11 minute read

Driven By Faith & Audacity

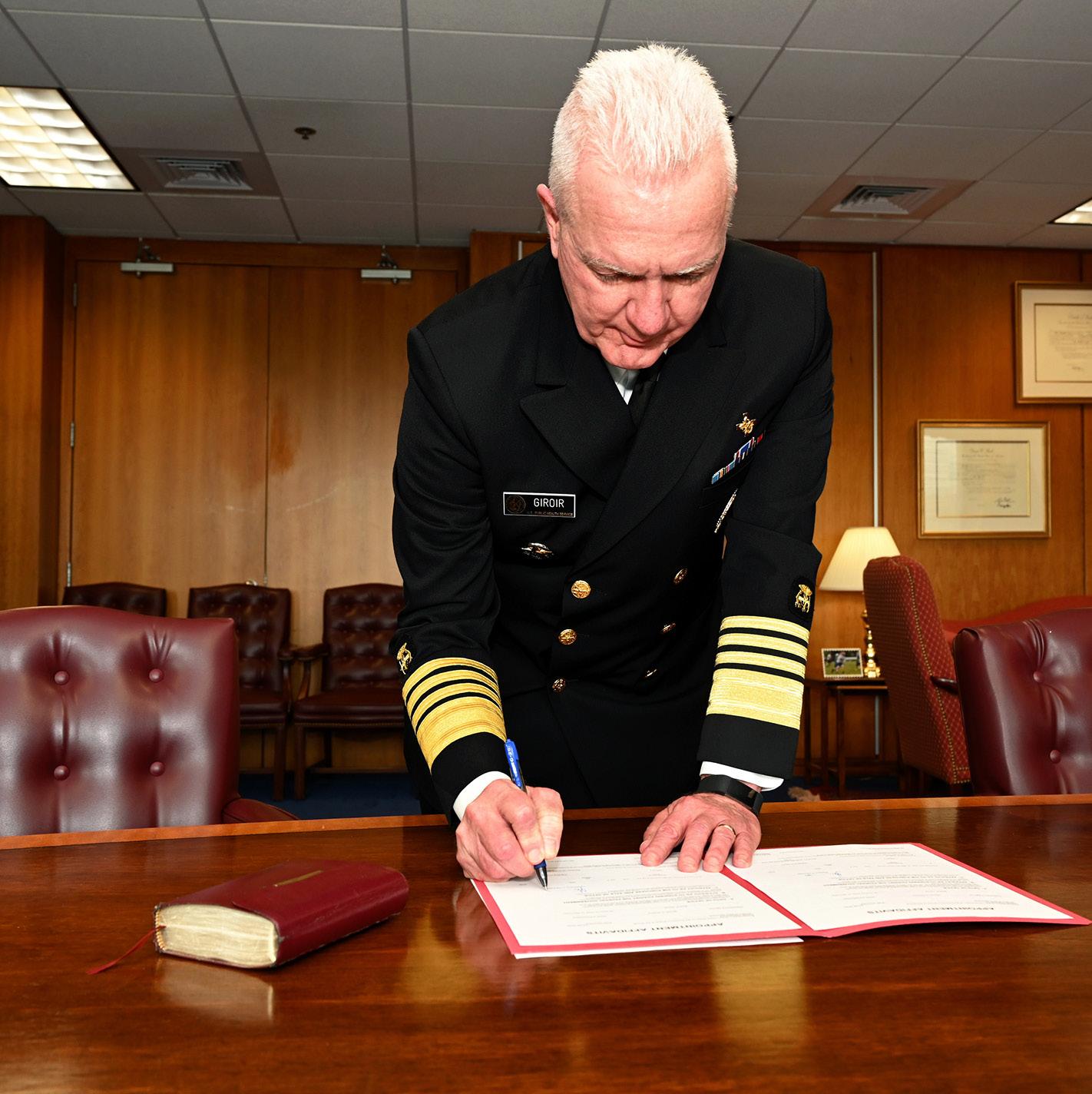

ADMIRAL BRETT GIROIR ’78

BY CHRISTIAN BAUTISTA ’06

Some 172 years ago, an enterprising cohort of Jesuits in France established the Jesuit College of Mongré in Villefranche-sur-Saône. Amidst the 1848 Révolution de Février—the February Revolution—and the birth of the French Second Republic, the founders of the school could hardly have known that it would persist until the present day. Their boldness was rewarded when a half century later a young Pierre Teilhard de Chardin entered their tutelage from the nearby tiny village of Orcines. Destined to take up the mantle of many Jesuit scientists before him, Chardin would profoundly impact the Jesuit, Catholic, and secular worlds. A paleontologist, geologist, and philosopher, Chardin would later write:

What paralyzes life is lack of faith and lack of audacity. The difficulty lies not in solving problems but expressing them….The day will come when, after harnessing the ether, the winds, the tides, gravitation, we shall harness for God the energies of love. And, on that day, for the second time in the history of the world, man will have discovered fire.

