14 minute read

Juan Bolivar In Conversation

IN THE WEEKS PRECEDING ON THE ROAD AGAIN, JULIUS KILLERBY (JGM GALLERY'S ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR) VISITED JUAN BOLIVAR IN HIS NORTH LONDON STUDIO. THE VISIT WAS AN OPPORTUNITY FOR BOTH TO DISCUSS BOLIVAR’S WORK & THE UPCOMING EXHIBITION.

JULIUS KILLERBY So, Juan, in what ways does music find its way into your work?

Advertisement

JUAN BOLIVAR I first began introducing, or at least referring to, music in my work in an exhibition called Bat Out Of Hell (2011) at Jacob Island Gallery. It was the first time that I not only titled works after Rock songs, but I started making references to historical artworks. It’s an interesting coincidence that those two things overlapped. It was initially informed by the problematised use of music in combat, or in video games... you know, this kind of grey area for music... but then, as time has gone on, I’ve realised that there’s actually a tradition of musical elements being adopted by painters in the past. If you look at Vermeer, who often made musical references in his paintings, or Mondrian and de Kooning, who both owned records players ahead of their time, you get a sense that music is adjacent to the making of paintings, and its gradually formed a bigger role in my work.

JK So are you interested in how music changes the context of the thing it is presented with, or alongside?

JB Well I guess there’s that element, not of how music changes the context, but how it can contextualise something. I like, for example, the way that Adam Curtis, the documentary film maker, uses music to offset images. If one is thinking about music, then one almost has a different lens that you’re looking at your work through. I also like the way that music carries memories for people, and how it can take you back to certain points in your life. It’s also, in some sense, a way of referencing culture, in a way which not everybody will be familiar with but it can also have a universality.

JK Is music implied by the title and subject matter of this exhibition? Because large vehicles and the phrase, “on the road again”, at least for me, brings to mind the songs that I would listen to whilst on a road trip.

JB Yes, I’m using the idea of this imaginary soundtrack that somebody might be listening to on a long journey. The musical element functions as a metaphor for the idea of the “long-haul” and there’s this idea of the artist perhaps being on a similar long journey. It adds all these other associations to the idea of transportation. In my case, it’s the weight of the subject that I am dealing with. So, there’s this playful comparison being made with someone who is taking these metaphorical contents somewhere. I also like the idea that, in some ways, the whole analogy of being a truck driver is a bit like being in the studio where you have this almost hermetic environment. There’s also comparisons between the isolation of the road and the loneliness of the studio. Truck drivers, also, will often customise the interior of their cabin and it becomes this private space in the open world.

