54 minute read

DESIGN

JH Living DESIGN

Continuum

Advertisement

A new hotel in Teton Village isn’t designed to be just a place to stay, but also to provide guests a chance to experience a very Jackson Hole lifestyle.

BY SAMANTHA SIMMA

BEHEMOTH BLACK DOORS greet guests at Teton Village’s newest property, Continuum—not just a hotel, but, as its website declares, also a “Teton Gravity Research experience.” Here you can relax and sleep in one of eightythree modern rooms; ogle photos of professional action-sports stars who have appeared in movies Teton Gravity Research (TGR) has produced; and maybe even mingle with some of these athletes in the hotel’s bar. “A lot of hotels are very one dimensional,” says TGR cofounder Steve Jones. “You go in, check into your hotel room.” And that’s it. Jones felt that making TGR a part of the hotel experience could be really special, particularly if the hotel was at the base of TGR’s home ski resort.

Rooms at Continuum were designed by Los Angeles-based boutique design firm Powerstrip Studio to have a unique, modern aesthetic.

If you’re unfamiliar with TGR, here’s a brief history: From a dingy Teton Village office space, the company—initially brothers Steve and Todd Jones along with three friends—reinvented the genre of ski films in the mid and late ’90s, showcasing skiers hitting big backcountry lines instead of shooting tight shots of crisp turns on groomers. Since then, TGR has grown into an action-sportsmedia juggernaut and accompanying lifestyle brand that has produced more than 40 movies; numerous original television series; and commercials for companies including Apple, The North Face, Jeep, Under Armour, and Energizer; and launched a clothing line. For years, TGR used a hotel near its offices, The Inn at Jackson Hole, as a basecamp for its athletes, sponsors, and friends; and as a place to unwind after a day of hard skiing. The Inn was one of the first hotels built at the base area of the nascent Jackson Hole ski area. It opened in 1968, three years after the resort’s tram started carrying expert skiers from around the world to the summit of Rendezvous Mountain. “You could say The Inn has always been TGR’s clubhouse,” Jones says, recalling après-ski sessions at The Inn’s Beaver Dick’s Bar.

Despite TGR using the property for its athletes and friends, by the late ’00s, The Inn was financially struggling and in mild disrepair—a condition highlighted as hotels like the Four Seasons and the country’s first LEED-Gold–certified boutique hotel, Hotel Terra, opened around it. In 2010, while in Jackson Hole on a ski vacation, David and Ellie Gibson heard The Inn was for sale. The couple bought it. Initially they didn’t plan on partnering with TGR or even knew this was something in which the brand was interested. And, while they knew the building needed serious help, they weren’t sure whether it was a remodel or a rebuild. After thinking about it for a while, they came up with a hybrid option: renovate and remodel the guest rooms and build a new lobby and central public spaces.

AVID TRAVELERS, THE Gibsons had ideas for the aesthetic they wanted their property to have. “We knew we did not want ‘mountain west,’” Ellie says. Instead, they sought a departure from Jackson’s go-to palette of browns, oranges, and

Continuum’s restaurant, lobby, and bar.

—STEVE JONES, TGR COFOUNDER

plaids. “I don’t want to walk into a space and feel like I’ve already been there before because I’ve seen it everywhere else,” Ellie says. After seeing the 39 Degrees restaurant in the Sky Hotel in Aspen (which has since been redeveloped into a W Hotel), they hired the Los Angeles–based boutique design firm Powerstrip Studio to bring their vision to fruition.

It was during the design-and-construction process that the Gibsons heard TGR wanted to bring its brand to a Teton Village property. Steve Jones envisioned a place where guests would be able to interact with TGR athletes and a central location for sports clinics with the personality to make guests feel like they were TGR-film bound. “A modern-day version of our clubhouse with better food, drinks, and a big pool to après-ski in—this was a very natural extension for the TGR brand,” Jones says.

The partnership was a no-brainer for the Gibsons; they recognized the local, national, and international audience TGR would bring. Deciding on a name was a fairly easy decision too: TGR’s first film (released in 1996) was The Continuum. David, who first visited the area as a teenager, says the name “illustrates the clean elegance and sophistication of our target experience.” To bring the branding and name full circle, Powerstrip’s design concept sought to appeal to “the guest who pursues athletic adventure, [and] has an appreciation for style,” says studio co-founder Dayna Lee.

THERE’S NO DOUBT Continuum melds athleticism, style, and aspiration. “We sought to create a clean setting that would appeal to adventuristic destination travelers,” Ellie says. “I like very clean spaces. I don’t like to walk into a room and there’s so much pattern going on and so many different things that you don’t know where your eyes should go— they’re just jumping around.” The range of color in Continuum is minimal— white and black, punctuated by the occasional pop of color, like a deep-green chair in an upstairs public space.

But for all its high style, the hotel is undoubtedly TGR. In the lobby, guests can don virtual reality goggles to get into a helicopter with skier Angel Collinson or catch a big wave with surfer Rob Machado, both of whom have appeared in multiple TGR films. TGR movies play continuously on a wall of TVs behind the bar in the hotel’s ground-floor restaurant. Sometimes the hotel hosts premieres of new TGR efforts. The bar spills out to a patio with a 25-person hot tub. Jones says creating energizing, active social spaces like these goes with TGR’s approach to the outdoors and culture of having fun. JH

BLUE MOOSE LODGE

Peak Properties

THE FACTOR THAT makes the Jackson Hole real estate market so unusual is the relative scarcity of private land. Ninety-seven percent of Teton County, Wyoming, is publicly owned—either national park, national forest, or wildlife refuge. This computes to just 75,000 privately held acres in a county spanning 2.5 million acres. The guaranteed open spaces and unobstructed views these surrounding public lands afford make the remaining private land a real treasure. Add the abundance of recreational opportunities found in and around the valley, and the quality of life one can enjoy in Jackson Hole is simply unbeatable.

Moreover, many of the properties featured here are secluded, scenic retreats located in the midst of prime wildlife habitat. Most existing and prospective property owners in Jackson Hole cherish this notion, and serve—or will serve—as stewards of nature.

One cannot put a dollar value on waking to the Teton skyline, skiing home for lunch, or listening to a trout stream gurgling through the backyard. In Jackson Hole, “living with nature” is not a fleeting, vicarious experience a person has while watching TV. Here it’s a fact of life, and we wouldn’t have it any other way.

HECK-OF-A-HILL HOME

4,588 square feet

6 bedrooms

6.5 baths

6,495,000 dollars

The Blue Moose Lodge is a private, stunning home in Teton Village. It has a chef’s kitchen with professional grade appliances, four master suites, a bunk room, a media room, a game room, fireplaces, large deck and hot tub. Designed by Dubbe Moulder Architects with interiors and furnishings by Louis Shanks. Every detail of this Teton Village residence embraces privacy with its setting in the native forest and neighboring ski hills.

