issue #15

Boneshaker: Real Cycling

Except this isn’t real, of course, it’s digital. To get your hands on a real Boneshaker, to feel it and smell it and hide it in your pannier, go here. We make other great bike stuff too, especially bicycle art prints. Check them out here. And to let your ears take your mind on a journey, there’s our new podcast series.

For kicks. For adventure. For the soul.

The reasons we ride are as varied as the places we ride through. Thousands of miles are covered in the next hundred pages: our brave writers journey underground and back in time, through America, across the Balkans, over the Alps and the Himalayas and on around the world. Twice. But for all these vast distances, the greatest journey they each make is in the mind, as the wheels spin, the heart expands and the self unwinds to a distant horizon...

Welcome to issue #15

contributors

words marko S ˆajn, jude brosnan, julian sayarer, zoe howes-wiles, marc simper-allen, mike white, matt cook, dave gill, raphael krome, alex throssell, simon lay, scribbletribe studios, chris lanaway, tony haupt, jet mcdonald, pi manson

photographs marko S ˆajn, ty snaden, colin flash tonks, joff summerfield, lucas brunelle, benny zenga, duncan elliott, chris sleath, dave gill, raphael krome, simon lay, chris lanaway, tony haupt

illustrations ... paul heredia, re-robot studio, chris sleath, casmic lab, gill chantler, samuel james hunt, chris thornley, eleanor shakespeare

layouts joanna buczek, luke francis, chris woodward, max randall, jordan carr, molly cockroft, jack sadler, sam edwards, ben hamilton, katie mitchell, ali campbell

backpats and handclaps

john coe, matt at bristol dropouts, peter whitehead, the bristolian café’s mega breakfasts, kai at offscreen, rob, ryan & the roll for the soul crew, benjy johnstone, james perrott for his unwavering business guruship, tor mcintosh, benny zenga, nick hand at the letterpress collective, rik at ripe digital, matt farah at williams research center, tommy godwin, anny mortada, penny morris, muriel at swrve, our fellow bipsters, oliver norcott, phil hambley at scribbletribe studios, sadie ruth campbell, cass gilbert, suresh ariaratnam, and the unflappable support of ian and the crew at taylor brothers. no thanks at all to betsy the keyboard-trampling cat

copyrights & disclaimers

The articles published reflect the opinions of their respective authors and are not necessarily those of the publishers and editorial team. © 2014 Boneshaker. At present, we are committed to remaining free from advertisements & advertorial.

contents

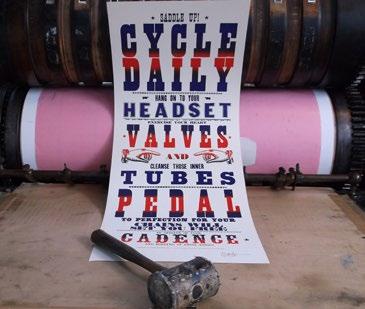

Printed in Bristol by Taylor Brothers (taylorbros.uk.com) on FSC ® certified paper. Boneshaker is extremely proud to be part of Bristol Independent Publishers (wearebip.co.uk) conceived by james lucas & john coe / compiled, edited and brought to life by jimmy ell & mike white / lead designers luke francis ( talktofrancis.com ) & chris woodward (chriswoodwarddesign.co.uk) / cover image by chris thornley (raid71.com) / opening illustration (opposite) by re-robot studio (re-robot.com)

tommy godwin, the long distance legend 4 the ups & downs of a year-long bicycle tour 8 bikes & beetles 16 electric pedals 18 life cycles 22 that pipe! 28 in for a penny 36 a space the eye cannot see 42 the papergirl 48 dream maker 52 artbreak 56 press on 58 the classics experience 64 the old and the new 70 the transalp 76 balkan ride 80 steel yourself 86 the first trip 92

Tommy Godwin’s record-breaking 1939 ride is a feat of physical and mental endurance so momentous, so outrageous, that it’s difficult to fully comprehend what the achievement actually represents.

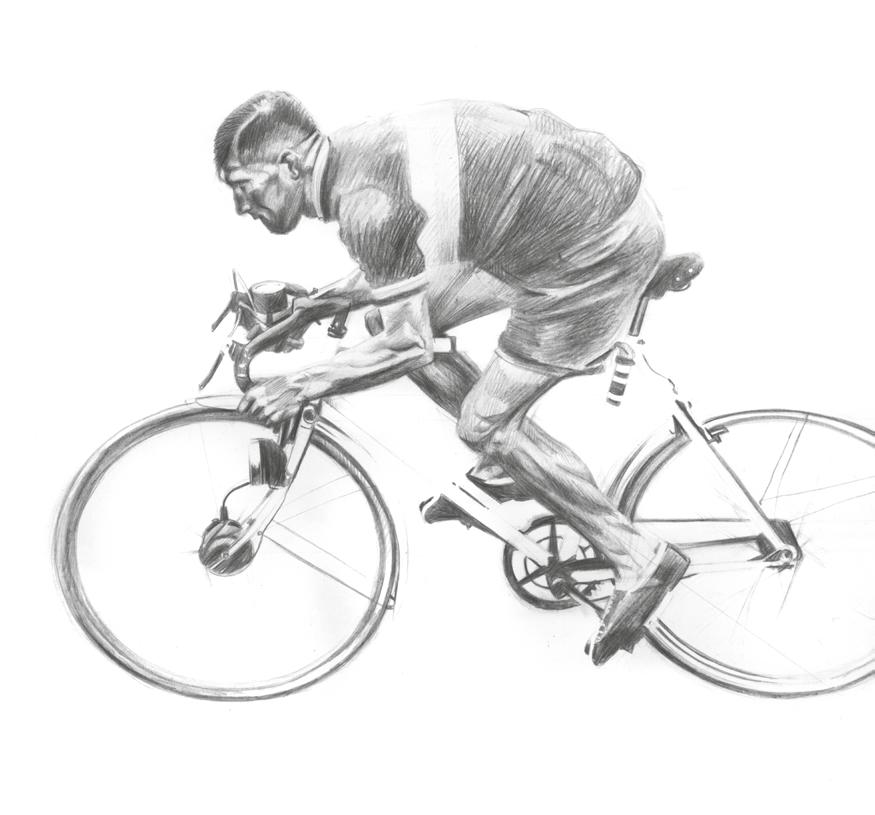

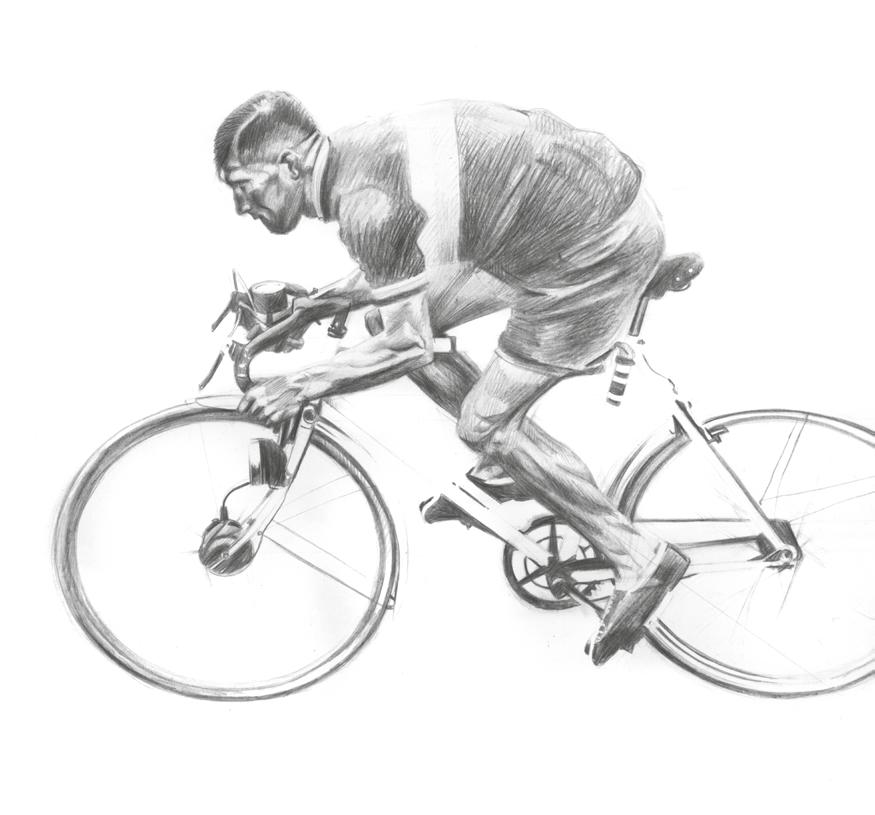

Illustrations by Samuel James Hunt

Illustrations by Samuel James Hunt

TOMMY GODWIN THE LONG DISTANCE LEGEND

Perhaps the greatest endurance feat of all time, and one of the least well-known and celebrated, Tommy Godwin’s record-breaking 1939 ride is a feat of physical and mental endurance so momentous, so outrageous, that it’s difficult to fully comprehend what the achievement actually represents.

If you are not a regular cyclist, but particularly if you are, consider this scenario: you wake before the dawn and drag yourself from your bed and out into the bleak morning of a Boxing Day in wartime England.

You eat little (if anything) for breakfast and ride purposefully through the inclement weather and along poorly maintained streets. Your bike is wellmaintained, but is a heavy steel-framed machine with only four gears. You ride for some hours, and then you ride for many more – until you have completed a shattering 185 miles on the road.

The next day you ride 204 miles.

You don’t think that this is particularly extraordinary; in fact it’s actually a little below your daily average, and after all you have been doing this for over fifty-one weeks straight, with only one day off!

In four days’ time you have good reason to cheer the arrival of the New Year – your name is Tommy Godwin – and you have just smashed the record for most miles cycled in a year.

In a modern age of millionaire golfers and petulant footballers, Tommy’s achievement serves as a

useful reminder of what true sporting prowess was, and can still be. Tommy was described by his family as the most unassuming, gentle man, but he quietly proved that he was as hard as iron physically.

Known to friends and family simply as ‘Tommy’, Thomas Edward Godwin was born in Fenton, Stoke-on-Trent on the 5th of June 1912. At the time children grew up quickly, were often raised in hardship and were expected to work from an early age. Tommy was no exception, and took a job as a delivery boy aged twelve, which helped him to pull his weight and share the burden of providing for a family of twelve.

A requisite (and most likely to young Tommy a perk) of the job, Tommy was equipped with a heavy bike with which to complete his daily deliveries on behalf of the owner of a general store, newsagents and butchers. Tommy enjoyed riding the bike as part of his rounds, and an interest in cycling sparked to life.

A few years later, the then fourteen-year-old Tommy would be inspired by an advert asking for participants in a local 25-mile time trial.

Legend has it that Tommy hacked off the heavy steel delivery basket from the front of his bike, and kitted out with both borrowed shoes and wheels proceeded to steam around the course in a winning time of one hour and five minutes.

Still at a tender age, the initial spark had already exploded into a full blown love affair with cycling.

7

He joined various cycling clubs, won races, and began to amass an array of over 200 medals and trophies, and by 1937 his confidence was such that he decided to challenge the ‘year record’, a record recently won by the Australian pro-rider Oserick ‘Ossie’ Nicholson.

Tommy succeeded in persuading his employer to sponsor him, and at 5am on New Year’s Day 1939, after months of physical and mental preparation, vegetarian, tee-totalling, 26-year-old Tommy pushed off, and pedalled the first mile of a journey that ultimately would not end until a further 500 days, and 99,999 miles had been completed.

Tommy’s plan to win the coveted year-record was simple but brutal; he aimed to cycle 200 miles a day, broken down into 4 x 50 mile ‘chunks’ allowing time for food and rest.

