The 2024 edition of A Trade Union Take on the SDGs gives an independent, workers’ perspective on how governments are delivering on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In a context of existing structural, social, economic and environmental challenges, countries across the world continue to face significant obstacles in reaching the objectives set by the 2030 Agenda. At the same time, geopolitical interests and polarisation are severely undermining the ability of multilateralism to provide global solutions to advance social justice.

In this context, trade unions emphasise the need for a New Social Contract with SDG 8 at its core to respond to workers’ demands for decent, climate-friendly jobs with Just Transition; rights for all workers; minimum living wages and equal pay; universal social protection; equality to end all discrimination; and inclusion of all countries in decision-making processes to build a rights-based development model aligned with the SDGs.

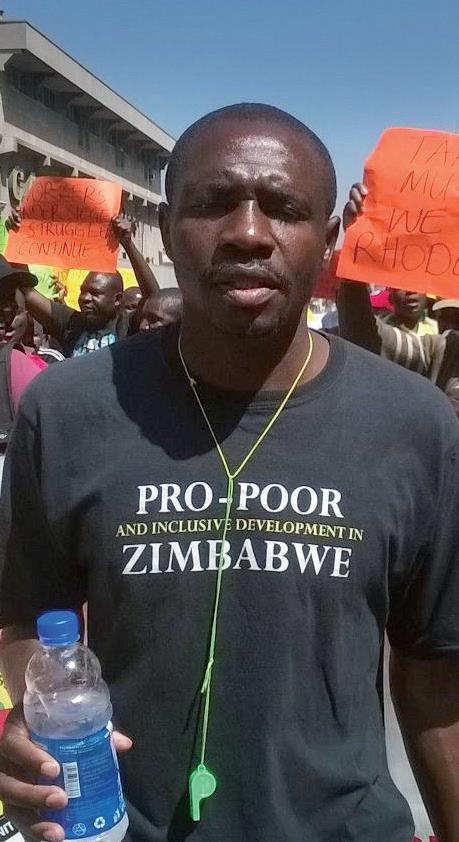

A Trade Union Take on the SDGs compiles findings and analysis of the SDG country reports produced by trade union organisations in 13 countries in 2024: Brazil, Chad, Costa Rica, Kenya, Namibia, Nepal, Nigeria, Peru, South Africa, Spain, Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe. These reports assess the transparency of government processes as well as their engagement in consultations and social dialogue with trade unions to define and implement national SDG plans. They also map countries’ efforts to reach key SDG targets. This work is an essential part of the global labour movement’s contribution to the SDGs Decade of Action.

This year’s review includes trade unions’ reporting on how their governments are responding to multiple, interlinked crises in the years following the Covid-19 pandemic: rising costs of living including food and energy prices; growing inequality; climate change and environmental degradation; and armed conflicts.

The SDG Summit, held under the auspices of the UN General Assembly in September 2023, highlighted how these crises have hindered progress towards the goals and called for urgent action. Although the SDGs are increasingly integrated into national policies, the resources to implement them remain insufficient. Recovery and resilience measures must be human-centred and funded through domestic resource mobilisation and international support. This includes clear commitments to more affordable, long-term financing within a reformed international financial system1

Decent work is a key driver for progress across all the other SDGs. Trade unions, as an organised and democratic expression of working people, are uniquely placed to help formulate, monitor and deliver policies in their countries and internationally. Yet many trade unions report that governments do not adequately include them in the design and implementation of development plans. Stronger social dialogue, based on freedom of association, the right to collective bargaining and the right to strike, is crucial to building trust and delivering equitable and sustainable policies to achieve the 2030 Agenda.

Trade unions assessed the transparency of the SDG implementation process within their countries based on two indicators: (1) their ability to access information and decision-making processes, including consultation meetings, accessibility of policy documents and the openness of relevant officials or institutions and (2) the existence of adequate reporting mechanisms.

In most of the 13 countries surveyed, trade unions reported limitations on access to information. In six of these countries, information is provided at irregular intervals or only when requested. Only two countries (Brazil and Spain) enjoy complete access to information, while in one country (Peru) there is no access at all. In addition, reporting mechanisms are often inadequate.

SDG 17 recognises multistakeholder partnerships as key to achieving the SDGs and calls on countries to set up multistakeholder monitoring frameworks that support the achievement of the goals. Trade unions have a key role to play in integrating the needs and priorities of workers and society at large into the policy-making process, ensuring that no-one is left behind.

Trade unions assessed existing SDG consultation processes in their countries, with a particular focus on the functioning of multistakeholder consultation platforms. Most of these assessments showed that unions were not included in the fora that governments had set up to monitor and implement the 2030 Agenda in their respective countries. Either there is no multi-stakeholder platform or trade unions are not included in it. In several countries, input only takes place via a national labour council. Full SDG consultation processes are in place in only three of the countries surveyed (Brazil, South Africa and Spain).

A sustainable future for people and planet can only be achieved with decent work and social justice. Social dialogue is a fundamental means of implementing the 2030 Agenda as it facilitates consensus building among governments, employers’ and workers’ organisations on policies that have an impact on decent work strategies. However, the trade union analysis reveals insufficient integration of social dialogue into national SDG planning and implementation processes.

A tripartite dialogue on the 2030 Agenda has been reported as working effectively in only three of the countries surveyed (Brazil, South Africa and Spain). Where trade unions were able to make contributions to national government, these were rarely drafted jointly with employers’ representatives (Tanzania being one exception). Furthermore, discussions usually focused on the implementation of SDG 8, rather than the 2030 Agenda as a whole. In three of the countries surveyed (Chad, Kenya and Peru), social partners were not involved at all in the design and implementation of their government’s national SDG plan.

Inequality of wealth distribution is still of concern in all the countries in this report. Progress in reducing inequality slowed and in some cases reversed following the Covid-19 pandemic.

Of the countries surveyed, eight are in sub-Saharan Africa, with income classifications ranging from low to upper middle. All these countries report significant challenges to achieving greater equality, with Chad, Uganda and Zimbabwe as examples of where the gap is widening.

Latin America is also one of the most unequal regions in the world. Of the three countries surveyed on the continent, all are classified as uppermiddle income but are still very unequal. Worryingly, trade unions report that inequality is increasing in Costa Rica (formerly one of the most equal societies in the region) and Peru.

Tackling unemployment and in-work poverty, while promoting productive employment and labour income share is key to employment quality. Unemployment levels have recovered since the pandemic in most of the countries surveyed. However, in some countries, securing employment remains a challenge with young people most affected, notably in southern Africa (Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe) and Nepal. Trade unions in countries such as Nigeria, Tanzania and Uganda report a reality of underemployment among the working population.

Women continue to do more unpaid work than men and experience a gender pay gap in all countries surveyed. Female representation in managerial positions or parliamentary seats has only improved in some of the countries.

Minimum wages can help to combat poverty and reduce inequality. Nepal and Spain recently increased their minimum wage. Other countries either have no minimum wage (including Namibia, Peru and Uganda) or have experienced delays in implementation (Kenya) or negotiation (Nigeria).

Labour vulnerability reflects the exposure of workers to risks and an absence of social protection.

The share of informal and vulnerable work is high in all low- and medium-income countries in the report and even more so for women. Levels of precarious employment are also very high in Spain and increasing in Costa Rica.

Reducing the number of young people not in education, employment or training (NEET) remains a challenge across the board. Young women are more likely to be NEET than young men.

Social protection is crucial for economic recovery and resilient societies. Social protection coverage and access to essential services tend to increase with the income level of the country. However, government policies also impact progress. Costa Rica, for example, has cut spending on essential services and social security and seen an increase in the number of people in poverty. In Spain, the only high-income country in the report, not enough people who are unemployed, or in vulnerable employment receive benefits. High levels of corruption have diverted funds in Nigeria and Peru.

