WANJU, WELCOME

The theme of this year’s National Reconciliation Week highlights the need for action, ‘now more than ever’. To transform reconciliation into action asks us all to reflect on how we can make a difference by redressing imbalances and advancing justice. We are extremely proud to present two powerful exhibitions that draw from histories where action was central – actions of force, of resistance, and of strength. In both exhibitions, these actions are reinterpreted, retold, and presented in contemporary ways in dynamic conversation with archival materials.

N’yettin-ngal Wagur – Yeye Wongie [Ancestors breath – Today talk] brings together four emerging Noongar artists who have responded to the artworks of the Carrolup Child Artists and the broader Carrolup story. Curtin, as the custodians of The Herbert Mayer Collection of Carrolup Artwork since 2013, has an obligation to share and better understand our history, and to continually explore ways to further truth-telling, healing, and reconciliation. Guided and led by emerging curator Zali Morgan (Whadjuk, Balladong, Wilman peoples), the artists in this exhibition, through research and visual explorations, have brought a contemporary reflection on that history. Through the lens of emerging Aboriginal artists who have engaged deeply with the artworks of the Carrolup children, this exhibition demonstrates a formidable continuum of artistic practice.

Also entwined in the confronting history of the 1905 Act, the context for The Strelley Mob is one of resistance and action. The Strelley Mob are descendants of the Pilbara pastoral workers who went on strike in 1946 and went on to run their own mines and stations. The recovery of the stories of the Strelley Mob from an archive of illustrated literature, produced by elders in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, has inspired the community to revisit

the history of the strike and the Strelley School, including in a new series of animations.

It is no accident that a university art gallery such as the John Curtin Gallery is hosting two exhibitions that centre on the strength of education. These exhibitions have been thoughtfully paired to amplify how knowledge systems can be transferred through learning. While the Carrolup artworks emerged from the disturbing truth of the Stolen Generations, there is an incredible strength made visible through the provision of materials and space for creativity. Similarly, the independence and power of the Strelley Mob is evident in the stories and illustrations that form the basis for this exhibition. Made by Nyangumarta people for their children when the Strelley Community School was opened, these artifacts demonstrate a remarkable self-determination and resistance.

The Gallery’s commitment to truth-telling through the Carrolup artworks will continue with the mid-year opening of a dedicated Carrolup gallery space at 139 St Georges Terrace – the Old Perth Boys School. Formerly a site for colonial education, this location will soon facilitate learning in a different way, commencing with Once Known, an exhibition that will encourage a deeper reflection of the past to enable truthful understandings of the present.

Central to all these exhibitions is the incredible yet simple power of the Carrolup and Strelley School drawings and illustrations. There is sense of careful observation of Country, of culture, of rituals and stories that are translated and interpreted visually to reveal part of our history in compelling ways. These artworks are a portal to examining our past and how it shapes our present, and for not just imagining our future but – now more than ever – spurring us to action.

A/Prof. Susanna Castleden Interim Director

N'YETTIN-NGAL WAGUR – YEYE WONGIE [ANCESTORS BREATH – TODAY TALK]

Power / Resistance: the Carrolup Child Art Movement and Noongar Art Today

Through their art practices, Amanda Bell, Brett Nannup, Lea Taylor, and Tyrown Waigana construct unique acts of resistance. Each artist holds space for past and future Noongar artists to coexist and collaborate, making their resistance sustainable and robust. They are ensuring Noongar art is true and sovereign.

N'yettin-ngal Wagur – Yeye Wongie allows the legacy and influence of the Carrolup Child Art Movement to be told through contemporary Noongar art. The truth of the Carrolup story continues in many ways today, with its artistic legacy shining through many Noongar artists – past, present and future. Each artist spent considerable time with the Carrolup works and ephemeral material. This allowed them to explore the critical themes that sit within and alongside the Carrolup Native Settlement, including the treatment of young Aboriginal people during colonisation.

Evolving from his mother’s long-standing practice, Brett Nannup continues to contribute to the legacy of Noongar printmaking whilst paying homage to the Carrolup boys, like Revel Cooper and Reynold Hart, who created designs intended to be made into glass plates. Brett has employed similar design elements and combines his own patterns and lines, highlighting Noongar marriage systems, shields, body paint designs, and his mother’s crochet rugs. Brett’s personal history holds a direct connection to Carrolup –his mother was born at Carrolup Native Settlement and later taken to Wandering Mission. Through his own family’s trauma, Brett’s prints seek to embody the pain and suffering endured by the Carrolup artists.

The Carrolup Native Settlement school ultimately became a place of resistance during Mr Noel White’s time, between 1946 and the school's closure in 1950. Mr White allowed the children to draw what they saw at the Settlement, creating what we know today as the works that form the Carrolup Child Art Movement. The Department of Native Affairs was opposed to Mr White’s practices with the imprisoned children, especially after their works were noticed at agricultural shows. They caught the eye of philanthropist Florence Rutter, which

meant the works would eventually be collected internationally. Mr White’s resistance to removing the children from culture ensured their legacy was not forgotten.

Amanda Bell unapologetically interrogates colonisation through her work. With delicate fabric and poetic lines, Warniny Ngaangk –Stitching My Mother, Stitching My Sun bleeds the untold stories of the girls at Carrolup. Often overlooked, the embroidery is essential in documenting their lives at the Settlement. The embroidery highlights the fauna and flora they were educated about, not necessarily the species surrounding the Settlement. With small stitches, each mark is made with the patience of a hurting child.

