9 minute read

You Are Here

YOU ARE HERE ART

Advertisement

PLAYBACK

ST. LOUIS

32

American Art of the 1980s: Selections From the Broad Collections Washington University Gallery of Art January 23–April 18

Visiting the current exhibition at Washington University’s Gallery of Art, American Art of the 1980, was like going to church. Well, not like sitting in a pew and singing some hymns, but rather backpacking through Europe or Mexico and marveling your way through their seemingly endless parade of magnificent Gothic cathedrals. Granted, the gallery was a little smaller than most cathedrals (it only took me about 20 minutes to go through) and the art students cruising in and out were a far cry from any clergy or devotee I’ve seen. But the work at the gallery, mainly towering paintings bursting forth with that renewed interest in colossal figure painting of the 1980s, encouraged the viewer to behave the same way he or she would have in any of those cathedrals: shuffling sideways, being careful not to disturb the quiet devotion and meditation such a place surely deserves, craning your neck to look up and around, standing and gawking in front of each work, maybe not quite sure what was so moving about each one, but unable to walk by without being affected.

Like traveling pilgrims of the Fourteenth Century reading about the Passions of Christ in stained glass or gold-leaf and tempera, at Wash U I was presented with the passions of the 1980s—materialism, celebrity, commercialization—through the iconography blaring forth from work such as Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Horn Players, David Salle’s Pound Notes, and Keith Haring’s Red Room.

Every work in the exhibit seemed to deserve that same sort of reflection. Robert Longo’s Untitled from the White Riot Series reminded one of a classical frieze transplanted from the Acropolis, while Jeff Koons’ Louis XIV mirrored its overindulgent Rococo origins while its glittering metallic surface brought the viewer sharply back into the present age.

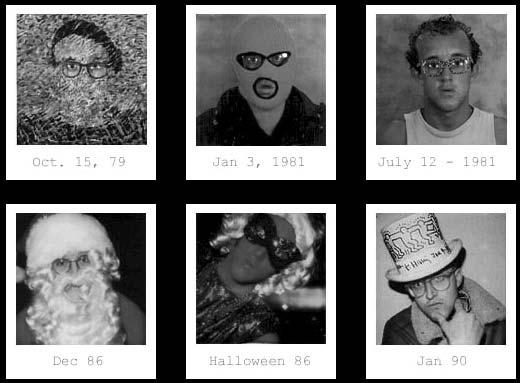

Top left: Jean-Michel Basquiat; top right: Keith Haring (in a self-portrait Polaroid series documenting himself through the ’80s)

Of course, by removing these pieces from their historical context, we’re encouraged to forget about what happened to the art world during the ’80s. The exhibition catalog tried to remind me of the impact that the “media- and imagesaturated era” had on these artists and that artwork of the 1980s was seen as a conspicuous consumer good but, while blamed for reducing the artist to a mere “producer,” also revealed a rebirth of art as a personal exploration.

I think, though, I ignored that reminder and chose instead to revel in the near spiritualness of this work. Maybe it was comforting for me to find work that was powerful and full of strength in a “traditional” form as opposed to the new media work flooding the art scene these days. After all, any artwork viewed within an isolated context is bound to be misinterpreted. Still, who thinks about such things in church? I was too busy browsing the Sunday school schedule. —Joshua Cox

Time Play: A 25-Year Retrospective of Van McElwee’s Video Art Saint Louis University Museum of Art January 23–April 4

Relatively speaking, video art is a new art form. Compared to its millennia-old siblings, sculpture and painting, it’s just a kid. Hasn’t achieved the respect that comes with adulthood. But in the family of art history, it could more accurately be seen as on the cusp of adolescence; all the awkward physical changes, the moody swings between cocky certainty and self-conscious, defensive demands to be taken seriously. Young enough to be hip, but not old enough to vote.

Into this brave new arena, Van McElwee has cast his shadow. The SLU Museum of Art is currently showing a retrospective of his work that ranges from 1978 through 2003. Twentyfive years creates a long shadow, and McElwee has not been idle during that time. The exhibit includes single-channel videos, multiple-screen installations, stills, prints, jigsaw puzzles, lenticular prints (aka Blinkies), and an interactive computer piece. Viewing the exhibit and experiencing the range of emotions it elicits is not unlike going through the carnival ride of puberty itself. The cacophony of sounds and sights, the hyperawareness of tiny details, the speeding up and slowing down of time, the sense of spiritual oneness with the world, as well as the feeling of singularity and isolation—McElwee’s work captures all the conflicting moments of that slow catharsis out of childhood.

After 25 years of continual work, his oeuvre is a large serving of art—more than can be easily swallowed at one sitting. After two trips to SLUMA on Lindell Boulevard, first impressions had enough time to gel into observations, with the conclusion that his less complex pieces are easier to appreciate simply because they don’t cause indigestion. The hyperactive editing of images and sounds in Confluence (1999) creates the dissonance of a bad dream. Granted, it’s an important work, the winner of several awards, including Grand Prize at the NAP Biennial. Notice that “important” and “enjoyable” are usually not interchangeable. With nanosecond cuts from scenes that range from an Indian funeral to a carnival, a Cairo market to rush-hour Tokyo, the waves of movement become felt as well as seen. The normal senses of time and place have been usurped by overlapping clips of foreign situations—“foreign” because we are not invited into these events. The carnival is not fun, the funeral for a stranger does not bring grief or sadness, and after a few minutes, the grasp of “reality” that one expects to hold seems to flicker like snow on a screen. This piece and one titled Radio Island (1997) create such disjointed visual flows that it is impossible to mentally articulate what one is experiencing.

