8 minute read

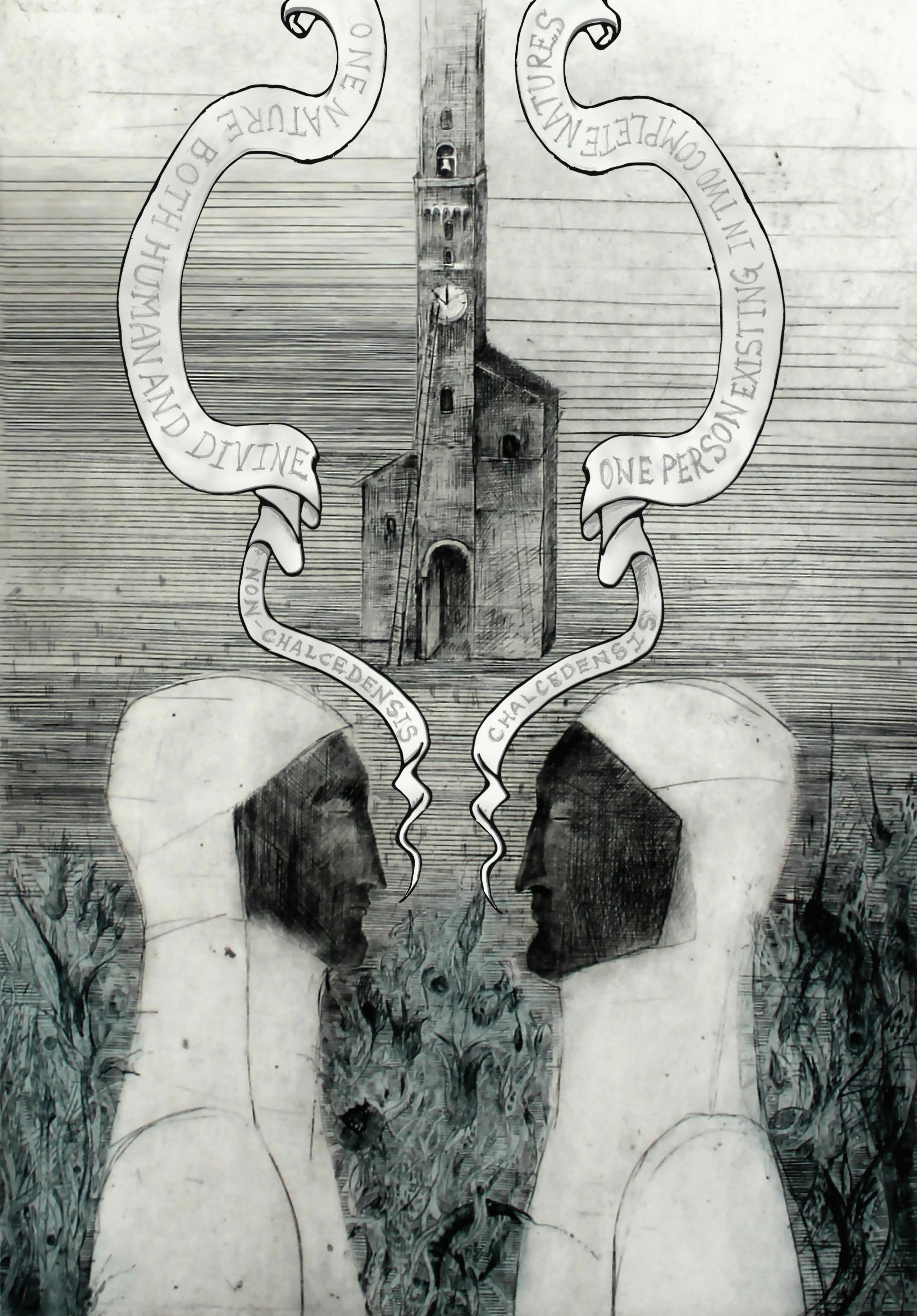

The Myth of the "Monophysites"

by STEFAN JOHANSSON

Church history is anything but smooth. Many of us like to say that before the schism of the Roman Church from the East in the eleventh century, there were “no denominations” and “it was all one Church.” This is not exactly accurate. Throughout the first millennium of Christianity, there were plenty of factions that fell out of communion with the Orthodox Catholic Church. Every one of those groups is now essentially gone — though some of their beliefs may linger in groups that exist now—so it is easy to forget about them or brush them aside. Well, all are gone except for one. Today we call them the Oriental Orthodox or non-Chalcedonian churches, but in centuries past, we inaccurately deemed them “Monophysites.”