On the longest day of the year, 21st June 1939, Tommy rode a total of 361 miles. Had he watched the summer-solstice sunrise over Stonehenge, at the end of the day he could have been sitting down to supper in Paris.

By October 26th, Tommy had achieved what he had set out to do, and much, much more. The year record had not only been won, but with 66 days to spare, he had time enough to smash the previous record – and put it beyond reach for all others who would valiantly try, yet fail for many years to come. Even after Tommy had completed the year-record challenge on 31st December, he didn’t just hang up his cycling shoes and take it easy in 1940. Just the opposite, he carried on riding huge mileages until mid-May.

Tommy, not entirely satisfied with the greatest year-ride of all time, wanted to push on further to gain a secondary record of the fastest completion of 100,000 miles! René Menzies, a previous holder of the year-record, had set the 100,000 mile target at an impressive 532 days.

By this time the restrictions imposed by an escalation of World War II were starting to make problems for Tommy. Besides the threat of a callup to serve his country, Tommy was also hampered by severe penalties for failing to abide to blackout restrictions and by dwindling food supplies. Nutrition bars and gel sachets weren’t an option for Tommy. His diet was very simple: bread, milk, eggs, cheese – and even these became scarce as rationing began.

Tommy rode two bikes during the course of his record-breaking ride. The first, a ‘Ley TG Special’ was custom built at the request of Tommy’s employer and sponsor, Mr A. T. Ley. The frame was built with Reynolds 531 tubing with high pressure 27" Dunlop tyres, a Brooks saddle, Solite front hub and (initially) a Sturmey-Archer three-speed hub gear.

The bike rode well and had been put together with durability in mind. However, huge mileages and poor road conditions would lead to excessive wear on the bike, and the costs of spare parts and bike maintenance ultimately became too much of a burden for Ley Cycles to bear.

Arrangements were made for a new sponsor to step in to support Tommy’s record-attempt, and it was

8

In a modern age of millionaire golfers and petulant footballers, Tommy’s achievement serves as a useful reminder of what true sporting prowess was, and can still be.

the Raleigh Cycle Company that were most keen to be involved.

Tommy’s new bike would be a Raleigh Record Ace. A four-speed medium-ratio Sturmey-Archer hub gear, which had been fitted to the Ley TG Special in March, was brought over to the new bike for continued use.

Although the Raleigh was cutting-edge technology at the time, it was still a 14kg-ish bike – compare that to the 2kg frameset of a top-end modern bike like the Specialized S-Works + McLaren Venge.

Besides the differences between Tommy’s bike and modern machines, Tommy also didn’t have the benefits that professional riders have today with regards to clothing, accessories and personal maintenance. Lycra, breathable man-made fibres and lightweight waterproofs were not an option in 1939. Tommy would wear thick tights and heavy woollen clothing that would often be wringing wet at the end of a day’s ride. Endless days in the saddle were taking their toll and Tommy suffered from saddle soreness. After limited success using ointment to relieve his suffering, on the advice of a female cyclist he donned a pair of ladies silk undies and greatly reduced his discomfort!

The pressure increased further on Tommy and his quest to gain the 100,000 mile record. The UK had experienced a particularly harsh winter at the start of 1940, and the roads were treacherous, with huge amounts of ice and snow covering the country.

Tommy had a terrible time in the freezing conditions, often skidding and falling from his bike. Damage to the bike, and also to himself, were all too common and simply had to be endured.

Eventually the winter broke and Tommy had the chance to pile on the miles. He was back on track to beat Menzies’ record. On May 13th, 1940, Tommy rode into Paddington Recreation Ground Track; at long last, he had the finish line firmly in sight.

Watched by his sponsors, cycling friends and other dignitaries, Tommy rode the final mile of a legendary journey. Tommy had bagged yet another

emphatic victory. Perhaps as an effort to help make the statisticians’ and sports writers’ jobs easier, he had covered the 100,000 miles in 500 days straight; a simple sum to work out that he had averaged 200 miles a day.

Tommy was called up to the RAF very soon after the end of his record-breaking ride. No chance to rest, or to reap the deserved publicity or financial rewards of his achievement; it was a tough break.

After the war, Tommy wanted only to return to cycling – and to race once again as an amateur. However, despite the best efforts of Tommy and his friends (several hundred of whom had signed a petition on Tommy’s behalf), he was unable to do so; the cycling governing bodies having ruled that once he had ridden as a professional he would be forever barred from amateur status.

Putting this huge disappointment behind him, Tommy concentrated his efforts on coaching and helping others. He became team trainer to the Stone Wheelers and was a huge supporter of the club throughout his life.

In 1975, aged 63, Tommy died while returning home from a ride with friends to Tutbury Castle. It seems fitting that Tommy’s last day on earth would be doing what he had loved doing all his life: riding a bike.

Tommy Godwin rode further in one year than anyone else in history. He is still the ‘Year Record’ holder and the record will remain his in perpetuity.

After hearing about Tommy Godwin at the Spin LDN cycle show, Boneshaker went home and found the excellent website tommygodwin.com designed by Phil Hambley and the team at Scribbletribe Studios. It’s from this site that the above text and photos have been taken, with kind permission. scribbletribe.com

Tommy Godwin’s story is told in detail in the book ‘Unsurpassed’ by Godfrey Barlow.

9

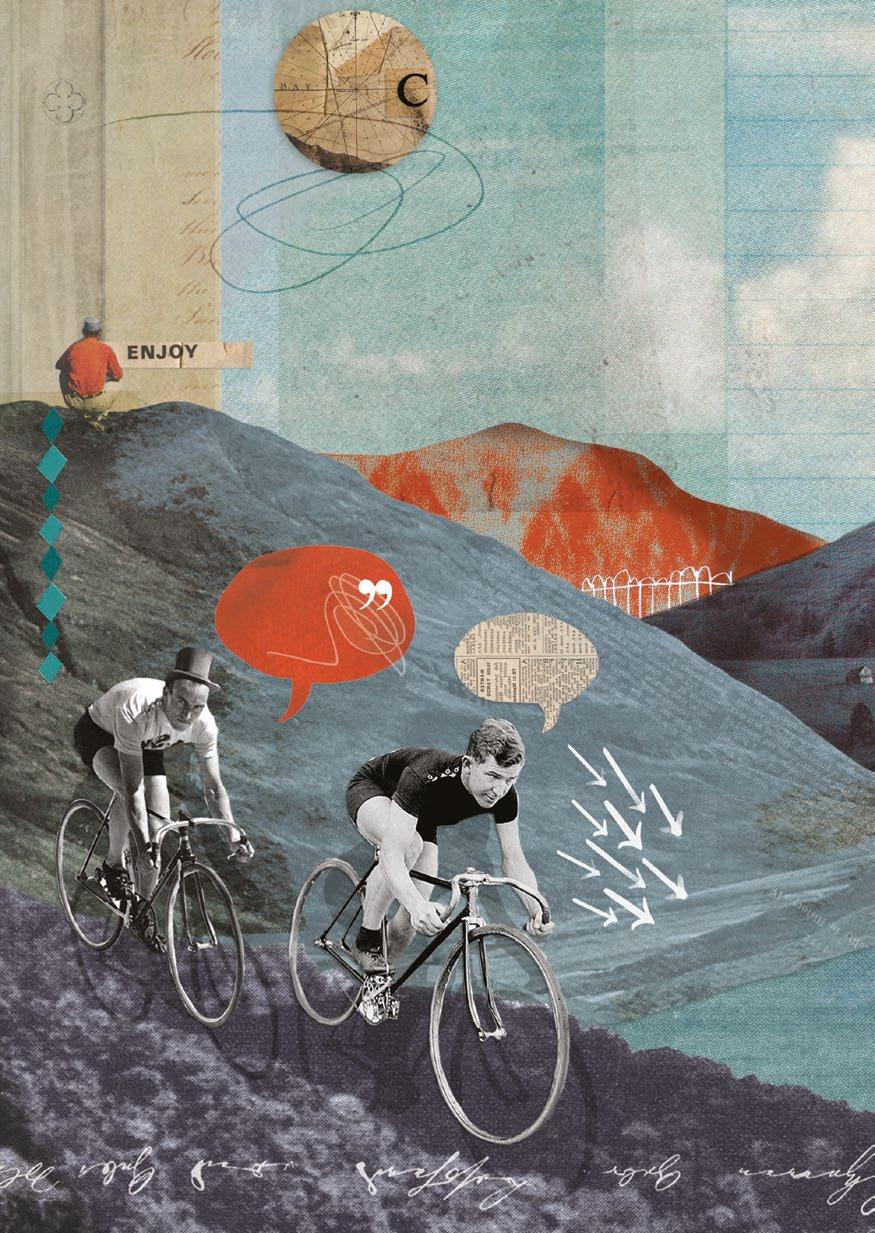

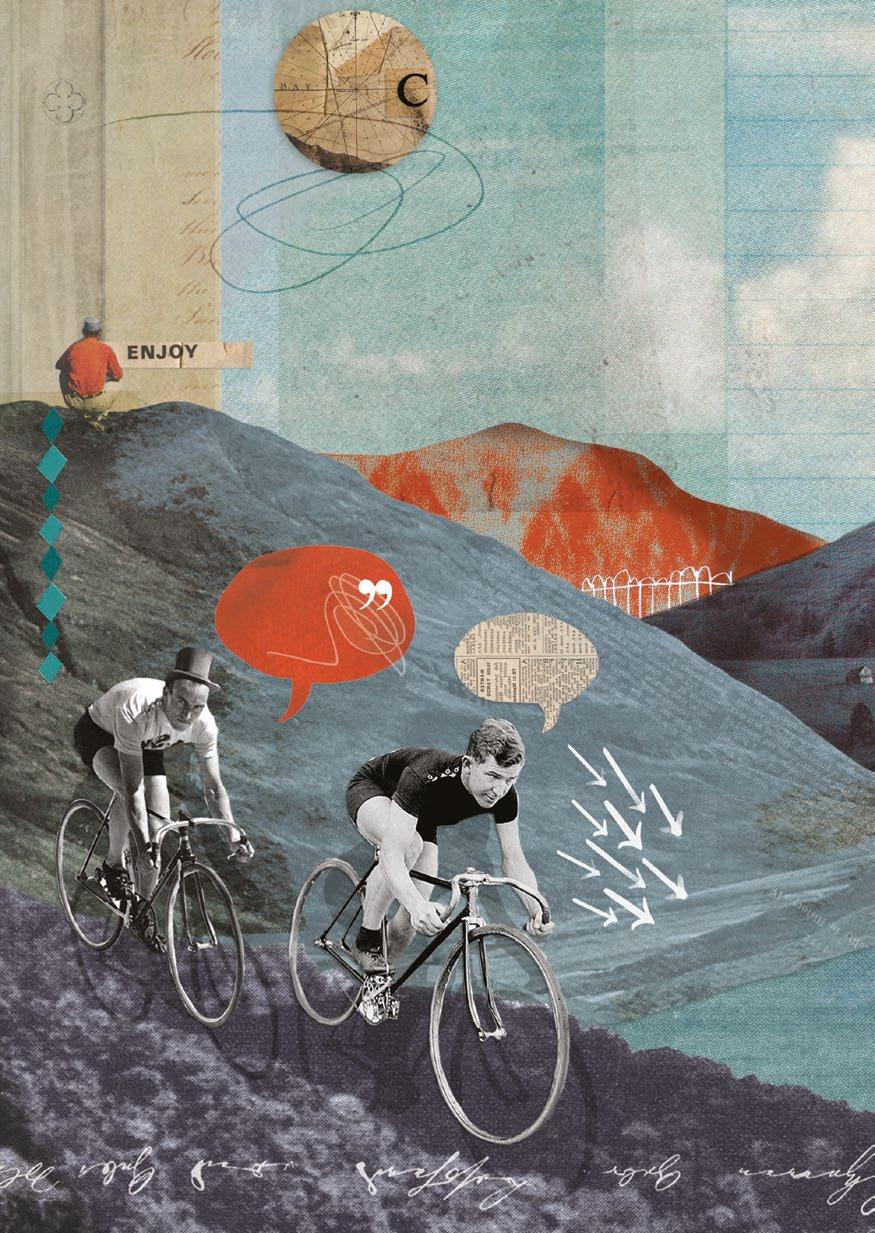

THE UPS & DOWNS OF A YEAR-LONG BICYCLE TOUR

WORDS & PICTURES BY DAVE GILL / VAGUEDIRECTION.COM

It was the end of spring, and it was another day at the office. A drag. A chore. A career path that I didn’t believe in. Later, I’d realise that this was the day that shifted my direction. It was the lightbulb moment, when I decided to quit, fly to New York and set off on a year long, 12,000 mile cycle touring adventure.

