13 minute read

Drag Racing

Don’t Wait Until You See the Green Light

Drag racing during the muscle car era

Advertisement

By MIKE MYER

I’d done my burnout and pulled up toward the staging light as the track announcer was informing spectators of my name, where I lived and that I was in the right lane. In the left lane, I could hear, was someone whose name sounded strange, from a small town with which I was acquainted. I glanced over.

Beside me was a fellow I knew, but not by the name that I’d heard. I knew why — he was a police chief, driving the town’s unmarked cruiser. You couldn’t tell it from any other car, until he placed the red light on the dashboard, flicked it on and came after you.

But there he and it were, and I was about to race them. He was slow on the starting lights.

I won, the only time in my life I’ve outrun a police chief in his cruiser — or tried to, for that matter.

We were at Eldora Dragstrip, just outside of Fairmont, in the midst of my short-lived drag racing career.

If you had a fast car — or even a slow one, in my case — the dragstrip was the place to be on a Saturday night. It was where you could find out just how fast your car — and you — were. It was the legal way to do that, at a time when virtually every community had places where informal drag races were staged illegally.

Drag racing is simple: Two cars line up, wait for the signal to go, then the drivers try to beat each other to the finish line, a quarter-mile away. That was then. Now, professional drag cars are so fast the distance is 1,000 feet, for safety purposes.

So much for simple. After humiliation in a few races, I learned there’s more to it.

Take the start: Between the two lanes at the starting line is a “Christmas tree,” so called because it has colored lights. At the top are two white ones, telling drivers when their front tires have broken a beam of line set (then) precisely 1,320 feet from another set of light beams at the end of the track.

Once both cars are staged, either an electronic timer or a human being triggers the countdown. For non-professional drivers like me, there were three to five yellow lights, timed to light up in sequence a half-second apart. Half a second after the last yellow light, the green light goes on and you launch.

Wait until you see the green light and, if you’re up against someone with any experience, you lose. Think about reaction time.

Smart drivers hit the gas when they see the last yellow light — or, in my case, between it and the

previous one. By the time you’ve reacted and your car is moving, you don’t leave the start line until green is showing.

Leave too soon and you “red light” — and lose automatically.

Slam your foot to the floor (or, with a manual transmission, do that at let the clutch pedal up suddenly), and you’ll probably lose. While you’re sitting at the start line, burning rubber, you can wave goodbye to your opponent as he or she feathers the gas just right to actually get moving faster.

There’s more to it than that, including a pre-staging burnout to warm the rear tires so they don’t spin a much, but you get the idea. Go to the track thinking you just let her rip and you’re going to lose.

I got reasonably good at it, with a shelf full of trophies to prove it. There was one thing I hadn’t accomplished, however: I hadn’t won a state championship.

So, one night in the early 1970s, I and the best drag racers in West Virginia were lined up at Eldora, racing for three-foot-high trophies. I got one by winning my class. That meant that, with appropriate handicaps at the starting lights to ensure the slower cars could compete against the faster ones, we class winners would race for “king of the hill.”

Somehow that night, I couldn’t lose. Up through the bracket I went until, to my astonishment, I was lined up for the final race.

A friend and his wife were in the stands with my better half, Connie. He told me later that as it became clear I was about to win the $500 prize money, he shouted, “Cam and headers.” That was enough to buy some high-performance parts for the car.

He knew there would be no cam and headers, he told me, when he heard Connie shout, “Washer and dryer!” A dragster’s rear end is enveloped in flame during a burnout prior to a quarter-mile run. A red 1968 Ford Galaxie like this one paid for the first washer and dryer.

The Fastest of them all The Fastest of them all

1 — 1970 Buick GSX 455 Stage 1

The GSX was produced to compete head-to-head with the likes of the Pontiac GTO “Judge” and Oldsmobile 442 W30. Only 400 Stage 1 GSX’s were produced. The base Buick GS also offered the Stage 1 option, but was only available in subdued paint colors without any of the GSX upgrades.

2 — 1970 Pontiac GTO Judge Ram Air

The “Judge” package on the popular GTO “added Ram Air, dual side eyebrow stripes over the front and rear wheels, rear deck lid spoiler, Judge decals, and the removal of the beauty rings from the painted Rallye II wheels. There were three engine choices available including the Ram Air III 400 (366HP), Ram Air IV 400 (370HP), and 455 H/O (360HP) options.

