Storytelling in the Great Outdoors:

How can the emerging field of adventure photography develop its own identity?

Izzy Wedderburn

Storytelling in the great outdoors: How can the emerging field of adventure photography develop its own identity?

BA Graphic Design Dissertation

by Izzy Wedderburn

University for the Creative Arts

November 2023

Research

Title

List of Illustrations (8) Acknowledgements (11) Introduction (13)

Chapter Two: Theories & Ideas within Adventure Photography (29) Contents

Chapter One: Defining Adventure Photography (17)

Adventure

Chapter Three: The Evolution of

Photography (39)

Adventure

Chapter Four: The Future of

Photography (53) Conclusion (61) Appendices (65) Bibliography (107) Contents

Figure 1

List of Illustrations

Wedderburn, I. (2023) Spider diagram highlighting the key components which make up an adventure photograph. [Diagram]

Figure 2

Wedderburn, I. (2023) Radar diagram showing where adventure photography intersects with other photographic practices. [Diagram]

Figure 3

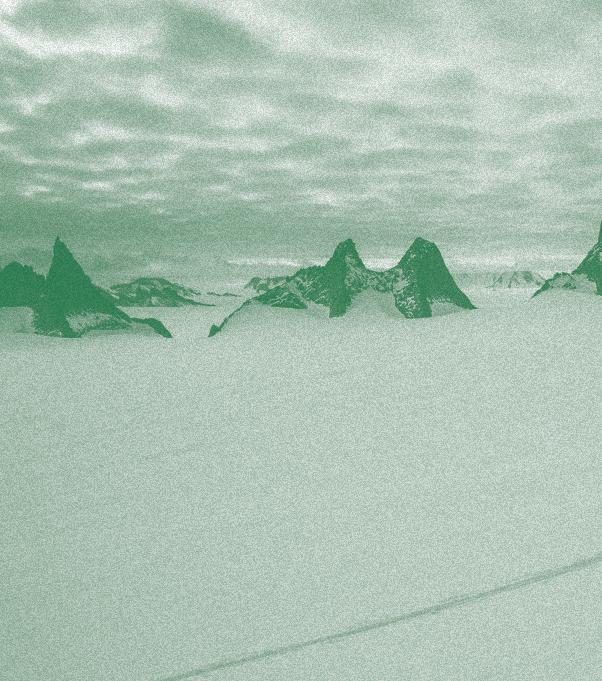

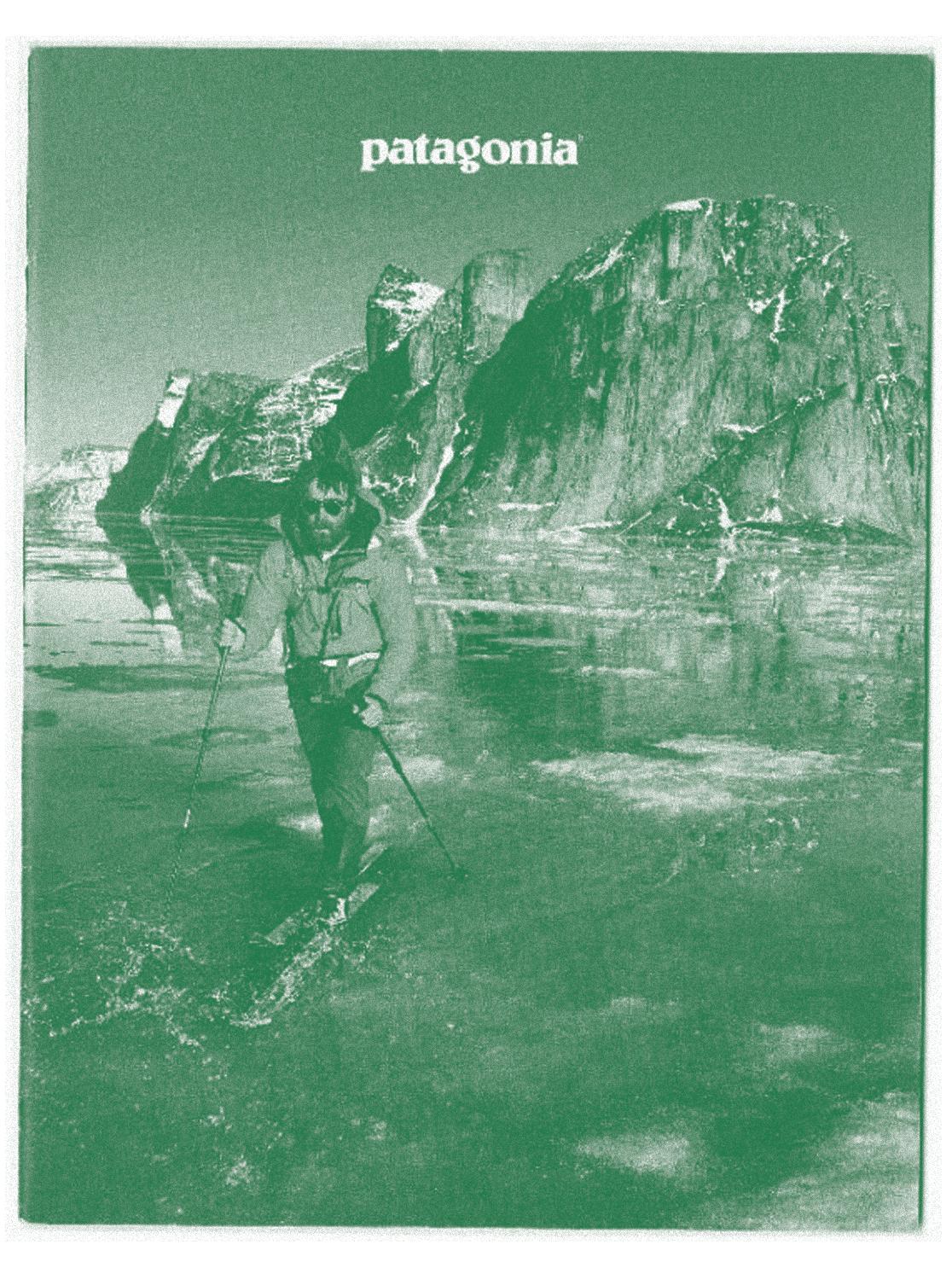

Chin, J. (2013) Conrad Anker, Queen Maud Land, Antarctica. [Photograph] At: https://jimmychin.com/stills (Accessed 20/09/2023).

Figure 4

Wedderburn, I. (2023) Types of adventure photography. [Diagram]

Figure 5

Vernet, C. J. (1772) A Shipwreck in Stormy Seas. [Oil on canvas] At: https://www.nationalgallery.org. uk/paintings/claude-joseph-vernet-ashipwreck-in-stormy-seas (Accessed 03/10/2023).

Figure 6

Ozturk, R. (2023) Alex Honnold and Tommy Caldwell on the top of Devil’s Thumb, Alaska. [Photograph] At: https://www.instagram.com/ renan_ozturk/?img_index=1 (Accessed 03/10/2023).

Figure 7

Gilpin, W. (1809) Distant view of Rhyddland Castle, Wales. [Print] At: https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/ art-artists/work-of-art/distant-viewof-rhyddland-castle (Accessed 04/10/2023).

Figure 8

insta_repeat (2023) Must be some really good pavement. [Instagram, screenshot] At: https://www.instagram.com/p/Cpv1G08JL4j/ (Accessed 08/11/2023).

Figure 9

Ruderman, E. (2022) Switzerland. [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Canterbury.

Figure 10

Hurley, F. (1915) Endurance in Full Sail, in the Ice (side view). [Photograph] At: Royal Geographical Society, London.

Figure 11

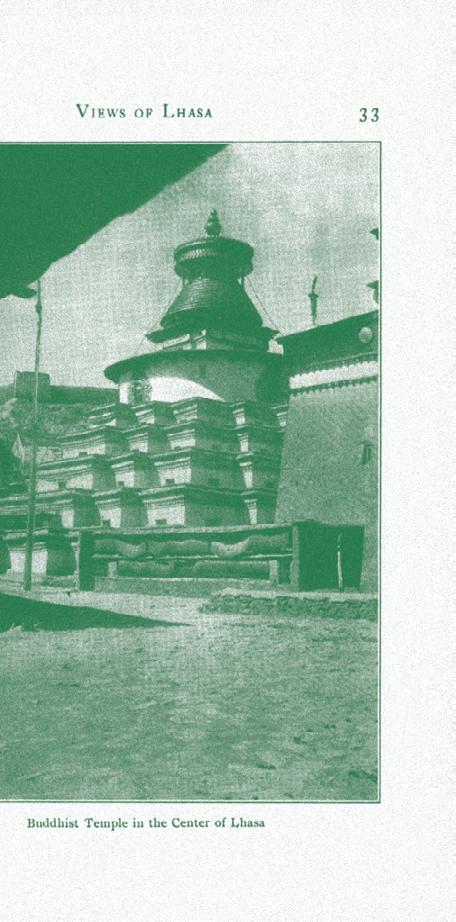

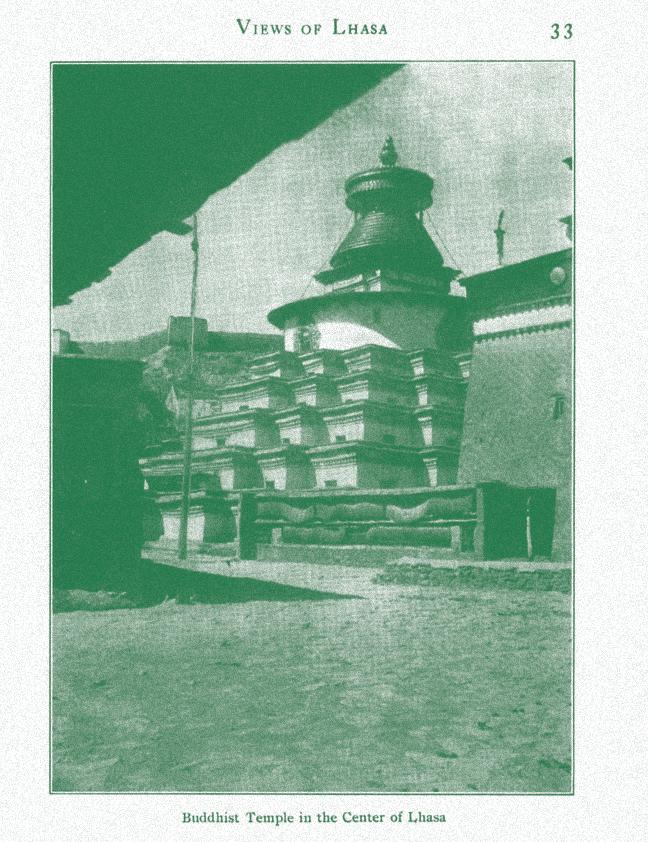

National Geographic (1905) Views of Lhasa, Tibet. [Photograph] At: https://www.newtonplks. org/2020/04/access-132-years-of-national-geographic-magazine/ (Accessed 21/09/2023).

Figure 12

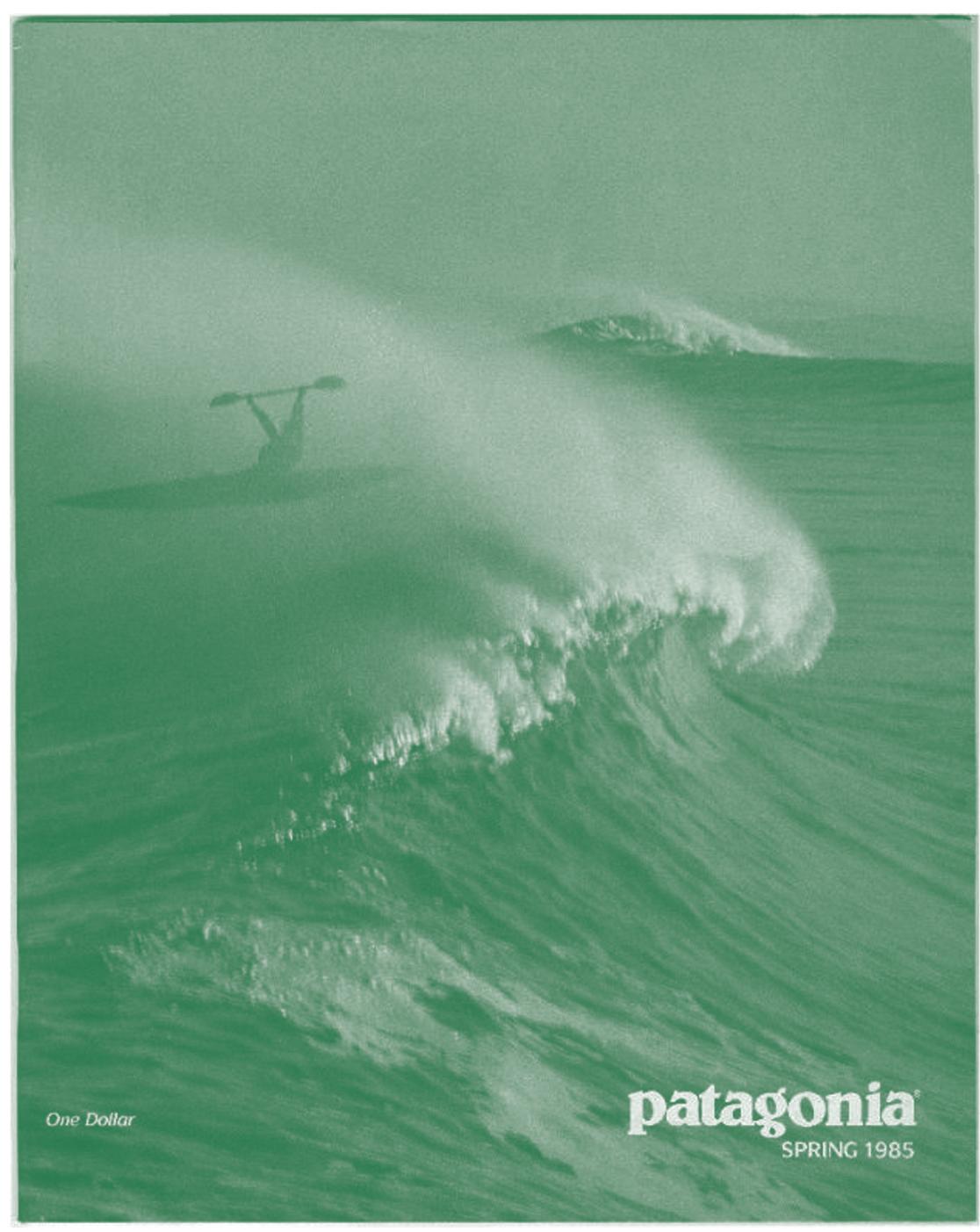

Patagonia (1985) Patagonia Clothing Catalogue Spring Cover. [Catalogue] At: http://exhibits.lib.usu.edu/ exhibits/show/outdoorcatalogs_o-z/ company_gallery/patagonia (Accessed 27/09/2023).