Berkshire Hathaway HomeServices Brokers of Jackson Hole Real Estate Sally Yocum - (307) 690-6808 sally@bhhsjacksonhole.com bhhsjacksonhole.com

2,781 square feet

4 bedrooms

2 baths

7,950,000 dollars

Located 1 mile from Wilson sits a 12-acre private retreat. Perched above the valley, the open-concept home encompasses wide sweeping views through large picture windows of mountain ranges, including Sleeping Indian and the Grand Teton. The original horse barn was carefully renovated and reimagined to create a spa bathroom, soapstone shower, full kitchen with large entertaining areas inside and outside. Aspen groves, conifers and wildflowers flourish on this amazingly private property.

Berkshire Hathaway HomeServices Brokers of Jackson Hole Real Estate Nick Houfek - (307) 399-7115 • Andrew Byron - (308) 690-2767 nick@bhhsjacksonhole.com • andrew@bhhsjacksonhole.com bhhsjacksonhole.com

5,351 square feet

5 bedrooms

6 baths

4,600,000 dollars

20-3027 MLS#

Enjoy the sunlit radiance of the Grand Tetons & Sleeping Indian from the comfort of this nearly new residence. Wonderfully sited and elegantly appointed with high ceilings and huge windows to take in the natural beauty of Jackson Hole. Attention to detail was not overlooked including a chef’s entertaining kitchen, multiple living spaces, gracious foyer, top of the line appliances, exquisite lighting, beautifully landscaped, plus a 1-bedroom guest house.

Budge Realty Group Jackson Hole Real Estate Associates (307) 413-1362

THE GLENWOOD

— square feet

2 + LOFT bedrooms

2 baths

849,500 dollars

20-378 MLS#

Step into this bright and cheerful townhome, 2 BR, 2B plus loft, attached garage and large south facing deck. Conveniently located just minutes from town and on a quiet street in Rafter J Ranch. A short distance from shopping, schools and daily activities

Jackson Hole Real Estate Associates Nancy Martino (307) 690-1022 nancymartino@jhrea.com

VOGEL HILL - RANCH 3

3,165 square feet

3 bedrooms

3.5 baths

3,890,000 dollars

Flawlessness is a rare commodity in the modern world, but you recognize it when you see it. That’s exactly what we have created at The Glenwood, an intimate community of 3-story luxury townhomes at the center of downtown Jackson. It is a property built on the idea that “good enough” simply never is. Designed for discerning people who know excellence is in every detail, it’s the new standard-bearer for luxury mountain living. One of seventeen units available.

Jackson Hole Sotheby’s International Realty Bill Van Gelder - (307) 690-0178 bill.vangelder@jhsir.com theglenwoodjh.com

35.2 acres

— bedrooms

— baths

7,500,000 dollars

Ranch No. 3 sits atop 35.2 acres of sprawling aspen and pine tree groves, endearing it as one of Vogel Hill’s more private ranches. On the northern side, this site accesses 117 open acres of protected wildlife & trails. Lush sage and native grasses lead to an open homesite with full Grand Teton views and spectacular views up the Spring Gulch corridor into Grand Teton National Park.

Jackson Hole Sotheby’s International Realty Brandon Spackman - (307) 690-8156 brandon.spackman@jhsir.com spackmansinjacksonhole.com

2,374 square feet

3 bedrooms

3 baths

1,695,000 dollars

— MLS#

Enjoy the convenience of town living in this charming 3 bedroom Wilson Bungalow located steps to town amenities, the bike path and Wilson Elementary School. Large south and west facing windows offer incredible views of Glory Bowl, the Wilson Faces and the Historic Hardeman Barn. An inverted floor plan places the living and dining areas on the second floor, providing great light and views. The two main floor guest bedrooms are suited and the home has an attached two bay garage.

Jackson Hole Sotheby’s International Realty Jennifer Dawes jenn.dawes@jhsir.com

A PRIVATE PARADISE ON 34 ACRES

22 acres

— bedrooms

— baths

— dollars

— MLS#

Beautiful acreage tucked up against the foothills in the south end of Teton Valley. Conveniently located minutes from incredible mountain biking and trail riding, Teton Springs Golf Resort and Teton Pass to Jackson Hole Mountain Resort and the historic town of Jackson Hole. Zoned AG 2.5, this property can easily be subdivided through the County’s Subdivision process. The property has 20 shares of trail creek water rights and no CC&Rs or restrictions, allowing a Buyer much flexibility.

Jackson Hole Sotheby’s International Realty Jennifer Dawes jenn.dawes@jhsir.com

WILSON BUILDING LOT-SUNSHINE & VIEWS

11,815 square feet

8 bedrooms

12 baths

15,000,000 dollars

Singing Trees is a 33.76 acre property nestled among mature conifers and aspen trees, on a lake complete with a sandy beach just 20 minutes from the town of Jackson. The property is subdivided into four parcels giving it potential for a family compound or conservation easements. It has breathtaking views of the Grand Tetons and the surrounding countryside which is bordered on the west by the national forest, providing private access to excellent horseback riding and hiking.

Jackson Hole Sotheby’s International Realty Huff Vaughn Sassi (307) 203-3000 huffvaughnsassi@jhsir.com mercedeshuff.com

4 acres

— bedrooms

— baths

648,500 dollars

This lovely building site is one of the few in Indian Paintbrush that has exceptional sunshine with south-east views. There are beautiful stands of aspens and gigantic pines that tower over the property providing privacy without compromising sunny exposure. Lot has a flatter building site with sloping southern perimeter and surprising Sleeping Indian views. Architectural renderings available. Very close to National Forest access for cross country skiing, biking, hiking and horseback riding.

Jackson Hole Sotheby’s International Realty Pamela Renner - (307) 690-5530 pamela.renner@jhsir.com

2,416 square feet

3 bedrooms

3.5 baths

2,750,000 dollars

20-226 MLS#

Highly desirable ski-in ski-out Moose Creek townhome offers a convenient location, privacy and mountain views. Located at the base of the Jackson Hole Mountain Resort directly across the street from the Moose Creek chairlift and just minutes from the many amenities of Teton Village. This townhome sleeps 8 comfortably in the 3 spacious bedrooms with en-suite bathrooms plus an overflow bunk room and private hot tub to enjoy after a day on the mountain. Wellappointed and offered fully furnished. Strong rental history.

