THE [IMPOSSIBLE] ARCHIVE

by John Sita

Bachelors of Arts in Architecture

University of California, Berkeley, 2022

This thesis book was produced in the context of Professor James Leng’s seminar and studio ‘Figuring Ground’ 20232024, in partial fulfillment of requirements for the Master of Architecture degree at the University of California, Berkeley

May 2024

2024 John Sita. All rights reserved. ©

The author hereby grants UC Berkeley permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created.

Signature of Author

Certified by

Certified by

Department of Architecture

May 10, 2024

James Leng

Lecturer in Architecture

Thesis Advisor

Rudabeh Pakravan

Continuing Lecturer in Architecture

Thesis Advisor

1

Thesis Advisors

James Leng, M.Arch

Lecturer in Architecture

Rudabeh Pakravan, M.Arch

Continuing Lecturer in Architecture

THE [IMPOSSIBLE] ARCHIVE

by John Sita

Abstract

Human beings have certain basic needs in order to survive: food, water, air, and shelter. A shelter is defined as an architectural structure under which humans can dwell in safety, away from the harsh elements found in nature. This modern definition only came to be as a result of thousands of years of human and architectural evolution.

In an era of rapidly advancing technology, climate change, and human exploration beyond Earth’s borders that will inevitably change or possibly erase the current definition of shelter, this thesis attempts the “impossible” task of archiving the historical evolution of the essential architectural elements required for shelter (walls, doors, columns, windows, roofs, and floors) from the dawn of mankind to the present day in order to preserve their function and memory for future generations to rediscover if they are ever forgotten.

In confronting the philosophical and theoretical dilemmas of representing the entirety of mankind’s architectural history as it relates to shelter, this project deliberately moves from speculative inquiry to concrete realization in the form of an organized, enduring, and chronologically-mapped structural framework situated in the Tenere Desert near Agadez, Niger. While acknowledging the complexity and potential discomfort of this ambitious goal, the thesis not only embodies an experimental approach to archiving, but also aims to actively contribute to the discourse on preserving human cultural heritage in an era where such theoretical considerations may soon demand physical responses.

Primary

Advisor

Primary Advisor

James

Leng, M.Arch Lecturer in Architecture

James Leng, M.Arch in

Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 10, 2024 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Architecture degree

THE [IMPOSSIBLE] ARCHIVE

by John Sita

James and Rudy

Thank you for your incredible support and guidance in helping me along this ambitious journey. I’m truly grateful for your expert advice and constant encouragement that inspired me to explore and realize my ideas with confidence.

Lisa, David, and Roddy

Thank you for shaping my path in architectecture. Your mentorship not only provided me with a solid foundation in the field, but also inspired my sense of creativity in ways I hadn’t thought possible.

My Classmates

Thank you all for your camaraderie and collaboration throughout our studies. Pulling all-nighters together and critiques with you have been essential parts of my growth and made this journey all the more enriching.

Swim Club at Berkeley

Thank you to everyone I’ve met through swim club for providing much-needed entertainment when I wasn’t in studio. I will forever cherish the time spent in the water with you all and the lifelong friendships made.

Mom, Dad, and Rachel

To my family, your endless love, support, and encouragement have been my anchor throughout this journey. I am immensely grateful for your sacrifices and for always believing in me. You are my biggest supporters and my source of strength. Thank you for making me who I am today.

COL. — 3021

greek corinthian fluted column

Constructing the Archive [Impossibly]

Year 2524...

Appendix I: Final Review Presentation

Appendix II: Design Process Artifacts

Appendix III: The Phylogeny

Table of Contents 08 Introduction 15 The

22 Evolution

Shelter

59

08

08

33

Philosophy of Archiving

of

42

74

82

Bibliography

The Elements

8 REVOLVING DOOR DOOR — 17809 5-PANEL FOLDING DOOR INTRODUCTION

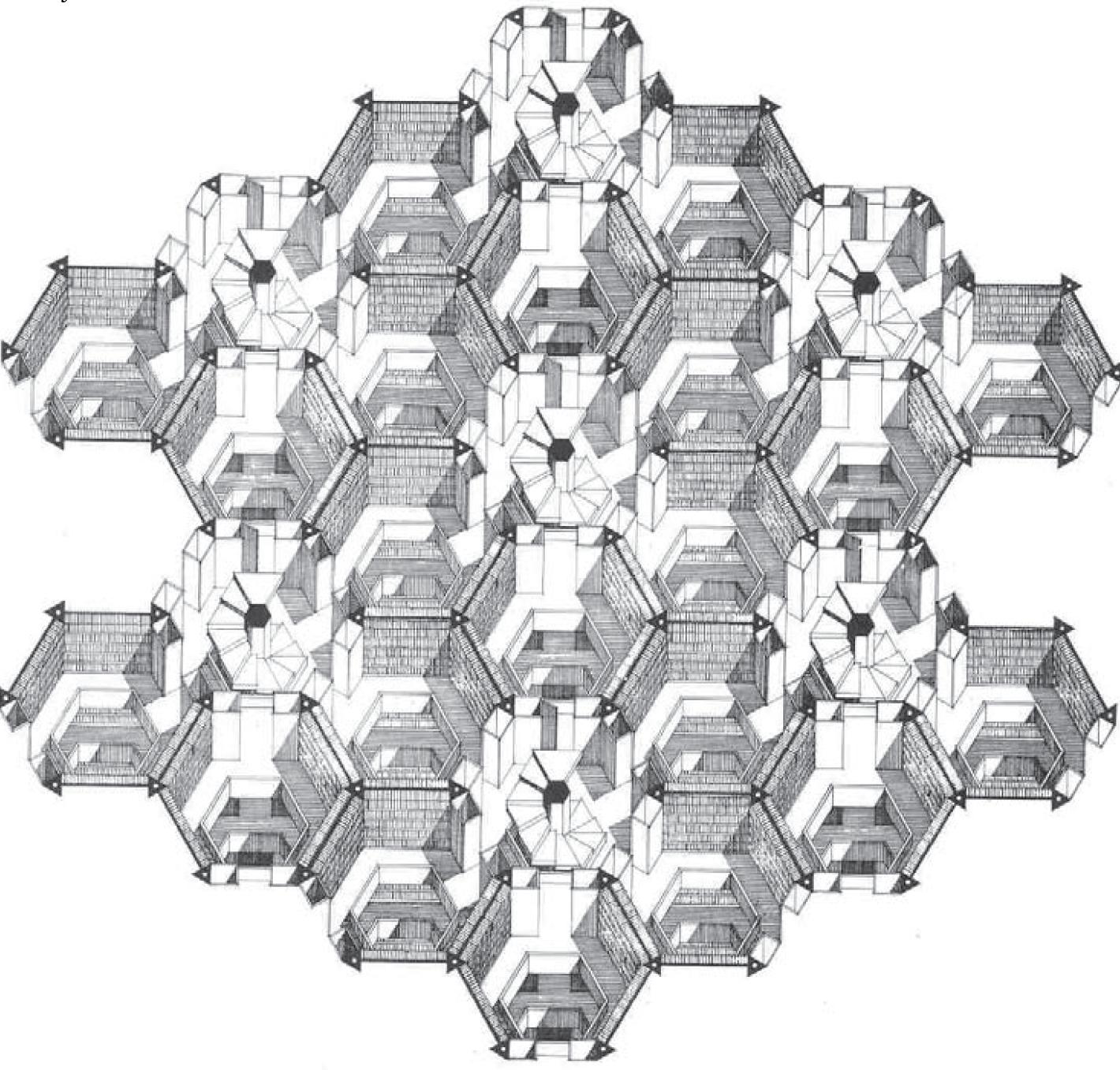

The initiative to establish a physical archive in the Tenere Desert dedicated to preserving humanity’s architectural heritage transcends mere conservation. It represents a profound engagement with the past and a deliberate communication with future generations. At its heart, the archive aims to catalog the structural elements—walls, roofs, columns, doors—that have sheltered humanity across the ages. These are the components that form the basic necessities of human habitats, from the simple yet effective shelters of ancient hunter-gatherers to the sophisticated, technology-infused buildings of the modern world. Jorge Luis Borges once imagined the universe as an infinite library, where each room holds the entirety of human knowledge and experience. Similarly, this archive seeks to act as such a repository, not merely storing information but safeguarding the physical embodiments of human ingenuity and the diverse expressions of cultural identity through architecture.

This project is underpinned by its significance in both a practical and symbolic sense. It aims to physically preserve crucial architectural elements while also symbolizing a bridge across time, linking the achievements of past civilizations with the unknown possibilities of the future.

The decision to locate this archive in the Tenere Desert is especially significant. Known for its vast, harsh landscape, the desert offers natural conditions favorable for preservation—dry air, minimal vegetation, and isolation from urban development. These qualities reduce the risks of environmental degradation and human interference, preserving the integrity of the stored materials. Moreover, the desert embodies the concept of timelessness and solitude, making it an apt metaphor for the eternal keeper of mankind’s architectural legacy, standing resilient as centuries pass.

Choosing the Tenere Desert as the archive’s location was driven by several critical factors, primarily its environmental stability and isolation. These characteristics are crucial in minimizing risks such as climatic variations, biological decay, and unauthorized human access, which could compromise the archive’s integrity. The stark, remote desert landscape also serves as a protective barrier, guarding the archive against the immediate effects of societal and technological changes that continuously reshape urban environments. This setting ensures that the archive remains untouched by time, making it an ideal vessel for preserving the purity of architectural knowledge. T.S. Eliot’s reflection that “History is now and England”

9

underscores the importance of understanding history as a dynamic narrative continually shaped by the present and viewed through the lens of current circumstances. Thus, the archive’s remote location also philosophically reinforces its role as a timeless repository, immune to the transient preoccupations of contemporary society.

The task of archiving architectural elements is fraught with challenges, both logistical and philosophical. Choosing which elements to preserve requires careful consideration, as it reflects broader societal values and cultural priorities. The process involves critical decisions about which aspects of our built environment are deemed essential for future generations. This act of selection is inherently subjective, influenced by current architectural trends, cultural significance, and historical value. Philosopher Michel Foucault’s insights in “The Archaeology of Knowledge” reveal the archive as a construct that not only preserves the physical but also shapes the narrative around what is remembered and how it is interpreted. The archive thus becomes a curated reflection of humanity, a deliberate composition of our cultural and technological milestones, curated to convey a particular narrative about the human experience.

In light of attempting to create an “impossible” archive, this thesis spans the philosophical rationale for such an endeavor, the practical challenges inherent in its realization, and the potential long-term impacts on how future generations will understand and value their architectural heritage. By constructing a robust and enduring archival framework, this project seeks to offer future societies a window into their past, providing them with the necessary context to appreciate and learn from the architectural feats and failures of their predecessors.

The theoretical backdrop of this thesis draws upon a diverse array of scholarly works that address the interplay of memory, space, and preservation. Notable among these is Gaston Bachelard’s “The Poetics of Space,” which offers profound insights into the significance of architectural spaces in shaping human experiences and emotions. Additionally, Alois Riegl’s seminal work, “The Modern Cult of Monuments,” provides a historical analysis of the motivations behind preserving cultural artifacts, which informs the contemporary understanding of why and how we choose to save certain elements of our built environment. These perspectives enrich the thesis by framing the archive not just as a physical space but as a philosophical

10

endeavor that challenges us to reconsider our relationship with our surroundings.

The subsequent chapters will delve into specific aspects of architectural evolution, the technical methodologies employed in the archive’s construction, and the broader implications of this initiative for future cultural and environmental landscapes. Through this detailed examination, the thesis aims to contribute significantly to the discourse on architectural preservation and its relevance in an ever-evolving world, ensuring that the legacies of past civilizations endure as both artifacts and instructive memories for those yet to come.

The importance of this thesis in the architectural discourse is underscored by its timeliness and relevance to contemporary global challenges such as climate change, war, and space colonization. As society confronts the undeniable impacts of environmental degradation, the concept of preserving architectural knowledge not only serves as a practical repository but also as a vital reservoir for future resilience and adaptation. Architectural historian Beatriz Colomina highlights the importance of architectural history in contemporary practice, stating, “Architecture is not simply

about shelter but fundamentally about how humans relate to the built environment, interact with it, and consider its impact on the future” (Colomina, 2016). This perspective is particularly relevant to this project, which seeks to archive critical architectural elements that have withstood the test of time and could inform future construction, both on Earth and potentially on other planets.

The prospect of interplanetary colonization further enriches the discourse, introducing new dimensions to the conversation on architectural sustainability and adaptability. As noted by space architect Madhu Thangavelu, “The architectural solutions we devise for other planets will undoubtedly echo the knowledge and experiences drawn from our terrestrial constructions” (Thangavelu, 2018). This thesis anticipates such developments, proposing that the archive could one day serve as a blueprint for constructing habitats in extraterrestrial environments, where the constraints and conditions differ markedly from Earth.

Acknowledging the subjective nature of selecting which architectural elements to preserve, this paper does not shy away from its inherent biases but rather engages them critically. As Michel Foucault remarked, “The archive is not an institution

11

that preserves an existing totality; it establishes and specifies what is written into it” (Foucault, 1972). Each decision regarding what to include in the archive reflects a complex interplay of historical significance, cultural values, and anticipatory utility for future needs. This project, by cataloging architectural elements, inherently participates in shaping the narrative of what is considered essential and worthy of preservation.

Ultimately, this thesis contributes significantly to architectural discourse by not only documenting a preservation effort but also by reflecting on and anticipating the evolving relationship between humans and their built environments. It challenges the field to consider more deeply how architecture can respond to global changes and how these responses can be systematically preserved and utilized in the future. This approach ensures that the thesis is not merely a static record but a dynamic, forward-looking contribution that seeks to influence future architects and theorists.

12

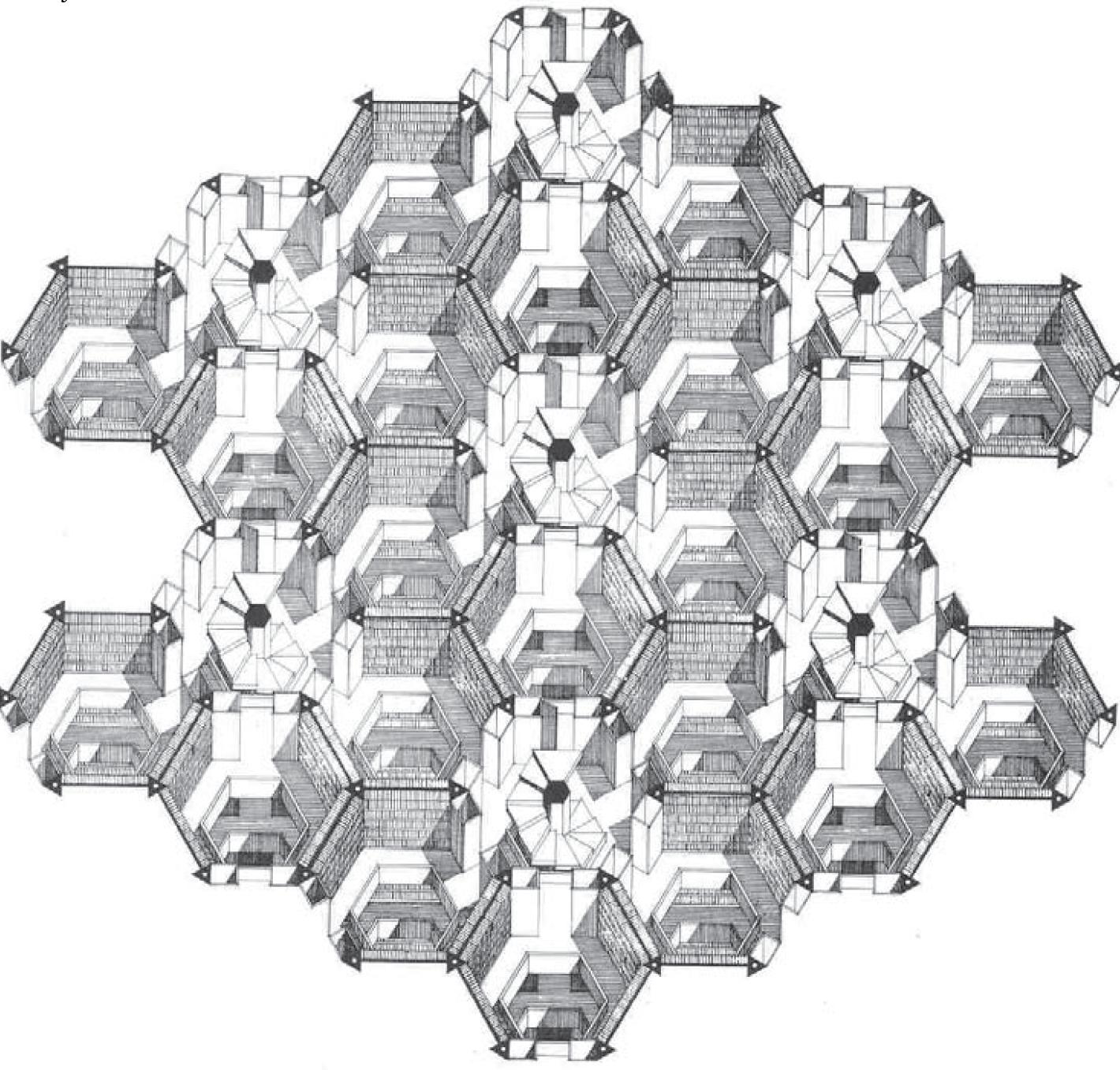

Figure 1: A floor-plan of the Library of Babel with two openings in each hexagon and a separate hexagon for each spiral staircase.