Trade unions report labour rights violations in almost all countries surveyed, even when international conventions have been ratified. Even more worryingly, the situation is deteriorating in countries such as Costa Rica, Peru and Uganda. Spain has seen improvement thanks to the removal of the law restricting the right to strike and protest.

Labour inspectorates are understaffed in almost all countries when data is available, although more inspectors are being recruited in Brazil and South Africa.

Child labour is still a major concern in nearly all the African countries surveyed. It remains a problem in Nepal and in certain sectors in Peru.

To address the multiple ongoing crises, trade unions call for the application of a New Social Contract, reflected in national policies.

Specifically, they call for:

• A renewed political commitment to the objectives of the 2030 Agenda. This should be achieved through effectively mainstreaming the SDGs into national development plans and budgets with adequate financial resources, including progressive taxation and Official Development Assistance (ODA) to support sustainable development efforts.

• Investments in the creation of decent, sustainable and climate-friendly jobs, as well as lifelong learning, especially in the context of green and digital transitions, as well as investments into clean energy and the care economy.

• The implementation of a labour protection floor for all, ensuring respect for labour rights for all workers regardless of contractual status, occupational health and safety, and establishing minimum living wages. In addition, freedom of association, collective bargaining and the right to strike must be secured; migrant workers should have full access to labour markets and rights-based pathways to permanent residency.

• Universal social protection, to invest in coverage for the three-quarters of the world’s people who are fully or partly denied this basic human right, starting with a global social protection fund.

• Equality in the workplace and in society by guaranteeing equal pay for work of equal value and ending all discrimination, whether based on sex, class, ethnicity, age, ideology, religion and sexual orientation. To achieve this, it is imperative to invest in public care services to reduce and redistribute unpaid care.

• Ensuring inclusive governance, democracy and social dialogue by reinforcing the role of social dialogue is a key means of implementation of the 2030 Agenda. Social partners must be involved in a genuine consultation process on the development of national plans for the implementation of the SDGs; to this end, transparent progress reporting is essential. At the same time, social dialogue must be recognised as a governance tool for the SDGs at the international level, and social partners must be meaningfully involved in the construction of a multilateral system based on human rights, solidarity and democracy.

DEMAND A NEW SOCIAL CONTRACT

The Brazilian government has launched several programmes to address multiple ongoing crises. These include policies to fight hunger by increasing production and supply, an ecological transformation programme for energy transition and reducing carbon emissions, and climate change mitigation and adaptation programmes. Trade unions also report that the Brazilian government is actively working towards achieving the objectives of SDG 8. To this end, it has put in place a reindustrialisation policy; policies to promote productive organisation, technical advice, formalisation and access to credit to small and medium enterprises as well as an environmental transformation policy combined with efforts to create decent jobs. Furthermore, the government has approved an equal pay law; strengthened the apprenticeships programme as well as policies encouraging youth training and reformulated the quota programme at universities; it is further combatting the abuse of workers by strengthening labour inspection capacities.

Trade unions note that the previous two Brazilian governments (Tenmer 20162018, and Bolsonaro 2019-2022) abandoned efforts to implement the SDGs. However, President Lula’s government is committed to restarting the process and plans to present an updated VNR.

As a result, all ministries are required to integrate the SDGs into their work, coordinated by an executive secretariat under the presidency’s general secretariat. The Institute for Applied Economic Research (IPEA), the Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), and the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ) handle data collection and monitoring. Budget resources are allocated to achieve SDG goals and support civil society participation.

The current government has decided to reinstate the National Commission for Sustainable Development Objectives (CNODS). As the commission has only recently been relaunched, its format is still to be defined and it is thus difficult to assess its transparency. However, the format of the commission and its future work programme has been consulted with civil society, including trade unions, on the one side, and relevant ministries on the other. One of the commission’s objectives will be to provide transparency to actions related to the SDGs, such as consulting on the implementation of related actions and consolidating public reporting on the topic. Trade unions have been invited to be active participants in the forthcoming discussions of the commission, which will focus on delivering on all SDGs, not just SDG 8.

Complete access to information

There is a structured consultation/ multi-stakeholder platform

There are tripartite instances to implement and monitor the SDGs involving social partners and governments

For SDG 1, indicators for target 1.1 (eradicating extreme poverty) show that more efforts are needed, as 5.8 per cent of the population was still living below the extreme poverty line in 2021. Additionally, 2.5 per cent of the country’s workers and their families lived on less than USD 1.90 per person per day in 2023. This is extremely worrying, considering that with an HDI of 0.754, Brazil is considered an upper-middleincome country. However, with regards to target 1.3 (nationally appropriate social protection systems), in 2021, 72.7 per cent of the population benefitted from some type of social security benefit, and all of those in poverty were covered by the social protection system. On target 1.a.2 (essential services) in 2017, spending on social protection (excluding health) stood at 15.7 per cent.

For SDG 5, more efforts are needed to achieve target 5.4 (recognise and value unpaid care and domestic work), as women spent nearly twice as much time (21.4 hours a week) on unpaid domestic and care work as men (11 hours a week) in 2019. With regards to target 5.5 (women’s full and effective participation), while the proportion of seats held by women in parliament increased from 5.7 per cent in 2000 to 17.7 per cent in 2023, it remains exceedingly low.

Further efforts need to be made on SDG 8. Progress on target 8.3 (support decent job creation) is needed, as informal employment outside of agriculture remains high – standing at 56.3 per cent (57.4 per cent among men and 47.9 per cent among women) in 2020. Additionally, the rate of vulnerable employment stood at 53.6 per cent in 2021. On target 8.5 (full and productive employment and decent work for all), the unemployment rate stood at 7.7 per cent in 2023, affecting more women (9.3 per cent) than men (6.4 per cent). At 20.4 per cent, the gender pay gap is also worrying. In this context, the approval in July 2023 of a law requiring private legal entities with 100 or more employees to guarantee equal salary and compensation criteria for women and men exercising the same position and undertaking work of equal value is highly welcome. NEET indicators for target 8.6 (reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education or training) stood at 21 per cent in 2022 – the majority of this group comes from the country’s poor (61.2 per cent) and extremely poor (14.8 per cent) populations. Indicators for target 8.7 (eradicate forced labour and the worst forms of child labour) suggest that 4.6 per cent of children aged 5-17 engaged in child labour in 2019. With regards to target 8.8 (protect labour rights

and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers), trade unions report an insufficient number of trained labour inspectors. In 2020, 27 violations of labour rights were noted – 15 in law and 12 in practice.

With regards to SDG 10, target 10.4 (progressively achieve greater equality) reveals startling levels of inequality. In 2023, 10 per cent of the highest income earners controlled 42.7 per cent of GDP, while the lowest 20 per cent controlled 2.8 per cent of GDP. The labour share of GDP stood at 63.1 per cent in 2023. On target 10.7 (migration and mobility), trade unions participate in a national commission evaluating policies for migrant workers.

On SDG 13 and target 13.2 (integrate climate change measures into policies), trade unions report that the government has launched an Ecological Transformation Plan, which aims to promote a new model of sustainable development, just transition as well as combat climate change and its effects. The Plan aims to do so through measures such as a regulated carbon market, the issuing of sustainable sovereign bonds and a national taxonomy focused on sustainability.

On SDG 16, Brazil is far off reaching target 16.10 (protect fundamental freedoms), as there is no guarantee of workers’ rights. Although Brazil has ratified Convention No. 98 on the Right to Organise and Collective Bargaining in 1952, it has not ratified Convention No. 87 on Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise (1948).

Trade unions call on the Brazilian government to:

• Focus on the creation of quality jobs.

• Ensure that labour rights are respected.

• Open a debate on the employment targets set by the re-industrialisation programme.

• Expand social protection for workers in all sectors.