Spackmans & Associates (307) 690-8156 spackmans@jhsir.com

TETON RANGE RANCH IN DRIGGS, IDAHO

65 acres

5 bedrooms

Located minutes from downtown Jackson, Cody Creek Sanctuary is a 65-acre private refuge featuring a classic log home, remarkable open spaces, invaluable wildlife habitat and expansive waterscapes teeming with cutthroat. Learn more, CodyCreekJacksonHole.com

6 baths

18,900,000 dollars

20-1683 MLS# Live Water Properties Jackson Hole Latham Jenkins - (307) 690-1642 latham@livewaterproperties.com LivewaterJacksonHole.com

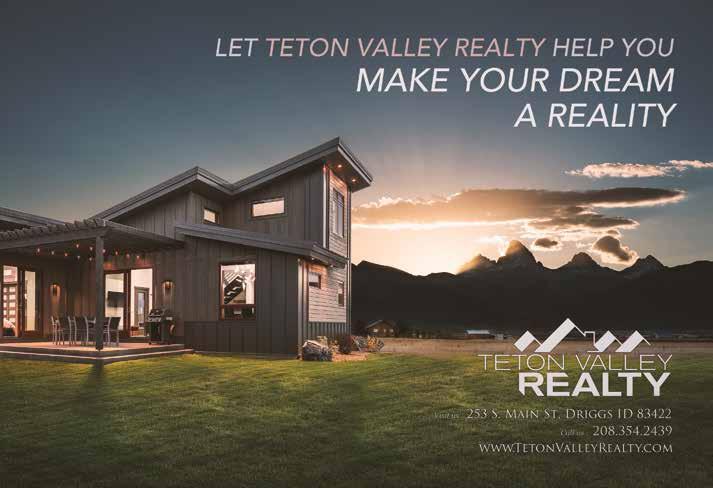

TETON RANGE RANCH IN DRIGGS, IDAHO

240 acres

— bedrooms

— baths

$835,000 dollars

Stunning property in the heart of Teton Valley! This 240 acre parcel offers an excellent location with County road on two sides (South and West). This flat acreage affords an owner the opportunity to create home site(s) with stunning Teton and Valley views, while maintaining the agricultural charm and feel of the area. This large parcel could be the perfect opportunity for a conservation easement, or farm/ranch with easy access, water rights and gorgeous views.

Teton Valley Realty Mandy Rockefeller - (208) 313-3621 mandy@tetonvalleyrealty.com tetonvalleyrealty.com

160 acres

— bedrooms

— baths

$800,000 dollars

Teton views & prime farmland! Build your dream home with plenty of room to farm or ranch on this scenic 160 acres of gorgeous, rolling ground with panoramic mountain views. Located just East of the Teton River, this parcel also boasts incredible views of the majestic Teton mountain range. With no restrictions, this blank canvas allows you to build and develop as you wish. The lush soils are currently planted in alfalfa.

Teton Valley Realty William Fay - (208) 351-4446 bill@tetonvalleyrealty.com tetonvalleyrealty.com

TEN 10 WAYS TO MAKE THIS YOUR BEST WINTER VACATION EVER

A decade ago, a winter vacation to Jackson Hole was a ski vacation. Nowadays, skiing is just one activity of many. We’re not saying you need to do all of these in order to have an amazing time here, just that, if you do, you’ll be gifting yourself the winter vacation of a lifetime. BY LILA EDYTHE

A winter vacation to Jackson Hole isn't complete without skiing at one of the three ski resorts in the area. Pictured here is Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, which is often rated as one of the best ski resorts in North America.

RYAN DORGAN

2SNOWSHOE IN GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK Usually, between mid-December and midMarch, Grand Teton National Park (GTNP) offers free two-hour ranger-led snowshoe hikes several times a week. These include the use of historic snowshoes, some of which date from the 1940s, and start from the Bradley-Taggart Lakes trailhead. Over the course of a mile, you’ll learn about local flora and fauna and get great Teton views. In pandemic times, GTNP isn’t sure if these hikes will happen, though. If they’re not an option this winter, (1) rent snowshoes from a local shop like Skinny Skis and explore the trails around Bradley and Taggart Lakes yourself, and (2) you’ve got a compelling reason for a return trip to the valley. nps. gov/grte/planyourvisit/rangerprograms.htm 1GET WILD WITH THE LOCALS It might be the National Elk Refuge, but the 24,700-acre refuge just north of town is home to more than 300 species of animals, including bison, osprey, wolves, sage-grouse, mountain lions, bald eagles, and bighorn sheep. Bighorn sheep, which are actually related to goats, can best be seen in winter, when they migrate down to the refuge from the high alpine areas of the Gros Ventre Mountains. Your best chance to see them requires driving just a couple of miles up the Elk Refuge Road. About one-half mile past the Miller House, look for their stocky bodies and distinctive horns—both rams and ewes have horns, although it is only rams whose horns curl around their heads—on the eastern slopes of Miller Butte. The Elk Refuge encourages visitors to not stop and allow the sheep or other animals to lick vehicles; the practice could contribute to the spread of disease and the road salts can contain harmful chemicals. fws.gov/refuge/ national_elk_refuge/ WINTER VACATION MUST-DOS BRADLY J. BONER BRADLY J. BONER

PRICE CHAMBERS In 2012, the founder of an outdoor gear company partnered with a husband and wife, both of whom were former winter Olympians, to resurrect and revamp the historic Turpin Meadow Ranch. At the base of Togwotee Pass in the northernmost reaches of Jackson Hole, the ranch’s lodge and eight main cabins date from 1932. When the group bought the property, it had been neglected for several years. Winterizing the buildings—all of the cabins were lifted and put onto foundations and heating and gas-lit fireplaces were installed—and adding a modern bathroom to each one took nearly two years. The work and investment were worth it. Today the cabins are havens of hygge, with bright interiors and wool Pendleton blankets on the beds, and there are miles of groomed trails for Nordic skiing, fat biking, and snowmobiling right out the front door. 307/543-9147; turpinmeadowranch.com4 3Picking a favorite ski run is hard. Deciding on a favorite hot chocolate in Jackson Hole might be harder. But we think you’re up to the task. At CocoLove (55 N. Glenwood St.; 307/733-3253), choose from Mexican Hot Chocolate with roasted chilies and spices and Swiss-style hot chocolate made with dark chocolate. Sister cafes Persephone (145 E. Broadway Ave.; 307/200-6708) and Picnic (1110 Maple Way; 307/264-2956) serve a mix of dark chocolate, sugar, and cocoa powder melted in milk and topped by a homemade vanilla or peppermint marshmallow. Pearl Street Bagels (145 W. Pearl Ave., Jackson and 1230 Ida Dr., Wilson; 307/739-1218) takes hot chocolate to the next level with its chocolate steamer—Monin dark chocolate syrup mixed with steamed milk (whole, skim, oat, coconut, almond, or soy) and topped with its homemade whipped cream. WINTER VACATION MUST-DOS STAY IN A LOG CABIN HOT CHOCOLATE TASTE TEST RYAN DORGAN TEN 10 BEST

DAVID J SWIFT Is it just us or is it human nature to crave ooey, gooey desserts when the temperatures outside are anything but ooey and gooey? The chocolate souffle at Snake River Grill requires thinking ahead—order it when you order your entrées—but there’s really not much to think about. Just get it. There’s a reason it’s been on the menu for more than twenty years. 84 E. Broadway 6 SOAK IN HOT SPRINGS Fed by natural hot springs, the five pools at the newly reopened Astoria Hot Springs are rich with magnesium, free sulfur, calcium, potassium, sodium, chloride, and alkalinity, making a soak here the perfect way to recover from a long day of play. On the banks of the Snake River, Astoria was popular with locals and visitors from 1961 until it closed in 1998. This new-andimproved iteration of Astoria took more than six years of planning and eighteen months of construction, and eventually the pools will be just one part of a 100-acre park and riparian area. Fair warning: Due to Covid-19, access to the pools might be limited to locals and requires advance reservations. Check current restrictions before going. 25 Johnny Counts Rd.; astoriahotspringspark.org 5 INDULGE IN A DECADENT DESSERT BRADLY J. BONER Ave.; snakerivergrill.com

