COVER STORY:

Te Great Jewish Awakening

By Rachel Schwartzberg

Is the Orthodox Community Doing Enough?

By Rachel Schwartzberg

Teshuvah A fer October 7

By Rabbi Lawrence Kelemen

One Year Later: How October 7 Changed Me

With the frst anniversary of October 7 approaching, we asked readers to tell us how they were impacted by a day that will live on forever in our hearts and souls.

Supporting At-Risk Youth in Israel Post–October 7

By Aviva Engel

JEWISH SOCIETY

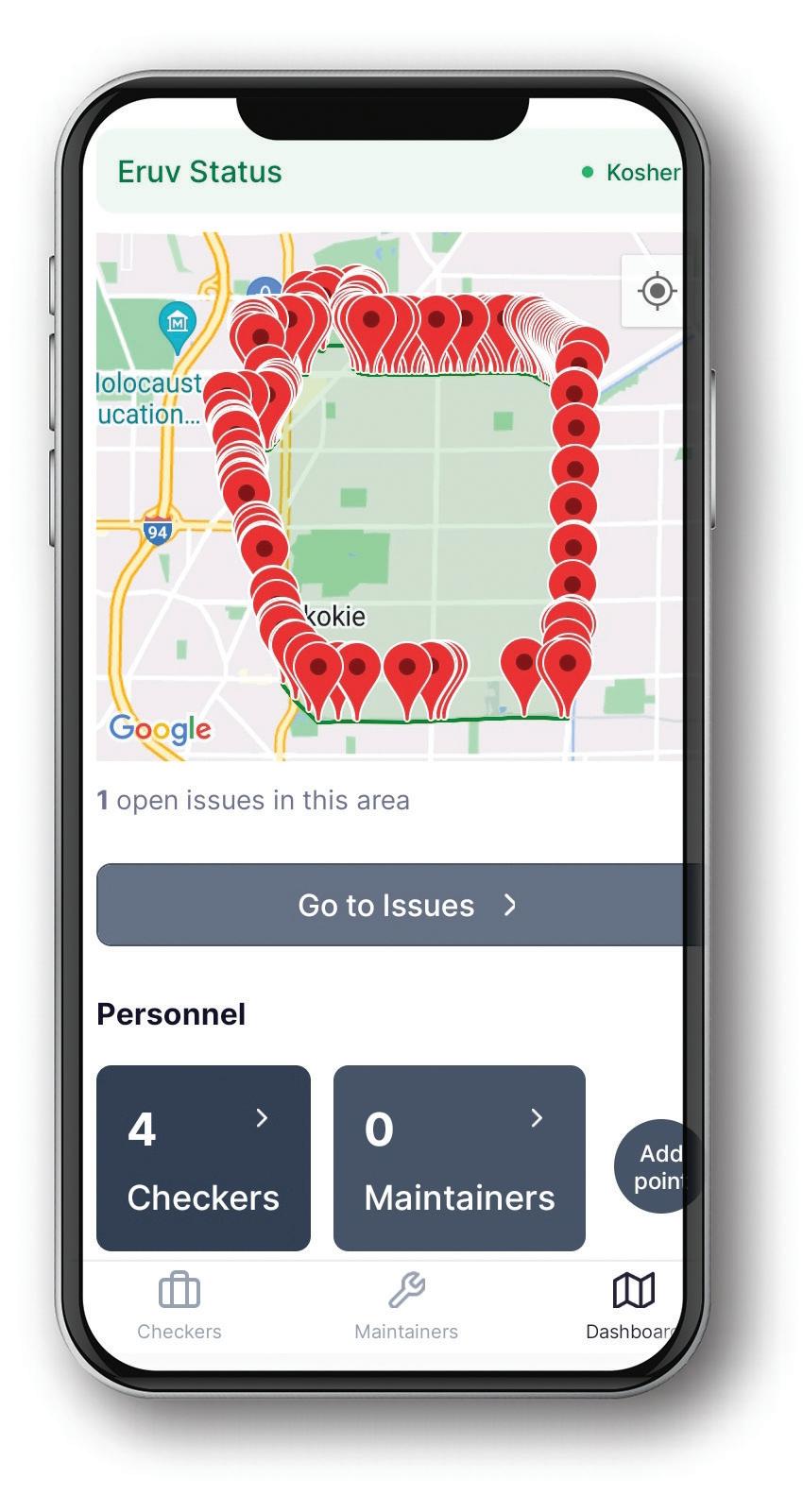

Te Eruv Revolution By Merri Ukraincik

Te Eruv Maven: Meet Rabbi Micah Shotkin

By Steve Lipman

A New Normal?

Pro-Palestinian agitators have found a new venue for their hate-flled protests—our shuls.

By Sandy Eller

PHOTO ESSAY

Te Artistry of the Etrog Box

By David Olivestone

ON MY MIND

Is it Time for a Deep Dive into Feelings?

By Moishe Bane

LETTERS

FROM THE DESK OF RABBI MOSHE HAUER

Lema’an Achai V’Rei’ai: Pursuing Unity

MENTSCH MANAGEMENT

Bring Your Jewish Self to Work

By Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph

IN FOCUS

Four Traits of Successful Social Entrepreneurs

By Tamar Frydman

KOSHERKOPY

Kosher Conundrums

LEGAL-EASE

What’s the Truth about . . . Milchemet Mitzvah?

By Rabbi Dr. Ari Z. Zivotofsky

THE CHEF’S TABLE

Squash Sensations for the Holiday Table

By Naomi Ross

FROM THE PAGES OF OU PRESS

Rosh Hashanah: Let Tere Be Light

BOOKS

Rav Schachter on Pirkei Avos: Insights and Commentary Based on the Shiurim of Rav Hershel Schachter

Adapted by Dr. Allan Weissman Reviewed by Ben Rothke

Masters of the Word: Traditional Jewish Bible Commentary from the Twelfh through Fourteenth Centuries (Vol. 3) By Rabbi Yonatan Kolatch Reviewed by Rabbi Yaakov Taubes

Kaddish Around the World: Uplifing and Inspiring Stories By Rabbi Gedalia Zweig Reviewed by Steve Lipman

REVIEWS IN BRIEF By Rabbi Gil Student

LASTING IMPRESSIONS

Holy Pineapples By Tania Hammer

THE MAGAZINE OF THE ORTHODOX UNION jewishaction.com

Editor in Chief Nechama Carmel carmeln@ou.org

THE MAGAZINE OF THE ORTHODOX UNION jewishaction.com

Associate Editors

Sara Goldberg • Sarah Weiner

RABBIS OF THE IDF

Associate Digital Editor Rachel Eisenberger

Editor in Chief Nechama Carmel carmeln@ou.org

Rabbinic Advisor

Rabbi Yitzchak Breitowitz

Assistant Editor Sara Olson

Book Editor

Rabbi Eliyahu Krakowski

Literary Editor Emeritus Matis Greenblatt

Contributing Editors

Book Editor Rabbi Gil Student

Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein • Moishe Bane • Dr. Judith Bleich

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Goldberg

Rabbi Sol Roth • Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter

Rabbi Berel Wein

Contributing Editors

Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein • Dr. Judith Bleich

Editorial Committee

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman • Rabbi Hillel Goldberg

Moishe Bane • Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin • Deborah Chames Cohen

Rabbi Sol Roth • Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter

Jewish Action’s cover story “Religion on the Battlefeld” (summer 2024) includes excellent articles by some of Israel’s most erudite rabbis. But other than Carol Ungar’s interview with a member of the women’s division of the Casualty Treatment Unit (the chevra kadisha) of the IDF Rabbinate, there are only a few passing references to the rest of the work of the IDF Rabbinate. An interview with its chief rabbi, Brigadier General Rabbi Eyal Krim, or with two former IDF chief rabbis, Brigadier Generals (reserves) Rabbi Yisrael Weiss and Rabbi Raf Peretz, would have enriched this issue. Rabbi Krim oversees everything relating to religion in the IDF and is deeply involved in discussions on ethical issues that arise. Rabbis Weiss and Peretz have been giving chizuk to soldiers, the wounded, bereaved families and to those who are doing the heart-wrenching, holy work in the Casualty Treatment Unit at the Shura base.

Rabbi Berel Wein

Rabbi Binyamin Ehrenkranz • Rabbi Yaakov Glasser

David Olivestone • Gerald M. Schreck • Dr. Rosalyn Sherman

Rebbetzin Dr. Adina Shmidman • Rabbi Gil Student

Editorial Committee

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin • Rabbi Binyamin Ehrenkranz

Rabbi Avrohom Gordimer • David Olivestone

Gerald M. Schreck • Rabbi Gil Student

Copy Editor Hindy Mandel

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Design 14Minds

Intern Shira Kramer

Advertising Sales

Design Andréia Brunstein Schwartz

Joseph Jacobs Advertising • 201.591.1713 arosenfeld@josephjacobs.org

Advertising Sales

Subscriptions 212.613.8140

Joseph Jacobs Advertising • 201.591.1713 arosenfeld@josephjacobs.org

ORTHODOX UNION

Subscriptions 212.613.8134

President Mark (Moishe) Bane

ORTHODOX UNION

In addition to overseeing kashrut, religious items for the soldiers, synagogues, Torah classes and educational activities, the IDF Rabbinate has a Halachah Branch. Among its many published books is Torat Hamachaneh, a halachic volume of teshuvot on army issues, which a source in the IDF Rabbinate says is “the most comprehensive book ever written on these issues.” He also said that their most important work in this war was the identifcation of the deceased, which in some cases was extremely complicated. IDF rabbis also work to keep the morale of soldiers high. Morale on the battlefeld is profoundly intertwined with soldiers’ motivation to fght.