There were too many questions going on in my mind to stay, and my eyes would drift to the window with every spare moment. Why am I here when there are so many adventures to be had out there? I looked out, imagining travelling a long way by bike, using the imaginary ride to break the monotony.

It typically goes: newly independent men and women step into ‘the real world’, climb onto a career ladder and make upward steps, hoping to make their mark. They find partners, buy a home, have children and earn enough money to be comfortable. Fine, but why? Are those really the milestones that life should be based around? If they are, then awesome. But these don’t strike me as unreasonable questions to ask, considering our lives get shorter every day. Don’t we owe it to ourselves to explore the answers?

What I’d been seeing every day recently were the glazed-over eyes of people walking down the street who had either learnt that this model was the right one, or had just accepted it without question. I’m not convinced, even though part of me wishes I was. To me, they were drones, robots, automated capturedlives dedicated to a fantasy of contentment and a wish for fullness that might never come. My fear is

waking up as an elderly man and having a moment of realisation: as pleasant as life may have been, I’d lived a life that someone else had prescribed. It didn’t belong to me because I didn’t choose it, or even question it. I was just another old dude who’d taken part in a lifetime performance because that’s what we do. If I didn’t take action, I was on track to nonachieve the same fate. Suddenly a year living on a bicycle seemed like the most sensible thing to do.

I was in my early twenties, and as overly dramatic as it may sound, there’s something about hitting that age. It’s really the first time you realise that mortality is waiting for us all on (hopefully) a distant horizon. It’s oddly quantifiable - with good fortune we probably have around two-thirds of our lives left. But where did the first third even go? Wherever it went, it went fast. This isn’t a dilemma about death, it’s a dilemma about life and what to do with the single chance we’ve got.

Two months later, I packed up the used Trek that I’d found for a bargain price on eBay and set off with no idea what to expect. My panniers were full of unknown. No prior experience. No training. It was probably a bit foolish really. It was November 2012 when I landed in New York City from England, and it was the start of an unusual year. It was the learning that happened throughout the journey that surprised me the most. Learning about this type of lifestyle, about cycling, about the perils and the kindness that frequent being on the road, about people from all walks of life, about myself. The first few weeks on the road were a bizarre mix of hard and easy.

11

Physically it was hard, but I’d been expecting that. My view up until the first American pedal strokes had been that the journey in itself would act as training. It was going to be so long anyway, that prior training may have just put me off the idea completely. Prior to day one, I’d never cycled more than ten miles, and suddenly here I was riding all day. 58 miles. 81 miles. 63 miles. 47 miles. I couldn’t remember being more sore and in pain than those first weeks. The mental game during that time, though, was easy; constantly upbeat, happy about such a change, excited to be out putting in long hours in the fresh air day after day.

Gradually, the mental and physical parts shifted. Physically, my body adapted. The once horrendously uncomfortable leather saddle became pleasant. Legs grew stronger, muscles became less sore, and it quickly became easy to cover long distances. Mentally though, there was a reverse.

It became a roller-coaster ride of emotion: happiness, depression, anxiety, confidence, disbelief, excitement, joy. The entire emotion-portfolio, but lacking any kind of consistency.

It was around eight weeks into the trip when the first wave of negativity hit. Intense lightning storms meant that I was sitting it out, just waiting, relegated to a small tent on a plot of wet grass next to a train station in rural Louisiana. It’s the isolation that does it, that really gets to you. I began to severely miss family, friends, non-temporary human connection, a fixed base. I sat out the three-day storm away from any other people, without a phone signal or internet. Just the intense noise of rain on canvas, the knowledge that my bike was probably getting soaked, and a pot of bland pasta. It might not sound like much, in fact to some people maybe it sounds quite idyllic, but 72 hours without any form of communication with anybody else was enough time for the dark questions to emerge. Was it fair to leave for so long? To just up sticks and leave for a bike ride?

After a while, this negativity turned back to the reason I was here. For positivity and change; for growth; because I wasn’t happy. The roller-coaster went from low to

high, just like a decent one should. Enough time went by to adjust to the lifestyle shock, develop efficient methods of getting by and keeping things dry, and to master the temperamental ride that is bicycle travel.

The journey took me up hills that made me curse in Texas, and down the same hills that made me scream with joy, across green chilli farmland in New Mexico and through rare snow storms in the Arizona desert. Frozen water bottles one day, sweaty t-shirt the next. No new day was the same as the one before. Each had new people, new places, new experiences.

The great days on the bike were truly that. I’d wake up to a sunrise by a lake or next to a mountain, take it all in and then set off for somewhere unfamiliar. Big long days that just click. There’s a rhythm that’s created by pedalling and a flow that happens whilst seeing the world pass by under your own steam. I switched off and the hours flew by, a meditative state like I’d never felt before, all because of cycle touring. It was like an inner switch that took a few hours to reach, but once turned on, an intense clarity would come over me. I was more relaxed, and more present, than I’d ever felt before. This felt like living.

12

Following five months of pedalling down, across and up the United States, I’d arrived in Stinson Beach, Northern California. The previous night, after cycling by bike-light, I’d rolled into the town and in the darkness had stumbled around to find a stealth-camp spot in a State Park by the beach. A remote sandy beach overlooking the Pacific. This was one of the best parts to living on a bike –realising the beauty of our planet.

“Get Up! Get Up! You’ve got 5 minutes! You’d better be out of here when I get back!” Maybe it wasn’t such a beautiful moment after all. It was 5:45 am and a blurry figure was kicking the canvas a few inches away from my face. Alright, OK!

The blur turned out to be a park ranger on his morning duties. Oops. In all honesty, this kind of situation wasn’t that uncommon. Stumbling out of the tent, and exhaling the daily sigh of relief when I saw that the bike was still there, I began to pack up and realised that someone else was experiencing a similar morning. Yawning and rubbing his eyes from a lack of quality sleep, Brad had been sleeping on the beach.

Months before setting off, I’d made a decision to split the journey into two. Just going for a big ride wasn’t enough. I wanted to also use the journey to explore contentment and doubt with others.

Along the way, I’d been meeting up with a variety of people to talk about whether they’d experienced the same questions, and to record their answers through film. Did they enjoy their path in life? What would they change and do the same? Some of those encounters were pre-organized, and others happened by chance, but out of all of those meetings, from singing cowgirls to Hollywood directors to hunters, it was meeting Brad that was the most memorable.

We both grabbed our stuff and walked to a nearby basketball court as the sun was rising over the Golden State. He recalled growing up in Boston, where as a teen he was caught dealing drugs and ended up being sentenced to two years in jail. Eighteen months into his sentence, Brad had a bad day, got frustrated by the guards and ended up punching two of them. Because of the fight, he was given another eight years inside. Bringing his total sentence to ten years. A decade.

13

THE ONLY THING TO DO IS DEAL WITH IT, WORK IT OUT AND ACCEPT HELP WHEN OFFERED, BECAUSE DOING SO CAN LEAD TO GREAT, UNEXPECTED THINGS.

14

That’s enough to shock most people, but it was a fraction of the story. As Brad successfully shot hoop after hoop, three pointer after three pointer in the California morning glow, and I constantly missed the basket, he told me about what happened after prison. On his release, he was dropped off in downtown Boston with a $60 cheque. For a moment he looked around, and the best thing he could think of was to go back to prison where his needs were met. The tempting option was to punch a crossing guard and return to what he knew best. Instead, he walked for 15 minutes to clear his head and weigh up his options. And it was in those 15 minutes, whilst walking, that a new plan formed. He’d leave Boston, and walk. He’s walked for 13 years, taking in 38 states and thousands upon thousands of miles.

It was completely by chance that I met Brad and learnt his story, and it made me question fate. Was meeting him an always-meant-to-happen moment? Suddenly, the concerns and questions I’d been wrestling felt valid. Brad had changed his life by setting off. He’d turned his life around. That word, life. So grand, so vague, so many variables. But here was a guy living life, embracing every day. He didn’t have it easy, but he seemed truly happy, and that positivity was contagious. For weeks after that, during the tough times, the times when the hills never ended, or illness kicked in, or the homesickness seemed unbearable, I tried to remember Brad, and I appreciated the days much more then.

But when I arrived in British Columbia a couple of months later, after weeks of cycling into a headwind, another dark part of touring reared its head. Mechanicals. My load was heavy. Clothes, sleeping equipment, stove, food, camera, laptop for editing and writing. So what on earth was I doing with a flimsy 32hole rear rim? Any experienced touring cyclist would’ve called me an idiot. A few actually did. Every day I woke up, cycled for a few hours, and snapped a spoke. Sometimes three.

It’s an easy fix of course - simply a case of getting a decent wheel with a lot of spokes. I should’ve known, it should’ve come up in research, but remember I was inexperienced and foolish going into this.

15

IT’S THE ISOLATION THAT REALLY GETS TO YOU. I BEGAN TO SEVERELY MISS FAMILY, FRIENDS, A FIXED BASE…

I was operating on a minimal budget because of the duration of the journey, so the thought of shelling out a month or more’s food money on a new wheel was something I was pretty keen to avoid. It was a daily disaster that took its toll - I just hoped that the spokes that snapped would be non-drive side so I could replace them on the fly. Eventually it became such an annoyance that I did purchase a new wheel, but not before my rim was an egg-shape and riding became a truly wobbly experience. There were many times that things went wrong on the road. And it took me a long time to realise the benefits when everything goes awry. Often I’d get angry and frustrated and scream to the sky, but then I realised that it’s these moments that count.

When I was on my knees at the side of the road with the bike in pieces, somebody would drive past, stop, and ask what was going on. They’d offer expertise, a hot meal or a place to sleep. It did wonders to restore my previously cynical faith in humanity. Those moments lead to great memories and even greater friendships. Invites into a cabin overlooking a lake with Buddhists, or into the spare room of a Canadian police officer’s home. Nights spent around delicious home-cooked meals which were so refreshing after periods of sustained tent life and a granola diet. Steak! It took mechanicals to help me see that whether it’s a snapped spoke, a broken chain or a run of bad luck in general life, the only thing to do is deal with it, work it out and accept help when offered, because doing so can lead to great, unexpected things.

It’s easy to look back and realise, in hindsight, that the hard times were valuable. In the moment it’s much harder. You’re in it, and hard is hard. The final few months did feel like hard work, sleeping rough, scary roads and insane truck drivers, the ever-approaching winter. Nights spent searching for warmth in abandoned barns to avoid getting snowed on and the slow, frosty mornings that followed.

As New York filled my sights from the final Canadian city of Niagara Falls, I felt hesitant. But not because of any of that; that was bearable. It might not’ve been fun but it was just the way it was.

Instead I was hesitant because it was coming to an end. Life on the move had turned into something I’d learned to cope with. A comfortably uncomfortable lifestyle. The thought of stopping and returning to a life based in one place had grown scary, far more than a thin road shoulder and a logging truck.

