WWW.NBN.ORG.IL • 1-866-4-ALIYAH • ALIYAH@NBN.ORG.IL FACILITATE • CELEBRATE • ADVOCATE • EDUCATE WORKING IN PARTNERSHIP TO BUILD A STRONGER ISRAEL THROUGH ALIYAH YOUR ALIYAH PHOTO HERE

Summer 2023/5783

OU KOSHER CENTENNIAL SPOTLIGHT

Rabbi Berel Wein

By Steve Lipman

HEALTH AND WELLNESS

Taking Charge of Your Health

By Rachel Schwartzberg

By Rachel Schwartzberg

COVER STORY THROUGH THEIR EYES: ISRAEL AT 75

The Medinah: Through a Torah Lens Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik; Rabbi Dr. Yitzchak Isaac Halevi Herzog; Rabbi Shlomo Yosef Zevin; Rabbi Tzvi Pesach Frank; Rabbi Yehuda Amital; Rabbi Yaakov Friedman; Rabbi Dr. Aharon Lichtenstein

The Birth of the Jewish State: Rabbinic Views and Perspectives

Compiled and translated by Rabbi Eliyahu Krakowski

The Return to Zion

An Excerpt

By Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik

Voices of Faith: Memories of 1948

By Rabbanit Miriam Hauer, Rabbanit Puah Shteiner and Rabbi Berel Wein

Interviews by Toby Klein Greenwald

A Bridge of Paper

By Charlotte Friedland

DEPARTMENTS

LETTERS

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

Zionism

By Mitchel R. Aeder

FROM THE DESK OF RABBI MOSHE HAUER

The Gift of Israel

ON MY MIND

The Allure and Illusion of Ownership

By Moishe Bane

JUST BETWEEN US

What’s So Great about Being a Jewish Educator?

By Rabbi Rick Schindelheim

KOSHERKOPY

Unscrambling the Kashrut of Eggs

THE CHEF’S TABLE Cool It

By Naomi Ross

LEGAL-EASE

“What’s the Truth about the Kotel Being Judaism’s Holiest Site?”

INSIDE THE OU

By Sara Goldberg and Batsheva Moskowitz

INSIDE PHILANTHROPY

New Grant Bolsters OU Program

Providing Financial Counseling

BOOKS

Gratitude with Grace: An Inspirational and Practical Approach to Living Life as a Gift

By Sarah S. Berkovits

Reviewed by Alexandra Fleksher

Across the Expanse of Jewish Thought: From the Holocaust to Halakhah and Beyond

By Hillel Goldberg

Reviewed by Ben Rothke

LASTING IMPRESSIONS

Our Tenth Aliyaversary By David

Olivestone

magazine contains divrei Torah and should therefore be disposed of respectfully by either double-wrapping prior to disposal or placing in a recycling bin. 83

Cover: Andréia Brunstein-Schwartz

By Rabbi Dr. Ari Z. Zivotofsky

FROM THE DESK OF RABBI DR. JOSH JOSEPH

This Jewish Action is published by the Orthodox Union • 40 Rector Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10006, 212.563.4000. Printed Quarterly—Winter, Spring, Summer, Fall, plus Special Passover issue. ISSN No. 0447-7049. Subscription: $16.00 per year; Canada, $20.00; Overseas, $60.00. Periodical's postage paid at New York, NY, and additional offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Jewish Action, 40 Rector Street, New York, NY 10006.

1 Summer 5783 /2023 JEWISH ACTION

INSIDE

| Vol.

FEATURES

83, No. 4

63 20 18 2 0 32 52 58 63 74 2 5 12 77 80 83 86 90 95 96 102 108 110 112

We Belong Jewish Action seeks to provide a forum for a diversity of legitimate opinions within the spectrum of Orthodox Judaism. Therefore, opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the policy or opinion of the Orthodox Union.

Touro’s Lander College for Men provides a unique opportunity for those who are devoted to Torah study and determined to succeed professionally. From business to biology, accounting to computer science, you’ll find a program that’s right for you. Tell us what your aspirations are, and Touro will take you there. LEARN MORE GO FURTHER Contact Rabbi Aryeh Manheim, LCSW | 718.820.4919 WhatsApp +1 (929) 235.8530 aryeh.manheim@touro.edu lcm.touro.edu LANDER COLLEGE FOR MEN WITH TOURO’S

shortcomings I had witnessed. He then asked me whether I had raised these concerns with the supervising rabbi. I had not. Rav Nota told me, in no uncertain terms, that I was responsible to call the rabbi and note to him what I had seen that was subpar.

On his next visit to Buffalo, Rav Nota asked me what the rabbi had replied. I told him that I had been remiss in calling. To this, Rav Nota replied: “You have a responsibility to tell him that there is a problem. Whether he does anything about it is his issue, but that does not take away from your responsibility.”

In one case, a woman, married in an Orthodox ceremony, had remarried (without obtaining a get) and borne a child from the second marriage—a serious question of mamzeirus. When I shared with Rav Nota a halachic approach that perhaps might save this child from being a mamzer, he did not answer. This was his way of demonstrating that he felt the approach was not halachically correct. A while later, he said to me, “The next generation’s Rav Moshe will need to answer this she’eilah.”

Rabbi Yirmiyohu Kaganoff Jerusalem, Israel

A recent Jewish Action issue included a superb essay entitled “OU Kosher: The Inside Story.” Rabbi Menachem Genack’s historical insights are cogent, particularly the differences in the kosher consumer of yesterday compared to today.

I lived with my grandparents growing up. I still remember my grandmother kashering meat in the kitchen.

We have, under Rabbi Menachem Genack’s inspired leadership, made great strides over the decades. The OU and Jewish Action provide tremendous leadership to the observant Jewish community.

Dr. Steven Huberman Founding dean emeritus and professor of social work administration

Touro University Graduate School of Social Work New York, New York

NAVIGATING WIDOWHOOD

I’ve been enjoying the informative articles in the spring 2023 issue and appreciate your coverage about widows and widowers (“Navigating Widowhood in the Frum Community,” by Merri Ukraincik) and others in the frum community who unfortunately go off the community’s radar. We need to remember everyone in our community. Yasher koach to Jewish Action for highlighting this. Keep up the good work!

Rachel Steinerman

Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania

I cannot fully express my loneliness after losing my husband, my best friend. I have not been to shul since he passed away months ago. None of those who davened with my husband

reached out to me. I feel I have no place. I went away for Purim and came back to an empty house. No one left mishloach manot at my door.

Rabbis should be calling the almanos of their shuls on a regular basis to ask how they and their families are. We all need chizuk, and we need to know that people care.

A widow

Merri Ukraincik’s article about widows and widowers in the frum community was great. The interviews were eye-openers. I had thought of myself as a hard person, but now I realize that it was just a way to cope with what is, at times, a lonely way of life.

Miriam Ravitz Edison, New Jersey

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

To send a letter to Jewish Action, e-mail ja@ou.org. Letters may be edited for clarity.

4 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5783/2023

Summe 5783/2022 Vol 83, No 4

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

ZIONISM

our hearts still broken by the losses of so many Jewish soldiers and terror victims, including too many recent and raw losses, we gathered to express our gratitude to Hashem for the blessing of being in Israel, in Yerushalayim. And to pray for peace and redemption.

seventy-five years old and the strongest country in the Middle East?

By Mitchel R. Aeder

Ihad the incredible zechut (and also the zechus!) to spend Yom Ha’atzmaut 75 in Yerushalayim. As the wrenching sadness and stoic determination of Yom Hazikaron faded and the mood brightened, I joined thousands (literally) at an exhilarating and uplifting musical Tefillah Chagigit sponsored by OU Israel. Yom Ha’atzmaut is such a special—and complicated—day. With

And yet, there is dissonance. I live in New York. Am I an impostor, an outsider, a voyeur on Yom Ha’atzmaut—especially in Israel? However often I visit, I am a visitor. I consider myself to be a Zionist. Here are my Zionist bona fides: I was a member of a Zionist youth group while in high school. I spent a summer working on a kibbutz. My shul recites Hallel on Yom Ha’atzmaut and Yom Yerushalayim (without a berachah). I still get misty-eyed when I hear the haunting ballad “Yerushalayim shel Zahav.” I attended ulpan twice. Three of my children have made aliyah. I buy blue-and-white cookies for my children and grandchildren.

And yet . . . I live in New York.

Let’s put “Zionism” to the side. I submit that when it comes to our relationship with the State of Israel— not any particular party or politician or policy, but its very existence—we actually agree much more than we disagree. Here is a partial list of propositions about which I suspect there is something of an American Orthodox Jewish (dare I say?) consensus:

1. We care deeply about Israel (whether we refer to it as Israel or Medinat Yisrael or Eretz Yisrael). We follow the politics and other goings-on there closely, often more closely than we follow the news about the US. We grieve when there is a terrorist attack. We send money.

2. We have strong opinions about what happens in Israel, even though we do not have a vote.

This article is dedicated to the memory of my father-in-law, Dr. Jaime Sznajder, a”h, who passed away this Yom Ha’atzmaut. Grandpa loved all Jews, from Bundists to Satmar Chassidim. He was a passionate Zionist who had a close relationship with the late chief rabbi, Rabbi Shlomo Goren, zt”l. Yehi zichro baruch.