Building a snowman might be the classic winter activity, and Jackson has plenty of snowy public parks that would happily host your creation. (BYO snowman eyes, nose, and mouth.) Top park picks include Phil Baux Park at the base of Snow King, Mike Yokel Park in East Jackson, Owen Bircher Park in Wilson (all tetonparksandrec.org), and R Park (jhlandtrust.org/r-park/) near the intersection of Highway 22 and Teton Village Road. One warning: Our snow, because it has such a low moisture content and is more fluffy than sticky, sometimes requires advanced snowman-making skills. Waiting for a wetter storm—or opting to make snow angels if your snowman isn’t 8 7Jackson Hole Mountain Resort (JHMR, Teton Village; jacksonhole.com) has evolved from appealing mostly to extreme skiers with its steep runs and deep powder into a family-friendly resort that balances wild and mild. It’s still home to the Hobacks— quad-busting, 2,000-vertical-foot powder slopes— but now more lifts than not service intermediatefriendly areas. (And there are now half a dozen spas in the base area to help you recover if you get wilder than you want.) On the western side of the Tetons, Grand Targhee Resort (Alta; grandtarghee.com) has a throwback feel and often gets more snow than the eastern side of the range. It’s also home to the only cat-skiing operation in the state. And then there’s Snow King Mountain (Jackson; snowkingmountain.com), which, when it opened in 1939, was Wyoming’s first ski resort. Nowadays, it’s overshadowed by JHMR and the ’Ghee, but, in downtown Jackson and home to the Jackson Hole Ski & Snowboard Club, whose athletes train there most afternoons, it’s a favorite with locals. (If you hear someone talking about the “Town Hill,” they’re talking about the King.) It also has the area’s only night skiing. WINTER VACATION MUST-DOS TEN 10 BEST HIT THE SLOPES BUILD A SNOWMAN RYAN DORGAN COURTESY OF JHMR PRICE CHAMBERS sticking—is totally acceptable.

We’ve often heard visitors who have the good fortune to discover the Cache Creek area about a mile east of downtown Jackson say, “Anywhere else, this place would be a national park.” Or something like that. But this is Jackson Hole, already home to two national parks, so Cache Creek Canyon is part of the Bridger-Teton National Forest (with some areas further protected as the Gros Ventre Wilderness). While “only” national forest, Cache Creek Canyon is still a wonderfully magical place. The creek burbles along the bottom of the canyon with ice BE IN A SNOW GLOBE WINTER VACATION MUST-DOS 9REBECCA NOBLE 10 TEN 10 BEST forming along its edges. Because high canyon walls keep much of the area in the shade, snow crystals often float in the air. Trees wear delicate coats of hoarfrost. In winter, you can explore this via foot, cross-country skis, fat bike, snowshoes, or snowmobile. Teton County Parks & Recreation grooms three miles of a former mining road a couple of times a week for classic and skate skiing. (The first two miles of this trail get enough traffic that you can hike and run without snowshoes, too.) If that’s not enough activity options for you, the nonprofit group Friends of Pathways grooms twelve miles of singletrack trails for fat biking. tetoncountywy.gov/1353/Grooming-Report

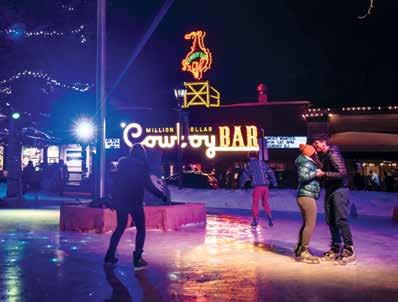

SKATE IN THE CENTER OF TOWN

Glide around our Town Square’s iconic elk antler arches beneath trees wrapped in white lights and in the glow of the Million Dollar Cowboy Bar’s vintage neon signs. The community-supported JH Winter Wonderland isn’t just an outdoor ice skating rink, but perhaps the cutest, coziest outdoor skating rink ever. gtsa.us/rink-on-the-town-square JH

Kate Wilmot, Grand Teton National Park bear-management specialist and Wildlife Brigade leader, monitors a bear jam in the northern region of the park. Wilmot says the Wildlife Brigade tries to let park visitors enjoy and experience wildlife as much as possible, and the group’s main purpose is to prevent potential conflicts.

TEXT MESSAGES FLEW, camera shutters clicked, and social media streamed with scenes of frolicking grizzly bear cubs—cubs who caused cars to be bumper to bumper for the better part of half a mile along Teton Park Road—both sides—on July 17. All the buzz: Two sow grizzlies, each with cubs, were in the same place at the same time. But these weren’t just any bears, so this wasn’t an ordinary wildlife jam. The spectaTo the delight of the starry-eyed throngs, the estranged mother and daughter grizzlies interacted. “They got close,” veteran wildlife lensman Tom Mangelsen said at the scene. BRADLY J. BONER cle near the Mount Moran turnout

was magnified because of the specific bears in sight: Grizzly 399, a twentyfour-year-old matriarch of Grand Teton National Park who has raised seventeen cubs over the past fourteen years, often within eyeshot of park roads; and Grizzly 610, one of 399’s grown daughters. Compounding the excitement over seeing these sows were the six cubs they had between them. Grizzly 399 had four little ones in tow, an extraordinary number of cubs for a grizzly of any age, and 610 had two cubs of her own. “Three ninety-nine circled around to get downwind of them, then she caught a scent and everything was cool.” While the ursine adults were nonchalant about their reunion, their cubs—aunts and uncles and nieces and nephews, to use human terms— were much more curious. Some of them even played. “Fun to watch,” said Rita Bayles, a naturalist and filmmaker who was leading a photography tour that day. In her SUV’s back seat was a group of Californians. They had come to Grand Teton National Park (GTNP) with one goal:

399 and her cubs have made appearances on 60 Minutes. Along with the Cheneys, Harrison Ford, and Kanye, they are as well known as any Wyoming residents.

to see its famous grizzly bears, animals like 399, 610, Blondie, Bruno, and the rest of the bunch.

The National Park Service (NPS) biologists charged with managing the same grizzly bears and the crowds they create hesitate to even utter those numbers and names. To Kate Wilmot, a park biologist and fixture keeping people at a safe distance at bear jams, Grizzly 399 is “sow with four cubs.” This resistance to highlighting specific animals is rooted in some of the foundational principles of wildlife management, like wildlife managers focusing on the population instead of individuals. Gus Smith, GTNP’s science and natural resource chief, explains the rationale. “If I were to be a perfect flat hat [NPS employee], I’d say we want people to be inspired by the wildlife. But I don’t think that the numbers, and this celebrity that we’re talking about, should matter,” he says.

Welcomed or not, the celebrity is real. Grizzly 399 and her kin have an on-the-ground fan club burning tire rubber and shoe leather from whenever the bears emerge from their dens in the spring (April or May) until they disappear again to hibernate through the winter. News of them has appeared in newspapers around the world. They’re the stars of books like Grizzlies of Pilgrim Creek, which features images by Mangelsen and words by Todd Wilkinson, and the recent children’s book simply titled Grizzly 399. Images of them hang in Images of Nature, the downtown-Jackson gallery Mangelsen founded in 1978. Facebook pages, Instagram accounts, hashtags, and bumper stickers exist in their names (numbers). They’ve made appearances on 60 Minutes. Along with the Cheneys, Harrison Ford, and Kanye, they are as well known as any Wyoming residents.