The final day, day 368, was an easy one. Miles had long become irrelevant and that afternoon my mind couldn’t have been further away from the act of cycling. It felt bigger than that. All the people, the experiences, the memories. The good and the bad. Internally I was focused on the previous 367 days and what they symbolized. Then, and without really realising it, I pedalled over the George Washington Bridge cycle path and arrived quietly in New York.

The Big Apple, the biggest city in America, was like a metaphorical sledgehammer to the face. My days had been mostly in between towns, quiet and secluded, and here I was where everyone was getting on with it, going about their lives, taking the subway home from the hustle and bustle of the daily grind. It was a shock because it marked the end. The ride was done.

A year of cycling and an overly ambitious goal had come full circle. Initially, because of the culture shock, I felt intensely sad that it was over. But after a few hours of taking it all in, that turned to optimism and a realisation about what the previous year had meant.

Sometimes we have to invest in ourselves and the simple act of pedalling and meeting people was my way of doing that. It brought with it so much learning, the kind that only comes from getting out there and chasing new experiences. I learnt to stop being intimidated and anxious, to turn dreams and ambition to action, to roll with the punches that are given to us, that grit and determination beat skill and experience, and that humans are kind.

They’re priceless lessons learnt from the road that I’ll hold onto forever. Riding a bicycle for a year altered my outlook, shifted my priorities and truly changed my life.

16

THE THOUGHT OF RETURNING TO A LIFE BASED IN ONE PLACE HAD GROWN SCARY, FAR MORE THAN A THIN ROAD SHOULDER AND A LOGGING TRUCK.

17

BEETLES BIKES

WOR DS & PICTURES JUDE BROSNAN / ISPEAKBIKE.BLOGSPOT.CO.UK

PERHAPS

When you go around with a name like ‘Jude’ you get A LOT of Beatles references thrown/sung at you. It’s no wonder I feel an affinity with VW Beetles. I feel like they understand.

I first visited Mexico in 2000 as an excited 18-year-old on a gap year and fell head-over-heels in love with the country. Over the last decade (plus a few years) I’ve been lucky enough to return to Mexico several times. While I was cycling around

Mexico City a year ago, I noticed that there were many more bikes on the road than VW Beetles.

In the 1960s a Volkswagen Beetle factory opened in Mexico and they soon became the country’s standard box car. VW Beetles, or ‘Vochos’ as they are lovingly nicknamed, were a symbol of modernity and Mexico’s economic growth. Green and white Beetles (vocho verdes) even became the official taxi.

What’s interesting is that over the years these cars have begun disappearing while cycling has taken off. As I rode around, I started taking pictures wherever I saw a bike and a Beetle together. The car usually represents modernity while the bike is seen as traditional – these pictures question that perception. Perhaps Mexico’s outnumbered Beetles offer a small glimmer of hope that the future will ride on two wheels...

MEXICO’S OUTNUMBERED BEETLES OFFER A SMALL GLIMMER OF HOPE THAT THE FUTURE WILL RIDE ON TWO WHEELS…

ELECTRIC PEDALS

The dynamic future of community cinema

Images

Words

by Colin Tonks

by Zoe Howes-Wiles

Images

Words

by Colin Tonks

by Zoe Howes-Wiles

The lazy weekend sun is setting over Telegraph Hill, south east London, as the local community flocks to an unusual outdoor screening of Grease. They bring their children and their camping chairs, their vintage glad rags and woolly jumpers, their sparklers, flasks and bottle-openers. And of course, they bring their bikes –for tonight’s screening is powered purely by legs.

The atmosphere is charged. Children play on bikes as Pink Ladies gather, swirling around with champagne flutes and blond curls, unpacking picnic hampers to celebrate the night in style. Couples pedal side-by-side as the T-Birds arrive. In grunge black leather they ready themselves with beers and blankets. Fathers and sons discuss gear-changes as the BBQ smokes-up, the city lights up, cameras flash and movers and shakers dance to Motown. All around, cyclists pedal away on bicycle generators; tonight, they are the stars. They are the batteries generating the electricity to power our Saturday night entertainment. Welcome to Electric Pedals.

Electric Pedals was founded by Colin Flash Tonks as a way of harnessing human power to generate energy from cycling. Since then, the possibilities of bicycle power have radically developed. In Malawi, a young man sets up a backpack cinema in his village, surrounded by fascinated faces. In Berlin, the lights dim in Katie Mitchell’s pedal-powered production of Atmen as the actors momentarily pause to wipe the sweat from their brows. While back in London, it is

break time at Horniman Primary School and in the Radio Station Shed young eco-DJs mix with renewable energy. Electric Pedals has become the forefront of bicycle power innovation.

But it’s more than that, Electric Pedals is about communication. It’s about connecting people. Whether through outdoor entertainment or classroom education, the focus is on community. Electric Pedals’ collaboration with New Cross and Deptford Free Film Festival meant that more than 700 people came together to sing-along to ‘Greased Lightning’ and swoon over John Travolta. As Jacqui Shimidzu, Community Volunteer and Founder of NXDFFF explains, ‘we could have just had a generator powering this outdoor performance, but Electric Pedals brings added value. People don’t quite believe that cinema can be completely powered by themselves; it’s a spectacle.’

The how of cinema is redefining the extent of what cinema can now be. Dynamic and communal, active participation transforms cinema into an immersive and unpredictable performance where escapism becomes a team-effort - a shared experience - rather than the solitary silence of a dark auditorium. As Tonks makes his last directorial adjustments to the 20 bicycles that will power tonight’s screening, he admits the everpresent ‘fear of jeopardy’ in producing this kind of live cinema: ‘It could all still go wrong.’

And it did.

22

Relying solely on constant, real-time pedal power throughout the screening meant that when the human batteries stopped pedalling, the film stopped reeling. Blackout. There was no back-up. With adrenaline surging to resolve the situation, the atmosphere was suitably electrified. The boundaries between picnicking neighbours broke down; red-lipsticked enthusiasts carried on singing regardless, sending a wave of encouragement back to the cyclists with a bawdy rendition of Summer Nights. Suddenly, the screen lit up and the music returned. Cheers rang out for the cyclists; the stars of the show were back on their bikes.

‘This is healthy cinema’, says one Goldsmiths graduate. ‘It’s like a little festival’, says another, ‘There’s a beauty to it’. There is. When something this positive brings people together, there is always beauty - and a world away from South East London, Electric Pedals uses bicycle-powered cinema to bring African communities together in just the same way.

Back in 2009, in association with The Great Apes Film Initiative, Tonks engineered a basic pedalpowered cinema for a hilltop village on the edge of Mgahinga National Park, Uganda, consisting of just two mountain bikes that turned bicycle generators and powered a projector and guitar amp sound system. This conservation project needed to bring greater awareness to the local communities of the endangered mountain gorillas that lived alongside them. Through Electric Pedals’ lightweight and eco-friendly innovation,

even the most remote villages could be educated and entertained through film. For most, Electric Pedals was their first experience of cinema.

Similarly, last year Electric Pedals developed a pedalpowered cinema backpack kit trialled in Malawi. Malawi is 80% rural, and so while film is recognised as a powerful social tool, it is only applicable if it can reach (be carried to) the inaccessible communities. Being able to cross rivers and walk long distances through dense undergrowth, Electric Pedals provided a portable answer with their 20kg backpack cinema. The effect can hardly be overstated. The backpack kit brought the outside world to some of the country’s most farremoved places, raising aspirations, igniting ideas and stirring debate through the luxury of film. For most, it was a miracle.

When Grease’s finale song, We Go Together, rang out across Telegraph Hill, it seemed like the most natural thing to do to stand up and dance. Within moments, the entire audience was laughing and dancing, together. Without the constraints of auditorium seats, the cinema became a moonlit disco and Saturday Night Fever began. There is a beauty to it; how often do we cut loose and share a moment like that with our neighbours? Film can bring any community together to have fun and be inspired. And whether in the UK, where doors so often remain closed, or in the depths of rural Africa, where technology is minimal, Electric Pedals is pedalling the dynamic future of community cinema.

electricpedals.com freefilmfestivals.org gafi4apes.org 23

Julian Sayarer rode around the world, beating the record as he did so. Five years on, he looks back at the way the journey changed him, and the book, Life Cycles, in which he's gathered his thoughts from the road.

Words: Julian Sayarer

Illustrations: Paul Heredia

Me and the Bicycle

Throughout that journey, from a child to an adult, I suppose the bicycle became my touchstone, my talisman. Of all that will be sold away, please allow that the bicycle be the last thing to remain sacred.

I loved cycling through impulse, through instinct, and long before I was cursed to try articulating that feeling with words. Across the miles I’ve given it a great deal of thought, finally resolved that perhaps for me the bicycle represents some small saviour from mortality, the opportunity to make something greater of myself, to move with such speed and power that a portion of the mind is able to believe in magic, believe we humans are not after all so banal as I must otherwise confront. I love the bicycle like nothing else, the one institution I’m happy to live by, for in it you can feel euphoria.

Kash d’Anthe

It had started in Istanbul, the Cihangir crossroads, where I’d met a couple who were a year into cycling around the world. They’d told me of a Scot by the name of Kash d’Anthe, aiming to break a world record for a circumnavigation by bicycle.

Back in London I’d looked him up, and soon after, by chance, scarcely had to look for him at all… d’Anthe was well on his way to minor stardom, a subject for television, advertising and corporate endorsements. Come that time he’d broken the record, ridden 18,000 miles in little over six months, an average of 90 miles daily. The start of my curiosity was the feasibility of the target. Riding leisurely to Istanbul I’d averaged 70 miles a day despite lengthy breakfasts, no thought of haste and sitting in cafés scribbling stories for five hours each afternoon. And yet that alone would never have been enough to tempt me into the pettiness of that dumb record.

It was the manner in which d’Anthe went about his feat that roused my ire… snagged a pathological part of my personality I’m not the least bit proud of.

He was sponsored, up to the eyeballs he was sponsored… banks and investment funds all over his chest, his smiling face and a thumbs-up next to a business model that cared nothing for people or for bicycles, only the right numbers in the right columns of a balance sheet. I was well desensitised by then, didn’t expect much to be left sacred, but it was the final straw… to see the bicycle reduced to no more than a corporate marketing strategy. We had things in common… d’Anthe and me were not so very different, both in our mid-twenties, both politics graduates. I couldn’t fathom how someone of such similar years and education, of the same passion for travelling by bicycle, could come to hold such different priorities.

His pitch was a strong one, a stroke of genius. The financial sector he endorsed was without heart or love, working only for financial gain, and so the undertaking, ostensibly for spiritual gain and the joy of the task, was perfect. Their business wore suits and worked in skyscrapers while d’Anthe would see those who still lived in huts and dressed in loincloths, all traditional-looking to offset the garish and the modern. Finance wanted to be brave, to be beautiful… finance wanted to be adventure. They loved d’Anthe, were ready to make his whole life easier. They threw money at it… he sold… and with a smattering of charity thrown in, the banking world purchased a tiny piece of the human spirit.

I decided to go around the world, faster than him, and without bankers billowing my sails. The following excerpts are from the book I’ve since written about that ride.

25

Russia – Day 27 – 2,801 Miles

It was enormous. Russia. A place in which to realise just how you squandered all your superlatives of size back in the Ukraine. You see the trucks coming down the road from five kilometres away… thin pipes run above the wheels, trickle water to quell the heat that builds in the tyres. Road signs show cities 1,000 kilometres in the distance. The people are silent. They’d planted trees, twoskin deep, all along the roadside. It was so you couldn’t look out, out into the abyss, that endless vast that would creep into your mind and drive you insane. Occasionally at crossroads I would catch a glimpse of that sea I swam in, where I could drown in land long before there came a town in which I might slake my thirst and revitalise. As I rode, I saw squares, off-colour rectangles drawing closer. Houses, habitations… I thought I’d made it, that I was saved. And then I neared, and those squares and rectangles were only the spaces between the trees lining still more endless fields. Green, gold, brown and ploughed, black and ashen, the thing that never changed was it would always be only another field.