Alas, Zionism is a trigger word for so many, both within and outside of our community.1 Pre-1948, Zionism was a fault line between different political, economic and religious factions within the Jewish community. Among leading Orthodox rabbis, there were sharply divergent views about the appropriateness of establishing a state. Within Israel, these divergences persist and manifest in important political, tribal and cultural differences that impact on identity.

Zionism in Israel is tied up with identity and politics. But what does it mean to be a Zionist who chooses to live in the United States and not in Israel? And what does it mean to be a non-Zionist when the State of Israel is

3. We are very happy and grateful to Hashem that Israel exists, however flawed its founders and current leaders may be.2 We do not think the Jewish people and the dissemination of Torah would be in a better place had “Palestine” been governed for the past seventy-five years by the Turks, the British or the Jordanians.

4. We are very happy and grateful to Hashem that Israel has a strong army and defense force that are far superior to those of its neighbors. We believe the physical security of Israel is provided by Hashem, and Torah and mitzvot are crucial in this regard, while our hishtadlut requires a strong army, weaponry and technology as well. These beliefs do not preclude us from debating, from the comfort of our

5 Summer 5783/2023 JEWISH ACTION

Mitchel R. Aeder is president of the Orthodox Union.

DEEPLY ROOTED VALUES THAT MOVE HISTORY FORWARD

For more than a century, Yeshiva University has educated our children and grandchildren, our teachers, Rabbis and communal leaders. The influence and impact of YU’s Roshei

Yeshiva, professors and faculty prepare the next generation of leaders with Torah values and market-ready skills to achieve great success in their personal and professional lives—to transform our communities and the entire Jewish world for the better.

We have set an unprecedented goal of raising $613 million over five years—the largest campaign for Jewish education in history—for scholarships, facilities, and faculty that will further expand YU as the flagship Jewish university for generations to come. Now is the time to honor your past and invest in your future

RISE UP The Campaign for 613

Join us today at riseup.yu.edu

Science & Technology THAT MOVE HISTORY FORWARD

Yeshiva University has been at the forefront of life-changing scientific and technological breakthroughs for more than a century. Through innovative programs and expanded initiatives, including Cybersecurity and Artificial Intelligence at the Katz School of Science and Health—and the newly designed Selma T. and Jacques H. Mitrani Tech Lab at the Stern College for Women— YU continues to prepare our children and grandchildren to achieve successful careers in leading companies while adhering to their Torah values.

We have set an unprecedented goal of raising $613 million over five years—the largest campaign for Jewish education in history—for scholarships, facilities, and faculty that will further expand YU as the flagship Jewish university for generations to come. Now is the time to honor your past and invest in your future. Join

Campaign

RISE UP The

for 613

us today at riseup.yu.edu

living rooms, the merits of Chareidi enlistment in the IDF.

5. The learning of Torah—for men, women and children—has flourished in Israel for the last seventy-five years both qualitatively and quantitatively. Many of us have studied Torah in Israel and/or have sent our children to study Torah in Israel. For many of us, Torat Eretz Yisrael (or the Torah we learned while in Eretz Yisrael) has propelled our religious growth more than any other factor.

6. We love to visit Eretz Yisrael. The Kotel, Kever Rachel and Ein Gedi would exist without a State of Israel, though I query whether we would have access to them. Everything built since 1948? Highly doubtful.

7. Our commitment to Israel is not conditional on the makeup of the government on any particular day.

8. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, we believe instinctively that the creation of the State of Israel has religious significance, even if we do not often think about this. The Shoah had religious significance, which we acknowledge on Yom HaShoah or Tishah B’Av. How could the return to Tzion of what now constitutes nearly half of world Jewry not be equally significant in Jewish religious history?3 Yes, some claim they know what that religious significance is, while others humbly demur and prefer to wait until Hashem reveals His plan. But significant it is.4

So what about Israel/Zionism do we disagree about so passionately? And I am speaking about Israel’s existence, not its internal politics and culture. Whether we culturally and hashkafically align more with Gush Etzion or Bnei Brak is not relevant to this conversation.

Yom Ha’atzmaut remains a flash point. Some of us celebrate and say Hallel to thank Hashem for the miracle of Israel’s existence and continued flourishing. Others cannot fathom adding to the religious calendar and changing nusach ha’tefillah for a day established by non-religious Jews, a day whose date shifts year to year

and whose celebration often clashes with the minhagim of the Sefirah period.5 The differences here are stark, but no more so than the differences in religious practice and customs between different communities, and these latter do not generate the same passion.6

If I am correct, then, American Orthodox Jews outside the Chassidic communities are in broad agreement about Israel 364 days a year. That’s not bad for Jews. For that one day, it would be wonderful if we could

To be a Zionist, or a non-Zionist, living in America in 2023/5783 is to live with dissonance. We love Eretz Yisrael, but our embrace is not complete . . . yet. We are more than visitors but less than full participants in this magnificent and complicated project of Jewish history. We are dreamers.8 V’techezenah eineinu b’shuvcha l’Tzion b’rachamim.

Notes

1. Of course, Zionism has been catnip for antisemites. Infamously, the UN in 1975 equated Zionism with racism, sparking massive demonstrations (of unity!) in New York and elsewhere and permanently staining the UN as an institution, even after the declaration was repealed.

2. The theological objection of Rabbi Yoel Teitelbaum, zt”l, of Satmar to the creation of a sovereign Jewish state in Israel before the advent of the Messianic era has not achieved wide acceptance outside of his community.

3. In 1949, Winston Churchill said: “The coming into being of a Jewish State in Palestine is an event in world history to be viewed in the perspective not of a generation or a century, but in the perspective of a thousand, two thousand or even three thousand years.”

4. Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm, z”l, objected to including “reishit semichat Geulateinu” in the Prayer for the Peace of the State of Israel as “spiritual arrogance” . . . “I prefer to view the events of our time as providential and not (necessarily) Messianic” (Seventy Faces: Articles of Faith, vol. 2 [New Jersey, 2002], p. 216).

all acknowledge that the other side’s position is not unreasonable, despite our strong disagreements. Something to work on.

And, as noted above, the word “Zionist” is a trigger.7 Those of us who identify strongly with Israel but who choose (choose!) to live in chutz la’Aretz should perhaps be a little more humble about using the Zionist moniker. And those from the other camp should perhaps acknowledge that there are a great many good Jews and Torah scholars among the “Zionists.”

5. A head of school once told me that the question most asked by prospective parents was whether the school said Hallel on Yom Ha’atzmaut. (Some of the parents strongly wanted the answer to be yes, others the opposite.) He shook his head in wonder that the school’s curriculum and educational philosophy were of less concern than what happens for ten minutes one morning in Iyar.

6. I attended a Shacharit minyan on Yom Ha’atzmaut this year where Hallel was recited with a berachah. At my Minchah minyan up the block, Tachanun was said.

7. An Israeli Chareidi rabbi who was speaking recently to an American audience was asked about aliyah. After waxing eloquent about the benefits (and some challenges) of living in Israel, he paused and said with a twinkle in his eye: “But don’t accuse me of being a Zionist. I don’t want to be kicked out of my own shul!”

8. See Tehillim 126:1.

10 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5783/2023

Heart.Works

Those of us who identify strongly with Israel but who choose (choose!) to live in chutz la’Aretz should perhaps be a little more humble about using the Zionist moniker.

PLEASE

VEGAN

r s

• •ALLNATURAL

READY TO EATIN

MINUTES

GLUTEN FREE Heart.Works

Plantbasedslide

Meet Heaven & Earth’s Plant-Based Falafel Sliders: made with Organic Chickpeas and packed with flavor. These better-for-you burgers are a healthier lunch or quick dinner for this summer season. Mmmm, it’s Heaven!

FROM THE DESK OF RABBI MOSHE HAUER

THE GIFT OF ISRAEL

been restored to our Land and our Land has been restored to us.

True gratitude requires recognition and appreciation of every dimension of the gift. That recognition allows us in turn to utilize the gift to the fullest, as well as to identify and navigate its associated challenges. Toward that end, we need to consider what we have gained from our return to Eretz Yisrael and from the creation of Medinat Yisrael.

By Rabbi Moshe Hauer

Shehecheyanu v’kiymanu v’higianu lazman hazeh, latkufah hazot, lamakom hazeh

We are a blessed generation, living the dreams and prayers of millennia. Seventy-five years ago, the State of Israel was declared as a Jewish homeland on our ancestral holy land. Since that time, that besieged and impoverished State of 600,000 has grown to become the home of a near majority of the Jewish people; it’s an active and vibrant spiritual center and a hub of industrial, scientific, agricultural and economic innovation for the world. While we mark this milestone in the dark shadows of profound internal strife and external threats, we must not fail to express our deepest gratitude to G-d for the unique privilege of living in this period of history in which we have

Maharal of Prague1 observed that galut, the exile of the Jewish people, includes three principal negative components: national subjugation, dispersion and dislocation from our home. Rabbi Yehoshua Hartman2 insightfully notes that these elements are included in the blessing we recite in the daily Amidah prayer in which we ask G-d to end our exile: “Sound the great shofar of our liberation (from subjugation), raise the flag that will unite our exiles (from dispersion), and gather us (from dislocation) to our Land from the four corners of the earth.” Each of these three elements has deep and visible contemporary resonance, and each represents a component of the opportunities and challenges that lie ahead.

that drove the United Nations to grant our people a place of refuge. The thousands who arrived in Palestine to escape Russian pogroms and persecution before and after the turn of the twentieth century became the more than one hundred thousand who arrived in the State of Israel from the DP camps in Europe. Jews persecuted and made unwelcome in their countries of residence now had a place that would unconditionally welcome them home. The Law of Return codified this dimension of the State of Israel, granting immediate citizenship to any Jew who asked for it. Millions did, coming in waves from North Africa and the Middle East, Argentina and France, Ethiopia and the Former Soviet Union. The Law of Return was in a sense expanded by the heroic Entebbe rescue operation in July 1976, which demonstrated the principled commitment of the State to the safety and the rescue of Jews everywhere, not only allowing them to return but also bringing them home.3

As North American Jews who tend to view aliyah as an expression of idealism, we must not lose sight of the lifesaving and liberating role the State of Israel has played, recognizing that it is this form of aliyah that has been numerically dominant in the story of the modern return to Zion.