• Implement the law on equal pay between men and women and the equal pay plan.

• Resume the operations of the National Labour Council, tripartite and other spaces for social dialogue in different sectors.

• Create a social participation system that facilitates coherent and effective monitoring of the SDGs across the various bodies involved in implementing the 2030 Agenda.

• Support the Brazilian government’s initiative to include racial equality as the eighteenth SDG.

Multiple crises, including humanitarian and security challenges, arising from both the Russia-Ukraine war and climate change – which caused serious flooding in 2022 - have affected SDG progress in Chad. The government declared a state of emergency in response to severe food insecurity and malnutrition in 2022 and 2024. Relief measures included a National Solidarity and Support Fund to increase food stocks, and fiscal reductions, primarily on food products. A national Covid-19 plan was adopted in response to the pandemic, and water and electricity were provided free-of-charge for a limited period during 2020. Trade unions were not associated with any of these measures, however.

Trade unions report that while there is no government policy specifically aimed at achieving SDG 8 (inclusive and sustainable growth, employment and decent work), other policies and strategies do contribute to it. These include the Master Plan for Industrialisation and Diversification of the Economy (PDIDE), the African Continental Free Trade Area implementation strategy, and national strategies on social protection and private sector development. A programme to boost entrepreneurship launched in 2023 provides CAF 30 billion in funding, as well as tax relief measures, for small businesses.

Chad’s long-term national development strategy Vision 2030 is implemented through national development plans (NDPs) that integrate the SDGs into national priorities. The first NDP ran from 2017 to 2021, but was extended to 2023 due to delays in implementation. The Ministry of the Economy, Planning and International Cooperation has the overall responsibility for the NDP, implemented through the sectorial ministries.

In 2022, petroleum export receipts were expected to double, and Chad reached an agreement with its creditors under the G20 Common Framework that will reduce its risk of debt distress to a moderate level by the end of 2024. However,

these developments have not yet translated into increased funding for the SDGs. Following the death of former President Idriss Déby in 2021, roadmaps for political transition have focused on restoring constitutional order, security and electoral stability, thus diverting resources from development programmes.

Civil society organisations are in theory involved in formulating and evaluating national policies to implement the SDGs, as required by development partners. However, this is not always effective. Consultations are centralised within ministries, with no local coordination to encourage trade union participation. There is no national dialogue with the United Nations Resident Coordinator.

Regular access to limited information

There are information sessions but no interaction

No involvement of social partners by the national government on SDG national plan definition and implementation

With a human development index (HDI) of 0.394 and ranking 190th out of 191, Chad is one of the world’s least developed countries. At least one third of the population live below the international poverty threshold of USD 2.15 a day. The country is not on track to meet target 1.1 (eradicating extreme poverty). Social protection systems (target 1.3) are almost non-existent. Access to essential services (target 1.a.2) is low but improving: in 2022 the proportion of the population using basic drinking water services increased to 52 per cent and sanitation services to 12.9 per cent. The proportion of total government spending on essential education services increased to 15.1 per cent in 2021.

Chad has enshrined gender equality in the transitional constitution and ratified international and regional treaties. However, major challenges remain in practice: too many females are married before 18; experience violence including genital mutilation; and cannot complete their primary education. For many indicators, including target 5.4 (recognise and value unpaid care and domestic work), recent data are unavailable. The ratio of female to male labour force participation was 68 per cent in 2022. Progress is being made on target 5.5 (women’s full and effective participation) as the proportion of women in the National Transitional Council increased to 25.9 per cent in 2022.

In 2022, 76 per cent of Chad’s population were estimated to live in rural areas. With regard to target 8.3 (support decent job creation), 90 per cent of nonagricultural jobs were deemed informal in 2018, and 91 per cent of all jobs were deemed precarious or vulnerable in 2021. Latest national statistics under target 8.5 (full and productive employment and decent work for all) show that the official unemployment rate stands at 2 per cent, the expanded unemployment rate at 18.5 per cent, and underemployment at 4 per cent. Chad has a young population with 81 per cent under the age of 34. On target 8.6 (reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education or training), the NEET

rate for 15- to 24-year-olds was 37 per cent in 2018, with a higher rate for females (46 per cent) than males (25 per cent). Much work remains to meet target 8.7 (eradicate forced labour and the worst forms of child labour). The latest figures indicate that 39 per cent of children aged 5 to 17 are engaged in child labour. On target 8.8 (protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers), no recent data are available on the number of accidents or labour inspectors. Chad has ratified ILO conventions 87 and 98 on freedom of association and collective bargaining.

On SDG 10, the labour income share as a percentage of GDP decreased to 42.4 per cent in 2020, indicating there is still much to be done to achieve target 10.4 (progressively achieve greater equality). Chad has a statutory minimum living wage of CAF 60,000. The governance framework to meet target 10.7 (migration and mobility) is evolving positively, with action plans in place. Chad faces a wide range of migration flows, including displaced people from neighbouring countries, and human trafficking is a particular challenge. Progress is hampered by insufficient migration data and there is scope for greater involvement of social partners in migration policies.

Chad’s geographical and landlocked location makes it especially vulnerable to climate change. Under SDG indicator 13.2 (integrate climate change measures into policies), Chad has a UN-supported National Adaptation Plan in place.

On SDG 16, with regard to target 16.10 (protect fundamental freedoms) in 2023 Chad was deemed to have systematic violations of rights under the ITUC Global Rights Index and its press freedom score had decreased to 54 out of 100.

Trade unions repeat their call on the government of Chad to:

• Consolidate social dialogue processes and structures for the implementation of the SDGs and in crisis response strategies.

• Provide specific support to MSMEs and informal economy units, particularly in the Agri-food sector.

• Implement the national strategy for the elimination of the country’s internal and external debt.

• Strengthen and extend social protection and ensure universal access to health care.

• Integrate SDG funding for each ministry concerned into the State’s general budget.

• Provide for open participation in the national coordination structure on the SDGs to trade unions as well as local and rural organisations to promote ownership and local non-governmental participation.

• Decentralise the parliamentary commission on the follow-up and evaluation of the SDGs to bring the Goals closer to the local level throughout the country.

• Implement the communication strategies to promote the SDGs.

• Prioritise partnership agreements on development projects which promote sustainable development.

The structural reforms introduced in Costa Rica in the 1980s have led to increased liberalisation and reduced social spending. The tax reform of 2018 deepened inequality and limited the country’s capacity to respond to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. The government has pressed ahead with the policy of social disinvestment, which is seriously affecting public services and national development programmes (education, health, housing, etc.), and is incompatible with the 2030 Agenda.

With its Public Employment Framework Law, the government limited rights, benefits and salaries in the public sector, which have been frozen for almost five years now. This, coupled with inflation, has led to a loss of purchasing power of close to 20 per cent. The bipartite Public Sector Wages Commission was arbitrarily dissolved in 2019.

SDG 8 has also been impacted. The government has not adopted a comprehensive national policy on employment, formalisation and decent work, and has weakened social protection and trade union rights, with constant violations of ILO Conventions. A bill to raise working hours to 12 hours a day eliminates the right to an 8-hour workday in various sectors, increases occupational hazards and above all impacts women and work-life balance.

The National Pact for the SDGs brings together all the main stakeholders involved in SDG implementation. Political coordination takes place through the High Level Council (Presidency of the Republic and three ministries). There is a Consultative Committee (representatives of the signatories of the Pact, including the trade unions), but it does not engage in a real process of social dialogue or plural consultation for the drafting of the voluntary reviews.

The trade unions report that the theoretical SDG commitments are not supported by public policies, budgets, social investment and political will. The Ministry of National Planning and Economic Policy asks other ministries and actors to make contributions on activities they undertake to achieve the SDGs, and it assembles the reports in this way, without any linkages or real impact through coherent and integrative public policies.