13

14 DOOR — 23128 CEILING-MOUNTED DOUBLE SLIDING DOOR fluted column WNDW. — 34532 BAY WINDOW

THE PHILOSOPHY OF ARCHIVING

HIP TRUSS

STRUCTURE — 203

15

HRZ

HRZ STRUCTURE

Archiving architectural elements involves more than storing physical objects; it embodies a deep philosophical quest to understand and preserve the narrative of human civilization. Jacques Derrida, in “Archive Fever,” illuminates this concept by suggesting that archives actively participate in shaping the narrative and interpretation of cultural and historical identities (Derrida, 1995). In this project, the architectural archive is envisioned not simply as a collection of static artifacts but as a dynamic entity that holds the potential to offer future societies profound insights into our era’s technological and cultural contexts. The process of selecting what architectural elements to preserve is influenced by a myriad of factors including historical significance, cultural values, and technological advancements. This selection process is inherently subjective, reflecting current societal values and the personal biases of those who curate the collection. Thus, the archive is not just a storage space but a curated reflection of humanity, shaped by the present yet intended to speak to the future.

The archive serves as a mirror, reflecting the diverse ways in which humans have shaped their environments through architecture. These are not merely functional narratives but are im-

bued with the aspirations and challenges of their times. French historian Jules Michelet’s insight that “Each epoch dreams the one to follow” captures the essence of this idea, suggesting that our built environments encapsulate not only practical solutions but also the hopes and fears of their creators (Michelet, 1831). By preserving a broad spectrum of architectural expressions, the archive initiates a critical dialogue about what constitutes progress and how it is represented and remembered. It ensures that future generations can access a diverse and comprehensive narrative that includes not just the triumphs of architectural ingenuity but also the socio-economic and environmental challenges that shaped these creations.

As we project into the future, the role of archiving must adapt to address the significant challenges of climate change, urban sprawl, and resource scarcity. The architectural archive itself must innovate, not only in how it preserves materials but also in how it makes these materials relevant to future needs. Stewart Brand in “The Clock of the Long Now” suggests that an archive, much like the Great Pyramids, should be robust enough to withstand not just physical decay over time but also the rapid shifts in technological and cultural

16

17

Figure 2: The Great Pyramids of Giza, Egypt

18

Figure 3: The Svalbard Global Seed Vault, Norway

contexts that could render its contents irrelevant or incomprehensible (Brand, 1999). Moreover, the advent of digital technologies offers new possibilities for archiving, allowing architectural knowledge to be stored in digital formats and accessed globally. This shift could democratize access to architectural knowledge, enabling a global audience to learn from and interact with the archive without the limitations imposed by physical distance.

The philosophy and functionality of architectural archives can be illuminated by examining modern examples where the preservation of physical objects is pivotal to broader scientific and cultural objectives. A quintessential example of this is the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, an endeavor that transcends typical archival activities by safeguarding a diverse array of plant seeds from around the globe. This facility, carved into the permafrost of a remote Norwegian island, aims to provide a backup against the potential loss of seeds in genebanks worldwide due to major global crises. The vault’s location and construction are meticulously planned to ensure the longevity and safety of its contents, offering a clear parallel to the goals of architectural archives in terms of protection and preservation.

Similarly, the Memory of Mankind project in Austria uses a series of ceramic tablets to store human knowledge and experiences. These tablets, buried deep within a salt mine, are designed to last for millennia, providing future generations with direct insights into our current era. This project underscores the broader implications of archiving efforts: they are not merely about saving physical objects but are about communicating with an unknown future, ensuring that crucial knowledge and cultural insights are not lost.

Moreover, digital archiving initiatives such as the Internet Archive aim to preserve digital artifacts, web pages, and even software, reflecting a more contemporary approach to the concept of an archive. These efforts highlight the evolving nature of archives—from physical repositories to digital collections—mirroring the changes in the way we produce, store, and value information and artifacts. The Internet Archive, for example, serves as a digital library offering free access to a wealth of information, playing a critical role in ensuring that the digital heritage of our time is preserved for future research and exploration.

The importance of these modern archives lies not only in their function as custodians of the past but

19

also in their proactive stance towards future crises and challenges. Like the architectural archive proposed in this thesis, these initiatives reflect a deep understanding of the precariousness of human knowledge and the fragility of our cultural artifacts. They are constructed with an awareness that future generations will require access to this heritage to learn, understand, and potentially overcome their own challenges.

Integrating these examples into the discourse on architectural archiving enriches our understanding of the potential and responsibilities of such endeavors. These modern archives provide practical examples of how theoretical objectives are implemented in real-world settings, offering valuable lessons on the complexities and necessities of preservation.

This exploration of the philosophy of archiving melds theoretical depth with practical application, proposing a multifaceted approach to architectural preservation. It invites architects, planners, and historians to engage deeply with the concept of legacy—considering not only the physical artifacts they create but also the cultural narratives they choose to preserve.

20

4: The Internet Archive Headquarters, San Francisco

21

Figure

EVOLUTION OF SHELTER

CAVE ~ 2.3 MILLION BC

22

LANDMARK 1

ROMAN INSULA ANCIENT ROME 1ST C. BC

PREHISTORIC HUT

TERRA AMATA, FRANCE

~ 400,000 BC

WIGWAM

~ 7,000 BC

23

LANDMARK 2

LANDMARK 1103

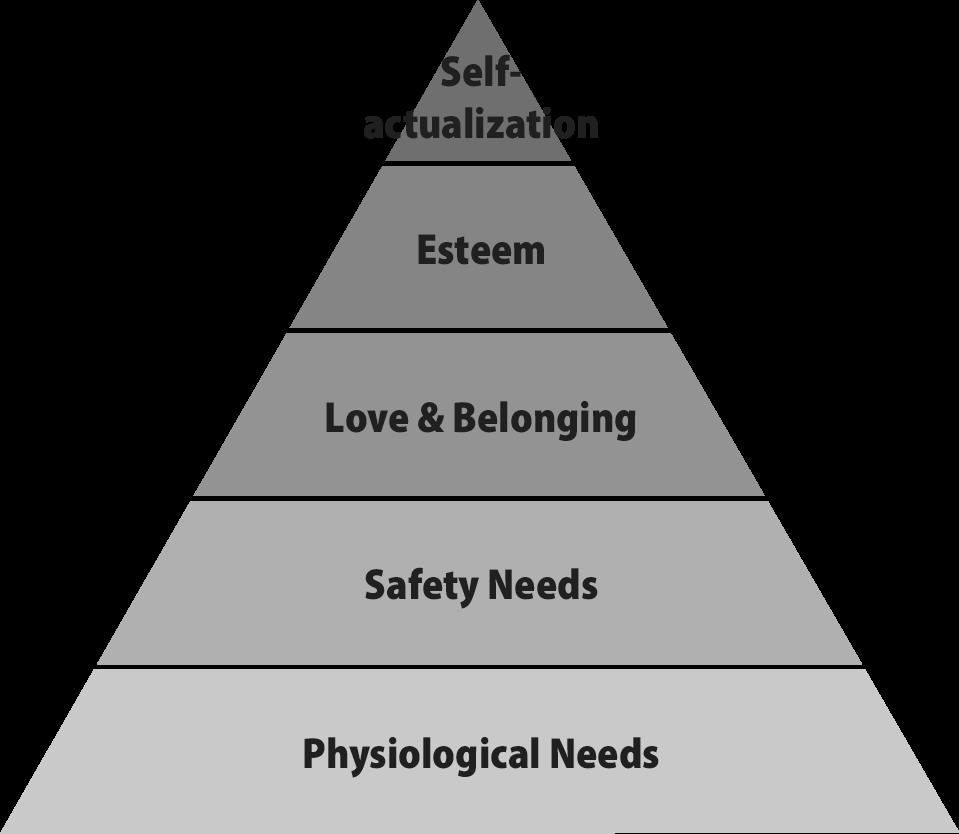

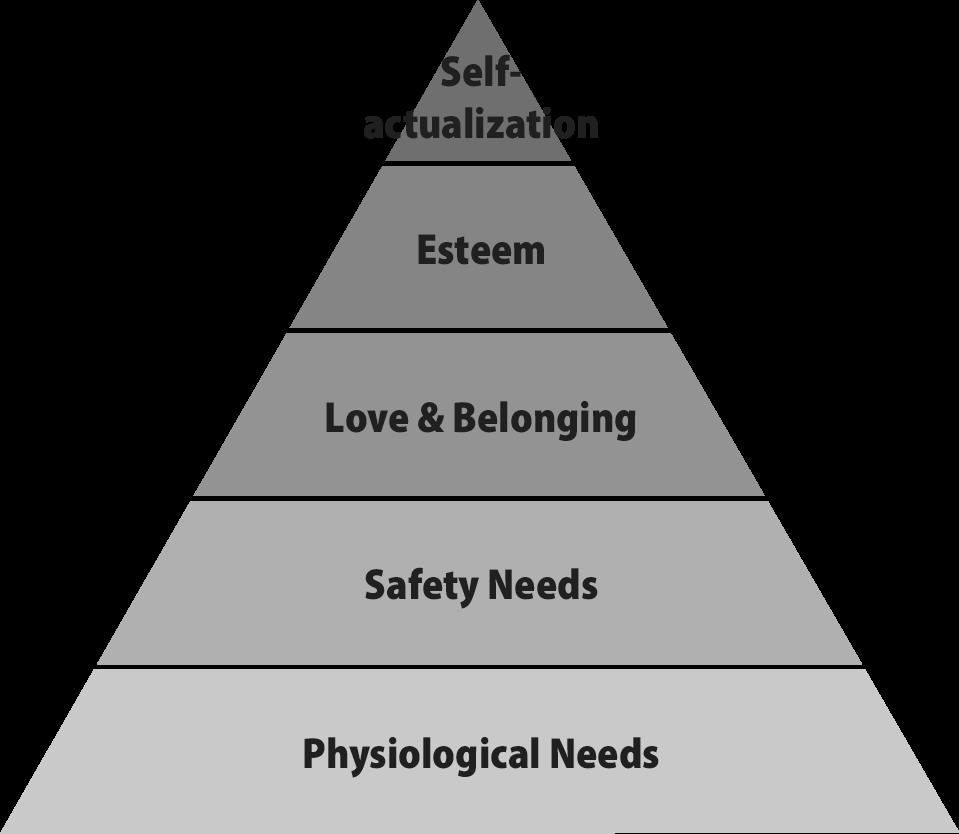

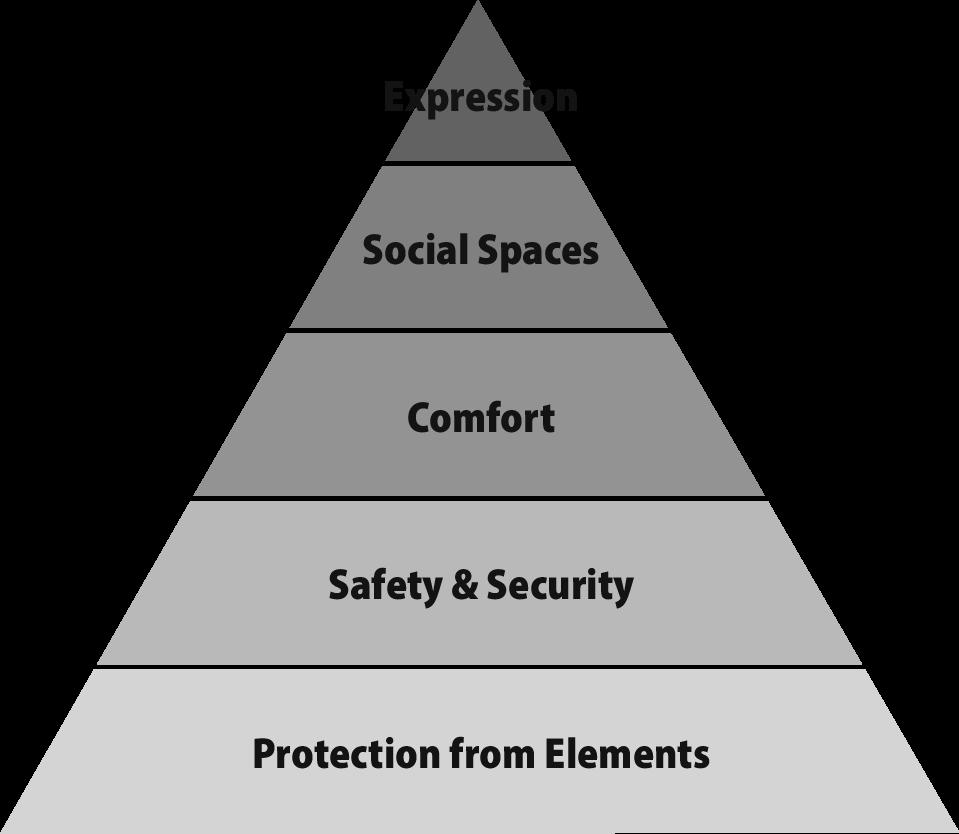

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a psychological theory that categorizes human needs into a five-level model, often depicted as a pyramid. At the base are the most fundamental needs for survival, such as food and water, followed by safety needs, which include security and protection. This model can be effectively applied to the concept of shelter, particularly when considering the evolution of human habitats from primitive shelters to modern housing.

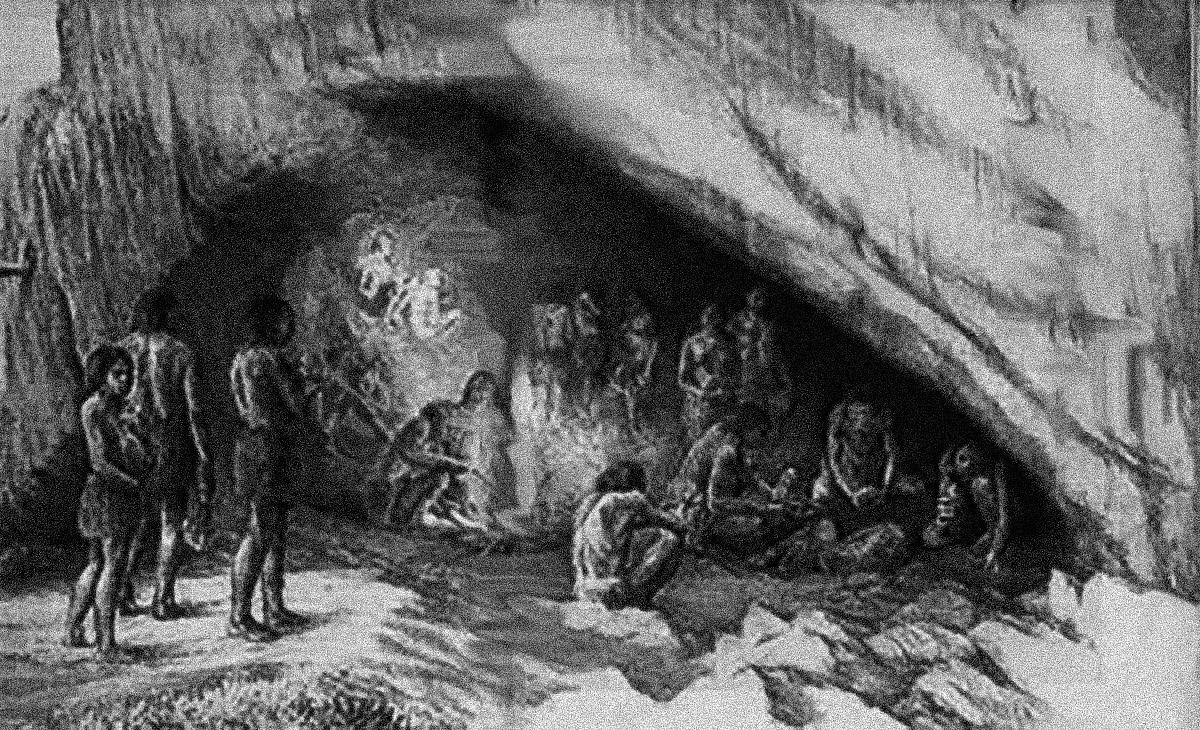

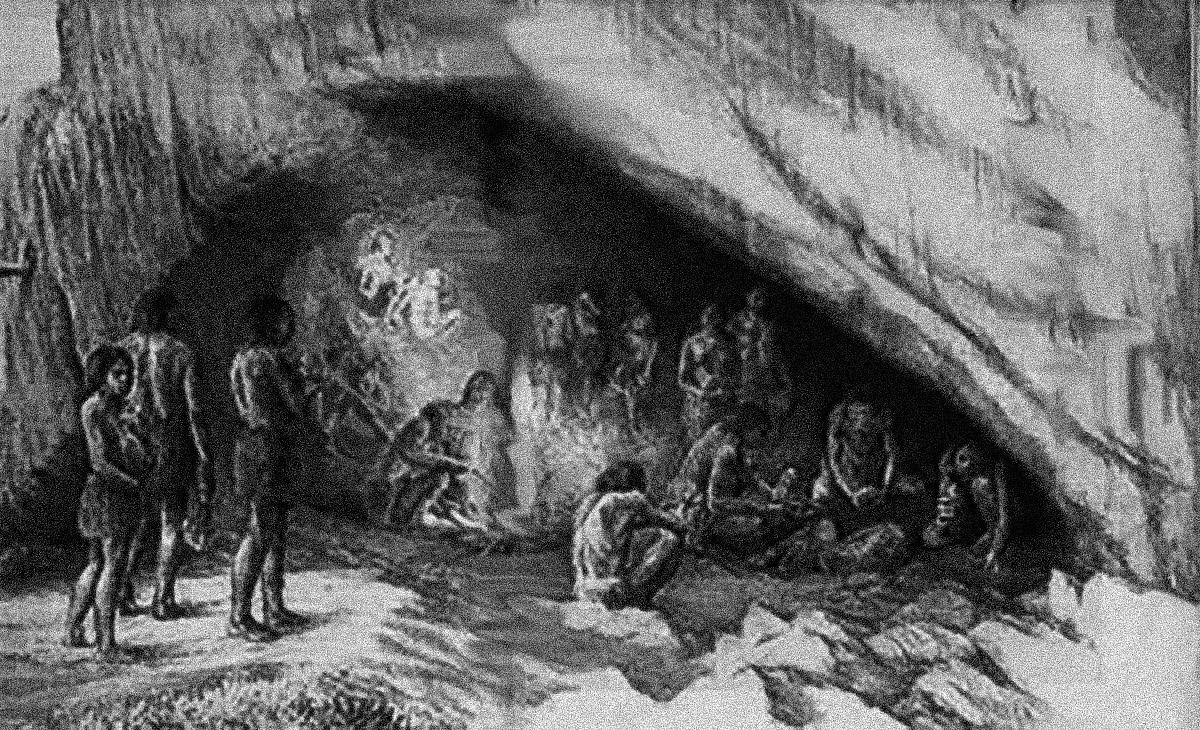

In the context of early human civilization, shelter was primarily about addressing these basic and safety needs. Natural formations like caves provided the first humans with protection against environmental hazards and predators, directly supporting their physiological and safety requirements. As Maslow’s theory suggests, once these basic needs were met, humans could focus on higher-level needs such as social belonging and esteem, which are reflected in the more complex social structures of later architectural developments.