President Mitchel R. Aeder

Chairman of the Board

Howard Tzvi Friedman

Vice Chairman of the Board Mordecai D. Katz

Chairman of the Board Yehuda Neuberger

Vice Chairman of the Board

Barbara Lehmann Siegel

Chairman, Board of Governors Henry I. Rothman

Chairman, Board of Governors Avi Katz

Vice Chairman, Board of Governors Gerald M. Schreck

Vice Chairman, Board of Governors Emanuel Adler

Executive Vice President/Chief Professional Officer Allen I. Fagin

Executive Vice President Rabbi Moshe Hauer

Chief Institutional Advancement Officer Arnold Gerson

Executive Vice President & Chief Operating Officer

It would have also been worthwhile to highlight the Talmudic Encyclopedia’s edition War in the Light of Halachah, released in January 2024. Rabbi Dr. Avraham Steinberg is head of the editorial board of the Talmudic Encyclopedia and this edition is in memory of Col. Yonatan Steinberg (no relation to Rabbi Steinberg), of blessed memory, commander of the Nahal Brigade, who fell in battle on October 7. In addition to Col. Steinberg’s impressive military career, he had studied at Horev Yeshiva High School in Jerusalem and in the Ma’ale Eliyahu Yeshiva in Tel Aviv. He lived in the deeply religious community of Shomria in the Negev. Te edition, in addition to specifcally war-related issues, includes topics such as ahavat Yisrael and machloket, topics important to Am Yisrael today.

Senior Managing Director Rabbi Steven Weil

Rabbi Josh Joseph, Ed.D.

Chief of Staff Yoni Cohen

Executive Vice President, Emeritus

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Managing Director, Communal Engagement Rabbi Yaakov Glasser

Chief Financial Officer/Chief Administrative Officer Shlomo Schwartz

Chief Human Resources Officer Josh Gottesman

Chief Human Resources Officer

Rabbi Lenny Bessler

Chief Information Officer Miriam Greenman

Chief Information Officer Samuel Davidovics

Managing Director, Public Affairs Maury Litwack

Chief Innovation Officer

Rabbi Dave Felsenthal

Chief Financial Officer/Chief Administrative Officer Shlomo Schwartz

General Counsel

Director of Marketing and Communications Gary Magder

Rachel Sims, Esq.

Jewish Action Committee

Executive Vice President, Emeritus

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Gerald M. Schreck, Chairman Joel M. Schreiber, Chairman Emeritus

Jewish Action Committee

Dr. Rosalyn Sherman, Chair

Gerald M. Schreck, Co-Chair

Te rabbis of the IDF Rabbinate, and Col. Steinberg, in his life and in his heroic death, are the kind of people to be emulated by the readers of Jewish Action.

Toby Klein Greenwald

Efrat,

Israel

FEEDBACK FROM A MILUIMA

©Copyright 2018 by the Orthodox Union Eleven Broadway, New York, NY 10004 Telephone 212.563.4000 • www.ou.org

Joel M. Schreiber, Chairman Emeritus

©Copyright 2024 by the Orthodox Union

40 Rector Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10006

Twitter: @Jewish_Action Facebook: JewishAction

Telephone 212.563.4000 • www.ou.org

Facebook: Jewish Action Magazine

Twitter: Jewish_Action Linkedln: Jewish Action Instagram: jewishaction_magazine

In the article about miluim wives (“A New Kind of Battlefeld” [summer 2024]), I was, unfortunately, misrepresented. While my husband was serving in the IDF, my family was not in fnancial distress. In fact, because we received so much support, fnancially we were better of. Almost all of our meals were delivered by various organizations. My children received extra food at school since their father was in miluim. One shul even arranged for us to have free babysitting so I could take my older children to various activities. As difcult as it was, there were times I felt I was being hugged by members of the community.

Yes, being a “miluima” [a woman with children whose husband has gone to war] was tough and lonely. My parents could not come help because of health reasons and I have no family in Israel. I ofen felt alone. But I am proud to help the war efort.

Sarah Weller Jerusalem, Israel

While reading your feature “Modesty in the Modern Age” (summer 2024), two thoughts came to mind.

Tough you do mention social media, I didn’t see any references to the ubiquitous cell phone. It has unfortunately become commonplace for many people to whip out their phones at any time and place. One of my pet peeves is being forced to listen in on random and ofen inane conversations in elevators, and on public transportation, in restaurants or behind someone on line at the cashier. Private conversations in public areas merited mention.

Secondly, for a long time before releasing my book Unmatched: An Orthodox Jewish woman’s mystifying journey to fnd marriage and meaning, I had to decide whether I’d aim for publicity or privacy. Would I show my face, do a book tour or do video podcasts? On the one hand, nothing beats the human connection between author and reader to make sales happen. On the other hand, I had to consider what the publicity would do to all the characters in my book, including myself.

When I considered the people I admired, I realized that they were infuential in my life without being any kind of star infuencer. Tey were modest and humble. Tey didn’t brand themselves or need social media, and those that did use it always pushed their message more than themselves. From the emotional letters I’ve received afer the book came out, I think I can say that I did indeed make the right choice.

Sarah Lavane (pen name)

RECOGNIZING YOUR VALUE

In “What Are You Good At? Te Art of Positive Feedback” (summer 2024), Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph helps the reader fnd ways to discover the good in themselves. “Feedback” and “positivity” are not mutually exclusive. A manager can point out what needs improvement while also praising the employee. We, too, should see our own strengths, rather than fall down the rabbit hole of “weaknesses.” Build on your own accomplishments to grow and succeed.

Te Ohr HaChaim Hakadosh, on the very famous story of Yaakov blessing Ephraim and Menashe that Rabbi Joseph cites, questions why Yaakov asked “who are these?” Of course Yaakov knew who his grandsons were, but by elaborating on Yosef’s fne children, Yosef would allow the berachos to be fulflled. Another peshat from the Ohr HaChaim is that Yaakov wanted to know what Ephraim and Menashe did in their own right to earn the blessings. In other words, he was asking, who are you? What have

Jewish Action won six Simon Rockower Awards for Excellence in Jewish Journalism for work that appeared in 2023. The prestigious awards, referred to as the “Jewish Pulitzers,” are sponsored by the AJPA, which holds a journalism competition for leading Jewish magazines and newspapers across the country. The entries are judged by a panel of judges with expertise in journalism, writing/reporting, editing, graphic design and cartooning in both Jewish and nonJewish media. Winning articles included:

First Place

l Steve Lipman, “Good Deeds Make Good Neighbors” (fall 2023)

Second Place

l Merri Ukraincik, “Navigating Widowhood” (spring 2023)

l Channah Cohen, Batsheva Moskowitz, “Singlehood in the Community: Are We Missing the Mark?” (fall 2023)

l Nechama Carmel, “Up Close with Rivka Ravitz” (winter 2023)

Honorable Mention

l Rabbi Netanel Wiederblank, “What Artificial Intelligence Teaches Us about What It Means to Be Human” (spring 2023)

l Toby Klein Greenwald, Tania Hammer, Batsheva Moskowitz, Merri Ukraincik, Carol Ungar, “The Unity of a Nation” (winter 2023)

Transliterations in the magazine are based on Sephardic pronunciation, unless an author is known to use Ashkenazic pronunciation. Tus, the inconsistencies in transliterations in the magazine are due to authors’ or interviewees' preferences.

Tis magazine contains divrei Torah and should therefore be disposed of respectfully by either double-wrapping prior to disposal or placing in a recycling bin.

you accomplished? What goals are you working on to be successful in life? One might recognize a face or a name as being from a prominent Jewish family, but what is that individual doing in their own right?

Trough positive feedback, we allow blessings to enter the world.

Howard Jay Meyer Brooklyn, New York

David Olivestone’s touching article “Mah Shlomcha?” (summer 2024) describes reciting Kaddish for a soldier who has no family member to do so. Mr. Olivestone writes:

A while ago, I noticed that a friend had begun to say Kaddish following Aleinu at each tefllah. He put me in touch with an organization that works to ensure that every chayal killed in action has someone to say Kaddish for him if there is no family member to do so. So now I, too, am saying Kaddish for a twenty-year-old soldier who fell in Gaza.

Afer my parents died, I realized that in death they bestowed upon me a gif to share with other Jews: to say Kaddish for those without family. Like Mr. Olivestone, I too would like to say Kaddish for soldiers and would appreciate learning more about the organization mentioned in the article. Tis is a meaningful way for me to contribute to Israel and its soldiers from afar.