There is no real social dialogue process. The existing tripartite structures are ineffective with regard to the SDGs. Trade unions report that they are not able to influence the adoption of policies for decent work, economic and social protection, and strengthening the human and labour rights framework. Trade unions and other actors are excluded from analysing, discussing and assessing government policies to ensure accountability and their relevance and impact in terms of achieving the SDGs. Nor does the Ministry of Labour feature in the roadmap.

The mechanisms for preparing and presenting the voluntary reviews are inadequate. As regards SDG 8, trade unions are calling for the adoption of the ILO’s decent work indicators.

With regard to SDG target 1.1 (extreme poverty), Costa Rica’s good human development indicator is at high risk (index HDI of 0.8), as is the relatively low percentage of people living below the international poverty line. GDP growth and associated socioeconomic indicators, including poverty rates, have recovered slightly but not sufficiently since the pandemic. On target 1.3 (nationally appropriate social protection systems), 60.5 per cent of the population and 81.2 per cent of poor people were covered by social protection systems in 2021, but the government’s management of social security is seriously lacking, with an increase of 30 per cent in the state’s trillion-dollar debt and arrears owed to social security. Access to essential services (target 1.a.2) in Costa Rica is threatened by the cuts to education, health and social protection budgets: government social spending dropped to 9.7 per cent of GDP in 2022. The education budget was reduced from the constitutional 8 per cent to 5.2 per cent of GDP in 2024.

Social, wage and employment gender gaps persist. Women spent twice as much time (32 hours per week) as men on unpaid domestic and care work (target 5.4), according to the National Time Use Survey (ENUT) 2022.

Regarding target 8.3 (support decent job creation), the informal economy reached 37 per cent in 2023. On target 8.5 (full and productive employment and decent work for all), unemployment fell to 8.5 per cent in 2023, due to a fall in the labour force participation rate from 59 per cent to 56 per cent. Women are more likely to be unemployed or underemployed. Target 8.6 (reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education or training) requires greater efforts, as 21 per cent of young people were NEET in 2023. Costa Rica has taken steps to eradicate child labour (target 8.7), which stood at 1.3 per cent in 2021. Target 8.8 (protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers) is far from being met. Anti-strike laws, public employment and public finance laws restrict trade union rights and collective bargaining, in a clear breach of ILO Conventions 87 and 98,

as the ILO’s own supervisory system has documented. The number of labour inspectors is very low (0.6 inspectors per 10,000 workers in 2020), with insufficient legislation, as highlighted by the ILO.

Target 10.4 (progressively achieve greater equality) is of concern, as Costa Rica is one of the most unequal countries in Latin America and the most unequal in the OECD.

On target 13.2 (integrate climate change measures into policies), Costa Rica pledged to establish a Just Transition governance scheme including tripartite social dialogue, to develop a Just Transition Strategy by 2024, accompanied by a national green jobs policy and mechanisms to monitor and evaluate them. This pledge has not yet been fulfilled. Trade unions are excluded from any dialogue in this field, as well as from consultation for the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) reports.

The situation is worsening with regard to target 16.10 (protect fundamental freedoms). In 2024, Costa Rica was deemed to have regular violations of rights under the Global Rights Index, and it has fallen several places in the World Press Freedom Index. President Chaves maintains an authoritarian stance towards the parliamentary opposition, public institutions, the media and judiciary. Cuts to public services and citizen security have led to serious increases in organised crime, drug trafficking and institutional corruption.

Trade unions call on the Costa Rican government to:

• Establish coherent policies, programmes and budgets to achieve the SDGs.

• Deepen the work with the Advisory Committee, and make better use of technical cooperation with the UN and ILO.

• Adopt a comprehensive national employment policy formulated through tripartite consultation.

• Integrate decent work into economic growth, poverty reduction and hunger prevention policies.

• Repeal anti-worker laws and legislate to guarantee trade union rights and freedoms, the fundamental labour rights.

• Ratify and comply with ILO Conventions.

• Strengthen social protection systems to combat persistent social inequality.

• Revoke fiscal austerity, legislate against tax evasion and avoidance, and undertake progressive tax reforms.

• Adopt a living wage policy that ensures families’ economic security.

• Improve funding and management to reduce waiting lists, as well as the debt with the social security fund.

• Promote gender equality and equity through laws, programmes and gender mainstreaming policies, giving weight to decent work for women in all economic sectors.

• Strengthen meaningful social dialogue in existing national and sectoral fora, and reactivate the Economic and Social Advisory Council.

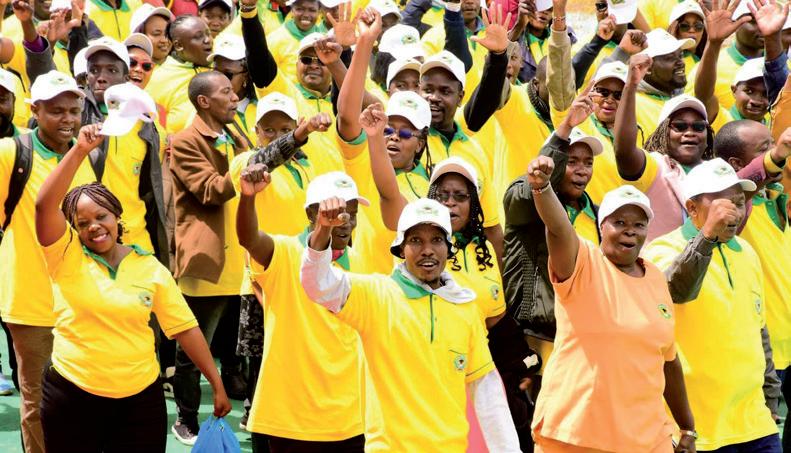

Trade unions were involved in measures to mitigate the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. These included a tripartite memorandum of understanding with workers and employers, to protect jobs and help retrenched workers back into employment during the recovery.

Since coming to office in 2022, the Kenya Kwanza government has introduced new taxes in order to tackle Kenya’s high level of national debt. However, opposition from trade unions and public protests have recently led to some of these proposed taxes being scrapped, to protect Kenyans from the increasing cost of living.

Trade unions have not been involved in developing measures to face the food, energy and climate crises, however. They have been advocating for changes in acts of parliament to allow trade union representation on strategic energy and climate boards, for instance, Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Authority (EPRA) and the National Climate Change Council (NCCC).

Dialogue with social partners is focused on SDG 8, primarily through the development and implementation of the Decent Work Country Program under the Ministry of Labour and Social Protection.

Article 43 of the Kenyan Constitution on Economic and Social Rights states that the government must ensure its policies and development plans promote SDGs. The Kenyan government implements the 2030 Agenda through its Vision 2030 strategy, rolled out in five-year Medium-Term Plans (MTPs). The MTP “Bottom Up Economic Transformation Agenda for Inclusive Growth” (BETA), together with the County Integrated Plan, cover the period 2023-2027. The State Department for Economic Planning under the Treasury is responsible for coordinating implementation and monitoring of the SDGs.

Following elections in 2022, Kenya’s new government has created new state departments and provided resources to implement the SDGs. Kenya has also

recently signed new trade agreements with the EU and US, in which the SDGs have been given prominence. However, trade unions report a reality of insufficient budgets for government ministries to achieve the Goals, partly driven by increased debt servicing costs. Reporting on SDGs is inadequate, particularly given recent changes in the coordinating ministries.

There is a multi-stakeholder platform, the SDGs Kenya Forum, that includes civil society organisations but not trade unions. Trade unions are therefore not consulted by the government during the preparation of the UN Voluntary National Review. They are making efforts to meet with the UN Resident Coordinator.

