4 minute read

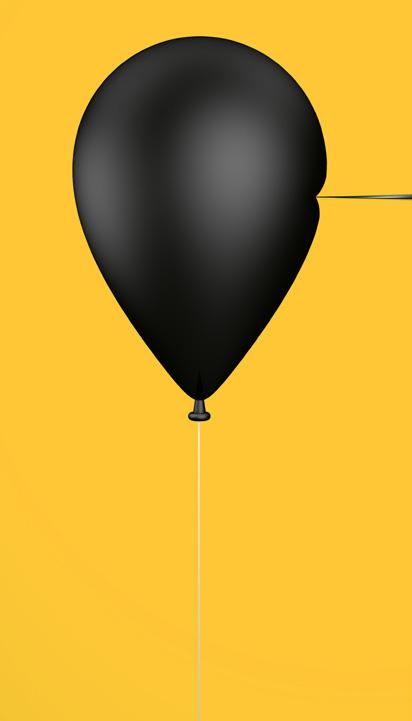

Mr Bond Lives Again

The spectre of the death of the bond is receding, writes Mark Riggall, portfolio manager at Milford Asset Management. And he suggests perhaps there’s a case for owning bonds again.

Late last year I wrote an article about the dire outlook for bonds. It was called “So, you expect me to perform? No, Mr Bond, I expect you to die”. Declining bond returns were expected to have an impact on the performance of diversified funds that hold bonds, including KiwiSaver. They did. Since then, bonds have been terrible performers. Shares have also seen some volatility this year, but global investor appetite for shares appears to be relatively undimmed, with evidence of significant buying from global retail investors this year.

Advertisement

Is it time to switch?

Can we make a case for owning bonds and is it shares’ turn to kick the bucket?

Since July last year, the S&P New Zealand government bond indexhas fallen by around 9 per cent to the end of March 2022. That compares to New Zealand shares, which have fallen by 4 per cent over the same period and global shares which are up 2 per cent over the same period. Unfortunately, bond-heavy Conservative funds have borne the brunt of this, largely underperforming Growth funds on a oneyear basis to end of March, despite the falls in share markets this year. So, bonds have been a terrible investment recently, but should investors still steer clear?

Yields look more attractive

The falls in bond prices mean yields going forward are now much more attractive. The yield on a five-year New Zealand government bond was around 3.3 per cent at the start of April. Yields on offer haven’t been this high since early 2015. Yields on five-year high-grade corporate bonds in New Zealand are around 4.5 per cent. These returns aren’t that attractive versus inflation running at 5.9 per cent, but at least now there’s a reasonable alternative to holding cash. The prospects of future returns are looking better, given these more attractive yields, but what about the risk bond prices might fall further as even-higher interest rates are priced in? In New Zealand, the Reserve Bank is expected to hike rates to over 3 per cent by the end of 2022.

In the US, interest rates are expected to rise to 2.5 per cent at the end of 2022. With global inflation high and still surging, such expectations of rate hikes are understandable.

But given the large amount of hiking already priced in, and significant uncertainty about inflation and growth outcomes on the other side, it’s reasonable to assume that we’ve already seen much of

the weakness in shorter-dated bonds. What’s more, if we see economic weakness later this year, chances are these bonds could perform well as investors rein back their expectations for rate hikes.

What about shares?

How about shares: do their inflationbusting properties mean they continue to be the asset class of choice?

In theory, company revenues should rise along with inflation. After all, it is the companies that are setting the selling prices. However, input costs (including labour) are also going up. If consumer demand falls as a result of high inflation, then company margins could be squeezed and profits could stagnate. The starting point of valuations also matter for long-term returns. In times of uncertainty, like now, investors demand higher future returns and therefore lower valuations.

Global share markets are trading at a price of 17 times next year’s expected profits at the start of April, which is slightly higher than the 10-year average of 16 times. While that’s only modestly expensive, it masks a huge divergence in valuations across different types of shares. • High-growth companies have attracted a lot of attention (and investment) in recent years. This leaves them looking very expensive compared to both history and the broader market.

• Conversely, ‘value’ type companies are looking inexpensive. This segment includes less exciting businesses such as banks and energy companies, and some of these companies have valuations that are downright cheap. In the background we can see surging inflation, rapidly rising interest rates and squeezed consumer budgets. An optimist would hope for a settling of inflation and growth at more modest levels in the next few months, requiring fewer interest rate hikes than currently expected. A more cautious investor would be concerned about stagflation – persistently high inflation but stagnant demand. Whichever way the path goes, the outlook for investors is not necessarily poor. Some bonds are looking like solid investments for the first time in years. Meanwhile, share markets are still full of sensibly priced companies with reasonable outlooks. You just might have to look beyond what has done well over recent years.