Joshua Annenberg Teaneck, New Jersey

David Olivestone Responds:

As I wrote to Mr. Annenberg personally, the organization is called Chesed Chaim V’Emet (holy.hhe.org.il/en/kaddishlkol-kadosh/). Te eleven months of saying Kaddish for the victims of October 7 have now passed, but hardly a day goes by now when we do not learn the names of soldiers who have died in battle. Te families of the many chayalim and civilians who have fallen, whose parents or other close relatives are, for whatever reason, unable to say Kaddish regularly, greatly value the comfort this organization brings them. For those of us saying Kaddish on their behalf, it’s a tangible, thrice-daily reminder of their sacrifce on our behalf. Anyone who wishes to participate can fll out a form on the website or email them at kadish.lechol.kadosh@ gmail.com, and you will be contacted. May we hear only besorot tovot in the future.

To send a letter to Jewish Action, e-mail ja@ou.org. Letters may be edited for clarity.

By Rabbi Moshe Hauer

ARabbi

Moshe Hauer is executive vice president of the Orthodox Union.

When we are so internally rancorous, we can hardly complain about the antisemitism that surrounds us.

JOIN US FOR AN OPEN HOUSE AT LANDER COLLEGE FOR WOMEN SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 3, 2024 • 1:00-4:00pm • 227 W. 60th St., New York

At Touro University’s Lander College for Women, you’ll find academic excellence, a commitment to Torah values, and supportive faculty dedicated to helping you reach your goals. Whether it’s a pathway program to one of Touro’s professional schools, admission to prestigious graduate schools, an internship at a top firm or a job at a Fortune 500 company, TOURO TAKES YOU THERE.

Marian Stoltz Loike, Ph.D., Dean

sinat chinam, sinat chinam

connection between Jews must be a guiding principle, not just an emotion.

mesorah

Our mentor for navigating the imperfect world of galut is Rav Yochanan ben Zakkai. As the Talmud12 records, his guiding principle was a version of tafasta merubah lo tafasta, the realization that one who seeks everything will often end up with nothing. Rav Yochanan ben Zakkai was humbly pragmatic and understood that we must reconcile with our current state of imperfection, with reality and with others, and take what we can get. This attitude allowed him the clarity to salvage both the Torah and the remnants of the Davidic dynasty

even as Yerushalayim and the Beit Hamikdash were being destroyed. It also made him the leader who would continue the teaching of Torah into that post-Destruction period during which the Jewish people would necessarily be less priorities,13 who led the Jewish people according to those

That is the critical adjustment we can make. Our characteristic drive to prevail must move us to build and promote our vision with the zeal and idealism that will enable others, while recognizing and peaceably accepting that others will be doing the same to advance their own visions. Our

success as prevailing in shutting down the ways of others.

Ha’emet v’hashalom ehavu. Love both truth and peace. must distinguish ourselves as passionately committed Jews who prioritize both our halachic and principles and our absolute and unconditional desire for connection to each and every other Jew. That combination will allow Klal Yisrael to prevail.

Postscript:

Trips

with each other, we have been profoundly inspired by for each other.

commitment to the well-being of every Jew.

It has often been noted that every soldier of Tzahal, by virtue of their dedication to give their lives for the Jewish people, shares the distinction of the who are in a class of their own in the World to Come.14 That is the world designated for Klal Yisrael, the world of “

” In that world, those whose dedication extends clearly to all the Jewish people occupy the highest place. They are the Jews of , of Klal . Let us learn from them to dedicate all our energies to each other and not with each other.

56b. Note that the Talmud expresses reservations about Rav Yochanan ben Zakkai’s negotiating strategy, but recognizes that it was Divinely inspired. Ultimately, he not only led Klal Yisrael through the days of Destruction but was recognized as Hillel’s successor, and his guidance defned how we live as a people following the Churban 13. Avot 2:8–9. 14. Bava Batra 10b.

Thoughtful, compassionate, mission-driven. Yeshiva University students embody these values, creating a profound impact both at home and across the globe. Whether mentoring schoolchildren in NYC, visiting with or delivering food to the elderly or helping to rebuild Israeli communities afected by Oct. 7, they are unwavering in their commitment to improving lives—one act of kindness at a time.

IT’S YOUR TIME TO RISE AT YESHIVA UNIVERSITY

By Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph

It’s no surprise that in a post–October 7 world, Jews worldwide are exploring, considering, rediscovering and reconnecting to their roots. A quick Google search yields headlines such as the following:

l “Jewish identity afer October 7”

l “ Tese US Jews are recalibrating their identity in a tempestuous post-Oct. 7 environment”

l “Young Jews worldwide feel new sense of identity afer October 7”

l “October 7 changed my Relationship with Judaism”

l “Embracing my Jewish roots afer Oct. 7 has meant subjecting myself to antisemitism”

l “Afer the shock of October 7, young Jews reconnect with their religion”

How is this manifesting in our communities and networks as well as in the workplace?

Within the OU, the number of public school teens who have reached out to set up a JSU (Jewish Student Union) club through NCSY, the expansion of JLIC (Jewish Learning Initiative on Campus) programs on campuses, and the increase in Israel Free Spirit Birthright trip registrants (including newly established volunteer trips in the afermath of October 7) suggest the transformation of the landscape and the burgeoning opportunity taking place before our eyes.

I remember my high school teacher, Mr. Levy, a shaliach from Israel, asking us if we considered ourselves a Canadian Jew or a Jewish Canadian? Which one is the descriptor, and which one is the essence? Mr. Levy was surprised to hear most of my fellow students answering that they saw themselves frst as a Canadian. And what perhaps he might have better appreciated today was that they considered Jewishness to be part of their identity at all.

Is being Jewish a part of your identity? If you name fve characteristics that are key to who you are—is “Jewish” one of them? Is it an adjective or a noun? Is it the sum total of who you are in everything you do?

In his bestseller Bring Your Whole Self to Work, Mike Robbins draws on this idea, explaining that we can work better, lead better and be more engaged and fulflled if—instead of trying to hide who we are—we show up fully and authentically.

For us to thrive professionally, especially in today’s world, we must be willing to bring our whole selves to the work that we do. And for the groups, teams and organizations that we’re a part of to truly succeed, it’s essential to create an environment where people feel safe to bring all of who they are to work.

But what does this mean? Maybe those privileged to work at the OU and in other frum workplaces can share in each other’s semachot, discuss Shabbat plans and play Jewish geography. But this isn’t a reality for all, and even in Jewish communal workplaces it’s important to keep a separation between our personal and professional lives.

vice president/chief operating ofcer

Te theme of this column is that you can be a Jew and a professional, a mentsch and a manager at the same time. Tey align well—but is there one that takes priority? When faced with a situation in the workplace, does “mentsch” defne your management? Will you think frst of the values and faith that inform your conduct?

In his article “What Does It Mean to Bring Your ‘Whole Self’ to Work?,” content and marketing professional Ash Read writes: “Wholeness means we bring all the elements of who we are to work—our passions and strengths, our side projects and relationships, our partners and kids.” But, warns brand strategist Susan LaMotte, “ Te reality of whole self policies is ofen that companies expect people to bring their whole selves to the workplace because they’re not giving them reasonable time to live a whole life outside of it.”

So we are lef wondering: How much of our Jewish selves should we bring to work?

Perhaps that depends on how much your Jewishness is part of who you are.

Donate

So we are left wondering: How much of our Jewish selves should we bring to work?

As we enter our most introspective time of year, and as we approach the one-year anniversary of October 7, we have an opportunity to contemplate how we will bring our whole Jewish, mentschlich selves to work in the coming year. We should consider whether we can bring pieces of our Jewish selves with us to work. We should refect on whether our Jewishness defnes us enough so that we bring that identity to work. We should contemplate whether our Jewishness afects how we interact at work, such as when and how we speak to a colleague or a boss.

Te Forbes Coaches Council ofers thirteen strategies to bring your whole self to work—which we could examine through a Jewish lens. In fact, the last two suggestions might be at the top of our list at this time of year, and perhaps all year round. Te frst is to do some “self-searching,” ensuring that whatever resonates with you at the deepest level is what guides you in your work. Te second strategy is to become aware of potential blind spots, and to use your own self-management, core values and unique style of leadership to drive you every day.

“Bringing your ‘whole self’ to work doesn’t mean using the excuse ‘that’s just the way I am.’ Being ‘authentic’ is not an excuse for behaving badly.”

We in the Orthodox Jewish community have a level of responsibility here. Are we doing enough to help our less-connected Jewish brothers and sisters at work? To be their whole selves? In a world of rising antisemitism and increased Jewish awakening, have we soul-searched enough to understand where our own Jewishness lies in the panoply of our self-defnitions?

What does it mean to be an Orthodox Jew in your workplace?

By Rachel Schwartzberg

Afer her bat mitzvah, Gracie Greenberg, who recently concluded her freshman year at Pace University, fgured she’d had enough of Judaism.

“My feeling was: I’m done! No more Judaism for me,” recalls the Long Island, New York, native.

But about a month into her frst semester studying musical theater, everything changed.