Mangelsen remembers the beginnings of the bears’ icon status. A turning point came in 2011, when both Grizzly 399 and Grizzly 610 came out of their dens with litters of cubs. “We counted 228 different news outlets that covered it,” Mangelsen says. “Jane Goodall called from London and said, ‘One of your bears is in the Sunday paper.’ We found a story from Turkey. That was the beginning of the real fame, I think.” Mangelsen says he never would have guessed that Grand Teton’s grizzlies would become so popular.

Grizzly 399 crosses a road in Grand Teton National Park with her cub of the year in May 2016. The bear, estimated to be twenty-four-years old in 2020, attained worldwide fame for raising her young near the national park's roads, in full view of adoring fans.

YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK senior wildlife biologist Doug Smith (no relation to GTNP’s Gus Smith) isn’t so surprised by recognizable megafauna’s fame. People relate to each other and tell their human histories through stories, he says. It comes naturally that our interpretation of the wild world is also told through stories. What is a key component to any story? The characters involved.

After a quarter century researching the world’s most famous wolves, he knows well that the “celebritization” of wildlife can be a conundrum for the agencies involved. “In short, the government hates the naming of things, but the public loves it,” he says. “These animals get a name, whether a number or a humanized name, and a story develops. So what do you do?” Part of the reason agencies are reluctant to embrace celebrity wildlife is because eventually the animals die, and oftentimes humankind is the cause of that death, be it a bullet or bumper. And this is a proven recipe for a blowup.

Outrage over the death of a famous, named animal can reach impressive proportions. Yellowstone’s Doug Smith cites Cecil, a 13-year-old Zimbabwean lion made famous by its Hwange National Park upbringing. When a trophy-hunting dentist from Minnesota struck and killed Cecil with an arrow outside the park five years ago, hell broke loose. Protesters gathered outside the dentist’s shuttered office, and the international media covered the Cecil saga for weeks. There have been similar responses in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. When the alpha female wolf from a Lamar Valley pack known by wolf watchers as 06 was legally shot and killed by a hunter east of Yellowstone—outside of the park—Doug Smith got numerous calls from people who told him he should be fired because he didn’t speak out on her behalf loudly enough. “I also got calls from government people—and I won’t say who, state or federal—saying, ‘You need to calm this down because the wolf lovers are going nuts and it’s on you because you inflamed it,’” he says. “And I didn’t do anything. She got shot, and my phone and my emails started going off the hook.” Jackson Hole resident Cindy Campbell is one of the people who’s quick to call wildlife professionals when she feels they misstep. One of Teton Park’s grizzly-watching devotees, she appreciates the insight famous bears provide into the everyday management of agencies like the Wyoming Game and Fish Department. “The ambassador bears, we see how they manage them every day because they’re in the public eye,” says Campbell, who isn’t especially fond of the “celebrity” tag. She doesn’t want her ambassadors treated differently, but rather wants to see more compassion brought into the science and decision-making relating to all bears in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. She wants to see bruins set up

Dozens of media outlets penned articles about the killing of Wolf 832F by a hunter outside of Yellowstone’s boundaries in 2013. The alpha female was a favorite among tourists and local wolf watchers.

Beth Bennett and Sue Ernisse comfort one another while processing the news in June 2016 that a cub of grizzly 399’s had been struck and killed by a motorist near Pilgrim Creek Road. Fans of the celebrity bruin erected a small roadside memorial at the site of the incident.

for success by the decisions of managers but worries that isn’t always happening, based on observations of grizzlies she does know. “In their worlds of bureaucracy, they follow the book,” Campbell says of the agencies. “And it’s time for some new chapters to get written in that book.”

In 2014, the spotlight was on Grizzly 760, a subadult bear born to Grizzly 610 (thus a secondgeneration descendent of Grizzly 399). Seven-sixty was relocated by the Wyoming Game and Fish Department twice because of habituated behavior; the second time it was hauled across the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem to near Clark, Wyoming. Shortly after its resettlement here, the young male grizzly pulled down from a tree a deer carcass that they know best. “This should never happen again, ever,” Boulder, Colorado, resident Richard Spratley said from the lakeshore. “Game and Fish can’t do

Nandia Black, of Kildeer, Illinois, tosses a stone into Jackson Lake in memory of Grizzly Bear 760 during a morning memorial for the bruin in May 2015 at Colter Bay. The bear, the offspring of Grizzly 610, had been euthanized by Wyoming Game and Fish officials the previous fall after it had multiple conflicts with humans.

BRADLY J. BONER

this, ever again. Not to a good bear like that. He

was as gentle a soul as you’d ever want to know.” Wyoming Game and Fish’s large carnivore chief, Dan Thompson, was on the receiving end of the fury at the time. Six years later, he explained that he values a lot of what famous grizzlies like 760 bring to the table. “These animals can generate further interest and awareness in wildlife and wildlife habitats, and provide a glimpse to general laypersons across the world into the importance of all wildlife,” Thompson says. Still, he says the concept of celebrity critters poses a proverbial doubleedged sword: When the most famed specimens are lionized, sometimes they become “untouchable”—deified—and can do no wrong in the eyes of some people. “It makes it difficult,” Thompson says. “We get beat up a lot because we talk more about animals on the population level, but that’s what we have to do. We’re not going to conserve all the grizzly bears in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem because of one or two bears.” Many— sometimes dozens—of grizzlies are trapped and euthanized every year, whether because they’re hooked on human food and highly habituated, deemed a danger to humans, or are chronically killing livestock (addressing this conflict is a story for another issue). But wildlife managers like Thompson have sometimes shown a willingness to treat the most famous animals differently. “We’re not stupid,” Thompson says. “We have to realize those [celebrity] bears’ importance.” In 2018, the Endangered Species Act protections had ended for the Yellowstone region’s grizzlies, and the state of Wyoming was pressing forward with the first grizzly bear hunt in nearly four de“We get beat up a lot because we talk more about animals on the population level, but that’s what we have to do. We’re not going cades. It was immensely divisive and fought over in courts. Game and Fish selected license to conserve all the grizzly bears in the Greater Yellowstone holders—Mangelsen, armed Ecosystem because of one or two bears.” with his camera, was among them—before a federal judge — WYOMING GAME AND FISH LARGE CARNIVORE CHIEF DAN THOMPSON stepped in at the eleventh hour and halted the hunt. Although had been hung too low by a hunter. This was yet the hunt would have allowed up to twenty-two grizanother instance of 760’s habituation—deemed zlies to be killed, steps were taken to safeguard the dangerous by Game and Fish—and so the grizzly likes of 399, whose home range was part of a nowas trapped and killed. Once the Jackson Hole hunting buffer area adjoining GTNP and bear-watching community caught word, outrage Yellowstone. “We devised a regulation that would and calls for an investigation into wrongdoing essentially not allow that particular animal to ever were swift. Campbell spearheaded a social media be harvested,” Thompson says. “We protected every movement and helped organize a memorial on the place she’s ever lived.” That concession did not plashores of Jackson Lake the following spring. The cate conservationists like Campbell, who wanted to gathering was a testimony to the intense passion see all grizzlies treated the same—whether they’re people can develop for wildlife, especially those in the public eye or not.