Figure 13

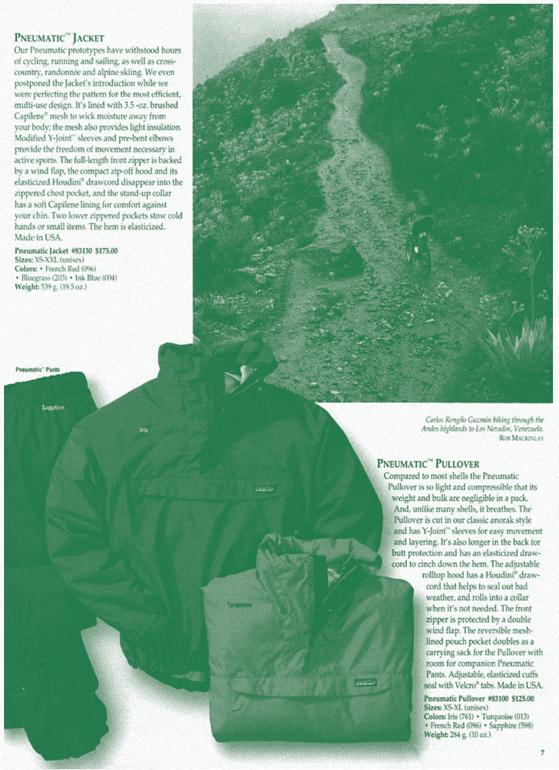

Patagonia (1993) Patagonia Peumatic Pullover advert. [Catalogue] At: http://www.outdoorinov8.com/patagoniaimages.html (Accessed 08/10/2023).

Figure 14

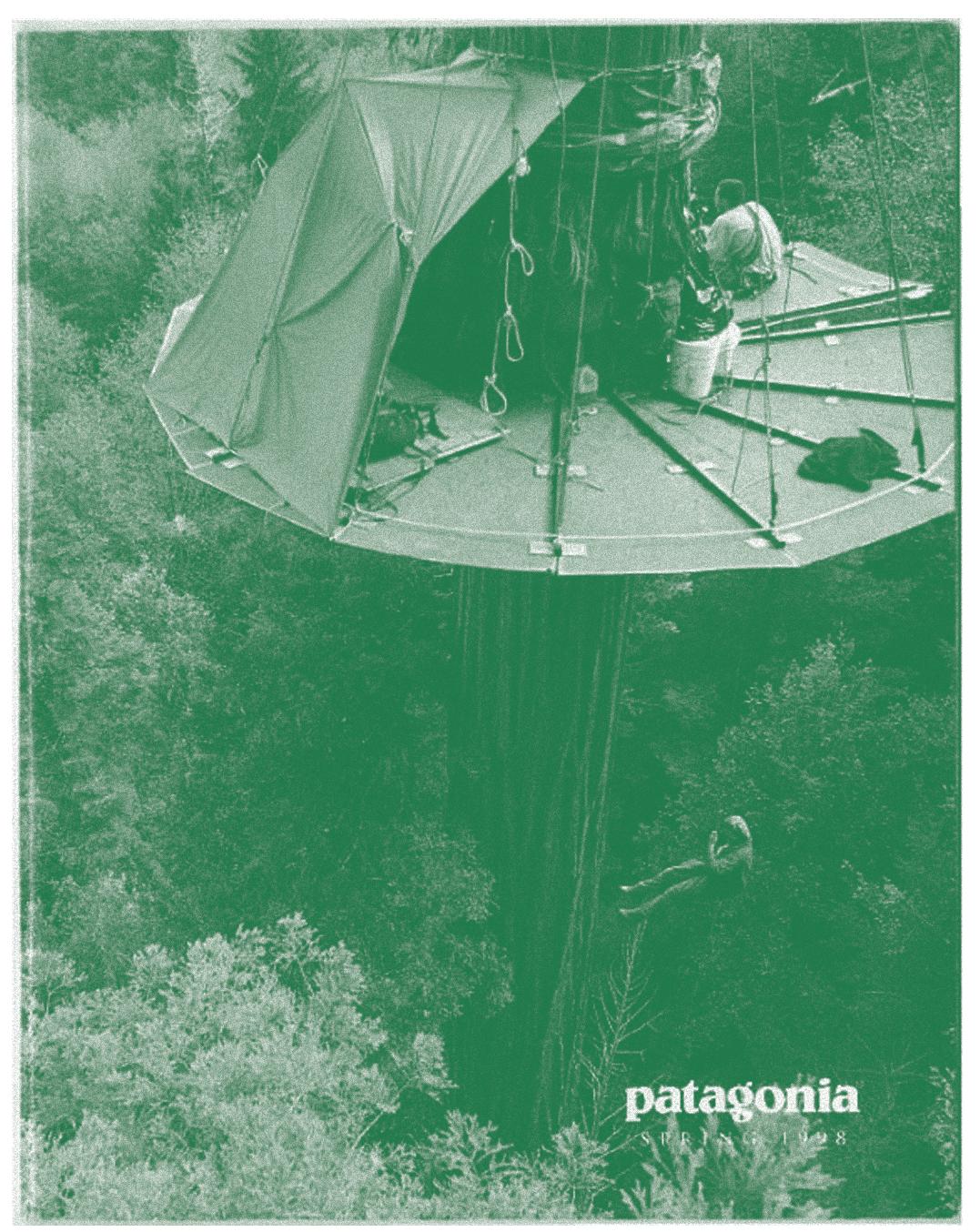

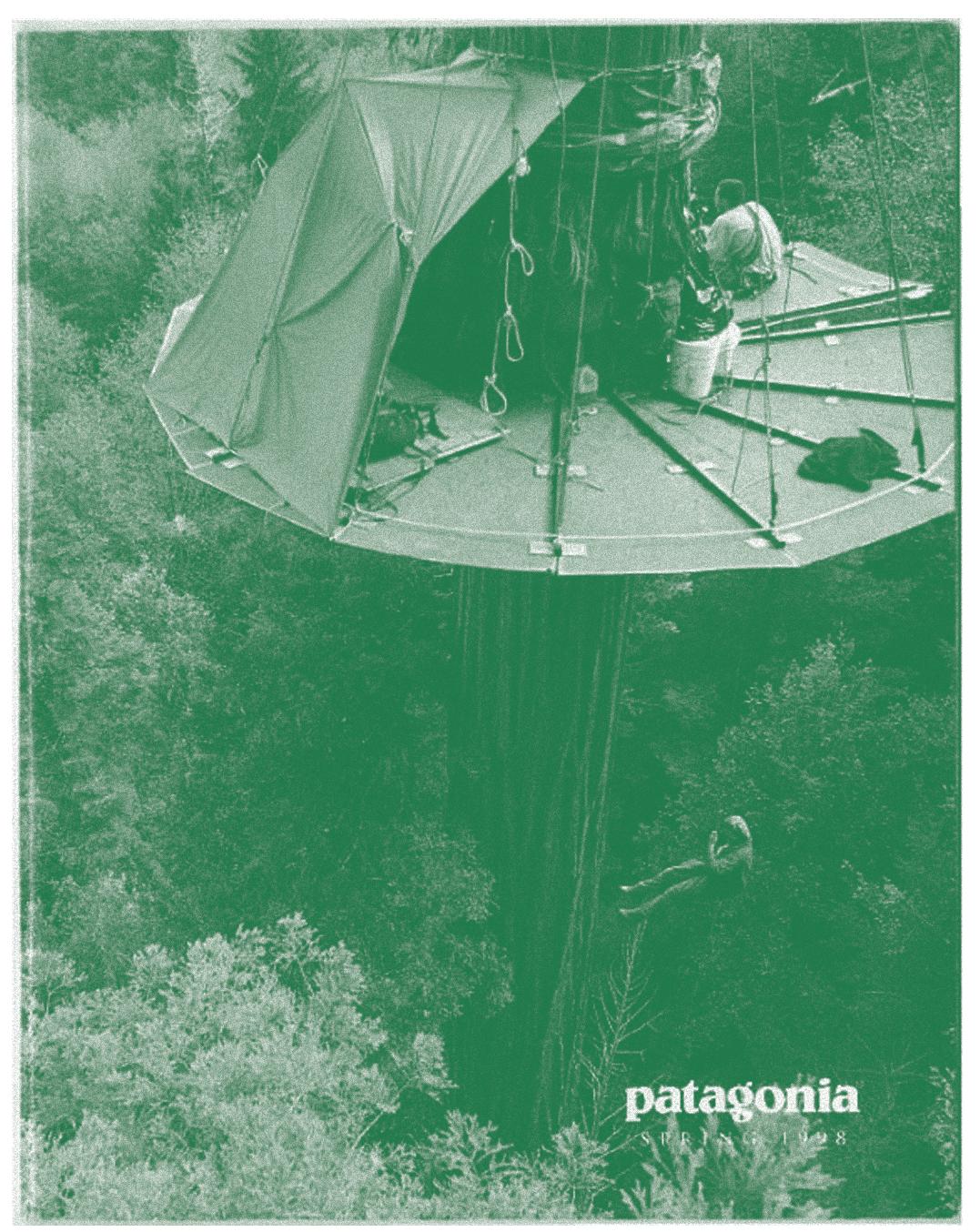

Patagonia (1998) Patagonia Clothing Catalogue Spring Cover. [Catalogue] At: http://exhibits.lib.usu.edu/ exhibits/show/outdoorcatalogs_o-z/ company_gallery/patagonia (Accessed 27/09/2023).

8

Figure 15

List of Illustrations

Patagonia (2018) Patagonia Clothing Catalogue Winter Cover. [Catalogue] At: http://exhibits.lib.usu.edu/ exhibits/show/outdoorcatalogs_o-z/ item/24391 (Accessed 27/09/2023).

Figure 16

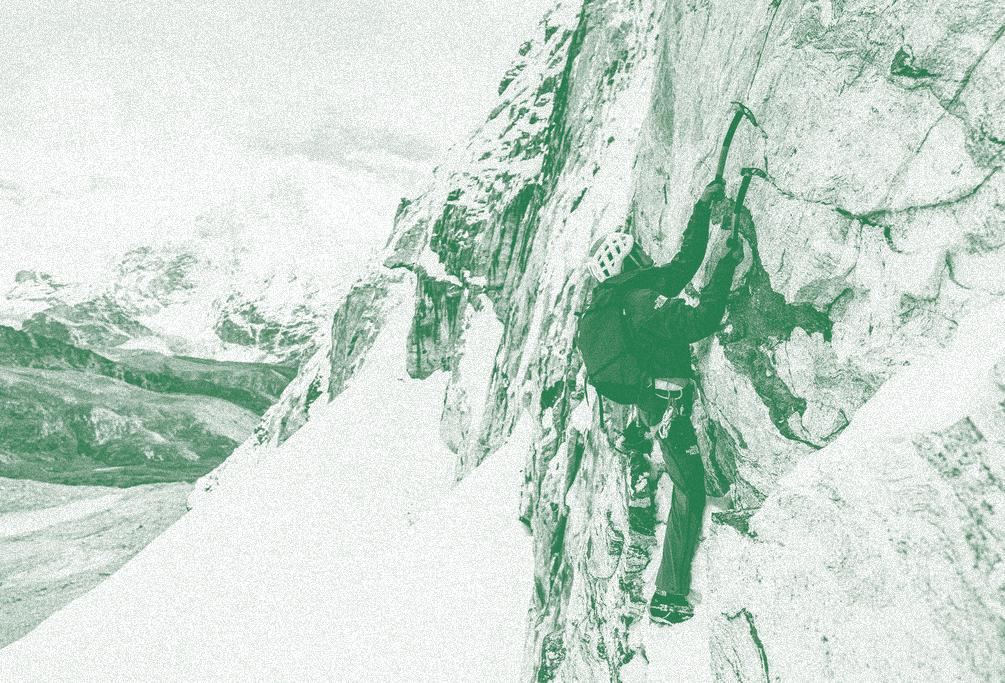

Dumas, M. (2022) Alpine Climber. [Photograph] At: https://outdoorsmagic.com/article/the-north-face-advanced-mountain-kit-review/ (Accessed 21/09/2023)

Figure 17

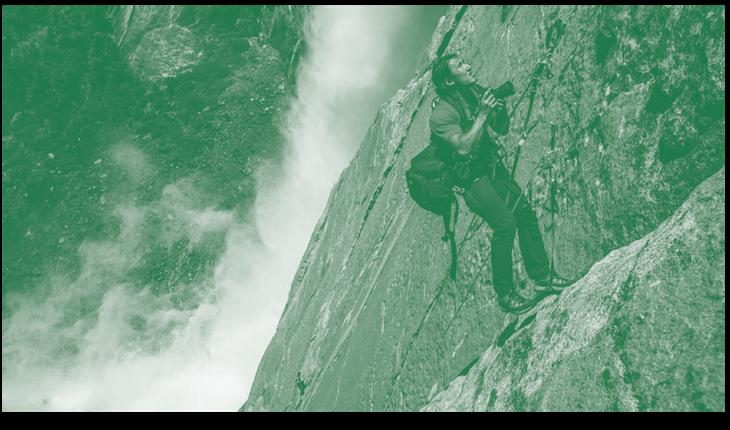

Schaefer, M. (2018) Jimmy Chin hangs off a line near Yosemite Falls as he photographs climbers on the Freestone route. [Photograph] At: https://www. nationalgeographic.com/adventure/ article/interview-photographer-climber-jimmy-chin-master-art-of-chill (Accessed 09/11/2023).

Figure 18

Wedderburn, I. (2023) Spider diagram highlighting the key components which make up an adventure photograph. [Diagram] (repeated diagram)

Figure 19

Wedderburn, I. (2023) Hiking in the Swiss Alps. [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Canterbury.

Figure 20

Burtynsky, E. (2016) Deforestation on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. [Photograph] At: https://www. edwardburtynsky.com/projects/photographs/anthropocene (Accessed 29/09/2023).

Figure 21

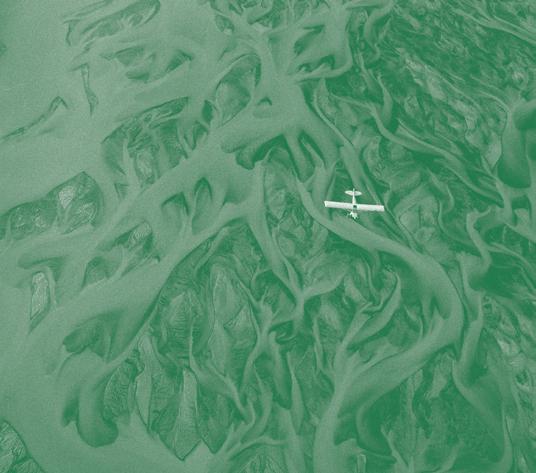

Burkard, C. (2021) Arial photograph of Iceland’s river system. [Photograph] At: https:// alphauniverse.com/stories/ chris-burkard-on-conservationphotography-and-his-creative-drive-an-earth-day-conversation/ (Accessed 29/09/2023).

