Jordan Scheuermann

Writings + Robots

20 1920 21

20 1920 21

SPRING 2020

HT 2201

Instructed by John Cooper, Erik Gheniou, and Marcelyn Gow

Andrew Atwood discusses whether Ed Ruscha or Catherine Opie’s seemingly banal photography of Los Angeles streets better exemplifies the qualities Scott Brown found. Atwood explores how each photographer is able to capture Scott Bown’s Los Angeles through the subject matter, composition, and display of the photographs. However, technological changes over the past two decades have provided the opportunity to re-examine the “fragmentary and fleeting” qualities of the city . This paper investigates how Los Angeles

can be represented using contemporary tools and ideas of decentralization and the removal of established hierarchies found in both Los Angeles and Hiro Steryl’s concept of the “poor image”.

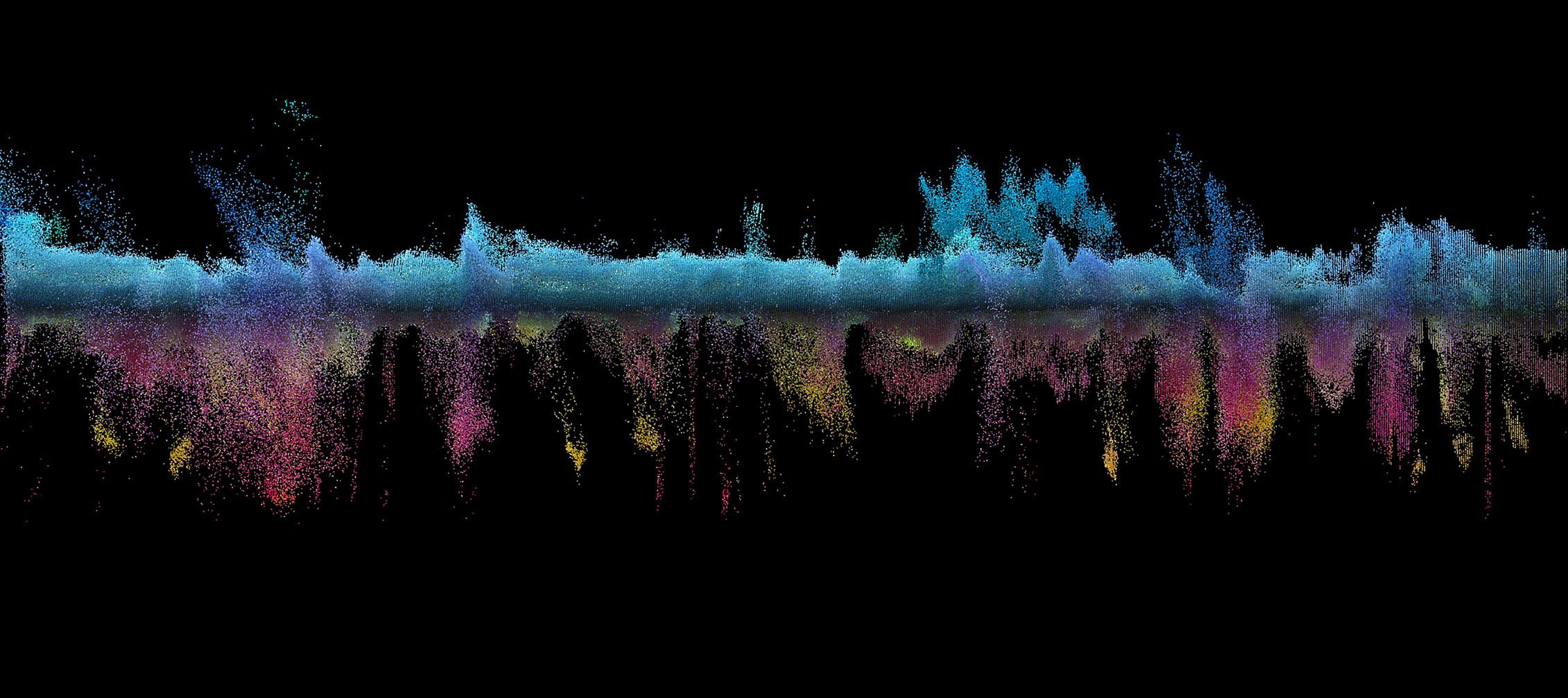

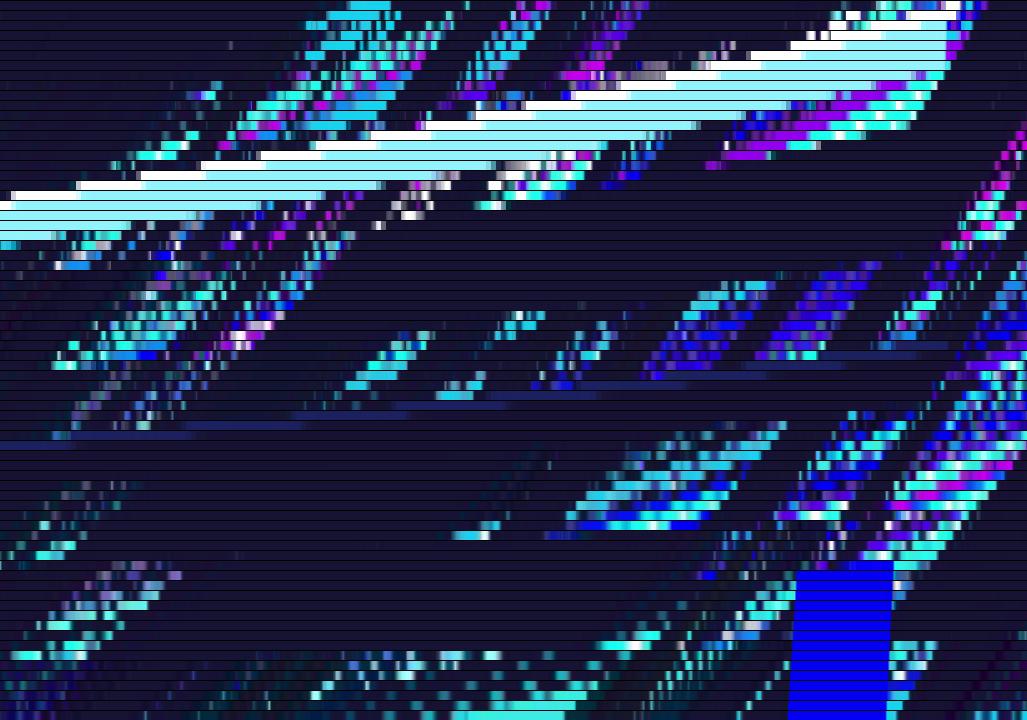

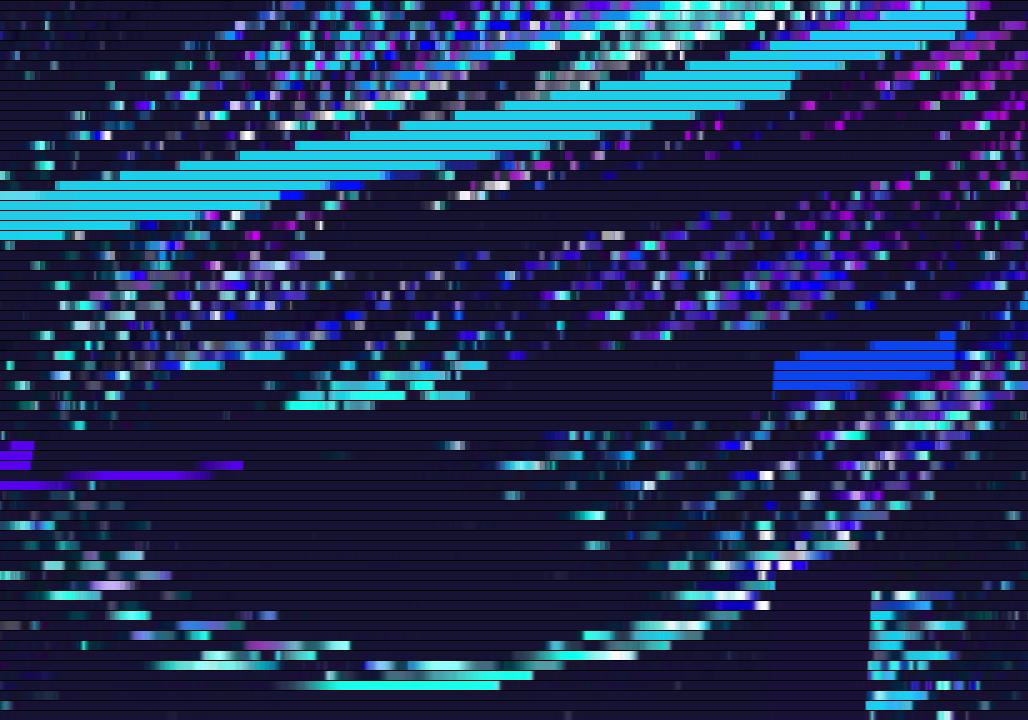

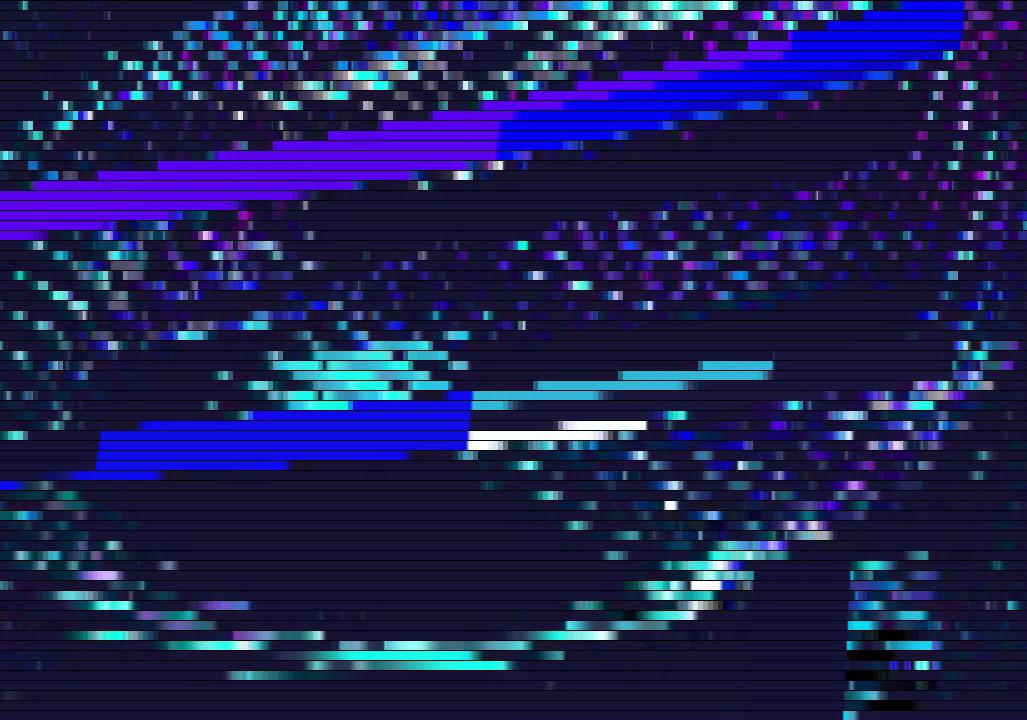

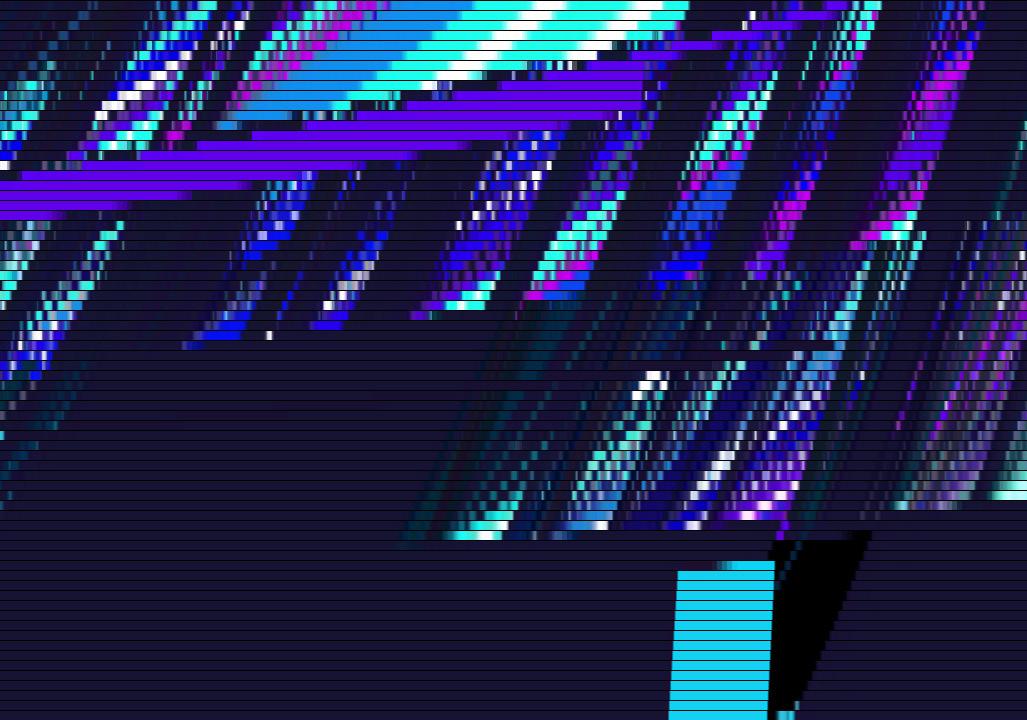

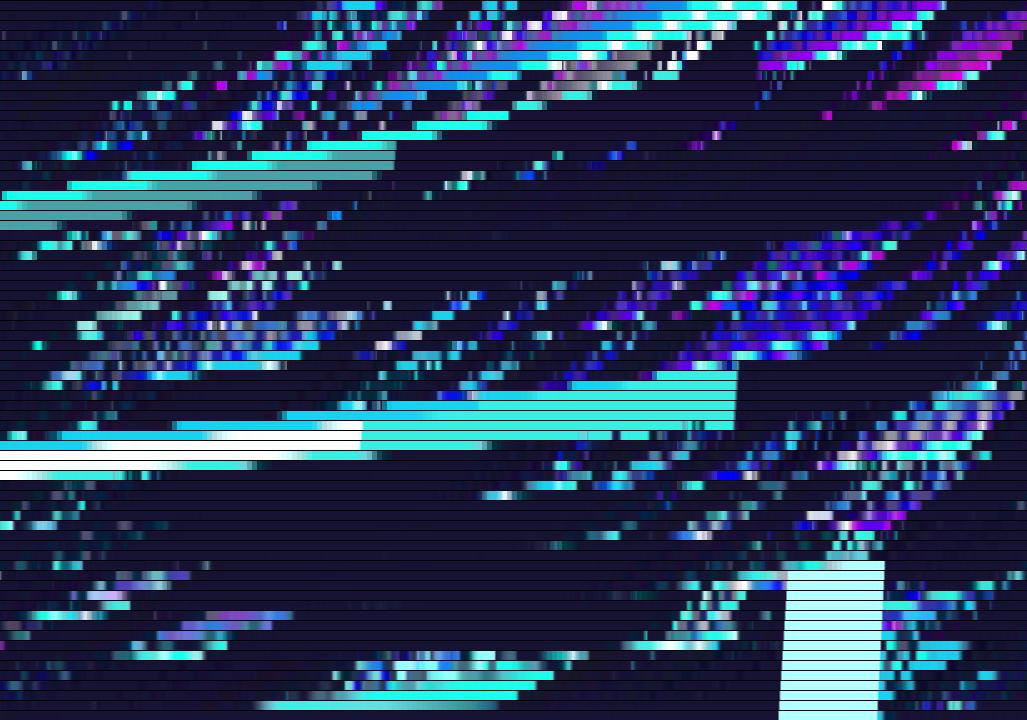

To do so, a video recording of Ed Ruscha’s subject matter, the Sunset Strip , was made and its quality degraded similar to Thomas Ruff’s Jpeg series