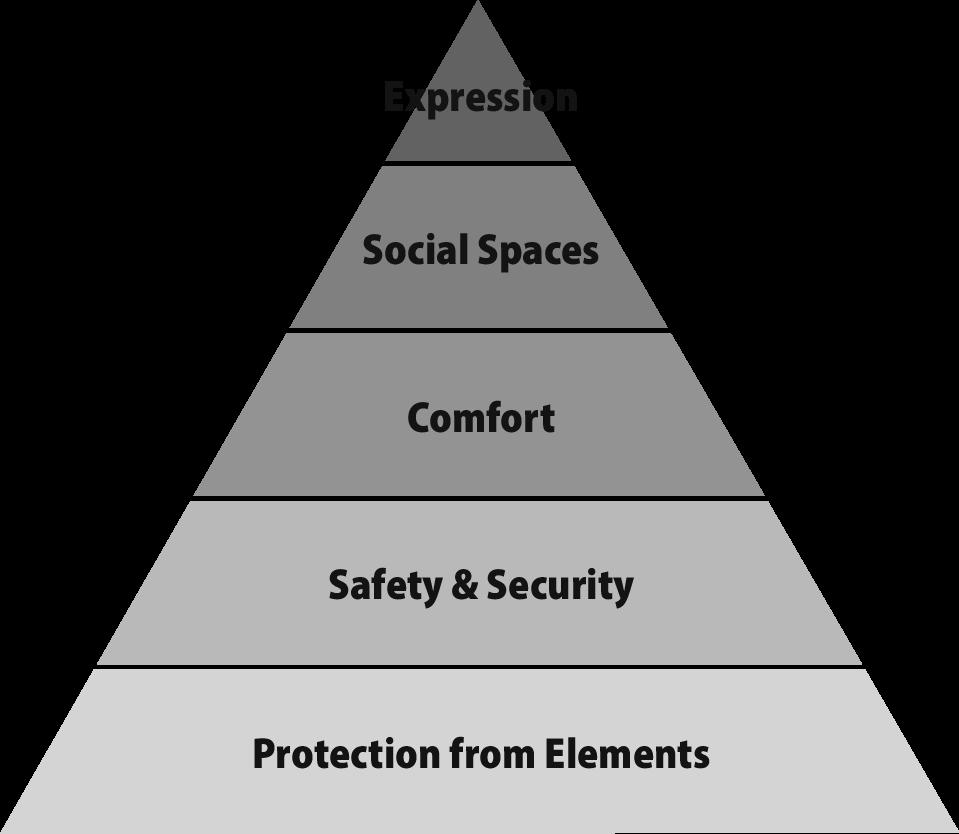

Adapting Maslow’s model to specifically address “Shelter’s Hierarchy of Needs,” we begin with the most fundamental aspect: protection from the elements. This basic need for physical safety is cru-

cial and was the primary function of early shelters. As shelters evolved, they began to address higher-level needs such as comfort and privacy, indicative of an increasing sophistication in design and purpose. This adapted hierarchy underscores how shelters have not only provided safety but also supported the psychological and emotional well-being of their inhabitants through considered enhancements in living conditions and communal spaces.

The earliest human shelters were fundamentally about survival—providing basic protection from the elements and predators. These initial shelters often utilized naturally occurring formations such as caves, which offered both protection and a constant temperature, crucial for early human groups facing harsh outdoor climates. The inherent properties of caves—cool in summer, warm in winter, and shielded from rain and wind—made them ideal initial habitats. Archaeological evidence suggests that these natural shelters were modified slightly with the addition of rough stone tools to enhance comfort or space, indicating the beginnings of deliberate architectural thought.

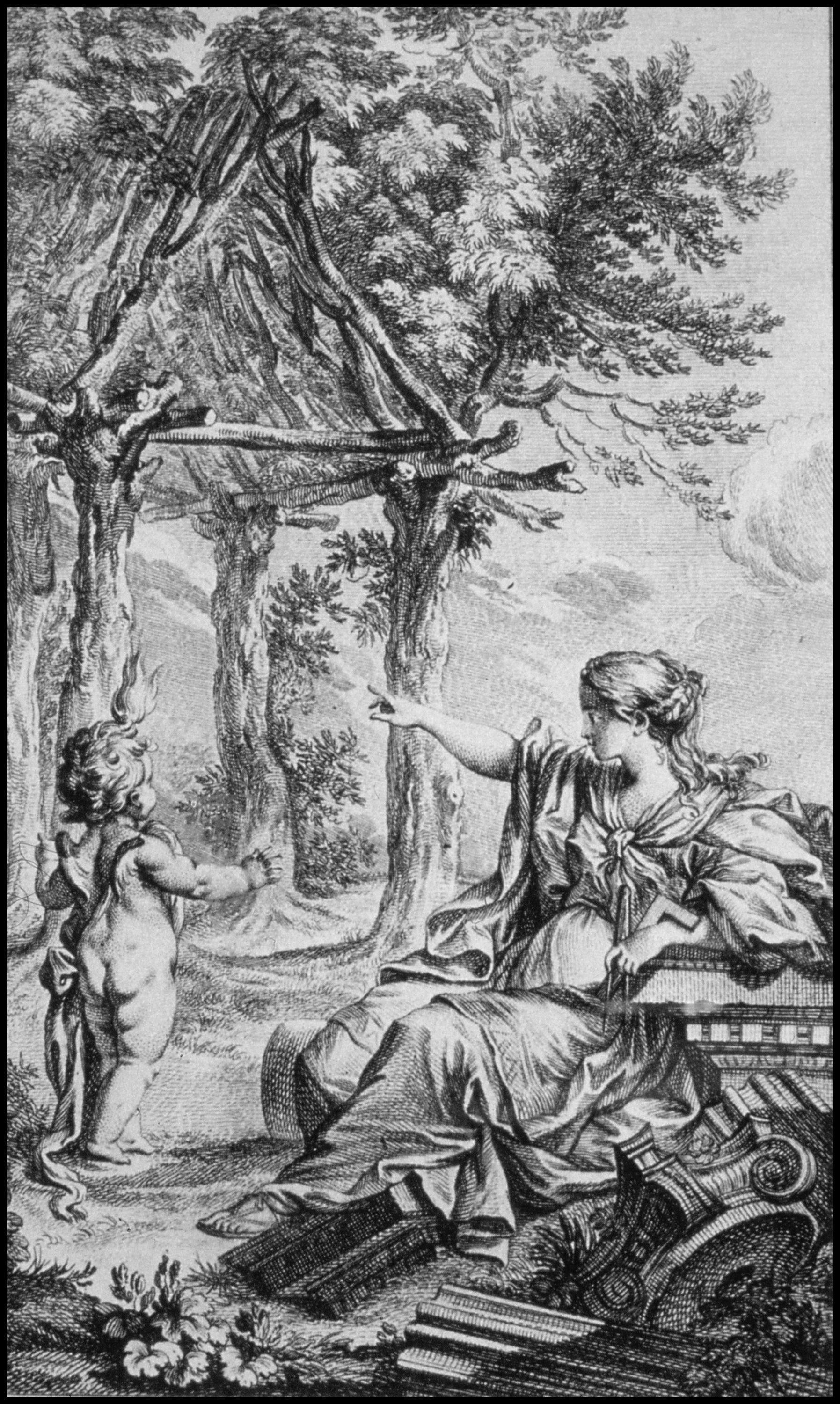

The philosophical underpinnings of these early architectural efforts are reflected in Marc-An-

24

25

Needs

Shelter’s Hierarchy of

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

toine Laugier’s 18th-century concept of the “primitive hut.” Laugier proposed that the ideal architectural form should embody the simplicity and functionalism found in nature. According to his theory, the primitive hut was constructed of tree trunks placed vertically as columns, supporting a horizontal beam as a basic lintel, with branches and leaves providing cover. This conceptual model highlighted the organic origins of architectural design, suggesting that the essence of architectural aesthetics and structure could be traced back to these rudimentary forms. Laugier’s ideas significantly influenced the neoclassical architectural movement, emphasizing clarity, simplicity, and symmetry, which mirrored the natural world’s intrinsic qualities.

Following the thread of Laugier’s primitive hut, various cultures adapted the basic design according to their environmental needs and available materials, leading to a diverse array of early architectural forms across different geographies. In tropical regions, primitive huts were constructed

with broad leaves and woven branches to maximize airflow and provide respite from heat and humidity, while in colder climates, compact designs featuring mud, stone, and animal skins helped retain heat and block cold winds. These adaptations illustrate the early human capacity to modify and refine their shelters in response to their surroundings, showcasing an evolving understanding of materials and environmental interaction that laid the groundwork for more complex architectural developments.

Ancient settlements such as Choirokoitia in Cyprus and Çatalhöyük in Turkey provide fascinating insights into the architectural evolution from simple natural shelters to more complex, community-oriented structures. Choirokoitia, one of the most well-preserved prehistoric sites in the Eastern Mediterranean, dating back to the 7th millennium BC, demonstrates early examples of communal living. The round stone houses, closely packed with shared walls, not only maximized space but also reinforced communal security.

26

Figure 5: A cave shelter occupied by early humans

27

Figure 6: Laugier’s Primitive Hut

28

Figure 7: Typologies of early man-made shelters

Figure 8: Dwellings at Choirokoitia

These structures, with small entry points that could be easily guarded and limited windows, speak to a sophisticated understanding of defensive architecture in a communal living context.

Similarly, Çatalhöyük, a Neolithic settlement in southern Anatolia from around 7500 BC, showcases some of the earliest known examples of agglomerated dwellings. The houses in Çatalhöyük were made from mud bricks and were accessed via roofs that also served as communal walking areas. This unique arrangement suggests a highly integrated community without clear streets, where roofscapes provided communal space, reflecting a complex social structure that required innovative architectural solutions. Inside, the houses contained elaborate burials beneath platforms and featured wall paintings, indicating a rich cultural life that integrated spiritual and aesthetic elements into the fabric of daily living.

In ancient Greece, the simplicity and functionality of housing reflected the polis-centric culture, which valued civic engagement and communal identity. According to Vitruvius, the homes were “commodious and suited to the habits of the people” (Vitruvius, 1st Century BC), emphasizing the Greeks’ strategic use of locally sourced materials like sun-dried bricks, which contributed to the thermal comfort and sustainability of their dwellings.

Moving to the Roman architectural landscape, the complexity of Roman houses like those in Pompeii highlighted an advanced understanding of residential spaces that catered to both private and social needs. According to Wallace-Hadrill, homes in Pompeii were “expressions of the self and containers of memory” (Wallace-Hadrill, 1994), indicating that beyond their practical purposes, Roman homes also served as cultural repositories

29

Figure 9: Village of Çatalhöyük

reflecting personal and familial identities.

During the Middle Ages, the vernacular architecture of the time, such as the timber-framed houses of northern Europe, was distinctly adapted to local climates and available resources. These structures, with their sturdy wooden frameworks and wattle and daub infill, provided necessary insulation during harsh winters. As Carsten Paludan-Müller notes, “These houses were not merely functional but were also significant as cultural expressions of the medieval societal structure” (Paludan-Müller, 1986), showcasing the deep interrelation between architectural forms and the social hierarchies of medieval Europe.

In contrast, the indigenous architecture of the Andes, exemplified by the precision stone masonry of Machu Picchu, utilized a technology that was both highly advanced and perfectly adapted to its mountainous environment. According to Wright et al., “The Incas’ ability to integrate their architecture into the high Andes landscape using native materials and techniques demonstrates their deep connection to the natural world” (Wright et al., 2000). This integration was not only practical but also spiritual, embedding the civilization’s cosmological views into its architectural fabric.

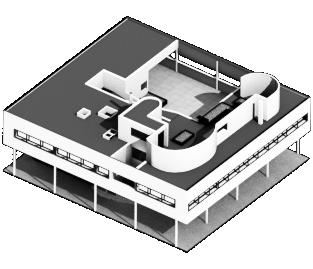

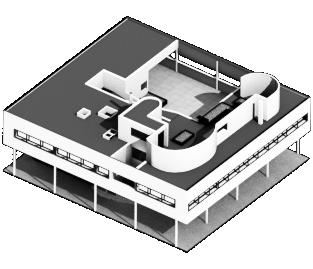

The 20th century brought forth the modernist movement, where architects like Le Corbusier redefined what shelter could mean in the modern world. His Unité d’Habitation was a radical rethinking of communal living, offering a vision where “a house is a machine for living in” (Le Corbusier, 1927). This philosophy emphasized efficiency, light, and the collective arrangement of living spaces, promoting a new architectural language that sought to respond to the industrial age’s challenges.

Parallel to these developments, the traditional shelters like the African Dogon homes used organic forms and materials to achieve thermal comfort and environmental integration. Researchers have noted that “The Dogon’s use of mud and thatch is not only practical in its climatic responsiveness but also significant in maintaining the cultural continuity of their community” (Prussin, 1995). This highlights how native architectural practices, while often overlooked in the global narrative, provide key insights into sustainable living and community-based design.

30

LANDMARK 4853

ADOBE HOUSE AMERICAS ~3000 BC

LANDMARK 43824

31

VILLA SAVOYE POISSY, FRANCE

1931

roof door horizontal structure

32

column

THE ELEMENTS window

floor 33

wall

In the ambitious endeavor to archive the evolution of shelter, identifying essential architectural elements such as walls, roofs, floors, horizontal structures, columns, windows, and doors became a critical task. These elements were chosen not merely for their ubiquity in constructions throughout history but because they encapsulate the core functions and innovations of shelter. As articulated by Rem Koolhaas in his extensive work “Elements of Architecture,” these components are “the fundamentals that construct our environments” and are “eternally consistent and infinitely variable” (Koolhaas, 2014).

Walls and roofs, for example, are primary in providing the basic protective function of shelter, delineating interior from exterior and providing security and privacy. Floors create the literal foundation upon which all other elements rest, defining the separation between the earth and the human-occupied space. Windows and doors serve as the critical points of interface between the inside of a shelter and the external world, providing ventilation, light, and access—factors essential for a habitable space.

Koolhaas further elaborates on how these elements have been reinterpreted through various epochs, adapting to new materials, technologies, and cultural imperatives yet always serving fundamental needs. From the simple mud walls of

ancient dwellings to the glass curtain walls of modern skyscrapers, each iteration of these elements speaks to both the era’s technological limits and its architectural aspirations.

The process of identifying these elements for the archive involved a meticulous examination of architectural history, focusing on innovations that significantly advanced the functionality and conceptual understanding of shelter. This inquiry was guided by a theoretical framework that recognized the dual role of these elements in practical application and symbolic representation. By preserving these fundamental components, the archive aims to offer future generations not just a repository of architectural forms but a lens through which to view the challenges and solutions that shaped human habitats.