Figure 22

Watkins, C. (1861) The Yosemite Valley from “Best Central View” [Photograph] At: https://www. carletonwatkins.org/getviewbyid. php?id=1001341 (Accessed 29/09/23)

Figure 23

Adams, A. (1937) Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite National Park. [Photograph] At: https://www.bbc.com/ culture/article/20230706-ansel-adamseight-of-the-most-iconic-photos-ofthe-american-west (Accessed 29/09/2023).

9

Acknowledgments

I would like to say a big thank you to my interviewees; Evan Ruderman, Alex Roddie, John Summerton and Matt Pycroft for kindly taking the time out of your busy lives to chat to me on all things adventure photography. This research would not have been possible without your collective knowledge and expertise. Also, thank you to my supervisor Sara Andersdotter for your academic support, feedback and positive enthusiasm for this project. It has definitely been an adventure!

Izzy Wedderburn November 2023

11

Introduction

13

Introduction

The aim of this research is to explore the emerging field of adventure photography; discussing what it is, where it has originated from, and how it is developing into a new photographic practice with its own identity. The motivation comes from my passion for photography, love of the outdoors, and my creative practice within editorial design. Recently, I have started to photograph my own adventures; the camera has become a tool for curiosity when venturing into new, unusual, or exciting environments.

In March 2023, I attended a talk in London, where British adventure photographer Matt Pycroft interviewed American adventure photographer Chris Burkard. I was immensely inspired and came away keen to understand more about what they do. I quickly realised that there is a limited amount of academic research available on adventure photography. Therefore, this research is situated as a significant contribution to photographic literature, as it uncovers, identifies and explains a new, emerging practice.

In order to answer my research question, I employed a variety of different research methods. Firstly, using qualitative methodology I conducted long form online interviews with three professionals within the field. I began by interviewing American adventure photographer Evan Ruderman, who for the past three years has been a photography assistant to the renowned adventure photographer Chris Burkard, working across global expeditions and commercial projects. I then contacted Sidetracked, a British adventure publication which focuses on telling meaningful stories of adventure and exploration from all around the world. I interviewed Alex Roddie, the chief editor, and John Summerton, the creative director and head graphic designer for the magazine. Lastly, I interviewed Matt Pycroft, a British expedition filmmaker, photographer, and creative director of the production company Coldhouse Collective, who also works for the National Geographic, is a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, and runs a popular podcast.

I also attended a variety of events which included the Banff Mountain Film Festival, Sidetracked Live, exhibitions at the Royal Geographical Society, as well as listening to podcasts such as the Adventure Podcast. Alongside primary research, I undertook a variety of secondary research; investigating philosophies, contexts, case studies, and learning key ideas within photographic theory from academic journals, news sources, scholarly books, documentary films, and photography readers,

14

Introduction

to gain a deeper understanding of the field of adventure photography. The text is structured into four chapters, beginning by defining adventure photography. I achieve this by analysing definitions from my interviewees, and developing my own diagrams to facilitate the understanding of what adventure photography is, where it intersects with other photographic practices, and to highlight the range of adventure photography. I then discuss the importance of authenticity within adventure photography, drawing on the likes of key photographic theorists; David Bate and Liz Wells. The second chapter explores the significant ideas and theories seen within the practice by discussing the concept of the sublime, analysing the ideas of philosophers Edmund Burke, Immanuel Kant, and art historian Simon Morley. The chapter then goes on to investigate William Gilpin’s concept of the picturesque, the significance of snapshot photography, and micro adventures. The third chapter tries to uncover the origins of adventure photography, looking at military expeditions, and key publications such as the National Geographic and Patagonia clothing catalogues. The fourth final chapter, discusses the future of adventure photography; critiquing the issues it faces with diversification and sustainability, and how it can be used as a tool for environmental awareness.

15

Chapter One: Defining Adventure Photography (1.1)

Existing Definitions (1.2)

Identifying Adventure Photographs (1.3)

Range of Adventure Photography (1.4)

Authenticity & Documentary

17

Chapter One

The aim of this chapter is to map out what adventure photography is, through analysing definitions from key practitioners within the field, discussing where it intersects with other photographic practices, and looking at what constitutes an adventure photograph, illustrated through my own diagrams. It will also highlight the range of adventure photography, and the important relationship between adventure photography and authenticity.

Existing Definitions

Drawing upon my interviews, Alex Roddie, adventurer and chief editor of Sidetracked magazine believes adventure photography is about “storytelling: conveying character-led moments in a narrative through strong, simple composition, as well as immersing the viewer in the setting” (2023). Roddie’s definition highlights the significance of storytelling and narrative, which can be seen in many forms of photography, such as documentary, travel or snapshot. By highlighting “character-led moments” suggests there is a key person driving the story, who the viewer is following on their journey. He also signifies the importance of the environment where the story is taking place.

According to the British expedition photographer Matt Pycroft, adventure photography is about “documenting communities, cultures, environments, and journeys, which are not native to yourself” (2023). Pycroft’s definition could almost be seen as a description of documentary photography, more than adventure photography, although, highlighting “environments and journeys” connects more closely with the notion of adventure. He also mentions that what the photographer is documenting is not native to oneself, suggesting both an unknown environment, and a personability to adventure photography. Pycroft went on to say that he has a resistance to the term as it is very difficult to describe, and can mean many things to many different people (2023).

Adventure photographer Evan Ruderman believes adventure photography is “the art of documenting exploration” and “shooting things as they happen” (2023). This definition is more specific than the others. Documenting exploration suggests going into an unknown area or place for the first time, which is similar to Pycroft’s point on documenting in environments which are not known to the photographer. “Shooting things as

19

they happen” shows an immediacy and authenticity to the photographs, suggesting they haven’t been overly staged or premeditated. He also stressed the broad nature of the term which means many things to many people. However, as I will discuss next, I have developed some key parameters which help unpack the identity of an adventure photograph.

Identifying Adventure Photographs

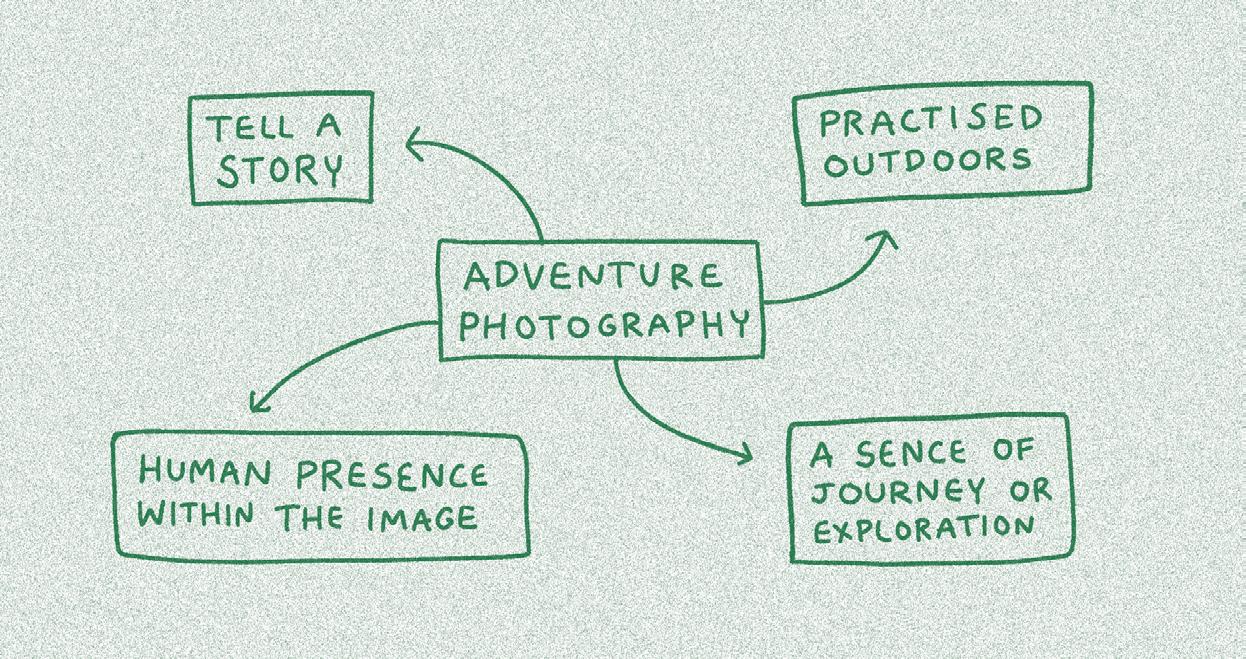

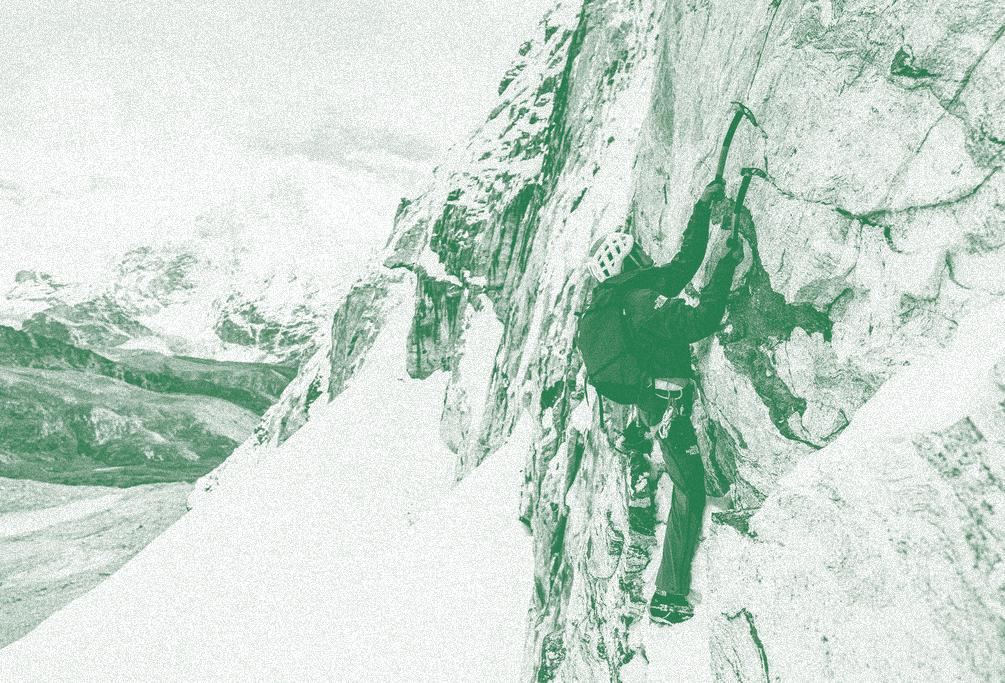

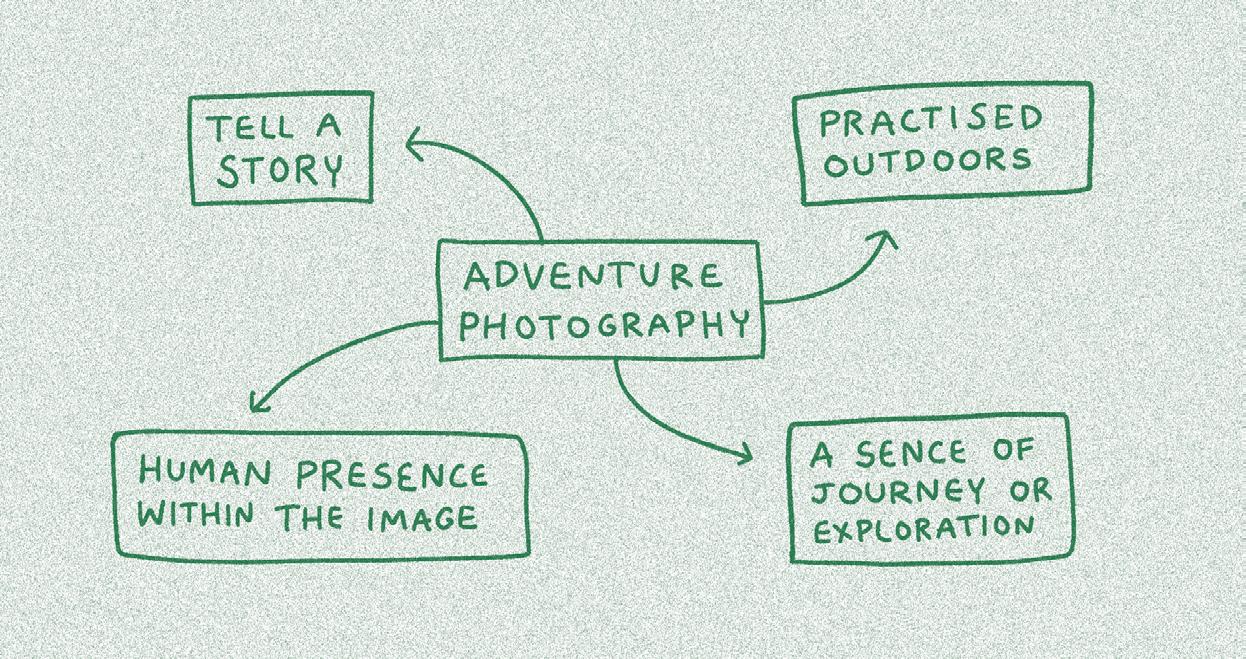

To visualise the different elements that make up adventure photography, I created two diagrams. My first diagram (figure 1) illustrates the key components of an adventure photograph. Firstly, the photograph must be captured outdoors, whether up a mountain, or in a local forest. Secondly, there has to be a sense of journey, a drive of exploration into a new environment (physical journey), and/or where one is pushing oneself out of their comfort zone (emotional journey). Thirdly, there has to be a narrative or story, either on a personal level or with the motif to inspire and share to others. Finally, the most significant point, is the human presence within the

20

Chapter One

Figure 1. Wedderburn, I. (2023) Spider diagram highlighting the key components which make up an adventure photograph [Diagram]

Defining Adventure Photography

2. Wedderburn, I. (2023) Radar diagram showing where adventure photography intersects with other photographic practices. 0 = does not intersect with practice, 5 = complete overlap with practice [Diagram]

image, be it an actual present human, or the interaction or evidence of one. Therefore, adventure photography can be defined as the documentation of human focused, meaningful stories, in the great outdoors, with a strong emphasis on the journey.

My second diagram (figure 2) shows where adventure photography intersects with other photographic practices. As illustrated, adventure photography is interdisciplinary, combining elements of landscape, fine art, documentary, extreme sports and snapshot photography. It’s important to highlight this as adventure photography can be seen within many different practices, and still be classed as an adventure photograph due to the key components (figure 1) which make up the image.