Blue Jay graduates will note the conspicuous founding year of the Jesuit school in Mongré, and indeed it was exactly one year earlier in 1847 that intrepid Jesuits in New Orleans, Louisiana established the College of the Immaculate Conception, known today as Jesuit High School, New Orleans. Providentially, both these French and American Jesuit schools persevere and thrive into the 21st century, and, in step with monumental Mongré alumni like Chardin, innumerable ranks of Jesuit New Orleans graduates have pursued science, faith, and service with equal fervor. There are, however, some who stand out even amongst this laudable company, and scant few Blue Jay alumni embody the signature Jesuit fusion of intellectual depth, spiritual grounding, and servant leadership as completely and authentically as Admiral Brett Giroir ’78.

During the first half of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic relegated billions of men, women, and children to their homes. Marked by economic uncertainty and social distancing, these times found a nation’s eyes affixed to televisions, phones, and tablets as daily Coronavirus Task Force briefings streamed from the White House Press Briefing Room. In this time of doubt and fear, a Jesuit Blue Jay from the Class of 1978 was called upon to bring stability and assurance to a shaken public, and there is no doubt Brett Giroir was the right man for the task. With a diploma from Jesuit High School, a B.A. from Harvard College, a career in pediatrics and immunology, multiple higher education leadership appointments, an extensive scientific research portfolio covering public health and vaccination, and military credits ranging from a director-level seat at DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) to a fourstar admiralship in the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, Giroir was an unassailable choice. Blue Jays should find inspiration not only in his service to the country during the pandemic-stricken days of early 2020, but even more so in a life animated by an abundance of faith and audacity—rather than, as Chardin warned, paralyzed by a lack thereof—that has taken Giroir from the west bank of the Mississippi to the north bank of the Potomac.

Giroir grew up in unassuming 1970’s Marrero, Louisiana, and, by his own description, “We didn’t have anything on the West Bank. I mean, there was nothing there.” In fact, faced with chronic hearing issues as a young child, he was forced to cross the river to find an ENT. “The ear specialist was right on the corner of Canal and Carrollton. I would pass by Jesuit, and I saw all the guys out there in khakis and their marine uniforms, and it fascinated me. It was a place that made me think, ‘I want to be part of that.’”

Looking back at this unlikely encounter and at other uncanny moments in his life, Giroir comments,

Reflecting on the transformation he underwent over his years as a Jesuit student, he asserts, “Jesuit formed me as a person.” Intellectually, this formation began on day one. Giroir notes his engaging Latin classes, a mind-bending eighth-grade physics class (a lapsed tradition), and an especially memorable government class with Fr. Wayne Roca, S.J.:

I still remember it opening my mind— reading Plato and the Allegory of the Cave and understanding what reality is versus perception. It was very demanding, and it was a very tough class. But it made me highly interested in understanding moral philosophy—secular moral philosophy in addition to religious moral philosophy. I pursued that at Harvard and beyond, too.

Giroir recalls that “No matter who you are or how smart you are, you’re going to be challenged by the Jesuits—that’s the tradition,” and he remembers being held to high standards regarding “intellectual rigor, asking questions, and forcing yourself to not be sloppy in your thought processes. That’s what it was about for me academically—on the philosophical side and the science side.”

On the “science side,” as it were, he points to a watershed moment in his experience at Jesuit that would substantially affect his path in life. “I remember that moment,” he affirms, “because it really drove my whole medical school and research career.”

In AP Biology I asked a question that I’ve still been asking for the rest of my life. That’s when I started getting interested in immunology. I just asked the question: why do people get sick when they’re infected? And it seems like a stupid question, right? But really it has nothing to do with the virus or bacteria; it’s your response to that. So what is it—what is it that makes you sick? No one knew at the time. I would get an answer to this question much later, but the question first came to me at Jesuit.

While his time in Jesuit’s classrooms formed him into an inquisitive, careful thinker, Giroir’s time outside of the classroom honed his rhetorical skills and leadership abilities. Jesuit’s debate team hall of fame memorializes Giroir’s “legendary” senior debate season in which he and classmate Moises Arriaga ’78 led the team to city, district, state, and national championships. It was, in fact, Giroir’s prowess as an orator and his securing of the title of 1978 National Debate Champion that caught the attention of the Harvard debate coach, who ultimately invited him to apply to the school.

When he takes the podium for interviews or press briefings, four stars representing his commissioned admiralship glint from Giroir’s lapels, but he claims that his development as a leader began at Jesuit. “Lt. Colonel Quinn was the Marine Corps officerretired who ran the program, but the staff was stacked with incredible people who had fought our nation’s wars and who were really dedicated to bringing up young men. In the JROTC, you were taught what it took to be a leader. I remember that like it was yesterday.” Emphasizing the discipline and structure that ROTC brought to his time at Jesuit, he muses, “I don’t know what the team drills with now, but we had M14’s. Everybody has scars from the triple sights on the end of them, but it was a great experience—I was commander of the drill team my last year. The whole ROTC experience was really important to me.”