Irregular access to limited information Informal or ad hoc consultation No involvement of social partners

Kenya’s human development index (HDI) has increased to a medium level of 0.6, however serious challenges remain to meet target 1.1 (eradicate extreme poverty): 36.1 per cent of the population lived below the international poverty line of USD 2.15/day in 2021, and 26 per cent of the population were deemed working poor in 2023. The proportion of the population covered by social protection systems (target 1.3) remains low: only 7.2 per cent of the population were covered by at least one benefit in 2021. However, in 2023-24, Kenya revised its National Social Protection Policy, introduced a new Social Protection Bill, and significantly increased affirmative action funding. Spending on essential services (target 1.a.2), including health, education, social protection, and water and sanitation, was 23.6 per cent of the total national budget in 2022-23, representing only 6.06 per cent of GDP.

On gender equality, more work is to be done. Kenya’s first-ever Time Use Survey in 2023 showed that that, on average, women spend approximately five hours a day on unpaid care and domestic work (target 5.4) while men spend only one hour. On target 5.5 (women’s full and effective participation), women held 49.6 per cent of managerial positions in 2019 and 23.3 per cent of parliamentary seats in 2023. A recent (2023) assessment of gender budgeting in public finance management reported poor performance.

With regard to target 8.3 (support decent job creation), 86.5 per cent of all jobs were deemed informal in 2019, and 60 per cent deemed vulnerable in 2022. There is still progress to be made in achieving target 8.5 (full and productive employment and decent work for all). Females are more likely to be unemployed and underpaid than men. The proportion of youth not in employment, education or training (target 8.6) was 18.7 per cent (25 per cent of females versus 12.2 per cent of males) in 2021. Kenya still faces challenges

to meet target 8.7 (eradicate forced labour and the worst forms of child labour). Despite initiatives including the Children’s Act 2022 and more worksite inspections, the ILO reports that child labour and trafficking continue to be significant problems. Target 8.8 (protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers) is still far off being met. Kenya scored 4.38 (10 being the worst) for reported labour rights violations in 2020. According to government figures, there were 6979 occupational accidents and 380 fatalities in 2023. There is a shortage of labour inspectors, despite recruitment efforts. Kenya has ratified ILO Convention 98 on collective bargaining, but not Convention 87 on freedom of association.

Kenya has high levels of inequality and is not on track to meet target 10.4 (progressively achieve greater equality): labour income share of GDP fell to 36 per cent in 2021, with 31.8 per cent of overall GDP held by the top 10 per cent of income earners compared to only 7.2 per cent of GDP held by the bottom 20 per cent. Kenya has established minimum wage councils which are yet to be operationalised. Social partners are involved in migration policy development in Kenya under target 10.7 (migration and mobility)

Trade unions report ongoing efforts to be involved in national and sectoral dialogues to achieve a Just Transition under target 13.2 (integrate climate change measures into policies)

More progress is needed on target 16.10 (protect fundamental freedoms). In 2024 Kenya was reported as having systematic violations of rights.

Trade unions call on the Kenyan government to:

• Involve trade unions more closely in SDG implementation.

• Ensure that devolution to counties works more effectively and that better data gathering and reporting take place.

• Increase budgets to key ministries delivering on the SDGs, including Labour, Health, Climate, and Devolution.

• Support job creation with greater investment in TVETS and involving trade unions in policy discussions and reviews on employment.

• On social protection, increase coverage and public confidence in the National Social Security Fund.

• Strengthen the Ministry of Labour’s capacity to ensure compliance with the minimum wage law.

• Enforce existing labour rights laws by ensuring the Ministry of Labour has sufficient human resources and budget.

• Promote social dialogue by investing in the National Labour Board.

To address the multiple crises, the government of Namibia has decided to intervene in key areas: employment creation, prioritising youth employment and entrepreneurship; expanding social protection coverage; and a national formalisation strategy. Trade unions have been actively involved in the implementation of these initiatives. This follows up on several stimulus and relief measures to directly support individuals, small and medium-sized enterprises and corporations, and safeguard jobs introduced in response to the COVID-19 crisis. At the time, employment retention measures were undertaken through the flexibilisation of labour regulations, oriented to avoid major retrenchments and closures of businesses. Trade unions note that these have not yielded the expected results, as many people have lost their jobs and salaries, and hours of work were cut unilaterally, with workers forced to go on unpaid leave.

To combat the climate crisis, in 2021 Namibia pledged to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 91% compared to the business-as-usual scenario. The plan identifies key sectors such as energy, water resources, coastal resources, human settlements and urban planning, agriculture, and forestry, developing targeted strategies for each. In addition, the government foresees increasing the share of renewable energy use. However, the overall reduction is conditional on international financial support, without which the country can only guarantee a 14 per cent reduction.

The government developed its current National Development Plan (NDP 5) before the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) in 2015. As a result, the NDP is not well aligned with the objectives of the 2030 Agenda. Trade unions suggest that this has led to critical SDGs receiving little or no attention. While preparations for the drafting of the next National Development Plan (NDP 6) are ongoing, trade unions warn that there is little indication of this being adequately aligned with the SDGs. National development and the implementation of the SDGs are overseen by the National Planning Commission (NPC) in the office of the president. The director of the NPC is designated as a principal advisor to the president on economic and development planning.

Trade unions report that there is no transparent monitoring or evaluation of the implementation of the SDGs, with the government relying primarily on input from the national statistics agency. Trade unions have provided input towards the development of NDP 6, but based on the white paper released by the government in 2024, do not

believe that their recommendations were considered. While the government has recently announced that it would take a bottom-up approach of consulting plans directly with communities, with findings then validated with national stakeholders, it remains to be seen how this mechanism works out in practice.

Social partners are engaged in a dialogue on socio-economic development but not on the SDGs. However, implementation of SDG 8 has improved thanks to Namibia becoming a pathfinder country of the Global Accelerator on jobs and social protection for just transition. Thanks to this process, trade unions have been able to engage with the government at least on an ad hoc basis.

Trade unions report that no specific resources have been allocated to the implementation of the SDGs aside from those allocated towards the NDP and the acceleration action plan, the Harambee Prosperity Plan. An analysis of the budget demonstrates that only 35.5 per cent of the SDG indicators are covered by the NDP and existing budget lines.

Irregular

There

There are individual contributions from social partners to the national government

In 2023, 11 per cent of workers in Namibia were living under the poverty line, an increase from 10.9 per cent in 2019. This, together with a drop of 12 places in the human development index (HDI) ranking from 2019 to 2022 suggests a regression in meeting target 1.1 (eradicate extreme poverty). On target 1.3 (nationally appropriate social protection systems), 27.2 per cent of the population had access to either direct or indirect social protection benefits in 2016. However, the services are unevenly applied and difficult to access for the rural and poorest sectors of the population.

In 2024, women’s labour market participation was lower (54.1 per cent) than men’s (61.2 per cent) which may correlate with their greater responsibilities for performing more unpaid domestic work, suggesting that further efforts are needed to achieve progress on target 5.4 (recognise and value unpaid care and domestic work). With regard to target 5.5 (ensure women’s full and effective participation), in 2023, 38.5 per cent of Namibia’s parliamentarians were women; the representation of women in senior and middle managerial positions stood at 48.2 per cent in 2018. However, Namibia’s budget is not gender responsive, allocating the fewest resources to the sectors which overwhelmingly employ women – agriculture and SMEs.