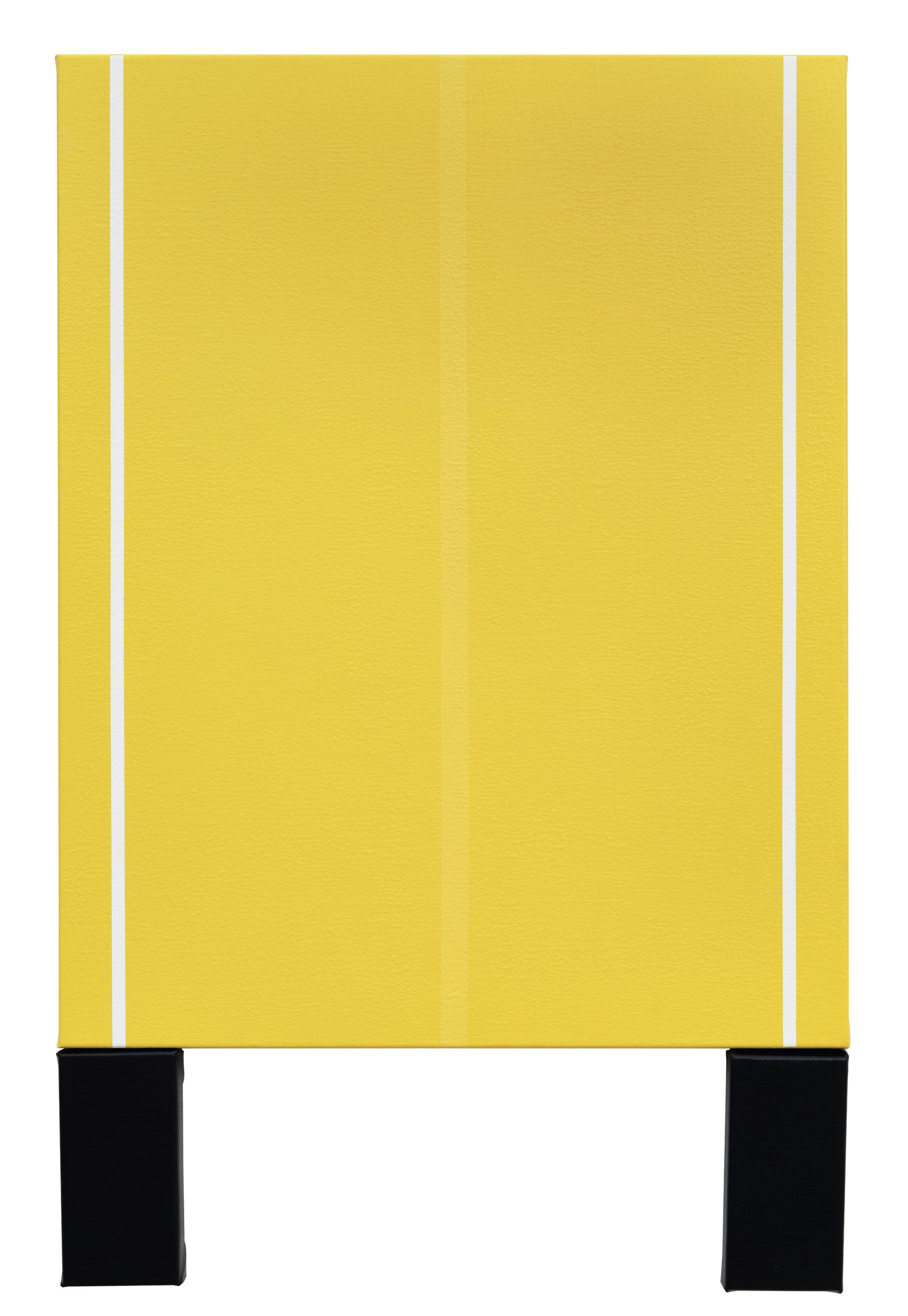

JK Why the solid application of paint? It seems almost as though you’ve removed the trace of the artist. Would you say that’s accurate?

JB There’s two parts to that question. And the first part, you’re absolutely right, the colour is almost supposed to be a physical material. It’s not like what I call Photoshop colour deceit, which are colours that don’t really exist anywhere, except as binary information. The colour, in my case, is almost meant to be something that you could bite into. I want to get from it as much sensation or pleasure as I can by applying it in a very solid block. I’m not sure if I necessarily agree with the other side of the question. There is a type of touch, of application. There’s a sort of tactility to it, but it exists in quite a narrow range. It’s not as though the tactility is coming out at you like a Frank Auerbach. There is texture in my work if you look a bit closer. You will find slight ridges, brush direction, or paint dripping down the edge of the canvas. That said, I’m less interested in this idea that touch defines the work. I almost like to hold back a bit, so that other things can come through. There’s a few other artists that share this relationship with a certain kind of block colour that is applied in a certain way. There’s Peter Halley who achieves a block colour, rolling 50 layers of acrylic paint for each section. There’s an artist who sadly passed away a few years ago called Sybille Berger and she used to apply something like a hundred layers of colour. Then there’s another artist called David Diao who applies solid colour with a palette knife, or will sometimes screen print the colour. I think we all, in some way, share that intrigue with something that looks solid and mechanical but actually has a specific expressive range.

