2002, Roth established the Center Food Security and Public Health (CFSPH), of which he continues to serve as the director. And he is the executive director of the Institute for International Cooperation in Animal Biologics (IICAB).

He has devoted his career to Iowa State, spending 45 years on the College of Veterinary Medicine faculty.

“If you want a career in animal health, there is no better place to do that than Iowa State and Ames,” Roth said.

Most of his classmates from the “famous class of 1975” probably stayed on one career path trajectory. That wasn’t in the cards for Roth.

“I’ve had at least three transitions after returning from private practice to join the faculty,” he said. “I started out as a classroom instructor and basic immunology researcher, then gradually began to emphasize infectious disease prevention. Today I devote most of my time to the mission of the CFSPH – to increase national and international preparedness for accidental or intentional introduction of diseases that threaten food production or public health. Science changes so fast, you need to change with it and try to stay ahead of the game. I’ve kept my career fresh by moving into different areas.”

With the development of the Veterinary Biologics Training Program in 1995, Roth and his team have provided an educational program covering the USDA process for approving vaccines and diagnostics.

Working with the USDA Center for Veterinary Biologics in Ames, this annual program has had more than 3,000 participants, including more than 875 international attendees from 96 countries.

He currently focuses on secure food supply projects while also working with state and federal officials and industry in planning for optimal responses to transboundary and emerging diseases that threaten the food supply or public health.

Roth has testified before Congress on biosecurity preparedness, on efforts to address bioterrorism and agroterrorism, and on the need for vaccines for foreign animal diseases.

All of which has led him to be recognized by several different organizations. He is a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and in 2016 was named to the National Academy of Medicine.

Other awards include the Distinguished Veterinary Immunologist Award from the American Association of Veterinary Immunologists, Public Service Award from the American Veterinary Medical Association, the Senator John Melcher Leadership in Public Policy Award from the American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges, and the USDA APHIS Administrator’s Award for lifetime achievements in animal health.

“I have a lot of history here, but everything I’ve accomplished has been a team effort,” Roth said. “If it was just what I’ve accomplished, I wouldn’t be getting these awards. The CFSPH and IICAB staff members are a dedicated and talented group. They do exceptional work and bring honor to me, the College of Veterinary Medicine, and the whole university.”gd