In 1999, a female mountain lion denned and reared her cubs on Miller Butte, on the National Elk Refuge. Their cave was visible, and people traveled here from around the world to see and photograph the family.

IT’S VISIBILITY—PROXIMITY to roads, primarily—that enables the fandom, stardom, and stories that lead to animals developing reputations and names. The dynamics don’t discriminate based on species. “It’s not just limited to the charismatic megafauna, but [with them] it’s a lot more polarized,” Thompson says. When a rarely seen animal, a mountain lion queen, denned and reared her cubs on the flank of the National Elk Refuge’s Miller Butte in 1999, crowds came and watched for months and a moniker resulted: Spirit. People used Spirit to spearhead activism; the roadside scene sparked the formation of the nonprofit Cougar Fund, which is still around two decades later advocating on behalf of mountain lions.

Closely observing the same animals week after week affects people. Oftentimes, it inspires them

THOMAS D. MANGELSEN

Spirit and her three cubs on Miller Butte.

and makes them want to protect what’s left of the wild. Being around wolves for forty-two years changed Doug Smith’s life (he worked with wolves in Minnesota and Michigan before coming to Yellowstone). “I’ve learned from wolves about how to live life better,” he says. “They’re great parents. They’re infinitely patient. They’re not worried about tomorrow. They live in the moment 100 percent. They could die the next day, and they’re totally fine with it.” In Smith’s view, the future of wildlife conservation and management will continue to be driven by populations, but he also sees merit in recognizing and researching individuals. “For each species it varies, but generally a minority of individuals contribute to the majority of the productivity,” he says. He cited swans and loons, species where roughly 40 percent of the adults are responsible for 80 percent of cygnets and chicks. “What is it about the individuals who do all the contributing that’s different?” he asks. “If you look at it that way, studying individuals becomes really, really important. So why wouldn’t we identify them?” Doug Smith doesn’t hesitate to say he’s become emotionally invested in individual animals, especially early in his career. Inevitably, he developed favorites, like Wolf 9, an import from Canada who was among the first batch of wolves reintroduced to

THOMAS D. MANGELSEN

Yellowstone in 1995. Smith spent time with her in the pen, followed her on horseback and from an airplane, and then one day she just disappeared, which wasn’t easy for him. Wolf 5 was another one; Smith watched her slowly decline due to old age. She began to lag behind her pack, and then one day she went missing. “I flew and flew and flew and flew, and could never get her collar signal,” he says. “And, you know, that one was tough.”

Thompson says he’d pity anyone who happened to accidentally strike and kill a widely cherished animal like Grizzly 399. “I truly believe you’d have to go into witness relocation,” he says. “I don’t know how you’d get out of that.” This past year, the famous grizzly clans of Grand Teton National Park dodged any high-profile deaths through mid-November, though the matriarch—399—and her cubs found themselves in an unprecedented and concerning situation. For much of the late fall, the family was outside of the national park and in the southern valley, where there are subdivisions and ranches. Here they accessed human-related foods: a beekeeper's honey, livestock feed, and compost. Eating human foods can spell doom for any bear; “a fed bear is a dead bear” is a saying among wildlife biologists and game managers. Once bears associate humans with food, they might spend more time in developed areas, which can lead to unwanted human/bear encounters. When this happens, hazing, relocating and euthanizing bears are all possible outcomes. The fate of grizzly 399 and her four cubs was unclear as this edition of Jackson Hole magazine was sent to the printer.

While they were up in the park, the celebrity grizzlies proved to be more popular than ever, at least anecdotally. Mangelsen says that he and friends at times this past summer counted 200 to 300 vehicles—which likely meant there were several times as many people—at the largest bear jams. These

scenes are crowded, chaotic, and a challenge for Wilmot and her team of bearbrigade volunteers to manage, and can be off-putting for people seeking intimate wildlife-watching experiences. At the same time, they’re an opportunity for scores of people to peep their first-ever wild grizzly. GTNP’s Gus Smith sees the wildlife jams as the perfect nexus of the National Park Service’s mission. “It’s protecting the resource for future generations while allowing people to have these amazing experiences,” he says. Mangelsen, who’s watched the crowds swell as the years have passed, says the celebrity grizzly’s growing popularity is a worthwhile tradeoff. “I wish I had the whole park to myself, like everybody else does,” he says. “But this does give a voice to these bears.”

Yellowstone’s Doug Smith understands where fellow wildlife scientists who’ve dug in their heels, refusing to embrace celebrity, are coming from. “A lot of respected colleagues say, ‘Don’t do this,’ because the public fusses about it and the public locks onto it, and it’s all about populations,” he says. “And that is true.” But he believes the celebrity status of wildlife in the ecosystem has helped the cause of conservation. Unlike GTNP staff’s more anonymous treatment of their numbered and recognizable grizzly bears, Yellowstone employees more readily share the research numbers of their wolves with the inquiring public. Former Yellowstone Wolf Project biologist Rick McIntyre, who remains a wolf-watching fixture in the park even though he retired in 2018, was famous for his skillful storytelling of wolves like Wolf 832F—known as 06 by the public. His tales, often told in human terms, inspired connections between people standing at spotting scopes and the named and numbered wolves running wild. “I think the ‘celebritization’ has helped,” Smith says. He explains that well-known individual animals are helping build champions of wildlife and wild places: “I’m not going to say I’m in favor of [celebrity wildlife], but nature needs help. Nature’s declining. We’ve got to connect people with nature, and that’s what the national parks are designed to do. How are we going to do that? You can’t speak in generalities. You’ve got to say, ‘This bear, this wolf, this bison, this elk.’ You need a story, and the naming gives you a story.” JH

Discover The Scandia Down Diff erence

HEIRLOOM QUALITY DOWN COMFORTERS & PILLOWS EUROPEAN BED & BATH LINENS

Scandia Home • 165 Center Street • Jackson,WY • 307.733.1038

ALSO VISIT US IN BEVERLY HILLS & PALO ALTO jacksonhole@scandiahome.com Follow us @scandiahome

PHOTOS AND TEXT BY RYAN DORGAN

From flood to fire to condemnation, the attempted erasure of Kelly has been the town’s one constant.

IN 1978, DUNCAN Morrow, a National Park Service (NPS) spokesman, told the Jackson Hole News that there were two things giving him headaches. The first was “inholders”—some 32,000 people who owned private real estate within the boundaries of America’s national parks. The second headache Morrow offered up without hesitation: “Kelly, Wyoming.” At that time, Morrow’s two pains went hand-in-hand; the unassuming community of about one hundred people on the Gros Ventre River on Jackson Hole’s eastern flank was the center of a nationwide battle between private landowners and a federal government’s land-acquisition program.