CHEIRUTEINU/LIBERATION: PROVIDING REFUGE

While the initial seeds of our return to Zion were rooted in a love for the Land, the driving forces in the creation of the State were antisemitism and the Holocaust. It was antisemitism that moved Herzl to create the Zionist movement, and it was the Holocaust

KIBBUTZ GALUYOT/UNITY: POWERING JEWISH IDENTITY

Israel has been a significant unifying force in Jewish life. We can never cease to be amazed by the literal ingathering

12 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5783/2023 Sleep

Rabbi Moshe Hauer is executive vice president of the Orthodox Union.

1. 2.

Upscale. On Sale. ON INSTAGRAM @THECLOSEOUT VISIT US AT ONE OF OUR CONVENIENT LOCATIONS: BORO PARK 4518 13TH AVE. 718.854.2595 WILLIAMSBURG 801 BEDFORD AVENUE 718.879.8751 CEDARHURST 134 WASHINGTON AVE. 516.218.2211 LAKEWOOD TODD PLAZA 1091 RIVER AVE (Route 9) 732.364.8822 OR PLACE YOUR ORDER ONLINE AT THECLOSEOUTCONNECTION.COM DOWN ALTERNATIVE COMFORTER SUPER SOFT 100% POLYESTER FIBER FILL ULTRA 100% COTTON FABRIC 300 THREAD COUNT HYPOALLERGENIC MACHINE WASHABLE DOWN LIKE FEEL BAFFLE BOX CONSTRUCTION AVAILABLE IN ALL SIZES Sleep in a cloud Internet prices may vary Twin Deep Slumber

Pad Aristocrat Pillow Sweet Slumber

Bliss

Deep Slumber Pillow

Mattress

Comforter Twin

Comforter Twin

of the exiles from all four corners of the earth that we encounter in any visit to an Israeli market, hospital, prayer service or Knesset subcommittee. But it goes far beyond that.

On the day that King Solomon built the Beit Hamikdash, he defined it as the place toward which Jews everywhere would direct their prayers. “That you will hear the pleas of Your servant, of Your people Israel, that they shall pray via this place.”4 Jerusalem, the city that binds us all together, k’ir shechubrah lah yachdav, 5 became the tel talpiyot, the hill toward which all mouths turned in sincere prayer.6 Every synagogue in the world is built with an orientation that places the holy ark on the front wall such that it directs the congregation in prayer toward the unifying spiritual center of the Jewish people, the Temple in Jerusalem.

In contemporary Jewish life, the unifying power of the Land and the State of Israel has become even more tangible.

In an oft-quoted comment, Rabbi Saadia Gaon declared in the twelfth century that “it is only through the Torah that our nation is a nation.”7 This is an unchanging truism that describes what has enabled Jews to survive as a people throughout millennia of exile and dispersion in foreign lands. We took the Torah with us wherever we went, rejoicing in its study and disciplined in its observance, thereby maintaining our distinct identity. But that commitment to Torah has weakened significantly over the past two centuries as Jews throughout the exile have become increasingly alienated from Torah knowledge and observance. Given that tragic reality, how would the Jews—the people whose nationhood is realized only through the Torah—survive as a people?

G-d in His ultimate kindness and visible providence provided the solution in the form of the renewed national interest in the Land of Israel. As Rabbi Yitzchak Yaakov Reines, the founder of Religious Zionism, wrote, the Zionist movement helped people who were running from their identity as Jews to instead embrace it.8 This phenomenon has continued visibly

since the founding of the State, as for the vast majority of Diaspora Jews it is not Judaism but the State of Israel— both concern for its safety and pride in its accomplishments—that has united and galvanized them as Jews and served as the most effective anchor of their Jewish identity. In a pragmatic sense, it appears that G-d’s interim solution to the challenge of assimilation and the preservation of Jewish identity was the creation of the Jewish State.9

The critical role of Israel in forging Jewish identity is underscored in the

The State of Israel’s role in strengthening the Jewish identity of Diaspora Jews was acknowledged and formally codified in the Nation-State Law adopted by the Knesset in 2018. There it is declared that “the State shall act in the Diaspora, to strengthen the affinity between the State and members of the Jewish People,” and “the State shall act to preserve the cultural, historical, and religious heritage of the Jewish People among Jews of the Diaspora.”12 While during the first decades of the State, Israel’s survival was significantly dependent on material and political support coming from Diaspora Jewry, today the situation is somewhat reversed as the Jewish identity of large segments of Diaspora Jewry depends on the State. Racheim al Tziyon ki hi beit chayeinu

most practical sense in the TaglitBirthright Israel project. This effort targeting young adults takes them to Israel for ten days of immersion in the Jewish story and exposure to Israelis and Israeli life. The project has broadly united the organized Jewish community, which sees it as an effective tool to enhance the Jewish identity of those who are not ready to make a significant personal commitment to Judaism. Birthright trips are not just a nice idea. In the two decades of their existence, studies have shown that Jews who participated in Birthright Israel trips were more likely than peers who applied but did not participate, to marry somebody Jewish, feel a deeper connection to Israel and observe Jewish holidays.10 These statistics are elevated significantly for MASA programs that provide a variety of extended immersive Israel experiences.11

This notion should not only be a cause for gratitude and part of our expression of appreciation for the gift of Israel. It must also guide our behavior, our communications and our policies. Preserving that sense of identity between Diaspora Jewry and the State of Israel is a paramount responsibility that both Israeli and other Jewish leaders must have top of mind. And while it would be self-defeating to compromise elements of the State’s Jewish character for this purpose, sensitivity in communication and in implementation of policies can go a long way toward maintaining Diaspora Jewry’s essential bond and identification with Israel.

3.

L’ARTZEINU/TO OUR LAND: BUILDING A JEWISH STATE

A complete Jewish life can only be achieved in the redeemed Land of Israel.13 This is not only due to the inapplicability of the Land-based and Temple-based mitzvot outside of Israel, but because when we live under the authority of other nations, the societal environment, character, values and laws are defined by those others. In that context, the most Jews and Judaism can hope for is the freedom to practice our faith within the narrow confines of

14 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5783/2023

. . . it appears that G-d’s interim solution to the challenge of assimilation . . . was the creation of the Jewish State.

TOURO TO THE NEXT STEP TAKES YOU

What are your sights set on—medical school, dental school, pharmacy school?

Ambitious students like you need a university that can get you where you want to go—in an environment that shares your values. With preprofessional tracks and career guidance, Touro can take you there.

touro.edu

religious and ritual study and practice. In our own land, however, we can create a holistically Jewish state, with an environment, character, values and laws that are informed by our own texts and traditions.

This does not imply religious coercion, but rather investment of Jewish and religious character. There is a power to living in the land of our ancestors, speaking their language, and being surrounded by landmarks, institutions and even street signs that tell the Jewish story. There is a richness to living in a society where the rhythm of the calendar of civic and professional life is set by Shabbat and yamim tovim, and where the lyrics of the popular music are derived from Biblical verses. There is a force to being part of a country that assumes responsibility for the material safety of Jews everywhere in the world, while nurturing within its own borders an astounding renaissance of Jewish learning and living. And there is depth to being part of a body politic where the moral and legal debates in the legislature, courts, hospitals and military draw upon Jewish sources for their resolution.

The Jewishness of Israel is of value even as we acknowledge that Judaism in the modern State does not have the final word on any of these issues. The

State of Israel is not a theocracy, and even the government’s most religious members—whether from the Chareidi or Religious Zionist parties—are politically libertarian and do not seek to compel individual halachic observance, while understanding that on questions of law and values the State’s legislature and courts will consider Western values alongside the religious. Nevertheless, since its inception the State has upheld its public religious character in the manner of traditional Orthodoxy, promoting this at times by law, as in the case of public transportation on Shabbat, and at times by popular consent, as in the case of the universal and voluntary abstention from driving private automobiles on Yom Kippur.

OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES

While each of these three dimensions represents an aspect of the outstanding gift that is Israel, these very same issues intersect with each other in ways that have created fundamental and even existential challenges for the State.

l For decades, world Jewry has debated whether halachic Jewishness—in the form of maternal ancestry or Orthodox conversion—should determine eligibility for the Law of Return, or whether the law should be more liberally applied to anyone who could be subject to persecution due to their connection to the Jewish people.

l The ongoing debates over the Kotel revolve around the value of an embrace of Jewish religious pluralism in pursuit of Diaspora Jewry’s broader identification with the State versus the internal negative impact of that embrace.

l Finally, in the prevailing tense climate resulting from the growing numbers and power of the Chareidi and Religious Zionist populations, how do we promote the Jewish character of the State without stirring feelings and accusations of religious coercion?

As in all cases of competing values, even when we feel that we have clear answers to these questions, consideration of all the relevant values

moves us to approach the questions with greater sensitivity and nuance, allowing us the possibility of reducing, even if not eliminating, the necessary costs of these difficult choices. That is a worthwhile exercise.

The gift of our return to Eretz Yisrael along with the creation of Medinat Yisrael has given us so much to be grateful for. We need to proceed thoughtfully to maximize the benefits of this gift for each and every Jew and for Klal Yisrael as a whole.

Notes

1. Netzach Yisrael, ch. 1.

2. Ibid., Machon Yerushalayim ed., n. 47.

3. This principle was subsequently codified in the Basic Law: Israel—The Nation State of the Jewish People, 6a.

4. Melachim I 8:30.

5. Tehillim 122:3.

6. Berachot 30a.

7. Emunot v’Deiot 3:7.

8. Ohr Chadash al Tziyon, Introduction, pp. v-vi.

9. Political philosopher Leo Strauss wrote the following in a letter to the editor in the January 5, 1957 issue of National Review: “The moral spine of the Jews was in danger of being broken by the so-called Emancipation which in many cases had alienated them from their heritage, and yet not given them anything more than merely formal equality; it had brought about a condition which has been called ‘external freedom and inner servitude’; political Zionism was the attempt to restore that inner freedom, that simple dignity, of which only people who remember their heritage and are loyal to their fate, are capable… I can never forget what it achieved as a moral force in an era of complete dissolution. It helped to stem the tide of ‘progressive’ leveling of venerable, ancestral differences.”

10. https://scholarworks.brandeis. edu/esploro/outputs/report/JewishFutures-Project-Birthright-IsraelsFirst/9924144319601921.

11. https://www.masaisrael.org/wp-content/ uploads/2022/09/Israel-Immersion-Masapdf.pdf.

12. Basic Law: Israel—The Nation State of the Jewish People, 6b-c.

13. The Chafetz Chaim wrote an abridged Book of Mitzvot, including only those commandments and prohibitions that apply outside of Israel. His compilation included less than half of the mitzvot, 77 out of 248 positive commandments and 194 out of 365 prohibitions.

16 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5783/2023

There is a power to living in the land of our ancestors, speaking their language, and being surrounded by landmarks . . . that tell the Jewish story.

Centennial Spotlight

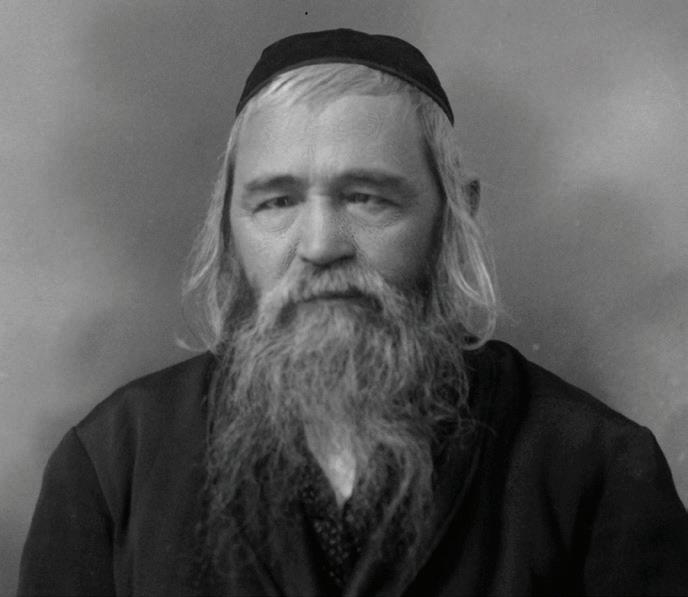

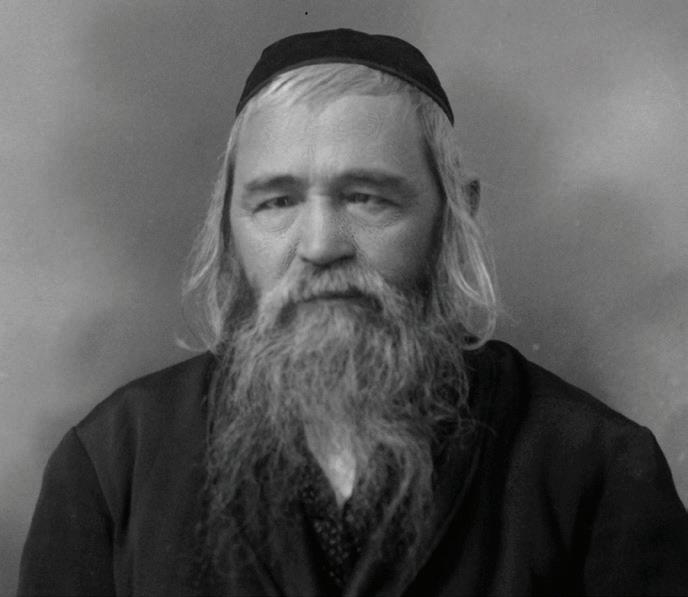

Rabbi Berel Wein

By Steve Lipman

Like any rabbi with thorough semichah training, Rabbi Berel Wein, a Chicago-born musmach of Hebrew Theological College (better known as “Skokie Yeshiva”), studied the required fundamentals of the laws of kashrut, particularly the Shulchan Aruch’s rulings on basar b’chalav (meat and milk). But he had no particular interest in working full time in the kashrut field.

In 1972, when he came from a pulpit position in Miami to New York City, becoming the OU’s executive vice president, he had no idea what the future would hold. Within months, Rabbi Alexander Rosenberg, the legendary rabbinic administrator of the OU’s Kosher Division, passed away. “Suddenly,” without warning, says Rabbi Wein.

Descending from a line of distinguished Hungarian rabbis, Rabbi Rosenberg, with his meticulous and uncompromising image, had modernized and shaped the Division for twenty-two years and was considered irreplaceable.

The OU and the Rabbinical Council of America (RCA) turned to Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik and asked for advice as to who would be the best candidate to assume Rabbi Rosenberg’s position, recalls Rabbi Julius Berman, a former OU president and longtime OU lay leader who was a close talmid of the

Rav. The Rav agreed that Rabbi Wein should take over the reins of the Kosher Division, which had an office staff of three people at the time. A lay leader of the OU told Rabbi Wein that if he took on the leadership of the kashrut arm of the agency, he “would save the OU,” remembers Rabbi Wein.

Rabbi Wein agreed and served as rabbinic administrator of the OU’s Kosher Division until 1977. “I knew I would do a good job,” says the rabbi, who had a law degree (from DePaul University) and legal experience that he would put to good use as a kashrut administrator. His previous experience as a mashgiach at hotels and at OUsupervised food producers in Miami also came in use, he says; he knew a kosher supervisor’s job from a microlevel, on-the-ground perspective—in addition to the education he had received from Rabbi Rosenberg. Rabbi Wein had worked closely with Rabbi Rosenberg, who taught by example what being the head of a major Jewish organization’s kashrut division entailed. He learned from Rabbi Rosenberg the political, practical and not-soglamorous aspects of the job. One piece of advice from Rabbi Rosenberg made a deep impression on Rabbi Wein, recalls Rabbi Menachem Genack. A dispute had arisen about a certain matter, and Rabbi Rosenberg resolved it with the words, “Ober vos vil G-t—but what does God want?”

Working “24/7” in his new OU role, Rabbi Wein handled various negotiations, dealt with the RCA as well as the mashgichim at the OU, traveled quite a bit and was responsible

for myriad other duties—in short, he did everything that OU Kosher’s now-much-larger staff does. “He was the best man for the job,” says Rabbi Berman, “because of his personality and because he’s brilliant.” Plus he had a legal background. Rabbi Genack concurs with this assessment. “Rabbi Wein is well-known as a highly popular historian and rabbi, but less known is the fact that for a few years he made use of those same significant skills and talents to oversee the OU’s kashrut enterprises.”

Recalling the difficulties of those years, Rabbi Wein says, “ The challenge was to create an orderly, efficient and corruption-free organization in a field that still was chaotic and a little wild west. Everybody was on their own, forming their own kashrut organizations; there was no uniformity and there were many certifications that were questionable. The challenge was to set the standard.” Which the OU ultimately did.

Rabbi Wein is best known now for

18 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5783/2023

Steve Lipman is a frequent contributor to Jewish Action.

Special thanks to Toby Klein Greenwald for helping to prepare this article for publication.

