5 minute read

Living in a material world

from Subject Matters II

Living in a material world (2020)

“The true reality of an object lies only in a part of it; the rest is the heavy tribute it pays to the material world in exchange for its existence in space.”— Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet, New Directions, 2017, p. 76.

Architecture exemplifies this observation. Buildings fall into two broad categories—those that aim for this pared-down essence and those that make a display of the tribute paid. Bucky Fuller idealized the former, seeking lightness in the manner of Zeno’s paradox. His self-proclaimed disciple Norman Foster makes a fetish of the tribute, structure rendered as ornament.

So-called minimalism, if mired in materiality, uses endurance as its building blocks or shrinks things—tiny houses, guestroom capsules, sleeping pods—in hopes we won’t notice their solidity. Traditional Japanese houses, with demountable wooden frames, and tatami mats and shoji screens that are ephemeral by design, are the exception.

At a certain point, Fuller introduced time into his concept of lightness. His four-dimensional houses were as physically light as he could make them, but they were also intended to be lived in only when needed. If this idea is played out, everything might change. We can imagine a service economy in which a fresh set of clothes follows us from place to place, arriving in the night. For ultimate portability, even our shoes might change—espadrilles, sandals, clogs, or boots instead of shoes designed more exactly for our feet. We may retain one seasonal outdoor pair, shed each quarter.

To extend Pessoa’s observation, this lightness also involves a sleight of hand, an apparatus no less weighty for being external to the houses it serves. The burden of it is carried by others. As we dispose of retail, the goods we still purchase come from warehouses in delivery trucks. Despite the threat of automation, workers still handle this. Artisanal workshops and the specialty markets, breweries, and restaurants and cafés associated with different locales are the walkable counterpart. How the great “houses” of art, design, and fashion find a place is not yet clear to me. Perhaps they form networks of affiliates that both produce bespoke goods and import them for their high-end clientele? If life is local and segmented, retail rents will fall back to earth. The food and

beverage business will split between the commodities and imports obtainable in bulk and what a region’s farms and vineyards raise to sell seasonally to local buyers through local shops.

Warehouse retailing may come to reflect the way politics is affecting trade. The urge to decouple from China reflects a clearer sense of the weight of the tribute. This can be extended to intellectual property, for example, which we’ve often handed over to gain access to a market we saw as vast and steadily wealthier. True, but also a market innately given to import substitution. Ironically, architecture was a leading indicator—the high-grade steel and tailored façades imported from Korea were supplanted by Chinese models five years later—reinforced by a mercantile economy. China needs somewhere to which to export its factories. Southeast Asia has priced itself out, so Africa is the logical choice—resource- and labor-rich. China will revive its countryside, recreating a docile, agrarian village cohort and tone down its restless cities. Only the bought-off, upwardly mobile middle classes will thrive in cities, served by an underclass of ambitious migrants. Industry will be tamed and pollution will be reduced. All that will move to Africa, which will grow fetid catering to this new colonial power.

The big democracies—Brazil, the U.S., and India—resemble each other in their contradictions. Parts of them aspire to rise to a higher standard; other parts are mired in corruption and ignorance. But they can no longer hide their problems. They will either reform together or experience greater fragmentation. Regions, to the extent they control their own fates, will see smaller versions of the same divisions.

A kind of soft oligarchy is already in view, making concessions to the underclass at the expense of the professional middle class to remain in power. Progressive politicians negotiate this process. They extract concessions and buy the support of blocks of voters who feel shut out and blame the professional middle class for this. New national policies to tax the sources of oligarchic wealth may undo this regional condition, forcing corporations to pay the real cost of their regional impact, another sleight of hand.

“Object” in Pessoa's sense should find wider application—not just to buildings or blood diamonds, but everything that trades on its surface appearance and keeps its workings hidden or unmentioned, whether it involves sweatshops, exploited labor, pollution, or profits

that in a societal sense are unearned and even grotesque. The rest is too large, too out of scale with everything around it, to be ignored. We have to reckon with its true reality: the size of the tribute.

Posted on my Medium site (johnjparman.medium.com) on 12 December 2020.

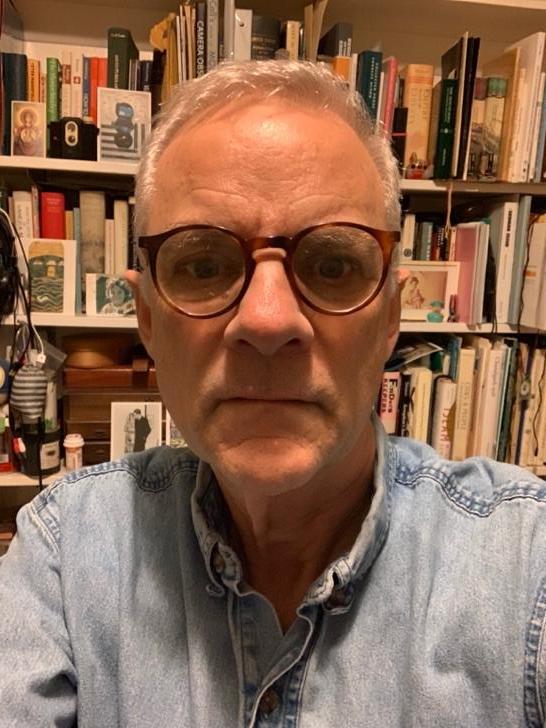

John J. Parman is an editorial advisor to ARCADE, Architect's Newspaper, ORO Editions' A+RD research imprint, and Room One Thousand, the annual edited by graduate students at U.C. Berkeley's College of Environmental Design, where he is a visiting scholar. In 1983, he and Laurie Snowden founded Design Book Review, edited by Richard Ingersoll and Cathy Lang Ho, and published it until 1998. In 1989, he and Richard Bender founded the Urban Construction Laboratory to address a range of urban topics. In 2019, he and Elizabeth Snowden founded Snowden & Parman, an editorial consultancy, continuing their ongoing collaboration.

Educated in architecture and planning, Parman lectured at U.C. Berkeley and California College of the Arts in the mid-1980s and again in 2004. He had a 40-year career in the field, with stints at EHDD, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and then at Gensler, where, as editorial director, he launched two of its flagship publications, Dialogue(2000) and the Design Forecast(2013). His team's work received the highest awards from Graphisand Arc International, and was twice a finalist for Folioawards for editorial excellence.