This approach aligns with broader historiographical practices in architecture where, according to scholars like Spiro Kostof, the study of built forms is not merely about documenting styles but understanding “the very nature of built environment” as a mirror of human life (Kostof, 1985). Thus, the archive does not only preserve the physical manifestations of these elements but also their conceptual evolution, reflecting shifts in human needs, environmental adaptations, and technological progress.

34

WALL — 9258

CONCRETE MASONRY WALL

WALL — 2435

REINFORCED CONCRETE WALL

WALL — 10849

GLASS BLOCK WALL

wall

The wall, as an essential architectural element, stands as both a fundamental and transformative component in the evolution of shelter. Koolhaas describes the wall as “both barrier and gateway,” emphasizing its dual role in protecting and defining spaces.

DOOR — 23128

Historically, walls were primary in defining and securing spaces, offering protection from environmental elements and delineating private spaces. From ancient stone fortifications to the elegant walls of palatial residences, and on to the stark surfaces of modern architecture, walls have consistently been at the core of both functional and aesthetic architectural expressions.

CEILING-MOUNTED DOUBLE SLIDING DOOR

The wall’s evolution also highlights advances in materials and construction techniques, reflecting broader technological and social shifts. For example, early mud and straw walls not only provided shelter but also moderated interior climates. Later developments, like curtain walls in contemporary buildings, illustrate advancements in material science and design philosophy.

In the archive, walls are presented not just as structural components but as embodiments of cultural, technological, and artistic progress. The diversity of wall types—from load-bearing ancient walls to modern glass facades—provides insights into how shelter has adapted through time.

35

POCKET DOOR

WNDW. — 34532

greek corinthian fluted column

— 72947

BAY WINDOW FLOOR

roof

As detailed by Koolhaas, the roof stands as a vital architectural element, symbolizing shelter and protection across various cultures and eras. Its primary role has always been to shield interiors from environmental elements, which is central to its celebration in the archive as a key element in the evolution of shelter.

Roofs have historically demonstrated a wide array of materials and techniques, adapting to different climates and technological advancements. From thatched roofs in traditional rural settings to the sophisticated geometric structures in modern architecture, roofs showcase how architectural innovation can meet both functional needs and aesthetic desires.

Moreover, roofs have served as a canvas for architectural expression, influencing the skyline and character of buildings. This is evident in structures like the steeply pitched roofs of Gothic cathedrals, which not only facilitated water runoff but also enhanced the structures’ spiritual and aesthetic appeal.

In the archive, roofs are more than just protective covers; they are portrayed as integral components that reflect the technological progress and cultural contexts of their times.

36

28045 DOOR DOOR — 17809 FOLDING 19762 DOOR DOOR — 16236 POCKET DOOR DOOR

13043 ROOF

GABLE ROOF

—

— 23

floor

The floor is foundational to any built environment, providing the literal groundwork for all architectural activities. Its importance in the evolution of shelter and its dual function as both a structural and cultural element make it a focal point in the archive.

Throughout history, the development of floors has tracked closely with advancements in construction and materials. From the earth-packed floors of early dwellings to the intricate mosaics of Roman estates and the polished concrete or wooden floors of contemporary buildings, each evolution reflects significant shifts in technology and design aesthetics.

EGYPTIAN COLUMN

The choice of flooring materials has also historically denoted socioeconomic status; stone floors in medieval castles symbolized wealth and power, while simpler materials like straw or wood chips in common homes indicated lower economic standing. This variation highlights the diverse human experiences and cultural contexts represented by floors.

In the archive, floors are presented not just as structural bases but as integral components that reflect the technological progress, cultural practices, and aesthetic choices of their times.

37

23128

COL. — 1704

WNDW. — 34532 ARCHED SLIDING FLOOR — 64830 HIP TRUSS FLOOR

36321

—

FLOOR — 72947

HIP TRUSS

horizontal structure

SLIDING WINDOW

HRZ STRUCTURE — 203

Horizontal structures such as beams and trusses are crucial for spanning spaces and supporting floors and roofs within buildings. Their role is central in architecture, facilitating the construction of expansive, open interiors and defining the very form and functionality of shelters.

These structures have evolved significantly, from rudimentary wooden beams used in early structures to advanced steel and concrete frameworks in contemporary architecture. This progression not only reflects advancements in engineering and materials but also shifts in architectural priorities—such as the modernist emphasis on open floor plans and unobstructed spaces.

In the archive, horizontal structures are celebrated for their technological and aesthetic contributions to architecture. They are essential not just for their structural roles but for how they have enabled innovations in building design and influenced the use of space.

HRZ STRUCTURE — 157

SCISSOR TRUSS

38

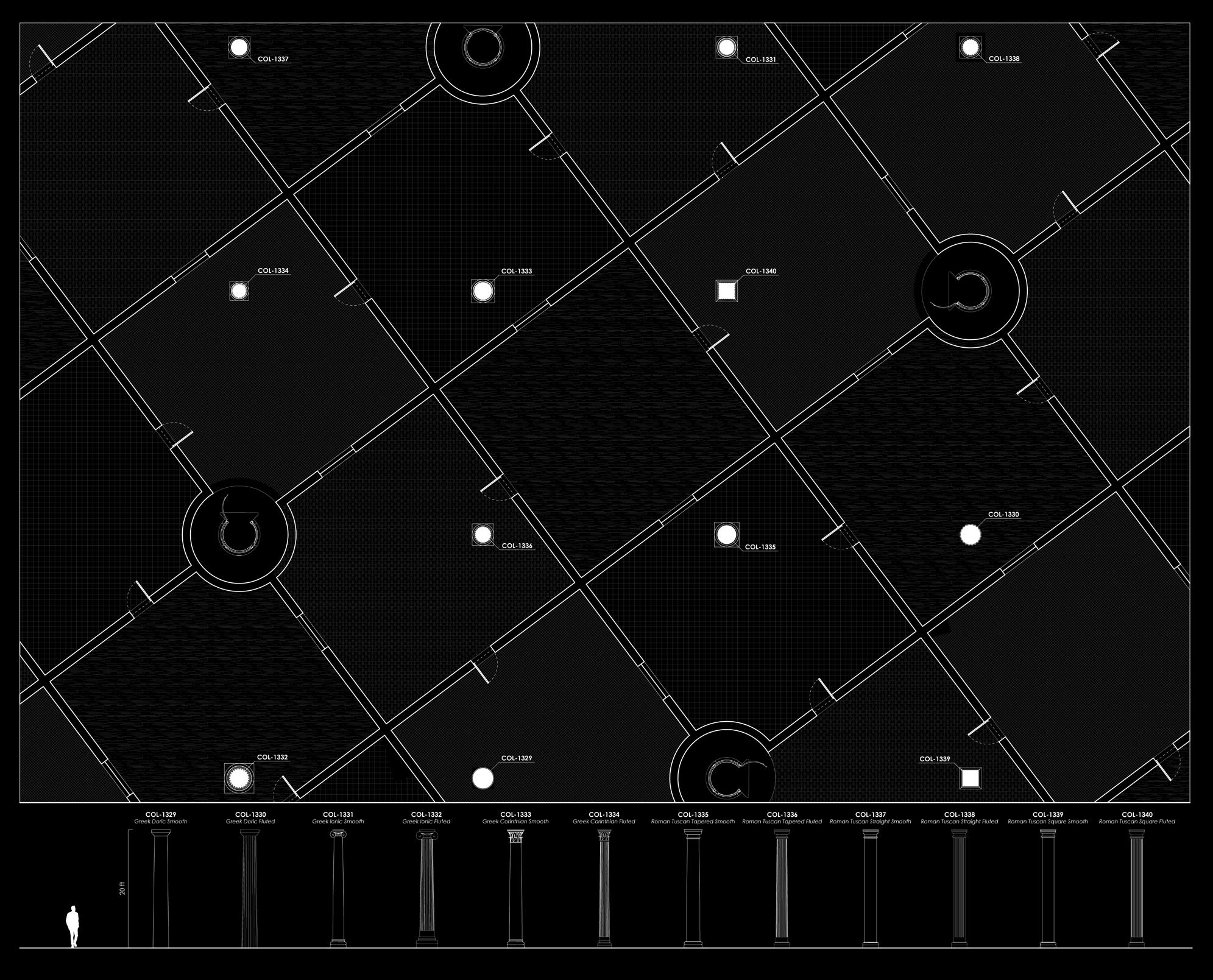

column

Columns are essential for both structural support and aesthetic expression in architecture. They embody the architectural interplay between strength and beauty, which has been crucial throughout the evolution of shelter.

Traditionally, columns have served to support significant loads and define the aesthetic character of spaces, from the ornate Corinthian columns of ancient Greece to the sleek steel columns in modern high-rises. This evolution from stone and wood to steel and concrete has allowed for architectural innovations that challenge previous limits of height and span.

In the archive, columns are celebrated for their dual role as structural necessities and as markers of architectural style. They provide a lens through which to view advancements in construction technology and shifts in aesthetic over time. Each column serves to speak to the technological capabilities and cultural values of its period.

39

EGYPTIAN COLUMN WNDW. DOUBLE ARCHED WNDW.

COL. — 1704

COL. — 1704

window

EGYPTIAN COLUMN

Windows are vital architectural elements that mediate between the interior and exterior, providing light, ventilation, and views while shaping the aesthetic of buildings. Their evolution from small, unglazed openings in ancient structures to the expansive glass facades of modern skyscrapers marks significant advancements in technology and design aesthetics.

Initially simple and functional, windows became larger and more integral to building design with advances in glass making during the Renaissance, enhancing natural lighting and visual connectivity with the outdoors. The Industrial Revolution further transformed windows with the introduction of stronger glass and metal frames, leading to the modern era’s characteristic large glass panels that dominate architectural facades and influence interior environments.

In the archive, windows are celebrated not only for their functional role but also as key indicators of technological and design evolution in architecture. They are presented to illustrate how changes in window design reflect broader shifts in construction methods, materials, and the understanding of space and light in building interiors.

WNDW. — 21874

DOUBLE HUNG ARCHED WINDOW SLIDING WINDOW

WNDW. — 28093

40

HIP TRUSS

door

DOOR — 16236

DOOR — 19762

As described by Koolhaas, doors are fundamental in architecture, offering both practical utility and symbolic meaning by defining transitions between spaces. They provide security and privacy, serving as vital points of entry and exit that also demarcate boundaries within the built environment.

The evolution of doors has paralleled advancements in building techniques and materials, from the robust bronze doors of ancient Rome to the ornately detailed wooden doors of medieval times and the modern automated doors of glass and steel. Each reflects the technological capabilities and aesthetic preferences of its time, also indicating changes in societal values regarding security and privacy.

In the archive, doors are celebrated for their role in architectural functionality and as cultural artifacts. Showcasing different styles and mechanisms, the archive illustrates how doors have adapted to meet varying needs of security, convenience, and representation, marking them as more than mere entry points but as significant components in the narrative of architectural evolution.

41

DOOR — 17809

DOOR — 28045 REVOLVING DOOR

GARAGE DOOR

POCKET DOOR

CONSTRUCTING THE ARCHIVE [IMPOSSIBLY]

44

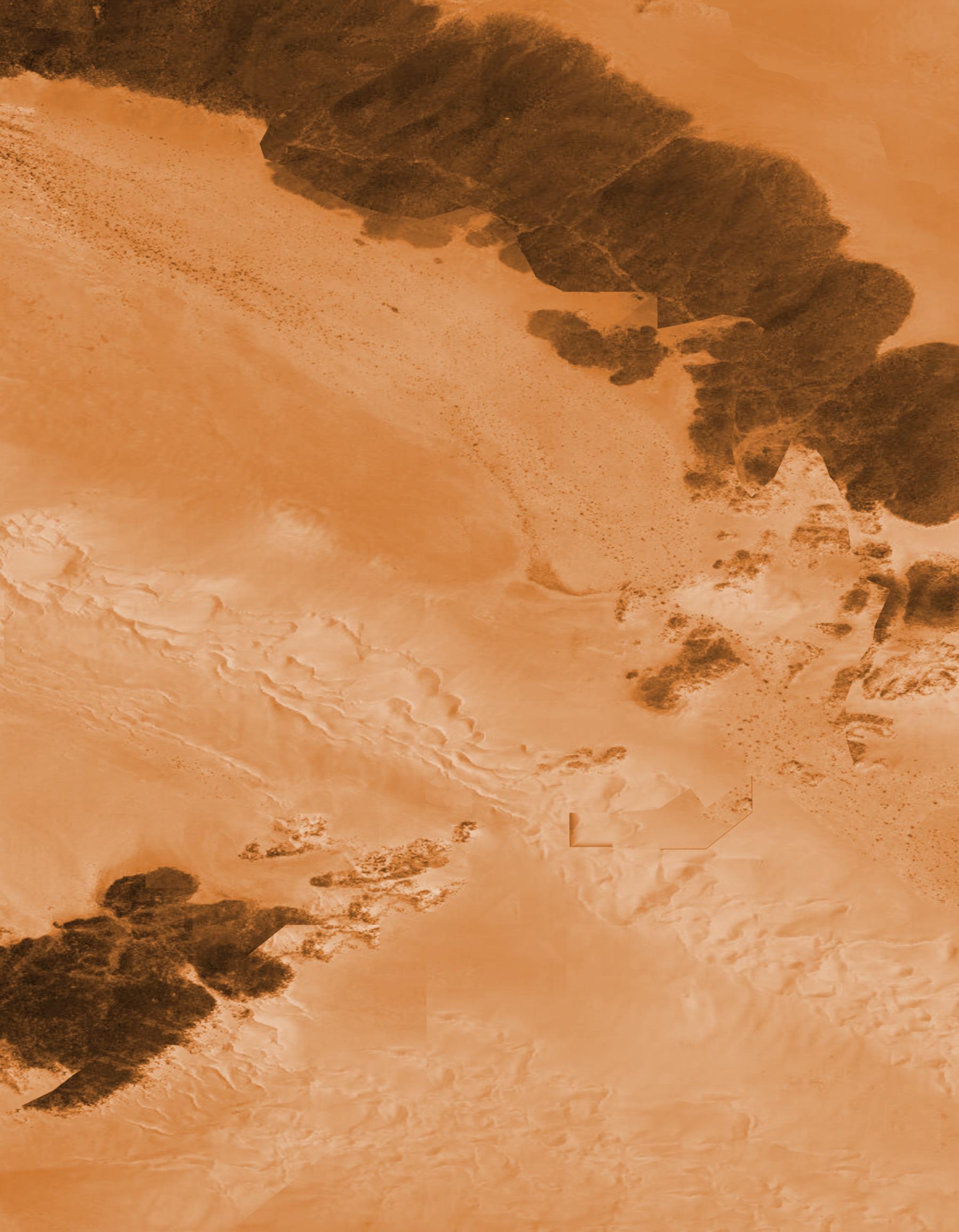

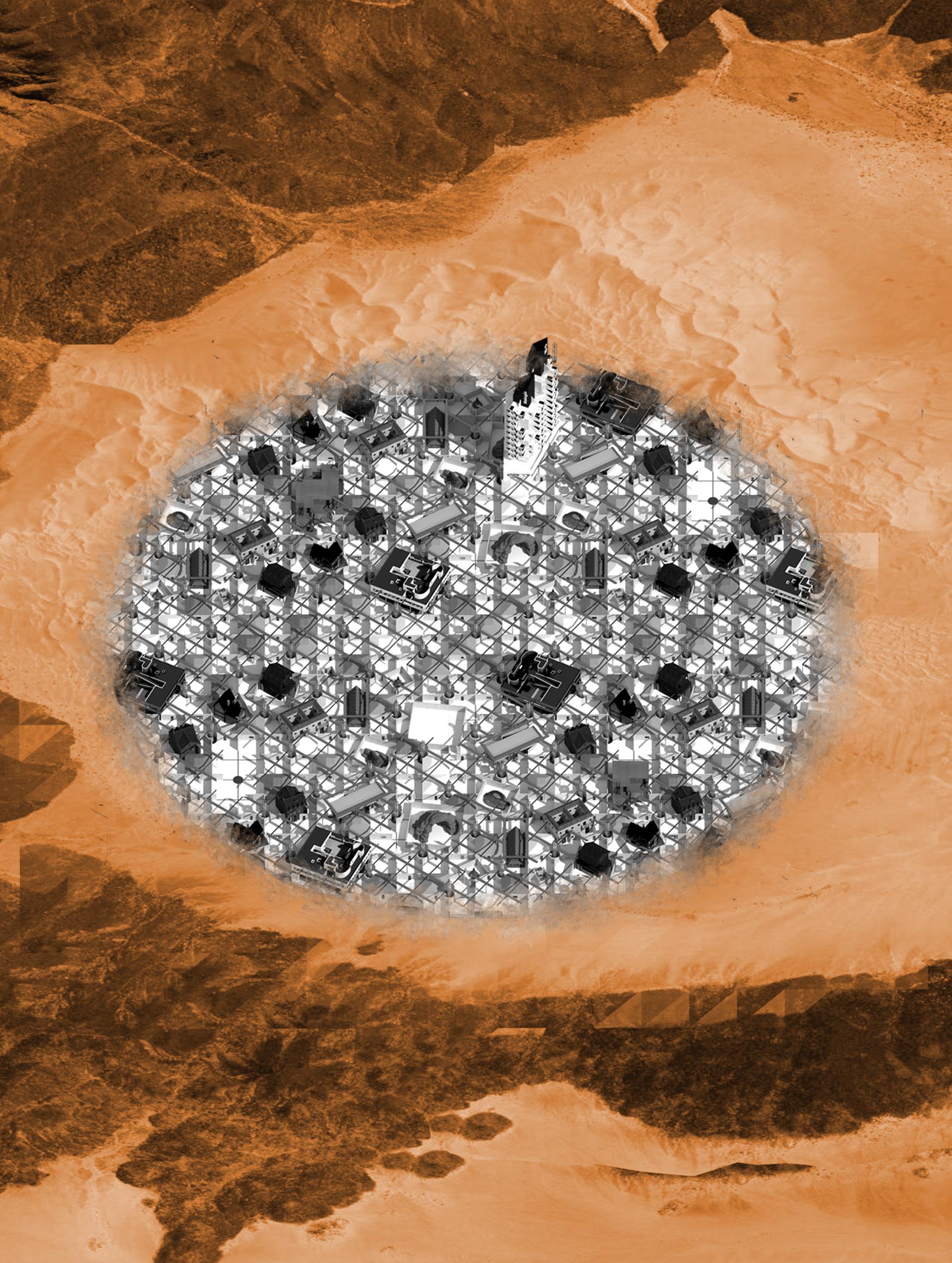

Figure 10: Satellite View of Arakao Crater

Figure 11: Arakao Crater Dunes

THE TENERE DESERT

The Tenere Desert, part of the larger Sahara in North Africa, is characterized by its vast expanses of sandy dunes and extreme aridity, which create an environment uniquely suited for preservation. The Arakao Crater, nestled within these extensive desert landscapes, provides an exceptional site for the archive. This specific location not only capitalizes on the natural dryness, which is beneficial for preserving materials sensitive to moisture, but also leverages the geographical features of the crater for added protection.