Kazakhstan – Day 35 – 3,722 Miles

In Kazakhstan I spent over 2,000 kilometres on a single road with hardly a turning, a gallon of water carried over my back wheel, pannier full of bread and jam, a head full of worst-case scenarios in which my bicycle broke down between settlements. The villages were 100 miles apart, then 150, and eventually 200. Imagine London were only a village, Manchester were another, and now imagine nothing in between upon that single road that joins them. You can see the towns in the distance, a single radio mast stands skinny against the horizon, comes slowly into view from 30 miles away. Kazakhstan is the ninth-biggest country in the world but with a population of just 16 million. I rode through some 3,000 miles of it… find it hard to believe even that many people are living there. The land delighted in its endless scrub, and among those wastes I found myself smiling, simply smiling, for never have I been so at peace. The steppe was just a mirror, could comfortably represent either stark death or perfect simplicity, and each time, against that landscape so eternal I realised all I saw was in fact only a measure of my own impatience or contentment. Out there I was humbled, so tenderly was I humbled, for I took with me all my earthly weight… my cynicism, fear, my ego and insecurity… and, when we arrived in those wastelands, they saw the world in which they wished to live, so that very soon, all had fled from me.

At dusk I watched settlements from afar, eating a small meal before disappearing back into the road. Trails went, kicked up behind the goats, the horses and bulls being driven back inside the mud walls of the village. A bell would ring from a short tower, and I watched figures sitting lazily on horseback as they rounded up the herd, lines of dust making their way slowly back through the gate from different points on the landscape. Those sunsets in the Caucasus were something else, a tiny, nightly supernova, like a hot ruby sinking to the bottom of a well… you could light a candle on them, smouldering in a pink that turned to blood. Peels of black cloud would sit upon the red, leeches sucking that firmament to the last before floating to the tops of the sky, greying, and then melting to join the night.

For a while I’d lay awake, growing certain the stars were breeding overhead. Every night there were more, new stars appearing among the million, white waves of cosmos trailing among them. Sometimes I would stare upwards and imagine the outside universe as nothing but light, the world itself wrapped in a black paper bag with tiny holes, pinpricks all through the walls and roof of our resting place. In those lands there was no need for a tent… rain was impossible and the mosquitoes could not survive, the silence too absolute for their wings to hum through. The stillness would play a lyre as I looked up at the sky, resolving to keep my eyes open until a shooting star had passed. In most places I have lived, such a game would have failed entirely, yet out on those plains it comes within five minutes. The tail of that burning rock would take a needle from those scrub thorns, and together they stitched closed my eyelids each night. The scrub sat over me, bathed my forehead as if a warm flannel, soothed me to sleep beneath those acrobatics.

China and car horns – Day 72 – 7,333 Miles

The car horns, ever the car horns wore me down, screaming all day long. They screamed that I move, screamed that they were coming… no thing too complicated, no situation too nuanced for explanation by car horn. Each time, for a whole month, it felt as though my eardrum was being spliced open with a blunt dagger. I grunted, grimaced, shouted, grew ever more furious, but it was futile – the car horn is invaluable to Chinese culture, it props up the nation itself. That horn expressed all standard scenarios of the road plus infinite more besides. I imagined the hidden rage that horn must have buried in the population, grew convinced

26

Chinese society retained its order by use of that horn and the frustrations it nullified. I’m 5’2” and identical to half a billion others, listen to this horn! My culture, history and ethnicity are repressed, listen to this horn! They think they’ve made an emancipated woman out of me but all they did was give me a truck to drive through a desert, listen to this horn! I’m a homosexual but don’t even know it because of this crushing, sexual conservatism, listen to this horn! Ten per cent economic growth? Maybe on the East Coast, listen to this horn! China, a great nation, then where are our basic freedoms? Listen to this horn! The sky is thick with smog, rivers run black and my child coughs blood… listen to this horn! Listen to this horn! No use gesticulating either for, if I waved a fist at them in rage, they simply took it for greeting or support and let off another volley my way. No concern could not be raised and answered by the blast of a horn. Like a psychiatrist’s couch, it saved them from themselves, it was their dissent, their protest, their therapy.

Thailand – Day 88 – 8,943 Miles

Thailand was kind to me, the coast drawing me out through canals and estuaries, beneath highways that lifted traffic above the water before sinking into Bangkok. Evenings broke with the smell of incense lit, and I watched people leaving their houses, slipping on a pair of sandals, the heels of which would clap against the ground as they strolled to shrines at the bottom of the garden. They placed gifts, put flames to incense, said prayers and bowed, unscrewing the cap from a bottle of water and setting it down for the dead to drink.

I remember the monk, sitting in orange robes upon the rear of a pickup truck driving by. He looked at me with a smile, put out a level palm in front of him, pushed it towards me and picked something from it with the thumb and fingers of his other hand. In his grip he lifted some invisible ball of sorcery, and with a flick of the wrist, he cast it into the air, blew… commanded his blessings upon me as his outline pulled into the distance.

27

America – Day 100 – 11,356 Miles

Those first two weeks in America I was on holiday, rode the most generous Pacific tailwind and still turned out the slowest fortnight of the whole six months… all of it lost in discussion of capital punishment and gun laws, watching the Pacific, singing aloud, full of Dylan as every state in the Union went down into my soul.

Oregon. It was Oregon that really did it… it was Oregon that sunk me. I rode through Oregon, through Oregon, through Oregon… I want to ride through Oregon every day for the rest of my life. All down that coast you climb up into the forests. Climb up. Climb up. The road tilts, hugs cliffs, hugs hillsides, runs under cover of the trees until you reach the top and begin to pick up speed… lots of it… more still, and then you’re sweeping back down, and up ahead the dark of the forest gives way to the light of the sun, and you sweep out the forest so that the sun it hits everything at once. And the trees, they are emeralds… and the Pacific, it’s sapphire, and it all glows white in the sun, and the Pacific… my god, but the Pacific it’s such a good name for an ocean. Rocking and fluttering and sparkling, with the turning pages of books and stories and gossamer yarns. The ocean moved against white sands with their dusty trunks of driftwood, washedup and tossed to the beach, like dinosaur remains and whale skeletons, a cemetery of rib cages and tusks from creatures of another world.

I would ride down those hillsides, my head would fall to one side, my nose and the corner of my mouth would lift in enquiry, eyes glazing in search of clarification. Really… are you sure? Excuse me, but there must be some sort of mistake… for this cannot be. I died about five times a day down that Oregon coast, don’t hesitate in saying it ruined the rest of my life. The air from the Pacific made me sad to think one day I’d have to breathe the air of the deserts, the air of a city, the air of any place other than that Oregon coast where I rode my bicycle. I saw infinity there… that was the problem. Right there in Oregon I glimpsed infinity. The history of the world came down to meet me, revealed all of the serene chaos that wound up beautiful. I saw it all in the palm of my hand, and with it my mind blew open, so that afterwards, once I’d pieced myself together again, so it was that I saw how small I was against it all, my blink of an eye that passes for a life. I know I probably don’t seem so very old to most of you, down here and still shy of thirty… and yet, once you’ve seen infinity… you come to realise how soon your time is up, how quickly it all goes by. Live life like you’re dying… that’s what I’m getting at, my advice in all this.

Day 163 – Castille – 17,103 Miles

I rattled big days: 150, 150, 150, 150, 150 miles… five in succession, knocking them off the bat, one after the next, with an average three hours sleep. I still like the ideal, that back-against-the-wall sort of stuff … but even with that… I’m not so sure I was enjoying life much by then. I hit La Mancha… La Mancha hit me back with a force far greater than I had spirit to resist, Don Quixote illustrated in town centres and bars for 100 miles, riding with horse and lance through the windmills of La Mancha in the name of chivalry and ideals. I chased after him with my bicycle and panniers, just as hopeless, the end of my quest for a world bettered by circumnavigation. The end was in sight, the money all but gone, my enthusiasm for records long a thing of the past.

And now, looking back, I have a peculiar relationship with the ride in so many ways. Despite the good intentions with which I set out to break the record, riding a bicycle around the world presents so many experiences that teach you how silly the idea of records is, and I was never that convinced to begin with.

The idea of racing against someone else’s time was at lots of moments a lot of fun... perhaps even more so with hindsight, it’s exciting to remember waking up after a few hours rest and knocking out another 150 miles. That said, my fondest memories, really, come from the very steady, manageable, hundred-mile days I rode for the first three months, through central Asia to Shanghai. If not then, then the days in the US, when I forgot about the record altogether and just stopped to talk politics, or took it so beautifully easy as I rode the Pacific Coast.

I think the record adds something to the book that I subsequently wrote; it lends a good narrative, and a context of time that I hope distinguishes it from a lot of literature from the saddles of touring cyclists. The sense of wanting to change the world, and the ideals I set out with, offered some strong touchstones that I always found myself returning to. The people you meet, and their own life stories, never stray too far from those same values, and now that’s how I see my book in some ways, the story of the world by bicycle. Next up is the story of the city by bicycle, drawn from three years as a courier in London. I’m still developing as a writer, just as we’re all always developing, either as people, or in the skills we turn our hands to. That’s what keeps the wheels of life turning.

Julian’s book, Life Cycles, from which the excerpts above are taken, is out now.

29

Standing inside the pipe, our eyes looked up to the funnel’s beginning, as if we were tiny ants trapped in a sink’s plughole.

THAT PIPE!

“Duuude! What massive alien pipe is this?” Tony screamed. “Damn, that’s totally off the hook!” I replied. Bit by bit we recognized my buddy Steve’s new profile photo on the laptop’s screen. He’s proudly posing in front of an enormous fullpipe made of concrete. We’d never seen something that huge before. Tony was so excited. He was partying inside. “We have to go there!” But Steve’s reaction was a bit of a downer: “That could be anywhere in the outback. You’ll never find it.” Big disappointment.

We’re from Germany, but were in Sydney, where Tony was looking for jobs, each and every day. We were in Australia to see as much as we could of the country, going from place to place with a disassembled BMX in the back of our car.

One day we visited the BMX shop Steve was working for in Sydney. Deep in conversation with the shop’s owner, Mike, about rad spots in and around Sydney, I felt thrilled like a rat on ecstasy pills. Mike had printed off maps and marked heaps of riding spots all along the east coast of Australia. Poring over these maps Tony suddenly yelled “THE fullpipe!” Fortunately Mike had been at the fullpipe with Steve some weeks ago, and could mark out the route and tell us everything about it. Bingo!

We had the red pencilled treasure map. It felt like christmas, birthday and a lottery win on the same day.

Words: Max Lehmann & Tony Haupt Photos: Tony Haupt / tonyhauptphoto.de

Words: Max Lehmann & Tony Haupt Photos: Tony Haupt / tonyhauptphoto.de

31

Alright. Tony didn’t find a job in Sydney and the weather forecast didn’t sound too good either. So we hit the road. Steve was definitely right when he said “It’s in the middle of nowhere”. We were driving for days at full speed, accompanied by rain, rain and some more rain.

We slept overnight in our cars, passing through tiny towns that looked like they’d been uprooted from some European country. ‘Skis and snowboards for hire’? Well, that was something mind-boggling. So we had a closer look at our huge map of New South Wales and suddenly it all made sense. We were heading slowly but surely towards the Snowy Mountains. As time and kilometres slid by, the roads were getting more and more narrow and winding. Bends for what felt like 200km, our ears aching from pressure. We crunched the last 25km along gravel tracks through milkvetch-fringed woods. After what seemed like an eternity we reached the end of a road, some 1600m above sea level. Suddenly a gorge and a vast dam appeared. Here we stood, with bated breath, waiting to see what we had dreamt of.