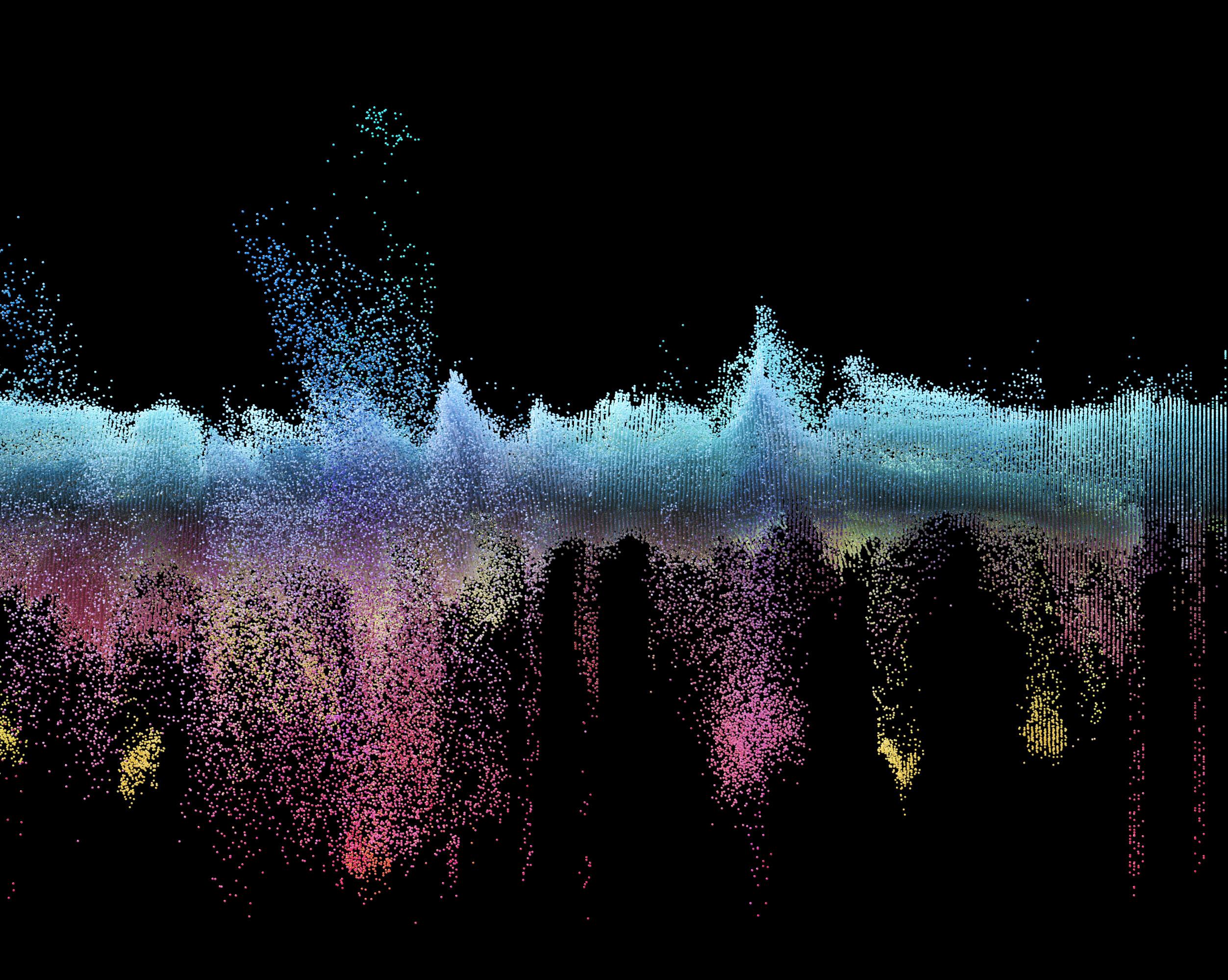

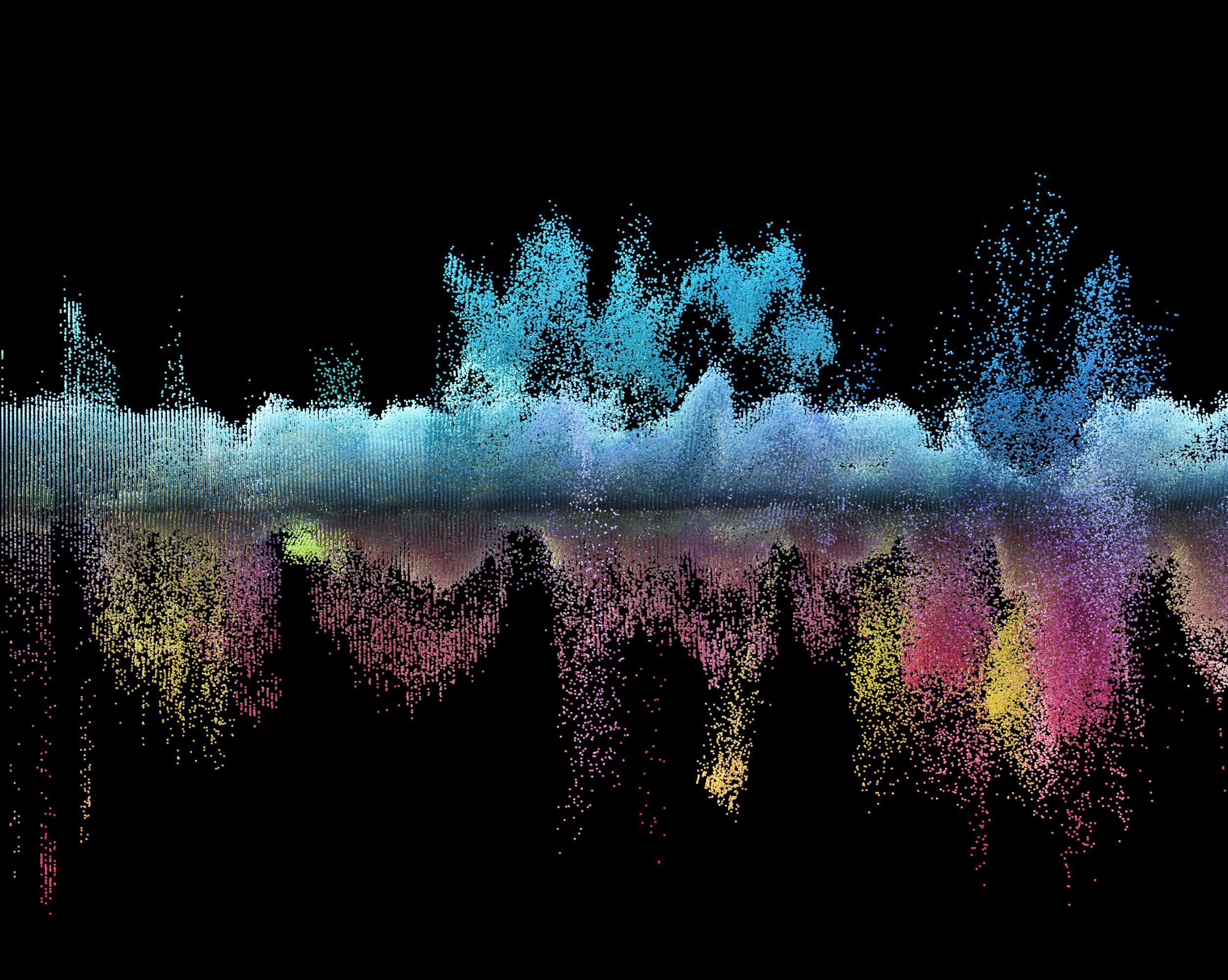

Individual pixels were extracted and re-mapped based on color data. The new low-resolution images started to resist the familiar immediacy of the highresolution video frames. A level

of fuzziness was introduced and the colors of the street scene became abstracted. New relationships between adjacent objects formed as their boundaries softened and became impossible to view an exact delineation between where one object ended and another started. As frames became stacked upon each other the ephemeral, fleeting images of the video can be seen directly next to each other as the dimension of time is mapped.

Andrew Atwood, in his book Not Interesting: On the Limits of Criticism in Architecture, explores Denise Scott Brown’s description of Los Angeles as “It’s the same even, open-ended system with multiple possibilities for the definition and redefinition of focus depending on where you’re at. Sometimes the yellows shine the brightest, sometimes the blues”. 1 For Scott Brown, Ed Ruscha’s photographs in Some Los Angeles Apartments and Every Building on the Sunset Strip encapsulate her description of Los Angeles because they are able to document the “fragmentary and fleeting” nature of the things themselves through mundane photographs. 2

However, for Atwood, it is not Ruscha who truly captures Denise Scott Brown’s description of Los Angeles. It is Catherine Opie through her Freeway and Mini-mall series.

Not so much by their content or how they are photographed, both Ruscha and Opie document mundane subjects photographed in mundane ways, but how Opie presents her work. Unlike Ruscha’s strictly linearly organized photographs in Every Building on the Sunset Strip in which the buildings appear in the same order as one would experience them driving down the street, Opie introduces uncertainty and arbitrariness. She titles her work with names such as Untitled #1 and displays them in seemingly random order. By doing so she is able to make “freewheeling connections between style and subject, between adjacent photographs, between the formal lines of nonneighboring freeways”. 3

Atwood is interested in these works because he sees them as successfully portraying what he describes as the boring mode of attention. For him, the

boring “does very little to guide or organize thought and works very hard to resist immediacy and prevent focus”. 4 The boring shifts the responsibility of understanding from the piece of work to the viewer, it does not dictate thought or meaning, and leaves room for uncertainty. The delayed understanding, if it ever really comes, invites the viewer to take a closer look and see things that in a new way or look at things they may have never paid much attention to before. Details emerge and things once relegated to the background of consciousness become prominent. For Opie, individual Mini-malls that are driven by without a second thought, often let alone a first, are now permitted to be scrutinized and picked apart, to find some overarching thread that ties them together, but as a collection that may never come.