The desert’s low humidity levels are crucial in slowing the degradation processes that affect organic materials, as well as metals which are prone to corrosion in more humid environments. According to research published in the “Journal of Arid Environments,” desert conditions are noted for “their ability to help preserve artifacts and structures from the corrosive effects of moisture and mold” (Smith, 2002). The constant dry state of the desert helps ensure that materials like paper, textiles, and wood maintain their integrity over extended periods, free from the deteriorative effects that humidity can induce.

Moreover, the Arakao Crater itself provides ad-

ditional environmental shielding. Its unique topographical features create a natural barrier against the elements, particularly wind-driven erosion and sand deposition, which can be detrimental to exposed structures. The crater’s walls help in mitigating these effects, creating a somewhat controlled microenvironment within the vast desert. As noted by geologist Dr. Helen McGregor, “Crater formations, with their enclosed structure and often reduced wind speeds, can significantly protect internal contents from the external abrasive forces commonly found in desert landscapes” (McGregor, 2005).

Choosing the Arakao Crater Dunes within the Tenere Desert for the archive also makes sense from a conservation perspective. The isolation of the site minimizes human interference, which is a critical factor in the preservation of heritage sites. This remoteness not only reduces the risk of vandalism and theft but also ensures that the environmental conditions around the archive remain stable and unaltered by human activity.

45

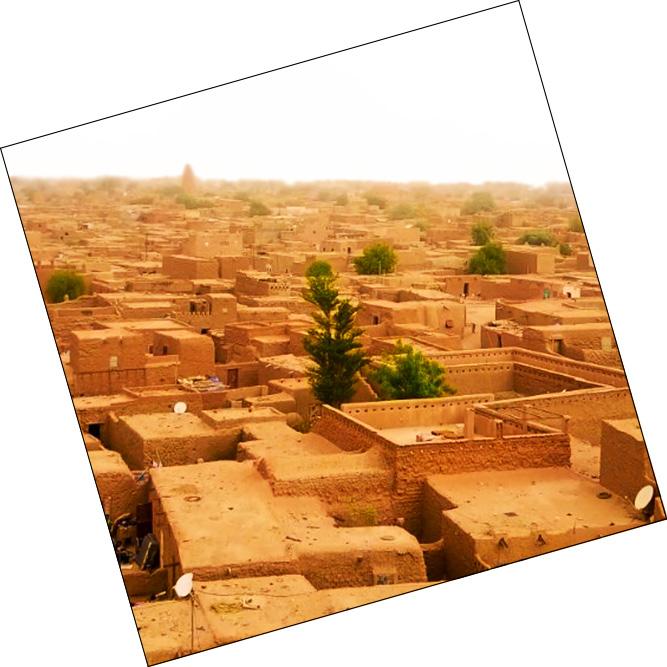

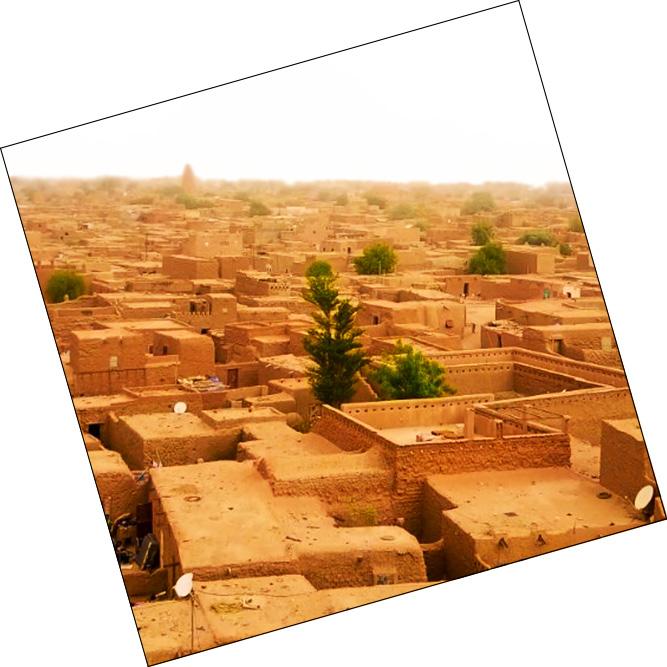

AGADEZ, NIGER

Agadez is a town situated on the edge of the Tenere Desert in Niger, and it plays a crucial role as a logistical and resource hub for the archive. Historically a center of commerce and a crossroads of Saharan trade routes, Agadez offers vital infrastructure and accessibility to the otherwise completely remote site. Its proximity to the desert makes it an ideal staging ground for transporting materials and personnel necessary for the construction and maintenance of the archive.

As a resource hub, Agadez provides essential supplies and local labor, which are pivotal for the ongoing development and sustainability of the archive. Leveraging the town’s established supply chains helps in minimizing the logistical challenges associated with building in a remote desert location. Furthermore, the presence of a local workforce familiar with the desert’s environmental conditions and challenges ensures that the construction and upkeep of the archive are managed efficiently and sensitively, respecting the natural and cultural context of the region.

