9 minute read

PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT

Unhappy To Be Successful

If you make happiness your primary goal, you might miss out on success as well as the challenges that give life meaning.

Advertisement

In 2007, a group of researchers began testing a concept that seems, at first blush, as if it would never need testing: whether more happiness is always better than less. The researchers asked college students to rate their feelings on a scale from “unhappy” to “very happy” and compared the results with academic (GPA, missed classes) and social (number of close friends, time spent dating) outcomes. Though the “very happy” participants had the best social lives, they performed worse in school than those who were merely “happy.”

The researchers then examined a data set from another study that rated incoming college freshmen’s “cheerfulness” and tracked their income nearly two decades later. They found that the most cheerful in 1976 were not the highest earners in 1995; that distinction once again went to the second-highest group, which rated their cheerfulness as “above average” but not in the highest 10 percent.

As with everything in life, happiness has its trade-offs. Pursuing happiness to the exclusion of other goals–known as psychological hedonism–is not only an exercise in futility. It may also give you a life that you find you don’t want, one in which you don’t reach your full potential, you’re reluctant to take risks, and you choose fleeting pleasures over challenging experiences that give life meaning.

The way to understand the study above is not to deny that happiness is good; rather, it is to remember that a little bit of unhappiness has benefits. For instance, gloom has been found to aid in problemsolving. The author Emmy Gut argued in 1989 that some depressive symptoms can be a functional response to problems in the environment, leading us to pay appropriate attention and come up with solutions. In other words, when we are sad about something, we may be more likely to fix it. Psychologists call this the “analytical rumination hypothesis,” and it is supported by research. Obviously, this is not to argue that clinical depression is good — misery can quickly render people incapable of solving problems. Nor am I saying that depression passes a cost-benefit analysis. Rather, the analytical-rumination hypothesis is evidence that getting rid of bad feelings does not necessarily make us more effective in our tasks. And if these emotions can help us assess threats, it stands to reason that too much good feeling can lead us to disregard them. The literature on substance use suggests that this is so: In some people, very high degrees of positive emotion have been connected to dangerous behaviors such as alcohol and drug use and binge eating.

An aversion to unhappiness can lead us to forgo a meaningful life. Indeed, as one group of researchers that surveyed college students in 2018 found, fear of failure is positively correlated with meaning derived from romance, friendship, and (to a lesser extent) family. When I talk with people about their fear of negative outcomes in life, their true source of fear in many cases centers on how they will feel about having failed, not about the consequences of the failure itself. This is similar to the way discomfort with uncertainty causes more anxiety than guaranteed bad news. To avoid these bad feelings, people give up all kinds of opportunities that involve the possibility of failure.

But bringing good things into your life, whether love, career success, or something else, usually involves risk. Risk doesn’t necessarily make us happy, and a risky life is going to bring disappointment. But it can also bring bigger rewards than a life played safe, as the study of happiness, academic achievement, and income suggests. Those with the highest performance at work and school made decisions that were probably unpleasant at times, and even scary.

None of this is to say that we should shun good feelings, or that we’re foolish for wanting to be happy. On the contrary, the desire for happiness is natural and normal. However, making the quest for positive feelings—and the fight to banish negative ones—your highest or only goal is a costly life strategy. Unmitigated happiness is impossible to achieve (in this mortal coil at least), and chasing it can be dangerous and deleterious to our success. But more important, doing so sacrifices many of the elements of a good life. As Paul Bloom, a psychologist and the author of The Sweet Spot: The Pleasures of Suffering and the Search for Meaning, has written, “It is the suffering that we choose that affords the most opportunity for pleasure, meaning, and personal growth.”

Happiness itself would lose its meaning were it not for the contrast that we inevitably experience with sadness. “Even a happy life cannot be without a measure of darkness,” Carl Jung said in an interview in 1960. “The word ‘happy’ would lose its meaning if it were not balanced by sadness.” You can take Jung’s words to heart by committing to a regular practice of gratitude in which you give thanks not only for the things that make you happy but also for the ones that challenge you. It feels unnatural at first, but it will come easier each day.