“In Oklahoma City, I delivered newspapers riding along on my bicycle with my dog. I dreamed about making a model of all the houses on that route, a tiny but detailed model that I could study like an architect standing over a table and plotting the city.”Catherine Opie, Interview with the J. Paul Getty Museum

Hito Steyerl writes “The poor image transforms quality into accessibility, exhibition into value into cult value, films into clips, contemplation into distraction. The poor image tends towards abstraction; it is a visual idea in its very becoming”. 5 She argues that these copies have their own agency apart from just being low-resolution descendants from the original form and composition. “It is about its own conditions of existence; about swarm circulation, digital dispersion, fractured and flexible temporalities. It is about defiance and appropriation just as it is about conformism and exploitation”. 6 Conversely, Walter Benjamin derides reproduction and says that process of producing copies, or “forgeries”, eliminates the aura from the original. 7 Even a visually perfect reproduction lacks the original’s presence in time and space and can never

attain the same status as the original without an aura. But, this is irrelevant in the age of digital reproduction for Hiro Steryl. The degraded quality is almost like a badge of honor. It is a physical manifestation of the image’s velocity, intensity, and spread. A poor image exists because of the countless times it has been downloaded, compressed, ripped, and shared. In doing so, it detaches from the original and starts to become a new, abstracted, and independent image.

Thomas Ruff’s Jpegs series utilizes the inherent artifacts of compression to re-contextualize tranquil landscapes, scenes of war, and natural and man-made catastrophes. Like Catherine Opie’s Mini-mall series, Ruff takes images and prints them at an enormous scale. While Opie is interested in giving mundane objects a new sense of importance, Ruff does so to

exploit the underlying structure of the digital image, the pixel. The pixel becomes a “painterly stroke” when compressed and enlarged and moves the image from a low resolution copy to an entirely new image. The fuzziness introduces a new degree of uncertainty and doubt that the original high-resolution works so hard to remove. The new image allows for an entirely new experience. Like Steryl Ruff works against the fetishization of high resolution images. By exposing the pixel itself Ruff says his work is very much a manifestation of how technology changes the way we perceive the world and how we look at images. 8

8. Museum of Modern Art. “jpeg msh01. 2004 | SEEING THROUGH PHOTOGRAPHS”,Youtube, 13 April 2020 https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=cNoY-PQYEbM&feature=emb_title

--- “As an artist I should always technology and show them. Now world the structure of the photographic about the photographic grain, a stupid square it can be manipulated replace the pixel with one another old image much easier than before

Now that we live in this digital photographic image is no more but the pixel. Since a pixel is manipulated easily. So you can another and you can change an before in the analog world.” ---

Ruscha’s documentary, “deadpan” images of the Sunset Strip were important to Denise Scott Brown not for their open ended style or their openended subject matter, but for the permissive way of seeing implied by the combination.” 8

The series of photographs, Every Building on the Sunset Strip, could be seen as representation of Los Angeles itself. One that lacks a specific focal point in the expansive, omni-directional

sprawl. The mundane subject matter helped little by the style of photography to make it appear anything other than banal. 9

The ordinariness of the subject matter and amateurish style of photography strangely allow the viewer to see the subject manner in a new way. While it is meant to be similar to the way a viewer would see the buildings as if they themselves were driving down the Sunset Strip,

seeing the familiar images in a new context of a photography book may cause them to be brought into focus.

“I thought it would be really interesting to take the panorama, something that has been predominately used as a landscape camera and reiterate the architecture of Los Angeles . The ability to fit the entire mini-mall in the frame began to create a sense of an urban landscape”

Catherine Opie, Interview with the J. Paul Getty Museum

This work aims to synthesize the ideas of Atwood and Steryl by examining how Denise Scott Brown’s fragmentary, unfocused experience of Los Angeles could be represented in the digital age.

To do so, videos were taken while being driven down the Sunset Strip. No special attention was paid or care taken to capture the video in a professional manner. It was done in the same amateurish way a tourist might take a video to post to social media or akin to Ed Ruscha’s “rigorous” effort to make his photographs in Every

Building on Sunset Strip appear “generic”. It was meant to mimic the same view a passenger experiences while, according to Catherine Opie, “whizzing past” these structures. Billboards, facades, parked cars, people, and murals were captured in the same video with no attempt to differentiate between any of them or elevate their status from mundane things.

Next, individual frames were extracted and their quality degraded similar to Thomas Ruff’s Jpeg series. The new low-resolution images started

to resist the familiar immediacy of the high-resolution video frames. A level of fuzziness was introduced and the colors of the street scene became abstracted. New relationships between adjacent objects formed as their boundaries softened and became impossible to view an exact delineation between where one object ended and another started. As frames became stacked upon each other the ephemeral, fleeting images of the video can be seen directly next to each other as the dimension of time is mapped.