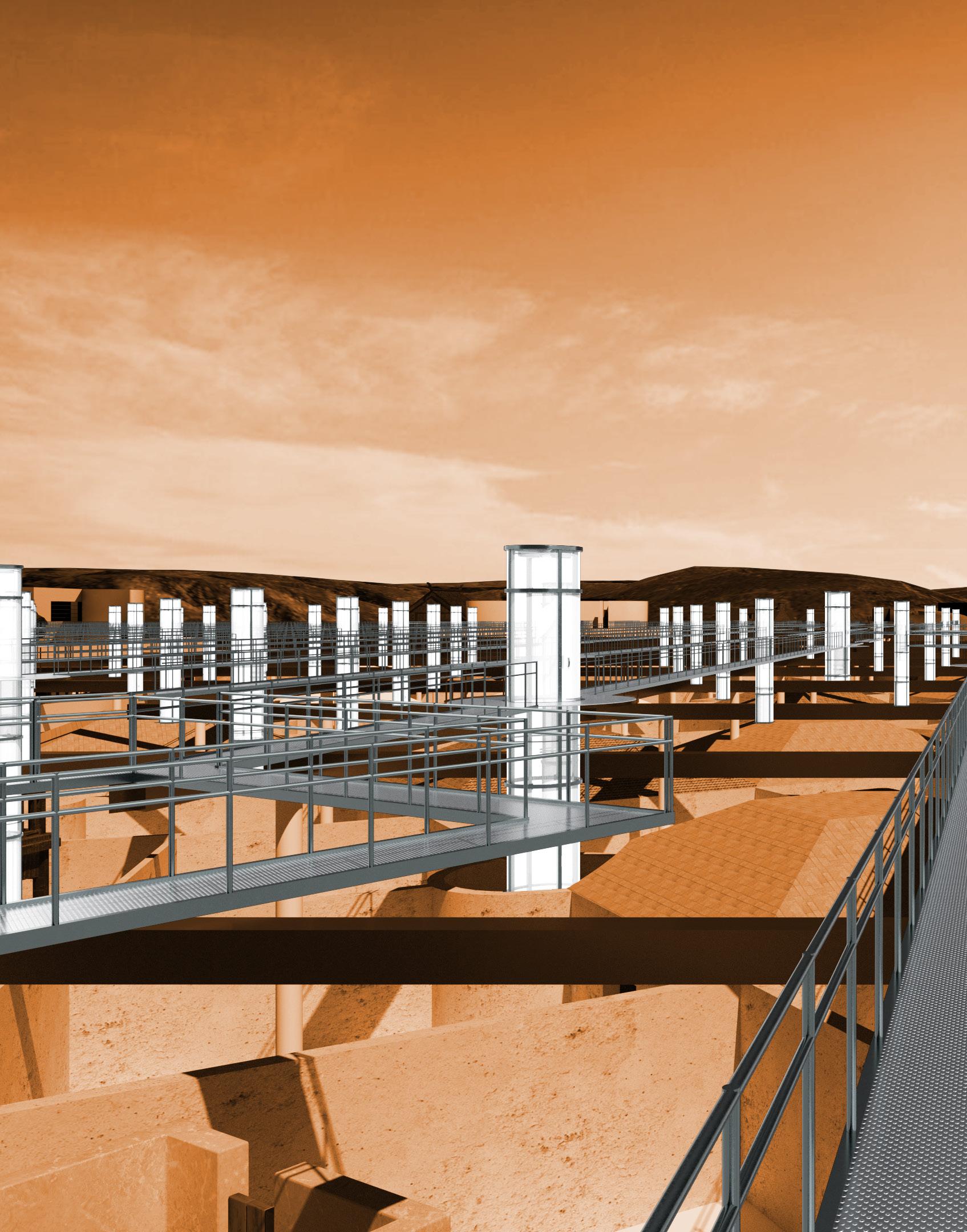

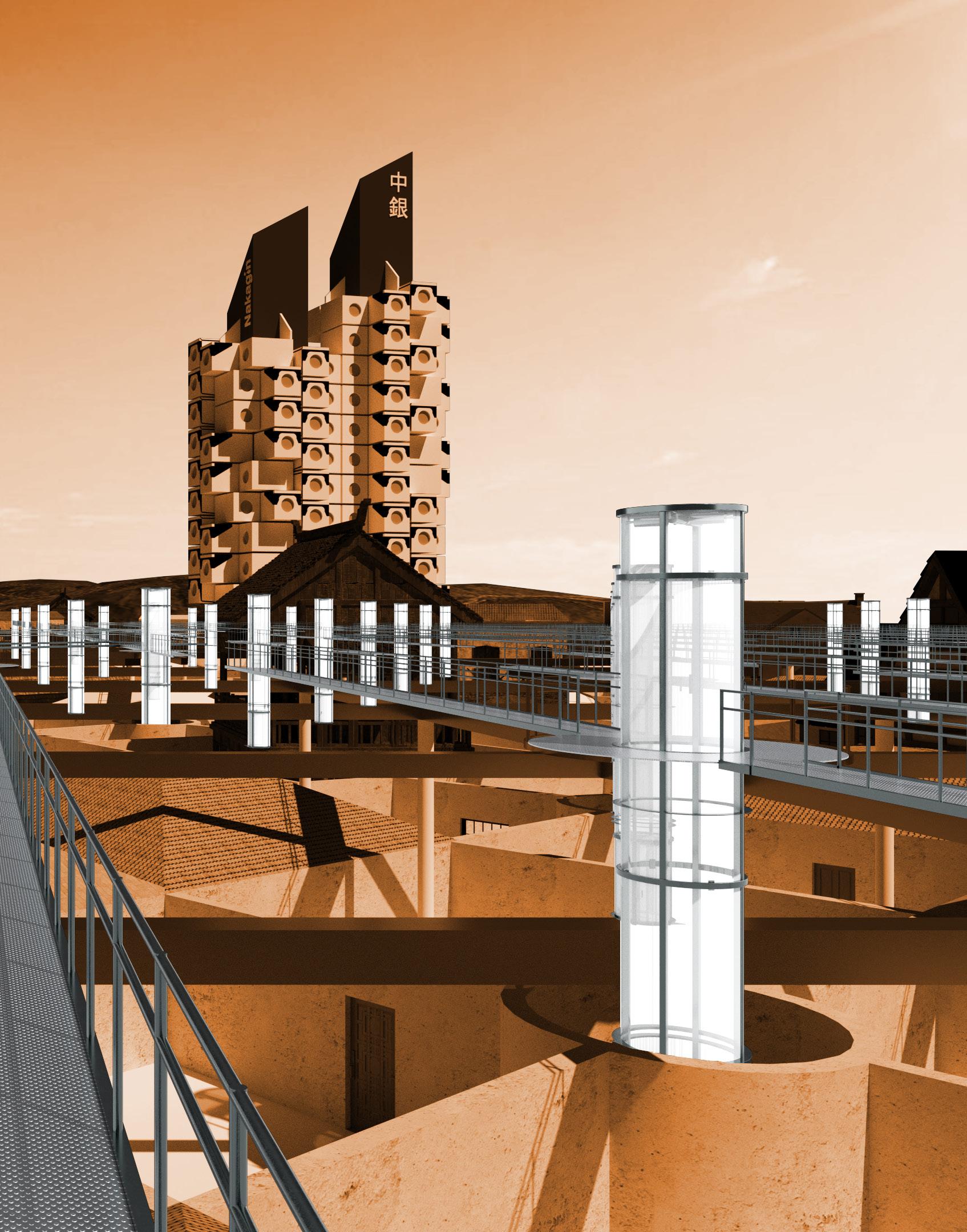

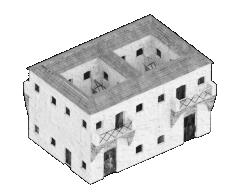

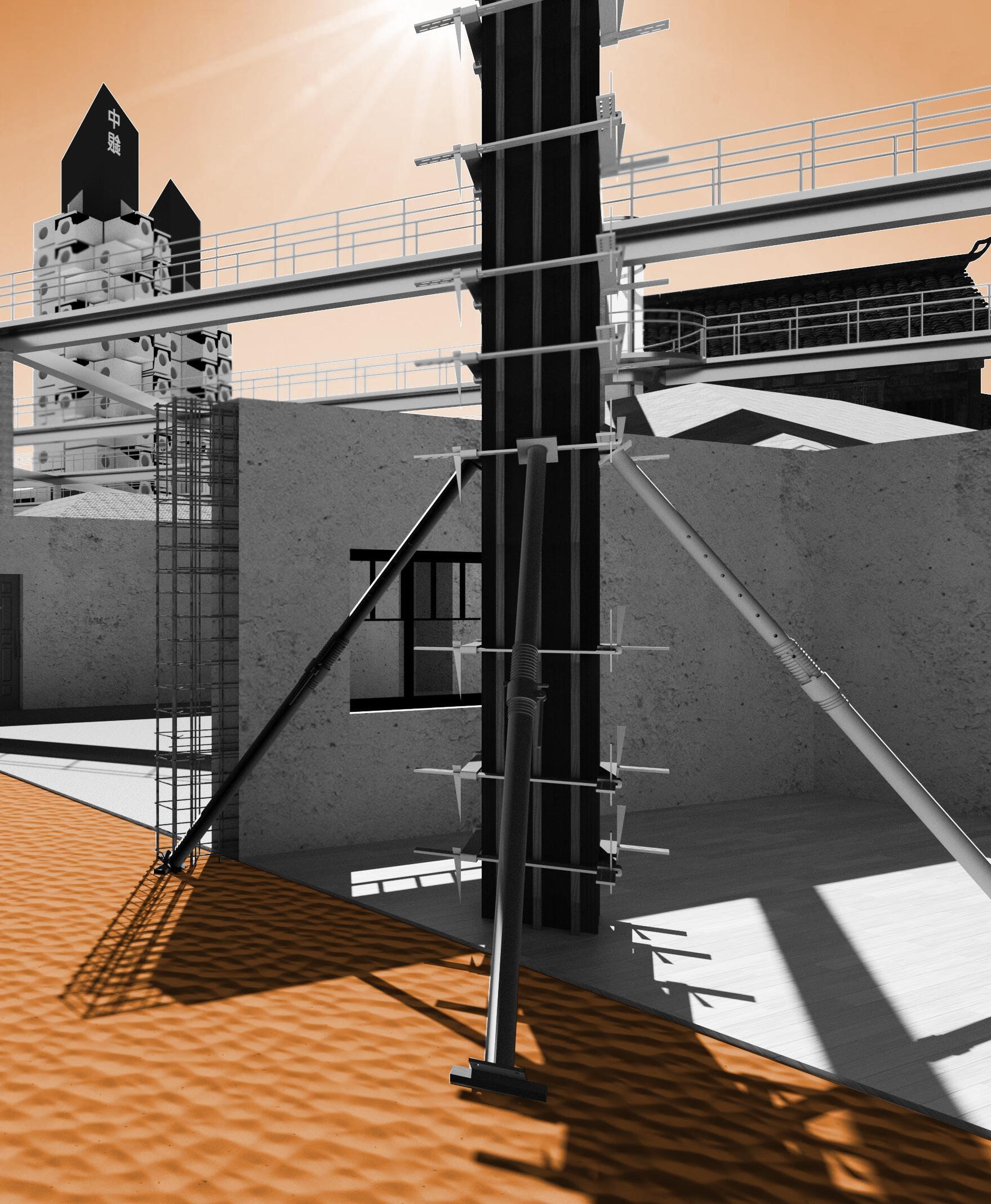

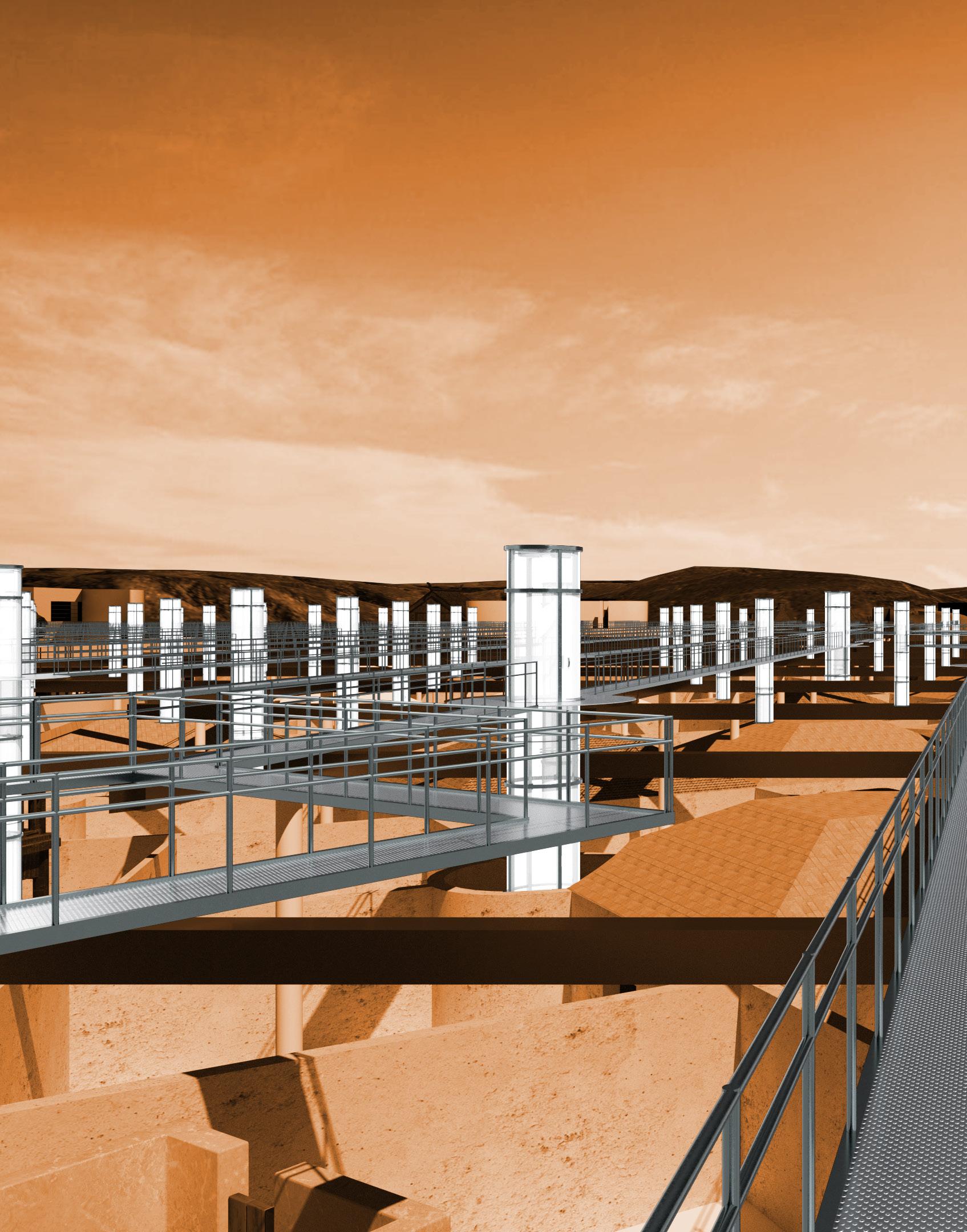

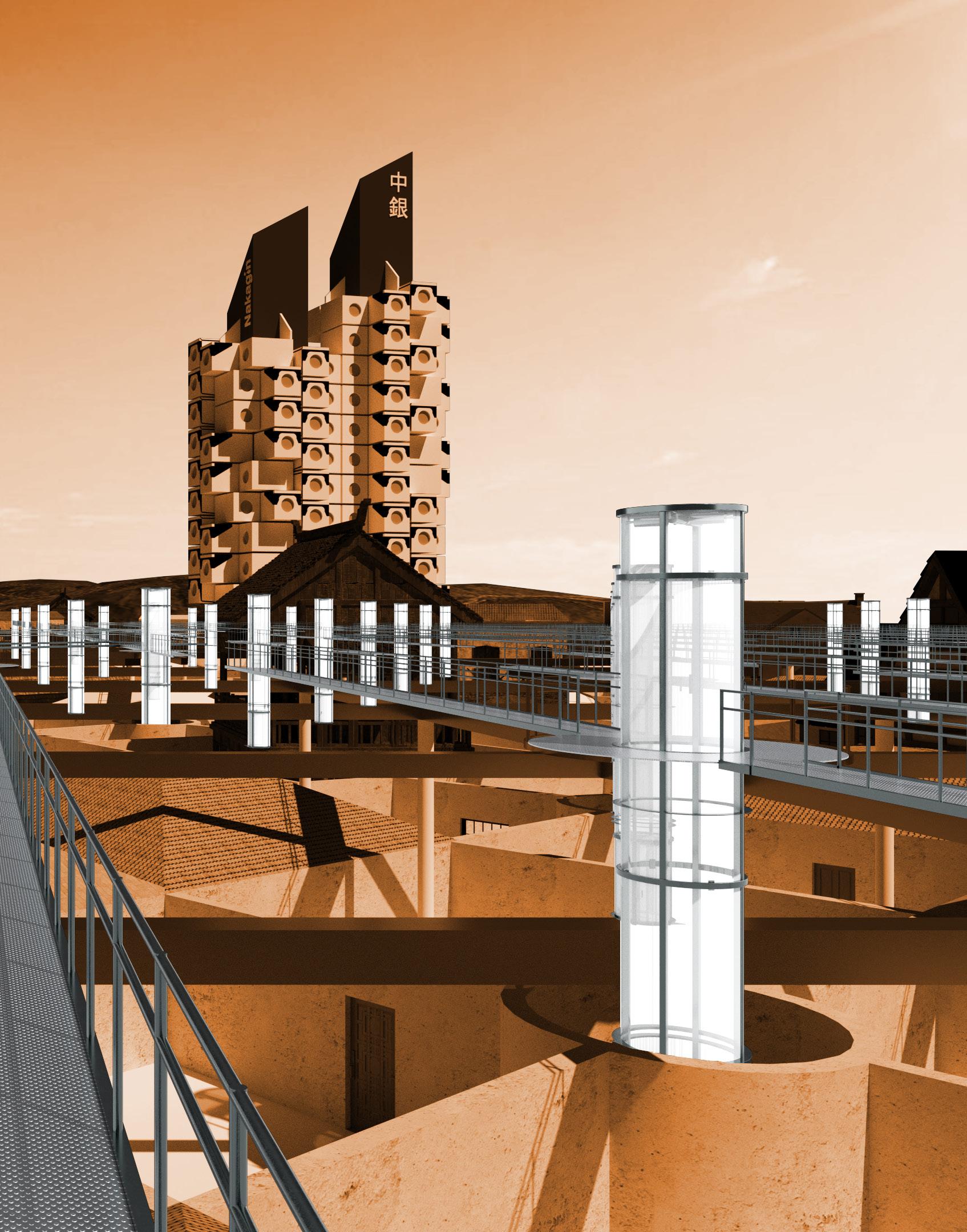

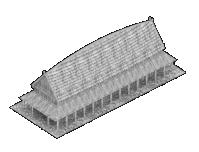

The town’s historic architecture, characterized by its red mud-brick constructions arranged in a chaotic grid, and its fluctuating rooflines, also inspire the design of the archive’s framework. The series of overlapping column and wall grids draw heavy inspiration from photos of Agadez.

Moreover, the integration of Agadez’s architectural style into the archive’s design not only helps the structure to blend with its cultural landscape but also pays homage to the local building traditions, making the archive a natural extension of the region’s architectural heritage. This approach attempts to make the archive appear less alien, and instead contribute to the local context.

