8 | The Jewish Press | February 5, 2021

Voices

The Jewish Press (Founded in 1920)

Abby Kutler President Annette van de Kamp-Wright Editor Richard Busse Creative Director Susan Bernard Advertising Executive Lori Kooper-Schwarz Assistant Editor Gabby Blair Staff Writer Mary Bachteler Accounting Jewish Press Board Abby Kutler, President; Eric Dunning, Ex-Officio; Danni Christensen, David Finkelstein, Candice Friedman, Bracha Goldsweig, Margie Gutnik, Natasha Kraft, Chuck Lucoff, Eric Shapiro, Andy Shefsky, Shoshy Susman and Amy Tipp. The mission of the Jewish Federation of Omaha is to build and sustain a strong and vibrant Omaha Jewish Community and to support Jews in Israel and around the world. Agencies of the Federation are: Community Relations Committee, Jewish Community Center, Center for Jewish Life, Jewish Social Services, and the Jewish Press. Guidelines and highlights of the Jewish Press, including front page stories and announcements, can be found online at: wwwjewishomaha. org; click on ‘Jewish Press.’ Editorials express the view of the writer and are not necessarily representative of the views of the Jewish Press Board of Directors, the Jewish Federation of Omaha Board of Directors, or the Omaha Jewish community as a whole. The Jewish Press reserves the right to edit signed letters and articles for space and content. The Jewish Press is not responsible for the Kashrut of any product or establishment. Editorial The Jewish Press is an agency of the Jewish Federation of Omaha. Deadline for copy, ads and photos is: Thursday, 9 a.m., eight days prior to publication. E-mail editorial material and photos to: avandekamp@jewishomaha.org; send ads (in TIF or PDF format) to: rbusse@jewishomaha.org. Letters to the Editor Guidelines The Jewish Press welcomes Letters to the Editor. They may be sent via regular mail to: The Jewish Press, 333 So. 132 St., Omaha, NE 68154; via fax: 1.402.334.5422 or via e-mail to the Editor at: avandekamp@jewishomaha. org. Letters should be no longer than 250 words and must be single-spaced typed, not hand-written. Published letters should be confined to opinions and comments on articles or events. News items should not be submitted and printed as a “Letter to the Editor.” The Editor may edit letters for content and space restrictions. Letters may be published without giving an opposing view. Information shall be verified before printing. All letters must be signed by the writer. The Jewish Press will not publish letters that appear to be part of an organized campaign, nor letters copied from the Internet. No letters should be published from candidates running for office, but others may write on their behalf. Letters of thanks should be confined to commending an institution for a program, project or event, rather than personally thanking paid staff, unless the writer chooses to turn the “Letter to the Editor” into a paid personal ad or a news article about the event, project or program which the professional staff supervised. For information, contact Annette van de KampWright, Jewish Press Editor, 402.334.6450. Postal The Jewish Press (USPS 275620) is published weekly (except for the first week of January and July) on Friday for $40 per calendar year U.S.; $80 foreign, by the Jewish Federation of Omaha. Phone: 402.334.6448; FAX: 402.334.5422. Periodical postage paid at Omaha, NE. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: The Jewish Press, 333 So. 132 St., Omaha, NE 68154-2198 or email to: jpress@jewishomaha.org.

American Jewish Press Association Award Winner

Nebraska Press Association Award winner 2008

National Newspaper Association

Editorials express the view of the writer and are not necessarily representative of the views of the Jewish Press Board of Directors, the Jewish Federation of Omaha Board of Directors, or the Omaha Jewish community as a whole.

