5 minute read

Inventor of the Christmas card

Sarah Brydges-Willyams Politicians and Primroses

In 1863 a childless Torquay widow died and left her house and much of her estate to an aspiring politician who was on the verge of bankruptcy. at kindness changed Britain and the world. Kevin Dixon tells us more.

Advertisement

Benjamin Disraeli

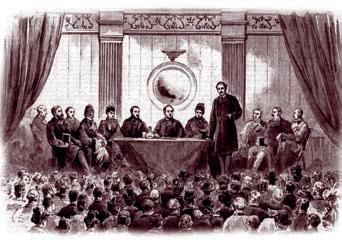

An early meeting of the Primrose League

Mount Braddon

Mount Braddon is an imposing Grade II villa just above Torquay harbour. It was built in 1827 for Sarah Brydges-Willyams, the wealthy widow of a colonel in the Cornish militia. Sarah was born Sarah Mendez da Costa and was of Spanish-Jewish descent; she believed that she might be related to the famous politician Benjamin Disraeli who had Italian-Sephardic Jewish ancestry. She then began writing to him.

Initially Disraeli regarded Sarah as an elderly eccentric and even sought legal advice. However, when one of the letters included a donation of £1,000, he agreed to a meeting. is led to a long-term friendship between Disraeli, his wife Anne and the childless widow. e Disraelis then visited Torquay every year and corresponded with the owner in between – about 250 letters survive.

When Sarah died in 1863, she was buried at Disraeli’s home Hughenden Manor in High Wycombe. In recognition of his e orts to further the cause of Zionism, Sarah had bequeathed Disraeli £30,000, three quarters of her estate and Mount Braddon. is bequest probably saved him from bankruptcy as he had debts resulting from his lavish lifestyle and poor investments. However, he never wanted to move to Torquay and sold Mount Braddon for £1,850.

e story goes that Disraeli’s favourite ower was the primrose and that he greatly admired and was inspired by those growing at Mount Braddon. Recognising this enthusiasm, Queen Victoria frequently sent him bunches of primroses; he wrote back that the primrose was, “the ambassador of spring”. When the twiceelected Conservative Prime Minister died in April 1881 it caused widespread popular grief and Victoria sent a wreath of primroses to his funeral. On the anniversaries of his death the ower came to be worn by Conservative Party members.

In the 1880 election, the Conservatives lost badly to Gladstone’s Liberals and the Tories recognised that they needed to reach out to new voters. And so in 1883, Lord Randolph Churchill and John Gorst launched a new mass movement to promote the spread of Conservative principles. As Disraeli had been the hero of Popular Conservatism and had done so much to expand the franchise to working class men in the cities, the movement was named the Primrose League in his honour. e Primrose League had more support than the trades’ union movement and in 1910, when the entire national electorate was only 7.7 million, it had a membership of almost two million. Dedicated to spreading Conservative principles, it transformed how

political parties worked, and ensured the domination of the Conservative Party at the end of the nineteenth century. Its in uence is still felt today. e strength of the League was due to its cross-class appeal. Notably, the League didn’t seem that interested in political theory – only “atheists and enemies of the British Empire” were excluded – and the motto was ‘Imperium et libertas’ (Empire and liberty). ough the League’s beliefs were vague, it nevertheless galvanised political participation and provided a more social aspect to campaigning and lobbying. It began an extensive network of social activities with sashes and enamel badges being worn at music hall dances, high teas, excursions by train, cycling clubs, summer fetes – such as those at Cockington – and many other activities. Magic lantern shows with slides of scenes from the Empire were particularly popular. Hence, the long-studied phenomenon of working-class Toryism.

It also o ered a training ground for aspiring politicians – Winston Churchill, aged 22, made his rst public speech to a Primrose League rally on July 26, 1897. e League speci cally appealed to women at a time before they were able to vote – by 1891 over half of the membership of the League was female. Indeed, many women rst experienced political participation through the Primrose League and would go on to in uence the various women’s su rage groups striving for support in the decades before World War One. is may have been

greatly signi cant; when women over 28 were granted the vote in 1918, despite expectations to the contrary, women proved to be far more likely to back the Conservatives than either the Liberals or the new Labour Party. e campaigning of the Primrose League, alongside Liberal divisions over Ireland, helped the Conservatives maintain their grip on power through the latter years of the nineteenth century.

But with the granting of universal su rage after the Great War, the Conservative Party leadership decided that, “a mass membership was necessary if the Conservatives were to be on an equal footing with the mass battalions of the trade unions”. is led to an increased party membership, and the need for ancillary support organisations such as the Primrose League diminished. Also, women had now gained the vote and could be full members of the Conservative Party.

After 121 years, the Primrose League was nally wound up in 2004 and its remaining assets were transferred to the Conservative Party.

Now the huge success of the Primrose League is largely forgotten, as is Sarah’s gift to Disraeli, which ensured that one of our greatest politicians could remain in Parliament. In 1845 Disraeli in ‘Sybil, or e Two Nations’ developed the idea of One Nation Conservatism. In 2010 Boris Johnson explained his political philosophy: “I’m a onenation Tory”.

The vault of St Michael and All Angels Church, Hughenden, containing Benjamin Disraeli, his wife Mary-Anne, and Sarah Brydges-Willyams whose epitaph is on the left of the three.