46

47

AGADEZ, NIGER

30 FT COLUMN GRID 48

WALLGRID 49

30FT

NODES — VERTICAL CIRCULATION 50

500,000 BC

500,000 BC

20,000 BC

2.5 MILLION BC

10,000 BC

TUNNELS CONNECT NODES AND ORGANIZE ARCHIVE CHRONOLOGICALLY

20,000 BC

51

1,000 BC

2,000 BC

1,500 BC

2,500

500

1 AD 52

BC

LANDMARKS — MILESTONES IN THE EVOLUTION OF SHELTER RECONSTRUCTIONS OF MAJOR BUILDINGS AT TIME OF COMPLETION 2,500 BC 53

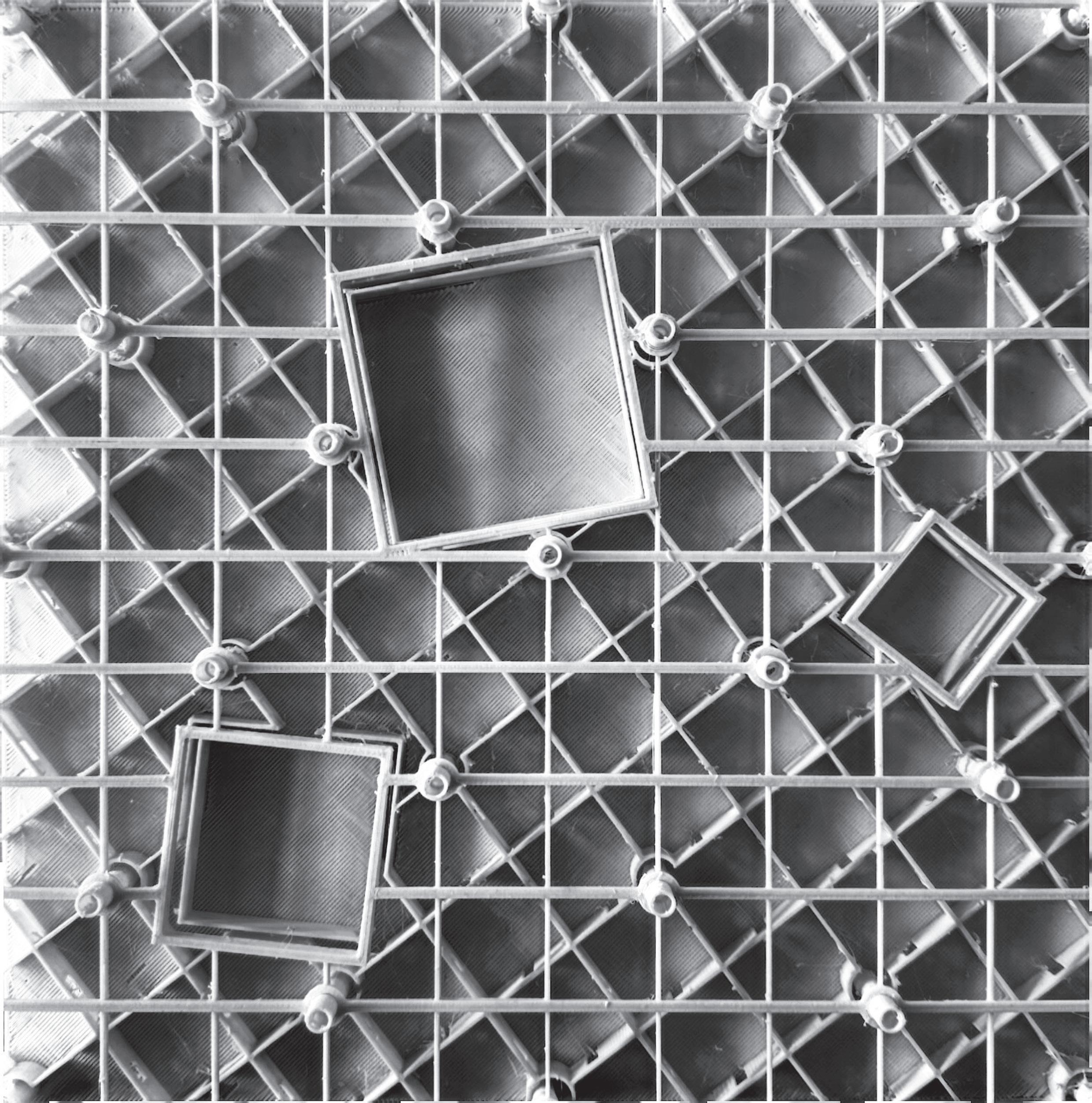

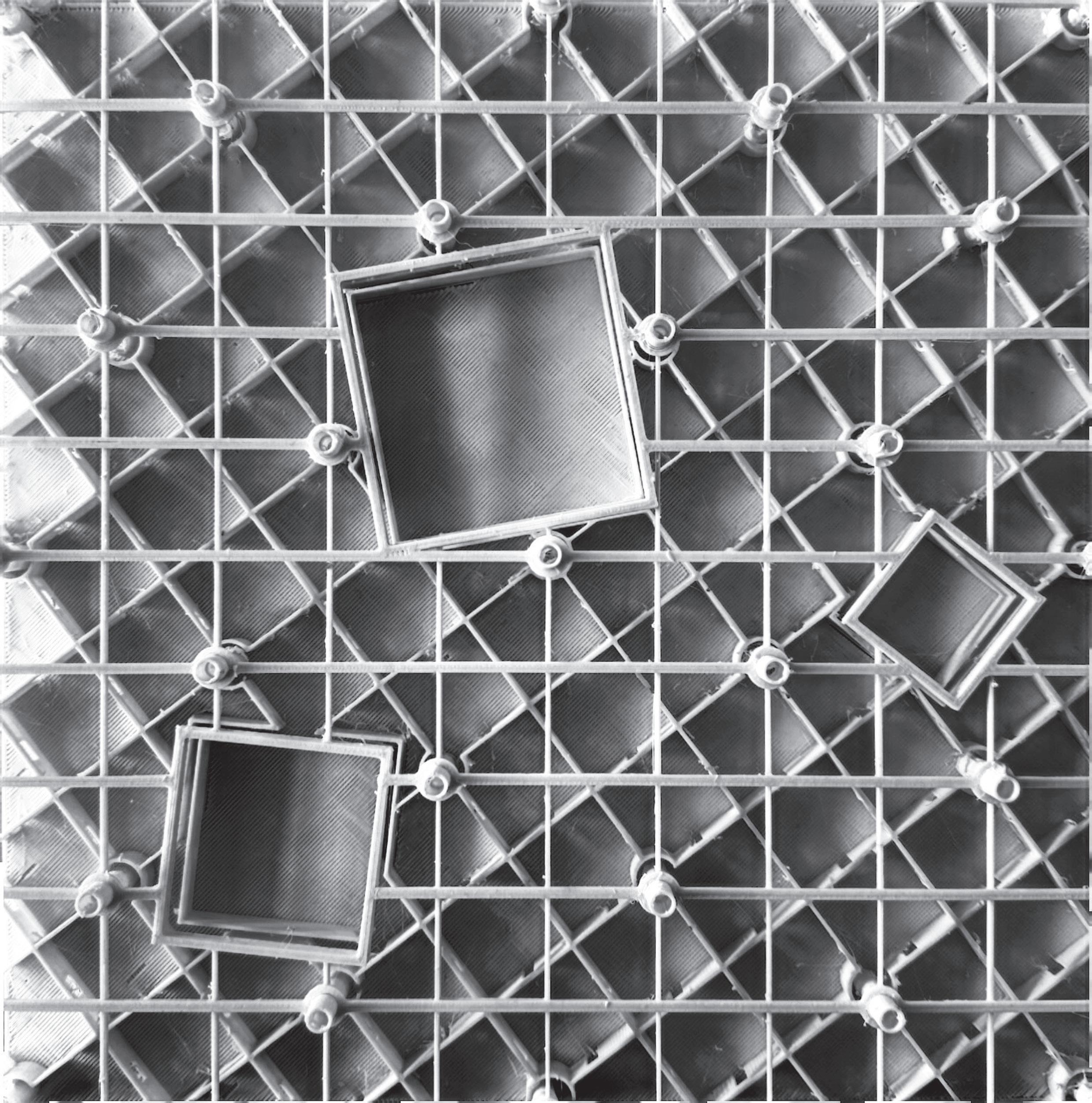

54 ELEMENTS AND LANDMARKS ARE ASSIGNED REFERENCE NUMBERS...

55 DOOR AND

ARE METICULOUSLY CATALOGED IN A CENTRAL REPOSITORY

ROOFED ROOMS SPACED BETWEEN NODES — TEMP/MOISTURE CONTROL & MAINTENANCE WORKSHOP

THUS BEGINS A FRAMEWORK FOR CONTINUOUS EXPANSION

58

59

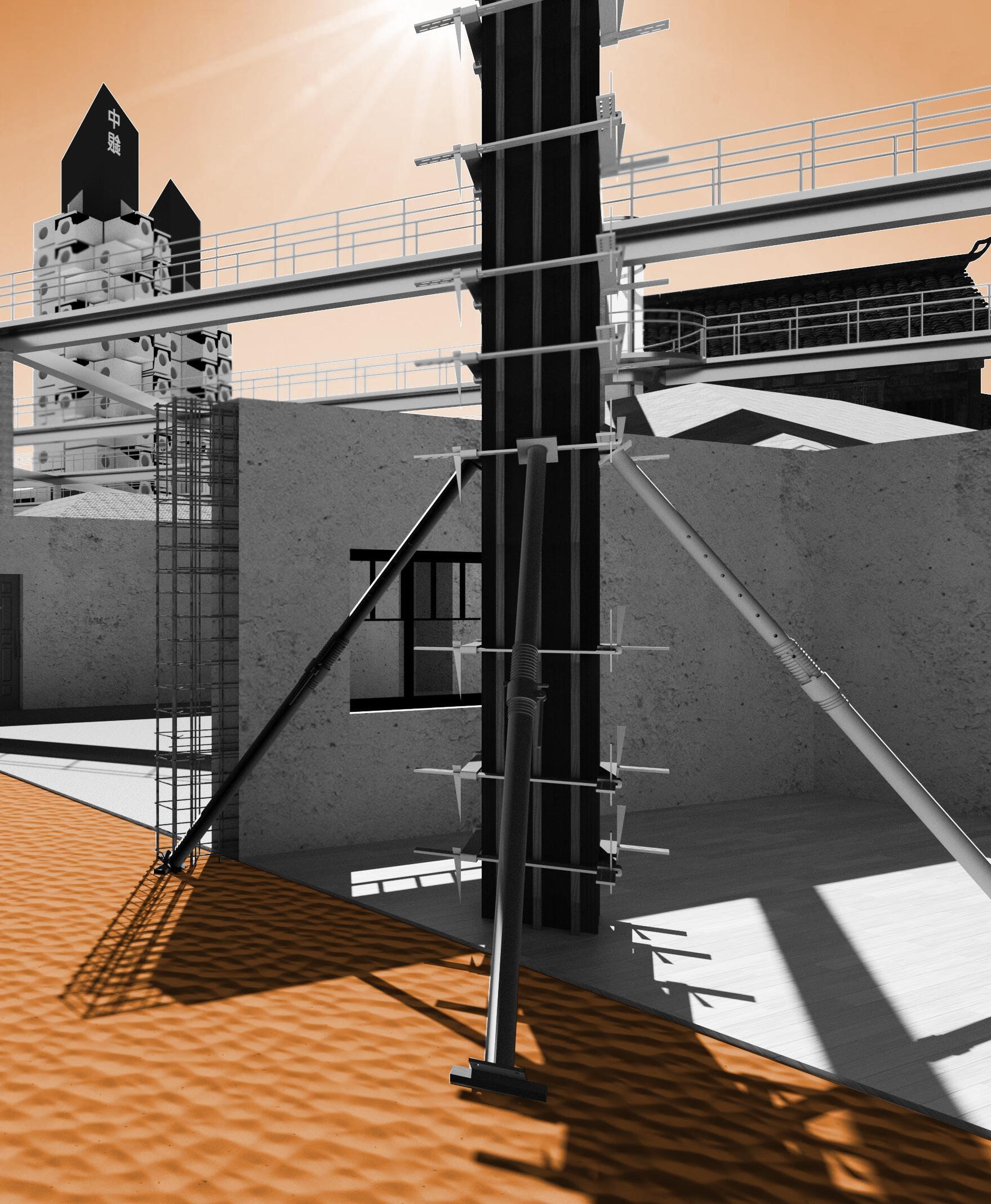

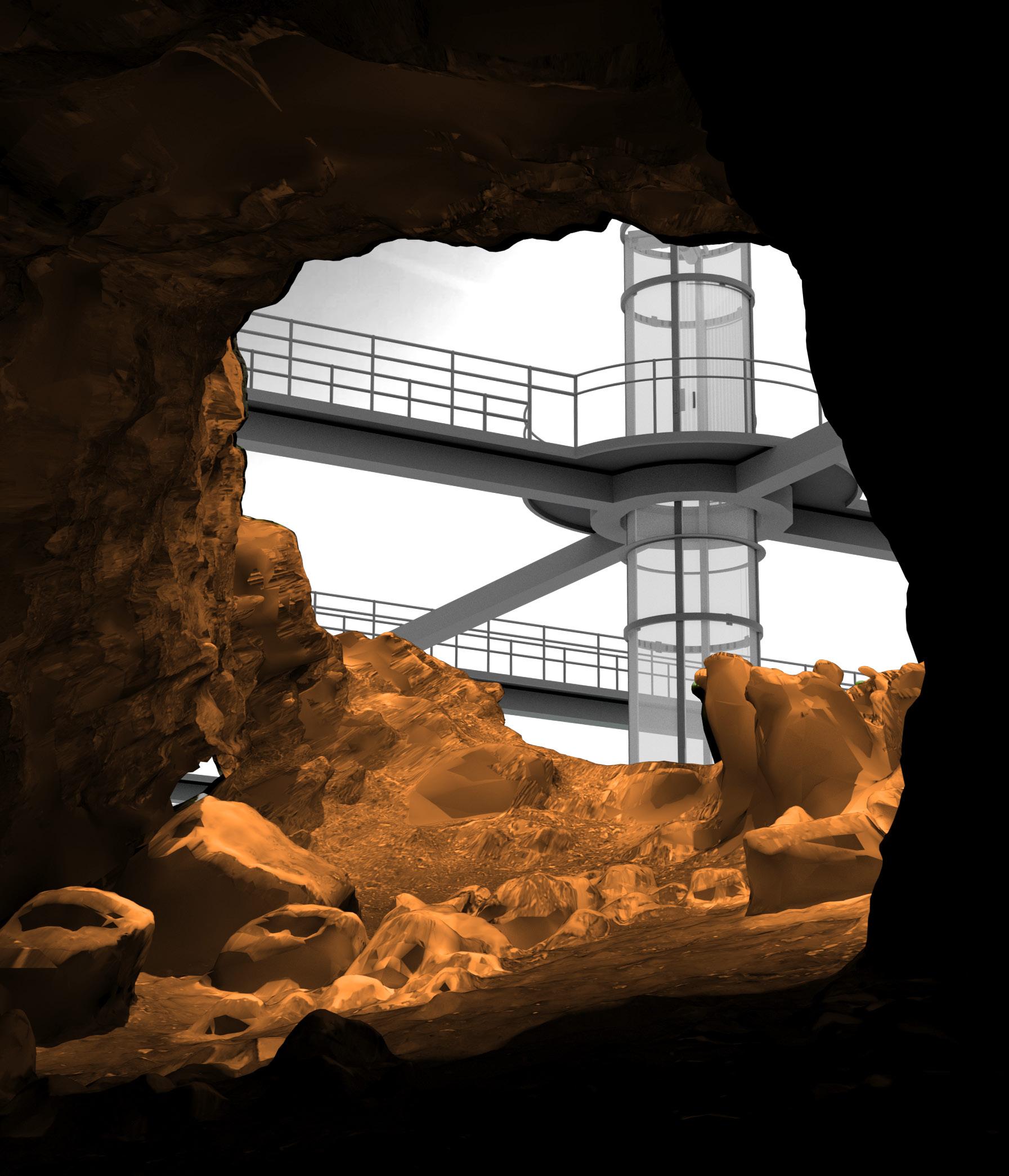

YEAR 2524...

60

high

From

above, the archive emerges,

its sprawling, structured framework contrasting starkly with the undisturbed sands of the Tenere.

61

Standing at the edge of the archive from the untouched expanse of the desert,

62

scaffolding climbs upwards and exposed rebar hints at future expansion.

63

64 After ascending the scaffolding, on the catwalk there unfolds a panoramic view over the endless archive.

The framework merges with distinct landmarks, arrayed like jewels across the structured expanse below.

65

Descending the elevator, space opens up to reveal a wigwam landmark from ~7000 BC.

66

It stands prominently among a framework of diverse architectural elements from the same time period.

67

Meandering the archive leads to a section resplendent with the rich heritage of Ancient Greece,

68

where towering Corinthian columns rise above intricate mosaic floors, detailing stories of a bygone era.

69

A roofed room maintains ideal temperature and humidity to preserve delicate architectural elements.

70

Here the Guardians of the Archive work diligently to maintain, expand, and protect this sacred place.

71

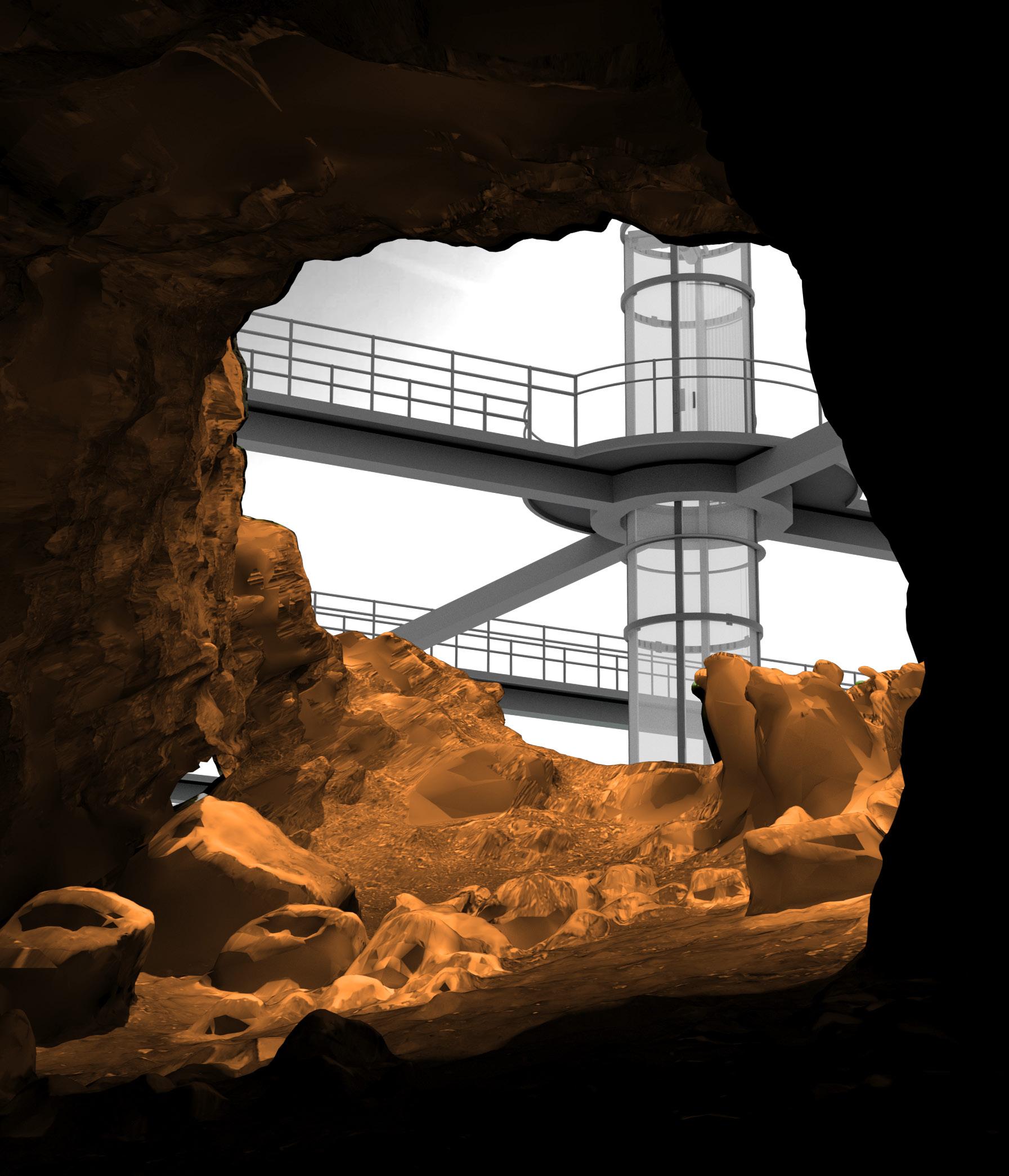

Taking elevators down, a light further down the tunnel becomes a portal from one landmark to the next.

72

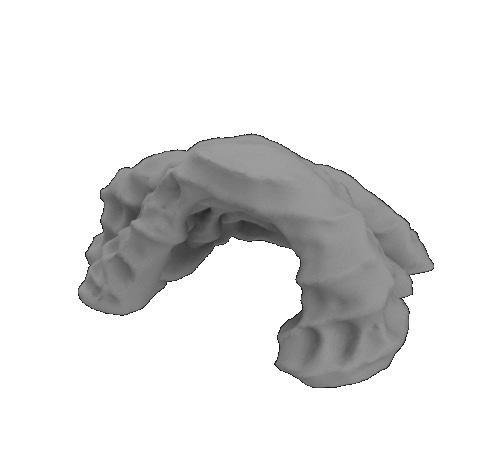

Through one tunnel, the wanderer emerges from the cave at the center of the archive, back to nature and back to the origin point of shelter

73

APPENDIX I FINAL REVIEW PRESENTATION

74

CAVE ~ 2.3 MILLION BC LANDMARK PREHISTORIC TERRA AMATA, ~ 400,000

~ 14,000

EUROPE ~ 7000 BC

LANDMARK 2924 LANDMARK 1

LANDMARK 150 JOMON PIT HOUSE, JAPAN

BC NEOLITHIC LONGHOUSE

ROMAN INSULA ANCIENT ROME 1ST C. BC

LANDMARK 15389

CHINESE HOUSE 5th C

1103

WIGWAM ~ 7,000 BC

LANDMARK 49674

FARNSWORTH HOUSE PLANO, ILLINOIS 1951

75 LANDMARK 2 PREHISTORIC HUT AMATA, FRANCE

400,000 BC

LANDMARK

LANDMARK 5135

76

8ft. x 8ft. Final Presentation Board/Model - Mixed Media

77

78

79

80

81

APPENDIX II DESIGN PROCESS ARTIFACTS

82

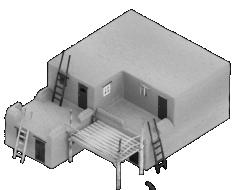

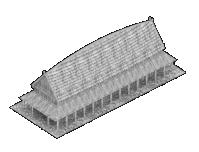

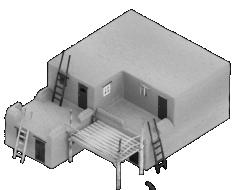

Early axon chunk of the archive

of ways to link nodes together

83

Diagram

84 Midreview chunk model

Early abstractions of organizing the archive through ‘nested’

85 FrenchWindow WindowPush-Out BayWindow FrenchDoor SlidingDoor SwingingDoor DutchDoor PivotDoor BarnDoor InteriorDoors EntryDoors SlidingWindows CasementWindows Windows Doors Single-Hung Double-Hung Horizontal Aperture

conditions

Diagram based on the Phylogeny: Protection from elements -> “Covering”

86

Cave Flat Angle

Dome Tree

Gable

Curve

Diagram based on the Phylogeny: Protection from elements -> “Enclosure”

87

Cave

Orthogonal

Angle

Shrub

APPENDIX III: THE PHYLOGENY

The initial [impossible] attempt based on “Shelter’s Hierarchy of Needs” at organizing all terminology related to architec ture and shelter in the hope of curating the fundamental architectural elements to be included in the archive.