Some of the most meaningful parts of our lives are a direct result of negative feelings that slipped through, despite our best efforts to block them out. For example, I am the father of three young adults; it was not long ago that my wife and I were going mano a mano with three teenagers. We lost a lot of sleep then, but I wouldn’t trade away a moment of those experiences (now that they are safely behind us). Some people take these lessons to lengths that might seem unimaginable. One is Andrew Solomon, the author of The Noonday Demon: An Atlas of Depression. “If one imagines a soul of iron that weathers with grief and rusts with mild depression, then major depression is the startling collapse of a whole structure,” he wrote. But as he told an interviewer several years ago, he eventually found a way to love his depression. “I love it because it has forced me to find and cling to joy,” he said.

This, in a nutshell, is the paradox of being fully alive. To strive for relentless positivity is to aim for the dimensionality of a Hollywood movie or children’s book. So though suffering should never be anyone’s goal, each of us can strive for a rich life in which we not only seek the sunshine but fully experience the rain that inevitably falls as well.

(By Arthur C. Brooks for The Atlantic Daily)

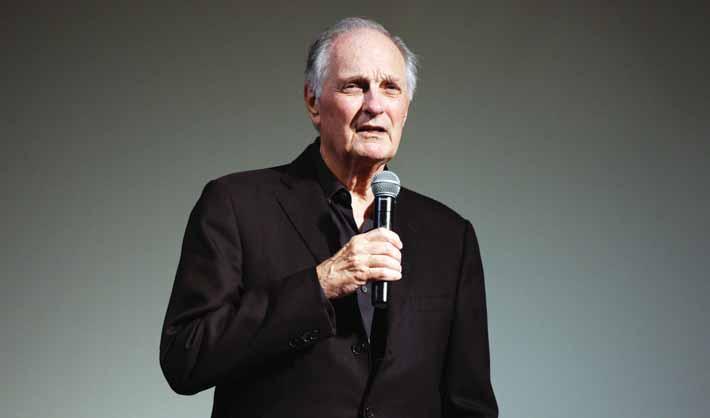

ACTOR AND SCIENCE COMMUNICATOR ALAN ALDA SHARES HIS THREE RULES OF THREE FOR EFFECTIVE AND EMPATHIC COMMUNICATION.

Whether you are a public speaker or having a heart-to-heart, it can be challenging to express your thoughts clearly. Alan Alda recommends making no more than three points, explaining difficult ideas in three ways, and repeating key points three times. However, these strategies will fall flat if not paired with an honest desire to connect with other people. Maybe this sounds familiar: You’re expressing a difficult idea, thought, or feeling, and at the moment, it seems to be going well. Your audience is nodding at the appropriate beats. Your cadence has an uncharacteristic flow and eloquence. You even snuck in the world profligate and are 90% sure you used it properly. (Well, 80% sure. Definitely going to look it up later.)

You take a deep breath, ask what everyone thinks, and realize that you’re getting the look. You know the one: mouths slightly agape, heads tilted in anticipation, and a squint like everyone just endured the world’s most strenuous eye exam. Everyone is more confused now than before you began talking. Whether from public speaking or just having a heart-to-heart, life is full of these types of conversations. You’ve been there, I’ve been there, and Alan Alda has been there.

Though best known for his role on the 1970s sitcom M*A*S*H, Alda is a public speaker, science enthusiast, and long-time advocate for better science communication. He has interviewed scientists as the host of Scientific

American Frontiers, won the AAAS Kavli Science Journalism Award, and founded the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science at Stony Brook University. In that time, he has developed a playbook of strategies to help people engage in conversation and voice their ideas clearly. If these tips can help biologists explain genetic drift, physicists Hawking radiation, or linguists anything about Chomskyan linguistics, then chances are they can help us express our thoughts and feelings when we need others to understand them the most.