3 — 1969 Chevrolet Camaro COPOIV

COPO, which stands for Central Office Production Order, was a dealer ordering system that allowed fleet and municipal buyers to order special paint color options that weren’t available in regular production run vehicles. It also allowed for higher performance engine options to be ordered and installed where they weren’t normally available from the factory. ... The Camaro’s sole purpose was to dominate the NHRA Super Stock and NHRA/AHRA Pro Stock racing.

4 — 1969 Plymouth Road Runner, 440 Six Pack

Crowned Motor Trend’s Car of the year in 1969, the Plymouth Road Runner climbed to power due to its strong performance, variety of options, sharp looks, and affordable price tag. Plymouth executives didn’t ignore drag racing and hit it head on with the midyear A12 option. It included all the performance mods a professional drag racer would want but made them available direct from the factory.

5 — 1970 Chevrolet Chevelle SS 454 LS6

The Chevelle was Chevrolets’ midsized family model and the Super Sport option added a long list of high performance upgrades in the driveline and suspension that transformed it into a super car. The SS option also added styling upgrades including cowl hood, dual racing stripes, and hood pins. The LS6 454 cu.in. high compression engine produced a whopping 450HP—the highest advertised horsepower engine offered during the muscle car era.

6 — 1970 Oldsmobile 442 W

The legendary 1970 Oldsmobile 442 W30 was known as a refined high performance muscle car. 442 stood for 4-barrel carburetor, 4-speed, and dual exhaust. The W30 performance option added a 455 cu.in. V8, special “F” casting cylinder heads with larger intake and exhaust valves, higher flow port design, cast aluminum intake manifold, special camshaft with higher duration, and a specially tuned carburetor.

7 — 1970 Ford Torino Cobra, 429 Super Cobra Jet

The 1970 Torino looks like it’s going fast while standing still. The baddest Torino Cobra you could buy was the 429 Super Cobra Jet with the “Drag Pack.” It featured a 429 cubic inch high compression engine with 4-bolt mains, solid lifter cam, extreme oil cooler, free flowing intake, Holley 780cfm carb, and free flowing exhaust. It was bigger and heavier than a Mustang but could certainly keep up with them.

8 — 1970 Plymouth Cuda, 426 Hemi

The Hemi ‘Cuda featured dual 4-barrel carbs, dual quad intake manifold, heavy-duty radiator, 11-inch drum brakes, Shaker hood, 9.75-inch Dana rear end, and F60 tires on 15x7 Rallye wheels. The ‘Cuda model came standard with dual nonfunctional hood scoops, driving lamps on the front valence, red stripe grille, hood pins, “hockey stripe” decals on the rear quarter panels.

9 — 1969 Dodge Charger 500, 426 Hemi

The 1969 Dodge Charger 500 was one the great ‘Aero Warriors’ engineered for NASCAR. To improve its aerodynamics, Dodge fitted the Charger 500 with a flush mounted rear window and a flush mounted grille with fixed headlights. However, it didn’t eliminate enough drag on super-speedway so Dodge’s engineers went back to the wind tunnel and developed the 1969 Dodge Daytona.

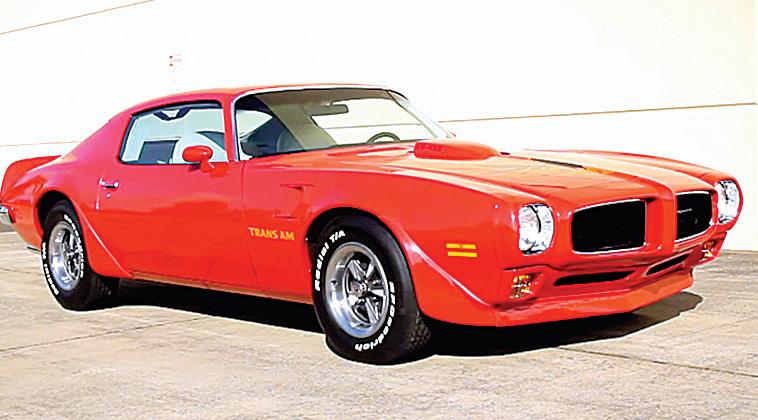

10 — 1973 Pontiac Trans Am Super Duty

While the deck was stacked against it with high insurance premiums, new NET horsepower ratings, reduced compression ratios, and the coming of unleaded gasoline, Pontiac engineers still delivered performance. In fact, the Trans Am SD-455 ended up being called ‘The last of fast cars by Pontiac’ by Car and Driver Magazine.

Tales from the Shop Tales from the Shop

By JOHN McCABE

Igrew up around gear heads.