There are serious concerns about Namibia meeting the targets set by SDG 8 (decent work). The proportion of informal employment outside of agriculture stood at 47 per cent in 2018, with more women (50.4 per cent) than men (43.4 per cent) being informally employed. In addition, the share of vulnerable employment stood at 32 per cent in 2022. This suggests further efforts are needed to meet target 8.3 (support decent job creation). On target 8.5 (full and productive employment and decent work for all), the 2018 unemployment rate stood at 19.9 per cent, with young people (15-24) being particularly impacted (38 per cent). In addition, NEET indicators for target 8.6 (reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education or training) stood at 31.8 per cent of youth aged 15-24 in 2018, with young women being more affected (34.2 per cent)

than men (29.3 per cent). Indicators for target 8.7 (eradicate forced labour and the worst forms of child labour) are extremely worrying, as the high rates (16 per cent) of multidimensional poverty suffered by children in Namibia cause them to engage in child labour including its worst forms, such as commercial sexual exploitation. Target 8.8 (protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers) is far from being met, as in 2016 there were only 61 trained labour inspectors for a working population of nearly 680,000 in the country. In addition, there are limitations on the rights to freedom of association and collective bargaining, as certain sectors of workers are prevented from joining trade unions or entering into collective bargaining agreements.

Progress remains to be made for Namibia to reach target 10.4 (progressively achieve greater equality), as in 2015, the top 10 per cent of income earners had a 47.3 per cent share of GDP, with the bottom 20 per cent of income earners holding a paltry 2.8 per cent share. The absence of a national minimum wage and high levels of informal employment are the principal driving factors of inequality in Namibia. With regard to target 10.7 (facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people), Namibia adopted a National Labour Migration Policy in 2020, due to be implemented as of 2025. As a result, trade unions and employer federations launched a bipartite network to work towards the elimination of all forms of discrimination against migrant workers.

On SDG 16, Namibia is far off reaching target 16.10 (protect fundamental freedoms), as trade unions which are not affiliated to the ruling party are routinely discriminated against or denied the right to register their activities.

Trade unions call on the Namibian government to:

• Put in place effective measures to mitigate global crises and their impacts on the economy.

• Strengthen and extend social protection (e.g. pensions, basic income) and ensure universal access to healthcare.

• Adopt a pro-employment and gender-responsive budgeting approach across all fiscal planning processes.

• Adopt policies for a wage-led growth, making wages commensurable to living conditions to increase demand.

• Adopt monetary policies that encourage employment creation, reducing the interest rate for loans in proportion to the number of jobs created.

• Prioritise social dialogue for the implementation of the SDGs by establishing a national tripartite dialogue on the SDGs, together with a co-ordinating task force.

• Set up a focal point in each ministry responsible for mainstreaming, monitoring and reporting on the progress or challenges in the implementation of the relevant SDGs and targets.

• Set up a reporting mechanism on the SDGs, with quarterly reporting sessions, open for participation to trade unions.

Funded by 16 development partners, including international financial institutions, Nepal adopted the Green, Resilient and Inclusive Development (GRID) approach, which aims to simultaneously tackle interlinked challenges: economic recovery from Covid-19; climate change and environmental degradation; and persistent poverty and social exclusion.

While Nepal has developed an ambitious Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the Paris Agreement, in addition to its National Climate Change Policy (2019); Long-term Strategy for Net-Zero Emissions (2021); and National Adaptation Plan (2023), such NDC was never implemented

Until now, trade unions have not been included in developing climate policies, and the Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security (MoLESS) is not included in the NDC high-level steering committee. In March 2024, Nepal became a pathfinder country for implementing the UN Global Accelerator (GA) on jobs and social protection for just transitions. Trade unions deem that there must be alignment/coherence between the GA and national policies and programmes related to climate, decent work and social protection.

The 16th National Development Plan will be implemented from 2024/5 to 2029/30. It sets out the medium-term development vision for Nepal, under its Long-Term Vision 2043. SDGs are integrated into the plan and programme budgets. Nepal published the review “SDG Status and Roadmap 2016-30” in 2017.

The National Planning Commission of Nepal (NPC) is the lead agency for SDG integration, with all ministries responsible for implementation. Budget allocation for SDG implementation is insufficient, and reporting and coordination could be improved. On SDG 8, the MoLESS has established a desk for SDG integration with labour policies and programmes, but this is also underfunded.

Trade unions are not consulted in SDG decision-making and implementation, as they are not represented in the multi-stakeholder forum. Trade unions’ input is focused on issues related to workers. The Central Labour Advisory Council is the principal high-level mechanism for tripartite social dialogue, but it does not function well.

Irregular access to limited information

Between Information sessions but no interaction; and Informal or ad hoc consultation

Individual contributions from social partners to the national government

Nepal has a medium level of human development index (HDI) with a value of 0.6. The proportion of the population living in extreme poverty (target 1.1) on less than USD 2.15 per day is estimated to have fallen to 3.25 per cent in 2024. However, 20 per cent of the population were living below the new national poverty line in 2023. The proportion of the population covered by at least one social protection benefit (target 1.3) is 32.9 per cent, while only 16.9 per cent have access to income support. Nepal is making efforts to expand social protection and simplify the complex system. With regard to spending on essential services (target 1.a.2), an analysis of public finances for 2023-24 reveals that social sector allocations make up 29 to 30 per cent of the total budget, with expenditure on health decreasing to 6 per cent, education remaining at 11 per cent, and social protection increasing to 13 per cent.

There are no data available for target 5.4 (unpaid care and domestic work), however the burden falls disproportionately on women, particularly as a high number of men migrate to work abroad. With regard to target 5.5 (women’s full and effective participation), 13.2 per cent of managerial positions were held by women in 2017; while the number of parliamentary seats held by women had increased to 33.1 per cent in 2022. Nepal has adopted gender budgeting, however implementation and monitoring could improve.

Nepal faces challenges to meet SDG 8. Target 8.3 (support decent job creation) is still far off: 77 per cent of the workforce are in informal or vulnerable employment. Gender gaps persist under target 8.5 (full and productive employment and decent work for all), with women more likely to be un- or underemployed, in informal or vulnerable employment. There is a mean monthly earnings gap of NPR 5,834 (approximately USD 46) in favour of men. The proportion of youth not in employment, education or training (target 8.6) is high, standing at

35 per cent in 2017, with females (46 per cent) more affected than males (21 per cent). While child labour is declining under target 8.7 (eradicate forced labour and the worst forms of child labour), the 2018 Nepal Labour Force Survey estimated that 1.1 million children are engaged in labour, predominantly (87 per cent) in the agricultural sector. With regard to Target 8.8 (protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers) Nepal’s overall score on labour rights violations is 3.96 for 2020 (with 10 being the worst). The labour inspectorate is significantly understaffed. Nepal has ratified ILO Convention 98 on collective bargaining and is planning to ratify ILO Conventions 81, 87 and Protocol 29.

The labour share of GDP was 44.1 per cent in 2021, indicating there is still some way to progressively achieve greater equality (target 10.4). Minimum wages in Nepal were last revised in August 2023. Under target 10.7 (migration and mobility), Nepal’s migration policy involves social partners, including trade unions, employers’ organisations, and civil society organisations. The government formed the Foreign Employment Board to help protect the rights of migrant workers.

Engagement with social partners under target 13.2 (integrate climate change measures into policies) should improve as part of the UN Global Accelerator implementation process.

With regard to target 16.10 (protect fundamental freedoms) Nepal is reported as having regular violations of rights in the ITUC Global Rights Index 2024. Fundamental protections are less guaranteed for more vulnerable groups of workers, which include the many Nepalis working abroad in the Gulf and Malaysia; sherpas; transport workers; and street vendors.

Trade unions call on the government of Nepal to:

• Ensure representation of workers and their trade unions in planning and implementation of all SDG and climate policies.

• Invest in decent and climate-friendly jobs and in formalisation of the informal economy. Eliminate outsourcing and other flexible labour arrangements that threaten job security.

• Ensure universal and affordable social protection, including for informal workers. Simplify the complex social security system.

• Establish living wages to allow workers and their families to support their basic needs and sustain a dignified standard of living.