But at first glance there was no fullpipe to be seen, only a monstrous funnel-shaped thing. We had already clocked this via satellite photos on the internet as a suspiciously huge black hole, so we were sure we were in the right place.

Obviously a fullpipe like this isn’t part of your typical skatepark. This pipe wasn’t built to go for a family stroll. The only readily identifiable above-ground signs at the dam were ‘DANGER’ signs. That pipe’s black hole acted as an overflow for the huge artificial lake above the dam. We knew we’d found an opening, but to actually get in there we needed to march another twenty minutes to the ‘entrance’ – the overflow’s emergency outlet. The end, so to speak. We fought our way across loose boulders and after a few adventurous climbing manoeuvres we were inside. Inside the pipe!

After what seemed like an eternity we reached the end of a road, some 1600m above sea level. Suddenly a gorge and a vast dam appeared. Here we stood, with bated breath, waiting to see what we had dreamt of.

32

With every carve I got higher and faster, gaining confidence, swooping back down before pitching back up to those dark and dizzy heights.

The concrete was almost completely dry. We only needed to clear out the floor a little to get rid of the rubble before we were ready to carve a path around this alien channel. We inspected the 150-meter-long pipe. There we were, some 15 meters below the level of the dam’s stored water. Standing inside the pipe, we looked up to the funnel’s opening, high above. It felt as if we were tiny ants trapped in a sink’s plughole. With an uneasy feeling I rode my first cautious meters in that pipe. Uneasy, because if that emergency funnel was used we would have been washed out like ...ants from a sink’s plughole. The dam was already pretty much full. There were maybe one or two meters left that kept us alive - but it was raining, so we knew we hadn’t got much time. Since we love our lives, we shouldn’t risk too much.

But riding those strange subterranean curves was supernatural pleasure beyond description. With every passing minute the fun increased. With every carve I got higher and faster, gaining confidence, swooping back down before pitching back up to those dark and dizzy heights. I was deep underground and in the middle of nowhere. But I felt on top of the world and right at home.

34

I was deep underground and in the middle of nowhere. But I felt on top of the world and right at home.

Photos by Joff Summerfield / calloftheroad.co.uk

Words by Marc Simper-Allen

Photos by Joff Summerfield / calloftheroad.co.uk

Words by Marc Simper-Allen

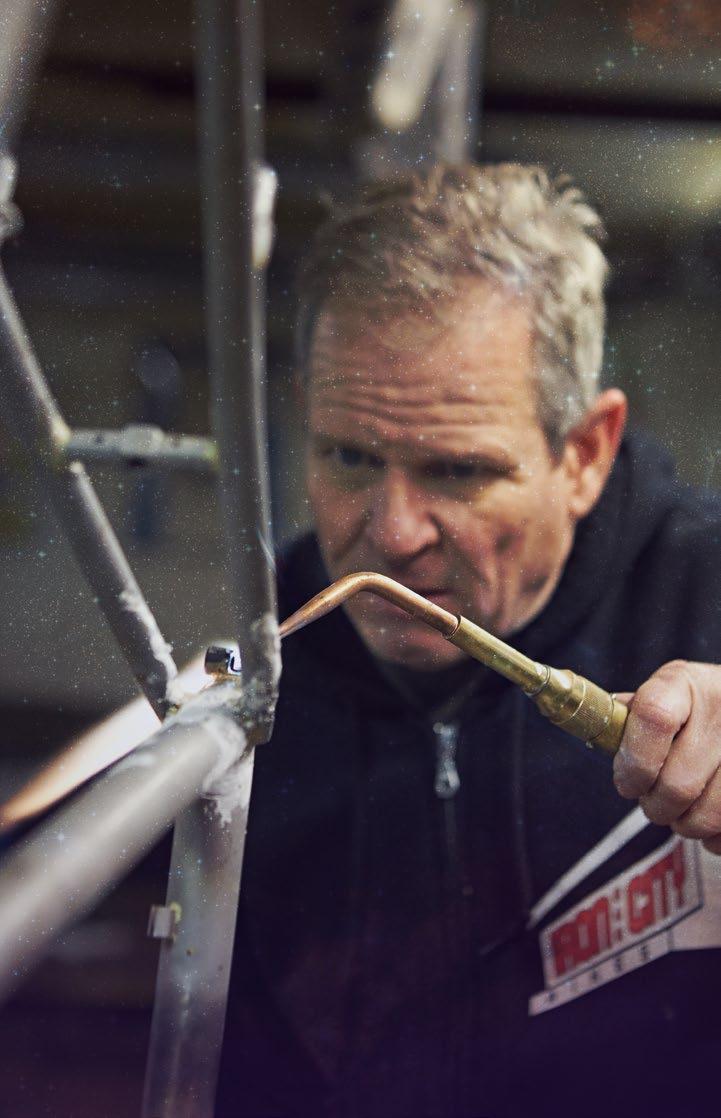

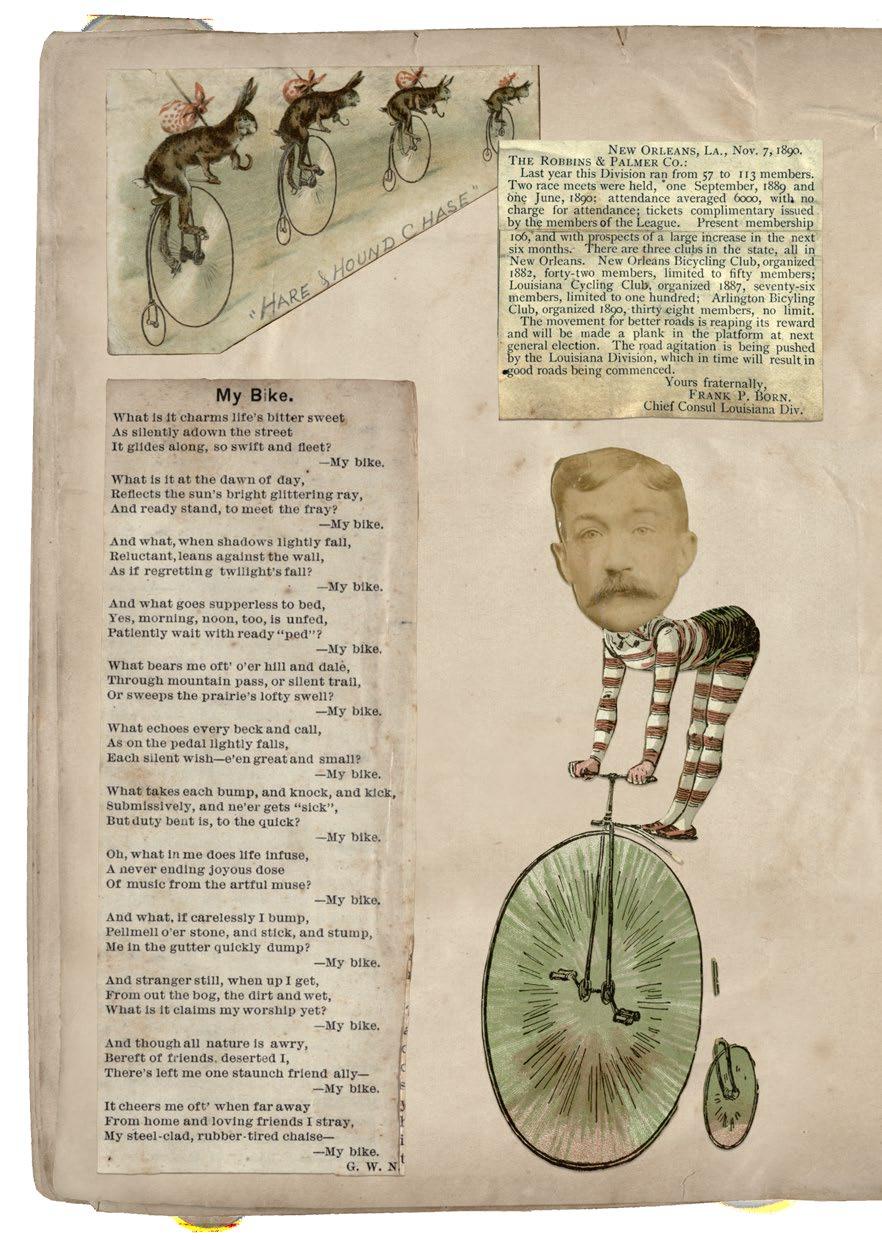

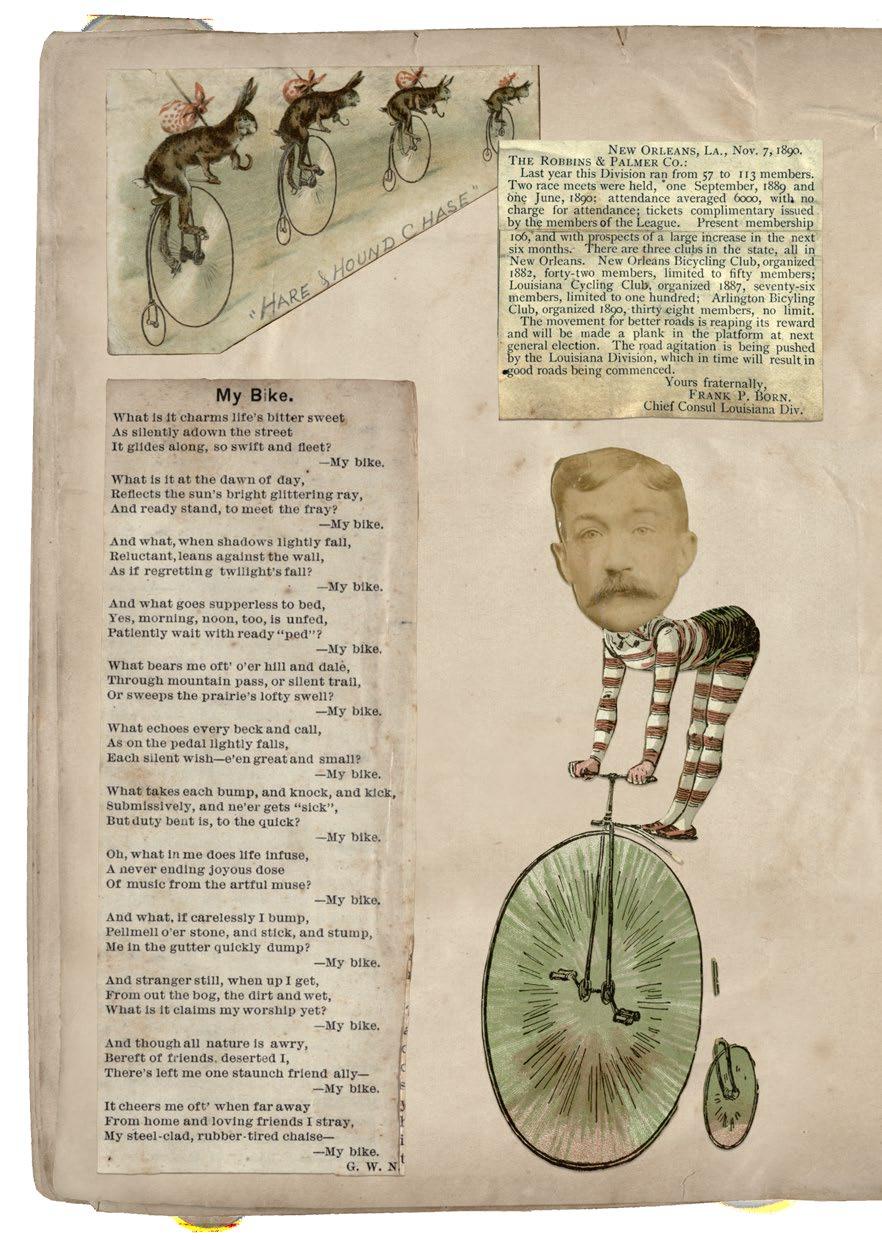

There’s an otherworldliness to Joff Summerfield.