SHELTER

● Protection from Elements

○ Covering

■ Roofing

● Pitched Roof

○ Gable Roof

○ Hipped Roof

○ Mansard Roof

● Flat Roof

○ Green Roof

○ Solar Roof

○ Butterfly Roof

● Canopy

○ Shade Sail

■ Tensile Fabric Structure

■ Retractable Shade Sail

○ Awnings

■ Fixed Awning

■ Motorized Awning

■ Portable Awning

○ Shading

■ Louvered Shading

● Adjustable Louvers

● Fixed Louvers

● Horizontal Louvers

■ Plant-Based Shading

● Pergola with Vines

● Living Wall

● Green Screens

■ Automated Shading

● Smart Blinds

● Motorized Curtains

● Sun-tracking Systems

○ Enclosure

■ Walls

● Exterior Walls

○ Cladding Materials

■ Brick Facade

■ Stone Veneer

■ Metal Panels

■ Insulated Wall Systems

● EIFS (Exterior Insulation and Finish System)

● SIPs (Structural Insulated Panels)

● Curtain Wall

● Interior Walls

○ Partition Walls

■ Demountable Partitions

■ Sliding Partitions

■ Folding Partitions

○ Feature Walls

■ Accent Wall

■ Textured Wall

■ Gallery Wall

● Safety and Security

○ Structure

■ Foundation

● Shallow Foundation

○ Slab Foundation

○ Strip Foundation

○ Mat Foundation

● Deep Foundation

○ Pile Foundation

○ Pier Foundation

■ Frame

○ Caisson Foundation

● Timber Frame

○ Post-and-Beam

○ Timber-Frame Construction

○ Log Construction

● Steel Frame

○ Steel Skeleton Frame

○ Steel Stud Frame

○ Light-Gauge Steel Frame

● Reinforced Concrete Frame

○ Cast-in-Place Concrete Frame

○ Precast Concrete Frame

○ Tilt-up Construction

■ Load-Bearing Elements

● Columns

○ Classical Columns

■ Doric Columns

■ Ionic Columns

■ Corinthian Columns

○ Modern Columns

■ Fluted Columns

■ Round Columns

■ Square Columns

● Beams

○ Beam Types

■ I-Beam

■ T-Beam

■ L-Beam

○ Composite Beams

■ Reinforced Concrete Beams

■ Steel and Concrete Composite Beams

■ Glulam Beams

● Structural Systems

○ Trusses

■ Pratt Truss

■ Warren Truss

■ Howe Truss

■ Fink Truss

■ Bowstring Truss

■ King Post Truss

○ Cantilever

■ Cantilevered Slab

■ Cantilevered Beam

■ Cantilevered Balcony

○ Arch

■ Roman Arch

■ Gothic Arch

■ Parabolic Arch

■ Catenary Arch

○ Aperture

■ Openings

● Windows

○ Picture Windows

○ Jalousie Windows

○ Clerestory Windows

○ Casement Windows

■ Bay Casement Windows

■ Push-out Casement Windows

■ French Casement Windows

○ Sliding Windows

■ Single-Hung Sliding Windows

■ Double-Hung Sliding Windows

■ Horizontal Sliding Windows

○ Bay Windows

■ Oriel Windows

■ Bow Windows

■ Box Bay Windows

○ Skylights

■ Fixed Skylights

■ Tubular Skylights

■ Vented Skylights

● Doors

○ Entry Doors

■ Swinging Doors

■ Pivot Doors

■ Dutch Doors

■ Arched Doors

■ Revolving Doors

■ Garage Doors

○ Interior Doors

■ French Doors

■ Barn Doors

■ Sliding Doors

■ Pocket Sliding Doors

■ Bi-fold Sliding Doors

■ Multi-panel Sliding Doors

■ Folding Doors

■ Security Features

● Locks

○ Mortise Locks

○ Cylinder Locks

○ Smart Locks

● Bars

○ Window Bars

○ Door Bars

● Shutters

○ Bahama Shutters

○ Colonial Shutters

○ Rolling Shutters

○ Thermal Regulation

■ Insulation

● Fiberglass Insulation

○ Batts and Rolls

○ Loose-fill Insulation

○ Rigid Panels

● Foam Board Insulation

○ Expanded Polystyrene (EPS)

○ Extruded Polystyrene (XPS)

○ Polyisocyanurate (Polyiso)

● Cellulose Insulation

○ Blown-in Cellulose

○ Dense-packed Cellulose

○ Wet-spray Cellulose

■ Ventilation

● Natural Ventilation

○ Operable Windows

○ Ventilation Louvers

○ Stack Effect

● Mechanical Ventilation

○ Ventilation Fans

○ Exhaust Systems

○ Air Handling Units

● Cross Ventilation

○ Building Orientation

○ Windcatchers

○ Atriums for Ventilation

■ Climate Control

● Heating

○ Radiant Heating

■ Underfloor Heating

■ Radiant Ceiling Panels

○ Forced Air Heating

■ Furnace

■ Heat Pump

■ Central Heating

○ Geothermal Heating

■ Ground Source Heat Pump

■ Geothermal Radiant Heating

■ Geothermal Heat Exchanger

● Cooling

○ Air Conditioning

■ Central Air Conditioning

■ Split System Air Conditioning

■ Ductless Mini-split

○ Evaporative Cooling

■ Swamp Coolers

■ Ventilation Cooling

○ Passive Cooling

■ Thermal Mass

■ Night Ventilation

○ Air Circulation

■ Ceiling Fans

■ Attic Fans

■ Exhaust Fans

● Comfort

○ Lighting

■ Fixtures

■ Whole-House Fans

● Chandeliers

● Pendant Lights

● Sconces

● Track Lighting

● Recessed Lights

■ Lamps

● Floor Lamps

● Table Lamps

● Desk Lamps

● Accent Lamps

● Task Lamps

○ Personal Space

■ Bedrooms

● Master Bedroom

● Guest Bedroom

● Children’s Bedroom

■ Bathrooms

● Master Bathroom

○ Walk-in Shower

○ Soaking Tub

○ Double Vanity

● Guest Bathroom

● Powder Room

○ Pedestal Sink

○ Wall-Mounted Vanity

○ Floating Vanity

■ Studies

● Home Office

○ Built-in Desk

○ Ergonomic Furniture

○ Task Lighting

● Library

○ Bookshelves

○ Reading Nook

○ Study Desk

■ Closets

● Walk-in Closet

○ Closet Organizer

○ Shoe Rack

○ Dressing Area

● Reach-in Closet

○ Sliding Doors

○ Built-in Drawers

○ Hanging Rods

● Wardrobe

○ Freestanding Wardrobe

○ Armoire

○ Wardrobe Cabinet

● Social Spaces

○ Rooms

■ Living Room

● Family Room

● Great Room

● Sunroom

■ Dining Room

● Formal Dining Room

○ Dining Table

○ Dining Chairs

● Casual Dining Area

■ Kitchen

● Kitchen Layouts

○ L-Shaped Kitchen

○ U-Shaped Kitchen

○ Galley Kitchen

○ Island Kitchen

○ Peninsula Kitchen

■ Recreation Room

● Game Room

○ Billiards Table

○ Arcade Games

○ Home Bar

● Home Theater

○ Media Room

○ Soundproofing

○ Theater Seating

● Gym

○ Home Gym Equipment

○ Mirrors

○ Rubber Flooring

○ Fitness Technology

○ Common Areas

■ Hallways

■ Foyers

■ Courtyards

● Central Courtyard

○ Water Feature

○ Outdoor Seating

○ Garden Planters

● Enclosed Courtyard

○ Privacy Walls

○ Trellises

○ Fire Pit

■ Terraces

● Rooftop Terrace

○ Decking

○ Green Roof

○ Outdoor Furniture

● Garden Terrace

○ Raised Planters

○ Paving Stones

○ Garden Seating

● Balcony Terrace

○ Railing Design

○ Privacy Screens

○ Small-Scale Furniture

■ Patios

● Paver Patio

○ Hardscape Design

○ Retaining Walls

○ Outdoor Lighting

● Stone Patio

○ Flagstone

○ Pavers

○ Patio Cover

● Concrete Patio

● Expression

○ Ornamentation

■ Decorative Elements

● Molding

○ Crown Molding

○ Dentil Molding

○ Cove Molding

○ Egg-and-Dart Molding

○ Baseboard Molding

○ Base Shoe Molding

○ Quarter Round Molding

○ Colonial Baseboard

○ Chair Rail Molding

○ Wainscoting

○ Picture Rail

○ Panel Molding

○ Ogee Molding

○ Rope Molding

○ Bead Molding

○ Leaf Molding

○ Dentil Block Molding

○ Greek Key Molding

○ Gothic Molding

○ Shell Molding

○ Astragal Molding

○ Band Molding

○ Dental Molding

● Carvings

○ Wood Carvings

■ Fretwork

■ Wood Appliques

■ Rosettes

■ Scrollwork

■ Acanthus Leaf

■ Scrolls

■ Swags

■ Shells

■ Vine Motif

■ Grapevine Carving

■ Fluting

■ Reeding

■ Fluted Columns

■ Cigar Store Indian

■ Totem Pole

■ Wood Sculptures

○ Stone Carvings

■ Gargoyles

■ Grotesques

■ Bas-relief

■ Statues

■ Medallions

■ Keystones

○ Plaster Carvings

■ Stucco Embellishments

■ Plaster Corbels

■ Ceiling Medallions

■ Plaster Moldings

■ Rosettes

■ Swags

● Metal Carvings

○ Wrought Iron

■ Wrought Iron Gates

■ Wrought Iron Railings

■ Wrought Iron Balusters

■ Wrought Iron Panels

■ Wrought Iron Decor

○ Cast Iron

■ Cast Iron Fencing

■ Cast Iron Grilles

■ Cast Iron Columns

■ Cast Iron Facades

○ Bronze

■ Bronze Sculptures

■ Bronze Plaques

■ Bronze Reliefs

■ Bronze Ornaments

○ Copper

■ Copper Gargoyles

■ Copper Weathervanes

■ Copper Ornaments

○ Brass

■ Brass Inlays

■ Brass Ornaments

■ Brass Hardware

● Stonework

○ Stone Inlays

○ Stone Reliefs

○ Stone Medallions

○ Stone Frieze

○ Stone Tracery

○ Stone Rosettes

○ Stone Ornaments

● Tilework

○ Ceramic Tiles

○ Porcelain Tiles

○ Mosaic Tiles

○ Terracotta Tiles

○ Subway Tiles

○ Art Nouveau Tiles

○ Moroccan Tiles

○ Spanish Tiles

● Glasswork

○ Stained Glass

○ Leaded Glass

○ Beveled Glass

○ Etched Glass

○ Glass Mosaics

● Metalwork

○ Metal Inlays

○ Metal Panels

○ Metal Screens

○ Metal Grilles

○ Metal Balusters

○ Metal Ornaments

○ Ironwork

■ Decorative Ironwork

■ Iron Gates

■ Iron Railings

■ Iron Balconies

■ Iron Fencing

○ Brasswork

■ Brass Inlays

■ Brass Ornaments

■ Brass Hardware

○ Copperwork

■ Copper Ornaments

■ Copper Grilles

■ Copper Weathervanes

○ Bronze Work

■ Bronze Ornaments

■ Bronze Plaques

■ Bronze Reliefs

○ Metal Facades

■ Metal Cladding

■ Perforated Metal Panels

■ Corrugated Metal

● Plasterwork

○ Plaster Moldings

○ Plaster Panels

○ Plaster Ornaments

○ Plaster Columns

○ Plaster Medallions

● Frescoes

○ Fresco Painting

■ True Fresco

■ Buon Fresco

■ Secco Fresco

■ Digital Frescoes

■ Digital Projection Frescoes

■ LED Fresco Lighting

■ Interactive Frescoes

■ Trompe-l’oeil Frescoes

■ Illusionistic Frescoes

■ Architectural Trompe-l’oeil

■ Still Life Trompe-l’oeil

● Sculptures

○ Indoor Sculptures

■ Abstract Sculptures

■ Figurative Sculptures

■ Installation Art

○ Outdoor Sculptures

■ Land Art

■ Kinetic Sculptures

■ Environmental Sculptures

● Roof Ornamentation

○ Cupolas

○ Spires

○ Finials

○ Weathervanes

○ Crestings

○ Roof Pinnacles

○ Turrets

○ Roof Balustrades

○ Roof Lanterns

○ Roof Ornaments

○ Roof Sculptures

● Facade Decor

○ Façade Sculptures

○ Façade Reliefs

○ Façade Medallions

○ Façade Plaques

○ Façade Niches

○ Façade Grilles

○ Façade Balconies

○ Façade Corbels

○ Façade Statues

○ Façade Ornaments

○ Façade Capitals

○ Façade Cartouches

● Interior Decor

○ Ceiling Decor

■ Ceiling Medallions

■ Ceiling Domes

■ Ceiling Rosettes

■ Ceiling Murals

■ Coffered Ceilings

○ Wall Decor

■ Wall Panels

■ Wall Reliefs

■ Wall Niches

■ Wall Ornaments

■ Wall Murals

■ Wall Decals

■ Wall Tapestries

○ Fireplace Decor

■ Mantelpieces

■ Fireplace Surrounds

■ Overmantels

■ Fireplace Tiles

○ Floor Decor

■ Floor Medallions

■ Floor Inlays

■ Floor Mosaics

■ Parquet Flooring

■ Floor Borders

■ Terrazzo Flooring

○ Materials

■ Stone

● Marble

● Granite

● Limestone

● Sandstone

● Travertine

● Slate

● Alabaster

● Onyx

■ Wood

● Oak

● Maple

● Cherry

● Walnut

● Mahogany

● Pine

● Cedar

● Redwood

■ Metal

● Iron

● Brass

● Copper

● Bronze

● Aluminum

■ Glass

● Stainless Steel

● Stained Glass

● Leaded Glass

● Beveled Glass

● Etched Glass

■ Plaster

● Gypsum

● Lime Plaster

● Cement Plaster

■ Ceramic

● Porcelain

● Terracotta

■ Tile

● Ceramic Tiles

● Porcelain Tiles

● Mosaic Tiles

● Subway Tiles

■ Fabric

● Silk

● Velvet

● Brocade

● Tapestry

● Damask

● Linen

● Wool

■ Paper

● Wallpaper

● Papier-Mâché

● Decoupage

■ Composite Materials

● Fiberglass

● Resin

● Composite Panels

● Carbon Fiber

● Acrylic

■ Synthetic Materials

● Plastic

● Acrylic

● PVC

● Polystyrene

● Polyurethane

● Foam

● Fiberglass Reinforced Panels

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ss “Primitive Shelter ” Ekistics 13, no 78 (1962): 276–81

yrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings. Edited by Donald A. Yates York: New Directions Publishing, 1962

"Cultural Expressions of Medieval Societal Structures." European no 1 (1986): 45-59

k. A summary of recent work concerning architecture." Ed. B. Söğüt, ya: Ahmet Adil Tırpan Armağanı İstanbul (2012): 303-314

nts of Architecture. Rotterdam: Taschen, 2014.

y on Architecture ” London: T Osbourne and Shipton (1755)

a New Architecture Translated by Frederick Etchells London: 7

993) [1971] "Theory Z: The farther reaches of human nature ” New York:

ective Qualities of Crater Formations in Desert Environments " Journal of 9, no 2 (2005): 102-118

ction to Universal History London: Charles C Little and James Brown,

"Medieval Housing as a Cultural Expression " Scandinavian Journal of 155-175

with Nature: A Study in Ingenuity and Sustainability " Architectural Digest 1

logy and the Rise of the Networked City in Europe and America " 51, no 1 (2010): 34-58

n Nomadic Architecture: Space, Place and Gender Washington, D C : Press, 1995

servation in Arid Climates " Journal of Arid Environments 48, no 3 (2002):

a Translated by Morris Hicky Morgan Cambridge: Harvard University

mith, and Linda Johnson "Inca Masonry: A Study of Techniques and ncient Technologies 12, no 4 (2000): 55-77

Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum Princeton: Princeton

99

IMAGES

All images original unless noted here:

1 Antonio Toca Fernández in “La biblioteca de babel: una modesta propuesta” (79)

2 KennyOMG, Wikimedia Commons Accessed 5/10/2024

https://commons wikimedia org/wiki/File:Pyramids of the Giza Necropolis jpg

3 Courtesy of Svalbard Global Seed Vault Accessed 5/10/2024 https://www smithsonianmag com/smart-news/why-scientists-just-made-major-seed-bank-deposit -180962274/

4 Courtesy of Internet Archive Blogs Accessed 5/10/2024

https://blog.archive.org/2012/07/24/news-from-the-internet-archive-0002/

5 Courtesy of Smith Archive / Alamy Accessed 5/10/2024

https://www.livescience.com/archaeology/famous-neanderthal-flower-burial-debunked-because-p ollen-was-left-by-burrowing-bees

6. Laugier, M. A. “An Essay on Architecture.” London: T. Osbourne and Shipton. (1755).

7 Courtesy of Notre Dame OpenCourseWare Accessed 5/10/2024 https://primitivehutb5.blogspot.com/2012/12/the-primitive-hut-narrative-and-its.html

8 Christopher Rose, UNESCO Accessed 5/10/2024 https://whc unesco org/en/list/848/

9 Courtesy of De Agostini Picture Library / GettyImages Accessed 5/10/2024

https://www gettyimages com/detail/news-photo/the-city-of-catal-huyuk-with-its-one-room-houseswhich-were-news-photo/541323999

10 Courtesy of Google Earth

11 Courtesy of Meteorite Recon Accessed 5/10/2024

https://www meteorite-recon com/home/tenere/p4

100