“October 7 was a real wake-up call,” she says, recalling her horror at the brazen attack in Israel and the rise in antisemitism that followed—particularly on college campuses like hers. “Being Jewish was part of my identity I hadn’t given much thought to. Why was everyone targeting me?”

As Greenberg was struggling to make sense of the hatred that suddenly surrounded her, she heard about a free dinner at Meor, a national outreach organization with a branch at nearby New York University (NYU). What she found there was overwhelming.

“I discovered a strong community of Jews that included all types,” she says—which she’d never experienced before. Tat dinner set her on a journey to explore Judaism more deeply.

Greenberg never expected that she would travel with Meor to both Poland and Israel in her freshman year of college, but those trips helped her clarify who she is and what’s important to her. It’s been transformative, she says, to discover the role of spirituality and the value of personal responsibility in Judaism.

“I decided I want to marry Jewish,” she says. “I’ve started talking to G-d once a day, and I’ve been taking on small mitzvot. I’ve learned that it’s what I’m doing for Hashem that really matters.”

While Jews the world over have been experiencing a reawakening, this particular article is focused on American Jewry.

October 7 shocked the Jewish world, and the outpouring of anti-Israel and anti-Jewish rhetoric that followed—both on social media and in real life—has sparked a religious awakening among Jews across the US. As counterintuitive as it may seem, the most common Jewish reaction to rising antisemitism has not been laying low and hiding one’s identity, but rather an increase in Torah learning and mitzvah observance and a stronger connection to the Jewish community.

In fact, a recent survey of American Jews by the Jewish Federations of North America noted the “explosion in Jewish belonging and participation,” referring to it as “ Te Surge.” According to the survey, “Of the 83 percent of Jews who were ‘only somewhat,’ ‘not very’ or ‘not at all engaged’ prior to October 7, a whopping 40 percent are now showing up in larger numbers in Jewish life. Tis group—equal to 30 percent of all Jewish adults and nearly double the

proportion of Jews who identify as ‘deeply engaged’—represents the greatest opportunity for broadening and deepening Jewish life” (https:// ejewishphilanthropy.com/what-youneed-to-know-about-the-surge-ofinterest-in-jewish-life/).

Jewish education is benefting as well: 39 percent of Jewish parents indicated they may reevaluate or reconsider educational or summer programs for their children, and 38 percent of parents with kids in a secular private school are considering making the move to Jewish day schools. Among Jews who are not members of synagogues—which according to Pew estimates is 64 percent of US Jews—37 percent say they’d be open to joining one now.

“October 7 lit a fre for Jews around the world,” says Rabbi Mark Wildes, founder of the Manhattan Jewish Experience (MJE). “We’re seeing this real need to learn more about Judaism to make sense of it.”

While Rabbi Wildes has seen a bump in attendance at MJE programs since October 7—MJE’s mission is to engage less afliated Jews in their twenties and thirties in New York—he believes it’s not the numbers that are noteworthy but the eagerness of the participants.

“It’s not hundreds of people coming,” he says. “But there’s a certain urgency among those who are coming. Tey have a need to support Israel, when they previously had, at most, a tenuous connection.”

Rising antisemitism, he says, has “exposed a raw nerve among assimilated American Jews. Tey are suddenly asking, ‘What do I believe in that’s worth defending?’”

American Jews are reaching out—because what they’re actually looking for is “authenticity and connection.” Courtesy of Aish.com

Tis sentiment is echoed across college campuses, as previously unengaged Jewish students struggle to cope with hostility and even outright violence from

Rachel Schwartzberg is a writer and editor who lives with her family in Memphis, Tennessee.

Since October 7, he says, “we went from ‘why be Jewish?’ to ‘how to be Jewish.’”

Courtesy of Aish.com

to be shomer Shabbos,” says Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, co-director, along with his wife Sharona, of OU-JLIC at University of California-LA (UCLA).

“We’re seeing young men who are deciding to wear a kippah for the frst time on campus.”

pro-Palestinian encampments—and schools unwilling to take a stand to protect their Jewish students. Like Greenberg, Jewish students have been targeted and marginalized, and they feel entirely unequipped to respond to anti-Jewish and anti-Israel accusations.

“Every two or three weeks I meet a student who tells me he’s trying

Te primary mission of OUJLIC is to support Orthodox day school graduates on secular college campuses. “We’re not here to reach out to unafliated Jews,” says Rabbi Kaplan. “But we’re seeing so many students who might have been loosely connected before—people who were on the outskirts of the Orthodox community—who are interested in more.”

Perfectly balanced.

“Someone said to me the other day, ‘ Tere’s got to be more to Judaism than bagels and lox if they hate us so much,’” says Rabbi Aaron Eisemann, director of Meor at NYU. “ Tese students want to understand what Judaism is really about.”

While he and his team used to spend signifcant time recruiting kids for programs, those eforts are no longer necessary. “Te encampments recruit them for us,” notes Rabbi Eisemann, who has been working in campus outreach for nearly twenty years. Not only are more kids showing up, but there has been a signifcant growth in the level of content he and his staf are sharing.

“ Tat’s really more telling,” he says. “In the past, the average liberal arts college student questioned the need for Judaism at all; we spent a lot of time on basics. But the campus protests have answered that question for them. Te level of learning we’re doing now is so much higher.”

“October 7 lit a fre for Jews around the world,” says Rabbi Mark Wildes (right), founder of the Manhattan Jewish Experience (MJE). “We’re seeing this real need to learn more about Judaism to make sense of it.” Courtesy of MJE

I’ve been working in the Jewish community for thirty years. I’ve never seen anything like this.

“ Tere’s no way we could ever have gotten Jews to wake up like this,” says Steve Eisenberg, a

successful investment banker turned outreach activist. “It took 1,200 murdered Jews to do this; if we had a billion-dollar budget for outreach, we could not have done this.

“Jews who never did Seders, did Seders this year. Jews who never did Shabbat are trying Shabbat,” says Eisenberg, who serves as the director and co-founder of Jewish International Connection (JIC), a program that “enhances Jewish connection around the world through events and helps strengthen Jewish identity.” “I can’t tell you that the changes are dramatic, but it’s made a large percentage of the Jewish population in America feel more Jewish and identify as Jews. It

cuts deep within the soul of the Jewish people in America.”

“I heard of three Jewish twenty-yearolds who broke up with non-Jewish girlfriends,” he says. “Why? Because, all of a sudden, their non-Jewish girlfriends were siding with Hamas. Te men thought: you are really siding with people who raped and pillaged and murdered babies and burned them alive? Who are you? Another guy told me three people in his family have decided to marry Jews now. Tese are Jews who before October 7 couldn’t care less about intermarrying.”

Since October 7, he says, “we went from ‘why be Jewish?’ to ‘how to be Jewish.’ ”

For your typical unafliated college student, “a rabbi was completely unrelatable,” says Rabbi Eisemann. Tat was before October 7. “But when you can’t go to class because people are yelling at you, the same rabbi is now a safe haven.” Rabbi Eisemann posits that right now young people, especially, are ready for authentic Torah learning because barriers have fallen away.

Grant Ghaemi is a perfect example. A senior at NYU last fall, he found himself very upset afer October 7. “I was disgusted, and I confronted people about their [social media] postings . . . and I lost friends over it,” he recalls. His own reaction surprised him. “ Tere was clearly something about what happened on October 7 that changed me,” he says. Before, he had prided himself on not letting political views get in the way of relationships.

A few weeks later, he met Rabbi Eisemann in front of the NYU library. “With a big smile,” says Ghaemi, “he stretched out his hand and asked, ‘Are you a Jew?’ Up until then, when someone asked me that, I’d say no or keep walking. But this time I thought to myself, if there’s ever a time to

embrace this, the time is now. So I shook his hand and said, ‘Yes I am.’”

Ghaemi grew up in a “very secular household” in New Jersey; his father was raised in a Muslim family in Tehran. “As a kid, my family celebrated Chanukah, a version of Rosh Hashanah, and Yom Kippur when my mother remembered,” he says. “And also Christmas and Easter and Eid.”

In his last semester at NYU, Ghaemi committed to learning at Meor at least once a week, and he attended his frst Shabbaton in Passaic, New Jersey.

He admits he “felt terribly out of place” at frst when he arrived at his hosts’ home. “I had preconceptions about Orthodox Jews,” he says. “I didn’t know any Hebrew. I didn’t even know what Shabbat was.” However, he was quickly blown away by the warm welcome he received—“from literal strangers.”

“I was shocked to fnd an entire community that viewed me as part of their extended family,” he says. Ghaemi ended up becoming a regular on Shabbatons, and even brought his mom along to get a taste of Shabbat, too. Afer graduating in the spring, he began working remotely so he could participate in a six-week Meor fellowship in Lakewood, New Jersey.

Tis “reawakening” spans all demographics and geography.

Rabbi Josh Broide, director of the Center for Jewish Engagement (CJE), a division of the Jewish Federation of South Palm Beach County, and outreach rabbi at Boca Raton Synagogue in Florida, says he ran an Israel-oriented program soon afer October 7 and expected a dozen people. More than 100 showed up. Even months afer October 7, program attendance remains signifcantly higher than in the past. “Of course you’d get people [at previous programs], but nothing in the numbers like this,” he says. “And the people who would show up were the people you’d expect to show up. But now we are getting people we would never expect to show up.”