On the other end of the spectrum, McElwee has produced works that offer enough breathing room to allow exploration of the art. One such work was Equilibrium (2000). Two screens, side by side, show the same loop, one set in forward time, one set in reverse. A wrecking machine, looking for all the world like a horse grazing, chews huge mouthfuls of steel and cement from a building. As one building is destroyed, the

March 2004

From the Confluence video installation by Van McElwee

building on the other screen ascends into existence, being spit out from the horse’s mouth. It would make a great creation myth. These horses are beautiful: their necks curve so gracefully, the muscles tensing and flexing as they turn to nibble another sprig of wire.

Sound and syncopation are vital elements in McElwee’s program. Split Second #1 & #2 (2001) are video stills screened onto jigsaw puzzles. Seems like a relatively simple piece, but in McElwee’s world nothing is simple. The stills are split-framed into four parts, and while one contemplates the surreal colors and David Lynch distortion of the beheaded human with folded arms, a doorbell rings, and somewhere an airplane revs its engines in preparation for takeoff, while a staticky, burnt electric buzz marks a series of unlucky insects. These sounds are not actually part of this piece, but as audio images from adjacent works, they become associated with the experience of looking at the stills.

In many of his works, McElwee focuses on architecture: man’s relationships to buildings, human constructions in contrast with nature, interiors melting into exteriors, etc. In the screening room where seven videos play consecutively, five of the works use architecture as the basis for the electronic structure. He travels to far corners in order to utilize cutting-edge structures for his own modes of expression.

The artist is most often quoted for his statement, “I want the work to be something, not just about something.” If this is his ultimate goal, he has succeeded. McElwee’s videos are not viewed so much as experienced. The repeated images, constantly changing, become embedded in the memory like a visual mantra. The work becomes more than the clever manipulation of a modern medium. The sense of time and spaces melting together is merely the tip of the existential iceberg. After reading T.L. Reid’s interview with McElwee from the journal After Image, it’s clear that this man combines science, technology, and art in ways that are beyond my ken. At one point, he talks about a Dutch computer-designed building that becomes a starting point for one of his videos: “This building was born in a computer. In my piece, it will jump again into video where it can mutate freely. Particles will be changed back into pixels, matter into light. The building will be melted, frozen, pulverized, and melted again into something new and totally transmissible.”

The artist is brilliant, he’s discreetly living in town working as Professor of Media at Webster University, and suddenly it seems that the vitality of St. Louis art is a bit brighter. —Rudy Zapf

Polly Apfelbaum: Crazy Love, Love Crazy Contemporary Art Museum, January 23–March 28

For me, visiting Polly Apfelbaum’s exhibit at the Contemporary, Crazy Love, Love Crazy, was less about the artwork (too much of a decoration to be that impressive) and more about never wanting to leave that great building while trying to give off the cool vibe of not caring about it.

From the moment I entered, my sneakers echoing metaphorically off the concrete floor, walls, ceiling, reception desk, and practically every other surface, I knew that I was entering a realm of cool—not pretentious cool, not trendy cool, just…cool. And I wanted to be a part of it. After enough time in their galleries, I began to dream that maybe the gallery attendants weren’t just making sure I didn’t step on anything, but were eying me for a job there or at least an invite to their cool dinner party.

Don’t get me wrong: Apfelbaum’s work wasn’t entirely without merit. It was rather visually stunning, I’m just not sure I understood what it was supposed to be about. The installation was designed especially for the Contemporary, and the impact it had within that environment was significant. Almost like a surreal swimming pool, Apfelbaum’s blanket of cut velvet flowers had the effect of softening the somber gray interior and fighting for my eye’s attention against the soaring gallery ceilings. The “Cool” side of the exhibit had even more impact since it didn’t have the outside distractions from the windows on the “Warm” side.

The accompanying literature contrasted Crazy Love, Love Crazy with the structurally and blatantly masculine installations of artists such as Carl Andre and Richard Serra who use “heavy, industrial materials” for their oppressive work while Apfelbaum constructs her “superficially happy” installations with ultra-feminine hand-cut flowers. Well, sure, that much is obvious, but who has time to think about such things while you’re trying hard not to pick or scratch at some part of yourself since you’re the only visitor and all of those cool people are looking at you?

Still, there is something to be said about the effect of Apfelbaum’s “icons of femininity” on the coolly masculine walls of the Contemporary. What’s it say about me that I wouldn’t have expected a (straight) man to create this? Am I such a blatant product of my sexist, racist, and xenophobic society? All I know is that for the time that I spent in front of Crazy Love, Love Crazy, I wasn’t thinking about any of this. Rather, I was thinking about checking the job listings at the Contemporary as soon as I got home. —Joshua Cox

33