Summing up the competency and preparedness that emerged from his Jesuit education, Giroir remarks, “I worked as hard or harder at Jesuit than I did at Harvard. It was not a big deal for me. The competition was steep, and there were incredible people. But so many people didn’t succeed because they didn’t have the discipline and the understanding of how to learn. Those things you learn at Jesuit because it’s the whole package. The camaraderie, the brotherhood, the service orientation— it really is the foundation of your life.”

Even before entering medical school, Giroir would go on to publish three papers in major medical journals as an undergraduate after clinching a research position by literally sneaking into the back door and up the service elevator of the Enders Building at Harvard Medical School. He laughs about the experience now: “If the front door isn’t open, sometimes you have to bang your way into the service elevator to get your chance. For me it led to a love for science, and I was able to go to clinic and take care of children with autoimmune diseases and really learn what it was about.”

This unstoppable passion for science combined with a dogged pursuit of the nagging question from high school biology—what actually makes us sick?—would lead him to medical school at UT Southwestern, where he studied with Dr. Bruce Beutler. During Giroir’s tenure as a medical student, Beutler went on to win the Nobel prize for exploring the underlying chemistry of disease and infection; in yet another toocoincidental occurrence, this research experience that had seeds in a Jesuit biology class would eventually underscore Giroir’s service to the country during the COVID-19 pandemic. Giroir chose to train as a pediatrician at Children’s Medical Center Dallas and Parkland Memorial Hospital, where he focused his talent and energy on working with underserved populations who, as he reports, “did not tend to have lots of options.”

As the son of a police officer and an oil field worker, Giroir insists that his commitment to bring to life his scientific and medical interests through a career of servant leadership comes from his own family but also from the lessons he learned as a Blue Jay. Fighting back tears as he describes his pediatric career working with children diagnosed with sickle cell anemia, he says, “When you’re in a position of power and authority, it’s your duty to use that for people who generally don’t get paid attention to. And for me people with sickle cell are on that list, but a lot of other people are on that list.” Jesuit taught him to be compassionate, he says, and to always ask, “How am I going to lead my life so that I give back the gifts I’ve been given?” When faced with making career decisions, Giroir explains his personal path as grounded in the Jesuit notion of becoming a Man for Others:

There’s sort of a baseline of “I want to do this because I want to help other people.” I know it’s trite, but you go into medicine because you want to help other people. You go into pediatrics because you want to help kids. You do science because you want to help even more people. Then you start going into policy and public health because you keep seeing kids in the ICU every night with head injuries, and instead of wanting to keep putting bolts in their brain you ask yourself, “Why am I doing this? I need to get out the public and teach people to use car seats.” So, I think it’s all about being able to influence things at a big level that impacts a lot of people.

By mid 2018, the man who began life as a tenacious boy from Marrero had assumed the title of Admiral Brett P. Giroir, M.D., Assistant Secretary of Health. In this role and his role on the Coronavirus Task Force, Giroir has been faced with countless moral and ethical challenges. Like the Jesuittrained Teilhard de Chardin, though, he sees faith and science mutually illuminating rather than mutually opposed.

The director of the National Institute of Health is a strong Christian and a top scientist in the country. Bob Redfield, who runs the CDC, is a profoundly devout Catholic—he has a rosary with him everywhere he goes. The secretary of Health and Human Service is an orthodox Christian. There is no controversy whatsoever with being a religious individual and being proscience. I don’t like the accusation that Pro-Life people are anti-science. Legitimate science is always bounded by ethical principles. We don’t experiment on people without their consent because that is unethical. We don’t experiment on prisoners or disabled people because there is an ethical bound to that methodology. We don’t clone humans because it crosses agreedupon ethical boundaries. We don’t give a placebo when we know there is an effective treatment that could help a patient.

In the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and during his busiest, most unpredictable weeks on the Coronavirus Task Force, Giroir made time to offer words of encouragement to the Class of Jesuit 2020 and to the Jesuit community at large.

I want everybody to know how much they need to appreciate the time that they have there. It’s a very special, fundamental, and foundational time. You will never have it again, and you will appreciate it in retrospect. And I hope the faculty and staff and all the Jesuits really always know what an indelible mark they make on lots of people for decades after their time at Jesuit.

Giroir’s steady-handed leadership embodies the most abiding virtues of a Jesuit education—virtues championed not only by the likes of Chardin but also by Jesuit alumni the world over. Animated by faith, tempered by humility, and yet audaciously driven to once again “discover fire,” Jesuit graduates who aspire to improve the lives of others should take inspiration from this gallant fighting son from Marrero.