We remember

ANNETTE VAN DE KAMP-WRIGHT Jewish Press Editor Jan. 27 was International Holocaust remembrance Day, which always makes me wonder: what is different about that day, versus all other days? That one day, when candles are lit, special commemorations are held around the world, does it really make enough of a difference? The next day, most people go back to life as they know it—I have to ask whether it really makes an impact. For most people, I’m afraid the answer is ‘no.’ Even if they pay attention on the day itself, maybe post something on their social media or even attend (virtually, in this case) some event somewhere, even if in theory they agree remembering is important, it does not always translate into action the other 363 days. Take for example the speech delivered by Valdis Rakutis, who is a member of the Seimas, Lithuania’s parliament, and chairman of its commission on historical memory. ““There was no shortage of Holocaust perpetrators among the Jews themselves, especially in the ghetto self-government structures,” Rakutis said in the speech, which took place on International Holocaust Remembrance Day. “We need to name these people out loud and try not to have people like them again.” “Rakutis also said that two wartime collaborators with Nazi Germany, Kazys Škirpa and Jonas Noreika, were not to blame for the fact that more

than 95% of Lithuanian Jewry was murdered, mostly by locals and often by followers of the two leaders.” (JTA.com) I want to be surprised, but I’m not. Rakutis is hardly the first European politician to stick his foot in his mouth; it’s happened all over the continent, in Great Britain, in North and South America, you

name it. The archetype of the politician who accidentally (or sometimes not-so-accidentally) admits how truly anti-Semitic their thinking is has become commonplace. Why even attend a Holocaust commemoration if you are going to say these things—and why attend if you believe these things? I don’t know the answer to that. I do know that as Jews we approach these commemorations in the hope to educate, the hope it will make a difference. Every day, that hope becomes more urgent, as many survivors are leaving us and it is up to us to

keep the memories alive. Marking one day a year is obviously not going to do it. We need more, we need a constant, living memory. The ADL recently wrote: “Holocaust denial, is founded on stereotypes of Jewish greed, scheming, and the belief that Jews can somehow force massive institutions — governments, Hollywood, the media, academia — to promote an epic lie. In the United States, until the early 2000s, Holocaust denial was dominated by the extremist right, including white supremacists, who had a vested interest in absolving Hitler from having committed one of the most monstrous crimes the world has ever known. Today, Holocaust denial in the U.S. has moved far beyond its original fringe circles on the extremist right to become a phenomenon across the ideological spectrum. A September 2020 survey found that 49 percent of American adults under 40 years old were exposed to Holocaust denial or distortion across social media.” (ADL.org) That is a scary truth, but it’s one we have known for quite a while: those who distort and deny the Holocaust are much busier and much more effective than those who want to educate and speak truth. If you believe it’s all a lie, you get rid of the guilt—and that is an attractive notion to many. One day to remember is obviously not enough. Most of us remember the Holocaust every day-it’s how we were raised. It’s time the rest of the world does too.

My grandfather survived Auschwitz and spends his life spreading kindness HANNAH ALBERGA JTA On Jan. 6, a sea of heads bobbed and flags flew outside the U.S. Capitol. A closer look revealed a dark hoodie, skull, crossbones and large white letters: “Camp Auschwitz,” followed by “Work Brings Freedom.” That’s the phrase my 91-year-old grandfather, David Moskovic, saw every day in German, “Arbeit Macht Frei,” when he was a 14-year-old Nazi prisoner. For nights following the riots, my grandfather roused to recurring nightmares. The mob at the Capitol brought him back to Auschwitz, 1944. Upon arrival, soon-to-be prisoners were rushed out of cattle cars and had their belongings taken. Everyone was sorted into two lines: One led to a building with a chimney exhaling bulging smoke; the product of cremating innocent bodies. One led to the camp. His family was split, but by the end of the war he lost everyone:his mother, father, older brother, two younger sisters but not his older sister, Edith. “You can’t even comprehend what could have happened,” he said to me over the phone from Ottawa when we spoke about the riots. But he could. He knew what hate-born violence looked like, felt like, the pain, the starvation, the loss, the imprint. Today, on Holocaust Remembrance Day, it’s imperative to step into the past as a way to process the present. At 16, my grandfather had suffered more than most people do in their entire lives, but he never let it define him. Instead it fueled a deep, wholehearted sense of kindness that guided the rest of his life. Following his arrival at Auschwitz, my grandfather, along with his brother and father, was tattooed with his new name — A6024. David Moskovic no longer existed. For six months he was sent to lay bricks at Buna, a work camp outside of Auschwitz. His daily diet consisted of a slice of hard bread, grass soup with stones mixed in and sometimes a thicker potato soup for dinner. He often saved his slice of bread for his father, terrified for his diminishing body and declining health. In January 1945, Buna prisoners were rounded up at dusk and instructed to march. Gunshots pierced the air. Prisoners dropped dead. After three days without food or water, they arrived at a brickyard in Glewice, a village in Poland, and were given a slice of bread before being jammed into cattle cars. Each