Moreover, since the Hamas attack, afer any Israel-centered talk or presentation, he has come to expect a long line of people waiting to speak to him. “Tey say things like, ‘Rabbi, I’m so happy to be here. What else can I do to get involved?’

‘Rabbi, Israel is the most important thing on my

In the days and weeks immediately following October 7, there was a marked increase in participation in both the Community Kollel of Greater Las Vegas’s outreach programs and its regular minyanim and shiurim. Courtesy of Rabbi Nachum Meth

mind.’ I’ve been working in the Jewish community for thirty years. I’ve never seen anything like this.”

Tis scenario is playing out all over the outreach world. “We’ve had triple the number of people engaging with us,” says Rabbi Tzvi Broker, one of the humans behind the Live chat feature on Aish.com. For about ten hours a day, six days a week, he or a member of his team mans the chat. Since October 7, the platform has seen more than 5,000 people reaching out each month.

Loren (not her real name) is intermarried and living in New Hampshire, and she recently reached out via the live chat. “Decades afer my attempt to raise my three children Jewish, I am fnally taking the time to focus on my faith,” she wrote. “I’m blown away by the utter courage, strength and historical greatness of the State of Israel and the Jewish people. October 7, for some strange reason, was shocking and paralyzing for me. Since then I have joined the nearby Chabad and latched on to a few more resources for learning.”

Rabbi Broker had a lengthy online conversation with her about how to actualize her newfound

High school senior Noah Simon (frst on the right) has found a supportive community in the JSU club at his public school in Plano, Texas. Following October 7, Noah began wearing tzitzit and a kippah to his public school every day. Seen here, Noah at the JSU Presidents Conference this past November.

passion. She hopes to visit Israel soon.

“A few things have become clear over the past several months,” says Rabbi Broker. “Every Jewish heart was torn on October 7. And the fact that the non-Jewish response didn’t validate that feeling at all made people feel very, very alone. All of a sudden, they felt out of place in their own lives. Tey needed to talk to us.”

He adds that if people just wanted to know more about Judaism, they could fnd ample information online. But Jewish people are reaching out— because what they’re actually looking for is “authenticity and connection.”

“ Tere are Jews in Jewish communities right now who are hungry. Tey want to connect,” says Rabbi Broide.

For teens who are looking to connect with Jewish peers, NCSY runs JSU clubs in public and private (nonJewish) high schools across the US and Canada. JSU has also seen a huge uptick in the number of teens reaching out to open clubs at their schools this year, says Devora Simon, national director of JSU.

“In the past, we received about one online request per month to start a JSU club,” she says. “ Tis year alone we received 120 requests—ninety of them have resulted in the creation of

active clubs. Along with the requests, she says, “about 98 percent of the time, the teens write some version of, ‘Since October 7, I’ve experienced antisemitism and I want to learn more about my heritage.’ Or, ‘I want to come closer to the Jewish community.’”

JSU reached approximately 18,500 Jewish teens last year, 4,000 more teens than the previous year. And not only did more teens show up, Simon adds, but “teens are more engaged than ever, with average attendance per club higher than ever.”

Simon recognizes that the increase in numbers may refect teens’ interest in connecting with other Jews, but she feels that the sense of belonging is a signifcant factor. “Community has always drawn people,” she says. “ Te social aspect is especially critical.”

At the same time, she notes that JSU programs across the country saw a 20 percent increase in the number of teens attending programs outside of school. “We call these ‘higher-level programs.’ Tey are more content and educational oriented,” she explains. For example, a steady group of teens in Baltimore attend a weekly Mesillat Yesharim chaburah at 7 am, waking up early to make the class before heading to their nearby public high school. “ Tat’s a serious commitment,” she notes.

One teen who fnds a supportive community in JSU is Noah Simon. With about ffy Jewish students out of 1,500 in his public school in Plano, Texas, a suburb of Dallas, Noah enjoys the sense of community JSU provides. Meeting during lunch period every other week, the JSU club in his school provides him with “a Jewish environment” and a place where he “can talk with like-minded people and make friends.”

Since October 7, Noah has been wearing tzitzit and a kippah to school. Te senior, who serves as co-president of the JSU at his school, was growing religiously even before the Hamas attack. But October 7 empowered Noah, a sof-spoken sensitive young man, even more, and he began keeping kosher. “I started to not go out for lunch with friends,” he says. “I have defnitely grown a lot.”

Following October 7, this “awakening” was evident among Orthodox Jews as well. While less afliated Jews may have been connecting with the Jewish community for the frst time, Orthodox Jews were pouring into shuls, tefllah gatherings, Tehillim groups and other programs across the country.

“October 7 was traumatic for all of us,” says Rabbi Nachum Meth, executive director and rosh kollel at the Community Kollel of Greater Las Vegas, which serves as a hub for dynamic programs for Jews of all ages, backgrounds and levels of observance. “People felt motivated to go somewhere and do something.” As a result, there was a marked increase in participation in both the Kollel’s outreach programs and its regular minyanim and shiurim. “ Tere were defnitely more frum people coming to shul on Shabbos,” he says. “However, as the acuteness of the situation waned, participation dropped back to normal. Tat’s simply human nature.”

Te big question on the minds of outreach professionals and informal educators is whether the post–October 7 religious awakening will have staying power or not. And it might be too soon to know.

Rabbi Kaplan is hopeful that “people who have made real changes in their lives will stick with them.” However, he points out that sometimes, though signs of outward growth may not all be sustained, people’s experiences now can still have a long-term efect. “For example, maybe these students will make a commitment to send their kids to Jewish schools when the time comes,” he notes.

Overall, however, he believes that this moment in time will have a deep and lasting impact on the Jewish community. “People who are taking on more religious observance have been welcomed with open arms,” he says. “ Tat experience will stick with them for life.”

Although Ghaemi doesn’t know where his journey will take him now that he has graduated college and is working full-time, “the amount I’ve learned about my values and grown as a person has been remarkable,” he says. “Judaism has taught me to seek to be better every day and has given me concrete ways to do that. Until I met Orthodox Jews, I had never known the concept of devotion and sacrifce for higher ideals. I’ve seen the beauty of Shabbos, and families coming together to connect. I want to take that into my life.”

“I can’t say what the future will hold,” says college student Gracie Greenberg, in terms of her religious observance. “Right now, I’m lighting Shabbos candles and saying Kiddush. I would like to continue doing those things, and I plan to keep learning and growing.”

For Jews like Ghaemi and Greenberg, there’s no going back to their pre–October 7 selves.

Courtesy of Aish.com

At Yeshiva University, our rich tradition of over 100 years of Torah study shapes and cultivates generations of future leaders. Our unparalleled Torah learning experience elevates and empowers students through inspiring shiurim and thoughtful programming led by world-renowned rebbeim in a warm and supportive environment. Surrounded by those who share their values, our students learn and grow to become the person they aspire to be—intellectually, religiously, and spiritually.

IT’S YOUR TIME TO RISE AT YESHIVA UNIVERSITY

In the feld of Jewish outreach, there hasn’t been a receptive environment like this since the Six-Day War.

Tat’s a refrain heard among outreach professionals.

“October 7 awakened the sleeping giant,” says Rabbi Aaron Eisemann, director of Meor at NYU.

“It’s an amazing opportunity, and we have to be there for our fellow Jews.”

Kiruv professionals—working with all demographics—stress that they cannot single-handedly reach the many unafliated Jews across the country who are searching for connection in the post–October 7 world. It’s time for all hands on deck.

“To come closer to Torah, people need real relationships—and these all take a tremendous amount of time,” says Rabbi Eisemann. “Rabbis on campuses are desperate for help. Call your local campus rabbi and ofer to host or mentor a student,” he suggests. Frum professionals and entrepreneurs, especially, can play an important role acting as mentors for college students who are focused on launching their careers.

By Rachel Schwartzberg

“Kiruv happens one neshamah at a time,” says Rabbi Zev Kahn, director of Jewish Education Team (JET) based in Chicago. “A person can, on average, have relationships with about eighty people at one time. When you have 5,000 students on a campus, for example, even if 4,500 of them are not interested, one person can’t have a relationship with the 500 who are interested.”

Te bottom line: Outreach cannot be limited to the professionals.

Tis doesn’t mean, says Rabbi Josh Broide, director of the Center for Jewish Engagement (CJE), a division of the Jewish Federation of South Palm Beach County, and outreach rabbi at Boca Raton Synagogue in Florida, that you, as a frum Jew, need to get training as an outreach professional. What it does mean, however, is that you need to pay attention to the opportunities sent your way. “You need to say to yourself: ‘Hakadosh Baruch Hu sent this one person that I just happened to interact with, and I’m going to take responsibility for that person.”’