With 2023 marking 100 years of OU Kosher, throughout the year, Jewish Action will profile personalities who played a seminal role in building OU Kosher.

establishing Congregation Bais Torah and Yeshiva Shaarei Torah in New York State’s Rockland County, for his subsequent series of popular books on Jewish history and as founder of the educational Destiny Foundation. But the rabbi, who made aliyah in 1997, says his biggest accomplishment during his five-year tenure at the helm of the Kosher Division was putting the OU “into the meat industry.” The owners of two meat-packing houses, whose kosher products were under the supervision of other kashrut agencies, approached the OU with an interest in switching to OU supervision, explains Rabbi Wein. He handled negotiations with the two businesses and with OU leaders, some

of whom were reluctant to add the meat industry—kosher slaughter and the other halachic requirements of kosher meat are much more complicated than those of dairy or pareve products— to the OU’s kashrut supervision responsibilities. The rabbi’s negotiations were ultimately successful. Since leaving the OU, Rabbi Wein has maintained his interest in kashrut, frequently giving public lectures and classes on the spiritual significance of keeping kosher. “The consumption of only kosher food has been one of the main contributors to the survival of Judaism and the Jewish people over the ages,” he wrote in an essay two years ago on the yeshiva.co website. “It has

given us a deep realization that being a Jew relates also to the body and internal organs of a person, and not only the cerebral notion of religion that many people have.

“Difficulties in maintaining proper standards in kosher food and the abandonment by many secular Jews of the entire concept of kosher food,” continued the rabbi, “have inevitably contributed to the rates of assimilation and intermarriage of their succeeding generations. One of the great blessings of our modern time is the abundance of all types of kosher food.”

Rabbi Wein’s kashrut work at the OU helped make kosher observance more extensive, says Rabbi Moshe Elefant, COO of OU Kosher. “The world of kashrut when he came [to his new position] was very different from the world of kashrut today.”

“When Rabbi Wein served as the rabbinic head of OU Kosher,” Rabbi Elefant says, “the world didn’t realize how important kashrus was.” With his skill set, “he was instrumental in making kosher [food] accessible to many people.”

19 Summer 5783/2023 JEWISH ACTION

“IF YOU REALLY CareD ABOUT ME, YOU WOULD...” ? A Normal dating overture C Red flag B Proceed with caution D Maybe I should speak to someone? Our trained advocates are standing by, waiting for your call. We are here for you. You are not alone. And you don’t even have to say your name.

CONFIDENTIAL HOTLINE CALL. TEXT. WHATSAPP. Abuse can occur at any stage of life –To anyone, in any form. Shalom Task Force replaces heartache with hope THE choice IS YOURS.

‘There was no uniformity and there were many certifications that were questionable. The challenge was to set the standard.’ Which the OU ultimately did.

888.883.2323

TAKING CHARGE

YOUR of HEALTH

By Rachel Schwartzberg

Routine blood work for health insurance came as a wake-up call for Amanda back in 2019. The results showed she was pre-diabetic. “I was scared,” she recalls. “I was too young to feel my best years were behind me.”

At the time, she was thirty-three years old with three small children—and a family history of diabetes. “I knew I had to do something. There would never be a perfect time to deal with it; life wasn’t going to slow down.”

Amanda implemented changes to her eating and other habits, and increased her activity. She was gratified to see an improvement in her numbers within six months. “My body started to say thank you,” she says. “I had more energy. I showed up better as a mom and as a wife.”

With continued effort, Amanda lost nearly sixty pounds—but she appreciates most what she gained in the process. “I learned that nothing would change if I didn’t take ownership of my own health,” she says. “I’m breaking a generational cycle [of unhealthy habits].”

She notes that with two additional pregnancies in the intervening years, while she hasn’t kept off all the weight she lost, prioritizing her health is a journey that has positively affected her family.

20 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5783/2023 HEALTH AND WELLNESS

For Joint

If you suspect you or a loved one has Gaucher disease, speak to your doctor or call The National Gaucher Foundation toll free at 800.504.3189. Schedule a call to speak with our Medical Director, Dr. Robin Ely, NGF Founder.

it

SOMETHING’S NOT RIGHT. For more information, visit gaucherdisease.org/mysymptoms Could

be Gaucher Disease? Gaucher disease TYPE 1 is a rare genetic disorder that is easily detected with a blood test. It is more prevalent in the Ashkenazi Jewish community, but is not life-threatening and is not included in some Jewish genetic screenings. Once diagnosed, Gaucher disease can be treated with medication.

Easy Bruising Nose Bleeds Bone & Joint Pain Enlarged Liver and/ or Spleen

With all the pressures that come along with leading a frum life, preventive health care often takes a back seat, according to the directors of JOWMA, the Jewish Orthodox Women’s Medical Association, which provides free health education to the Orthodox Jewish community. Many people are lax about taking care of their health, from cultivating healthy habits to staying on top of routine doctor visits and medical screenings.

“In general, the Orthodox Jewish community is really good at reacting,” says Dr. Jennie Berkovich, a Chicagobased pediatrician who serves as JOWMA’s director of education. “When someone is sick, we’ll get referrals to the top specialists and stop at nothing to get the best care.” But, she adds, when it comes to preventing illness in the first place, “it’s hard to prioritize.” In her role at JOWMA, she dedicates her time to educating the Jewish community about how to make good decisions when it comes to health. JOWMA is part of the fourth cohort of the OU’s Impact Accelerator, a program that helps advance promising Jewish nonprofits.

Admittedly, says Dr. Berkovich, this is not a uniquely Jewish issue. In fact, the US Department of Health and Human Services has launched the “Healthy People 2030” initiative to encourage millions of Americans to get recommended preventive health care services that will reduce their risk for diseases, disabilities and death.

Dr. Berkovich says that when it comes to well visits at the doctor, most people are good about bringing in babies. “After that, the trends show parents bring kids to the pediatrician in years when schools require paperwork,” she explains. “Then we often stop seeing adolescents and college students unless something is wrong.”

As adults, women often visit an obstetrician/gynecologist regularly, whereas men may not see a doctor until they have symptoms they can’t ignore. “In general, there is a feeling that men are not as attentive to routine medical care as women,” says Elana Silber, CEO of Sharsheret, a national organization supporting Jewish women with cancer.

As a starting point, Dr. Berkovich recommends that everyone establish a good relationship with a primary care provider. “The PCP relationship is critical for preventive health care,” she says. “There is value in the routine

exam because symptoms often start when a disease has already progressed. An earlier diagnosis typically leads to a better outcome.”

ARE WE GETTING ENOUGH SCREEN TIME?

Although people may not be visiting their doctor as often as they should, when it comes to getting recommended medical screenings, the Orthodox Jewish community is doing a pretty good job, according to Silber. “We’re seeing women taking the lead and getting annual mammograms after age forty,” she says. “Unfortunately, Covid slowed that down, but we at Sharsheret are reminding people to continue.”

In addition to routine screenings, Silber recommends that people understand their family medical history, which may point toward other preventive measures. “Someone is at greater risk if a family member has had cancer,” she explains. Silber notes that “people can definitely be afraid” of facing these issues. “But we are very fortunate in this country to have excellent medical care. If you’re proactive, you can prevent cancer or catch it when it can be cured.”

Sharsheret, which is based in Teaneck, New Jersey, educates and

22 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5783/2023

With all the pressures that come along with leading a frum life, preventive health care often takes a back seat.

Rachel Schwartzberg is a writer and editor who lives with her family in Memphis, Tennessee.

The Pathways Early Assurance Program allowed me to secure a seat in a very competitive program in my junior year.

Start planning for your future today.

Accelerated Dual Degree

B.S./M.S. in Accounting

B.A./M.S. in Artificial Intelligence

B.A./M.S. in Biotechnology Management & Entrepreneurship

B.A./M.S. in Cybersecurity

B.A./M.S. in Data Analytics & Visualization

B.A./M.S. in Digital Marketing & Media

B.A./M.A. in Holocaust & Genocide Studies

B.A./M.S. in Jewish Education

B.A./M.A. in Jewish Studies

B.A./M.A. in Mathematics

B.A./M.A. in Mental Health Counseling

B.A./M.A. in Physics

B.A./M.S.W. Master of Social Work

Health Sciences Early Assurance

Occupational Therapy Doctorate

M.S. in Physician Assistant Studies

M.S. in Speech-Language Pathology

yu.edu/pathways

Sarah G. Katz School of Science and Health

Physician Assistant

guides women about genetic risk factors and how to access testing and understand their results. “As many as one in forty Jews—women and men— carry the BRCA gene mutation,” says Silber. This is especially significant among Orthodox Jews, who tend to marry within the community, perpetuating genetic mutations.

Silber notes that with some prophylactic surgeries, there is close to a 100 percent success rate of not developing cancer—which is especially significant for diseases like ovarian cancer that can be hard to catch early. “Where it’s talked about, women are taking these proactive measures,” she says. “Families who have seen a family member suffer are more likely to get tested and take action.”

Sharsheret encourages women to be proactive in learning what steps they can take to preserve their health. One of the challenges, Silber explains, is that the medical community has information and new modalities, but

they’re not out there marketing it to regular people. Sharsheret tries to bridge that gap, getting the information out there and helping women navigate their options.

Silber wishes there was a greater sense of urgency about the topic in the Jewish world. “The cancers related to BRCA are plaguing our community.” But, she adds, “there are things people can do to save their lives now.”