Figure 3 illustrates a textbook adventure photograph, showcasing adventurer Conrad Anker ski touring on an expedition in Antarctica. Remove the human and manmade ski line cut into the snow, and the identity of the image changes into a landscape or fine art composition. There is also a level of imagination, actively involving the viewer into the

21

Figure

Chapter One

22

Defining Adventure Photography

23

Figure 3. Chin, J. (2017) Conrad Anker, Queen Maud Land, Antarctica [Photograph]

Chapter One

image, where Anker’s presence creates a narrative, a journey, a story, in an unknown environment, which is key to the notion of adventure photography. However, as I will discuss next, adventure photography is not just limited to faraway places on extreme expeditions, adventure photography can be in your local back yard (Ruderman, 2023).

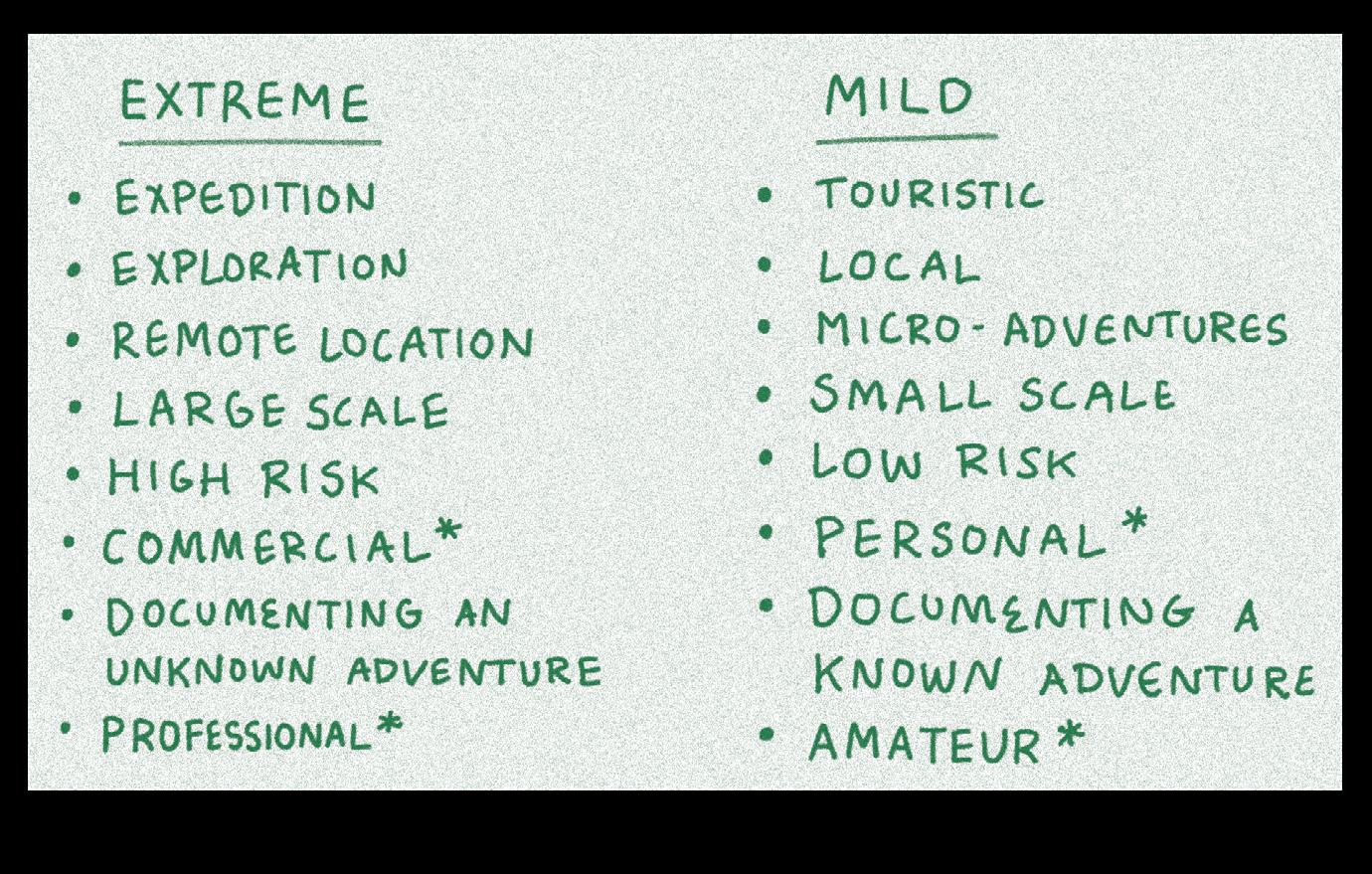

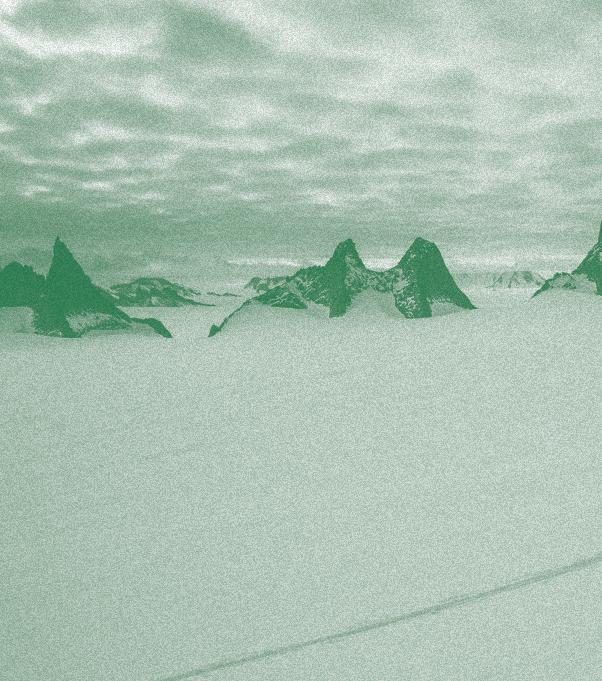

Types of Adventure Photography

Within any practice there is a spectrum or hierarchy, which is also true for adventure photography. To help visualise this I created a list (figure 4) which illustrates the range of adventure photography.

‘Extreme’ can be defined as expedition and exploration style adventure photography; documenting new adventures, which are often high risk due to being on a large scale, in remote locations, such as documenting a multiday ski expedition to the North Pole. For these reasons, extreme adventure photography is significantly more commercial because of the higher cost, scale and duration of these types of adventures. At the other end of

24

Figure 4. Wedderburn, I (2023) Range of adventure photography [Diagram]

Defining Adventure Photography

the spectrum is ‘mild’, which is more touristic adventure photography; documenting adventures which may have been documented before, that are often low risk due to being on a smaller scale, in more local locations, such as documenting a single day kayaking trip in a local National Park. For these reasons, mild adventure photography is significantly more personal because of the lower cost, scale and duration of these types of adventures. However, this list is problematic, as highlighted with the asterisk*. A professional, someone who makes an income from adventure photography, can practice elements of ‘mild’ adventure photography, and an amateur, someone who practices adventure photography as a pastime, can practice elements of ‘extreme’ adventure photography; they are not mutually exclusive. The same goes for commercial and personal; ‘mild’ adventure photography can be commercial, and ‘extreme’ can be personal. Therefore, this list only acts as a framework to distinguish the range of adventure photography in its idealised form.

Authenticity and Documentary

Documentary photography is the most significant practice within adventure photography, as demonstrated in the three definitions by professionals, and my diagrams. According to Derick Price, a key writer on photography, documentary has “a special relationship to real life and a singular status with regard to notions of truth and authenticity” (2019:70). Price is highlighting the important connection between documentary with reality and authenticity. The idea that photographs are indexical; providing “tangible evidence” of what we are seeing does exist, or once existed (Wells, 2009:348).

However, according to the acclaimed American writer on photography Susan Sontag, the camera is not a “copying machine” of reality, and photographs are not facts (2019:87). Moreover, the camera cannot operate without human intervention (Sontag, 2019:88). Every photographer decides what goes into the frame and what does not, and more so with professionals; what to set the aperture to, the shutter speed, the ISO (MoMA, 2023). Sontag goes on to say that the camera works by the “cropping of reality” (2019:122). Much like framing, cropping is about choosing what to include and what to crop out, which highlights this conscious bias. It also shows the viewer that what is within the frame is “something worth seeing”

25

(Sontag, 2019:11), as this image has been specifically taken, therefore holding value. This is especially true in adventure photography, where there is a meaningful story worth sharing, which the photographer sees as transformative and important.

For professional adventure photographers, especially when documenting something meaningful and of value, it is important for the camera-person to get the truest representation of the event. This enables the audience the best understanding of the real-time events unfolding, and having a ‘human presence’ within the image gives the image significant authenticity. This can involve visually organising the events in front of the camera, which can rely on many different viewpoints and camera angles; using drones, tripods, or helicopters. Pycroft reiterates this point in his practice by saying the “method of my taking that photograph does not alter the image” (2023), highlighting that the way he takes the photograph does not change the authenticity of the image. Creative director of Sidetracked magazine, John Summerton, believes it’s the “raw and unfiltered” moments which portray the “highs and lows of the journey” (2023), that add to the depth and realism of the storytelling, which enables the production of strong adventure photographs.

To summarise, this chapter concluded, through analysing definitions from practitioners and the development of my own diagrams, the existence of adventure photography, but also the huge lack of understanding and mutual acceptance on the identity of the practice. The chapter also discussed the importance of authenticity and reality in adventure photography, due to its close relationship with documentary photography. In order to understand the foundations of adventure photography, the next chapter will explore the key ideas and theories seen within the practice.

26

Chapter One

Chapter Two: Theories & Ideas within Adventure Photography

(2.1) The Sublime (2.2)

The Picturesque (2.3) Snapshot Photography, & the Snapshot Aesthetic (2.4) Micro Adventures

29

Chapter Two

This chapter will explore the key theories and ideas seen within adventure photography, which include the concept of the sublime, the picturesque, snapshot photography and the snapshot aesthetic, as well as the idea of micro-adventures.

The Sublime

Key to adventure photography is the concept of the sublime. According to the famous Irish philosopher Edmund Burke, the sublime is the “strongest emotion the mind is capable of feeling” (1998:36). Burke’s 18th century concept connects the idea of sublimity with experiences provoked within nature, due to its “grandeur”, “vastness” or “obscurity” (1998). He is suggesting that such intense landscapes or natural phenomena are so grand, powerful, and incomprehensible to the eye of humankind, that they can fill us with fright and terror. German philosopher Immanuel Kant then expanded on this idea of sublimity and the mind, called the sublime experience, where he believed sublimity is an attribute of the mind and not of nature (1973:232). The emotional impact from a dramatic landscape on oneself is what causes sublimity, more so than the dramatic landscape itself. In the 18th century many British painters depicted scenes of the sublime in their work as seen by French landscape painter Claude-Joseph Vernet (figure 5). The painting holds huge violence; large crashing waves, fork lighting, heavy winds, a ship about to wreck, with bodies suffering against the tide, highlighting the fury and force of nature, against humankind (Bate, 2029:116).

Fast forward to 2023, the sublime can be seen within adventure photography. Figure 6 is an image of a very recent first ascent of the Devil’s Thumb in Alaska, taken by National Geographic photographer Renan Ozturk (McLemore, 2023). The image captures Burke’s spirit of the sublime; the huge slab of rock, in the shape of a thumb, has a significant power to it, projecting up through the mountains, living up to the name of ‘devil’, showing the strength and grandeur of nature. However, art historian Simon Morley’s idea of the sublimeas a mix of fear and delight (2021), is even more true in this image. If you look closely there are two climbers standing on top of the tip of the thumb, highlighting the magnificence of both nature and of humankind.

31

Figure 5. Vernet, C. J. (1772) A Shipwreck in Stormy Seas [Oil on canvas]

Chapter Two

32

Figure 6. Ozturk, R. (2023) Alex Honnold and Tommy Caldwell on the summit of Devil’s Thumb, Alaska [Photograph]

Theories & Ideas within Adventure Photography

Extreme adventure photography can often attract high sensation seekers, hunting out “highly stimulating and emotionally charged environments” (Carter, 2019:4). This can be seen both in their practice, to show the untameable force of nature against man (Wells, 2009:351), but also for the personal psychological experience of “terror-tinged thrill” (Morley, 2021) from the adventure itself.

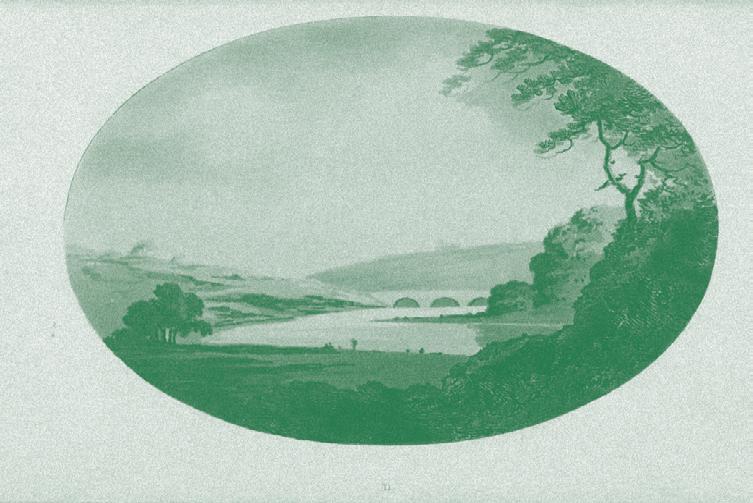

The Picturesque

Another concept which is key to adventure photography is the picturesque. First popularised in 18th century Britain, by William Gilpin, writer, clergyman and printmaker (RA, s.d.), the picturesque means a kind of beauty which is “agreeable in a picture” (Gilpin, 1792), that represents nature in an “idealised” form (Thompson, s.d.). Gilpin published a series of guides which showed picturesque scenes from around the British Isles, highlighting the natural beauty of its landscapes, and quaint pastoral views (Thompson, s.d.). He had a significant part to play in initiating this “picturesque tourism”, where people of middle classes began wanting to visit these printed scenes to experience them for themselves (Alexander, 2015:65).

Figure 7 is a landscape print by Gilpin, where there is a sense that the image has been curated so the viewer can appreciate the beauty of the landscape (Bate, 2019:116), whilst still having a natural appearance, which is key within the concept of the picturesque.

This drive to visit popular scenes around the British Isles could be seen as early travel tourism. People travelled out of their habitual environments for short periods of time, with a significant level of curiosity and interest in new places, unseen in the everyday (Urry, 2011:1). The term ‘tourist gaze’ was developed by British sociologist John Urry, which highlights there is “no universal experience” seen by all; our eyes are “socially-culturally framed” (2011:2-3). This means everyone has a different experience out of visiting a new place, due to what English art critic and writer John Berger calls the learnt “ways of seeing” (2008). This is due to

33

Figure 7. Gilpin, W. (1809) Distant view of Rhyddland Castle, Wales [Print]

Chapter Two

different social upbringings and cultures, which is what makes travel and adventure so personal, and ultimately still continue to exist.

Social media has been a significant player in driving picturesque tourism in the modern day, where amateur adventurers are going in search of a “pre-constituted view” of a photograph (Bate, 2019:115) due to its popularity seen online. Instagram accounts such as insta_repeat highlight certain trending touristic locations by collating replicas of the same image taken by different people and sharing them online.