“I once got a call from someone who lived in a Chicago suburb about an hour and a half away from where

I live,” says Rabbi Kahn. “He said, ‘Rabbi, there’s a guy who works in a cubicle next to me. He’s Jewish and he’s really interested in learning. Would you be willing to drive up and come and learn with him?’ I said to him, ‘You know what? I have a much better idea. Why don’t you learn with him?’ He replied: ‘What, me?! How can I learn with this guy?’”

Many Orthodox Jews are afraid of engaging with Jews who are beginning their religious journeys, says Rabbi Kahn. Tey are worried: What if a beginner asks a question they can’t answer? Rabbi Kahn’s response: “You don’t need to have all the answers. You need to have ahavas Yisrael.”

“If we really believed in what we’re doing and the life we’re living, we’d want to share that with every Jew,” says Steve Eisenberg, co-founder of Jewish International Connection (JIC).

“Jews in the US are much more connected Jewishly today than they were on October 6,” he says. It’s a perfect opportunity for frum people to invite fellow Jews to their Shabbos meals or to their sukkahs, for example. “If every observant Jew would invite one

Jew a month,” he says, “you could have between 15,000 and 20,000 Jews each month experiencing a Shabbos meal.”

But Eisenberg is not optimistic about the majority of the Orthodox community stepping up to the plate. “Where is the Orthodox community?” he asks.

Unfortunately, he says, some in the Orthodox community prefer to focus inward. “We say to ourselves, ‘It’s enough that my kids go to yeshivah and I’m keeping the Torah . . . Hashem will take care of me.’ But we’re not taking achrayus for the generation.”

Some kiruv professionals posit that the Modern Orthodox community is uniquely situated to engage in outreach.

“ Te Modern Orthodox community is no diferent professionally in many ways than many of the unafliated Jews we’re looking to attract. We’re also doctors. We’re also orthodontists. Te guy you would be learning with looks just like you,” says Rabbi Broide.

“It’s a much easier shif for someone to envision themselves coming closer to Judaism when it seems to be doable within their comfort zone,” says Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, co-director of OU-JLIC at University of California-LA (UCLA).

“ Tey can say, ‘I see my colleague or classmate doing this; maybe I can do it, too.’”

Rabbi Kaplan believes it would go a long way if Orthodox students proactively reached out to other Jewish students and created a welcoming atmosphere on college campuses.

“Your typical Orthodox teen from Pico Robertson in Los Angeles, or Teaneck, New Jersey, doesn’t know nonobservant kids,” he says. “Everyone is Orthodox around them. But in college, this is their moment—now they’re meeting [non-Orthodox Jews].”

A simple way anyone can help spread Torah to less afliated Jews is by contributing fnancially to

outreach programs. Without fnancial backing, even the most idealistic kiruv professionals cannot reach the many Jews who are looking for a connection to Judaism.

For example, NCSY’s JSU program for public high school students reaches thousands of teens each year. But according to Devora Simon, national director of JSU, there are roughly 350,000 Jewish kids in non-Jewish high schools in North America. “Based on the soaring interest in JSU programming, we know we can be reaching exponentially more teens,” says Simon.

JSU has seen a huge spike in the number of requests for new clubs since October 7, and JSU has tried to accommodate as many teens as possible. Unfortunately, stafng remains a huge obstacle. “I’m getting requests from places like Nashville, Vermont and Salt Lake City,” she says. “It’s hard to get people to move to more remote places. We are building out a robust system and platform to engage teens remotely, and empower them to lead in their communities, but we need the infrastructure and staf to support the program and manage these relationships.”

Many outreach professionals feel that in the post–October 7 world, the Orthodox community must prioritize Jewish outreach when allocating tzedakah funds. “It’s heartbreaking what teens are dealing with in school every day,” says Simon. “ Tese are young people in ofen hostile or unwelcoming environments who need us to be there for them. We simply need the resources to take care of these Jewish teens.”

to spread positive messages and have an impact on a wider network.

“If the bad news on social media is all people are seeing, it’s depressing,” notes Rabbi Mark Wildes, founder of Manhattan Jewish Experience (MJE). “So let’s not talk about why people hate us. Let’s highlight what’s positive.” He suggests providing a counterbalance in people’s feeds—showing all the good things that are part of the Jewish community—for example, Shabbat, trips to Israel, the remarkable chesed that takes place. “Our job needs to be bringing light into the world.”

Well before October 7, communal organizations like the OU and others have been making sure there is infrastructure in place to serve Jews across the country, says Rabbi Kaplan. Because of that, he says, young Jews who are searching for community

Rachel Schwartzberg is a writer and editor who lives with her family in Memphis, Tennessee.

Aside from providing fnancial support, individuals can act as ambassadors on behalf of Torah Judaism. Social

People are looking.

What are our communities doing to open those doors to the greater Jewish community?

have an address to turn to. “Whether it’s NCSY or OU-JLIC, we are where young American Jews are,” he says. As a result, “there are many more opportunities, because we’re already here to facilitate. If people are ready to jump, we’re ready to catch them.”

But despite all the kiruv programs and initiatives, more needs to be done on the communal level. Every shul, in fact, has a role to play, say experts. “People are looking. What are our communities doing to open those doors to the greater Jewish community?” asks Rabbi Broide. Every shul, he maintains, should have at least one outreach program. And while the programs might be diferent for each shul, depending on the population, he believes the core ingredients have to be there. “It has to be warm and welcoming,” he says. “We have something real. We have something special. What are we doing

to invite the broader community to be part of it?”

Shuls can help promote programs such as Partners in Torah, a highly successful initiative where participants get to study one on one over the phone or on Zoom with a mentor chosen especially for them. In Boca Raton, Rabbi Broide oversees a diferent initiative called Partners in Jewish Life. Instead of being over the phone or via Zoom, partners meet in a large space where they study prepared sources focused on the popular teachings of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks. Te curriculum, currently used in six shuls around the country with many more interested, resonates strongly with Jews from all backgrounds.

“ Tis program might not have worked a few years ago because people were in their own lanes—it’s my shul, it’s my Federation, it’s my JCC,” says Rabbi Broide. “But since October 7

Jews are looking to connect to the larger Jewish community.”

Now that the interest is burgeoning, kiruv professionals are asking difcult questions: If Jewish kids want to attend an Orthodox Jewish day school, can we accommodate them? If Jewish families want to start attending an Orthodox synagogue, are our shuls welcoming enough?

“No Jew lef behind—every single Jew should have an opportunity to interact with Jews who are a part of the formal Jewish community,” says Rabbi Broide.

Te central question Rabbi Broide and many others in the kiruv world are asking is: Are we—the Orthodox community—prepared for this?

By Rabbi Lawrence Kelemen

Generally, we think of Jewish religiosity as a two-dimensional scale stretching from secular to religious, with tick marks indicating levels of a composite of faith and mitzvah observance. We conceptualize teshuvah as movement across this scale, from less to more. But on October 7, a spiritual sea change seemed to sweep across our people that rendered this model simplistic.

We know that within days of the war’s outbreak, thousands of Israelis living all over the world streamed home. Tey came from Africa, Asia, Australia, North and South America, nearly every country in Eastern and Western Europe, the Caribbean and any other paradise that wanderlust could take a person. Except for the

Israeli national carrier, El Al, every airline canceled all fights in and out of Israel, not just because there was military action in Gaza, but because they assumed no one in their right mind would buy a ticket. But returning Israelis flled every (scheduled and unscheduled) El Al fight, chartered planes, and played international hopscotch in a counterintuitive efort to run into the war zone as quickly as possible. “Everyone is coming. No one is saying no,” said Yonatan Steiner, twenty-four, who few back from New York, where he works for a tech company, to join his old army medical unit. “Tis is diferent, this is unprecedented,” he said, speaking by phone from the border near Lebanon where his regiment was based.1

And even if this could be attributed

to IDF military reservists’ loyalty to their former units, that wouldn’t explain why more than 20,000 Jews from around the world made aliyah since the war began; or why many times that number fled papers to begin the immigration process, some of whom had never stepped foot upon the Land before applying to permanently relocate to a country under siege.2

Without any prodding or guidance from the Israeli government or Jewish communal organizations in the Diaspora, individual Jews spontaneously procured and delivered vital equipment for the IDF. Between October 2023 and January 2024, they bought, packed, and shipped more than 10,000 pairs of combat boots worth upwards of $850,000.3 El Al was carrying 100 to 200 dufels a week

Above: Without any prodding or guidance from the Israeli government or Jewish communal organizations in the Diaspora, individual Jews spontaneously procured and delivered vital equipment for the IDF. Courtesy of the IDF Spokesperson’s Ofce

just flled with boots. By June 2024, individual Jews from around the world had provided their Israeli brothers and sisters with an estimated $1 billion in helmets, drones, night vision goggles, body armor, rife scopes, kneepads, pocketknives, gun straps, tactical gloves, fashlights and other vital equipment. Tese were beyond the generous donations from the Jewish Federation and many other institutions. It was as grassroots as grassroots gets.4 Support didn’t just fow in from the Diaspora. According to a Tel Aviv University/Ben-Gurion University joint study, within the frst month of the war, 60 percent of Israel’s population made charitable contributions to the war efort, providing cash, blood, breast milk, hospital and rescue equipment, and anything else they thought their people on the front needed. Physicians, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, psychologists, professional chefs, drivers, mechanics and thousands of others with vital skills started working volunteer shifs in addition to their day jobs. Te same TAU/BGU study found that 41 percent of Israelis volunteered in this way. Starting the day afer October 7, kindness fowed bidirectionally between Israel’s religious and secular populations. For example, a week into the war, many Tel Aviv restaurants became kosher so they could provide meals for the religious minority in the army. Ten, in an unexpected twist, thousands of soldiers who considered themselves secular before the war requested tzitzit, and religious men and women all over the country went to work dyeing 60,000 shirts army-

Rabbi Lawrence Kelemen is rosh kollel of Ohr Chodosh in Yerushalayim. ArtScroll recently published Questions and Answers with Rabbi Leib Kelemen: Delving into Essential Matters on Faith, Practice and Hashkafah, where he addresses nearly 100 questions on topics ranging from shidduchim to childrearing, from Torah study to nurturing one’s talents, from shalom bayit to connecting to Hashem. Rabbi Kelemen’s lectures are available at www.lawrencekelemen.com.