time the train stopped, the soldiers removed dead bodies, but my grandfather needed these corpses. He hid beneath them as a blanket. When it snowed, he kept his mouth open to dampen his lips. Later he learned that his father and brother had died. By the fourth day without food or water, the cattle car stopped at Buchenwald, a concentration camp in Germany. My grandfather rolled off, unable to stand. He saw his uncle dying but did not react, could not react. Survival was the sole focus. Each day he pleaded to God, “Give me one more day.”

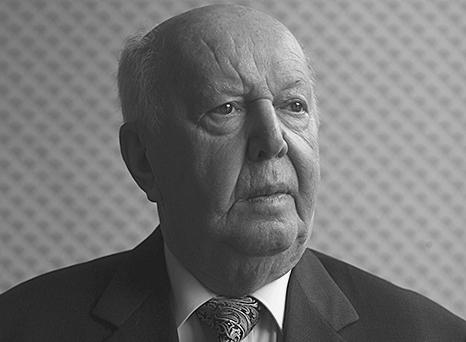

David Moskovic, the author’s grandfather, at his 90th birthday party. Credit: Stephen J. Thorne

Finally he was fed a bowl of soup. He snuck back in line for seconds — a death sentence if discovered. When he saw prisoners on the verge of dying, he took their food vouchers. This was the only way to survive. He was so skinny he could practically see through his own hand. All that remained was skin and bones. As the Allies encroached, the Nazis tried to kill as many people as possible. They selected hundreds of prisoners every day, instructed them to dig a large hole and shot them into the mass grave. One day, my grandfather was chosen. He knew once he left those gates he would never return. No one did. As the selected prisoners began to march, he threw himself to the ground and lay flat while the others stepped on him. Once they left, he ran back to his barrack, hiding in the rafters for hours. On April 11, 1945, planes flew so low it seemed like they would hit the roofs of the barracks. My grandfather could barely walk outside to see what was going on. A big white sheet hung in the air. The guards were gone. American soldiers had arrived. When I place the picture of American soldiers liberating my grandfather, handing him the most valu-

able gift imaginable at the time — freedom — next to the U.S. Capitol rioters, I feel nauseous, my muscles tighten and my jaw clenches. The contrast is uncanny. But it’s a testament to reality. Freedom and hate live in tandem, immersed in a tumultuous relationship: When one pushes, the other pulls. White supremacy is alive. But my grandfather is alive, too. The Capitol mobs represent a hatred that was growing louder every day. But my grandfather and other survivors represent a love that has the extraordinary power of sowing hope for “one more day.” Auschwitz is not a historical artifact. The gates did not close on liberation day; they opened a door to generations of hate that may never have an expiration date. But they also opened the door to freedom for my grandfather, who reminds me that every day is beautiful. He lost his family, his home, his health, his nationality and religious identity. Yet he started over. The past never tainted his future, but instead showed him a path of resilience. Love became the cornerstone of his life; a sharp contrast to the hate-filled wishes of white supremacists. Living in Ottawa, while working as a plumber, he dropped off and picked up his three children every day from school, no matter what. He traveled eight hours round trip from Ottawa to Toronto for my school plays, graduations, birthdays, holidays and often just for a visit. He welcomed a new rabbi by delivering a Shabbat meal. He gifted my cousins’ old toys to children he met in the elevator of his apartment building. He extended an open-ended offer to take a blind woman for groceries. He made peanut butter sandwiches for the security guard in his building, toasted, just the way he likes it. His hugs are more like squeezes. His handholds can last hours. His kisses are on both cheeks. Before the pandemic, my grandfather regularly spoke at schools about his experiences. He often concluded with this sentiment, the same words he says to me at the end of every phone call: “I live a beautiful life. I have three beautiful children. I am a happy man. Be nice to each other. Be good to each other. Take care of each other.” Hannah Alberga is a Toronto-based journalist. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of JTA or its parent company, 70 Faces Media.