Figure 8 is a current example, showing twelve different images of a skateboarder cruising down a road in front of Half Dome, in Yosemite National Park, USA. This is what British writer and photographer David Bate is describing as the “beauty spot”, where the photographer is in search of a postcard shot, where the image has been arranged so the viewer can appreciate the beauty of the landscape (2019:116). These images are ‘mild’ adventure photographs, as the motif is to seek out a touristic landscape, not a journey into the unknown.

34

Figure 8. insta_repeat (2023) Must be some really good pavement [Instagram, screenshot]

Theories & Ideas within Adventure Photography

Snapshot Photography, and the Snapshot Aesthetic

Snapshot photography is another significant photographic concept seen in adventure photography, which has an innocence and immediacy to it (Bate, 2016:35). It is a raw, dynamic “instant” which hasn’t been premeditated by the person taking the photograph (Bate, 2016:44). A good snapshot photo is one that represents the intended meaning of the event, with little consideration on composition and camera settings (Bate, 2016:39). For this reason snapshot images hold a strong level of authenticity as well as intimacy because they are often personal moments (Holland, 2009:121).

The snapshot aesthetic has derived from snapshot photography, which is the staged or curated photograph in the style of the snapshot (Wright, s.d.).

Adventure photographer Evan Ruderman uses the snapshot aesthetic in his practice, by capturing the in-between moments that reflect the innocence and authentic nature of the occasion, as seen in figure 9.

This black and white analogue photograph taken on a $60 film camera of a mountain hut high in the Swiss Alps has a successful snapshot aesthetic to it. The image feels authentic; there are skis and snowboards propped up against the hut, clothes hung out to dry, and the mountainous

35

Figure 9. Ruderman, E. (2022) Switzerland [Photograph]

Chapter Two

environment giving relevant context to the adventure. This image successfully represents a journey, which is key to adventure photography; the hut is a stop gap to the next section of the story. It also highlights that adventure photography can be as simple as using a cheap point and shoot film camera.

Micro Adventures

A final idea which is important to highlight is the term micro adventure, which was first popularised by British adventurer and author Alastair Humphreys in 2011 (O’Connell, 2023). An adventure which is “short, simple, local, cheap – yet still fun, exciting, challenging, refreshing and rewarding” (Humphreys, 2016). The idea that one does not have to go far and wide with cash in their pocket to experience and feel the benefits of an adventure. This concept is important in order to critique the privilege often inherent within adventure photography. Many of the examples discussed in this research pull from stories from far flung places, with people doing extraordinary things, which would have cost a significant amount of money, training and equipment. The term ‘micro adventure’ highlights one can still experience adventure, even if it is on a smaller scale, by getting into the outdoors, challenging oneself and having fun. Micro adventures can be found almost anywhere, if you think creatively (Pycroft, 2023).

To summarise, this chapter has explored key philosophical theories and ideas seen within adventure photography, from both a historical and modern day perspective. It has demonstrated through examples the huge visual range within the practice arguing that adventure photography can contain elements of sublime, the picturesque, and the snapshot aesthetic, and can also exist on the scale of the micro adventure. The next chapter will begin tracing the evolution of adventure photography, and how the practice has significant commercial links.

36

(3.1)

Geographical Exploration (3.2)

The National Geographic (3.3)

Patagonia Clothing Catalogues (3.4)

Adventure Photography in 2023

39

Adventure

Chapter Three: The Evolution of

Photography

Chapter Three

The aim of this chapter is to show where adventure photography has come from, by investigating its origins of geographical exploration, and how it has evolved through time, by looking at key players such as the National Geographic magazine and Patagonia clothing catalogues. The chapter will also discuss what modern day adventure photography looks like and why it is often commercially driven.

Geographical Exploration

When discussing adventure photography and its history, it’s important to note that the term didn’t exist until very recently. Therefore, this research is tracing the history of a 21st century idea. One of the earliest examples of what we could now call adventure photographs originate from military led expeditions of geographical exploration in the early 1900s (Pycroft, 2023). Prior to the development of the camera, expeditions would have been documented through hand drawn maps, paintings and journal reports (RMG, s.d.). These military expeditions were to increase

41

Figure 10. Hurley, F. (1915) Endurance in Full Sail, in the Ice (side view) [Photograph]

Chapter 3

“topographic visual knowledge” of a nation (Bate, 2019:122), where by using a camera to physically document undiscovered places, increased the power and control of a country, as photographs acted as evidence that these places had been successfully explored.

One of the first significant journeys documented thoroughly on camera was the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Endurance expedition of 1914-1917 (figure 10) led by British Naval Captain Sir Ernest Shackleton (Sherwood, 2022). Australian photographer Frank Hurley was hired by Shackleton to document the crossing of the South Pole (RGS, 2023). Unlike modern adventure photography, what we can now associate as historical adventure photography, was for Queen and Country, not for self (Pycroft, 2023). These were exclusively male explorers seen as ‘heroes’ of their time, investigating and documenting uncharted lands to be consumed by the richer, more educated, white audiences (Armston-Sheret, 2023)

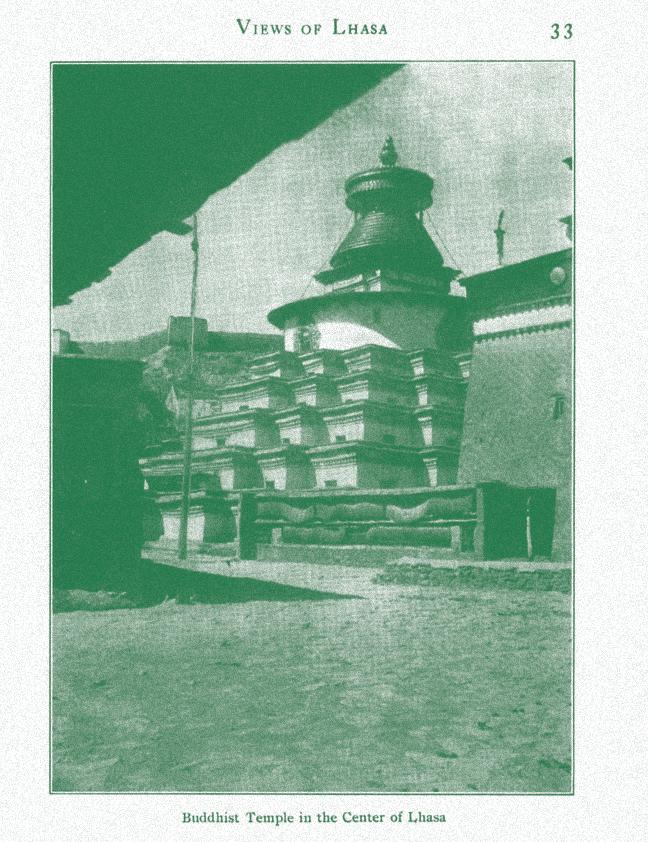

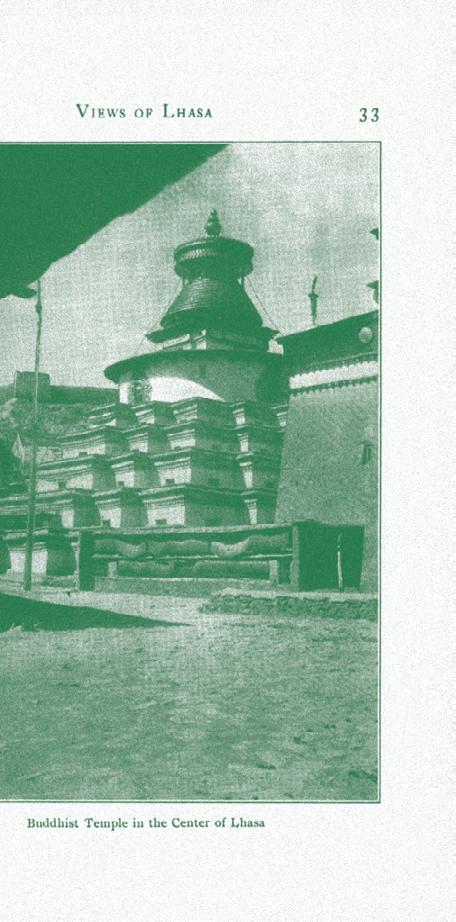

The National Geographic

In the late 19th century an organisation called The National Geographic Society was developed with a goal of “increasing the diffusion of geographic knowledge” to enable millions of ordinary people to see and read about the world (Crooks, 2022). 1905 was their first magazine to feature a photo essay (figure 11) showing images of Tibet (Latorre, 2022).

Whilst inspiring and educating the reader on different countries and cultures, the visual representations of these far-flung places also highlighted that the world is “more available” than we think (Sontag, 2019:24). Photography has been a key factor in driving globalisation; making the world more connected and interdependent, as suddenly places could be documented on camera, which could signify their existence (Alexander, 2015:76).

This idea links into what the American writer and philosopher Edward Said refers to as Orientalism; the East was seen as exotic, and able to be explored and exploited for the gain of the West (Said, 2003:1-3). It is important to highlight the ‘colonial gaze’ here, as many of the early places discovered on camera were occupied territories of colonial controlled empires. Euro-American power enabled these faraway places to be explored and documented, and the photograph was the best way to validate their existence (Alexander, 2015:76). Referring back to Sontag’s point on the

42

The Evolution of Adventure Photography

43

Figure 11. National Geographic (1905) Views of Lhasa, Tibet [Photograph]

“cropping of reality” (2019:122), these places were not just documented, they were often “re-arranged” to show the environments “captured” (Ranger, 2001:203), again to highlight such power, in the height of colonialism.