According to Cleveland Clinic gastroenterologist Dr. Michael (Meir) Pollack, while genetic screenings are becoming more common, people often don’t know what to do with the knowledge they have been handed. “I’ve seen young people who come over to me with a printout, asking, ‘What do I do with this information?’” he says. “They now know there are 100 genes they’re carriers of, which might indicate they’re at higher risk for certain diseases.”

Dr. Pollack recommends that people who do these screenings have their

results reviewed by a professional. “It could save your life,” he says. He recalls speaking to a man in his thirties whose genetic test showed he was at higher risk of colon cancer. “He had no symptoms and no family history,” Dr. Pollack says. “I recommended a colonoscopy, but when I saw him a few months later, he hadn’t done it yet. He finally had the colonoscopy, and they found a malignancy.” Fortunately, it was caught at an early stage, and the man was completely cured.

Dr. Pollack notes that studies have proven that people of Ashkenazic Jewish descent are twice as likely to have Crohn’s or colitis—which in turn increases a person’s risk for colorectal cancer. However, he doesn’t see people from the Jewish community keeping up with medical recommendations at higher rates than the general population. “Most people know about getting a colonoscopy starting at age fifty,” he says. “However, current guidelines actually recommend doing

WHAT CAN WE AS A COMMUNITY DO TO ENCOURAGE BETTER HEALTH?

By Rachel Schwartzberg

Community-based organizations— like shuls, Hatzalah, Bikur Cholim, or Jewish community centers—can provide valuable education through lectures, seminars or health fairs.

“The frum community overall is sophisticated and worldly, but you’d be surprised how many people just aren’t aware of the basics and miss the chance to catch problems early,” says Dr. Michael (Meir) Pollack of the Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Jennie Berkovich, director of education for the Jewish Orthodox Women’s Medical Association (JOWMA), adds, “The value of these events is that community members want to hear this information from a source they’re comfortable with.” JOWMA offers content and curricula for such programs.

Jewish organizations should take advantage of opportunities—such as during months when specific health topics are trending—to remind people of the importance of screenings.

Day schools and yeshivot can improve the nutritional value of the food they serve to students. “Schools should work with a nutritionist to provide balanced meals that are appealing to children; protein and vegetables should be included, not just pizza and pasta,” says Dr. Hylton Lightman, a wellknown pediatrician in Far Rockaway, New York. Additionally, teachers and rebbeim would do well to consider prizes and incentives other than candy and cans of soda.

At a kiddush, event or simchah, hosts can make sure healthful food options are served. This could include fruit platters at a dessert buffet, and water or seltzer alongside the soda. “People may not want to eat certain foods and it’s difficult for them if there are no other options,” says health and fitness coach Chaim Loeb.

24 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5783/2023

Go to the go-to. SERVING TOWN SINCE 1979. LAKEWOOD 732-364-5195 10 S CLIFTON AVE., LAKEWOOD, NJ 08701 CEDARHURST 516-303-8338 EXT 6010 431 CENTRAL AVE., CEDARHURST, NY 11516 BALTIMORE 410-364-4400 EXT 2205 9616 REISTERSTOWN RD., OWINGS MILLS, MD 21117 WWW. TOWNAPPLIANCE .COM Welcome to our Town! ALL BRANDS ALL MODELS ALL BUDGETS For 1000’s of customers. For nearly 50 years.

so beginning at age forty-five. And people don’t know that there are other tests that are less invasive that have been shown to be quite accurate.” So while 65 percent of people over fifty are getting colonoscopies, “that means 35 percent of people don’t do anything,” he says. “If they feel fine, they think they’re fine.”

Dr. Pollack worries that people are not aware of the long-term health ramifications of what they consider to be “normal” digestive discomfort. “You’ve got people popping Tums without thinking about it at all,” he says. “But over many years, chronic acid reflux is a risk factor for Barrett’s esophagus, which is premalignant,” he explains. “For people with chronic reflux, an upper endoscopy screening is recommended. Then we would check again every three years to make sure nothing’s changing.”

Overall, Dr. Pollack understands that people are busy and for various reasons—whether it’s laziness or poor insurance coverage— preventive screenings are neglected. “Unfortunately,” he says, “no one stops and says, ‘How can I preserve myself to live a long life in good health so I can continue doing the things I love to do?’”

KEEPING HEALTHY KIDS HEALTHY

Dr. Hylton Lightman, a pediatrician who has served the Orthodox Jewish community for more than forty years in his Far Rockaway, New York, practice, says his guiding principle is “prevention is better than intervention.”

He recommends regular well visits every year. “It’s important for a pediatrician to assess a child, not just physically but also their context,” he explains. “This allows us to understand what is going on for the child and to prevent later difficulties of the body.”

A significant step parents can take to proactively help their children remain healthy is staying up to date on vaccinations, according to Dr. Lightman. As a native of South Africa who practiced medicine in that country before coming to the US, he is especially dismayed that there are many people within the frum community who are reluctant to do so. “This is foolish and dangerous,” he says. “Vaccines are tools Hashem gave us to prevent disease. I’ve seen these diseases up close and they are debilitating and devastating,” he asserts.

Like many pediatricians, Dr.

Lightman has seen children become more sedentary and spend less time outdoors in recent years, in addition to growing rates of obesity among children. The increase in childhood obesity has been well documented in the general media. In fact, in January, the American Academy of Pediatrics released its first comprehensive guidelines for evaluating and treating children and adolescents with obesity. The recommendations were met with controversy, as they focus on weight loss as the best path to health and suggest putting children as young as age two on diets. For teens, the guidelines include weight loss medications and even bariatric surgery referrals.

Dr. Lightman strongly cautions people to be careful when encouraging weight loss in children. “As a society, we pay too much attention to appearance and weight, especially in females,” he says. Teens can develop eating disorders as a result. “We have to convey a message to our children of respect for our bodies and for each other,” he maintains.

In general, Dr. Lightman believes Orthodox parents are trying their best to do what’s right for their children.

26 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5783/2023

When I got to the end of the race, I cried. So many of us have a destructive inner voice saying, ‘Why bother doing this?’ I saw that I could go beyond my selfimposed barriers.

Continued from page 26

“But they are overwhelmed with the responsibilities of life,” he says. He stresses that adopting a healthy lifestyle is “absolutely imperative to the well-being of children and adults.”

WHAT’S EATING US?

According to Silber at Sharsheret, society in general is embracing the importance of healthy eating and exercise, thanks to both traditional and social media. “We’ve also seen significant reduction of tobacco use, which is amazing,” she says. Interestingly, Silber notes, “people seem less willing to eliminate alcohol” in response to medical recommendations.

Within the Orthodox community, however, experts note that certain factors in Jewish life contribute to unhealthy behaviors. “Our lifestyle focuses heavily on food,” says Dr. Berkovich of JOWMA. “We’re also largely sedentary. We walk to shul, but only on Shabbos—and then we try to ensure we don’t have to walk too far.”

Dr. Pollack agrees that frum society is hyper-focused on food. “This isn’t new; it’s part of our culture. Our ethnic Jewish foods are very fatty—cholent, kishka, kugel. Many of us enjoy these things at a kiddush and then come home and do it all again for lunch.” He stresses that it’s not bad

EXPERTS’ TIPS FOR HEALTHY LIVING

By Rachel Schwartzberg

Develop a good relationship with a primary care provider. “If you don’t feel good about your PCP, find one you like and make a point of going even when everything is fine,” says Dr. Berkovich.

Learn your risk factors, including family history. “Know your personal circumstances,” says Silber. “Being proactive could make a real difference.”

Get your recommended medical screenings, based on your age and other factors. “A colonoscopy isn’t fun,” says Dr. Pollack. “But don’t wait until it’s too late.”

Consider what’s in the food you eat and feed your family. “There are lots of foods, like yogurt, for example, that people think are healthy but which often have a lot of sugar,” says Dr. Lightman. He recommends checking the glycemic index of foods, as well as avoiding foods with extremely high sodium content.

Make sure you are drinking enough water. “I frequently see a lack of proper hydration,” says Dr. Lightman, which impacts so much of a person’s function.

When attending an event, consider in advance what foods you might want to enjoy or avoid. “When it comes to what we eat, if we invest no prior thought or intention, we tend to make worse choices,” says fitness coach Chaim Loeb.

Make time for physical activity in your schedule. “When I meet a patient, I can tell who is active and who isn’t,” says Dr. Pollack, “because it makes a difference.” Additionally, children should be encouraged to play outside and be as active as possible. “Children are on devices starting at a very young age, which precludes active play,” says Dr. Lightman. Even something as simple as taking a family walk for ten minutes can be beneficial.

28 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5783/2023

to enjoy any particular food, but “everything in moderation.” Dr. Pollack feels this is “the biggest issue” plaguing the Jewish community when it comes to health. “Screenings? Yes! But what’s killing our people is obesity,” he says. “Obesity is a risk factor for cancer, heart disease and stroke.”

In addition to poor eating habits, a lack of physical activity compounds the issue. “I don’t know if Orthodox Jews tend to have a more sedentary lifestyle than anyone else in 2023,” notes Dr. Pollack. “But many are busy with families, work, carpools, errands, hosting, et cetera, and we don’t prioritize our health. Then

suddenly, you’re sixty years old with big problems.”