JK Would you say that the unspoken rule amongst you and those artists is that the paint is not mixed on the surface.

JB That’s right, there’s no modulation. That’s a good observation. The colour would almost always have been pre-mixed and then applied. Yes, there’s no pendimenti or scraping.

JK How does On The Road Again differ from your last exhibition with JGM Gallery?

JB The last show at JGM was called Powerage. In that exhibition I re-enacted a lot of the works that I’m still referring to. You know, Modernist painting, Colour Field painting, artists like Barnett Newman, Kenneth Noland, Morris Louis. In that exhibition (Powerage), I was inserting mid-century cartoons and cartoon elements as if they were existing within those works. The main difference between that approach and this show is that I am now placing what I call “rogue elements” adjacent to the works, rather than within them. The work is being referenced in an unadulterated way but I am changing the way that we perceive it.

JK In a lot of the work you’ve combined canvases of variable dimensions and in fact this is how you often suggest form, whether it be a truck or something else. What are the conceptual implications of playing with the border of an artwork like this?

JB Yes, that’s an interesting question. I’ve always been drawn to the way an artist negotiates the borders. I like to see what happens on the edge of the illusion. Mondrian’s interesting in that we imagine his work as very graphic but if you look closely at it you’ll see that some lines stop short, or go just over the edge. It’s like he’s trying to draw our attention to the border of the painting. I think borders almost suggest that the painting exists within a specific dimension. There’s a book called Flatland by Edwin Abbott and in this book he describes a fictional two-dimensional world which is one day invaded by three-dimensional elements. It’s all meant as a kind of metaphor for Victorian society and power structures but the lasting legacy of this book is how it made people think about different dimensions. In my paintings, I’m thinking of this idea of intertextuality, about how the painting can take you somewhere else. I hadn’t really thought about it until you asked the question but I think that in this show the additional things that are outside the border point to that idea of expansion.

JK It’s interesting because generally in a reprentational painting, one paints on a flat surface to create an illusion of depth. Your paintings, in that two-dimensional space, have no illusion of depth. There is no tone. But you create depth and three-dimensionality by playing with these elements outside of the canvas.

JB Yes. I play with the idea that the paintings are quintessentially abstract but that, in the mind’s eye, they can flip and become forms for trucks or anything else for that matter. In some ways it’s like the 19th century Duck Rabbit illustration, where two forms are simultaneously suggested. I like the idea that my paintings are also almost Lego-like and are reminiscent of toys that we might have played with in our childhood.

JK Are your works, then, just as much sculptures as they are paintings?

JB Yes. I was watching an old de Kooning documentary where they were teasing de Kooning with a questions, with words to the effect: “What is a painterly artist?” and he answers with something like “Well, it’s an artist who wants to show the brush marks.” By that definition I do consider myself a painterly artist. There are probably other ways that these images could be made. They could be printed, they could be animations. They could be made in a way that distances the viewer from the mark. So there is an element of painterliness but I’m not really interested in conventional definition of painterly.

JK Do you think that colour, as an aesthetic element, is the closest visual analogue to music? I feel that tone, scale and texture are less equivalent to music than colour is and I wonder if, perhaps subconsciously, that’s why those elements - tone and texture in particular - are noticeably absent from your work. Or maybe I’m reading too much into this?

JB I’m always a bit suspicious of the word “aesthetic”. I think that paintings are really complicated and you never just look at one element. It’s like a whole experience that you kind of mix internally. I think that today I would probably never discuss colour in that way. I might’ve done once, but today I think of it more as something that I’m sampling. It’s closer to a film director’s approach. Tarantino, for example, always talks about mixing things. He takes one thing and adds another layer to it and that sort of throws us in different directions. I also like this idea in music of interpolation, of inserting something of a different nature into something else. Until the 19th century this was how a lot of music was made. There were existing passages or motifs that were borrowed and then new pieces would be written using those set structures. I think that in some way I’m doing something similar.