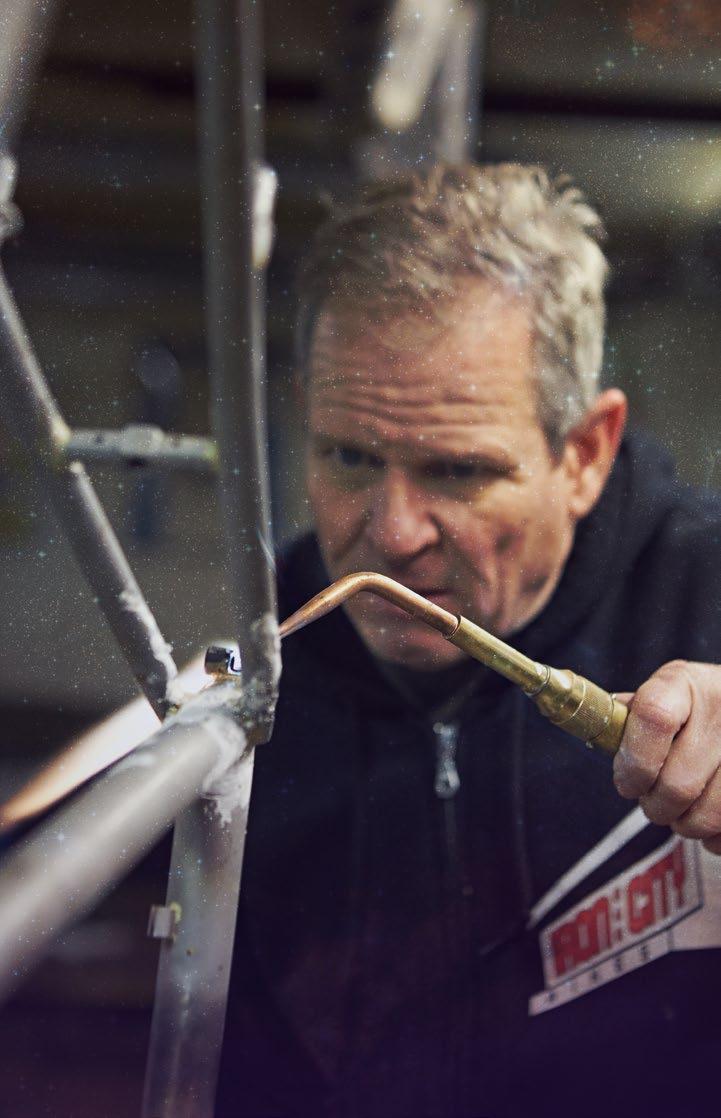

43, lean and spare, there’s something of the aesthete and visionary about him; it’s as if he’s discovered the meaning of life, and finds the world around him amusing, perplexing and all a little strange. He certainly has seen much of the world from a unique perspective: from the saddle of a penny farthing, and is only the second person ever to have done so. What makes the achievement even more remarkable is that he did it on a bike he designed and built himself.

Summerfield’s apparent detachment from the material world seems almost inevitable when you think about it. When a person’s whole existence, for months and then years on end, has revolved around a bike and the few possessions they can carry upon it, there emerges a peculiar and specific focus. Life is cut down to the essentials needed for day-to-day survival; the immediate problems of food, water and shelter. Those who have tried it know that it generates a feeling of complete liberty and self sufficiency, and that it’s addictive. That’s why Joff’s planning to ride around the world again.

39

Living in the loft above his Victorian workshop in London’s Trinity Buoy Wharf, he leads a spartan existence; making his unique bicycles in an old ships’ cable proving-house and saving his money for his next journey. One of a long line of workshops and studios, there are boxes of herbs on the window ledges and a dilapidated motorbike propped up outside. It’s tucked out of the way and the 19th-century setting seems entirely appropriate. Inside, it’s organised chaos; penny farthings in various stages of assembly hang from the rafters and tools are littered across the work surfaces. I’m offered black tea (all there is) made on the woodstove, and he starts to tell me about his journey and the bikes he builds for a living.

“I built them, broke them and then modified the design until I had something that didn’t break any more,” he says. Coming from a family with roots in classic racing and car manufacture, he was already well-equipped with the engineering skills needed to build his own penny, but had to visit a museum to see how one was actually put together. Now he sells them to customers around the world and his order book continues to grow.

His first attempt at circumnavigation got him as far as Folkestone, before acute knee-pain forced him to abandon the journey. Undeterred, he set out again, and got as far as Budapest, before the same problem stopped him. Some people might take that as a sign that man was not meant to circumnavigate the globe on a large, spoked wheel. Instead, he returned to the UK, sought specialist help, and with special knee-support bands in place, set out on his third attempt. Two and a half years later, and to high acclaim in the national media and cycling press, he returned; largely unscathed.

That first journey - in the cycle-tracks of Thomas Stevens, the Victorian cycling-pioneer - took him through Europe, the Middle East, the Indian Sub-Continent, the Himalayas, China and America. Now he’s planning to tick off the bits he missed, with South America and Africa high on the agenda. “The average day’s journey on a penny is about 40 miles,” he says. “That’s quite low compared to what a modern bike can cover, but there is something about the penny that is addictive.”

His adventures were many: he had crocodiles in his camp site; he was hit by a lorry; suffered two muggings; and was moved-on by gun-toting soldiers. “Every 18-year-old should be kicked out of the country for a year to learn about the world they live in. We’d have a much better society,” he opines. His outlook on life gives me pause for thought, and I find myself planning a round-theworld trip as we speak.

“I built them, broke them and then modified the design until I had something that didn’t break any more.”

40

Even during its heyday in the late 19th century, the penny farthing was known as a notorious killer. There’s a reason that the modern diamond-framed bike was marketed as the ‘safety bicycle’ when it was first introduced: the penny broke necks and impaled people on iron railings. ‘Wheelmen’, as they were known, were the daredevils of their day, akin to today’s freerunners and skateboarders.

Braking is especially inadvisable on a penny, as the rider sits directly over the bicycle’s balance point. As the front wheel slows, the lack of counter-weight from the rear means the rider simply rotates over this fulcrum and does a ‘header’ straight into the ground. As the legs are trapped under the handlebars, there’s fantastic scope for injury. “I’ve broken my wrist four times, my elbows five; my collarbone and my leg,” Summerfield says, “but they’re great bikes.” He did all this while racing his penny against other enthusiasts...

His preferred method of dealing with errant pedestrians and stray dogs is simply to ride them down; it apparently does less damage. Bumps and potholes are equally dangerous, necessitating much dismounting and pushing. Imagine taking such a machine through the high mountain passes of Tibet and the jungles of Cambodia. Thomas Stevens’ account of his circumnavigation (1884-87) is littered with headers, collisions and stretches where he had to get off and push. It’s a wonder either of them made it down the garden path, let alone around the world.

So why on earth attempt long distance touring on such an impractical machine?

For all its danger, the penny farthing has a certain purity of essence that many people find irresistible. It’s the original fixie. There are no gears. There isn’t even a chain. There is nothing to come between the rider and their direct connection to the road. The rider is literally, ‘riding a wheel’. It’s a little like using a quill and home-made iron-gall ink to write a letter. It is simple, elegant, and instead of relying on over-complicated technology to work, it relies on skill. And more than a little bloody-mindedness.

Equipping yourself with a top-of-the-range expedition bike can cost thousands of pounds. They can have hub gears, suspension, computers, dynamos to power your laptop and a whole host of other ‘essentials’. Summerfield went to the opposite extreme and built the simplest of bicycles; and in so doing, proved that guts, determination and a sense of humour are far more important to a round-the-world tour than the latest gizmo.

To cycle around the world takes a certain spirit of adventure and a large degree of fortitude. To do it on a self-built penny farthing takes a certain type of brilliant madness. Overused perhaps, but the phrase, ‘mad dogs and Englishmen’ comes to mind after talking to Joff Summerfield. Well, long may mad dogs and Englishmen venture forth in the noonday sun. The world would be far less fun without them.

43

“Every 18-year-old should be kicked out of the country for a year to learn about the world they live in. We’d have a much better society.”

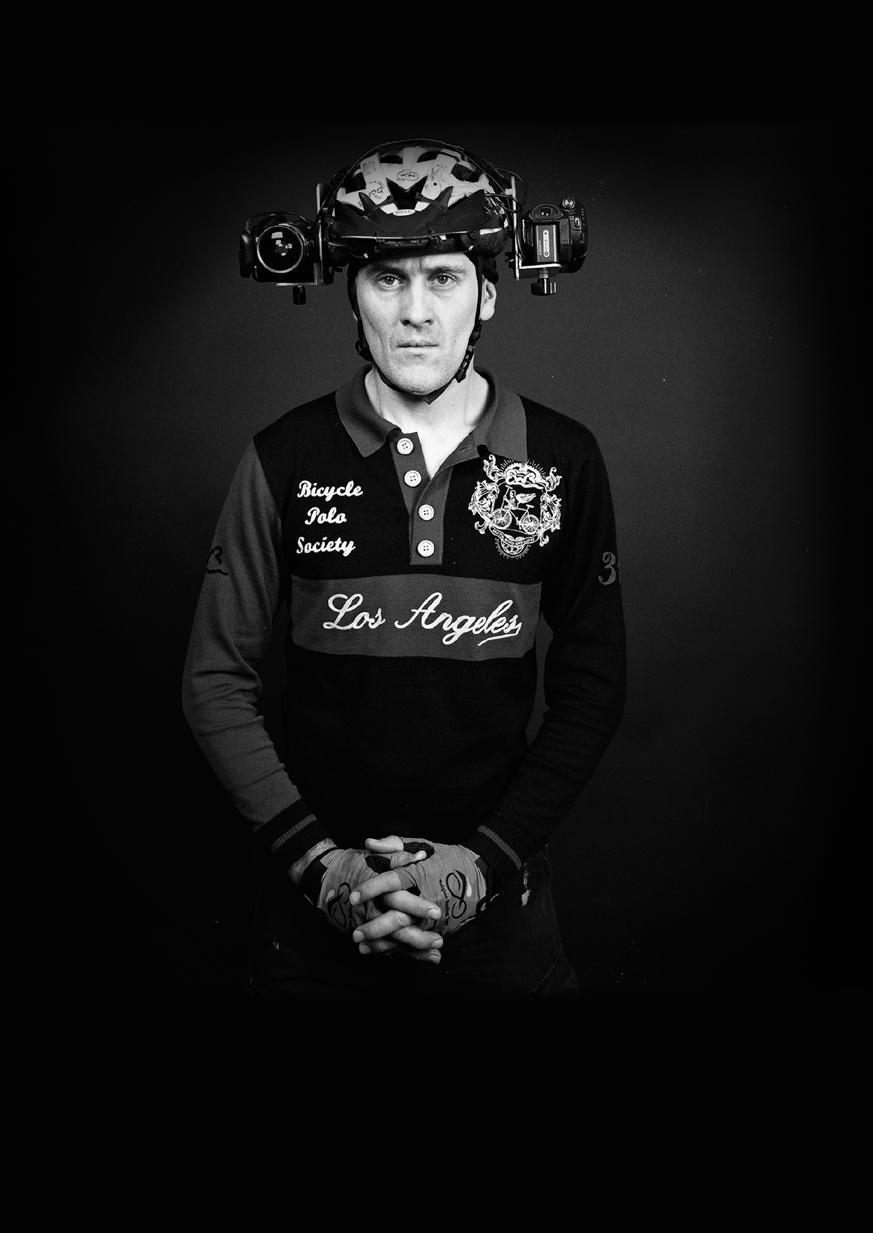

Words: Mike White.