Lifelong bad habits around food and activity—and the emotional baggage that goes with them—are common themes Chaim Loeb hears from his clients at Fit Yid Academy. Based in Phoenix, Arizona, Loeb offers virtual personalized coaching to Jewish men who want to achieve fitness or health goals and learn how to sustain a healthy lifestyle. He has worked with approximately seventy men in the three years since he began Fit Yid Academy, with the majority of his clients in their thirties and forties. “The main thing I hear is, ‘I don’t have time,’” he says. “For most of us, fitness

and health are very important but not urgent. It’s hard to create time for it when we tend to live within the box of dealing with what’s urgent.”

Loeb adds that he sees a common “all-or-nothing” perspective among Orthodox men. “We have to teach people to work on consistency over perfection,” he says. “Plus, people want quick fixes. But our goal should be to build regular habits, which takes time and effort.”

He says he gets calls from men who were told by a doctor they’ve got certain risk factors or are headed in a certain direction. “Unfortunately, most people who hear this do nothing,” he says. But joining a gym or an

29 Summer 5783/2023 JEWISH ACTION

I don’t know if Orthodox Jews tend to have a more sedentary lifestyle than anyone else in 2023,” notes Dr. Pollack. “But people are busy with families, work, carpools, errands, hosting, et cetera, and we don’t prioritize our health. Then suddenly, you’re sixty years old with big problems.

exercise program or signing up with a coach can lead to significant improvement. “We’ve seen real changes in [people’s] numbers. It’s beautiful.”

When it comes to eating, Loeb avoids referring to foods as “bad or “good”—or even “healthy” or “unhealthy.” What we eat, he says, can be either “supportive or not supportive of our personal goals for our well-being.”

For Rabbi Aryeh Markman, executive director of Aish LA, being physically fit is part of avodat Hashem. “I once heard that there is a lot of spirituality in being a healthy human being,” he says. “It allows us to do more. We want to be able to build our sukkah, clean for Pesach, fast on fast days and even get our grandchildren out of their car seat without pulling out our backs.”

While he has always considered himself to be in shape, Rabbi Markman ran his first half marathon with RabbisCanRun in 2019 in Jerusalem. “When I got to the end of the race, I cried,” he recalls. “So many of us have a destructive inner voice saying, ‘Why bother doing this?’ I saw that I could go beyond my self-imposed barriers.”

RabbisCanRun was founded in 2017 by running enthusiast Meir Kaniel to enable rabbanim to improve their health and inspire others. Participants train for and run their first 10K, half marathon, or full marathon race. Roughly eighty-five rabbis, from communities across North America and Israel, have participated to date.

Rabbi Markman, who has since run several marathons, truly believes anyone can find a way to become more active that works for them. “It’s like anything you do in Torah,” he says. “Learning five minutes a day is going to impact your life; you’ll grow as a person. Similarly, incorporating some exercise into your day will help your body improve for the better.”

One of the unexpected side benefits of his longdistance running was seeing how his commitment has affected his entire family, Rabbi Markman notes. “My children were encouraging,” he says. And his wife began exercising too. “My working out gave her ‘permission’ to take the time out of her own busy schedule to make her health a priority,” he says.

Similarly, Amanda, who lost sixty pounds during her pursuit of health, has been thrilled to see the ripple effect of her efforts. “My husband was always supportive of my health journey,” she shares, “but I always felt like I was on my own.” While she worked hard to change her lifestyle, her husband kept up his “poor habits,” she says, which eventually led to high cholesterol and foot pain. “This past year, he made some conscious changes on his own. The pain went away, and he got his cholesterol numbers down without medicine.”

Knowing that she’s being a role model for her own family has made her efforts to embrace a healthier lifestyle all the more worthwhile. “There are still challenges along the way,” Amanda says, “but there’s no going back to how things were.”

As we prepared to go to press, we heard the distressing news of the passing of our literary editor emeritus,

Widely respected as a brilliant thinker and talmid chacham, Rabbi Greenblatt, a talmid of Rav Yitzchak Hutner, zt”l, and a lifelong friend of Rav Aharon Lichtenstein, zt”l, had an immeasurable impact on Jewish Action. For more than three decades, his vision, intellectual breadth and unrelenting determination helped mold the magazine and set a standard of excellence in the world of Orthodox publishing.

A tribute to Rabbi Greenblatt will appear in a future issue.

30 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5783/2023

Summe 5783/2022 Vol 83 No 4

RABBI MATIS GREENBLATT, z”l.

ISRAEL AT 75

Reflections on the founding of the Jewish State

Rabbi Yehuda Amital

Rabbi Eliyahu Dessler

Rabbi Tzvi Pesach Frank

Rabbi Yaakov Friedman

Rabbanit Miriam Hauer

Rabbi Dr. Yitzchak Isaac Halevi Herzog

Rabbi Yehoshua Hutner

Rabbi Yosef Shlomo Kahaneman

Rabbi Dr. Aharon Lichtenstein

Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer

Rabbi Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz

Rabbi Dr. Nachum Eliezer Rabinovitch

Rabbanit Puah Shteiner

Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik

Rabbi Yechiel Michel Tukachinsky

Rabbi Eliezer Waldenberg

Rabbi Berel Wein

Rabbi Dr. Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg

Rabbi Shaul Yisraeli

Rabbi Shlomo Yosef Zevin

THE MEDINAH: THROUGH A TORAH LENS

The establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 was such a profound event that no serious thinker could avoid contemplating the implications of this historic moment. There is obvious religious importance in the return of a form of Jewish sovereignty to a portion of the Biblical Land after nearly two thousand years of exile. How did a variety of great religious personalities respond to this? What follows is a series of brief profiles of, as well as personal reflections from, a limited selection of Torah giants, each of whom lived during the miraculous establishment of the Jewish State and responded positively in his own way.

Each one of these diverse thinkers has his own approach, with great nuance that cannot be discerned from a single quote or brief essay, and which sometimes evolved over time. This sampling of rabbinic thought offers us a glimpse into different ways of viewing the enormity and complexity of the events in a religiously positive light.

Rabbi Gil Student, Jewish Action book editor

By Rabbi Menachem Dov Genack

In general, the Rav’s thought, indeed his whole way of looking at the world, was marked by a dialectical approach, a never-ending effort to live with the tension of opposing poles of an issue. His attitude toward the State of Israel was no exception. Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik firmly believed that the State of Israel—the establishment of Jewish sovereignty itself—was a fulfillment of the mitzvah of yishuv ha’Aretz, a view that he attributed to the Ramban. Jewish destiny in Jewish

hands was, for the Rav, not merely the realization of a nationalist dream, but the observance of a religious imperative—yet he also emphasized the danger of nationalism divorced from religious underpinnings and criticized such tendencies within the religious camp as well.

The Rav made only one trip to the Holy Land, in 1935, when he was a candidate for the chief rabbinate of Tel Aviv. During his visit, he merited to see Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook, who was then in the last months of his life. Rav Kook made a deep impression on the Rav; he described Rav Kook as “a great religious personality—Judaism to him was not

32 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5783/2023

Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik (Pruzhen, Poland, 1903-Boston, Massachusetts, 1993)

ISRAEL AT 75

The Rav believed the State of Israel was the fulfillment of the mitzvah of yishuv Ha’Aretz. Courtesy of Yeshiva University Archives

an idea, it was a great experience, a passion, a love, it was a living reality . . . . When you read his books and his writings, it is like a stormy sea, like a powerful tide driving you to lands unknown.” Interestingly, I heard from Rabbi Avraham Shapira, the late chief rabbi of Israel, that Rav Kook told him to take advantage of the opportunity to attend the Rav’s shiurim, because hearing the Rav was like hearing his grandfather Rav Chaim.

The Rav shared the story of his visit to a secular kibbutz, ideologically located “on the border of Stalinism,” which, he was shocked to discover, maintained a kosher kitchen:

They told me the following incident,

which had taken place a few years before . . . Rav Kook came to the kibbutz for Shabbat . . . . On Saturday night, after he made Havdalah, they had a gathering and he began to dance with them. He told them stories about his past, about his father and mother, absolutely not indicating disapproval or censure about their behavior. On Sunday morning, he said to them: “Shalom, lehitra’ot, v’le’echol b’yachad seudah achat Farewell, and next time let us eat together at one table.” The next day, the dishes were thrown out and the kitchen was made kosher . . . . You ask what power he exerted? It was the power of his religious personality.

I believe that the Rav shared Rav

Kook’s optimism regarding the potential of the non-affiliated Jew in Israel to adopt a life of Torah. In his Chamesh Derashot, the Rav wrote: “By him watering an orchard in the Emek, the vitalizing dew of the Eternal One of Israel, the Creator of the Universe, also alights upon this seemingly disinterested non-believer. . . .” Yet the Rav’s Zionism differed qualitatively from Rav Kook’s ecstatic Messianic viewpoint. The Rav’s perspective was more dispassionate, seeing the State as part of G-d’s plan of counteracting the physical, psychological and emotional devastation of the centuries of Jewish persecution that culminated in the Holocaust, rather than as a Divine utopia foreshadowing

33 Summer 5783/2023 JEWISH ACTION

The Rav shared Rav Kook’s optimism regarding the potential of the non-affiliated Jew in Israel to adopt a Torah life.

the End of Days. Likewise, Rav Kook emphasized the quality of the Jewish people as a nation; the concept of a state fit well into his religious consciousness. The Rav, on the other hand, focused more on the individual; “the flight of the alone to the Alone,” a quote he borrowed from Plotinus, epitomized his view of religion. A key point for the Rav was his belief that Judaism in the Diaspora would not have been able to survive without the establishment of the State. “Were it not for the State of Israel,” he often said, “American Jewry would be wiped away in a tidal wave of assimilation.” The Rav was completely correct—Israel was crucial to maintaining American Jewish identity. (Sadly, much of American Jewry no longer possesses instinctive support for Israel, and it is being swept away by assimilation.) In addition, the Rav saw in the establishment of the State the refutation of the Catholic theological view of Judaism as a historical relic.