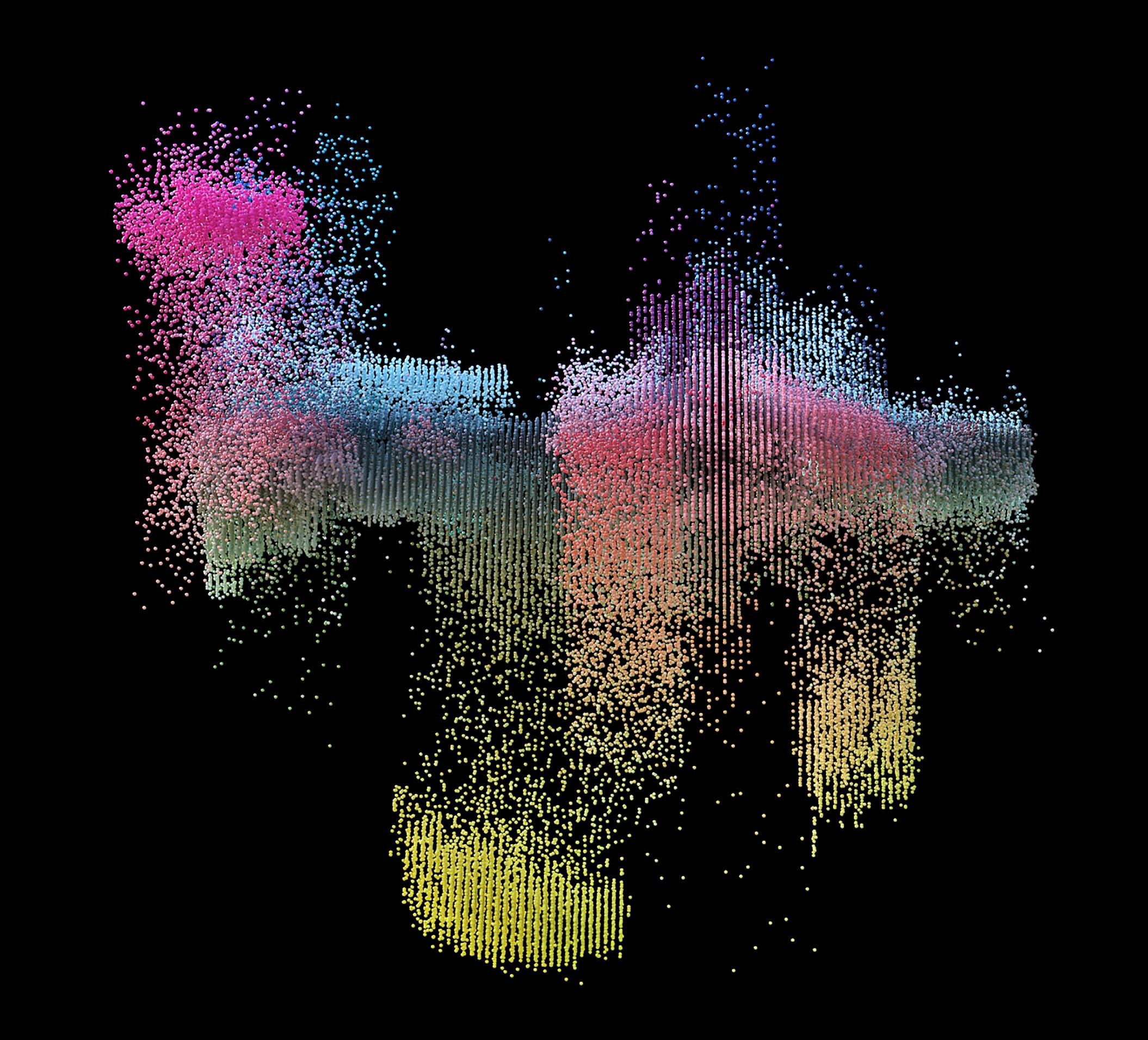

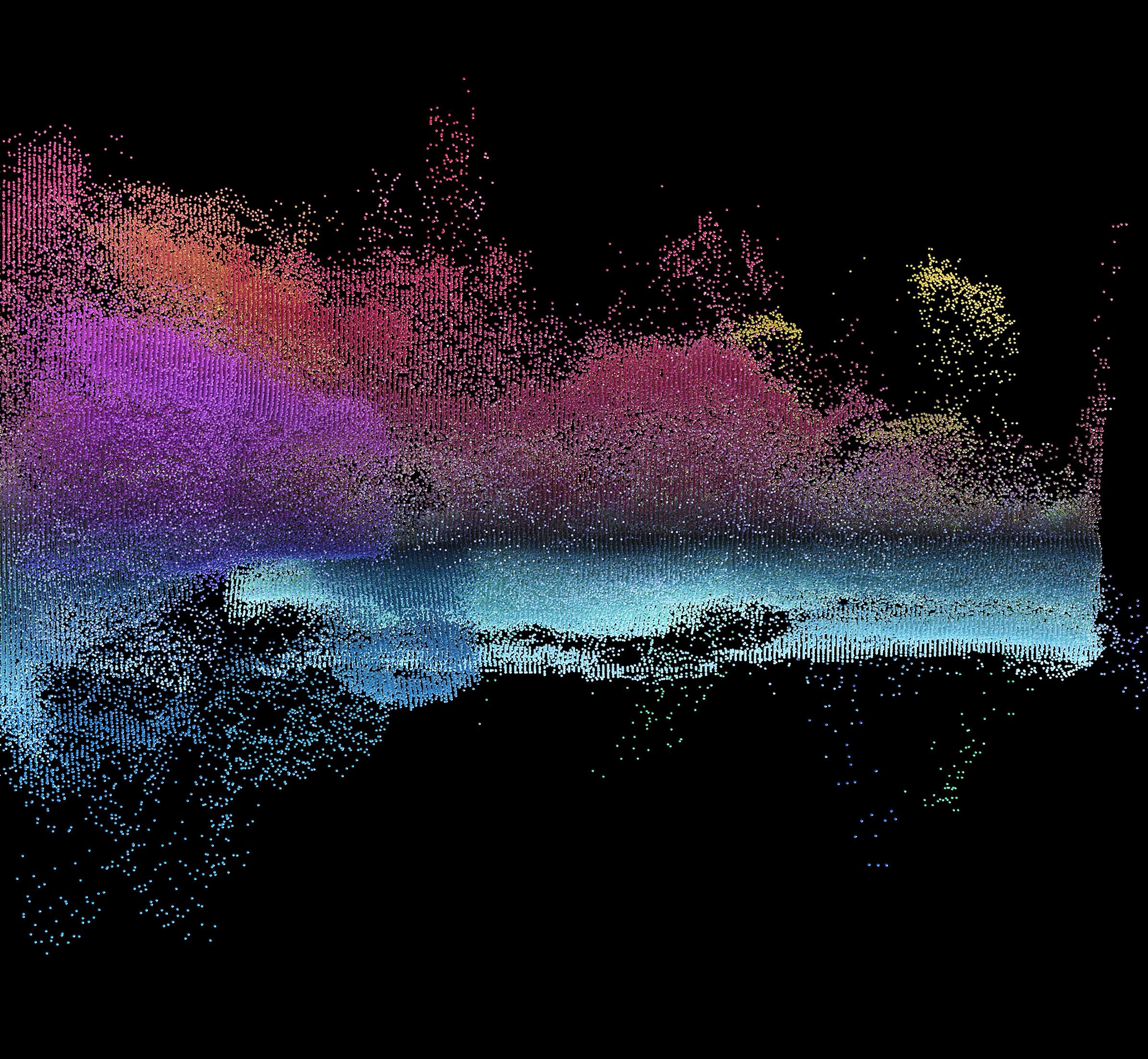

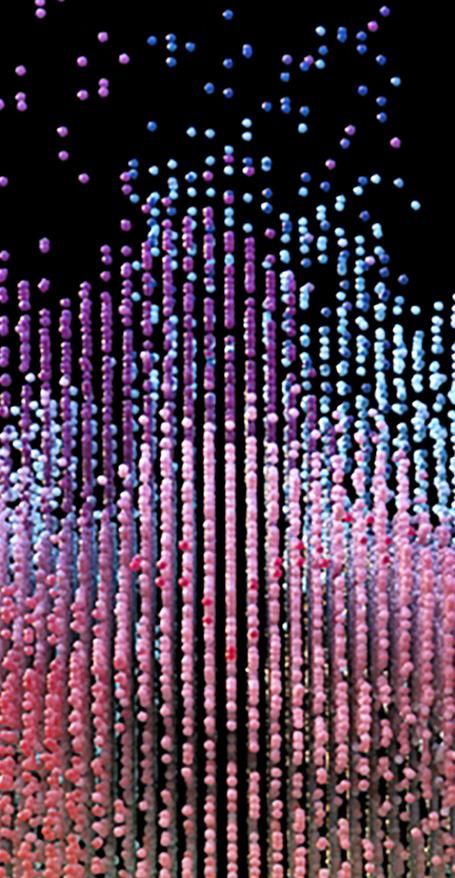

Unlike Ruff’s image, the pixels were not confined to manipulation in two-dimensional space by averaging adjacent pixel color values. Rather, each pixel in every frame was translated in three-dimensional space according to its HSV value. By doing so an entirely new image can be formed from the same underlying pixel data. By giving pixels a position in space entirely new relationships emerge. Each frame becomes a representation of the image in color space and previously flat images now have spatial qualities.

The composition of the Sunset Strip remains linear like in Ed Ruscha’s work. The disjointed and seemingly randomness of Opie’s photographs at her MOCA show is not necessary to form the same fuzziness

and fragmentary experience Scott Brown describes. The familiar billboards, facades, parked cars, people, and murals become abstracted to the point that they are no longer discrete objects. Instead they introduce undulating rhythms, splotches, and swirls of color which are impossible to pinpoint the exact provenance. While these representations of the Sunset Strip may meet some the requirements of Atwood’s “boring’, namely sharing the same open-ended, permissive, blurry, and difficulty to bring into focus they are not boring themselves. For Atwood, the boring arose when discreet, familiar objects were loosely held together by resisting the immediacy of organizing thought. Atwood’s boring requires much effort of the viewer to willfully search for the

relationships between objects. However, the abstraction of the pixels is an immediate tell that a new relationship is being made and invites the viewer to take a closer look. Here, the work of the viewer is not to understand there is a relationship between images that they must search for, but the work is to understand the new images themselves. +++

Atwood, Andrew. “Not Interesting: On the Limits of Criticism in Architecture”, Applied Research and Design Publishing, 2019.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, Schocken Books, 1969.

Museum of Modern Art. “jpeg msh01. 2004 | SEEING THROUGH PHOTOGRAPHS”,Youtube, 13 April 2020 https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=cNoY-PQYEbM&feature=emb_title Steyerl, Hito. “In Defense of the Poor Image”, e-flux journal #10, 2009, p. 8.