• To achieve equality at work, ratify ILO Convention 190 for a world of work free from violence and harassment. Adopt labour policies that close the gender pay gap, eliminate all forms of discrimination in employment, and create inclusive and safe workplaces for all.

• Uphold the fundamental rights of all workers, regardless of employment arrangements. Ratify ILO Conventions 87, 81, 102, 122, 155, 177, 181, 187, 189, a nd Protocol 29.

• Promote social dialogue by amending the Labour Act to align with the international conventions related to freedom of association and collective bargaining.

#HLPF2024

The Nigerian government is responding to the multiple crises of food and energy prices, climate change and the impact of Covid-19, through its macroeconomic policies in the Economic Sustainability Plan (ESP) and National Development Plan 2021-25 (NDP). Nigeria’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) outlines how the country plans to achieve its climate commitments under the Paris Agreement. Prices for food and fuel remain high. To mitigate the rising cost of living, and in response to trade union demands, the government has been providing wage awards to public sector workers. Tripartite national minimum wage negotiations had not yet reached agreement in June 2024, however. Trade unions report that social dialogue on policies and their implementation is not working effectively. The National Labour Advisory Council (the statutory framework for discussing labour matters) does not meet regularly, and failure to respect agreements reached with workers on several labour matters often leads to strikes.

The Office of the Senior Special Advisor to the President on SDGS (OSSAP-SDGs) is responsible for coordinating, with line ministries, the integration of the SDGs into national priorities. Trade unions report that SDGs are integrated into the NDP to a certain extent.

Progress on implementation and allocation of resources are significantly hindered by corruption and lack of political will. The Nigerian government has established the Federal Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs and Poverty Alleviation. However, in April 2024 the Minister in charge was under investigation for the diversion of public funds to private bank accounts.

Transparency is aided by the Freedom of Information Act. The need for better infrastructure, particularly in rural areas, makes reporting on SDG implementation and communicating to the public more difficult.

While there is a multi-stakeholder platform on the SDGs, trade unions are not involved. Dialogue with them is being facilitated by the ILO through the office of the UN Resident Coordinator, however. Unions regularly provide input to the government on SDG targets, but this is only partially taken on board due to bureaucratic bottlenecks and a negative perception of unions due to their criticism of government policies.

Social dialogue is focused primarily on SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth) as a means of achieving the other SDGs. Unions work with the UN, ILO and other international partners to hold conferences and capacity-building workshops, helping to expand the ILO Decent Work Country Programme and other governance instruments.

Irregular access to limited information

There are information sessions but no interaction

Tripartite instances to implement and monitor the SDGs, involving social partners and governments

Major challenges remain to meet target 1.1 (eradicating extreme poverty) Nigeria’s human development index (HDI) has increased in recent years but remains low at 0.548. Latest figures are that 31 per cent of Nigeria’s population are living below the international poverty threshold of USD 2.15 a day, with 63 per cent in multidimensional poverty. The proportion of the population covered by social protection systems (target 1.3) has increased but remains low at 17 per cent in 2018, with only 1.8 per cent of the vulnerable population receiving cash benefits in 2019 / 10.1 per cent of vulnerable persons covered by social assistance in 2022. Government spending on essential services (target 1.a.2) is very low compared to similar countries: in 2021, less than a quarter of the national budget was allocated to education, health and social protection.

On gender equality, more work is to be done. For target 5.4 (recognise and value unpaid care and domestic work), recent data are unavailable. On target 5.5 (women’s full and effective participation), women made up 57 per cent of middle and senior managers in 2022, but only 3.6 per cent of parliamentarians in 2023. Nigeria is implementing gender budgeting, however a more comprehensive framework would allow greater progress to be made in achieving gender equality targets.

With regard to target 8.3 (support decent job creation), 89 per cent of nonagricultural jobs were deemed informal in Q1 2023, and 84 per cent of employment deemed vulnerable in 2022. There is still some way to go to meet target 8.5 (full and productive employment and decent work for all). The average hourly wage is NGN 1950 (USD 4.47), but this varies widely according to sector and job status. There is a substantial gender pay gap, and women are more likely to be unemployed than men. Underemployment is a significant and more widespread issue than unemployment in Nigeria. On target 8.6 (reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education or training), the NEET rate for 15- to 24-year-olds was 13.4 per cent in 2022. Nigeria faces serious issues under target 8.7 (eradicate forced labour and the worst forms of child labour): recent estimates vary from a third to a half of Nigerian children being involved in child labour, with a third of children out of school. Also of concern is target 8.8 (protect

labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers). Trade unions report that occupational safety regulation and data are poor, and there is a shortage of labour inspectors. Labour rights are systematically violated, with a score of 6.84 (10 being the worst) in 2020. Nigeria has ratified ILO conventions 87 on freedom of association and 98 on collective bargaining.

Much progress is still to be made to achieve target 10.4 (progressively achieve greater equality), although the labour share of GDP increased slightly to 68.2 per cent in 2020. The National Minimum Wage Act came into force in 2019, but a new minimum wage had not been agreed at the time of writing. Social partners are involved in migration policy development in Nigeria under target 10.7 (migration and mobility).

With regard to SDG indicator 13.2 (integrate climate change measures into policies), Nigeria is part of the Climate Action for Jobs initiative supported by the ILO, which brings together representatives from government, employers’ and workers’ organisations, and development partners.

Trade unions report sometimes violent police and government disruption of trade union activity in 2023, indicating that Nigeria is still far from achieving target 16.10 (protect fundamental freedoms).

Similarly, non implementation of agreement reached with Trade Unions across the Country is a major set back in the Nigeria Social dialogue mechanism. There is also an apparent lack of commitment to tripartite by the government is underscored by 2024 Minimum Wage Negotiations. Tripartite meeting were not regular until the Trade unions call for national industrial action, but the new minimum wage is yet to be announced by the federal government. Itbia not worthy that the 2018 minimum wage elapsed on April, 18, 2024.

Another major setback is the increasing shrinking g of democratic space for trade unions to present demands, genuine demands by the trade unions are misconstrued as partisan politics.

Trade unions call on the government of Nigeria to:

• Consider trade unions as major partners, harnessing their democratic membership of large numbers of workers to help deliver the Goals. This should include more capacity building workshops for trade unions, as well as trade union involvement by the Office of the Senior Special Advisor to the President on SDGs, and in the National Planning Commission.

• Support job creation and increase local production through import substitution policy as a key to sustainable economic growth.

• Create pro-poor social protection programmes that provide benefits to households through public or collective arrangements, to protect against low or declining living standards.

• Immediately canvass for a living minimum wage. The current minimum wage of NGN 30,000 is no longer sustainable in a situation of double digit inflation.

• Immediately ratify ILO gender equality Conventions 100 and 111.

• Improve labour standards and protect workers’ rights.

• Promote social dialogue as key to sustainable development, helping to balance competing interests, resolve conflicts, promote tripartism, and positively impact public policy outcomes.

Peru faces multiple challenges stemming from political instability, inflationary pressures, and climate change. Socioeconomic inequality and food insecurity were exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, during which time Peru experienced the highest proportion of deaths worldwide. The Peruvian government is implementing the plan ‘Con Punche Perú’, which focuses on reactivating three main economic axes: families, regions, and sectors. In response to climate emergencies in different regions of the country, the Peruvian government reactivated disaster prevention programmes in coordination with regional and local governments. However, trade union organisations were not involved in dialogue for these plans.

Trade unions report that government policies remain focused on economic growth and attracting international investment, without sufficient concern for human rights at work. Action plans exist to address the labour situation of vulnerable groups, but are not being adequately implemented or monitored. While some human rights actions are implemented with the support of international cooperation, they are often disconnected from medium- and long-term public policy objectives.