Being raised in a family that owned auto parts stores – one of which included a full-service machine shop, the kind you simply don’t find today because it’s cheaper to replace an engine than rebuild it – meant that I was exposed from an early age to big blocks, small blocks, cams, cranks, valves and vats of sickly-sweet hot, inky-black liquid that would literally melt years’ worth of grease and gunk from an engine block in days.

Such an environment leads you to learn early on that grease under the fingernails is very hard to remove, even with an abrasive soap live Lava (many layers of skin have fallen to this particular green bar cleaner) or the lubricant-like consistency of Go-Jo, which literally made your hands and forearms so slick that grease slid off your skin. Grease and grime under the fingernails and embedded in the cracks of one’s hands also meant a hard day’s work in a job that helped support many families.

Spending considerable amounts of time at the shop on a fairly regular basis meant I also got to meet, talk to and learn from many middle-aged men who, even into the mid-1980s through the early 1990s, remained fascinated with the muscle car era. Their dedication and fascination with the Chevy SS 396, or the Oldsmobile 442, always intrigued me, and has led me to appreciate even more today just how unique and special muscle cars are to a certain segment of America.

As I got older I spent evenings, weekends and summers with my dad at the shop, and it was there that many colorful characters would congregate to shoot the bull, talk cars and, quite simply, be guys. The never-ending Ford vs. Chevy debate took place; I learned that the people who were Pontiac fans felt left-out because, after all, the GTO started the muscle car era but quickly received third-fiddle behind the Ford Mustang and the Chevrolet Chevelle; there also were endless opinions on just which engine produced the most horsepower; and I also quickly realized that Oldsmobile fans, though few in number, were the most diehard of them all.

Many customers would enter the shop with a “come listen to this” as they ushered us outside and revved up their tricked-out Road Runner or Nova with the glasspack exhaust.

Continued on next page

They would pop the hood to show off the bright gleam of chrome on the Edelbrock four-barrel carburetor and custom intake manifold. And inside the car, it was the Hurst shifter and custom tachometer on the dash that they wanted you to see.

They would seek opinions on which camshaft would give them more performance, and whether the “domed” piston head was better than the “flat-top.” They would tell stories from the drag strip at Eldora in Fairmont. Coffee flowed in abundance, and when groups of three or more got together, each story ended up being more outrageous than the last. I soaked in all of their accumulated wisdom, and recall fondly today many of their stories.

For me, it was always about the people, and their fascination with raw horsepower.

I’ll never forget “Julio,” a retired West Virginia state trooper who would drive for days to buy a Chrysler 350 engine. In the late 1980s he showed up at the shop late one evening, backing into the garage with a motor caked in mud in the bed of his truck. He had a big smile on his face as he explained that he had just returned from a three-day trip where he had dug the engine out from under a porch.

After a week in the vat and another week to bore the engine, refinish the heads and clean up the crank, Jose had himself a solid power plant that was ready to be reassembled and installed.

Then there was “Steve,” who loved putting V-8 muscle car motors in possibly the most ridiculous vehicles. He once brought a Chevy 350 to be refinished so he could drop it in an early 1980s Chevy Citation.

It was always interesting to listen to him talk about how much of the firewall he needed to remove, and how he would have to reinforce the suspension of his project cars to handle the extra weight. You learned plenty about how ingenious people could be in making something that’s not supposed to work actually work when they put their mind to a task.

Another one I’ll never forget is “Tony.” He was a regular who loved his big-block Chevy 454, not for his car or even his pick-up truck, but instead for his speedboat that he ran regularly on Cheat Lake. As anyone who’s ever owned a boat will tell you, there are only two times a man loves his boat — the day he buys it, and the day he sells it. But Tony ... well, what he loved wasto spend money on his boat, and particularly on the motor in his boat.

His goal, I recall, was to rattle the windows of the homes along the lake as he drove past.

And trust me when I say he spent the time and the money to make that happen.

There were hundreds of others interesting characters but for some strange reason, 30-plus years later, those three and their dedication to making things work stand out. I suppose their stories will stick with me for years to come.

While I loved listening to the stories and working with my hands to help my dad rebuild an engine, I never got into the whole “big block” mentality. It just wasn’t my thing. But I still have access to a 30-over Chevy 350 block and a perfect set of “202” heads. I also have a pristine 351 Windsor block with a set of 351 Cleveland heads that would make for a sweet setup. Now all I need is to find the right car and some free time to pursue this hobby.

Maybe one of these days …