Advertisement

The conference we consider to be the Fourth Ecumenical Council, held in Chalcedon during the year 451, was ultimately rejected by many faithful Christians of Egypt, Ethiopia, Syria, Armenia, and India. But the Oriental Orthodox have stood the test of time, maintaining liturgical integrity and impressive piety and offering countless martyrs. It is for these reasons that in our communion of Eastern Orthodoxy, many people have come to believe they in fact are truly Orthodox, sharing in the Catholic and Apostolic faith despite nearly 1,500 years of schism. Others will ask: How is this possible? Were the Fathers wrong? How can anyone maintain the true faith without accepting all the Councils? These are all legitimate questions, but they must be thoroughly examined, and not dismissed or treated as though they were already resolved, if we want to heal the schism.

To understand the theological breach that opened in the fifth century, we must start in the year 431. Priests in Constantinople had begun teaching that the Jesus born to the Virgin Mary was not the eternal Word of God, and their bishop, Nestorius, was not correcting them. When he was called out, Nestorius admitted that he believed in a sharp distinction between the divine and human parts of Christ. He couldn’t stand the thought of God being a baby in a manger, or later, dying on a cross. He argued that only the human part of Jesus had had those experiences. This argument led to the Third Ecumenical Council, held in Ephesus, where St. Cyril of Alexandria argued forcefully against Nestorius. The council ended with Nestorius being condemned as a heretic.

In the years after the council, another rift occurred — this time over how to interpret the teachings of St. Cyril of Alexandria (who died in 444). St. Cyril had used the Greek word miaphysis, which meant Jesus had one nature. However, a prominent priest in Constantinople, named Eutyches, began teaching that Jesus’s humanity was swallowed up by His divinity — whereas St. Cyril had taught that Jesus’s humanity and divinity coexisted in distinction, without canceling each other out. A council was called in Chalcedon to resolve this. Eutyches was condemned as a heretic, but there were large portions of the Church that did not care for how

it was done. To Church leaders from Egypt, Syria, Armenia and a few other places, the council’s verdict reeked of Nestorianism — especially because disciples of Nestorius’s mentor, Theodore of Mopsuestia, were vindicated at the council after previously having been censured. Church leaders did formally condemn Theodore, and the heretical writings of his followers that were reinstated at Chalcedon, at the Fifth Ecumenical Council held in Constantinople during the year 553. Unfortunately, this did not prevent the Chalcedonian schism from solidifying shortly thereafter.

Since then, relations between the two sides have been fraught with misunderstandings. For instance, the standard Service for Reception of a non-Chalcedonian asks them to repudiate the heresy of Eutyches — but Eutyches has never been venerated in any of their traditions. In fact, it is recorded in the Acts of the Council of Chalcedon that during the first session, Pope Dioscorus of Alexandria stated, “If Eutyches holds opinions contrary to the doctrines of the Church, he deserves not only punishment but hellfire.” Dioscorus did eventually leave the council out of frustration and was summoned to return but did not. Therefore, in a later session he was deposed from his office as Patriarch of Alexandria. He was not in any way condemned for heresy at Chalcedon. Oriental Orthodox venerate Dioscorus as a saint and consider his deposition to be invalid. In other versions of the Reception for nonChalcedonians, they are asked to repudiate Theodore of Mopsuestia, who they anathematized long before we did. This makes it even clearer that there was not only an initial misunderstanding, but continued misinformation has made it persist through the centuries.

At seminary, we hear a reading from the Lives of the Saints at Matins. During my first year, on the feast day of St. Maximus the Confessor, the reading went into detail about the issues of Chalcedon because of the lingering heresies in the days of Maximus. The text wrongly stated that Dioscorus had been the originator of the Monophysite heresy, teaching that Christ’s humanity had been swallowed up by His divinity! This, of course, was the teaching of Eutyches and not Dioscorus.