VS 4200

Instructed by Curime Bautliner and Andrea Cadioli with Casey Reas

Partnered with Faris Ahmed

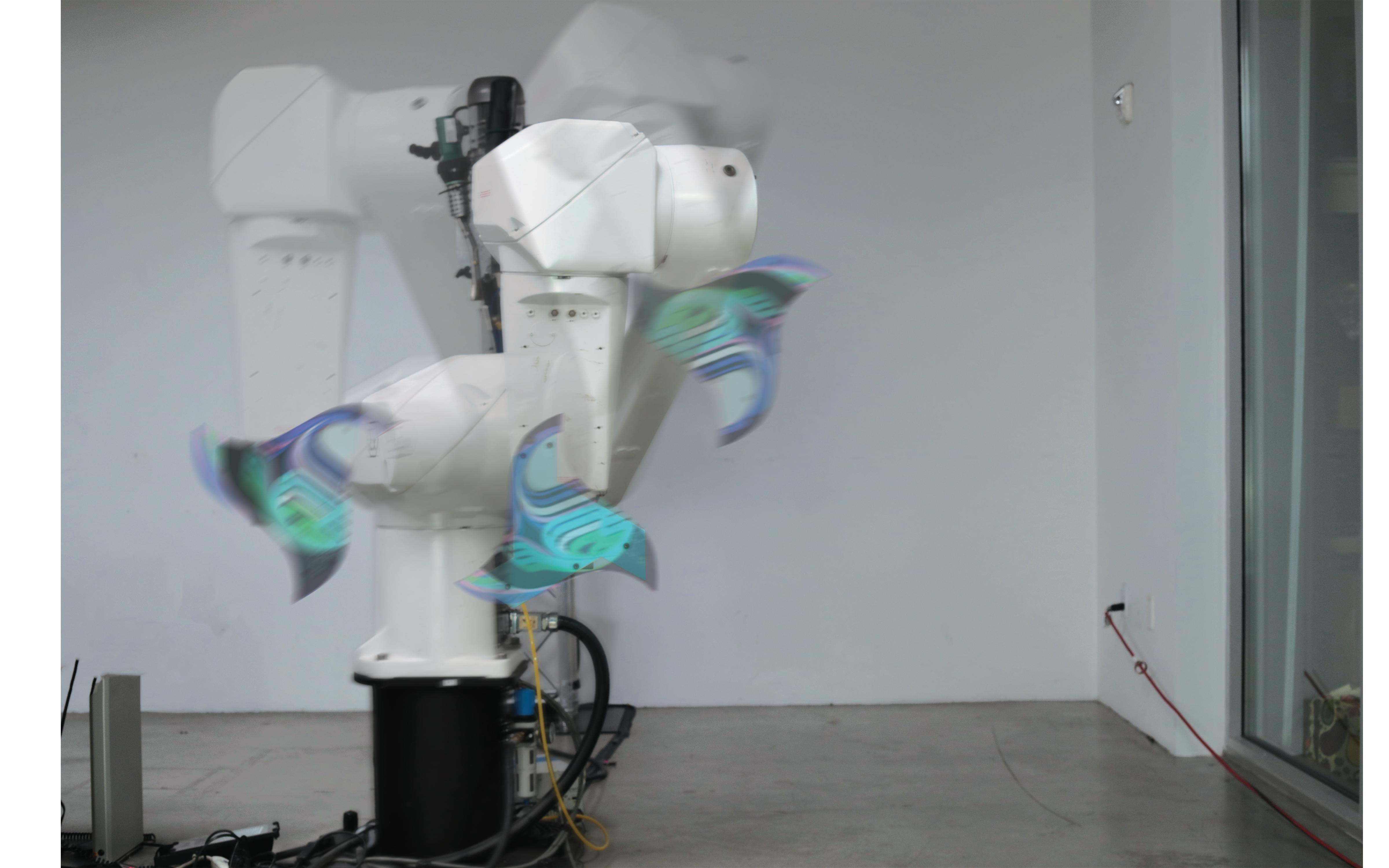

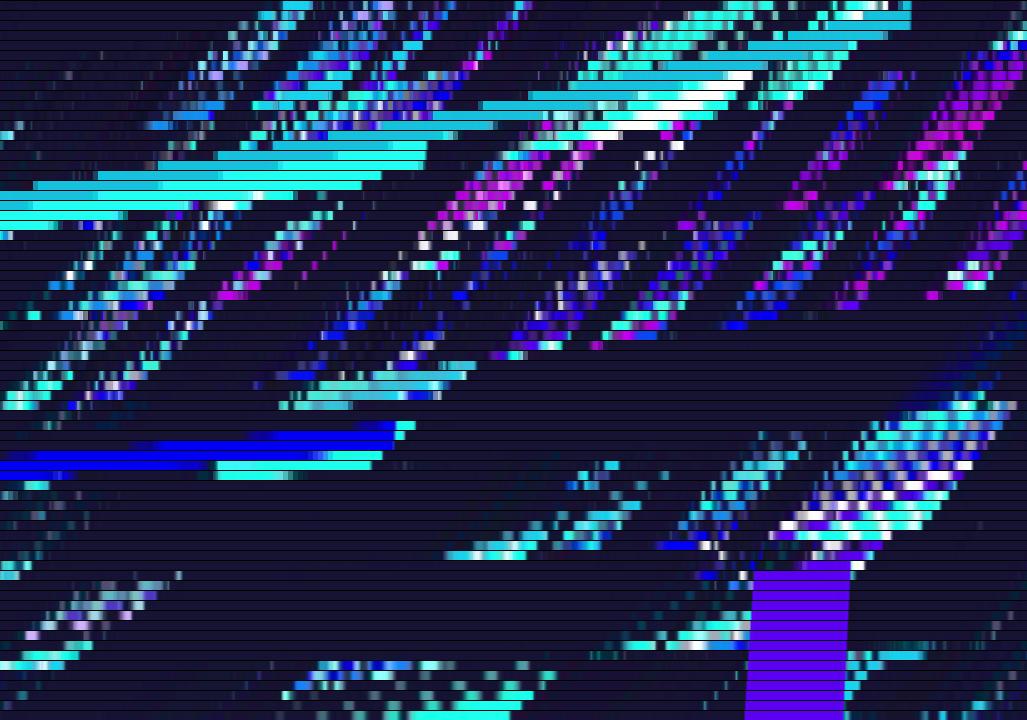

Using the space of the postdigital, 2.5D canvas this project re-examines the work of Lucio Fontana and the potential of a gestural cut. This project uses the space of an architectural facade to investigate opposing dualities like singularity/multiplicity and static/movement on a continuously evolving canvas. Parametrically generated curves are used to design evolving pattern animations that explore repetition, tiling, and overlapping. The manipulation of these curves using the tools of

color and hatches to introduce variation and unexpected moments of congruity . A single frame of the animation printed on canvas and in combination with cut and etched acrylic sheets were mounted on a frame and attached to a robotic arm . The panel is recorded as it is rotated into different positions to produce variations in light qualities and folds in the cut canvas due to the effect of gravity. A composition consisting of the panel in various orientations shows the differences produced in

a single image as the panel, like the printed image itself, fluctuates through time. The same printed frame was also digitally manipulated to create an alternative animation altered digitally as opposed to the physically manipulated canvas.

Includes excerpts from Fall 2019 VS 4200 - Visual Studies I Syllabus

“We are living in the mechanical age. Painted canvas and standing plaster figures no longer have any reason to exist. What is needed is a change both in essence and form . What is needed is the supercession of painting, sculpture, poetry, and music.”

Lucio Fontana, Excerpt from Fall 2019 VS 4200 Syllabus

“Any relationship between a building and its users is one of violence, for any use means the intrusion of a human body into a given space , the intrusion of one order into another.”

Bernard Tschumi, Excerpt from Fall 2019 VS 4200 Syllabus

Fall 2019

HT 2200 Instructedby

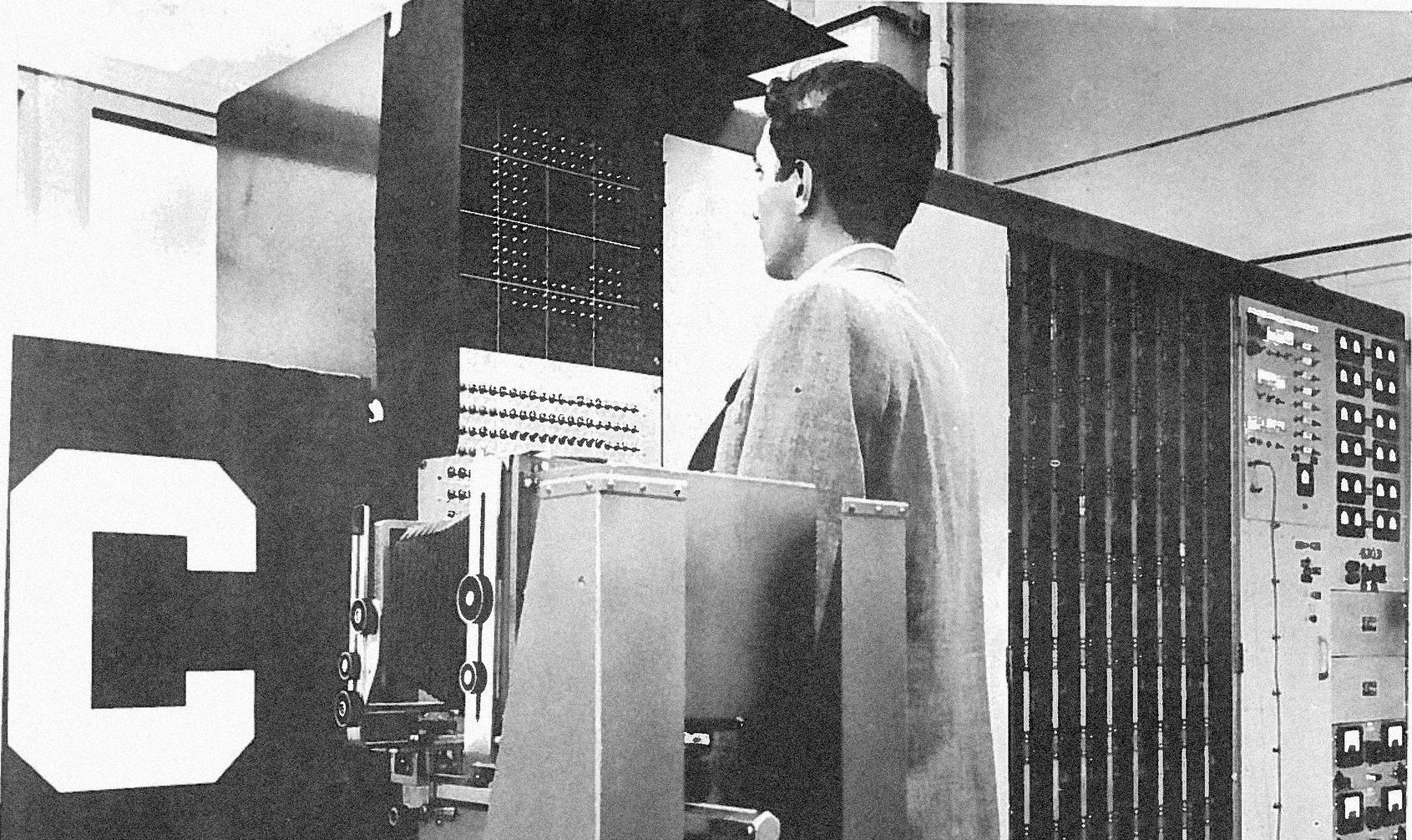

Jonh Cooper and Marcelyn GowAs with any transformative technology, the inevitable integration of machine learning into the daily life of millions of people will ultimately produce unintended cultural consequences . Although growing rapidly, there is still time to shape the implementation of this technology. In particular, it is necessary to better understand the influence that artificial intelligence will have on the relationship between culture and design . Although the algorithm, the fundamental base of artificial intelligence, has a long history

in the culture and development of society of humans, it cannot be assumed all applications of algorithms will be beneficial to society. While this use of the algorithm introduces an entirely new suite of applications such as the ability to mimic social behavior, it does present challenges to other aspects of design. New integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence must remain conscience of the changes it will have on the production of labor and the role of humans in implementing the generated

output. The careful consideration of the effects of artificial intelligence is not to dissuade the use of the technology in the future, but to help make decisions that benefit society.