JK I agree that Tarantino is a great example of how the combination of different elements can generate something conceptually novel. There’s that scene in

Reservoir Dogs for example, where the policeman is being tortured while Stuck In The Middle With You (Stealers Wheel) is playing. It’s so perverse because it’s such a happy Rock ‘n’ Roll song and yet it’s being played while someone is having their ear cut off.

JB Yes and I guess what’s interesting is that we won’t know what these things mean until maybe one hundred years from now when the references are lost or forgotten. People won’t be able to locate or understand the references at that point so we will then see what we are left with. I find that interesting to think of how the work will live on. Already, some of the references in my work probably don’t register with the majority of my audience.

JK Art about art is a recurring subject for so many artists. I wonder at what point in Art History that became a thing.

JB Well I think that’s become more apparent but I also think that it’s actually always been like that. I think we always make things that build on something else. It’s probably slightly contentious but my view is that art is always about art.

JK Yes, perhaps we’re so far removed from periods like the Renaissance that we don’t see the references in their work. Are there artists who you’ve had a particular affinity for and who you’ve referenced more than others?

JB There’s so many really. There’s the Fayum mummy portraits, which I’m really fascinated with. There’s also Duccio, Fra Angelico, Piero della Francesca. I know it probably sounds really pretentious or cliché, but the first artist that made a real impact on me was probably Picasso. I loved his inventiveness, what he could do with line, the way he’d make images which would then become other things and just the sheer output. More recently I’ve been looking at artists who belong to the early European avant-garde, like Sophie Taeuber-Arp, and Władysław Strzemiński. There are so many. Paul Klee is just so lyrical and then there’s people like Bart van der Leck and Josef Albers. I love the work of Carmen Herrera, Marcia Hafif and Fanny Sanín. Philip Guston has been a huge influence on my work. I draw from all of these artists but conceptually my thinking is informed by Peter Halley and David Diao - or artists like David Salle or Julia Wachtel and the way they cut and paste, mix and match.

JK It’s interesting that you bring up the Fayum portraits because, as I’m sure you’re aware, they were made to be buried with their subject and weren’t meant to be seen by anyone else. I couldn’t think of anything further from art about art, in that sense.

JB Yes, they are pre-Byzantine, it’s pre-Icon painting that makes everything symbolic. They’re not about individual expression by the artist. They precede that change in art. They’re also quite naturalistic.

JK The way the eyes are rendered is incredible.

JB Yes, and they functioned like passport photographs for the afterlife.

JK It’s fascinating to think about the motivations of an artist who would paint something like that. It’s probably something that we can’t even conceive of. Did your childhood in Caracas have an influence on your trajectory as an artist?

JB The short answer is yes but it’s difficult to know exactly what that influence was. More and more Venezuela is becoming like this memory. It’s kind of like Blade Runner, you know, did I actually live there? Also, there’s the fact that Venezuela was, at that time, informed by many things. For example, there was a strong Modernist influence in South America, particularly in Venezuela. At the university where my parents used to teach, the campus was full of artworks and murals. There was also this mix of television and music and logos, a lot of baseball - there was this strong American influence. I think that mixing of things has probably remained in me. Venezuela is a place that I’ve written about in short stories and I often try to recall my memories from there. I grew up in Caracas, which is the main city, but we also travelled a lot to Margarita, which is a small island where my father was born and it was a little bit like going back in time or walking into a Magic Realist novel. In some ways it was quite a harsh environment. Nature is very powerful in a place like Margarita. We’d have bats flying through the living room while my grandma is watching telenovellas. You know it was like a Garcia Marquez scene.