Although not forgotten, many of the children’s works are not attributed. This means the works were once known to the artist and their community, but they were not afforded care due to the children being Aboriginal and living on the Native Settlement. Tyrown Waigana explores the idea of the unknown artists through his series of digitally illustrated, faceless figures. Drawing on the materiality of the Carrolup drawings on paper, Tyrown has printed his illustrations onto a thin, poster-like paper. This reiterates the lack of care given to the children, while remembering that the drawings allowed a short period of hope for the children who were tragically severed from family and culture. The unknown artists’ works are uncomfortable and sad to engage with, and Tyrown emulates these feelings through his characters. Exploring the unknown works is a crucial part of the Carrolup history, as a story of Stolen Generations, and Tyrown’s large-scale illustrations encapsulate the yarn.

Dandeedeen wer Wilgi – Sew up and Paint, plays on ways that Aboriginal people have historically been represented as flora and fauna. By interpreting the handdrawn books by the children into a multi-panel work, Lea Taylor explores Noongar animals and plants endemic to Carrolup and around her home. Lea is a strong cultural leader, particularly through her work in public art and community workshops. Throughout Whadjuk Boodja, you find Lea’s work connecting back to Country and Community, ensuring our stories are told in accessible ways.

Accessibility to culture and story through art is integral for Aboriginal people. The children of Carrolup and similar institutions across Australia did not have access to their own culture under Government policies of forced assimilation. The Carrolup story and artwork must be accessible to community and family. It is vital that access is expanded beyond the walls of a gallery or storage facility.

Zali Morgan

The beginnings of this exhibition lie in several pivotal moments of the Pilbara’s history. One is the 1946 Pilbara Strike that took hundreds of Aboriginal workers off pastoral stations, to live collectively in camps that mined tin and other minerals, gather buffel grass and collect pearl shell. They lived independently for decades, battling the state government over their right to sell minerals. A second beginning lies in the Strike Mob’s purchase of Strelley Station in 1971, and the founding of Strelley Community School and the Strelley Literature Production Centre a handful of years later. Decades before this, the Literature Centre’s principal linguist Nyangumarta elder Monty Minyjun Hale gradually learnt to read English and in turn taught the linguists Geoff O’Grady and Ken Hale to become literate in Nyangumarta at the Strike camp near Roebourne. Monty’s daughters Barbara and Sharon, along with elder Bruce Thomas, are behind the adaptation of the Nyangumarta books for this exhibition.

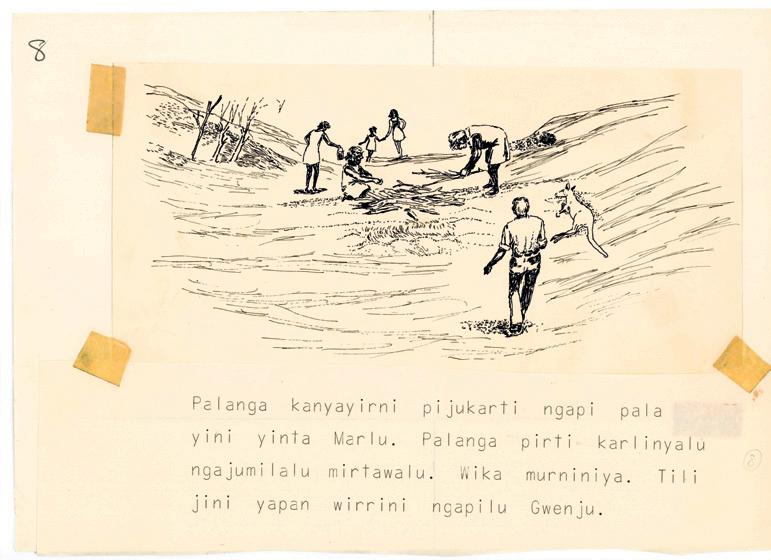

This exhibition is another kind of beginning for the Strelley Mob. It is the first time that a body of art and illustrated literature made by Nyangumarta people for Nyangumarta people has been shown to a wider audience. This is not Aboriginal art or literature produced for white, settler Australian collectors, gallery goers and readers. It is instead a cosmogonic body of stories and illustrations designed to keep Nyangumarta strong through reading, writing and speaking. One such story, Waraja marrngu kanya majalu (1982) tells of a pastoralist taking one of the strikers back to the station where he once worked, while Murtilyalujirri Nyungurrangu Yarnimarnapulujaninyi Panakatapa

Wirlarra, Yirntirri (1990) is about two men who create the stars, Moon and Milky Way. These are stories of life in the Pilbara, of the Dreaming, and the history of the Strike Mob.

Nyaparu (William) Gardiner, now a well known Australian artist, illustrated the very first Strelley book, Japartulupa pipilu ngaju kanyanyipulu kuyikarti, a story told by Monty’s daughter Sharon Hale in 1977. This is Gardiner’s earliest surviving illustration, and this and other stories are animated in this exhibition by Vladimir Todorovic and his team, while Annie Huang has developed a projection map of the Pilbara. This has been done under the supervision of Monty’s daughters Sharon and Barbara Hale, with the support and help of fellow Nyangumarta elder Bruce Thomas, and the counsel of Ingrid Walkley and Terry Butler-Blaxell of the Nomads Charitable & Educational Foundation.

The Nomads organisation supports the struggle of remote communities and schools to maintain a degree of independence from educational curriculums and other policies set by state governments. The Strelley Literature Production Centre was nested within the earliest of bilingual education programs that emerged in government and non-government Aboriginal schools during the late 1970s, 1980s and 1990s in Western Australia, the Northern Territory and South Australia. The distinct stories and lived experience that these books embody relays the subtleties, complexities of an Indigenous mother tongue and the relationship to the country from which the language emerges. We hope that in presenting these books, as a kind of Nyangumarta archive, vast in its breadth and vision, we impart a sense of how important the survival of first languages is for the heritage of Aboriginal Australia. We also hope that this exhibition illuminates the brilliance of its storytellers and storymakers.