The introduction of a technology that drastically alters fundamental aspects of the world in which it was not designed for is not unprecedented.

One such example, the internet, which was originally developed to provide a platform for the U.S. Department of Defense to communicate and exchange information has grown to become a key, essential element in the daily life of billions of people. With any new, disruptive technology there will be changes and consequences to implementing the technology that cannot be predicted. The development of the internet was not intended to radically change social behavior and culture. But, it did. Artificial Intelligence, or AI, is another one of these technologies that will cause a fundamental shift to the world and produce cultural changes it was not intended to. While it is still in a somewhat nascent stage, it is important to understand some of the consequences this technology may have in order to develop solutions and shape the technology in productive ways. In particular, it is necessary to

better understand the influence that artificial intelligence will have on the relationship between culture and design and what some of the consequences of becoming more dependent on this technology will be.

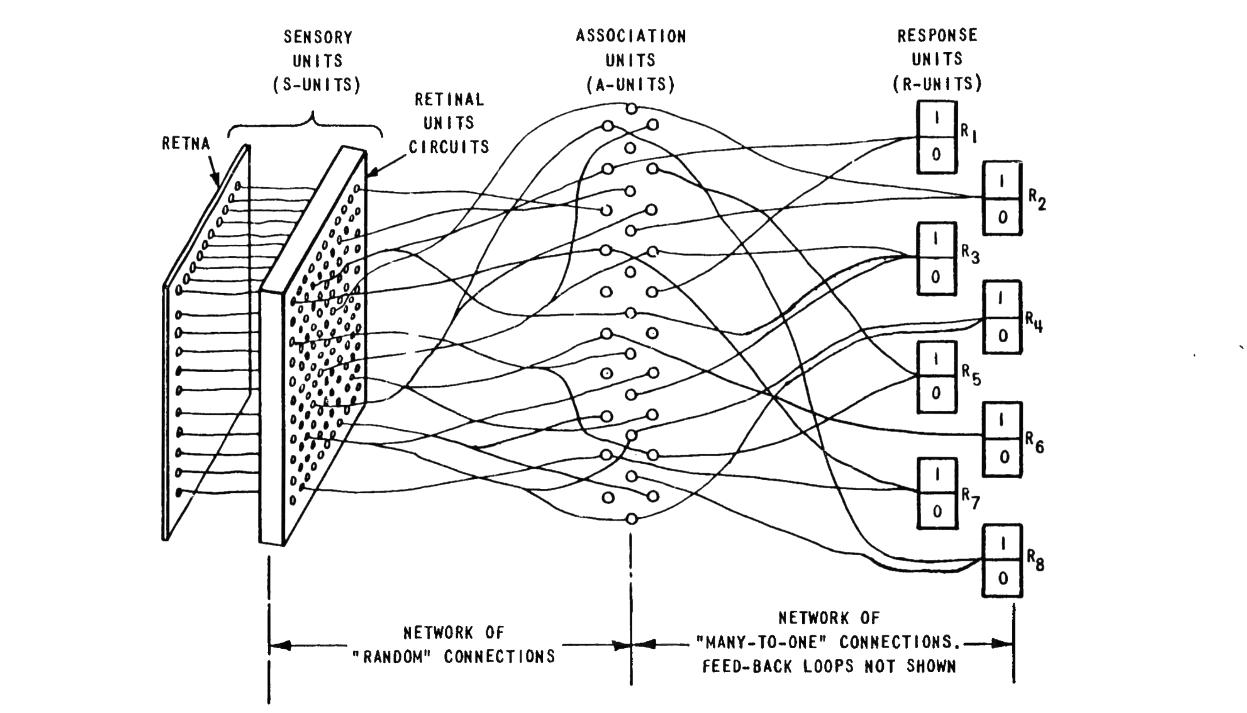

To better understand possible consequences of artificial intelligence on humans in the future, it is necessary to investigate the historical relationship between the foundation of artificial intelligence, algorithms, and humans today. Matteo Pasquinelli, in his recent e-flux article, Three Thousand Years of Algorithmic Rituals: The Emergence of AI from the Computation of Space, argues that algorithms have long been an important, and, at times, necessary component of human social behavior and even for the development of society at large. Using the example of an Agnicayana ritual, in which a fire altar is constructed by

the placing of thousands of bricks in a precise manner to create a falcon, he dismisses the common misconception that algorithms are a modern mathematical phenomena that arose alongside the computer in the second half of the 20th century. 1 More so, algorithms have not been limited to solely the fields of mathematics and mechanical computation. The French mathematician, JeanLuc Chabert, notes that “the Babylonians used them for deciding points of law, Latin teachers used them to get their grammar right, and they have been used in all cultures for predicting the future, for deciding medical treatment, or for preparing food”. 2

It is important to note that Pasquinelli states algorithms are not just the solution to an economic or social need, but they play a pivotal role in the emergence of culture itself. Pasquinelli continues and says the “primitive abstract machines” of social segmentation and terrorization that make human culture emerge could be recorded through a census and logical forms could be made from social ones. 3 Here more abstract human behavior and conditions are able to be collected and analyzed to produce a more concrete representation of a population that cannot be determined through visual perception and interpretation.

Clearly, the encoding of social human behavior into an algorithm that can be broken

down into discrete parts is not something novel. But this behavioral information gathered had a more limited scope on daily life in the past than it does today. Information was slow to be processed and often exchanged through rituals and spoken word. With the advent of today’s complex technological system that has become ubiquitous in the daily life of many, especially in the west, the relationship between humans and algorithms has changed. The explosion of mechanical computation, real-time analysis, and the generation of enormous sums of personal behavioral data has altered the relationship so much it has given rise to the previously stated misconception that algorithms are a recent invention. Today, the “algorithm” and “computer” are almost synonymous. This has produced

a new culture of the early 21st century in which the goal of technology is to produce a symbiotic relationship between humans and data to create a more personalized and efficient system.

Pasquinelli argues that society has now taken a “topological tun” in which we have passed from a paradigm built on passive information to that of an active one. 4 This active paradigm is what people now refer to as AI. A key difference from the previous, passive paradigm is the power dynamics between the humans and algorithm. Previously, the algorithm was a direct processing of external variables which output data that forms a new relationship or connection between the input,

be it a census, recipe, or ritual. While the algorithm was capable of doing tasks more efficiently and quickly than humans, it still served a subservient role. It was only able to process what it was given and had no agency of its own. However, this dynamic between human and algorithm or human and machine has changed in the recent, active paradigm of the 21st century. The development of artificial neural networks has led to the ability of computers to not only learn human social behaviors, but to imitate them to the point where the difference between human and machine is indeterminable. The ability for humans to form complex social behaviors and culture has previously been a clear demarcation between not only human and machine but humans and other species. The capacity of algorithms to successfully imitate and perform these behaviors without a direct control from humans blurs the previously clear hierarchy.

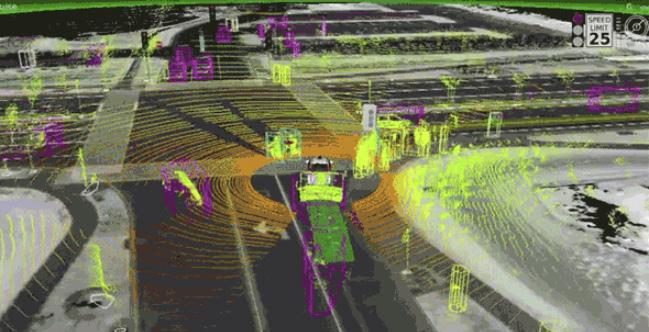

To illustrate the difference, Pasquinelli gives the example of self-driving cars. He says that “driving remains an essentially a social activity, which follows codified rules (with legal restraints) and spontaneous ones, including a tacit “cultural code” that any driver must subscribe to. Driving in Mumbaiit has been said many times- is not the same as driving in Oslo”. 5 The active paradigm allows for the computer operating the self-driving car to make decisions in situations in which it is not explicitly programmed what to do. The machine begins the gain some form of self-determinacy and an

agency of its own. The erosion of the top down approach in which computers are wholly subjected to pre-scripted human encoded language to one in which machines make decisions from learning on their own opens up an almost infinite amount of new applications. AI that is capable of learning social rules in a constructed space, like a road in the case of self-driving cars, would be enormously impactful on architecture which can be seen as the manipulation of a constructed space to shape or facilitate human social behavior.