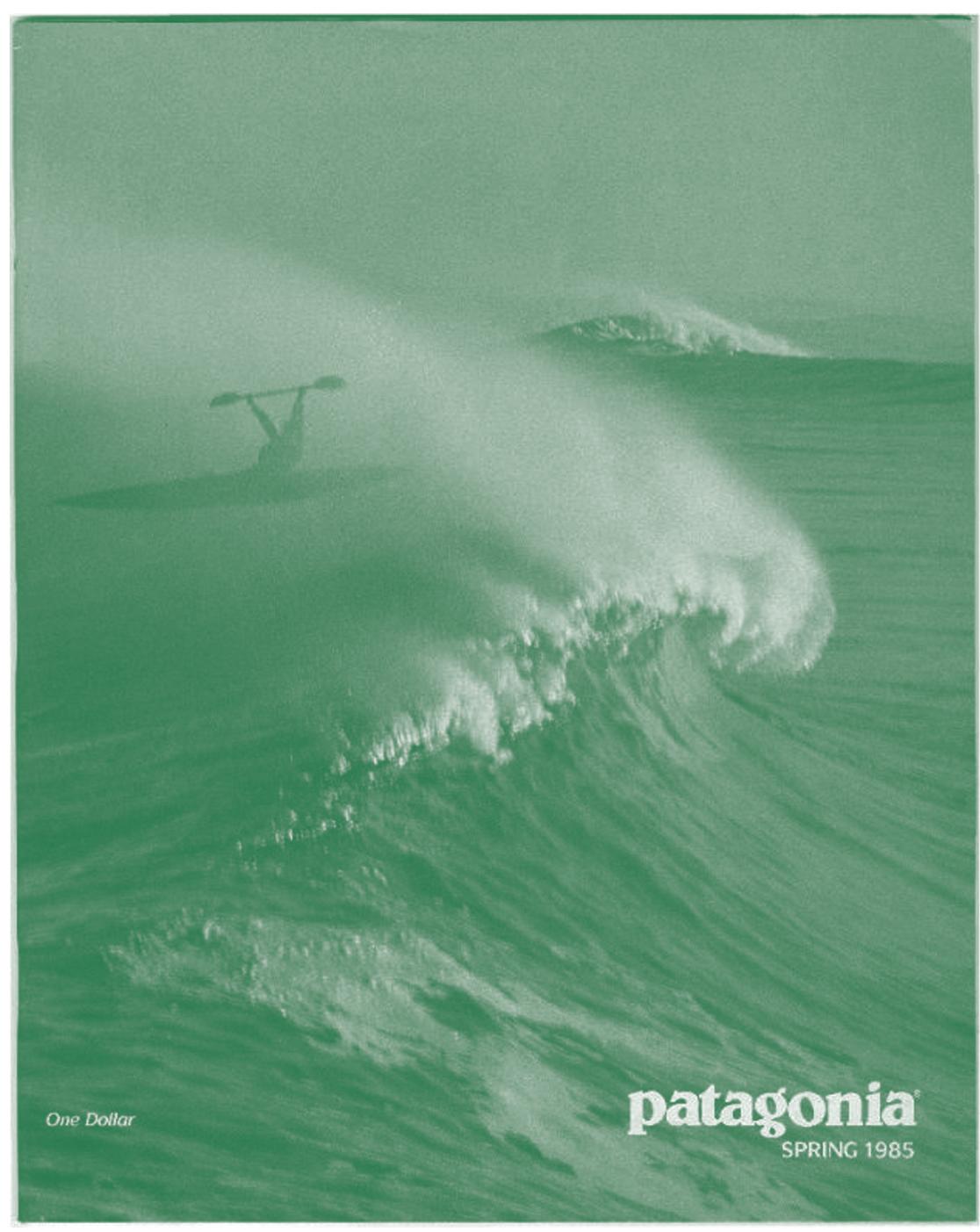

Patagonia Clothing Catalogues

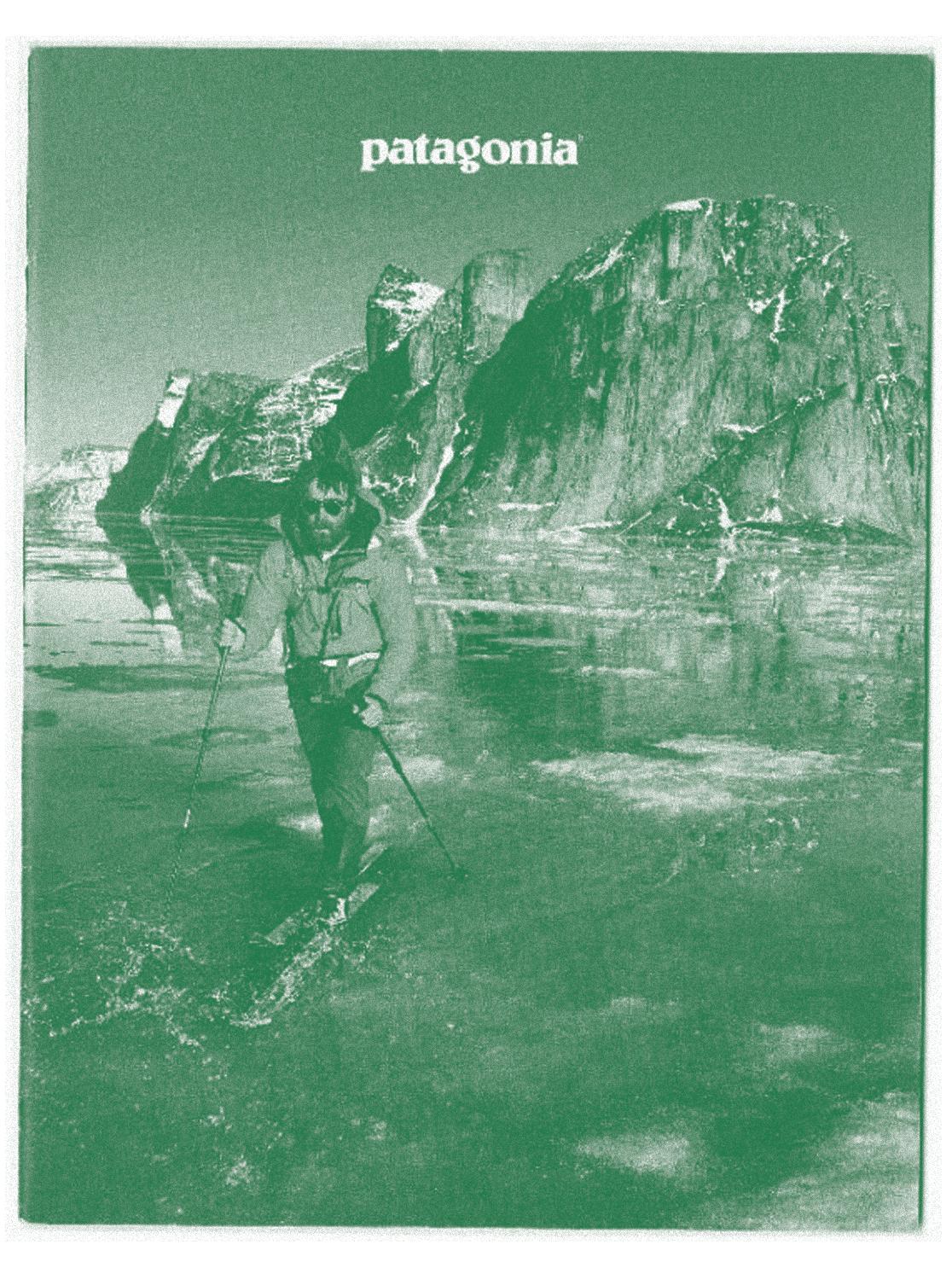

In over a century, the motif of adventure photography has developed from documenting military led expeditions, to educating people on different countries and cultures around the world, to now inspiring others to get outdoors, and go on their own adventures. A key player in initiating this change was the environmental and ethical outdoor clothing company Patagonia. The brand originated in the 1970s from the mountains of Yosemite, California, inspired by the founder, Yvon Chouinard and his friends’ passion for climbing, skiing and surfing (Klein, cited in Chouinard, 2016:viii). In 1981 Patagonia produced its first clothing catalogue, which was more like an adventure magazine, showcasing customers around the world wearing the Patagonia brand in its natural habitat (figure 12), with short anecdotes telling the story of each image, alongside the clothing one could buy (figure 13).

Anyone could send in their images from expeditions, outdoor pursuits, or even from their back garden, as long as they were wearing the Patagonia brand (Ridgeway, cited in Sievert, 2009:8). The concept was called “capture a Patagoniac” and it needed to highlight the “mood, the spirit and the adrenaline” of an adventure (Ridgeway, cited in Sievert, 2009:7). The idea was so successful that 50% of the catalogue is reserved for just photographs to this day (Tuzio, 2022). Figures 14 and 15 show how the brand has kept the spirit of adventure alive throughout the years. Many of the Patagonia catalogue images have an authentic snapshot style to them; people with a love of the outdoors, documenting their personal stories, having fun, and sharing them so that others can be inspired. The concept could be seen as a precursor to modern day social media.

The Patagonia catalogues harnessed peoples authentic and organic adventures and commercialised them, to successfully sell their brand. By adding the brand name on to the original photograph immediately informs the reader where to purchase the right gear to go on a similar adventure, by inserting themselves into the image.

44

Chapter

Three

The Evolution of Adventure Photography

45

Figure 12. Patagonia (1985) Patagonia Catalogue Spring Cover [Catalogue]

Chapter Three

46

Figure 13. Patagonia (1993) Patagonia Pneumatic Pullover advert [Catalogue]

The Evolution of Adventure Photography

47

Figure 14. Patagonia (1998) Patagonia Catalogue Spring Cover [Catalogue]

48

Figure 15. Patagonia (2018) Patagonia Catalogue Winter Cover [Catalogue]

Chapter Three

The Evolution of Adventure Photography

Adventure Photography in 2023

In 2023 ‘extreme’ adventure photography is largely driven by big outdoor brands hunting for “photos and stories from faraway places” to showcase and promote their identity in its most authentic setting (Ruderman, 2023). Images such as figure 16 are used for a variety of commercial outcomes which include advertising, editorial work, or even social media. This change was driven hugely by globalisation, the growth in capital of brands such as The North Face, and the increased development in camera and outdoor equipment.

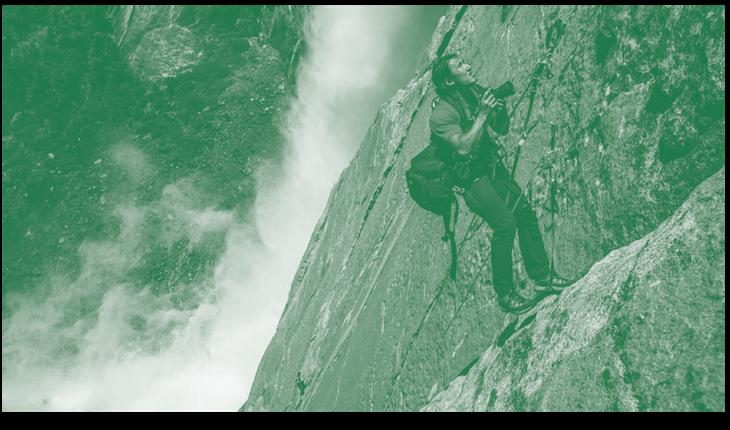

Such a shift has also enabled adventurous people to go on trips and have a part to play in telling a story; a “ticket” to spend a life outside and to travel around the world (Pycroft, 2023). Some of the most famous adventure photographers are elite sportsmen. Jimmy Chin is a prime example as pictured in figure 17; an American professional skier and climber turned Oscar winning film maker and photographer (Van Leuven, 2020).

His specialist skillset and high fitness levels enables him to participate as a photographer in some of the most difficult adventures with matched experience to the main adventurer (Ruderman, 2023). This has created a very elitist and male dominated practice; only allowing photographers with specialist knowledge and physical skills, to work as professional adventure photographers.

‘Extreme’ adventure photography has a significant personal and commercial connection, as illustrated previously in figure 6; the successful first ascent of Devil’s Thumb in Alaska. The clothing and equipment

49

Figure 16. Dumas, M. (2022) Alpine Climber wearing The North Face clothing gear [Photograph]

Figure 17. Schaefer, M. (2018) Jimmy Chin hangs off a line near Yosemite Falls as he photographs climbers on the Freestone route [Photograph]

Chapter Three

companies sponsoring the adventure are getting a huge commercial benefit as their brand is being worn, which can be used for their advertisements. In contrast, for the climbers, the climb is a huge personal achievement which would not have been possible without the commercial backing, therefore, there is a significant personal and commercial connection within ‘extreme’ adventure photography.

However, adventure photography cannot be only commercial, as demonstrated in figure 18 (the repeated diagram). A purely commercial photograph has no story, no sense of journey or exploration. There may be images in an adventure photography style, however, these cannot be classed as adventure photographs. On the contrary to this, adventure photography can be just for self, as seen in figure 19, an analogue photograph I took whilst hiking in the Swiss Alps, which is entirely for my own memories and the hobbyist photographer in me, not to be used in any other context.

Figure 18. Wedderburn, I. (2023) Spider diagram highlighting the key components which make up an adventure photograph [Diagram]

To summarise, this chapter has explored the evolution of adventure photography, from a historical context to the modern day, whilst uncovering issues of colonialism and elitism within the practice. It has highlighted the difficulty in tracing back an idea in time, when there is a lack of formal parameters to the practice today. The chapter has also outlined the significant commercial connection with ‘extreme’ adventure photography. The final chapter will discuss how adventure photography can be used for the greater good.

50

The Evolution of Adventure Photography

51

Figure 19. Wedderburn, I. (2023) Hiking in the Swiss Alps [Photograph]

Chapter Four: The Future of Adventure

Photography

(4.1)

Environmental Awareness (4.2)

Responsibility (4.3)

Sustainable Adventure

Photography

53

Chapter Four

This chapter will look at the role of adventure photography in evoking an emotional response to environmental issues such as climate change, and how this has the ability to initiate change. However, it also challenges the practice and its future, due to the carbon footprint of adventure photographers, and providing possible solutions of practice.

Environmental Awareness

The power of imagery is becoming increasingly important as a way of showing the changes to our planet due to anthropogenic climate change. Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky has devoted his whole career to capturing the impact of human systems which have been imposed upon landscapes (cited in Chrysler Museum of Art, 2018). Figure 20 is a wide angle photograph taken by Burtynsky of a deforested area of woodland on Vancouver Island, Canada, which shows the human damage that is happening to the planet. No statistics, no graphs, just a powerful thought provoking image, with the ability to tell a powerful story and hopefully trigger an “emotional response” (Summerton, 2023), to inspire people to act on climate change.

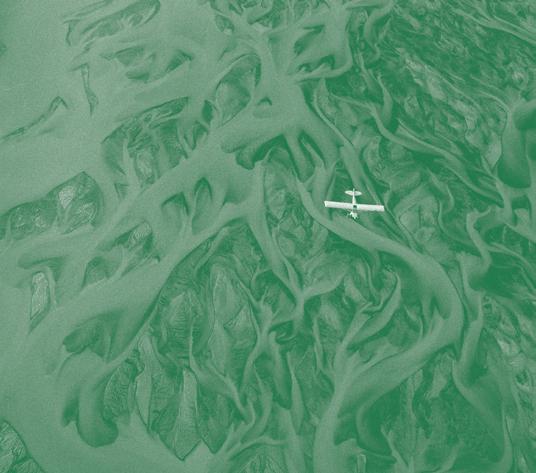

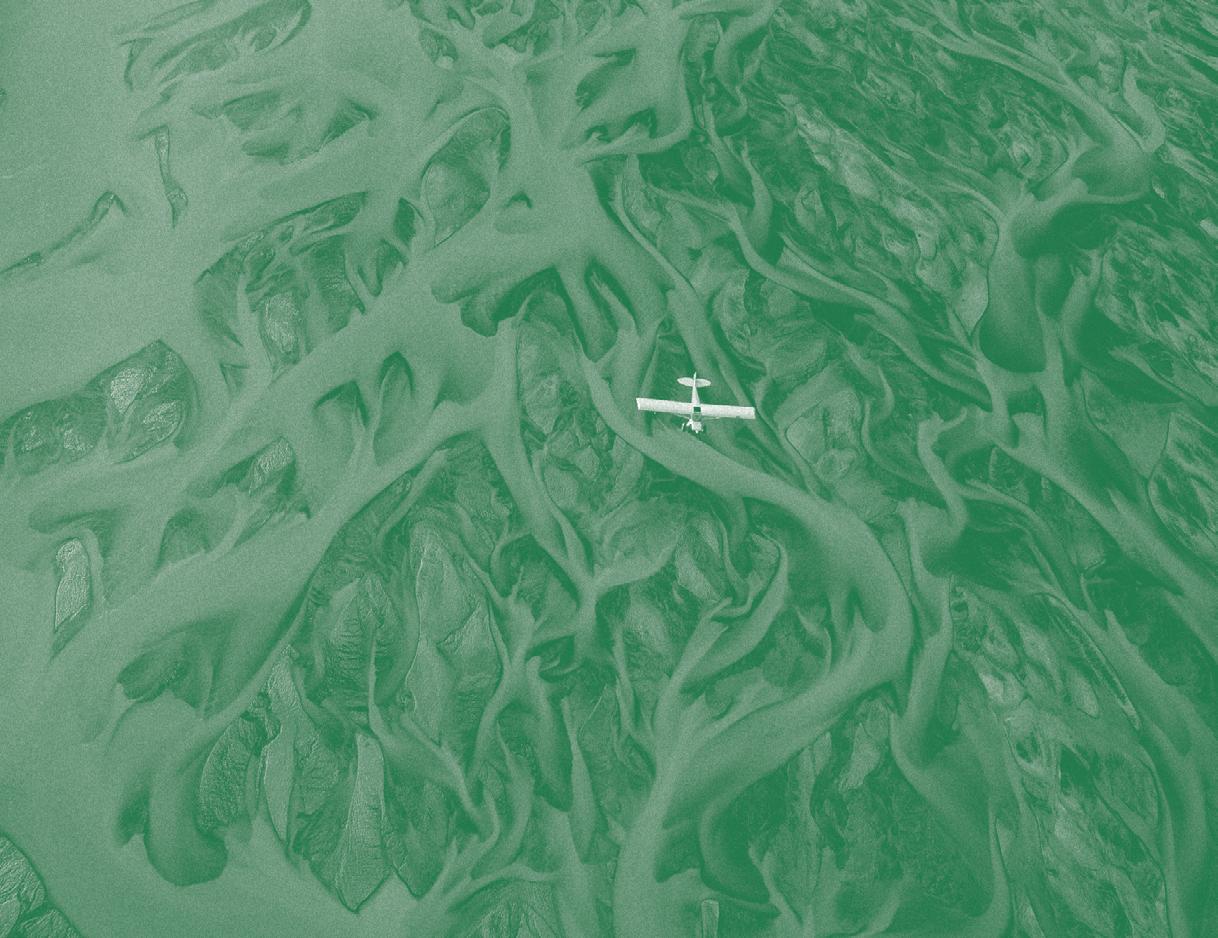

However, positive imagery can be just as powerful as negative imagery (Alexander, 2015:130). Many adventure photographers believe education is key to enabling people to connect with the environment, learn to care for it, and ultimately to inspire action against climate change (Ruderman, 2023). American professional adventure photographer Chris Burkard uses this idea in his practice. Instead of showing the negative consequences of human actions he chooses to show the natural wonder of the planet in all its glory, to try and help people connect with the environment, and learn to love it.