1. Make no more than three points

1. Make no more points

1. Make no more than three points

1. Make no more than three points

1. Make no more points

The human brain can only store so much information in short-term memory. The oft-repeated number is seven items (or chunks). That number comes from research in the 1950s and has been reinforced in our collective subconscious by the fact that so many things happen in sevens. Consider that before the advent of cell phones, people spent lots of time memorizing seven-digit phone numbers.

However, follow-up research suggests that short-term memory is far less robust, maxing out at a meager three to five items.

If you’re old enough to recall memorizing phone numbers, you’ll recognize some truth in this. No one digested every digit at once. Instead, they broke the number into smaller chunks which they learned separately — most often, area code (three digits), prefix (three digits), and subscriber number (four digits). Only with time, repetition, and application would a number enter long-term memory as a single entry in someone’s mental Rolodex.

Short-term memory performs no better with ideas or thoughts than telephone numbers. It can only hold so many topics and tangents, and once it’s at capacity, it needs to erase old information to upload anything new.

Alda agrees. He advises you to limit your conversation points to no more than three, allowing you and your partner to focus on the thought at hand while avoiding disruptive additions.

2. EXPLAIN DIFFICULT IDEAS IN THREE DIFFERENT WAYS

As Alda said in his interview: “If I have a difficult thing to understand, if there’s something I think is not going to be that easy to get, I try to say it in three different ways. I think if you come in from different angles you have a better chance of getting a three-dimensional view of this difficult idea.”

One way to tap into this strategy is through metaphor. When Barbara Oakley was writing her book A Mind for Numbers, she reached out to professors who were highly ranked for their teaching skills. She discovered that across disciplines, the best professors were metaphor tacticians. They analogized key concepts or difficult ideas to better explain them.

According to Oakley, metaphors work by building on existing neural patterns established from previous learning. Those existing patterns then help create new neural networks for incorporating the new information. A physics teacher, for example, may explain the mindboggling concept of the expanding Universe by comparing it to how raisin bread expands as it bakes. Such a metaphor helps students connect the cosmologically large with something previously experienced on Earth.

This strategy doesn’t dumb down the concept but instead makes it relatable and therefore easier to understand — getting at that “three-dimensional view” Alda champions. Other useful strategies can include examples, visuals, changing the frame of reference, and providing a this-not-that comparison.

3. MAKE IMPORTANT POINTS THREE

Times

Repetition is a powerful communication tool because it helps us identify key information and transfer it from shortterm to long-term memory.

When it comes to learning, the best kind of repetition is spaced out. Whether you’re memorizing a phone number or a complex physics equation, revisiting and applying the information over several weeks cements it in your brain by developing and strengthening the neural patterns where the information is housed. This process explains why flashcards are such an effective studying tool.

In some close-knit relationships, spaced repetition is a phenomenal tool. Teachers, parents, psychiatrists, or team managers can use it to return to and reinforce difficult ideas across many conversations.

But time is more limited in other relationships. Even so, repetition is still a useful tool. Anytime you repeat something, it signals that this information is important, so pay attention. It’s why song, speech, and soliloquy writers use repetition so liberally. Think Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, the many soliloquies of Shakespeare, and, of course, Beyonce’s “Single Ladies.”

Express your thoughts clearly through connection

But Alda warns that tips only take you so far and may harm your efforts if you try to script your conversations like a formula to replicate someone else’s masterwork. Instead, Alda suggests that the true heart of communication is connection. Your goal shouldn’t be to enthrall your audience with a creative metaphor, meaningful pause, or witticism. That’s rhetoric, not communication.

“A tip is just an intellectualization of that, which might be okay to give somebody once they’ve got the grounding in the ability to connect, but it ought to come out of the connection. It shouldn’t be a checkbox that you tick off,” Alda said. Ultimately, we have to build a connection deep enough for communication strategies to work. These connections then help you understand when you need to slow down, repeat a key idea, or explain things from another angle.

(Credit: Big Think)

By Dr. Leif Hass