| BY JUAN BOLIVAR

One summer my father and I were driving cross-country to the east coast of Venezuela. We were heading to Cumana – a port from which we would board a ferry to Margarita – the island where my father was born. We left early before sunrise around 3:00 am. The old 'carretera’ de caracas, now replaced by a highway, meant exiting the city was no longer the treacherous journey through winding mountainous roads I remembered as a child. Even so the cross-country drive to Cumana would take approximately eight hours. The long road flanked either side by vegetation would occasionally become a flatland interrupted only by fading cigarette advertisements or Pepsi-Cola billboards, concrete and breezeblock restaurants and restrooms with hand painted signs the only other signs of life. As the sun rose, the radio would keep us company on a road trip without many stops or exits. For the journey my father would prepare camomile tea and cold chicken. The car had no air-conditioning; a white Mercedes-Benz (off-white to be precise) which my parents bought straight from the dealership in Germany in 1969 when the ‘Bolivar’ was strong. Now over twenty years old the cracked upholstery bore witness to its life in the tropics, but ‘El Mercedes’ was as reliable as you get and never broke-down in all its years of service. My father had a near mystical relationship with this car. It took us to remote parts of Venezuela, from the Caribbean, to the Andes, to the Medanos de Coro – a small desert in the west coast of Venezuela. We grew up in this car like an extended family home; driving to school, the ‘UCV' (the university where my parents taught), Judo lessons, bowling on the weekends, and drive-in cinema nights followed by visits to ‘Tropi Burger’. Over time my father developed a short-hand, sign-language to communicate through the car like morse code. A long ‘toot’ of the horn, followed by a short toot – repeated twice –announcing whenever he was near home; always at a steady pace no matter how keen he was to get back. My father was a good driver who kept to the speed limit other than when overtaking vehicles. The journey to Cumana was steady except for delays when encountering large trucks known in Venezuela as 'gandolas' – a word originating in the 1950s when Italian construction workers building roads in venezuela would refer to the trucks and transportation vehicles they had brought to the country as gondolas; a term that would later become assimilated as ‘gandolas'. Overtaking a gandola was a skilled art on a one-lane road, with oncoming traffic restricting opportunities. Skilfully timing these moments, my father would accelerate, calculating with precision the opportune moment for overtaking. The intense heat on the tarmac would occasionally create a mirage illusion of water appearing in the distance as vehicles approached. It was around 8.00am, roughly halfway on our journey, when a large leaf fell from a tree in front of us. The tree in question was not of a North American variety where leaves would at most be the size of an outstretched hand, but this leaf fell from a tropical tree variety resembling a palm tree normally found on a beach. Green-brown leaves extending onto the road, we noticed one falling slowly, so large that at first, we believed this to be an animal like a 'pereza' (sloth). My father slammed the breaks, slowing down; eventually driving over what we could now see was a leaf. Picking up speed again we saw a gandola in the distance. As it neared my father began to time his moment to overtake, when 30-40 metres away the gandola's back doors swung open revealing what can only be described as a giant tyre; two metres tall, staring at us like a raging bull about to be released. From this point time moved very quickly but very slowly, like in a movie; the left back door now fully opened outstretched onto the road as the tyre began to roll forward, leaping out of the back of the truck – hitting the ground and bouncing hard like a rubber ball from a game of ‘jacks’. The giant tyre may have bounced directly in front of us, or perhaps after a second bounce leapt over. Either way, the tyre taller than a car, bounced inches away from our bonnet as we saw this fly above us, land behind and roll into the distance. My father and I looked at each other in disbelief and without words, but with the suspicion that somehow the fortuitous falling leaf may have instigated an alternative sequence of events. Later that evening we related the story to my mother. She exclaimed how at that time in the morning she’d suddenly woken up shouting "Yaya protect them". Yaya: my mother's mother, who appeared to her in a dream on this day the anniversary of her death. During this period in the early 1990s I made paintings in a gestural manner depicting floating orbs one could loosely describe as planets. The planets became structures resembling colourful scaffoldings; later reducing my palette and motifs further still into hard-edge compositions. I spent the next years until the mid-90s making a series of paintings where the letter E was repeated in five colours set within a white boarder. By the late 90s other configurations had appeared gradually becoming colour-fields. The colourfields were empty and void of form until the millennium when circles reappeared, not as planets but globes set within facialities; like eyes looking at the viewer.