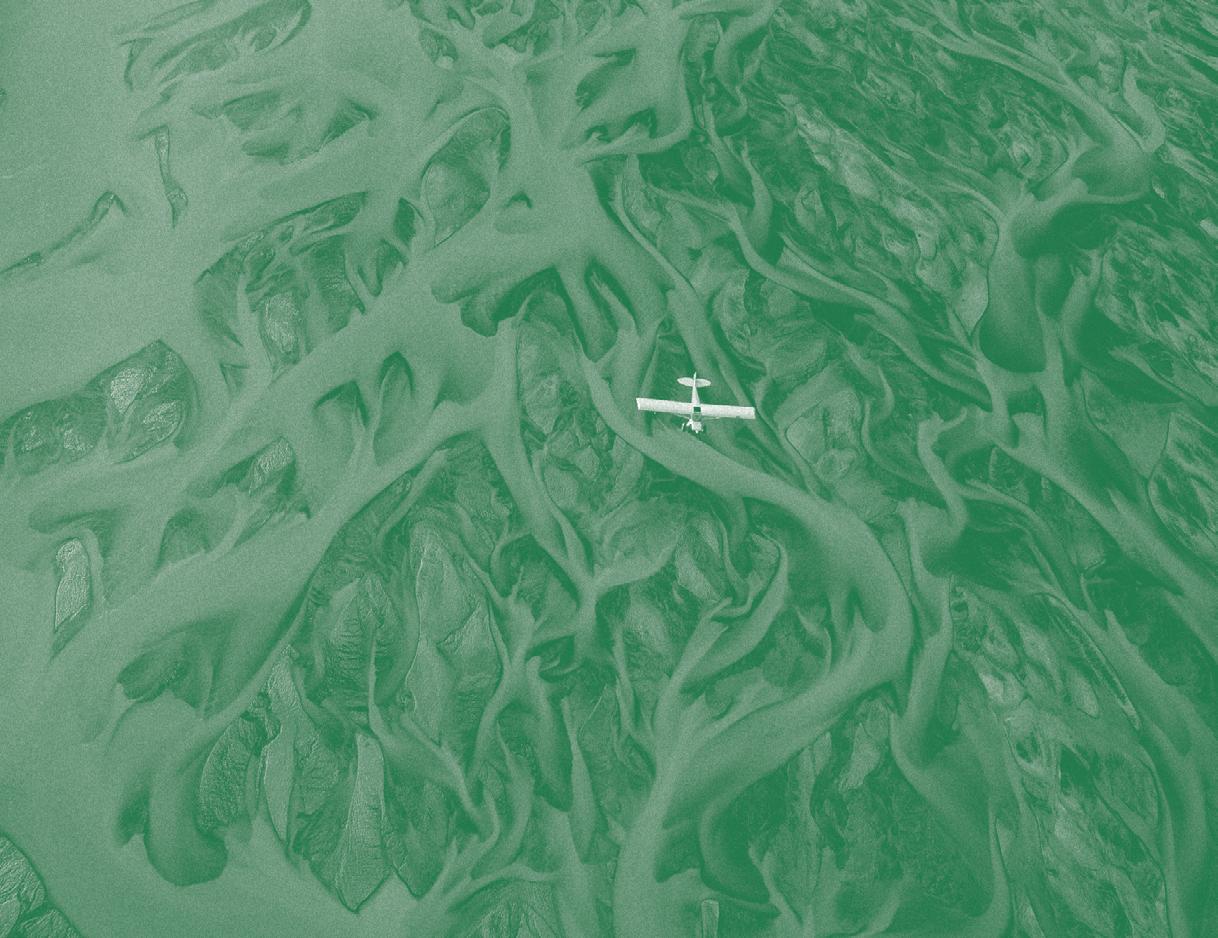

Figure 21 showcases the incredible glacial river systems seen in Iceland. Instead of highlighting the destruction as Burtynsky does, Burkard does the opposite, and captivates us in a mesmerising abstract scene of mother nature working her magic. Burkard often includes a human presence in his photographs which really helps give perspective to the image, which again is a key element in adventure photography.

Using photography as a way of connecting people with the environment is not a new idea. In the 1860s an American photographer named Carlton Watkins started photographing Yosemite Valley (Jarvis, 2016), and

55

Chapter Four

56

Figure 20. Burtynsky, E. (2016) Deforestation on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada [Photograph]

Figure 21. Burkard, C. (2021) Arial photograph of Iceland’s river system [Photograph]

The Future of Adventure Photography

became a pioneer in the development of the National Park Service (Giblett, 2012:74). His photographs (figure 22) were what drove Abraham Lincoln, the President of the United States at the time, to grant a bill to protect the area, and to preserve it for recreational use (MET, 2014). This was the first time a president had protected the environment for the “common good” (Jarvis, 2016), which initiated more areas of land to be protected. This highlights, again, that photographing the natural beauty of the planet, enables people to connect and build a positive relationship with the environment.

This paved the way for the likes of famous American Photographer Ansel Adams in the 1930s and 1940s (Pound, 2023). Adams, like Watkins, had a passion for the outdoors, and photographing Yosemite National Park (figure 23). He was another key figure in educating America on what the great outdoors looked like, and should continue to look like if carefully protected and managed (Pound, 2023). At the time he was criticised for photographing “rocks” when America had more pressing issues like unemployment to deal with (Alexander, 2015:130), however, these images are pivotal in highlighting our planet’s natural beauty, and that we must conserve it at all costs.

There is now an act in the US Government called ‘The Ansel Adams Act’. The bill, granted in 2015 is to enable future people to have the freedom to photograph such landscapes without fees and fines (Hendrickson, 2015),

57

Figure 22. Watkins, C. (1861) Yosemite Valley’s “Best Central View” [Photograph]

Chapter

Four

as his work was so successful in showcasing the beauty and fragility of the world’s natural resources (US Congress, 2015).

Responsibility

Climate change is the “defining issue of our time” (United Nations, 2023). Pycroft believes that we have a “moral obligation” to use whatever skillset we have to help fight the climate crisis (2023). The way an adventure photographer can contribute is by documenting changes in landscapes, helping people connect with issues through the image, and continue to tell meaningful stories.

The paradox is that many professional adventure photographers have some of the highest carbon footprints, due to the very nature of exploring some of the world’s most remote places (Pycroft, 2023). So the question arises, do we need to keep exploring these remote places to be able to continue to tell meaningful stories to promote change? British polar traveller, historian and environmental scientist Tim Jarvis, believes that going to faraway places and physically seeing certain issues gives you credibility, which enables you to connect with audiences which wouldn’t otherwise listen (cited in We Can All Be Heroes, 2023). He describes this as “travelling with purpose” which he believes justifies the travel and the carbon exerted (Jarvis, cited in We Can All Be Heroes, 2023). Jarvis furthers this by asserting that the right people need to go to these places and bring back the stories; if everyone went, the carbon footprint would outweigh the message. Both Jarvis and Pycroft believe to a certain extent that they don’t need to continue to travel to be able to tell meaningful stories; Pycroft has the power to bring fascinating and educational stories to tens of thousands of people with his podcast without even moving from his chair (2023).

Sustainable Adventure Photography

Adventure photography does not have to have a huge carbon footprint as demonstrated by British environmental philosopher, educator and cyclist Kate Rawles. Rawles developed the concept “adventure plus” which is about riding a bike, self-supported in a location which has an urgent environmental story to tell; using the journey as a way to meet people, document the issues, raise awareness and promote action (2012). In 2006, Rawles cycled from Texas to Alaska following the spine of the Rockies Mountain

58

The Future of Adventure Photography

range “exploring North American attitudes to climate change” (2012). She used her photographs and stories to write a book, and subsequent public speaking to raise awareness of these issues, and how adventure can support impactful environmentalism (Rawles, cited in Adventure Plus, 2023). This kind of initiative highlights that we can still travel and take adventure photographs, but at the same time be sustainable and purposeful on our journeys. Rawles’ work is also important to highlight in a significantly male dominated profession (Kennedy, 2018), as illustrated in this research, where the majority of visual examples are from white, western, male photographers. The practice needs to evolve and become more inclusive in order to break down stereotypical norms and assumptions. Role models like Rawles are so important in inspiring more women+ to go outside, and document their adventures, and to diversify the field of adventure photography.

To summarise, this chapter has looked into the power an image can have in provoking an emotional response to an issue such as climate change, critiqued the very practice of adventure photography, and discussed the challenges it faces, whilst providing some possible sustainable solutions for the future.

59

Figure 23. Adams, A. (1937) Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite National Park [Photograph]

Conclusion

61

Conclusion

This research set out to explore the emerging practice of adventure photography; to investigate what it is, where it has originated from, and how it has evolved, and continues to develop its own photographic identity.

The first chapter highlighted through the analysis of my interviews that adventure photography does exist, and is important, but showed a significant lack of understanding and mutual acceptance on the identity of the practice. The development of my own diagrams also signified that adventure photography is very broad and difficult to define; there needs to be stricter boundaries to enable it to have a stronger, more unique identity, and ultimately exist as a formal photographic practice. Secondary research concluded that it shares similar key characteristics to documentary photography, therefore, adventure photography could possibly sit within the genre of documentary.

The second chapter went on to investigate the different ideas seen within adventure photography, such as the sublime, the picturesque, and the snapshot aesthetic. However, not all these ideas are present all the time, in all images. Therefore, this research showed the significant visual range within the practice, which can make the identification process of an adventure photograph even more challenging.

The third chapter highlighted that tracing adventure photography back in time is difficult, as it is a 21st century idea, which hasn’t been culturally agreed on yet. This conclusion was met by investigating the origins of adventure photography, by looking at historical military expeditions, the National Geographic and Patagonia clothing catalogues.

The final chapter highlighted that current forms of adventure photography can have negative environment consequences. Despite this, it also concluded that adventure photography can play a huge role in raising awareness of environmental issues, through the power of imagery, as demonstrated by the likes of Edward Burtynsky and Chris Burkard. This could indicate a new future identity, focussed less on people, and more on the environment.

I am also aware there are many other important debates and topics which exist within this field. Future research should focus on exploring the history of adventure photography in more depth, particularly female adventurers, and further investigate different modes of travel as a way of exploring new environments.

62

Conclusion

This research is an important contribution to photographic literature as it has uncovered, identified and explained a new, emerging photographic practice, whilst highlighting the problems it faces in developing its own distinct formal identity. The hope is that this research will encourage others to build on the ideas I have proposed, and further develop the practice of adventure photography.

From undertaking this research, my passion for photography, adventure, and the outdoors, has significantly grown. I have discovered a topic which I am increasingly curious about, and excited to further explore within my own creative practice. I have career aspirations of working for an outdoor adventure publication, to enable me to continue to develop my editorial design and photographic storytelling skills.

Based on the research carried out, I propose three ways adventure photography can move forward as a practice. Firstly, it needs to diversify, and become more inclusive, to break down stereotypical norms and assumptions. By supporting more women+, and people of colour as adventure photographers, the practice will not only diversity, but the variety of stories and adventures will also broaden, which will positively impact the evolution of the practice. Secondly, adventure photography needs to become more accessible; financial consideration needs to be given to both the cost of camera equipment and the scale of adventures, to those seeking to work within the practice from a variety of socio-economic backgrounds. Finally, the practice needs to not only educate, but empower. Adventure photography has the ability to impact the relationship we have with the outdoors and natural environment in a positive way. Therefore, it has a responsibility to not just inspire, but to empower people to act on key environmental issues, such as climate change.

63

Appendix A

Transcript of Interview with Evan Ruderman (67)

Appendix B

Transcript of Interview with Sidetracked Magazine (79)

Appendix C

Transcript of Interview with Matt Pycroft (87)

65 Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix A: Transcript of interview with Evan Ruderman Date: 07/08/23

Location: Remote via Microsoft Teams

Interview Length: 35 minutes

About: Evan Ruderman is an American adventure photographer, who for the past three years has been working for the renowned adventure photographer Chris Burkard, working on commercial adventure photography projects all around the world.

How long have you been working as a photographer, and who have you worked for?

I have been working as a photographer for four and a half years now, I started in May of 2019. I was in college and went to the University of Michigan, and I just applied for an internship in California with Chris Burkard - just a cold email. I didn’t really know what I was going to do after college, I loved shooting photos, and I was like “cool let’s give this a try”, and it ended up working out. So I came on with him as an intern, and worked for him as an intern for like six months, transitioned into full time, then to second assistant, and transferred into first assistant, and then was his right hand man for a few years. And last October I transitioned out and became freelance. Now I work for myself which has been only a little less than a year now which is crazy.

I worked for Chris Burkard and along the way I got to meet and work for a lot of other photographers – shoot to shoot basis – a lot of other big names in the industry which was really great to learn from them and ask them a few questions, and make some connections.

But in terms of full on professionally, I have only worked for Chris.

67

What made you want to become a photographer in the first place, and in particular focus on outdoor photography?

I think that it all just stemmed because I loved to be outside, I loved to be exploring, and I think it kind of happened naturally where I was shooting a lot of photos outside, and I was having a lot of fun, a lot of the stuff I was doing was action sports related, in terms of snowboarding and mountain biking and doing a lot of these outdoor activities and I eventually started to learn that people around me were a lot better than I was! The easy thing to do is - well I guess I’ll keep hanging out with them doing these things, but I’ll bring a camera along and shoot photos of them doing crazy flips that I’m not willing to do!

So that’s sort of how my interest in photography started. When I was young in middle school and high school, I had my first camera. I grew up in New Hampshire which there isn’t a whole lot going on. My town had one restaurant, one gas station, and one little mini grocery store so me and my friends spent most of our time outside just trying to have fun, and I would bring the camera along. And then in terms of pursuing it as a career, it never seemed like anything that I was going to do, it was something I was doing for fun. And then I lived in Chile for six months, I studied abroad down there when I was in college.

So I was a junior in college, I was trying to figure out what I was going to do, I was travelling down there and shooting all these photos, and just having so much fun. I told myself like this is really what I want to do, before it’s too late I am going to do whatever I can to try and somehow to this. So I just promised myself that when I come back, I had one more year of college to finish, and in some form I was either going to work as a photographer or take a year off and travel and shoot photos and backpack around. So I applied for an internship that I really didn’t think I’d get. My secondary option was I was going to go and try and live in somewhere in South America, and teach English

68

Appendix A

Evan Ruderman

and shoot photos. Luckily I got the internship and somehow I am here which is crazy.

If you had to describe “adventure photography” to someone who had never even opened a National Geographic let along heard of one, how would you sum it up into one sentence? That’s tough! I would say that adventure photography is the art of documenting exploration. I think that that’s an easy one sentence to tell somebody, but I think, the first thing that came to mind to me is that adventure photography can mean so many different things to so many different people. I consider myself an adventure photographer, a lot of other adventure photographers probably don’t consider my adventures, adventures.

I spent some time with Ted Hesser, he is a really renowned adventure photographer, on the spectrum of adventure he’s like at the far end. He’s with Jimmy Chin going to Antarctica and in the Himalayas and doing crazy things that probably makes my photos and adventures not these crazy adventures. There are probably people who consider themselves adventure photographers who are just going for a walk in their back yard. So on that spectrum the adventure can range so much, and whatever anyone is doing is… it feels like adventure photography… do whatever you consider an adventure.

I think that one big thing is that it’s a little more focused on documenting, as something is happening, as you are going on a trip, as opposed to other forms of photography which are really focussed on setting thing up and producing things to look a certain way, but I feel like with adventure photography, a big portion of it is shooting things as they happen. You can’t control the weather, you can’t control what a certain landscape is going to look like. A lot of times you are going far away and you are like “I hope this looks pretty”, but I don’t know, and I think that this is a big distinguishing factor.