Kelly, as we know it today, was subdivided in 1937, ten years after a flood wiped out almost all of the community and thirteen years before Grand Teton National Park was expanded to encompass it. A massive landslide in 1925 created an earthen dam across the Gros Ventre River; in 1927 this dam failed and all but three of Kelly’s buildings—its school and the Episcopal church and its parsonage—were washed away. Six Kelly residents died in the flood.

Of the 181 lots plotted in 1937, seventy-six of them (about 42 percent) have been acquired by the NPS. These are now part of Grand Teton National Park (GTNP). For years (and to this day), the NPS bought inholdings in Kelly and in national parks across the country under a “willingseller/willing-buyer” arrangement, often offering a cash deal with a lifetime lease that allowed residents to remain in their homes until they died, after which their homes would be demolished and the lots left to return to a natural state. To this day, 2.6 million of the 85 million acres that fall within NPS boundaries remain privately owned, with 884.3 of those private acres in GTNP.

While the vast majority of Kelly’s inholders sold their homes to the NPS voluntarily, the pressure picked up in the mid-1970s. At that time, with land values continuing to rise, Congress allocated $450 million over three years to the NPS for the purpose of purchasing all inholdings across federal lands nationwide. A career real estate man named Robert Lunger was brought to GTNP to buy up inholdings on behalf of the NPS. “Willingseller/ willing-buyer” remained the park service’s public position, but two landowners in Kelly were told by Lunger that their land would be condemned under eminent domain after plans to build cabins on their properties were deemed incompatible with the park’s mission to preserve undeveloped lands within its boundaries. “It was all in a very threatening way,” said a resident who Lunger visited at work. “It wasn’t ‘We wish you wouldn’t do that.’”

By the end of the 1970s, public pressure and changing park service priorities eased the push to erase Kelly, and by 1984 a new GTNP land-acquisition plan moved Kelly to the bottom of its priority list, recommending deferring any further acquisition of private property in Kelly so long as land uses compatible with the Teton County Comprehensive Plan continued.

Today, Kelly remains a small community reflective of its past, a patchwork of attempted erasure locked in time. Million-dollar houses sit beside modest cabins and NPS-owned vacant lots, while dilapidated homes signed over to the NPS decades ago continue to fall into disrepair, waiting for just enough funding for the bulldozer to return them to the earth.

THE BONNEY HOUSE

Lorraine and Orrin Bonney spent many summers in this cabin, which they bought from Oscar Seaton. If you’ve spent any time up high in Wyoming’s mountains, chances are you’re familiar with the Bonneys. The couple met on a mountaintop in the early 1950s and spent most of the rest of their summers in the alpine, exploring and writing guidebooks so that others could share in their experiences. They eventually wrote nearly twenty guidebooks; their first was published in 1960, the exhaustive Guide to the Wyoming Mountains and Wilderness Areas. Because of their combined explorations in the Wind River mountains, Wyoming’s largest range, a pass between the Titcomb and Dunwoody valleys was named after the couple. In the Tetons, a pinnacle on the North Ridge of the Middle Teton also bears the Bonney name. Orrin was an attorney in Houston, Texas, but the family lived for their summers in Jackson Hole. Before buying this cabin, they stayed in a tipi near Jenny Lake. The Kelly cabin jokingly came to be known as “Fort Bonney.” In 1976, the Bonneys sold their “fort” to the National Park Service but took advantage of the NPS’s policy allowing former owners of inholdings to live in their homes until their death. Orrin died in 1979, and Lorraine lived and climbed for another thirty-seven years, dying in 2016 at the age of ninety-three. (She lived in this cabin until at least 2012.) In 2019, the two were inducted into the Wyoming Outdoor Hall of Fame.

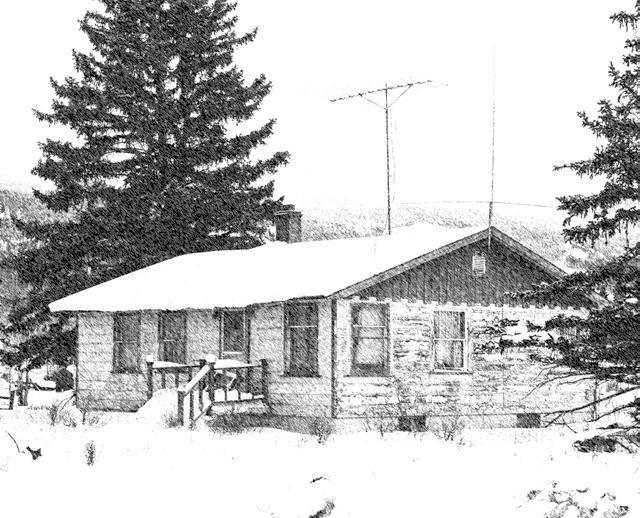

THE DRISKELL HOUSE

Dean and Iris (Carlson) Driskell bought this place from Iris’s parents. Dean was a contractor and had a cinder block shop on the property that’s still standing. In 1946, he and his nephew Glen “Bob” Wiley built one of Jackson’s first motels, the D&W, which eventually became the El Rancho Motel and is now part of the Anvil Hotel. In 1948, the men built research facilities in Moran for the Jackson Hole Wildlife Park, which today is part of Grand Teton National Park. To keep busy in the winter, Dean and Bob built snow planes in a cabinet shop in Jackson. This shop still stands; it’s the long building behind the former Jackson Hole Historical Society cabin at the intersection of Mercill and Glenwood Streets in downtown. The Driskells sold their Kelly home to the National Park Service (NPS) in 1984 but lived in it until 2003, when Dean died. (Iris died in 2010.) A neighbor said the house is now boarded up because kids broke in and started a fire on the living room floor one night after the Driskells had sold and moved out.

In 1927, World War I vet David “Tex” Little cut off the back of his Buick, turned it into a camper, and traveled the country. In 1943, he and his wife, Blanche, landed in Kelly. At that time, there were just a handful of other people living there, although the town of Jackson had a population of about 800. The flood that wiped out most of Kelly had happened sixteen years before the Littles’ arrival, but Tex and Blanche were among the first people to build a new home there. They raised two kids in this home. Neighbors say the road that connects Main Street to the Kelly School is not named Little School Road because of Kelly’s “little school” but because Tex Little put the road in. Tex ran an outfitting business out of this property and had a hunting camp up Arizona Creek, near the northern part of Jackson Lake. Neighbors tell of watching Tex dress moose that were hanging from the water tower behind his house. In the summers, Tex and Boots Allen guided fishermen on the Snake River. In a December 2000 issue of the Jackson Hole Guide, Suburban Propane ran a quarter-page ad wishing Tex a happy birthday and recognizing him for forty-six years of continuous propane service to his home. The Littles signed their home over to the NPS in 1972, but Tex lived here until October 2001. (Blanche had died in 1986.) He was ninety-eight years old when he moved from this house to Jackson. Tex died in 2006 at the age of 103. At the time of his death, he was the oldest resident of Teton County.