A few weeks after October 7, posters that read, “There is no left and there is no right” went up in cities across Israel. It was one of the most refreshing ad campaigns ever.

green, tying onto them 60,000 sets of white strings, and delivering them to the fronts.

Were we just witnessing an outpouring of appreciation and support for the army? Tat wouldn’t explain why only a few weeks into the war religious Jews in Modiin, Rechavia, Beitar and other Orthodox neighborhoods started standing at intersections in adjacent secular neighborhoods handing out Shabbat candles, Kiddush wine and homebaked challot, or—even more curiously—why their secular neighbors stopped to accept the packages and express mutual afection. By March 2024, Jews were giving other Jews over 1,000 of these Shabbat packages a week. And apart from the paper bags that were donated by a couple of large organizations, all the costs were borne by the same nonprofessionals who shopped for the candles and wine and baked the challot Tis was spontaneous and grassroots. When asked why people from such diferent demographics were all so excited about this giving-and-receiving initiative, a Chareidi woman from Moshav Matityahu told me, “ Tis is called unity, brotherhood and connection.”

Te day afer October 7, Kesher Yehudi, an Israeli nonproft, was swamped by demand for their chavruta program, which introduces secular and religious Israelis to each other. Tousands of requests poured in from both cohorts, not primarily for opportunities to learn or teach Torah, but to grow a long-term friendship with someone from a diferent background. A Kesher Yehudi administrator told me that afer October 7, the weekly

to the mourners who gather there daily. Tere were parents, children, brothers, and sisters tending to makeshif memorials for their slaughtered relatives. An apparently secular woman took a sack of white stones out of her car and started arranging them around a stake planted in the ground with a picture of her deceased son. We ofered to help her. She didn’t look at us, but conveyed appreciation. When we were done placing the stones, we stood in silence for a few minutes, and then one of my students asked the mother if we could say Kaddish for her son.

“I lost my faith a long time ago,” she whispered, staring at the ground.

“How about Kel Malei Rachamim?” She was crying, but nodded to indicate that would be okay. When we fnished reciting Kel Malei Rachamim, we were all crying. She remained standing with us for a while. Ten another one of my students whispered to the mother again, “Would you like us to say Kaddish?” She made eye contact with us for the frst time, scanned our faces, and then said, “Yes, please.” It is possible that when she scanned our faces, she saw something familiar. I will try to explain.

Teshuvah might be a broader, deeper process than just movement from less-to-more mitzvah observance. In a cryptic comment on a Talmudic passage (Avodah Zarah 19a), Rashi defnes teshuvah as “l’hakir Bor’o—to recognize one’s Creator.” Avraham Avinu’s teshuvah process illuminates what the word “recognize” might mean here. According to the tradition, at age three Avraham knew there was a G-d, but by age forty he progressed from knowledge to recognition (Rambam, Hilchot Avodah Zarah 1:3). Te Hebrew word for recognizing G-d (hakarah) implies more than just knowing (yediah) that there is a G-d. One who who only “knows” that G-d exists can still view Him as foreign and unrelatable. Recognition implies familiarity. By age forty, Avraham saw something familiar in G-d—his own Divine image. “From himself Avraham recognized the Holy One” (Bamidbar Rabbah 14:2).

Every member of the Jewish

nation had such an experience at the Yam Suf. Tere each individual sang (Shemot15:2), “Tis is my G-d, v’anveihu.” Rashi (Shabbat 133b) translates anveihu literally as “ani v’hu—me and Him.” At the Yam Suf, every individual saw his or her own potential in the Holy One and yearned to bring forth that potential and become like Him.

Eventually, the recognizing-G-d type of teshuvah could lead to the mitzvah-observance type of teshuvah. How? People who want to become similar to G-d may notice the thread connecting all of His behavior. A verse in Tehillim (147:19) reads, “He tells His commandments to Jacob, His statutes and decrees to Israel.” Our tradition (Shemot Rabbah 30:9) asks why the mitzvot that G-d commanded to us are called His Tey should be ours Te Midrash answers: “What He does, He also tells Israel to do ” In some unfathomable way, G-d keeps all the mitzvot, and for us to bring forth our Divine potential we must keep the mitzvot too. Te Torah is a G-d-given system for self-actualization. Avraham Avinu recognized G-d and understood that the mitzvot are Divine behavior, and so he took upon himself all the mitzvot as well (Yoma 28b).

Knowing that G-d exists but not recognizing Him leads in the opposite direction. Healthy people not only intuitively sense their uniqueness but feel a need to express it. Tis human drive to self-actualize can be as strong as the desire to pursue life itself. If someone threatens another’s freedom to self-actualize, most people will fght back. Rashi teaches that both Nimrod (Bereishit 10:9) and the citizens of Sodom (ibid., 13:13) knew G-d existed, but felt no commonality with Him, and so they rebelled. So did many Jews throughout history.

Tis gets deeper. Perhaps Jewish unity and teshuvah are interlinked. Te more thoroughly one recognizes the Creator, the more obvious it becomes that He has multiple manifestations (Sanhedrin 37a): “When a person stamps several coins with one seal, they are all identical. But the supreme King of Kings, the Holy One, Blessed

be He, stamped all people with the seal of Adam, and not one of them is similar to another.” Every Jew possesses in potential one unique aspect of G-d’s complex Divinity. Te more the individual brings forth his unique tzelem Elokim, the more he recognizes his own identity in the Holy One. At some stage in the teshuvah process, one may recognize in G-d not only one’s own unique potential but others’ very diferent potentials as well. Tis means more than just tolerating other Jews. It involves acknowledging that our diferences may stem from a common Divine Source. It is a state of mutual responsibility, appreciation, afection and even connection. It is a place where diversity and unity become inextricably bound together in the Divine ideal. Tat morning at the Nova site, my students and I recognized something familiar in a mourning mother, and she recognized something familiar in us. Diferences like religious and secular, lef and right, Israeli Jew and Diaspora Jew, all seem insignifcant compared to the Divine image in us all. Tis feels like the teshuvah that many Jews are experiencing post October 7.

Notes

1. Helen Coster and Alexander Cornwell, “Israel’s reservists drop everything and rush home,” Reuters, October 12, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/ middle-east/israels-reservists-dropeverything-rush-home-following-hamasbloodshed-2023-10-12/.

2. “22,000 Jews Have Made Aliyah Since October 7, Jewish Agency Reports,” Yeshiva World, July 17, 2024, https:// www.theyeshivaworld.com/news/israelnews/2297264/22000-jews-have-madealiyah-since-october-7-jewish-agencyreports.html

3. Sharon Wrobel, “Something is afoot: Volunteers ft IDF soldiers with US military boots amid Hamas war,” Times of Israel, January 14, 2024, https://www.timesofsrael. com/something-is-afoot-volunteers-ftidf-soldiers-with-us-military-boots-amidhamas-war/

4. Asaf Elia-Shalev, “Six months into war, Israeli soldiers still count on donations for basic supplies. Why?,” Times of Israel, April 25, 2024, https://www.timesofsrael.com/sixmonths-into-war-israeli-soldiers-still-counton-donations-for-basic-supplies-why/.

Gaucher Disease type 1 (GD1) bone damage may be progressing without you realizing.

Taking control of your GD1 through early management is key to potentially avoiding severe, irreversible bone damage.

LEARN MORE

With the first anniversary of October 7 approaching, we asked readers to tell us how they were impacted by a day that will live on forever in our hearts and souls.

n the afermath of October 7, I am living my Judaism in a much more open way, wearing a Magen David necklace, studying Jewish history and feeling more connected to Israel as our indigenous homeland. I think about aliyah. I did not grow up Orthodox and my ex-husband isn’t Jewish. But since October 7, I’ve tried to have a daily infusion of Judaism in my life and in my children’s lives.

A few days afer the massacre, I saw a post for a program called

“Just One Ting,” in which you try to do one Jewish thing in the merit of a specifc soldier. I began saying Shema every night along with a Mi Sheberach for “my” soldier, and I started bringing in Shabbat ffeen minutes early.