The rapid expansion of computer power and its ever-growing role in culture has led some to question if it is possible the impact of AI is changing culture too quickly. Bruce Wexler, a professor of psychiatry at Yale University, suggest this may happen in the future given current trends. In his article, About Tomorrow, he writes that “humans are the only animal that shape and reshape the environment that shape our brain. This powerful combination is the basis of cultural evolution, and most features of the human minds, behavior and communities”. 6 The radical technology of one generation is seen as commonplace in the next which makes it possible for society and culture to adapt to these changes. The problem, according to Wexler, is not the adoption of AI itself, but the rate at which AI will change society. He asks if “there is something such as ‘too much too fast’- will the ship fall apart if the speed is too great? Where is the danger? At the level of the individual’s

ability to adapt? The ability of social structures to function at such high speeds? Or in an alteration in the type of person able to survive and succeed?”. 7 AI’s ability to learn by itself and produce results unattainable to humans may require humans to relinquish control. It may be that a society that freely accepts the results of the AI as one that can adapt quickly and one that resists will be left behind technologically and socially. By yielding to computers, humans will exchange local culture and customs to one that is centered on efficacy and data. One hypothesis is that because the goal of AI is to learn quicker and perform better the more access it has to data, it would eventually which create a positive feedback loop that becomes untenable to refute.

The onslaught of new information may make it easier for people to blindly accept the results rather than going through the labor of analyzing them. In this scenario, a global culture may emerge. Wexler says “technology not only facilitates access to humanmade programming, but rather programs us as well. What difference will it make if our rearing environment becomes more centralized and more mechanical”. 4 On one hand a more centralized environment connects people who would otherwise not be able to exchange information, but at the expense of cultural variability. The homogeneous culture that emerges may reduce the number of “inputs” the machine can learn from. This

may lead to a convergence of ideas, aesthetics, and outcomes and finally a realization of the Modernist dream of an international architecture that is a product of technology and optimization can emerge.

However, recent examples show this is not always the case. The use of software already influences the design of buildings by creating tools that give preference to certain forms by making them easier to obtain than others. For example, the introduction of technology like computer-aided design drastically changed the language of architecture. It can be argued that this new technology actually produced the opposite effect and increased the variability seen in architecture and lead to new forms previously not possible under a more laborious hand production paradigm. While the introduction of software does, in some cases,

create a specific design aesthetic, like parametricism, the introduction of computer-aided design has increased variability. The difference, however, is that AI, as previously stated, is not a passive system like parametricism. Parametrcism is still controlled by humans and, with that, all the differences that arise from the variability inherent to human decision making. The localized culture and societal influences are still able to affect the end result. While humans will influence the software that comprises the AI, the variability introduced by people will take a reduced role to the software itself. This shows the need for AI and neural networks to be considerate of culture and variability. Like the software used in self-driving cars, the AI in the design field must work to learn the social and cultural habits of people and integrate it into their learning. Without these inputs all that is left is

the optimization of data which lacks any fingerprint of human variability and differences that produce growth and new ideas.

Another aspect of the introduction of AI to the social behavior of humans is the ways in which it will redefine our relationship with the production of labor. Historically, the relationship between humans and labor has not been static and largely a function of the availability and implementation of technology. The tools created by technology are used to expedite labor, make it less strenuous, and more efficient. However, for most of human history this relationship between human labor and technology was very distinct. The technology was under full control of the human and its existence owed entirely to help achieve a task with the greatest efficacy. This changed with the Industrial Revolution.

“When architecture becomes robotic, its design process must extend beyond schematics , design development, and construction, and into the lifespan of the building, becoming a learning process in the context of its environment.”

The transition from hand production methods to the development of machine tools and the mechanized factory system ushered in machines that could break down tasks into discrete parts and employ unskilled laborers on massive scales that radically shifted the socioeconomic landscape. Here, the relationship begins to deviate from the historical norm. The human’s ability is greatly increased by relinquishing power to the machine.

Axel Killian, in Autonomous Architectural Robots writes “we build robots in the image of ourselves, but think of them more as objects that manipulate other objects. In a utopian scenario, these anthropomorphic robots take over strenuous, inhuman labor to free humans for higher tasks and leisure, whereas in a dystopian one, they become a treat to humans, taking away their livelihood,

outpacing and outdoing them, step by step, in every area of human ability and labor, both physical and mental”. 9 The more likely scenario is that the future will fall somewhere in between the extremes posited by Killian. It then becomes a question of what jobs are left to the humans in a world that is being increasingly automated to smarter and more efficient machines. In respect to design, Killian seems to have believed the future will fall closer to the utopian pole. He states that. 10 Interestingly, it seems he sees humans taking a larger role in the design of a building, the more the process becomes automated and focusing on higher level tasks than architects currently design for. But, in an extreme utopian or dystopian scenario like Killian outlines, it seems unlikely humans will be involved in planning how the building will function autonomously in the future and

9. Kilian, Axel. “Autonomous Architectural Robots.” e-Flux, no. 101, June 2019, pp.1.

instead be relegated to design a space where the AI can operate independently. If the AI is truly able to learn and mimic human behavior and optimize the results any human intervention would be detrimental to its efficiency once the AI becomes autonomous and can learn on its own. A small population of humans would be responsible for the design and implementation of the AI and the rest of the humans would simply act as a vehicle to perform menial tasks. Killian sees AI and autonomy as a tool used like pre-industrial humans rather than AI becoming the equivalent of a mechanized factory system. It is more likely humans continue to cede power to the machine and algorithm. What then becomes the end result of the algorithm and how do humans choose to implement the solution that has been generated by the AI? One possible scenario is a future that

continues to cede power to the machine and algorithm.

What then becomes the end result of the algorithm and how do humans choose to implement the solution that has been generated by the AI? One possible scenario is a future that is less focused on an initial design and instead becomes concerned with choosing from the output results generated. This curatorial act is already happening in the post-digital world of architecture. Michael Meredith, in his essay titled One Thing Led to Another, warns of the dangers by describing curating on the internet as “being based on analogy

and a unifying resonance. It collects wholes and celebrates their coexistence. If you like this, you will also like this…images maintain their identity and integrity within a collection, a universe made out of tiny planets, producing a simultaneity where discrete elements are flattened out. 11 The danger being that AI and neural networks will learn what a person or society likes and simply filter out what it perceives we don’t want to see. A person’s behavior will train the system to curate an ever-decreasing variability of outcomes. This behavior will not produce a topdown homogeneous design, but instead create different clusters

that operate independently of one another and pass each other like ships in the night. This is currently happening on social media sites like Twitter and Facebook in which the news and realities of the outside world are filtered by algorithms to reinforce a preconceived held belief in order to keep a person engaged and visiting the website. People do not like to be challenged but instead have their beliefs reaffirmed. For AI to be successful in design it needs to learn not only what we like, but to introduce tensions and challenge curatorial homogenization.

The ability to recognize potential changes to design and architecture that result from altering the relationship between machine and the human is important to avoid unintended consequences. Although the algorithm, the fundamental base of artificial intelligence, has a long history in the culture and development of society of humans, it cannot be assumed all applications of algorithms will be beneficial to society. The change to an active

paradigm application of the algorithm inherently shifts the relationship between the user and machine to one that is no longer as clearly hierarchically defined. While this use of the algorithm introduces an entirely new suite of applications like the ability to mimic social behavior it does present challenges to other aspects of design. New integration of AI must remain conscience of the pace the technology is introduced and the changes it will have on the

production of labor and the role of humans in implementing the generated output. The careful consideration of the effects of artificial intelligence is not to dissuade the use of the technology in the future, but to help make decisions that benefit society.

+++

Chabert, Jean-Luc. “Introduction.” A History of Algorithms: From the Pebble to the Microchip, Springer Verlag, 1999, p. 1.

Kilian, Axel. “Autonomous Architectural Robots.” e-Flux, no. 101, June 2019, pp. 1–5., doi:10/18/2019.

Meredith, Michael, and Ana Miljacki. “One Thing Leads to Another.” UNDER THE INFLUENCE: A Symposium, ACTAR, 2019, pp. 67–72.

Pasquinelli, Matteo. “Three Thousand Years of Algorithmic Rituals: The Emergence of AI from the Computational Space.” e-Flux, no. 101, June 2019, pp. 1-12., doi:11/18/2019

Wexler, Bruce. “About Tomorrow.” e-Flux, no. 101, June 2019, pp. 1–5., doi:10/15/2019