The ‘Vision of Peru to 2050’ is the basis for a Strategic Plan for National Development (PEDN), which specifies how the four national objectives and specific indicators relate to SDGs. Apart from this, while SDGs are mentioned in some specific policy areas, such as national plans on human rights, they are not systematically integrated across all policies. Human rights policies do not receive extra funding.

There is an overall lack of monitoring mechanisms related to the implementation of the 2030 Agenda. The Peruvian state has no public budget to monitor SDG implementation, or systems to verify public spending on their implementation. The National Institute of Statistics (INEI) does not have an ongoing monitoring program and only prepares caseby-case reports at the request of public entities.

No access to information at all

Trade union activity is restricted by anti-union policies and the informalisation of the economy. Multi-stakeholder dialogue is the exception rather than the rule. Trade unions attribute this to the ongoing crises, as well as high levels of corruption and technical and professional deficiencies at all levels of government. Limited dialogue does take place for the implementation of national human rights policy, including the National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights. Trade unions have had a few specific exchanges with the UN Resident Coordinator for Peru. They also provide input to a civil society-led working group for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda.

There are information sessions, but no interaction

The national government does not involve the social partners in the definition and implementation of a national SDG plan

Peru has a high level of human development with an index (HDI) of 0.762, but challenges remain. With regards to SDG target 1.1 (extreme poverty), while the proportion of the population living below the international poverty line decreased from pandemic levels to 3.78 per cent in 2023, 27.5 per cent of the population were living below the national poverty line in 2022. On target 1.3 (nationally appropriate social protection systems), in 2020, only 29.3 per cent of the population was covered by at least one social protection system. There are significant regional disparities in access to essential services (target 1.a.2). In 2022, 95 per cent of the population had access to basic drinking water and 78.5 per cent to basic sanitation services. In 2021 the proportion of total government spending on essential education services increased to 17.9 per cent.

Peru is making some progress on target 5.5 (women’s full and effective participation). The ratio of female to male labour force participation was 84.4 per cent in 2022 and the percentage of seats held by women in national parliament increased to 39 per cent in 2023. In 2021, Peru reported that gender budgeting tools still need to be fully integrated into the budget cycle.

Much remains to be done to implement target 8.3 (support decent job creation) as informality remains high: the share of informal employment in the non-agricultural sector was 71.4 per cent in 2021. Trade unions attribute this to a drop in GDP and lack of social spending by the government. For target 8.5 (full and productive employment and decent work for all), the total unemployment rate was 5.2 per cent in 2022 and the gender pay gap stood at 5.7 per cent in 2021. Indicators for target 8.6 (reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education or training) stood at a high 22.8 per cent in 2022, with women (25.8 per cent) being more affected than men (19.9 per cent). While Peru has policy measures in place to address target 8.7 (eradicate forced labour and the worst forms of child labour), child labour remains an issue, particularly in the agriculture, fishing and mining sectors, involving 12.2 per cent of children (11.3 per cent of girls) in 2020. On target 8.8 (protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments

for all workers), there are data gaps for occupational injury rates and numbers of trained labour inspectors. Fundamental labour rights are not yet guaranteed effectively: in 2021 the level of national compliance with labour rights (freedom of association and collective bargaining) stood at 4.2 out of 10. Trade unions report that implementing the national plan for Business and Human Rights has slowed in the past two years, with many targets not being met. Peru has ratified ILO Conventions No. 87 on freedom of association and No. 98 on the right to organise and collective bargaining.

Inequality remains high in Peru. There is still much to be done to achieve target 10.4 (progressively achieve greater equality): in 2020 the labour income share as a percentage of GDP was 45.2 per cent; with 32.9 per cent of total GDP going to the top 10 per cent of income earners versus only 4.8 per cent of GDP for the bottom 20 per cent of earners. Migration laws and policies are in place but more could be done to ensure migrants’ inclusion in society under target 10.7 (migration and mobility). While many young Peruvians still emigrate, Peru has recently seen an increase in immigrants, mostly from Venezuela.

Peru has recently experienced more frequent and extreme weather events. Under target 13.2 (integrate climate change measures into policies), the country has improved its institutional environmental framework to meet Paris Agreement commitments and a long-term strategy for the green transition is being developed. Further efforts are required however, including on renewable energy, reversing deforestation, and environmental pollution.

The situation is worsening with regard to target 16.10 (protect fundamental freedoms). In 2023 Peru was deemed to have systematic violations of rights under the Global Rights Index and its press freedom score had declined to 52.74 out of 100.

Trade unions call on the Peruvian government to:

• Strengthen social dialogue and incorporate a human rights approach to public policies. Specifically, establish an appropriate consultation mechanism within the National Council for Labour and Employment Promotion (CNTPE).

• Provide a budget, appropriate tools and competencies to monitor implementation of SDGs and the national Business and Human Rights Plan.

• Create decent jobs by diversifying productivity, taking into account the climate and environmental crisis. Implement vocational training policies and ratify ILO Conventions No. 155 on occupational health and safety and No. 158 on termination of employment.

• Ensure social protection by implementing robust social protection floors in accordance with ILO Convention No. 102. Increase health and pension coverage for the most vulnerable groups and put in place unemployment insurance: ratify ILO Conventions No. 168 and part IV of Convention No. 102.

• Put in place minimum living wages, ratifying ILO Convention No. 131 on the fixing of minimum wages. Promote collective bargaining.

• Promote workplace equality with the participation of companies and civil society including trade unions. Establish equal pay and work-life balance policies; and care centres.

• Secure labour rights by implementing all ratified ILO Conventions and addressing the recommendations made by ILO Control Bodies. Strengthen the Labour Administrative Authority and ratify ILO Convention No. 150. Strengthen the labour inspection system and justice bodies.

#HLPF2024

The South African government has implemented various programmes to address the ongoing multiple crises. In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the government worked closely with trade unions and businesses to address occupational health and safety, provide subsidies compensating workers for lost wages and support businesses in retaining employees.

To address the food crisis, the South African government has put in place a basic social security grant enabling nearly half of the population of the country, including 8 million unemployed persons, to buy food. However, by 2025, around half of the population is projected to be struggling from food insecurity and hunger, suggesting more long-term actions will be necessary.

A Just Energy Transition Investment Plan is being put in place to enable the country to move from carbon intensive to cleaner forms of energy generation – initial efforts will focus on moving away from coal and supporting impacted coal workers, investments in new energy vehicles and green hydrogen. In October 2023, the National Assembly approved a Climate Change Bill, which if approved by the National Council of Provinces and the President, would legally bind the country to reduce its emissions.

While South Africa has no designated SDG plan as such, it has integrated the objectives of the 2030 Agenda into individual government departments’ annual plans and the country’s budget. Each government entity – both ministries and municipalities – are responsible for the implementation of their sectoral objectives in this regard. Overall, trade unions report that sufficient resources have been allocated to the implementation of the 2030 Agenda, but challenges remain in connection to raising the tax revenue needed to fund the country’s development. Trade unions report that there has been an improvement in the implementation of the SDGs in South Africa, as the government has accelerated its fight against corruption at the level of local governments and state-owned enterprises – seen as one of the main impediments to development. Trade unions also welcome measures such as the passing by the parliament of a National Health Insurance Bill

laying the foundation for universal health care, and the pending pension reforms and transformation of the unemployment grant into a universal basic income grant, which are set to advance the implementation of the SDGs. Transparency on decision making, including on the implementation of the SDGs, is mandated by South Africa’s constitution. Trade unions suggest that the government provides accurate information in this regard, although this could at times be more extensive. The National Economic Development and Labour Council (Nedlac) is consulted on the government’s development policy, with discussions covering both SDG 8 and other goals. Trade unions also participate in parliamentary hearings. Trade unions report that their input is, in most instances, taken on board by the government.

Regular access to limited information

There is a structured consultation/ multi-stakeholder platform

There are tripartite instances to implement and monitor the SDGs involving