Pictures / film stills: Lucas Brunelle & Benny Zenga. All rights reserved.

A SPACE THE EYE CANNOT SEE

Lucas Brunelle grew up in sleepy Martha’s Vineyard, USA, enjoying “the kind of childhood that produces psychopaths and career criminals,” riding BMX and getting into trouble. He slid in and out of jail and reform school. Returning home after a spell of detention at 16, he founded his own landscaping business and used the proceeds to buy his first road bike from Cycle Works bike shop. “I hung out at the bike shop on rainy days and ran into a couple of racers who invited me to come with them to the Plymouth Rock Criterium. Seeing this race changed everything for me – the speeds, corners, tactics, aggression and rain all added up to my destiny.”

He started to train, and race, and win. Had sponsorship for a while, but his troublesome side brought him down again – his coach Frank Jennings was busted for coke dealing and Lucas ended up with a two-year suspended sentence for “18 felonies plus numerous other serious offences” including burglary and dangerous driving.

He did his time, pulled himself together, went to college, got a job on Wall Street and then set up an IT business, all the while racing and winning. But Lucas no longer got the same buzz out of riding. “It was like the passion was gone. I did well by taking risks and being aggressive. I often rode tight courses like I was on a BMX bike and dropped riders that were much faster than I was – but for what? Amateur racing is filled with catty dickbag riders who think they’re better than you even if you win the fucking race. I was stuck racing Cat 2, trying to decide what to do. I kept couriering and fixing people’s computers. I went on Critical Mass rides for comic relief and it was in 2001 that I met my friend John McLean, who sported a shoulder camera. Bikes had helped me get out of a self destructive cycle, but it wasn’t until I saw his footage that I finally understood my calling in life.”

That calling has proved to be the development of a unique and frankly terrifying brand of cycle cinematography. He films alleycat races from right in the quickest thick of the action, keeping level with the riders as they hurtle through the busiest cities in the world.

For those that don’t know, alleycat races involve riding at breakneck speed through the traffic, battling to be first to complete a series of checkpoints on a wild-goose chase across the city. There are no fixed routes and few rules. Usually the only rule strictly adhered to is that bikes must have no gears and no brakes. The only way these riders can slow or stop themselves is by locking the fixedgear rear wheel into a skid.

The checkpoint locations are usually issued to riders on a manifest at the start of the race. To add an element of chaos to the proceedings, manifests are often thrown into the air. The riders’ bikes may be strewn at random around them; the first thing to do after you’ve fought for a manifest is to find your bike. Then you’re off, using your wits and your legs to get round the checkpoints fastest. With no fixed route, knowledge of the streets is a big advantage - but following the rider in front offers no guarantee of success.

Imagine you’re in New York city – though it could be London or Berlin or Tokyo or anywhere - you’re riding at lung-burst pace, absolutely flat out. Your brakeless bike sways beneath you in time to your furious cadence. Someone leans down and grabs the wheel arch of a passing cab, enjoying a free ride for a few blocks. Your competitors whoop and holler as they swerve and dart between the tight-packed traffic.

45

“THOSE SPACES, THOSE OPENINGS, THOSE BLIND SPOTS...

THAT'S THE SPACE WE EXIST IN. A SPACE THE EYE CANNOT SEE.”

Up ahead, a cross-roads. You barely have time to register the red lights before you’re past them, taxicabs and trucks bearing down on you from all sides. You swerve left behind a bus, then power right, inches from the bull-bars of a pick-up. Horns are blaring wildly. A rider in front tumbles over a station wagon, his bike clattering to the tarmac. But you must push on, lunging and feinting through the snarling traffic, whipping round sleep-walking pedestrians, cutting corners, bouncing down steps, running your fingertips along the side of a bus as it thunders past in the opposite direction.

Lucas Brunelle rides with the very fastest riders in these races, taking even more risks than they do: he has two cameras strapped to his helmet, one pointing forwards, the other back, and even at the busiest intersections he doesn’t look left or right. He relies on steely nerves and a highly developed peripheral vision, keeping his cameras focused on the riders ahead and behind.

These races are controversial to say the least. They’re generally unauthorised and often illegal. The racers’ breathless bravado can scare the general public, catching drivers and pedestrians unawares. In a recent UK TV show sensationalizing the ‘war’ between cyclists and other road users, snippets of Brunelle’s footage were used (out of context, in a highly manipulative way) to highlight just how dangerous and out of control modern cyclists really are. Alleycat racers are often blamed for giving cycling a bad name, for committing all the clichéd crimes – riding on the pavement (sidewalk), jumping red lights, playing fast and loose with the rules of the road.

Those who defend such rides highlight the astonishing skill the riders possess. They make urban traffic look every bit as slow and lumbering and bovine as it is. However crazily they ride, they’ll never be as hazardous to health as the city-choking, obesity-encouraging, motorised traffic they so nimbly negotiate.

Whatever the rights and wrongs of the races themselves, the footage Lucas has collected makes for compelling viewing – as seen in his films Line of Sight and Road Sage, directed and edited by Benny Zenga – a long-term friend of Boneshaker.

Brunelle’s commitment is absolute. For him, riding like this adds a level of hyper-existence to life. It acts as a wakeup call to those who are not living their lives as fully as they could be, to “give them a poke”, “to awaken them … to make them aware of themselves, of their potentiality.”

He follows the races around the world – often the best alleycats form part of the annual Cycle Messenger World Championships, an international competition hosted by a different city each year.

“It’s always the same riders up front, the same riders winning these events,” he says, “because they have that skill... being able to go in a space that the eye cannot see. It’s a place in between cars, in between trucks and buses, taking a certain line through a curb, a corridor, that people just don’t realize is there… we use those spaces, those openings, those opportunities, those blind spots, and that’s the space that we exist in, where we race. There are certain things in life that require total complete focus and this is one of them.”

Lucas Brunelle nowadays is a man of pure focus. After 30 years of racing and 13 of filming, he’s open about his troubled past, using it as a tool to show people that they can “rise above anything”. He doesn’t drink or use drugs. But he does not deal in half-measures; he has a reputation as someone whose commitment to the extreme reaches almost to the point of cliché.

He thrives on calculated risk, speed and chaos, yet he finds a kind of spiritual purity in all this swiftsidestepped danger. The voice-over in his latest project, Road Sage, throws a meditative, transcendent light on the footage, bringing together voices as disparate as Henry Miller, Ben Okri, Allan Kaprow and David Foster Wallace:

“There are totally different ways to think about these kinds of situations – in this traffic, all of these vehicles stuck and idling in my way, you get to decide how you’re going to try to see it. If you really learn how to think, how to pay attention, then you will know you have other options. It will actually be within your power to experience a crowded, hot, slow consumer hell-type situation as not only meaningful but sacred - on fire with the same force that lit the stars. The liberated spirit… not being enslaved by the stupidities or by the rules of the machine of today. The big thing is to keep the flame, keep your own flame going. Take a chance – go nearer to the edge.”

lucasbrunelle.com

49

Papergirl The

Words: Alex Throssell

Illustrations: Gill Chantler | gillchantler.com

As unassuming as a leisurely group ride around norwich may sound, it was probably the greatest ride of my life

In the space of two months, I met and then lost possibly the most influential person in my recent years.

It was at a battle of the bands gig in late March that I first met Kiama Petit: a friend of a friend and an uncontrollable bundle of positive energy. In the quiet between acts, she raved about local bike-builder Tom Donhou and told me about the Norwich Papergirl ride, her art-meets-bikes end of university project.

By the beginning of May, four weeks after the Papergirl ride, Kiama, still only 21 years old, unexpectedly passed away.

A year and a half later, all of the good things that have happened to me since can, in one way or another, be traced back to that Papergirl bike ride. In fact, it was on that single day that I (almost) met the love of my life, found one of my closest friends and got to know the people at the bike shop I’d go on to work with for the next year or so.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing, but all too often I seem to focus on the negatives. Especially after a long day’s riding, I rarely remember the sunsets, the descents and the the conquered heights, but can far too vividly recall the rain, the wind and the punctures. The more fortunate amongst you might experience the catharsis of having it the other way around, but for me, it’s the grind, the pain, and the frustration that tend to repeat for a long while after. For possibly the only time I can remember before or since, the Papergirl ride was different.

As unassuming as a leisurely group ride around Norwich may sound (and, truth be told, as unassuming as the actual cycling was), looking back it was probably the greatest ride of my life. And although that sounds far fetched, I think that was the point all along. Kiama’s university studies focused on the ‘participatory, analogue, non-commercial and impulsive.’ Her mantra for the Papergirl ride was that art, and the gift that it gives, should be a part of everyone’s daily life, even if it’s just to brighten it for a moment. Some, like me, would experience a fiercer brightness than others.

To pimp our rides a little before the event, Kiama arranged a free-for-all customisation session at a newly opened community bike project. Aided by the project’s founder, Jason, we went about transforming our bikes. Several hours later I rode away with a handcut kaleidoscopic wheel cover, whilst others had attached flags, tassels and flowers. When we left, now considerably more eye-catching than when we arrived, I had no idea I’d return to that workshop in September, shake hands with Jason, and start a new job as a bicycle mechanic.

Although the group was modest - only 21 cyclists in total - it covered a brilliant spectrum. From young girls to old men, to people like me who just wanted to look cool, each carried a custom messenger bag full of carefully wrapped artwork and spread happiness by gifting a random piece of art to whichever passersby we chose. Part of the bunch, but often riding with

me up front, was a similar-minded bike nut who whooped “Free art!” in a range of accents, introduced me to fixed gear riding, suggested we turn an old house into a bike café and became one of my best friends in the process. And just as the Papergirl riders were a rag-tag, happy-go-lucky bunch, so too were the recipients of the random art-gifts. There were curious children, smiling pensioners, surprised exclamations of “and it’s free?”, and one particularly notable bohemian cyclist-type who swerved across two lanes of traffic with reckless abandon at the promise of free art, joyously colliding with a kerb seconds after claiming his prize. Although I didn’t know it then, one of the art gift receivers just so happened to be the girl I would fall in love with – a fact I was to discover on our first date six months later.

Even though it went against the whole spirit of the event, by the end of the ride I’m pretty sure we’d all had an urge to purloin a piece of art ourselves. I know this because over the course of the day several people asked Kiama whether they could take one as a memento. But with the integrity of her project in mind, she politely informed us that we were to give everything away and that we’d hopefully come away with something ourselves as a result. I’d guess that a few probably flouted her advice regardless, but for those like me that dutifully obeyed, Kiama’s words resonated more deeply than she may have intended. And indeed, the gifts that I took from the day were far richer than any piece of art could ever have been.

Cut down by a completely unexpected brain aneurysm, Kiama’s last great act was the spread of happiness to whoever would receive it, all from her trusty sit-upand-beg. And oh, what a wonderful world it would be if we all cycled the same way. It was just one day, and only a few hours on the bike, but I found the love of my life, one of my closest friends, and made memories that will stay with me forever.

In memory of Kiama Petit

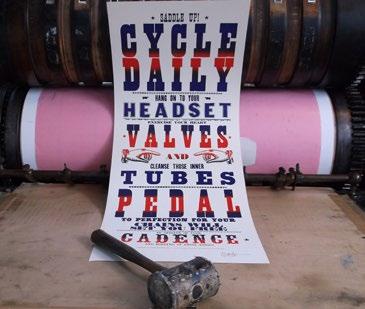

52