69

What do you think the role is of an adventure photographer? I remember Chris Burkard talking about his purpose of “spreading joy”. Do you think that is enough, or do you think that there has to be a deeper meaning?

I think peoples appetite for adventure is very different. Some people are willing to go on these crazy adventures and put their lives in danger to climb a mountain, which is awesome, and some people would never do that. But kind of like the thing with spreading joy it’s that both of those people are happy then all is well. Nobody should force themselves to do something they don’t want to do. I think those people who go on those insane crazy gnarly adventures are driven to do that because they want to, I don’t think people should do that if they don’t want to. And the people who are happy in exploring their own back yard, and that’s awesome that they are happy too.

Aside from what you want and don’t want a lot of the pulling factors for people financially, not everyone can go on a crazy trip with the North Face to Antarctica. So if you can only go and do a local camping trip with your friends, that’s a few miles away, that awesome too. People shouldn’t be dissuaded to go shoot photos and shoot adventures that aren’t really big and grand just because other people have access to doing those things you know.

What are your thoughts on privilege? Do you think you have to travel significantly far away to practice adventure photography?

I was talking to another photographer just a few months ago we were chatting and I was explaining wanting to go to all these faraway places and shoot these photos, and he was saying to me, you should have a style, you should have the ability to shoot a really good photo in your back yard. If somebody wants to hire you to shoot these photos far away, they should also want to hire you to shoot photos in your back yard. You have an eye for something, and you

70

Appendix

A

Evan Ruderman

can make different scenes look really great and so you should feel encouraged to go shoot close to home not necessarily super far away.

Adventure photography comes is very broad, how would you describe the modern adventure photographer?

It used to be a lot driven by scientific exploration, in that’s now its driven a lot by commercial interests, so on that note of funding, it’s like all these people… it’s the same now as it was then, there’s people with a really big appetite for adventure who want to go to some really faraway place, but it costs a lot of money, and you start to think, well how can I get this paid for, because I can’t pay for it myself? And I think a long time ago that was largely focused on science, people were willing to fund these scientific exploration quests, nowadays that’s not so much, but all these big commercial brands want these photos and stories from faraway places. So a lot of these people who probably deep down just want to be adventurers alone, if they could they’d just go and do an awesome adventure and come home. But shooting photos and filming videos is a way to get that funded. I think a lot of these people, these adventurers have now kind of blended into commercial photographers because there is kind of a blend between this, and that’s a way to go on these adventures. So I think the modern adventure photographer and modern adventurer has just become also a very talented commercial photographer at the same time. It is an interesting intersection but I think it’s the way to pay the bills and to get the opportunity to go to these really cool places.

How powerful do you feel the camera is as a method of storytelling?

I think that it’s incredibly powerful, it’s like the age old saying “a photo is worth a thousand words”, I think largely the power relates to how good the images you

71

are shooting. I think people… you can take an image with your phone really quick and not think about it, and doesn’t tell that much of a story. Sometimes you see a photo on the Internet or on Instagram, and it stops you in your tracks because it’s so powerful, and the whole thing tells a story and makes you feel a certain way. I think that’s when you know what a good photo is.

I’ve noticed from your Instagram that you enjoy taking analogue photos for personal adventures, could you explain why this is the case? Do you find they hold different memories?

I think a big part of the image and of the photo is trying to tell a story through the photo and trying to be really meaningful of what you are shooting and why you are shooting it. I think for me between having a phone in my pocket with a camera that I shoot like a gazillion photos on a day, a really nice digital camera which I’ll go on a shoot and shoot tens of thousands of photos with, that shooting with the film camera is just a practice of trying to really slow down and think about why I’m shooting each thing. What am I really trying to achieve with this one photo that I am going to take and what angle will I make the best, and what story can I tell. I think it makes me slow down and really focus on what I am shooting. I think a lot of people feel that way about film, partly because its expensive but the other side of that too is that I shoot so much digital photos. Like I said with the adventure and commercial photography blending, a lot of times when I go on these adventures I’m shooting for brands and clients and a lot of these photos pile up, and I shoot thousands of them, they are for brands and they have products in them, so I often try to keep the film just really personal. For example I went to Patagonia last fall, I shot photos for three different brands so I shot a few thousand photos and had to edit them and send them to the brands, but I shot like three rolls

72

Appendix

A

Evan Ruderman

of film. It’s like one hundred photos and I find myself a lot when people ask me about the trip, and how was Patagonia, a lot of the times I’m pulling up the film photos because they were the funny memories at like the campsite, things aren’t perfect, and there is no branded logo; somebodies eating ramen and I just find film really fun. A running joke I have with my friends is that these film photos are the ones we are going to show our kids. It’s ironic because I have a sixty dollar film camera and a very expensive digital camera. I feel like in twenty years when someone wants to see photos from these golden days of our twenties, it’s going to be these random film photos we pull up over all the fancy nice photos.

How does your practice connect you with the physical natural environment?

The biggest goal of this career was to spend a lot of time outside, so I’m lucky in that my time shooting photos correlates directly with spending time outside, and searching for cool and faraway places so I’m very lucky for that, but a big part of my career is spending time in nature and connecting with nature and trying to take photos in a way that people will appreciate and enjoy.

What are your thoughts on the physical requirements of being an adventure photographer?

On these assignments it’s the photographers responsibility to be able to keep up with whoever he’s documenting. A lot of the time it is really hard as you are documenting professional athletes; people who are dedicating their lives to a certain sport, as a photographer you are probably documents a lot of different things. But I think part of the job is staying in shape and being prepared, and it’s kind of what you sign up for. But I think like being aware… I don’t really shoot climbing it’s because I know if I were to go on an assignment with climbers I don’t know how to deal with

73

ropes or climb and shoot photos at a level that would be expected to go shoot with professional climbers. So I think a lot of it is self-awareness; “okay I can do this, or okay I can’t do that”. I try to be in shape and be prepared for what’s going on. Before I go on an assignment if I know it’s going to be like - okay I’m shooting snowboarding this week I’m going to make sure that every possible thing I can think of is covered in terms of like “okay I’m going to be shooting out of my backpack, and there is going to be a tonne of snow so I should put these things in these bags, I should have gloves I should have mini gloves under”, so I could be shooting photos and not slowing the team down because who really wants to bring a photographer along who is just slowing everyone down? A big part of it is preparing yourself to keep up, those are all the things that go into this profession behind the scenes. Nobody is paying you or making sure you spend a week prepping your gear, or going on long runs, and training yourselves to be ready. I think those are the things that separate a good photographer form an average photographer. I learned that through Chris because he’d go travel somewhere and he was always moving a hundred miles a minute and I was expected to keep up with him. Quickly I learned that, that is part of the profession is being ready.

Do you think the physical requirement of adventure photography is what puts it apart from other photography practices? It certainly makes it unique, when you look at these photos you remember that you were there too, all the photos you shoot, obviously you are behind the camera, but you know that you were in that crazy place too, it’s not you smiling on top of a mountain, but you know you were there and sweaty and had your camera bag and putting all the pieces together. I think that is special, I think that it’s really rewarding. Like we said it’s about documenting the experience and some people would much rather be in front of the camera the whole time, but some people would rather be behind the

74

Appendix A

Evan Ruderman

camera documenting it and shooting it in the way that they want, and that is what I’ve always preferred. When I look at all my photos of my adventures I never think “oh I wish that that was me in front of the camera” I’m just like “that was so cool I got to go there and shoot photos of this person”. It’s a special way to look back. And I think that is kind of the big idea with adventure photography; it’s to look back and know how much struggle went into all those images and all those adventures and look back and smile, even though you were probably miserable in the moment. In a lot of the adventures you’re there and its brutal and your tired, cold and out of breath, sore, and you are like why am I doing this? This is terrible! My friends are at their desk and I would way rather be at home. But then a month later you look back at the photos and go “oh yeah, that was awesome!”.

What is your stance on using adventure photography as a tool to highlight climate change?

I think it’s really important. I actually studied environmental communications in college, so my long term goal was to pair photography with environmental communications and speaking about climate change and these pressing issues. Its conflicting because at times it feels like people could probably be doing more productive things. My brother works in environment sciences; I am out shooting photos and he is out writing scientific research that is probably more significantly important. But a view I adopted largely from working with Chris is, you have to make people care about the environment, that’s like the foundation. You could write a million scientific articles, you could have perfect proof that climate change is happening, we need to stop it but nobody is going to act upon anything that they don’t care about. Everything we do is rooted in emotion, the baseline to get someone to care about something and to be active and to create action is for people to care about something. I’d like to think that adventure photography and outdoor

75

photography is a way to make people care about these things. At times I thought that was a racialisation but the more I’ve reflected on it there is a huge interest in the outdoors these days. At least in the States the National Parks are crazy, everyone is going to them, the beaches are crazy, going to get permits to do all these hikes, and I feel like a large reason for that is how big outdoor adventure photography has become and social media. How this generation of people are raised, seeing all these photos and videos and dreaming of the outdoors, and how they are getting older and going and experiencing these places for themselves. Now I’d hope that, as they spend time outside and as they do these things and start shooting photos of their own, that they will care about protecting these places and be a little more active on climate change measures. There needs to be an emotional connection. Documentation too, like seeing these before and after photos of places like in Iceland where they have dammed these amazing rivers or places are drilled for oil, reading the words on the pages is important but flipping the magazines and seeing “holy crap” this really happened, they really built this… those are the things which really tricker an emotion response and hopefully make people care.

Who are your photography role models, and why?

Tough question – there were a lot of them! Obviously working for Chris, he was a photographer I looked up to for a long time, and then getting to work with him for four years I learned a lot from him, over the course of my time with him, and I don’t think I would be where I am today without having worked for him. So certainly him, and through him there is a really cool network of photographers of where I live in San Luis Obispo who are cool to look up to and bounce ideas off of. There is a network of guys like Ryan Hill, Russel Holiday, Ryan Valasek, those are all local people which is cool. And then some others, there is

76

Appendix

A

Evan Ruderman

one photographer Mike Dawsy, he’s a snowboard photographer. I look at his work all the time because it’s so incredibly good – every photo he shoots and posts is amazing, and its unique. And when I look at his photos and I think “dang, I really need to think about things more and push myself creatively”, because he does some really cool stuff. I feel that way with one more photographer Jerome Tanon, he is also a snowboard photographer, he shoots everything on medium format film and it’s really cool. And a lots of the time he takes these slides and etches them and scratches things into them develops them and prints them really big and it’s really cool. He made this book called ‘Heroes’ and it’s about all these female snowboarders. His work is really cool and unique. It’s fun to see photographers think about something and put time into one creative vision as to opposed to just shooting things for social media. It’s always finding people who are like really working hard on one thing and putting a lot of time and effort into it, it’s cool.

77

Appendix B: Transcript of interview with John Summerton (JS) and Alex Roddie (AR) from Sidetracked Magazine

Date: 07/09/23

Location: via email

About: Sidetracked Magazine is a British lead publication focusing on telling stories of adventure and exploration. John Summerton is the creative director and head graphic designer for the publication which he started in 2014. Alex Roddie is the chief editor of the magazine, who also writes for a variety of outdoor publications and publishers such as gestalten and The Great Outdoors Magazine.

What is the story behind Sidetracked? How and why did a magazine based on powerful storytelling in the outdoors begin?

JS: Sidetracked Magazine is a niche adventure and exploration publication that features stories, photography, and articles about extraordinary journeys and outdoor experiences. It was founded by John Summerton (a graphic designer and typographer who has a passion for the outdoors and exploration) in 2011 and first went to print in 2014. The magazine’s aim is to inspire readers to embark on their own adventures and discover the beauty of remote and untamed landscapes.

Each issue of Sidetracked Magazine typically contains captivating narratives, stunning photography, and in-depth interviews with adventurers and explorers who have embarked on remarkable expeditions. The magazine covers a wide range of outdoor activities, from mountaineering and wilderness trekking to kayaking and extreme sports.

Sidetracked has gained a dedicated following among outdoor enthusiasts and adventure seekers for its high-quality content and its ability to transport readers to some

79

Appendix B

of the most remote and breath-taking places on Earth. It continues to showcase the spirit of exploration and the thrill of discovering the unknown.

Why do you believe printed magazines such as Sidetracked should continue to exist in an increasingly digital world?

AR: If anything, I believe that print is more important now than it has ever been – by far. Although we live in a world of digital abundance, the infinite feeds we scroll through don’t encourage immersive reading experiences. Instead, they encourage distraction, simplification, and a flattening of nuance.

When reading on devices – especially if our reading material reaches us through social media – we flit from story to story, barely seeing more than headlines and a sentence or two, maybe bouncing listlessly from image to image before scrolling on to the next story. Infinite quantity is not the same as quality (in fact, I believe they’re inversely proportional). The architecture of the web simply isn’t designed to encourage deep thinking. It’s designed for shallow reactions and blunt emotions.

Print, by contrast, stands against the infinite content black hole of the web. If you have chosen to spend money on a magazine, sitting down to read it is already more of an event. You’re invested in paying attention to it. The design of a well-crafted print magazine is also significantly more attractive than the vast majority of websites, which are polluted by obnoxious ads (including auto-playing video ads), further breaking down any immersion. Even the best websites can’t approach the reading experience of print. Details, such as typographic nuances that don’t even exist online, matter a great deal.

Finally, revenue models for paying creators on the web are shaky and unproven at best – and although print certainly has its challenges, we are able to adequately pay photographers and writers for the high-quality work they

80

Appendix

B

John Summerton & Alex Roddie

offer. This also ties in to our rigorous editorial process involving several experienced team members, all of whom are committed to the best possible quality.

The end result is a more engaged reader who is paying more attention to a better-quality product, and therefore gets more out of the whole experience. It works for everyone.

How would you describe adventure photography in one sentence?

AR: Adventure photography is about storytelling: conveying character-led moments in a narrative through strong, simple composition, as well as immersing the viewer in the setting.

What do you think the role is of an adventure photographer / videographer?

JS: Specifically relating to Sidetracked, adventure photographers and videographers play a crucial role in bringing the stories of exploration and adventure to life. Here’s why:

Visual Storytelling: Adventure photographers and videographers are responsible for capturing the essence of the adventure and conveying it to the audience through compelling visuals. They use their skills to tell a story, showcasing the beauty of landscapes, the challenges faced, and the emotions experienced during the journey.

Creating Immersive Experiences: Through their photography and videography, they enable readers and viewers to immerse themselves in the adventure. Their work transports the audience to remote and awe-inspiring locations, allowing them to experience the thrill and wonder of the expedition.

Documenting Authenticity: Adventure photographers and videographers aim to capture the authenticity of the adventure. They document the raw and unfiltered moments,

81

portraying the highs and lows of the journey, which adds depth and realism to the storytelling.

Inspiring Exploration: By showcasing stunning imagery and videos of remote and untouched landscapes, these visual creators inspire others to embark on their own adventures. They encourage people to step out of their comfort zones and explore the natural world.