But the State also created the possibility for Judaism to be reinvigorated; only in a Jewish state could there emerge a rich, multidimensional Judaism. In a sermon from 1946 contained in the newly published book The Return to Zion, the Rav writes that only in Israel could Judaism be “transformed into an all-encompassing space—long, wide, and deep, with distant horizons and unending boundaries—in a word: a true worldview.” [See “The Return to Zion” on page 58.] I heard the Rav quote Rav Kook’s interpretation of the words we recite in Ne’ilah, “Lema’an nechdal mei’oshek yadeinu—that we may desist from the theft of our hands.” Why at the culmination of Ne’ilah do we pray to no longer commit theft? Rav Kook explained that our request is not about theft committed with our hands; it is that G-d accept our teshuvah so that we can desist from the theft of our hands themselves, of our potential. On a national level, I would add, it is the founding of the State that allows the Jewish people to desist from the theft of its great potential.

The Rav’s relationship with the State was multifaceted, as to be expected from such a complex thinker, but his attitude toward the State of Israel as the realization of a religious ideal was a constant in both his philosophy and his life.

34 JEWISH ACTION Summer 5783/2023

‘Were it not for the State of Israel,’ he often said, ‘American Jewry would be wiped away in a tidal wave of assimilation.’

David Ben-Gurion reading the Declaration of Independence in the Tel Aviv Museum on May 14, 1948. Courtesy of the Israel Government Press Office/Kluger Zoltan Let

Rabbi Menachem Dov Genack is CEO, OU Kosher. The Patriarchs. forget. place experience. hand their aspect very thanks enthusiasm.

The highlight for me was the Cave of the Patriarchs. My first visit and one I will never forget. Going back in time to visit such a holy place is emotional and a spiritual, enriching experience. To hear and understand first hand what the se lers lived through, and their determination to succeed, was an aspect of the tour I appreciated. The tour was very well organized and planned. Special thanks to Yaffa for her efforts and enthusiasm.

Jennifer L.

Really inspiring tour! Rabbi Simcha did an amazing job! He gets so into the stories that you feel like you were there, actually making you part of history!

David F.

David F.

This is an incredibly meaningful experience that is not to be missed. Rabbi Simcha Hochbaum is a one-of-a-kind person who makes Hebron come alive. You can feel history come alive through his explanations.

This tour was awesome!!! Rabbi Hochbaum is an excellent guide who brought the history to life as we walked in the footsteps of our forefathers and mothers as well as the many people who gave their lives al Kiddush haShem. This tour really made an impression. Even our 12 year old said it was “very cool and special”. I would highly recommend it.

Rivkie W.

We've been on this tour numerous times and always enjoy & benefit from it. This time we really appreciated the updated Beit Hadassa museum. It was really a moving experience. Can't wait to come back again!

Round-trip coach bus to Kever Rachel, Maarat HaMachpela and modern Jewish Hebron neighborhoods. Let us know if your child is celebrating a Bar/Bat Mitzvah so we can make their experience even more meaningful! Don’t take our word for it…see what everyone is saying about Hebron on TripAdvisor! HEBRONFUND.ORG TOURS: +972.52.431.7055 • OFFICE : 718.677.6886 • tour@hebronfund.org

Roshni2011

Visit the parents in ןורבח

Marci M.

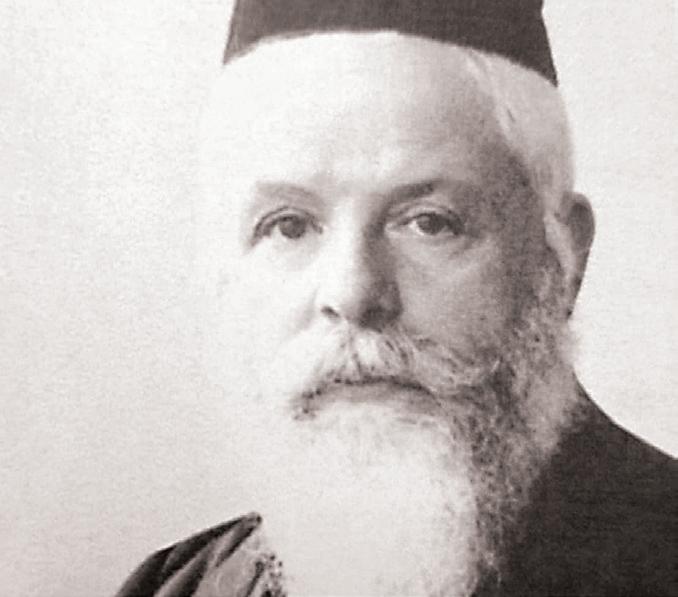

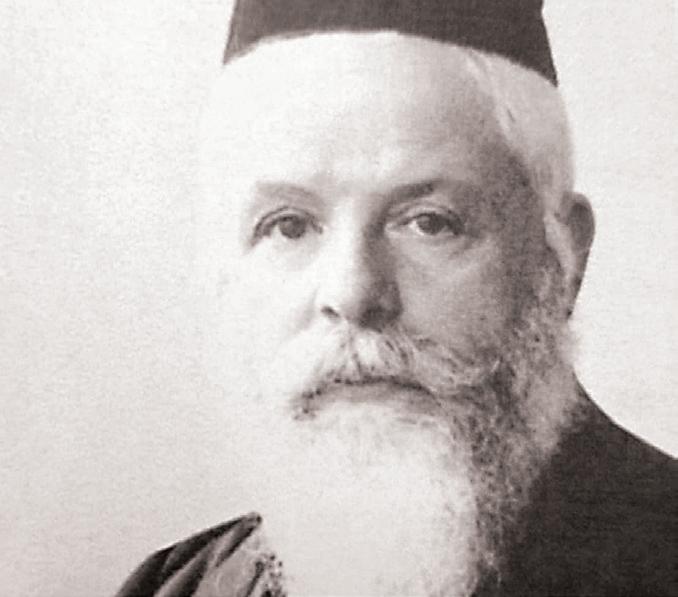

Rabbi Dr. Yitzchak Isaac Halevi Herzog (Lomza, Poland, 1888-Jerusalem, 1959)

By Rabbi Yirmiyohu Kaganoff

By Rabbi Yirmiyohu Kaganoff

Contrary to what many people think, the first chief rabbi of the modern State of Israel was not Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook but Rabbi Yitzchak Isaac Halevi Herzog. Rav Kook was the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of the New Yishuv, but he passed away in 1935, thirteen years before the Declaration of Independence of the State of Israel. After Rav Kook’s passing, the search committee for a new rav placed two candidates before the body in charge of the selection, and Rabbi Herzog, then serving as the chief rabbi of the Irish Free State, was chosen over Rabbi Yaakov Moshe Charlop, the rosh yeshivah of Yeshivat Mercaz HaRav, now located in the Kiryat

Rabbi Yirmiyohu Kaganoff, formerly a pulpit rav in Buffalo and Baltimore, now lives in Neve Yaakov in Jerusalem, where he teaches, writes, and visits Jewish communities all over the world. He is a prolific author on rabbinic scholarship, in both English and Hebrew.

Moshe neighborhood of Yerushalayim.

Rabbi Herzog was born in 1888, in Lomza, Poland, where his family had lived for several generations. His father, Rabbi Yoel Herzog, was a well-known talmid chacham in the city and served as one of the dayanim, alongside the city’s rav, Rabbi Noach Yitzchak Diskin. (He was a brother of Rabbi Yehoshua Leib Diskin, one of the unofficial rabbanim of the Old Yishuv of Yerushalayim and the rebbi of Rabbi Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, first rav of the Eidah Hachareidis.) Rabbi Yoel Herzog also served as a dayan alongside Rabbi Malkiel Tzvi Halevi Tannenbaum, author of Divrei Malkiel, one of the greatest posekim in Lithuania in his generation. In contrast to most rabbanim of the time, Rabbi Yoel Herzog has been described as a “fiery Zionist”—he was a strong supporter of Chovevei Zion, a forerunner of the Zionist movement. As a young man, he met Rabbi Shmuel Mohilever, one of the early founders of Religious Zionism, who invited the much younger Rabbi Yoel Herzog to the first Zionist Congress, where Rabbi Mohilever planned to introduce him to Theodor Herzl. At the last minute, Rav

Yoel was unable to attend because his son Yitzchak became seriously ill. Most fortunate for the history of Klal Yisrael, the young Yitzchak recovered.

The younger Rabbi Herzog grew up in an environment that believed very strongly in the building of a modern Jewish presence in Eretz Yisrael, and later on in his life he had no difficulty cooperating with non-religious elements to bring about the creation of a Jewish state in the Holy Land.