I signed up with Partners in Torah as a merit as well. I was paired with Raquel from New York and felt that I’d found my sister. We study the teachings of the late Rabbi Jonathan Sacks on the parashah. October 7 changed my

relationship to Judaism, to the nonJewish world, to Israel, to parenting, to everything.

To me, the response to October 7 is to live more Jewishly.

By Ariella Silberman, as told to Barbara Bensoussan. Ms. Silberman lives in Dallas with her family. Ms. Bensoussan is a writer in Brooklyn and a frequent contributor to Jewish Action.

’m a marketing professional, so social media is my bread and butter. Afer October 7, as I scrolled through X, I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. “You Jews deserve it,” some people wrote. “Stop occupying Palestine!” said others.

Te haters clearly had no grasp of the facts. How do you counteract a food of anti-Israel narratives that have more likes on social media than a cat meme?

I sat down and began replying to these posts. But I’m no Ben Shapiro—I don’t have all the facts on the tip of my tongue. Afer an hour, I realized I’d only managed to reply to about four posts. Tere were hundreds of posts I wanted to respond to!

Ten it occurred to me that I could enlist virtual help. I’m a typical Flatbush guy who runs a no-frills ad agency out of a Brooklyn storefront. Recently, I’d begun using AI tools for marketing campaigns in my business. Why not create an AI engine to give factual, cohesive responses to social media? I thought. Why not harness the power of AI to negate the hate?

was born in Chicago eighty-seven years ago.

In the 1930s and ‘40s, as the Holocaust was unfolding, I would listen to my American-born parents speaking about the German atrocities and about the Jews sufering in Europe.

But back then children were supposed to be quiet.

Dad was drafed into the US Army when I was six years old. He was captured by the Nazis and sent to a slave labor camp for Jews only. He was liberated and, thank G-d, came home.

I posted my idea on LinkedIn and on a few WhatsApp groups. Almost a dozen people from diferent points on the Jewish spectrum volunteered to help: a Chassidic developer in Toronto; a non-religious Sephardic full-stack coding engineer in Tel Aviv; a Modern Orthodox copywriter in Teaneck.

Our group held sessions on Zoom to create the app. Te goal was to train a data set to give forceful, factbased, pro-Israel responses to hate posts, circumventing systemic blocks to pro-Israel content. Afer four sleepless, cafeine-powered days, we had an app called ProjectTruthIsrael. com up and running.

I said to our group, “Under other circumstances, our paths would probably never have crossed. Yet here we are, all of us fellow Jews, giving our time and resources to help the Jewish nation.”

I sent out our app experimentally to a bunch of Jewish WhatsApp groups, expecting to garner a few hundred responses. Within one night, I had 3,000 users. Afer one month, 41,000 people were using the app, generating over 80,000 response points.

We were not religious, and did not observe any holidays except for Passover. We never belonged to a synagogue.

October 7 made me feel more Jewish. I felt I had to do something for the Jewish people. I realized I had to speak up.

Now I spend my time on Facebook and Instagram, sharing pro-Israel videos on a daily basis.

I bought a siddur with English translation; I don’t read Hebrew. I bought more Jewish books. I’m paying more attention. I must. I

Te app was really working well, churning out compelling factual messages to counteract misinformation and antisemitism. Ten, a few weeks ago, I opened my computer on Motzaei Shabbos to fnd a message: “Your AI token threshold is over the limit.”

“Hacktivists” from the Middle East had bombarded our site to the point where they shut it down. I have been working ever since to fnd a way to get my site up again and circumvent further attacks.

Despite this (hopefully temporary) setback, I am very proud of what we accomplished. While we made a small dent in the social media world, I think we made a much bigger dent in the heavens: a diverse group of Jews came together to help our brothers and sisters in Israel.

couldn’t speak up in the 1930s as the Holocaust approached, so I’m speaking up now on behalf of Israel and my fellow Jews.

By Maxine

Clamage, as told to Steve Lipman. Ms. Clamage is an eighty-sevenyear-old retired paralegal living in Mill Valley, California. Mr. Lipman is a frequent contributor to the magazine.

s I sat on a plane to Israel last winter, October 7 was fresh in everyone’s minds. I knew there were thousands of sufering families—victims of terror, victims of tragedies, and families who had been forced to abandon their homes and livelihoods. I wanted to do something.

I work as a physician in Williamsburg, with a largely Chassidic and Hispanic clientele. My work has led me to become involved with Miles for Life, an organization that funds medical travel for foreign patients who need to come to the US for medical care. I am ofen asked to write statements attesting to the necessity of medical travel so that patients and their accompanying caregivers can apply for visas. Miles for Life collects unused travel and credit card points from donors to pay for the patients’ travel.

While on the plane, I thought, “If we can use points to beneft

patients from South America and other countries, why not use them to help Jews ravaged by the war in Israel?” It seemed like an easy, costfree way to give tzedakah and lend support to our brethren in Israel who desperately need it.

Te fight passed quickly as I sketched out a plan. I didn’t want to fund trauma relief only. Life goes on afer trauma, and challenged families still need to make simchas and celebrate holidays even when the usual funds have dried up. I wanted to channel unused miles and points to fund bringing joy into difcult lives. I was sitting next to an accountant who became so interested in my idea that he stayed in touch to check on my progress afer I got home!

Simchapoints.org, now under the Chibuk Foundation, is open for business, with the aim of helping challenged Israeli families aford the bright spots in their lives: bar

When October 7 happened, I was a high school teacher in a non-Jewish charter school in Brooklyn. In the days that followed, we were given a mandatory curriculum for our advisory students that sought to “contextualize the confict” and denied any historical ties between the Jewish people and their ancestral homeland prior to the nineteenth century. As a direct result, I started looking for new, meaningful work, ways I could invest my time and energy into the Jewish world. I was lucky enough to be hired to write security grants by Project Protect, a division of the OU’s Teach Coalition,

which secures and implements government funding to protect our Jewish institutions. Trough this job I’ve had the privilege to talk to stakeholders across the entire spectrum of Jewish communal life, fnd out their histories and the risks they face in their neighborhoods, and help them address their urgent need for safety. Tis work has been a profound source of personal pride for me and has made me feel more connected to the Jewish nation than I ever felt before.

As I write, a week from today I will have my interview with the Jewish Agency, and, G-d-willing, I will be making aliyah shortly. My

mitzvahs, weddings, yamim tovim, even camps for their children. Donors can earmark funds for a specifc event—for example, a family making a bar mitzvah can donate money for an Israeli family’s bar mitzvah expenses.

Before we Jews were the Startup Nation, we were the “Chesed Nation.” October 7 opened our eyes to the need to empathize with our fellow Jews in Israel and extend a helping hand as best we can.

By

greatest hope is to continue doing this security work for the Jewish community here in the United States while fnding new ways to connect and give of myself in whatever way I can in Eretz Yisrael. Before October 7 and its afermath, I did not understand the overwhelming imperative of achdut and ahavat Yisrael. While I’m ashamed it took something so evil to teach me, I will never forget the lesson.

Explore intriguing topics such as:

• How and why is Talmudic law binding?

• Which parts of the Talmud were received at Sinai?

• How and when can Talmudic law be amended?

• Fundamental distinctions between Sephardi and Ashkenazi Talmudic methodologies

• Can academic Talmud study enter the Beit Hamidrash?

“Comprehensive…well researched… scholarly, interesting, and clear, and I am sure so many will benefit from reading it.”

Rav Yitzchak Berkovits

“Talmud Reclaimed can ofer insight to everyone who studies Talmud…”

Professor Chaim Saiman

“A very impressive work on many levels…helpful both to the novice and to the seasoned Talmid Chacham… Rabbi Phillips has already authored a masterful book, Judaism Reclaimed, which received wide acclaim. He has in my judgment surpassed himself with this book.”

Rav Yitzchak Breitowitz

When we learned that October 7 survivors, most from secular and antireligious kibbutzim, were staying in a hotel near our Chareidi town, a group of us drove out to see them. At the hotel door, a social worker barred our entry: “Tey don’t need anything. Go.”

We went home crestfallen and puzzled.

Was there really nothing to do?

Ten one of us had an idea: “Let’s send them challah rolls, candles and notes of support.”

A WhatsApp message went out, and dozens of volunteers responded. By erev Shabbat we had received so many packages that we needed additional volunteers to deliver them to the hotel.

We lef them with the hotel staf. But we weren’t sure. Would our lovingly assembled packages end up in the trash? Had we mobilized the entire community for nothing?

When we returned days later, we found out that our packages had indeed been delivered.

“We ate them,” said an elderly male evacuee, “but don’t send them again.” Our gesture had fallen on its face. Was there something else we could do? “Yes,” a heavily tattooed kibbutz woman piped up. “We can use four cakes every day for our cofee room.” Tat was clear enough. Since then, we have been baking and sending our

Icakes to evacuees—yeast cakes, kokosh cakes, batches of cookie bars, et cetera. Te cakes are delivered to a central collection point, where volunteers pick them up and deliver them.