2 minute read

A BUS STOP IN NORTHERN IRELAND

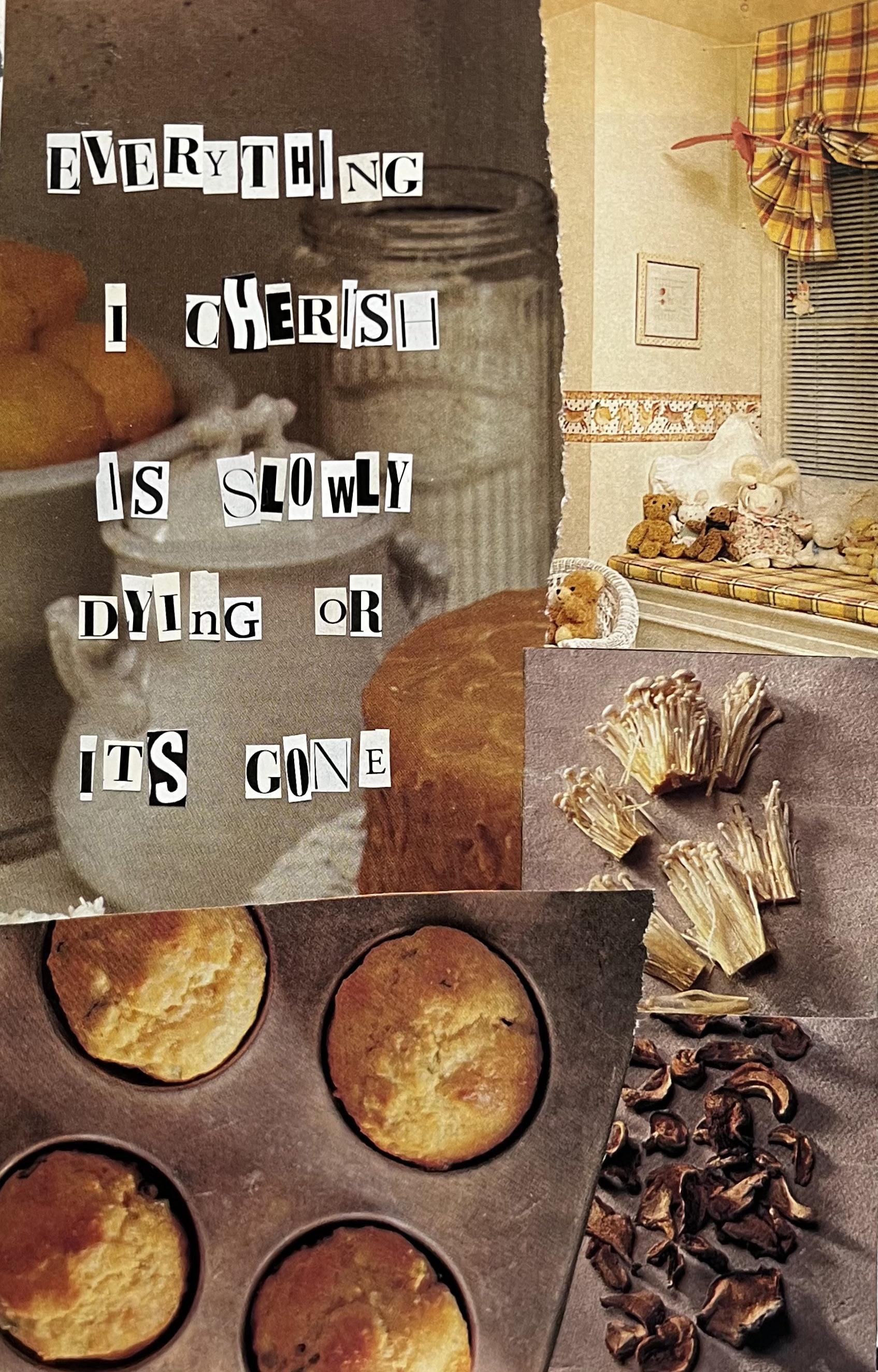

Time was an outlaw in the room, a fleeting, senseless thing that stuck to the radiator, which was probably why it never worked quite right.

The dark carpet was sacred ground, and to sleep was to waste the chance to explore its secret corners. My mother’s books hid in a cupboard with a creaking door. The stories of little girls, boxcar children, and puppies were tedious, But I liked to imagine that my mother mouthed the same words, her hands the last to cradle these spines.

I wanted to eat the strange titles and fonts.

It was not enough. My grandfather’s possessions rest in an unsteady pile across the room, a formidable dark shape in the night. They were a secret I did not know how to unravel. Not allowed. Untouchable.

It was inevitable that I would break that unspoken rule. I was old enough to know better, and young enough to taste blood in excitement.

I could feel that dark leather briefcase in my hands before I ever touched it, my desire was so thick.

I thought all that want was falling out of my mouth, but it was just the cold in that quiet purple room.

How disappointed I was to find nothing extraordinary but the sharp, careful handwriting of a man who died before I could ask him to please change these suffocating colors.

I blink and am back on the bus. I turn to look at my mother, who is looking out at the neighborhood.

She once said she would look out her window at night to see where smoke from bombings was rising, to choose the best bus route to take in the morning. Did she get up early today? Did she double-check the window before we went out?

The questions sit in my lap, the bus being stopped for too long now.

I want to ask the ugly things: if she agreed to marry my father because it meant leaving the room in the attic, what would we call my grandfather if he had lived to know us, why my granny has never once said I love you.

I want to ask if she ever grew used to the soldiers, the fear. I want to ask about the barely-mentioned gun barrels pointed at the back of her head when she walked into school.

I do not feel the need to look behind me, selfish in my safety.

We do not talk about the 3500 people who were left behind on these streets during these Troubled years, or what Uncle Allen did back then. I do not ask if this corner is one she ever walked by, if she knew people who used to live here.

I do not ask if she noticed that this place feels strange, like everyone is collectively holding their breath.

What I ask is if she knew this neighborhood, and she says, I didn’t go here, I didn’t want to get shot. I can feel the words bubbling in my mouth: Let’s go now, mom, let’s get off this bus, I’ll get off with you.

How can we remember what happened if we can’t leave?

I want to tuck my mother into bed. I want to tuck in every child that didn’t come home, all 186 of them, to tuck their fear into bed and then suffocate it. Kill it with comfort.

Love can only do so much. And mom, I am not strong enough to heave the lines under your eyes to bed, to make them rest, for you to close your eyes and feel safe.

I remember how carefully you heaved that ugly comforter over my shoulders last night, but I cannot open my mouth. I can still feel my grandfather’s leather case in my palms.