THE LITTLE HOUSE

THE FULLERTON HOUSE

Little is known of Sue Fullerton, who signed this home over to the National Park Service in 1978. It is not known how long she lived in the house after this. Fullerton helped to develop the geographic information system (GIS) for Grand Teton National Park and was recognized in 1993 for her accomplishments in the GIS program. She was a docent at the National Museum of Wildlife Art and was involved in the Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance’s annual silent art and antique auction. JH

STuCK UP

Stickers offer a window into the Jackson Hole community and culture.

BY JH MAGAZINE STAFF // PHOTOGRAPHY BY BRADLY J. BONER

“I THINK ONCE someone puts a sticker somewhere, it is just an invitation to put more there,” says graphic designer Walt Gerald, whose stickers celebrating the Teton County Library can be found around the valley (one is shown above). The biggest sticker repository in the valley might be the grain silo at the Snake River Brewery. The brewery has had this silo, which holds 60,000 pounds of Idaho-grown grain and is refilled about once a month, for twenty-six years. But it wasn’t until twelve years ago, when it was moved from the back of the facility to its current location at the entrance to the Snake River Brewpub, that stickerers really noticed it. “People just started putting stickers on it, and we thought it was generally funny, so we never bothered to do anything about it,” says Luke Bauer, a former brewpub waiter and currently the brewing company’s sales and marketing director.

Darrell Miller, whose production company Storm Show Studios has produced twenty full-length feature ski films, says he has been making Storm Show stickers and also stickers with the names of each of the movies the studio has done, since he founded Storm Show in 1999. He says he remembers putting a Storm Show sticker on the electrical box near the Mangy Moose about fifteen years ago. “Back then there were only about ten stickers on it,” he says. “It’s funny to see how it’s been wallpapered over. Who knows how many layers the sticker I put there fifteen years ago is now under?”

So why the electrical box by the Mangy Moose and not the one on Cache Street in downtown Jackson? “Location is key,” Miller says. “If you’re trying to get your message or brand to a particular group like, say, tourists or skiers, that electrical box at the Moose is the place. Hundreds of people probably walk by it everyday.” Miller says the giant microwave panel on the bootpack up Mount Glory on Teton Pass would be another great spot to get the attention of skiers and snowboarders. “That’s a cool spot, but I don’t think I’ve ever stuck anything there,” he says.

LOCAL OUTDOOR-INDUSTRY VETERAN SAM PETRI IS NOT INVOLVED WITH STICKERS HIMSELF, BUT, HE SAYS, “I PROBABLY PAY ATTENTION TO THEM MORE THAN MOST PEOPLE. MY FAVORITES ARE THE ONES THAT ARE SIMPLY THE BLACK STICKERS WITH THE WHITE WRITING—THE HOMEMADE ONES WITH NO DESIGN AND A PHRASE THAT IS SOME SORT OF INSIDE JOKE.” JACKSON HOLE HAS NO SHORTAGE OF THESE TYPES OF STICKERS. HERE WE’VE DECIPHERED SOME OF THE ONES YOU MIGHT FIND OUT IN THE WILD.

HIS NAME IS ANGUS

During a run for the U.S. Senate in 2013, Liz Cheney, daughter of former Vice President Dick Cheney, fumed at the then-editor-in-chief of the Jackson Hole News&Guide, Angus Thuermer, after he reported in the newspaper that Cheney had paid a fine for purchasing a resident fishing license even though she didn’t meet its requirement of having lived in the state for at least a year. At a campaign event, Cheney singled out Thuermer—“His name is Angus,” she told the crowd—and accused him of bias.

NO ONE CARES THAT YOU TELE

Aimed at telemark skiers who talk too much about the fact that they are telemark skiers. Side Note: Shortly after this sticker appeared, a subsequent sticker surfaced bearing a full-body silhouette of Michael Jackson on telemark skis, one heel cocked upward in his famous Moonwalk pose, alongside the caption, “Michael Cares.”

CHENEY SKIS IN JEANS

This dates back to the early 2000s when Dick Cheney, a resident of Jackson Hole, was Vice President of the United States. “Skiing in jeans” is a derisive joke in the ski community—essentially people who don’t have a clue are said to ski in jeans, so the sticker was a political dig of sorts.

DICK STOUT GOT ME OFF

Stout is a long-time Jackson Hole criminal defense attorney who is known for representing clients charged with DUI.

BRO BRAH BLAH BLAH

A dig at the vernacular of ski bums.

ROB SUCKS

Sorry, we’ve got no idea who Rob is. “I’m not cool enough to know who Rob is,” Petri says. “I always see these and go, ‘Who’s Rob?’ I’d love to know, but it’s also fun not to.”

local sticker lingo

stickers as art

JACKSONITE JEN REDDY’S

stickers have their roots in her art. “Stickers are a way for me to put my artwork out there,” she says. “They are more accessible to more people than an original painting.” For example, the twenty-four-bythirty-six-inch watercolor she did of a skier straight-lining through powder on a sunny day and casting a prominent shadow can only be in one place. She liked this painting so much though, and thought that it would resonate with others, so she turned it into a two-by-twoinch sticker and handed it out to people in lift lines at Jackson Hole Mountain Resort. “Stickers give artists the ability to widely share their work,” she says. Walt Gerald, a freelance graphic designer whose “Came for the Mountains, Stayed for the Library” series of stickers that support the Teton County Library are ubiquitous around the valley, says that he has a whole box of stickers of his own design and by others that he has no plans to stick anywhere. “I keep them as these little pieces of art,” he says.

“It is a thrill to see my stickers out there,” says Reddy, who estimates she has done about forty sticker designs in the last several years and usually prints one hundred at a time. Look for her “Sisters of Shred,” shown on pg. 83, and “Give Warm Fuzzies” stickers. The ideas for both came to her while in a lift line. About the latter she says, “It’s a reminder we can all be warm and comforting to each other, kind of like your favorite beanie.” “Sisters of Shred” started off as a painting. “Then I thought it would be perfect on a water bottle or skis,” Reddy says.

Right: Stickers on the refrigerator at D.O.G. (a cafe in downtown Jackson) Below: A sign at the top of Teton Pass.

If you think the Snake River Brewery’s grain silo has an impressive amount of stickers, know that there is actually a Guinness World Record for the world’s largest sticker ball. The current holder of this title is a ball of more than 200,000 stickers that weighs more than 230 pounds and lives in Longmont, Colorado. Created to coincide with the first-ever National Sticker Day, the ball was started by the StickerGiant labels company and was originally named Sticker Giant, SG for short. Recognizing that such a superlative sticker ball deserved a more imaginative name, the company renamed it Saul after the Saul Goodman character—initials were SG—in the AMC show Breaking Bad. If you’re around Longmont, you can arrange to visit StickerGiant’s world headquarters; Saul lives in the lobby and visitors are encouraged to add stickers to it.

“There are some very specific stickers that were made by brewpub regulars that are of some inside joke for the staff or locals, but by and large it’s just a phenomenon that’s fed on itself. People see stickers and they want to add their own,” says Snake River Brewery’s Luke Bauer, who estimates there are now thousands of stickers on the brewery's silo (shown to the left) and, in some places, the stickers are up to five layers thick.