We have a strong contingent of Oriental Orthodox students at St. Vladimir’s and, ordinarily, they worship independently in a chapel they’ve set up in a spare classroom. But that morning, one of the Coptic students happened to be in our chapel instead, and so I apologized to him. He said, “I wouldn’t have even been bothered if it had said Dioscorus was a heretic, because I understand that’s how he has been received in your tradition—but it attributed something to him that he never taught.” Oddly, I remember that this most recent year that same reading came up, and this time the text properly stated “Eutyches” but otherwise it read pretty much the same.

To be sure, we Chalcedonians were not the only ones with misinformation. Regarding the bishops at Chalcedon, the Coptic reading for the feast day of Dioscorus claims: “They signed the document of the belief that Christ has two distinct and separate natures.” We obviously know that this is not what Chalcedon taught, but this is how the Oriental Orthodox understood it at the time, and how some still do. There is an Egyptian film called “Crown of the Syrians,” which is about Severus of Antioch, a sixth-century Patriarch of Antioch who essentially solidified the Chalcedonian schism. Severus is a saint to the Oriental Orthodox, whereas we have written anathemas against him. The film is in Arabic, but assuming that the subtitles are correct, what Severus in the film describes is perfectly Chalcedonian theology — and yet the Chalcedonians in the film teach very sharp Nestorianism. Clearly, this is an example of how misunderstandings persist in some circles. However, it also demonstrates that non-Chalcedonians do in fact believe the same things as we do — even if not everyone on either side has come to see it that way.

With all of this in mind, what then is there to do? Thankfully, this dialogue is not just a product of modern-day “ecumenism,” but in fact stretches back quite far. St. Isaac the Syrian is said to have had a good relationship with the non-Chalcedonians back in the seventh century, even counseling others to not focus so much on debate with them. He is venerated in some of their jurisdictions, even though he was not canonically part of their group. St. John of Damascus wrote some decades later that the so-called “Monophysites” were “Orthodox in every single other way.” That continues to hold true today. Several canonized saints of the Oriental Orthodox churches, such as the twelfth-century Nersess Shnorhali of the Armenian Church, and thirteenthcentury Gregory bar Hebraeus of the Syriac Church, affirmed that Chalcedonian Christians shared the same beliefs but were just using different terminology. During his travels as an archimandrite, the nineteenth-century Russian bishop Porphyry Uspensky met with various Oriental Orthodox clergy, determining that they were not heretics after all either.

It was in this same spirit that the Orthodox Joint Commission concluded its July 1967 meeting in Bristol, England, with the following statement:

Ever since the fifth century, we have used different formulae to confess our common faith in the One Lord Jesus Christ, perfect God and perfect man. Some of us affirm two natures, wills, and energies hypostatically united in the One Lord Jesus Christ. Some of us affirm one united divine-human nature, will, and energy in the same Christ. But both sides speak of a union without confusion, without change, without division, without separation. The four adverbs belong to our common tradition. Both affirm the dynamic permanence of the Godhead and the manhood, with all their natural properties and faculties, in the one Christ. Those who speak in terms of “two” do not thereby divide or separate. Those who speak in terms of “one” do not thereby commingle or confuse. The “without division, without separation” of those who say “two,” and the “without change, without confusion” of those who say “one” need to be specially underlined, in order that we may understand each other.

Of course, some Christians on both sides remain skeptical that a schism which has lasted for almost a

Fourth Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon

(1876) Vasily Surikov State Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation

millennium and a half could have been caused only by semantic, linguistic, or philosophical misunderstandings. However, it is evident that both sides have either misunderstood each other or intentionally misrepresented the other at many turns. The way forward is not only to celebrate the vast amount of doctrinal teaching we have in common, but also to talk about the difficult and painful things that continue to separate us. This also includes owning up to the erroneous statements each side has made about the other and facing them in light of what we currently know—while respecting the situation and context in which all of our forefathers found themselves.

STEFAN JOHANNSON is a recent graduate of St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary, where he is finishing non-degree studies in pastoral work. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic he has been assisting a priest in the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia with homechapel services near the southern tip of Maine, in hopes of starting a mission.